25

SCANDAL AND COMEDY

There is a certain oppressiveness about the atmosphere at Sant’Agata, now as then. Verdi planted hundreds of tall trees, creating a small forest. This gave undoubted beauty to the estate, but it also created darkness and heaviness, still a feature of Sant’Agata to this day. We have already seen how Giuseppina complained about this in earlier years. In the winter the trees stood like skeletons, and in the summer the natural wetness of the Po valley brought rain, which clung to leaves and branches, meaning they were still dripping as the sun struggled to pierce the thick foliage.

Both Verdi and Giuseppina were prone to dark moods – in Giuseppina’s case deep depression – and the ambience at Sant’Agata did nothing to improve this.

On one occasion, she and her husband were in a small rowing boat on the large artificial lake Verdi had had dug, which was surrounded by a wall of tall trees.* One of them must have moved carelessly, because the boat tipped and Giuseppina was thrown into the water. Verdi struggled to pull her to safety, while her heavy clothes threatened to drag her under. If she had fallen in while alone, no one would have seen her through the trees.

The lake was home to a flock of black swans, which had been a gift to Verdi from Teresa Stolz. Giuseppina woke up one morning to find they had been poisoned. The mystery of how it happened, whether it was deliberate, and if so who might have done it, was never solved.

At times Giuseppina felt almost as though there was a curse over the estate, a sensation that can only have been reinforced by events that occurred some years later.

Filomena’s eldest son Angiolino, then seventeen years of age, spent three days out hunting. On his return to Sant’Agata, he laid his gun on the table and asked a maid at the house, twenty-six-year-old Giuseppina Belli, to clean it for him. When she did not immediately pick it up, he began to clean it himself. The gun was loaded and somehow during the cleaning he pulled the trigger and the young woman was fatally shot in the head.

Angiolino was arrested, charged with murder and brought before a panel of three judges. His defence was that he had forgotten to unload the gun, and that it went off accidentally. It was pointed out to him that he had ridden 14 kilometres on his bicycle over dirt roads with the gun on his shoulder, presumably loaded. Did he seriously expect his explanation to be believed?

He was found guilty but given an extraordinarily lenient sentence, just thirty-eight days in prison and a paltry fine. He appealed nonetheless, but the appeal was rejected. It is probable, though no evidence exists, that Verdi himself then intervened at the highest possible level, because no less a figure than the King of Italy reversed the sentence with a royal decree.

Verdi wrote a letter to the king, thanking him for his ‘lofty act of clemency’ on behalf of his ‘unfortunate nephew’. One untidy detail, the existence of the dead woman’s brother, who was also on the payroll at Sant’Agata, was ‘dealt with’ – the young man was given sufficient funds to emigrate.

A scandal threatened. There were rumours in Busseto that the boy was being made a scapegoat for his father, Fifao’s husband. But as swiftly as the matter exploded, it faded away. No more investigation, no further newspaper reports.

The matter was never satisfactorily cleared up; all that can be said with certainty is that somehow a major crisis was avoided. This can be attributed to the fame of the man in whose house it occurred, a multi-decorated musician who could count the King of Italy among his friends. Nevertheless the whole grim affair took its toll. Verdi wrote to Ricordi that life was like that: a rare moment of joy, then misery, sorrow, disenchantment. He said the whole family had been plunged into utter despair.

To add to that misery and sorrow, there were the deaths of close friends to cope with. Francesco Piave, responsible for ten librettos for Verdi, including his two best loved, La traviata and Rigoletto, and who had taken his share of bullying from Verdi with good grace, had died at the age of sixty-five, his last nine years spent in a wheelchair, incapacitated and unable to communicate.

An even greater shock to Verdi was the sudden and unexpected death of his oldest friend. Verdi and Emanuele Muzio had known each other for more than sixty years. They had grown up together, and over the years, as Verdi had become more and more occupied, his fame spreading across Europe and then the world, Muzio had always been at his side, ready to ease the strain. His death at just sixty-nine shocked Verdi – almost eight years his senior – to the core.

Verdi and Giuseppina were now in old age. Verdi was approaching eighty, his wife just two years younger. Both were suffering from various ailments, Verdi complaining about his joints, aggravated by the damp of the Po valley, and his increasing difficulty in walking. His sight and hearing were also beginning to deteriorate.

Giuseppina was in much poorer health than her husband. Her lungs began to function abnormally, and she had trouble breathing. She was often unable to speak for days on end. It was in stark contrast to the days when voices were continually raised, often in anger, within the walls of Sant’Agata. She spent most of her time cloistered within the house, dressed in black and moving from room to room, it was remarked, like a phantom. Husband and wife barely communicated.

In a long life full of paradox and the unexpected, Giuseppe Verdi had one final surprise for an unsuspecting world. Having finally, once and for all, decided to give up writing opera, he decided … to write an opera.

Even more surprising, it was to be a comedy. From remarks he had been making over the last couple of years to Ricordi, it was clear that the idea of composing a comedy had been revolving in his mind. Ricordi did not know how much seriousness to attach to this, but he was certainly not going to discourage Verdi. Any new composition would be welcome.

Why did Verdi settle on a comedy? We cannot be entirely sure, because Verdi never explained himself. But informed speculation can bring us close to an understanding.

Verdi had written just one comic opera in his entire career, and it flopped disastrously.

Un giorno di regno had been written nearly a half century earlier, in the aftermath of the deaths of his young children and his wife. Such a disaster had it been that it was abandoned after its opening night, after just a single performance, never to be rewritten or reworked or adapted. Had the failure rankled with Verdi ever since, simmered deep within him? It is quite possible.

There is another factor. We know it with hindsight, but Verdi knew it too: this really would be his final opera, his last offering to the world. He did not have the strength, the inclination, or the health, to compose into his eighties.

As the matter revolved in his mind, he invited Boito, who had made such a good job of the libretto for Otello, to visit him at Sant’Agata. Significantly, he warned Boito not to expect elaborate hospitality. Giuseppina was seriously unwell; there would be no convivial dinners with plentiful wine. Boito would stay just as long as was necessary for the work at hand to be accomplished.

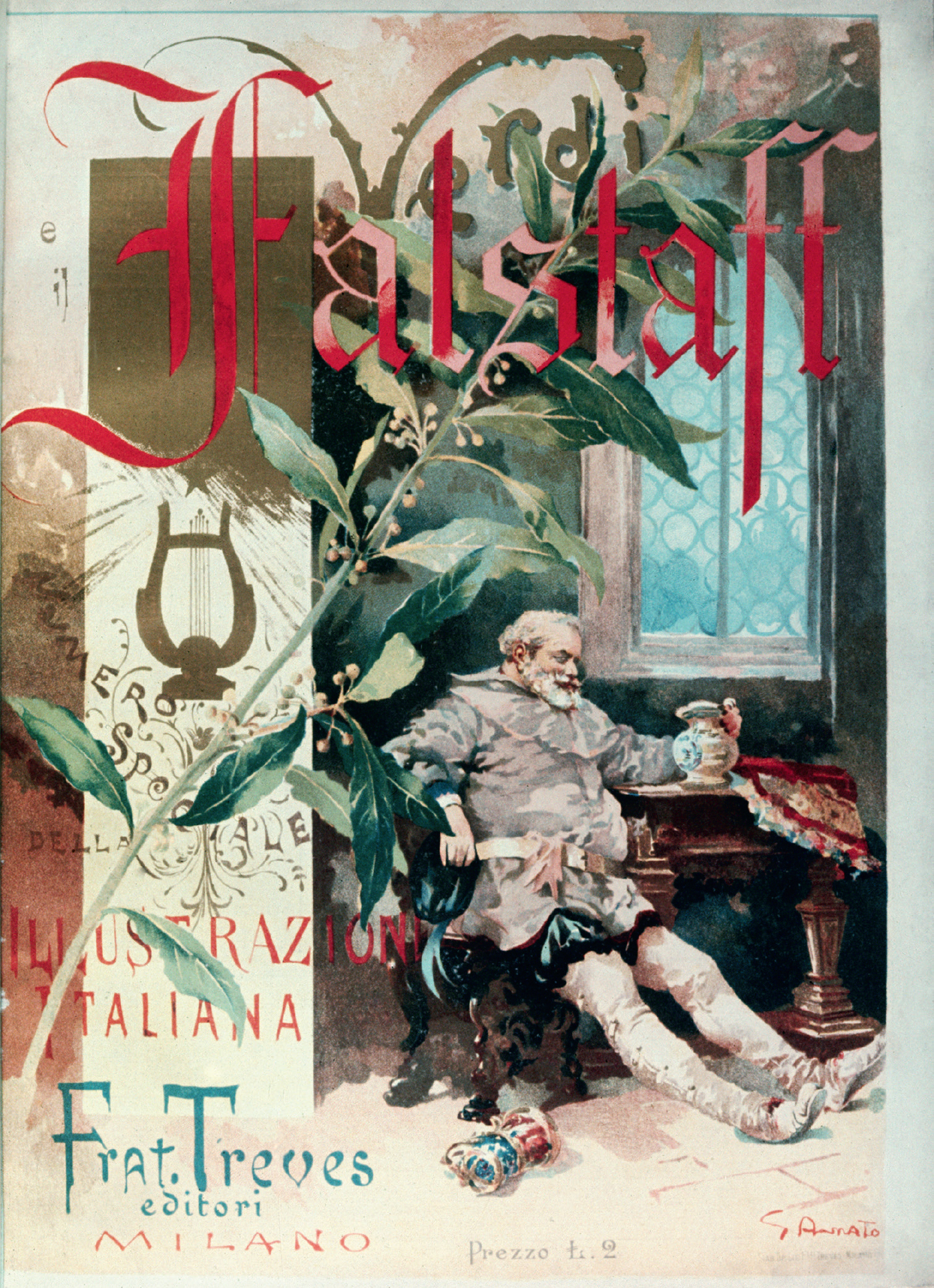

It was Boito, it seems, who came up with the subject. Given that the two of them had had such a success with Otello, why did they not turn again to Shakespeare for a comic subject? Boito’s suggestion was that Verdi should allow him to adapt The Merry Wives of Windsor, and that the adaptation should make Falstaff the central character in the opera. The comic potential of the ‘fat man’ was boundless, he assured Verdi.

Verdi, predictably, had his doubts, but he gave Boito the go-ahead to see what he could come up with.

In July 1889 Boito produced a synopsis based largely on The Merry Wives with elements from both parts of Henry IV, with the title of Falstaff. Verdi, unpredictably, was absolutely delighted with it. There were one or two points he took issue with, but in general he was very pleased.

Doubts soon surfaced, though, and they were mainly to do with his advanced years. He pointed out to Boito that he was likely to be eighty, or more, by the time the opera reached the stage. He was not even sure he would ever be able to complete it.

By this point Boito was not to be dissuaded. He wrote to Verdi:

You have longed for a good subject for a comic opera all your life, which proves you have a natural aptitude for the noble art of comedy. Instinct is a good guide. There is only one way to end your career more splendidly than with Otello, and that is to end it with Falstaff.107

Boito’s flattering words were perfectly calculated; they were exactly what Verdi needed to hear. Comedy was the one area – the sole area in all opera – in which he had failed. If he could pull off a successful comedy, then he would have proved himself the master of all operatic forms.

Verdi responded in a way none of his previous librettists had ever enjoyed:

What a joy to be able to say to the public, HERE WE ARE AGAIN!! COME AND SEE US! … Amen, and so be it! Let us then do Falstaff. Let us not think now of the obstacles, my age and illness! But I want to keep it the deepest secret, a word I underline three times to tell you that no one must know anything of it.108

And a secret it was kept. Not even Giuseppina knew, at least at the start. Gone were the days when Verdi confided in his wife, asked for her advice, discussed projects with her.

He made several trips to Milan. Did he go to see Teresa, herself now in her late fifties and not in the best of health? Did he discuss the possibility of a comic opera with her? We can only speculate. He was a lifelong master at covering his tracks.

Unusually for Verdi, he began composing almost immediately. It seemed his mood matched the subject matter. It is easy to imagine him writing his comic opera with a smile on his face. He wrote to Boito:

I’m amusing myself by writing fugues! Yes, sir, a fugue: and a comic fugue which would be suitable for Falstaff.109

He did not know it yet, but that fugue, once completed, would provide a glorious finale to the entire opera, indeed to his own operatic life.

Perhaps Verdi needed to believe that this was not a serious attempt to write opera; after all, he had given all that up, hadn’t he? When finally he decided to tell Ricordi what he was doing, he described it in such a way that he could at any moment decide to abandon the whole thing, without repercussions:

I am engaged in writing Falstaff to pass the time, without any preconceived ideas or plans. I repeat, ‘to pass the time’. Nothing else. All this talk, these proposals, however vague, and this splitting of words, will end by involving me in obligations that I absolutely refuse to assume.110

Unlike poor Piave – and he was not the only one! – Boito found Verdi thoroughly accommodating. The composer accepted the libretto almost without alteration.

Again unusually for Verdi, he worked at the opera over some considerable time, devoting several weeks to it, then breaking off, before resuming again. It was as though he needed periodic stimulation away from the keyboard and manuscript paper.

It was a full two years before Verdi produced a workable version of the opera, and even then the orchestration was not complete. But the bulk of the work was done. In yet another departure from his usual process, he seemed to have maintained his sense of humour throughout the process, not falling prey to his usual psychosomatic illnesses. This, despite articulating the fear to Boito that he might die before completing the opera.

He dispatched the (almost) finished object to Ricordi with a humorous note addressed to the eponymous hero of the opera:

Tutto è finito, |

All is finished. |

Va, va vecchio John. |

Go, go, old John. |

Cammina per la tua via |

Go on your way |

Fin che tu puoi. |

As long as you can. |

Va, va |

Go, go, |

Cammina, cammina, |

On your way. |

Addio |

Addio.111 |

Verdi had been done proud by his librettist. Boito had transformed Shakespeare’s play once again, telescoping the action, amalgamating certain characters, developing the characterisation – all in all, presenting Verdi with exactly what was needed for him to set it to music.

It really does seem as though Verdi, for once, was relishing the challenge. When he arrived at La Scala to supervise rehearsals, it was remarked on how energised and lively he was, how he was in control of every aspect of the production, and – most remarkably, perhaps – how easy he was to work with. This was a new Giuseppe Verdi; the Bear had remained in Busseto.

The opening night for Falstaff was set for 9 February 1893 at La Scala. For the occasion, he brought his Peppina from her sick bed. He knew there would be no more premieres; he wanted her to be at this one. Teresa Stolz, we can be sure, was not there.

As with Otello, the anticipation was enormous, overwhelming even. Music critics and opera lovers came to Milan from all over the world. Verdi had installed Giuseppina in their usual suite in the Grand Hotel. From there she wrote to her sister, somewhat caustically:

Admirers, bores, friends, enemies, genuine and non-genuine musicians, critics good and bad are swarming in from all over the world. The way people are clamouring for seats, the opera house would need to be as big as a public square.112

Again, as with Otello, a succès fou was guaranteed. By now Verdi could do no wrong in the eyes not just of his countrymen but of the world. Here was Italy’s greatest operatic composer, at the end of his glorious career, offering one final jewel.

During the performance, Verdi was called on to the stage time and time again. Once more he brought Boito on to share the applause with him; once more he was mobbed as he left by a side door; once more he was called out on to the balcony repeatedly.

Falstaff, only the composer’s second comic opera, was a triumph. He had proved there was nothing he could not do, nothing he could not turn his hand to.

There are so many tunes in Falstaff, so many melodies, that I have seen it described as having none. Verdi rarely repeats a melody, and is in fact more inclined to discard it without even developing it. A lesser composer would milk each melody for all it is worth. This was Verdi truly at the top of his powers.

The single passage in Falstaff that stands out, both musically and as a commentary on Verdi and his philosophy on life, comes, fittingly, right at the end of the opera. Falstaff leads the ensemble in a scintillating comic fugue: ‘Tutto nel mondo è burla’ (‘All the world’s a joke’).

As Verdi’s final composition (though, as we have seen, it might well have been the first part of the opera that he wrote), it is matchless. This is Verdi looking back on a long career, which had its failures as well as successes, as though he is saying, ‘So what? What does any of it matter anyway?’

In the audience at La Scala that night was another Italian composer of opera, a younger man aged thirty-five by the name of Giacomo Puccini, whose latest opera Manon Lescaut had received its first performance to huge acclaim in Turin just one week earlier.

Verdi was aware of the younger man making waves, and had been somewhat critical after seeing his early work Le Villi:

[Puccini] follows modern trends, which is natural, but he keeps to melody which is neither ancient nor modern. However the symphonic vein appears to predominate in him. No harm in that, but one needs to tread carefully here. Opera is opera and symphony symphony and I don’t think it’s a good thing to put a symphonic piece into the opera merely to put the orchestra through its paces.113

In one sense, damning with faint praise; in another, perhaps, the understandable envy of an older composer for a much younger one with, clearly, a fine career ahead of him.

There is no other comment in any of Verdi’s correspondence on the man regarded from the start as his successor; nor am I aware of any opinion on Verdi expressed by Puccini. But we can be in no doubt as to Puccini’s admiration for the older man. Four years after Verdi’s death, Puccini would compose a Requiem to be performed in his memory.

As for composers admired by Verdi, one name stands out. When a festival was being planned in Bonn to honour its most famous son, it was proposed to Verdi that his name should be added to the honours list of musicians at the birthplace of the great man.

Verdi replied:

I cannot refuse the honour that is offered to me. We are talking about Beethoven! Before such a name, we all prostrate ourselves reverently.

* It remains a very attractive feature of the estate today.