It is no coincidence that the largest number of posters in the ‘Recruitment’ category are British. Before 1914, both France and Germany had obligatory military service for men, so that in August 1914 the French army already numbered 1,300,000 men, including colonial troops. The German army was even bigger, comprising in 1914 almost 1,750,000 men, and there were a similar number in reserve, as all men between the ages of 17 and 45 were required to undergo compulsory service. These were significant figures compared to the size of the British Regular Army at the outbreak of the war, which was a little over 710,000 strong including reserves, and of these only 80,000 men were sufficiently equipped to go to war. The majority of the army was spread thinly across the world, policing Britain’s far-flung colonial interests. In part the reason for this was that the British had always been opposed to conscription, and even the idea of retaining a standing army was a contentious one.

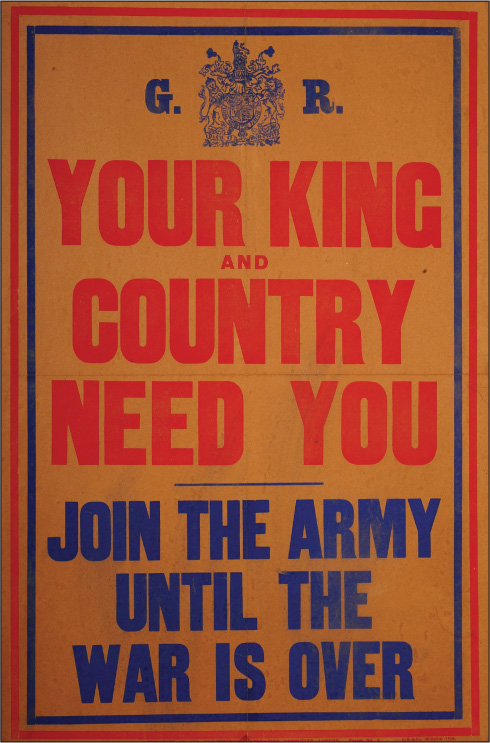

Initially, 100,000 volunteers were asked for in a direct appeal by Lord Kitchener, fronted by the famous ‘Your Country Needs You’ poster, which was issued on 7 August 1914. The government believed that any more men would simply cause logistical problems, but in the event such was the rush to join the colours that by January 1915 over a million men had volunteered. The initial belief of the British high command that the war would be short and sharp soon vanished in the smoke of the battles of 1914. It soon became painfully clear that far more men would be needed than had ever been thought possible. In France the British Expeditionary Force had lost 90,000 men in the first three months of the fighting – more than its original size, although curiously the near-defeat of British forces in the early battles such as Mons helped fuel enlistment. Nevertheless, the government was becoming increasingly uneasy about the rate at which men were being killed and wounded, and the inability of the army to replace them. This, of course, was not unique to Britain: French and German losses in 1914 had also been huge, but those countries still held sufficient reserves for the numbers to be made up. Britain’s problem was that by late 1915 the rate of volunteering was slowing, for by then the numbers of men enlisting had dropped to around 70,000 per month. This was not enough to maintain the level of manpower needed, and both posters and other popular media such as music halls were used to recruit more young men. The tone of the posters being produced began to change from straightforward patriotic pleas to ‘Fight for King and Country’ to more subtle messages. Imagery became more frightening and graphic as propaganda became better organised. Rumoured German atrocities, the threat of invasion and even the capture of civilians and implied rape appeared on billboards around the country. There was little doubt that such methods were needed as the war progressed. Conscription had to be introduced in January 1916 for single men but even this was insufficient: the Somme battles alone, for example, required 3,000 replacement soldiers per day. In the United States the army was sufficiently large, at 98,000 men, to send troops to Europe as soon as hostilities were declared, so that there were 14,000 Americans in France by June 1917 with an additional 25,000 arriving every week. By the summer of 1918 a million American servicemen were in France. In part these numbers were attainable only through conscription, but this did not prevent the American government from embarking on a huge poster campaign to encourage voluntary enlistment, but generally such posters tended to be aimed less at enlistment and more at promoting the war effort. It is doubtful whether recruiting posters had any effect whatsoever in any country by late 1917, although they continued to be produced. Without the United States’ entry into the war, it is questionable how much longer Britain and France could have continued hostilities. Unlike weapons or money, the numbers of soldiers that could be created was finite.

‘Order of general mobilisation.’ A simple administrative poster with two flags announced the French general mobilisation. Each mayor had received an envelope containing several copies. When the Prefect gave the order, the envelope would be opened and the exact date would be added. The image of French soldiers happily going off to war with flowers attached to their rifles is largely a myth. Despite small nationalist demonstrations in Paris, most of the population, still very rural, regretted not being able to harvest the crops. The overall feeling was one of quiet determination to defend country and family against what was perceived as German aggression.

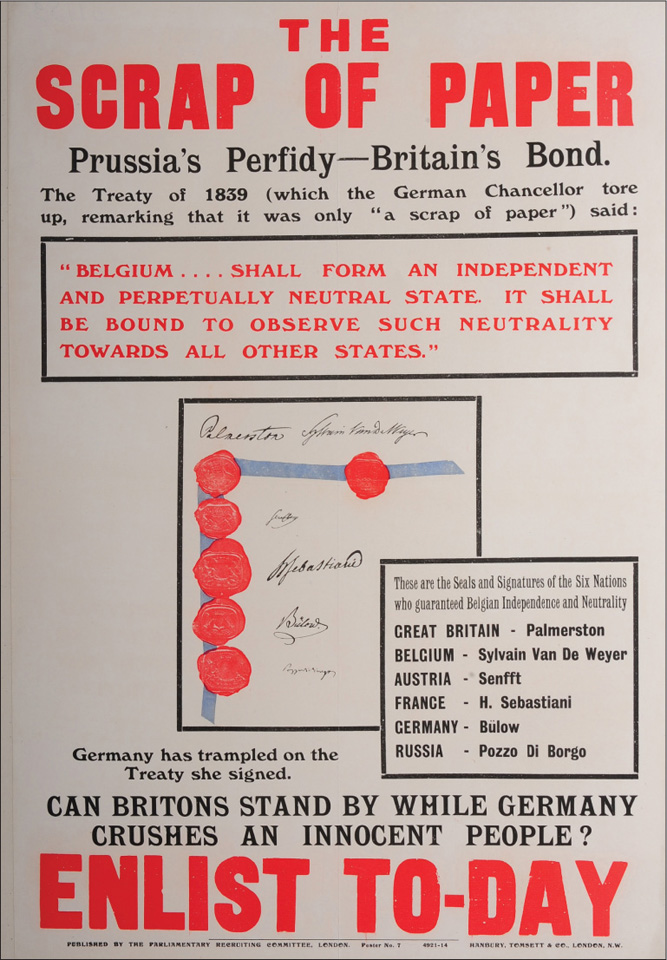

An early poster outlining the Treaty of Belgium and highlighting the apparent indifference of the German Chancellor to its content. The fact that the treaty was signed thirty years before the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and bore little relevance to the politics of 1914 was carefully ignored. The appeal was to the emotions rather than to historical accuracy.

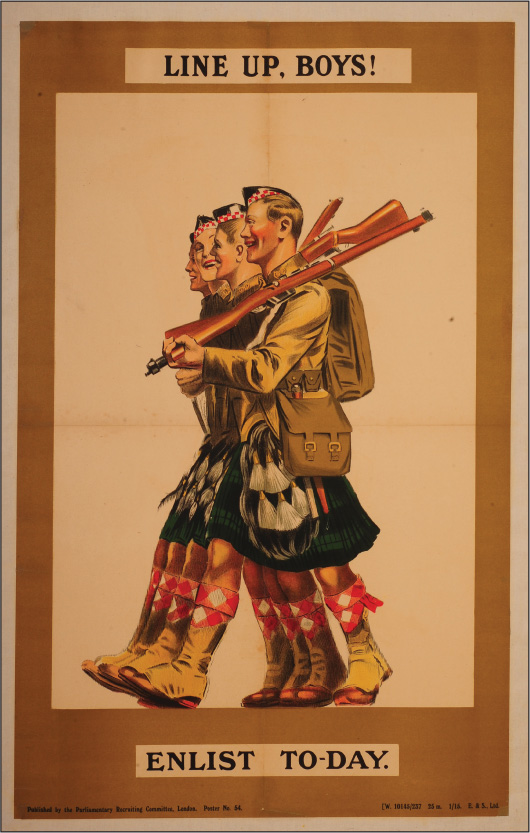

Another reference to the ‘Scrap of Paper’. The detail in this 1914 painting by war artist Clarence Lawson Woods (1878–1957) is worth a second look as the rather pensive-looking Highlander’s uniform and equipment have been very accurately reproduced, an unusual feature in posters of this type. The explanation is that Wood had served in the army as a Kite Balloon officer, and was decorated for gallantry. He worked for the Graphic, the Strand, Illustrated London News and Boy’s Own newspaper but after the war he became a recluse. However, his lifelong concern for the welfare of animals earned him a fellowship of the Royal Zoological Society in 1934.

Although the artist is unidentified, this is the first depiction of John Bull in a military poster, and dates to 1914/15. Created in 1712 by Dr John Arbuthnot, ‘John Bull’ represented a typical simple, good-hearted English yeoman, not particularly heroic but always adhering to the British sense of fair play. He proved to be the ideal representation of the ordinary Englishman and was to appear regularly in posters during the Great War, being represented in the United States by the figure of Uncle Sam.

This is one of the simplest but most often reproduced recruitment posters of the war. The message is clear and unmistakable, and examples were reproduced in varied sizes: as huge bill-hoardings, large shop-window posters and newspaper pages. They were everywhere, and are still one of the most commonly found posters of the war, although in many respects the sentiments today would no longer be thought of as relevant.

A more subtle poster, pricking the conscience of the ordinary man in the street, this embodies many elements of later posters, particularly the fourth item, which pre-dates the later, famous, ‘What Did You Do In The War?’ poster. It plays on the fact that men who did not join up would have to wrestle with their consciences in later life.

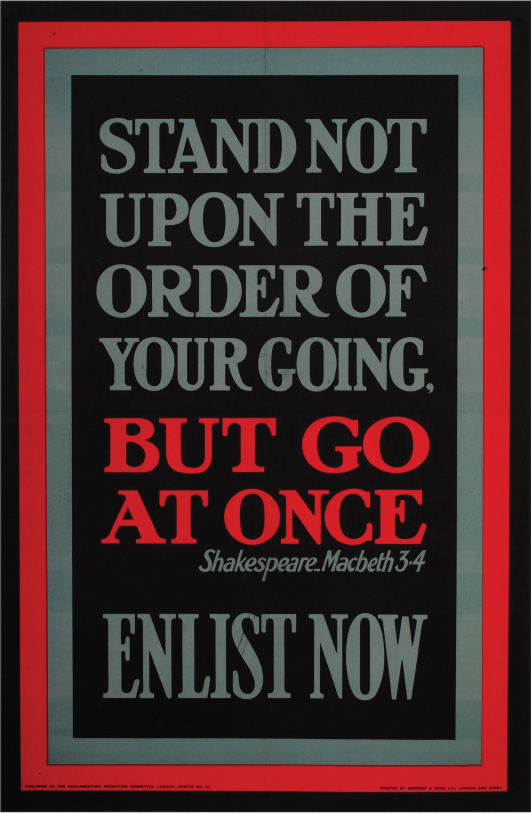

A rather unusual literary example, quoting Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth (Macbeth, Act 3, Scene IV). Although it is arguable that the message would be lost on many of the ordinary public today, in Edwardian England Shakespeare was taught in schools and widely read, and it would certainly have struck a chord with many of the men at whom it was aimed.

Another early poster of about 1915 using an emotional appeal, this time purportedly from the children of England. Although now the concept of children urging their fathers and brothers to go and fight seems inconceivable, it must be remembered that to the Victorian generation of 1914 God and the mother country were sentiments that were taken very seriously indeed. The small quote at the bottom from Admiral Lord Nelson, ‘England expects ...’, is a nice additional touch.

The practical terms and conditions for men enlisting were little understood, and the army was regarded by all but the lowest class of men as a very poor choice of career. This poster tries to redress this somewhat by spelling out the financial benefits. At a time when prospects for working-class men were a life of long hours (the average working week in 1914 was 58 hours), low pay (average weekly pay was 16 shillings 9 pence) and little chance for economic or social advancement, the ability to join the army, be well fed and adequately paid as well as seeing foreign countries was a tempting one. Indeed, pay of 21 shillings a week for a married man with two children was a not unreasonable income.

This poster follows on from the previous one, depicting a well-fed, healthy-looking soldier, expressing his delight with army life. Bearing in mind one-third of the working class males who enlisted in 1914 were recorded as being malnourished, this simple poster must have had considerable appeal. It is signed only as ‘OR’, and the artist is unidentified, but the poster is dated June 1915. The title duplicates a very popular musichall song of the time.

This clever image crosses all social boundaries, showing men from every possible class – upper, legal, white collar and blue collar – queuing up to enlist and gradually being transformed into a cohesive armed force. In practice, having to deal with a new type of volunteer soldier, who was more intelligent and better educated than traditional recruits, posed significant problems for the army in 1914.

In a similar theme, there was plenty of space in the army for any able-bodied man to fill. The prime reason that they were needed – because of the steadily rising numbers of casualties – was omitted. During the Somme offensive replacement men were needed at the rate of 3,000 per day.

Certain visual images and themes recur in posters during the war, and uniform and equipment (in this instance, a cap) is one of them. The expression ‘If the caps fits’ was a commonplace one and here it has been adapted to encourage men to volunteer.

This illustration is an interesting one: its visual appeal seems more suited to manufacturing than it does to fighting, and it is a curiously Germanic image. It is a rare poster and does not appear to have been produced in large numbers, perhaps because it did not produce the desired result.

This interesting depiction of the uniform and equipment carried by the average infantryman is a Parliamentary Recruiting Committee poster, probably dating from 1915, as no steel helmet is shown. What is curious is the request ‘Be honest with yourself’, the meaning of which is rather open to interpretation. Possibly the viewer was supposed to feel guilty about not being in uniform.

Another variation on the theme of headgear, which would have meant much more to the men of 1914, when social classes were differentiated by hats. In this image the headgear (clockwise from top left) represents the boater of a student or young man, the straw hat of a man-about-town, the top hat of the upper and professional classes, the trilby of a middle class man and the bowler of a working man. Oddly, the universally worn cloth cap, the badge of the working class, is not represented here.

Another 1915 poster, this time from January, with more smiling soldiers. The image, reminiscent of a Boy’s Own comic illustration, creates an impression of great bonhomie, and the red-cheeked laughing Highlanders imply that the war was really a jolly affair, which may have been appropriate in 1914 but was far removed from the truth by 1915.

Maps feature quite frequently on wartime posters, but this is an unusual image that makes use of two posed figures that have been photographically reproduced across a map of southern England and northern France. The simple message – that a man could virtually step across the Channel and fight – belied the complex process of recruiting, training and equipping a vast civilian army but the image is nonetheless dynamic and uses a technique that is very modern in its application.

The event depicted here enables this poster to be accurately dated, for it recalls the shelling by the German fleet of Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby on 16 December 1914. The attack resulted in 137 deaths and 592 injuries, and sparked massive outrage in England. Finely painted by Lucy Kemp-Welch (1869–1958), it shows an angry Britannia pointing her sword across the water, while the town of Whitby blazes behind her. A very talented landscape artist, Kemp-Welch also specialised in horses and provided the illustrations for Anna Sewell’s famous book Black Beauty.

A simple but effective map of the British Isles used here not only as a recruiting guide, but also as a visual indicator of the area that was under potential threat from an aggressive enemy. By showing the whole of the British Isles, it made the threat from Germany appear even more dangerous, for the implication was that nowhere was safe from possible German invasion. Similar maps were used in the United States to reinforce the threat, real or imaginary, to their freedom.

E.V. Kealey’s famous image from May 1915 shows a distraught-looking family watching their menfolk march away. To an extent it parallels the earlier poster, ‘From the children of England’. At this early stage in the war there was little role for women to play, and they were usually depicted as helpless victims. This changed dramatically once the war industry gathered pace after 1915 and women became an integral part of the manufacturing workforce. Little information survives about Kealey’s career but he was a prolific poster artist and produced several important works for the war effort.

It is seldom possible to identify individual British poster artists (German and French artists tend to be more readily recognisable), but Clarence Lawson Wood was a prolific poster artist and produced a number of excellent images, such as this popular and rather touching painting from 1914. The ‘chip of the old block’ phrase seems to indicate a father saying goodbye to his son, and the use of the image of a veteran of earlier wars is both poignant and slightly heroic.

This recruiting poster, produced by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee in April 1915 and executed by W.H. Caffyn, better known for his fine pen and ink portraiture, shows a smiling Tommy and bears more than a passing resemblance to cartoonist Bert Kent’s famous nameless soldier in ‘’arf a mo’, Kaiser’. The sentiment at the bottom – ‘there were smiling faces everywhere’ – is straight from the pages of one of the boys’ comics, for by the time of this poster the gritty reality of war was well understood by the front-line soldier.

In 1914 much was made in the British press of the ‘Rape of Belgium’, with lurid accounts (not all of them false) of German atrocities against innocent civilians. This 1914 poster exhorts the reader to remember what the Germans were capable of, and as the grim-faced British soldier stands guard over the fleeing civilians, the child points to him with a hopeful expression.

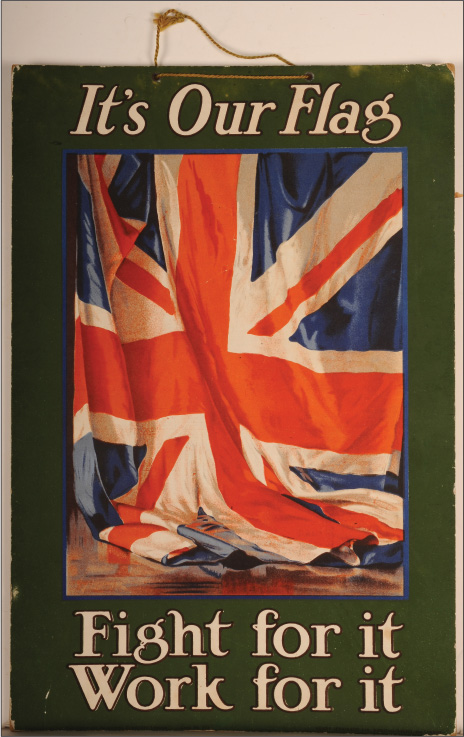

A direct appeal to work and fight for ‘Our Flag’. The concept of fighting for the flag of one’s country is as old as warfare, and still meant a great deal in 1914. By the end of 1916 such overt jingoism had faded and while the soldiers of all sides still fought, the war had become something to endure and be seen through to its logical conclusion. National idealism was no longer a relevant emotion.

Another of the series of posters by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, this is a very simple and graphic image, and possibly the first to depict men going ‘over the top’ in battle. It is strikingly similar to the famous Boer War photograph of Canadian troops advancing up a hill during the Battle of Colenso.

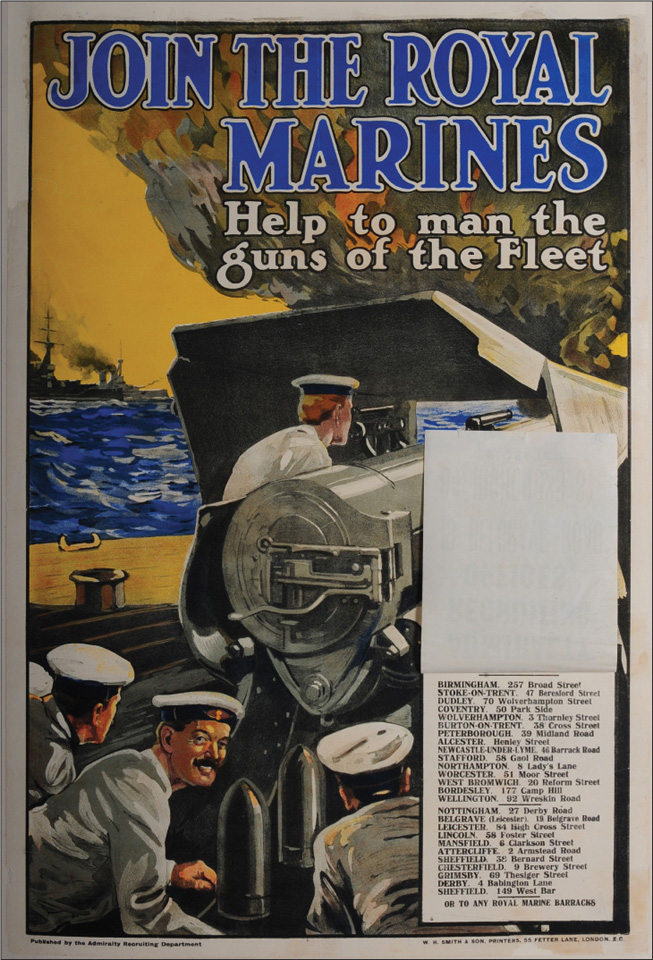

Not many British posters were produced that were directed at getting men to join specific units. Depending where he joined up, a 1914 volunteer was usually allocated to his county regiment, although this changed as the war progressed and casualty levels rose. This Admiralty poster specifically attempts to get men to enlist in the Royal Marine Artillery and helpfully lists all of the recruiting stations, while a slightly manic-looking gunner grins at the viewer.

Another direct message, this time using no artwork at all, but appealing to the Englishman’s sense of pride in being a ‘free man’, not a medieval serf or slave. The implication, of course, was that failing to fight could once more lead Britons into slavery.

Lord Derby’s Scheme was a half-measure introduced prior to the government accepting that conscription was inevitable. On 11 October 1915 Lord Derby was appointed Director-General of Recruiting and on the 16th he introduced the Derby Scheme for raising large numbers of volunteers. Men aged 18 to 40 could continue to enlist voluntarily, or attest at a recruiting office and return to their civilian occupations, but were obliged to enlist when called up. The War Office stated that voluntary enlistment would cease on 15 December 1915. Men who had registered under the Derby Scheme were classified into married and single, and into twenty-three groups according to their age. The scheme eventually raised 2.4 million men.

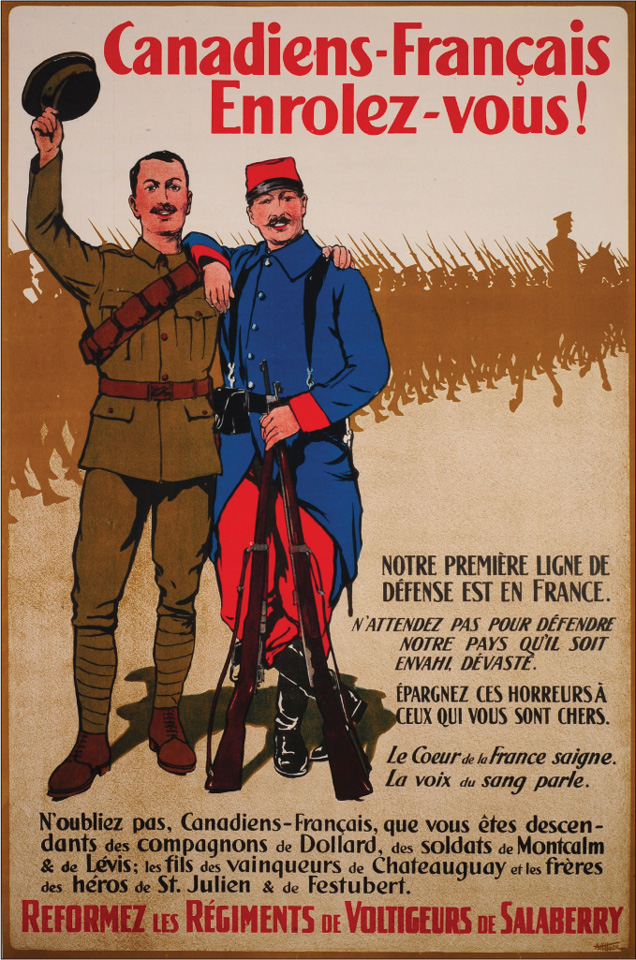

‘French Canadians Enlist!’ Thousands of French Canadians flocked to join the army in the wake of the German attacks of 1914, and several French language posters were produced. At the outbreak of war the entire Canadian Regular Army numbered only 3,000 men. This poster by Arthur Hider (1875–1952) exhorts French Canadians to enlist to protect their language and institutions, and to recall that they are descended from the soldiers of Generals Montcalm and Levis. Not relying simply on the power of history to draw men into the ranks, the text also makes note of the ‘brothers’ of the early battles at St Julien and Festubert in 1915.

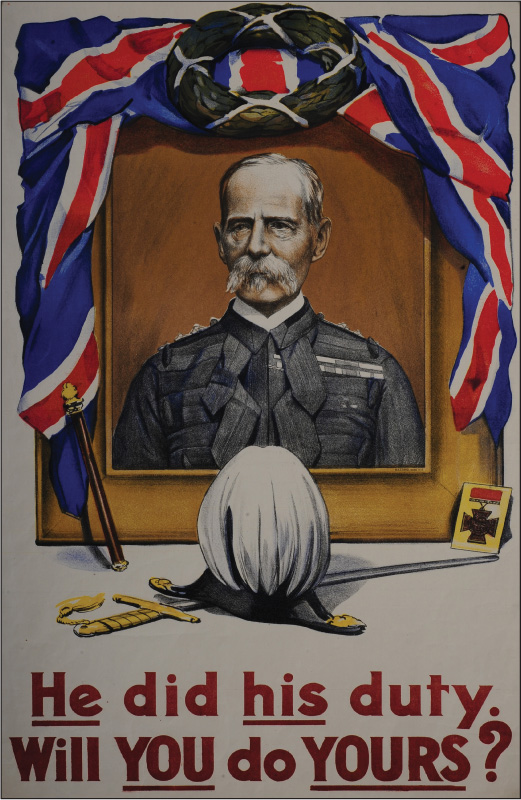

A very patriotic flag-framed image of Lord Frederick Roberts, who won the Victoria Cross during the Indian Mutiny of 1857. He was largely responsible for defeating the Boers during the Second Boer War (1900–1901), and became the hero of a generation, much as the Duke of Wellington had been a century before. His death at St Omer in France while visiting Indian troops on 14 November 1914 only served to raise him even higher in the nation’s regard, and the use of his image here was a subtle one.

Although it is generally believed that the United States did not join the war until 1918, hostilities were begun with Germany on 6 April 1917 and there were some US troops in France by the time of the Battle of Cambrai (21 November 1917). This poster was one of the first to be printed and its flag-waving soldiers hark back to the age of the American Revolution – hardly a reflection of the reality of the war that the United States was soon to find itself embroiled in.

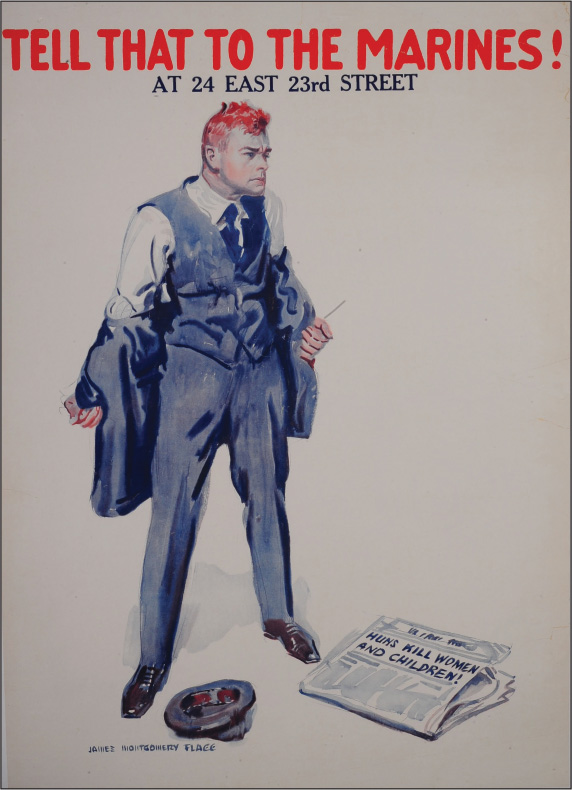

This poster is interesting for several reasons. The artist, James Montgomery Flagg (1877–1960) was the originator of the famous Uncle Sam figure in the hugely popular ‘I want you for US army’ posters, and he based Sam’s face on his own. There is also a covert message in the newspaper headline ‘Huns kill women and children’, reflecting the popular outrage in the United States over the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915, in which 128 Americans died. This act, indefensible in their eyes, was to set the US on a collision course with Germany. The title of the poster was an expression first recorded in 1806 – ‘You may tell that to the Marines, but I’ll be damned if a sailor will believe it’ – implying a tale that was just too tall to be believed, and the expression has now passed into modern idiom.

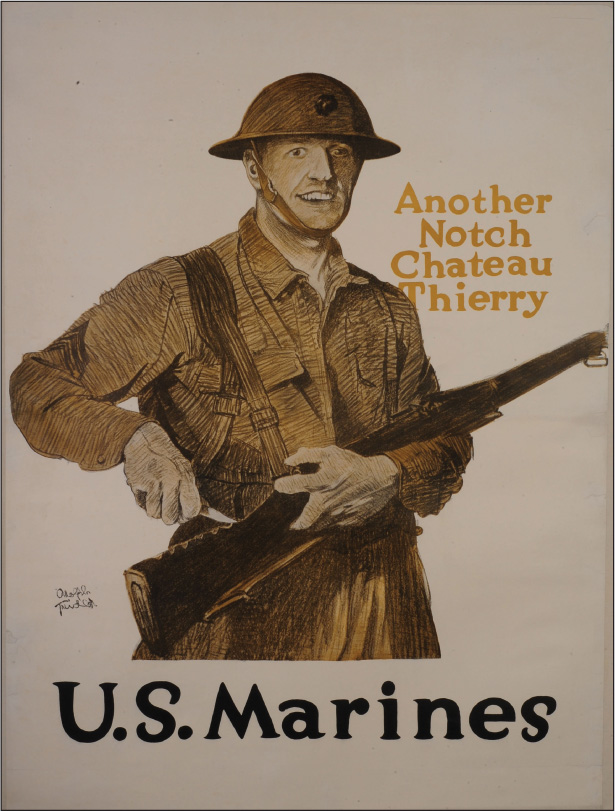

The Marines always prided themselves in being at the forefront of the fighting, and this simple but fine drawing by Adolph Triedler (1886–1981) pays homage to their fighting spirit, and refers to one of the earliest, and largely successful, actions of the American Expeditionary Force at Château-Thierry on 18 July 1918. The soldier is depicted cutting a notch on his rifle butt, indicating one more win for the AEF. During the Great War Triedler specialised in depicting women war workers and was to have a very long and extremely successful career.

The US Navy was not as heavily involved in the war as their land forces, but the unrestricted U-boat campaign of 1917 was costing many American lives. Between April and June shipping losses amounted to 1.96 million tons and Britain’s wheat stocks were reduced to just six weeks’ worth. It was quite conceivable that at some stage the Imperial German Navy might well meet head-on with US warships, so navy recruitment was taken seriously. The message of this poster is simple and the slightly cartoon-like image by a little-known artist, George Wright, evokes both a sense of excitement and purpose.

The army was quick to respond to the demands placed on it, and this poster from 1917 is unusually location-specific, showing the US Army officer training camp at Plattsburg, NY, which had been opened prior to the US entering the war. It was one of several posters produced on behalf of the Military Training Camps Association, and at least two others feature Plattsburg.

This is arguably one of the most haunting and best known of all the recruitment posters issued during the war. Painted by Augustus Savile Lumley (1878–1949) in late 1914, it is a brilliant example of subtle emotional blackmail. The idea for the image came from the printer Arthur Gunn, who asked his wife that very question one day, having imagined himself as the father in question. The following day he asked Lumley to do a preliminary sketch. Shortly afterwards, Gunn joined the Westminster Volunteers and served throughout the war. Lumley went on to become a very highly respected book illustrator, as well as an artist for Boy’s Own and Champion comics. A very similar version of this poster was reissued in the Second World War.