22

‘I AM AN ALMOST PERFECT WAGNERIAN’

The Giuseppe Verdi who left Sant’Agata to supervise rehearsals in Milan at the beginning of 1869 for the new production of La forza del destino was living up to his reputation as ‘The Bear of Busseto’. Within the walls of Sant’Agata, Giuseppina was in despair over her husband’s behaviour.

She wrote to a friend that he had flown into a rage over a window left open. Even worse, he had lapsed into a prolonged period of absolute silence. He would not talk to her. He did not respond to her questions, or if he did so, it was with a single unhelpful word.

Husband and wife were not communicating when Verdi left for Milan, though from there he wrote to her, inviting her to come and attend rehearsals. Clearly Giuseppina was unimpressed. The fact that he had not taken her in the first place had wounded her more deeply than it might otherwise have, had relations between them not deteriorated so badly.

She wrote him a lengthy reply, which is nothing less than a cri de coeur:

I have thought carefully and I shall not come to Milan. So I will save you from having to come secretly to the station at night to slip me out like a bundle of contraband goods. I have reflected on your profound silence … and my inner feelings advise me to turn down the offer you make me … I feel everything is forced in this invitation, and I think it is a wise decision to leave you in peace and stay where I am. While I am not enjoying myself, I am at least not exposing myself to further, useless, bitter remarks; and you, on the other hand, will have complete freedom … So please let my embittered heart find dignity in saying ‘no’; and may God forgive you for the excruciating, humiliating wound that you have given me.93

They hardly sound like the words of a wife at ease with her husband. Giuseppina clearly felt herself deeply wronged. She must have known the effect her words would have on her husband, already prone to stress-related illness and hard at work supervising rehearsals of the new production of his opera. But she does not spare him.

What might have put Verdi into what seems to have been a deep depression, or at the very least the blackest of moods? It is not enough to point to an artistic temperament. The previous two years had brought much trauma into his life. The year 1867, two years before that letter was written, was an annus horribilis for him.

On 14 January 1867 Carlo Verdi died at the age of eighty-two. Verdi was in Paris. Relations between father and son had never been fully restored. The death of Verdi’s mother sixteen years earlier had done nothing to bring them closer.

Carlo Verdi had suffered from kidney problems and heart disease for some time, and Verdi must have known the end could not be far away. Yet he was not there when his father died, in the same palazzo in the centre of Busseto where the composer had once lived with Giuseppina.

Carlo’s death affected Verdi greatly. Giuseppina described him as being ‘deeply grieved’, as she was herself, although she adds that this was ‘despite the fact that we had lived with him hardly at all and were at opposite poles in our way of thinking’.94

Verdi himself poured out his emotions in a letter to a friend:

Oh certainly certainly I would have wanted to close that old man’s eyes, and it would have been a comfort for him and for me! Now I cannot wait to get home.

Verdi was not with either of his parents when they died, and he easily could have been. Did that result in a measure of guilt? We cannot know for certain, but he must have mulled over in his mind the years of estrangement, and whether they were really necessary. On the other hand, Carlo’s death might have given him a certain sense of liberation; there could be no further causes of tension, and resultant guilt, between them. At fifty-three, perhaps he was finally free of the past.

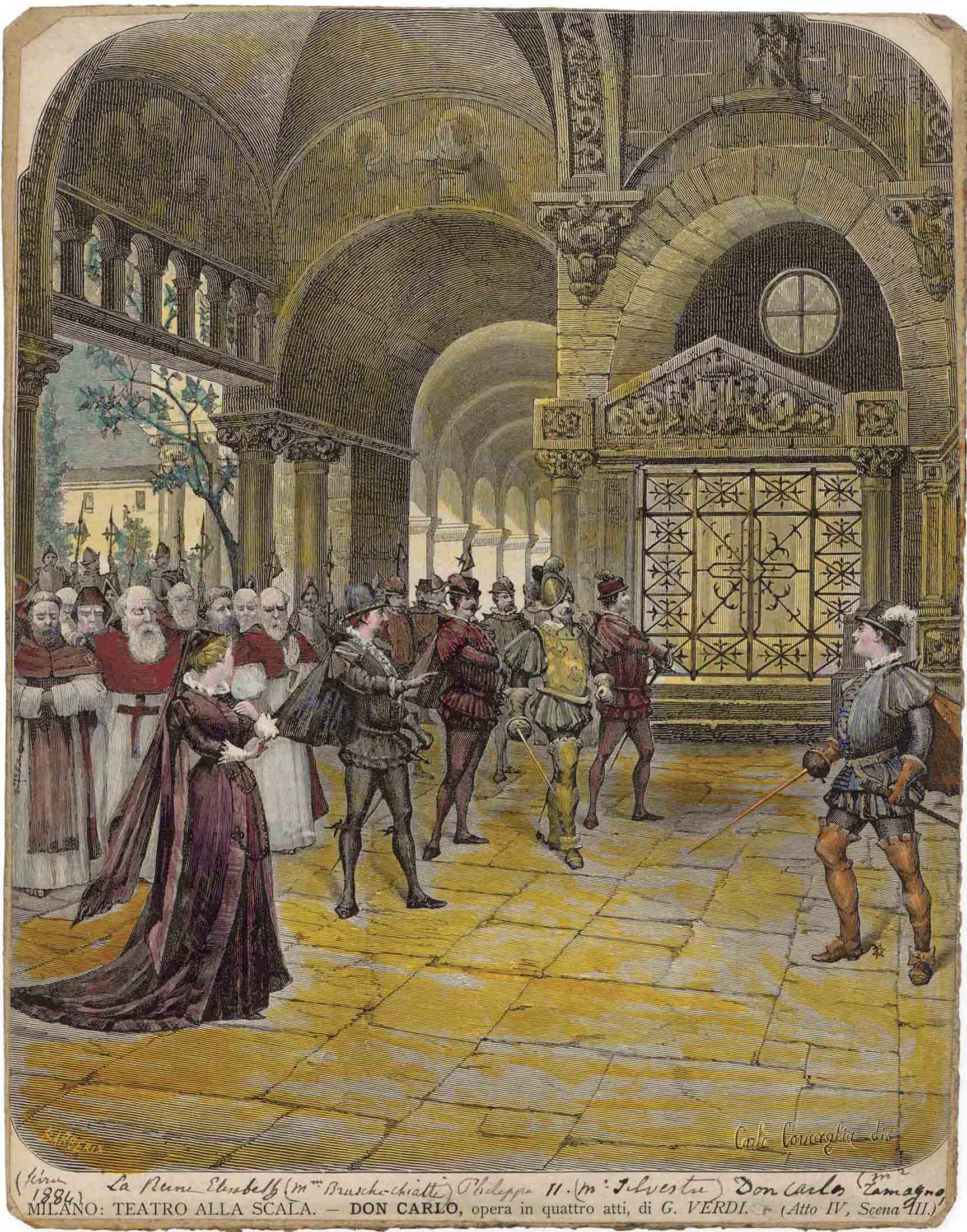

Certainly his reason for being in Paris was a strong enough one. Contracted by the Paris Opéra to produce a new opera, he had set Schiller’s drama Don Carlos, which revolved around the sixteenth-century Spanish King Philip II and his son, for whom the play is named.

The compositional process – as always with Verdi – had been difficult, even tortuous. His librettist, Joseph Méry, died having completed roughly half of the text, and a new librettist Camille du Locle stepped in to complete it.

Paris, of all European opera houses, had a penchant for grand opera. Productions of four hours’ duration were quite common. But Verdi exceeded even that. He produced a work so monumental that even during rehearsals he was cutting whole sections.

His father’s death could not have come at a more inopportune time. The opening night of Don Carlos, set originally for 22 February, was put back to 11 March, less than two months after his father’s death. He could not leave Paris and thus had to rely on others to make arrangements for the funeral and burial.

To universal consternation he stopped attending rehearsals for the new opera and refused to see anyone. The omens were not good. By the time he had recovered enough to resume work, his mood was difficult and unhelpful.

Don Carlos opened on schedule, and its reception was lukewarm at best. For once Verdi’s innate pessimism was largely justified:

Last night Don Carlos. It was not a success! I don’t know what will happen in the future, and I wouldn’t be surprised if things changed … At the Opéra you do eight months of rehearsals and end up with an execution that is bloodless and cold.95

That last sentence could have been written today. Verdi knew better than most that a truly completed opera was a rare thing. In fact the sentence before that was accurate too. Verdi began full-scale revisions almost immediately.

By the time the opera appeared in Italy under the title Don Carlo (which it retains today, rather than Don Carlos), it had undergone several changes. Verdi made more alterations five or so years later, and again nearly twenty years later. The version that finally entered the repertory was largely an amalgamation of different versions. As one musicologist put it, ‘Don Carlo seems destined to be an opera “in progress”.’96

Don Carlo would ultimately become a firm fixture in the repertory, and is regarded to this day as one of Verdi’s finest works. In it he focuses on deep issues: the conflict between an individual’s public duty and his human passions, and the need sometimes to sacrifice what is dearest to preserve honour. All the individual characters are somehow tied to each other, so that none is left unaffected by another’s actions.

The music, too, is Verdi at his best. Don Carlo contains some of the greatest dramatic music he had written to date, with a magnificent series of confrontational duets. It was undoubtedly the music that led some critics to make comparisons with which Verdi was not best pleased.

I have read in Ricordi’s Gazetta an account of what the leading French papers say of Don Carlos. In short, I am an almost perfect Wagnerian. But if the critics had only paid a little more attention they would have seen that there are the same aims in the trio in Ernani, in the sleep-walking scene in Macbeth, and in other pieces. But the question is not whether the music of Don Carlos belongs to a system, but whether it is good or bad. That question is clear and simple and, above all, legitimate.97

It was not the last time a comparison with Wagner would be made, nor the last time Verdi would react angrily to it.

The depression that settled on Verdi after his father’s death would not leave him. The relative failure of Don Carlos in Paris, or at least the realisation that much more work on it was needed, exacerbated matters.

The uncooperative behaviour, the moods and outbursts of anger, that were to affect Giuseppina to such an extent that she would refuse to join him in Milan for La forza, had their origins in this period.

But Verdi’s troubles did not end there. The man who meant more to Verdi than anyone, more even than his own father, was in failing health and clearly had not long to live.

At the age of sixty-nine, Antonio Barezzi was on his deathbed. It sent Verdi into a spiral of misery and, it seems, a return of his habitual physical complaints. Giuseppina briefly kept a diary that summer, in which she wrote:

I try to raise Verdi’s spirits because of his illness, which perhaps his nerves and his imagination make him think is more serious [than it is] … He is subject to intestinal inflammation, and his craziness, his running back and forth … and his innate restlessness cause him some stomach upsets.

Inevitably it was Giuseppina, and those around her, who suffered most from Verdi’s black moods:

Also he is angry against the servants and me, so that I don’t know what words and what tone of voice to use if I have to speak to him, so as not to offend him! Alas! I don’t know how things will end, because he is steadily becoming more restless and angry … I just have to be careful not to offend him and give him the idea that I am sticking my nose in where I shouldn’t!

Giuseppina gives us there a perfect portrayal of an artist who is suffering setbacks professionally, and at the same time is grieving deeply at the loss of those closest to him.

Barezzi died at 11.30 a.m. on 21 July. Verdi and Giuseppina were at his side and, it seems, Barezzi died in Verdi’s arms. Once again, it was in a letter that Verdi gave free rein to his emotions:

Sorrows follow upon sorrows with terrifying speed! Poor Signor Antonio, my second father, my benefactor, my friend, the man who loved me so very, very much, has died! … Poor Signor Antonio! If there is a life after death, he will see whether I loved him and whether I am grateful for all that he did for me. He died in my arms; and I have the consolation of never having made him unhappy.

Given the depth of his grief, we can perhaps forgive him that last sentence, which was so patently untrue. To another friend he wrote:

He recognised me almost until the last half-hour before his death! Poor Signor Antonio! You know what he was to me and what I was to him; and you can imagine my grief. The last tie that bound me to this place is broken! I wish I were thousands of miles from here. Addio!

Giuseppina’s account of Barezzi’s death largely accords with her husband’s:

Signor Barezzi died in our arms and his last word, his last look were for Verdi, his poor wife, and for me.

Verdi, who had not been present at either his mother’s or his father’s deaths, was there for the man to whom he owed so much, whose daughter he had married. It is no wonder Verdi now compared this year to that fateful year in which he had lost his young wife, following the deaths of his two small children: ‘This [1867] is an accursed year, like 1840.’

In fact the year 1867 had not yet exhausted itself. It was on 5 December that his librettist Francesco Piave suffered the stroke from which he would never recover.

It was thus not the best time for the town officials of Busseto to raise an issue with Verdi, which they must have known would at best elicit a frosty response.

It had begun many years earlier, in fact long before he had upset them. When Verdi had first begun to make his mark in Milan, the townspeople of Busseto had the idea of replacing the small hall in the main square that was used for concerts and other gatherings with a brand new theatre, which they could dedicate to their greatest musical son.

Verdi was against the idea almost from the start – pretentious and foolish, he called it. The plan appeared to have been dropped (at least Verdi assumed it had) but in 1857 it was resurrected and the decision made to go ahead with it.

When Verdi found out he reacted with anger, which turned to fury when it was suggested to him that he had in fact been in favour of the idea when it had been proposed for the first time. Verdi’s counter-argument that it was unfair to throw words at him that he had uttered so many years ago suggests they might have had a point.

Still, nothing happened for several years, and Verdi must have thought the whole idea had once again gone away. But no, construction work began on the building, and at this point a compromise was reached with Verdi. The town promised not to involve him in the theatre in any way, if he allowed them to name it after him, the Teatro Verdi.

He grudgingly agreed, but vowed he would never set foot inside it. The building was scheduled to open with much ceremony on 15 August 1868, with a special production of Verdi’s opera Rigoletto.

Clearly hoping the maestro would mellow when the actual time came, the directors of the new theatre reserved a box for him and his wife, box number 10. The day of the opening was a holiday in Busseto, and there was much celebration.

Many of the townspeople wore green ribbons or carried green handkerchiefs, which they waved in honour of their famous son, a demonstrative pun on his name: verde meaning green. A bust of Verdi was unveiled before the performance.

As the hour approached, nervous eyes scanned the streets for the arrival of Maestro Verdi and his wife. Finally the dignitaries had to take their seats, after which all eyes were focused on Box 10.

It remained empty. Verdi had travelled with Giuseppina to the nearby spa town of Tabiano, about twenty miles south of Busseto, to take the waters and have a massage.*

He kept his word. In his lifetime he never stepped inside the theatre that was named after him, and remains so to this day.

The season of deaths had not passed. Only three months after deliberately shunning the opening of the Teatro Verdi, the composer learned that Gioachino Rossini had died in Paris. Verdi greatly admired his work and had come to know the man himself from his sojourns in Paris; it was yet another death he had to come to terms with.

But this was a fellow musician, not a family member or close friend. Verdi made the decision to honour Rossini in the only way appropriate: by proposing a Requiem Mass in which thirteen Italian composers would each compose a section. Verdi decided at the start he would write the ‘Libera me, Domine’.

It was a bold initiative, and given the complexity of numbers involved, not to mention a planning committee, bound to run into bureaucratic difficulties. There was a delay before composers’ names were announced, then delays before projected dates were settled.

Potentially most damaging of all, it was not until late in the planning process that a conductor was decided on, and the decision would lead to a raft of problems.

They could have decided on a conductor much earlier, because there was really only one name in the frame – the young conductor who had so impressed Verdi already, Angelo Mariani.

But Mariani had a raft of commitments, which he could not break. Added to this, he was suffering from health problems. When he made the planning committee aware of this, and Verdi was told, Verdi flew into a rage, writing an insulting letter to Mariani, accusing him of putting his own interests ahead of those which should come first, namely a collective honouring of one of Italy’s greatest artists.

Mariani must have wondered what he had done to deserve such a broadside, and offered to do all in his power to make the performance of the Requiem Mass possible. But Verdi was in no mood for compromise. He accused Mariani of failing in his duty as a friend, and stated unequivocally that he should not be allowed to conduct the Mass under any circumstances.

It was almost as if this whole affair was the last straw for Verdi, after an intense period in which he had had to come to terms with personal loss and professional disappointment. Giuseppina had borne the brunt of his despair; now it was Mariani’s turn to feel the full force of Verdian fury.

There was another factor that complicated Verdi’s relationship with Mariani, which until now had been one of mutual admiration and friendship.

Mariani had been working with the soprano Teresa Stolz, and had fallen in love with her. It appeared the singer reciprocated his affections, and the couple were about to become engaged. We can be in no doubt, given what was to ensue, that Verdi was also attracted to Teresa, and deeply so.

Could that have accounted for his change in attitude to Mariani? At the very least it surely added to the already tumultuous emotions he was struggling to deal with.

But an extraordinary opportunity was about to present itself to Verdi, one he could not in any way have foreseen. It would also offer the chance to send Mariani on a very long journey, several thousand miles away.

* To this day Box 10 is referred to as ‘Maestro Verdi’s box’. See Afterword.