When war was declared in August 1914, the duration of the fighting was not seriously considered by the combatant nations. The belief that it would be a short, sharp conflict was a universal one, although a few lone voices warned of the possibility of a war that would last for years. Few heeded them. When the lines stagnated in the winter of 1914 it became gradually apparent that there was not to be a decisive breakthrough on either side. Of all of the industrialised nations, Germany had the strongest economy, with the largest manufacturing output, second in the world only to that of the United States. Despite this, the German and Austrian war economy was severely disadvantaged by its reliance on its export trade with the rest of the world, and this trade had collapsed during the fighting. Most of what Germany needed to wage war had to be imported. She had no stocks of rubber, cotton or ores and few chemicals, and was largely excluded from trading on the international financial markets.

As the economy slowed, the German government attempted to increase its income through public war bonds or Kriegsanleihe . Nine issues were made during the war, boosted by the extensive use of poster propaganda. This worked initially, and over the course of the war some 100 billion marks were raised, but as shortages of food hit home, so public confidence in the economy and the government faltered and the domestic crisis worsened. The problems were exacerbated by the conscription of so many farmers and land workers into the army, and the British naval blockade. So short of food was Germany that the winter of 1916/1917 was known as the ‘turnip winter’, as that vegetable was almost all that was freely available. Some 750,000 Germans died of malnutrition during the war, and by 1918 the government was unable to repay the interest on the bonds.

In 1914 Britain had a flourishing economy, with strong export trade; while this was much reduced during the war, it was still possible for Britain to continue trading. Most of what was required was available from countries friendly to the Allied cause – beef from Argentina, ores from South America, rubber from Malaysia. However, the war economy and the need to fund an army of over 5 million men placed an unsustainable burden on the economy, so a system of offering guaranteed short-term public loans that had originated during the Napoleonic wars was revived in November 1914. These war loans proved very successful, partly because of public confidence. The British public, unlike in Germany, had greater faith in their government and had suffered fewer privations as a result of shortages; they also believed that the Allies would eventually win the war. Although £2.75 billion was raised by the war loans system, the national debt increased from £650 million in 1914 to £7.4 billion by 1919, much of which was owed to the United States. To give some indication of how huge the debt was, the outstanding amount of war bonds still to be repaid stands at £31,939,000 (as of 2012).

In common with most industrialised nations before 1914, the French economy was also buoyant. However, the German-occupied territories contained 58 per cent of the steel and 48 per cent of the coal that France required for its war production. This placed France in a financially impossible position, as much of the materiel that was needed had to be imported and paid for in hard currency, and by late 1916 she also had an army of 6 million men to be paid for. Ever more money was required to meet the mounting national debt, so the government began to offer war loans similar in form to those in Britain, although generally of a longer-term nature. They too used a striking series of posters aimed at persuading the public to invest in the war as an act of patriotism. The problems in repaying them were, of course, the same as those faced by all the other belligerent countries, in that eventually the cost of repayments spiralled out of control. Most of the loans were repaid at only 25 per cent of their face value as inflation and changes of political policy eroded their worth.

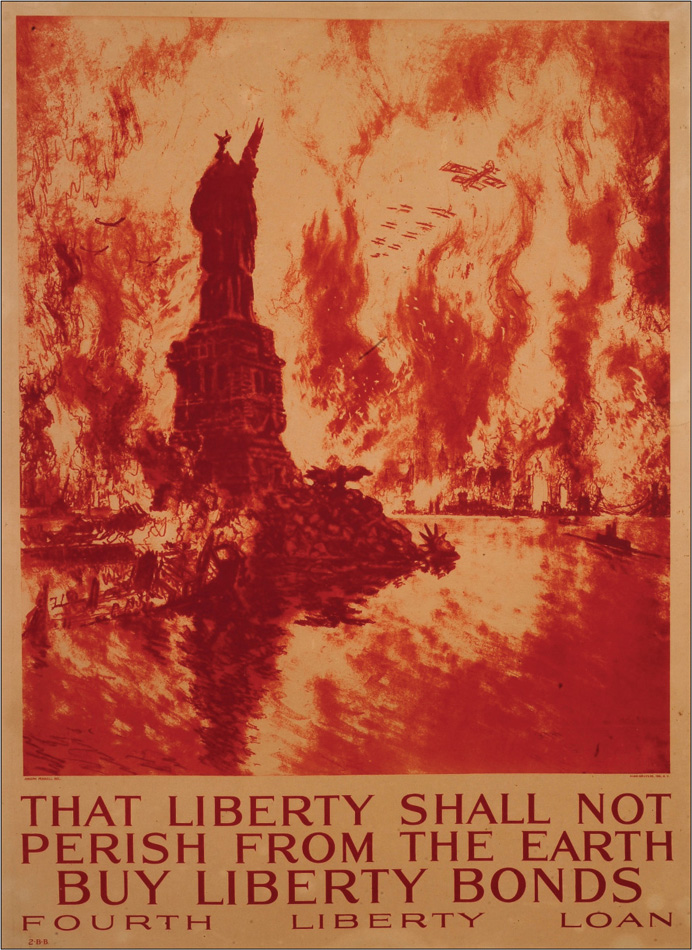

The United States was probably the most successful country in regards to financing their war effort, aided, of course, by having the largest world economy. In early 1917 the American government began issuing Liberty Bonds to raise capital, and this policy was aided by a very aggressive advertising campaign in conjunction with the Committee on Public Information to ensure the bonds became popular with the public. However, as with the campaigns in other countries, the money raised ($21.5 billion dollars) was mostly from financial institutions and corporations, and postwar examination of the War Bond Campaign showed that it actually attracted very little public support. In fact, this proved to be true for all of the countries that attempted to raise money from the public, for despite the very broad range of posters that were produced, which incorporated elements of propaganda, coercion and emotional blackmail, they did not achieve the desired result. However, they did leave behind an extraordinary legacy of art for future generations.

‘For France give your gold. Gold fights for victory.’ Half of French war spending was covered by loans. This enabled the government not to raise taxes, despite the mounting demand for credit. Posters became an essential means for this financial effort. Abel Faivre was one of the few French artists who did not fill the entire background but let the main elements stand out. His simple messages derived from his experience as a caricaturist. For the first French National Defence Loan launched in November 1915, he turned a catchphrase into a literal meaning. The complex nature of the war effort is reduced to its unique goal: defeating the German Army.

‘Subscribe to the 5.5% war loan. The more money there is, the more munitions there will be!’ Though the Russian forces were often considered to rely solely on sheer numbers, the country’s industrial and military power was growing fast by 1910. Artillerymen were particularly proud of their artillery fuses, a technological marvel of the time. However, the munitions crisis was especially severe in Russia from 1915 onwards. This battle scene, with the exceptional smouldering shell craters, gives an intense sense of emergency that is reinforced by the direct gaze of the soldier.

‘The best savings bank: the war loan!’ Here Louis Oppenheim has created a visual short-cut by having bank notes going directly to the army, once again symbolised by a steel helmet. At a time when getting change was difficult, the wording on the poster was all the more reassuring for the population. As it turned out, the war loans were often for a five-year period. By 1923 the German state couldn’t reimburse them when they expired. It resorted to printing new bank notes but this caused massive inflation. By November 1923 one dollar was worth 12 thousand billion German Marks. Small stockholders were ruined.

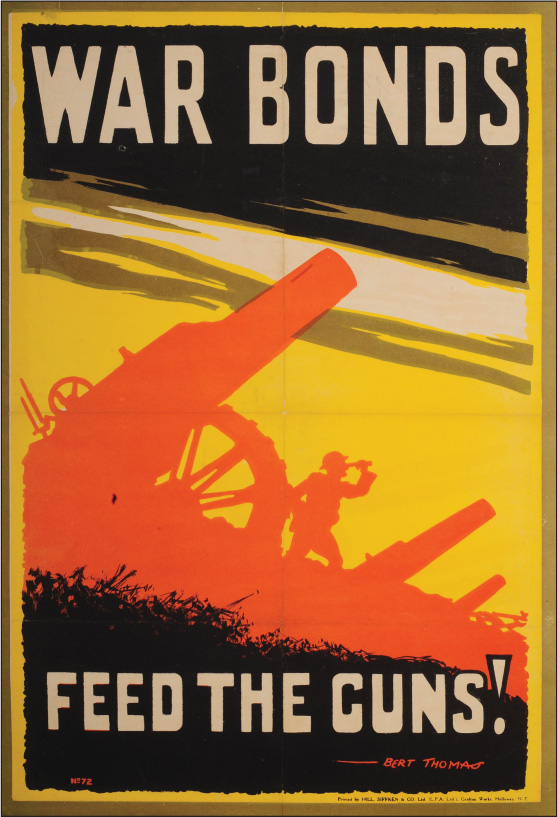

The war was to prove more costly than the British government could possibly have imagined and alternative sources of funding were soon needed. War Bonds were a debt security issued by the government, originally conceived under the term ‘Consols’ as a means of helping refinance the debts incurred in the Napoleonic wars. They helped to generate vast sums of money during the war years – £1.54 billion in the case of the First and Second War Loans. The line-up of guns reinforces the link between funding and manufacture.

This poster shows a particularly aggressive link between purchasing war bonds and the use of high explosive. Perhaps at first sight rather obscure, it is in fact an extremely clever message, showing that the purchase of bonds, and the money generated, directly assisted the fighting at the front. In the public’s mind, bonds therefore equated to the purchase of raw materials, and the manufacture of shells, ammunitions and bombs. Such an image actually has a very direct appeal and avoids wordy explanations.

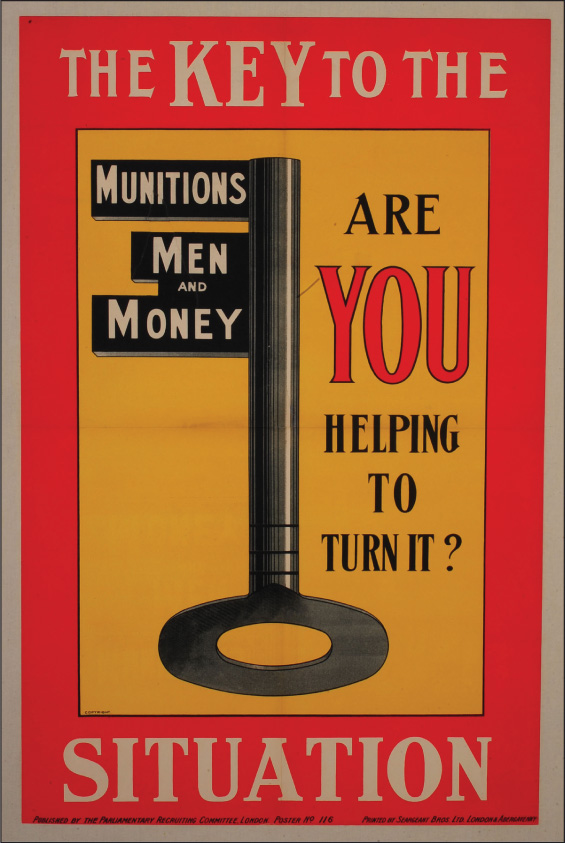

Here the key symbol is used to unlock the three main elements for an efficient wartime manufacturing economy: munitions, men and money. However, unlike the straightforward demands of a recruiting poster, this was actually a somewhat complex appeal that stressed not only the need for a suitable workforce but also for financial investment in industry, presumably by means of war bonds or savings stamps. Later posters were more focused and direct in their appeal.

This image depicts Uncle Sam, who first became a public figure when illustrated in Leslie’s Weekly in July 1916, although he had originally evolved as a character in 1835. Duplicating the famous pointing finger of the Kitchener posters, Uncle Sam was initially used as a recruitment aid, some 4 million posters being distributed in two years. The figure was painted by Dan Sayre Groesbeck (1878–1950), a self-educated Californian artist, who was to have an extraordinarily prolific output of paintings, drawings and prints. Although he is probably better remembered today for his vast panoramas of early American settler life, of greater significance was his pioneering use of story-boards for illustrating film scenes and for building up character profiles.

The pursuit of liberty was a favourite American political and social theme. The Statue of Liberty, designed by Frédéric Bartholdi, was inaugurated in October 1886 and represents Liberty enlightening the world (‘La Liberté éclairant le monde’). It was, and still is, a potent symbol of American freedom and has been represented in countless images. In this early 1917 liberty bond image, the now familiar accusatory pointing finger is allied to a rather fearsome glare to put across the message that bonds equate to freedom.

This War Savings work by Caspar Emerson (1878–1948) uses a clever visual allegory by replacing the belts of machine-gun ammunition by war savings stamps. The message from the image is unequivocal: buying stamps has a direct link with keeping the guns firing, and it is both simple and effective. This rather cartoon-like work is unusual for Emerson, who was best known for his fine dock and harbour views, and ships and whaling scenes. Less well known is that he was the great-nephew of Roald Amundsen, the polar explorer, in honour of whom he changed his name in 1943 to Amundsen.

This apocalyptic image from 1918 shows New York City harbour in flames during an attack by German battleships and bombers. It was executed by Joseph Pennell (1857–1926), an American who moved to London in the late 1880s, where he taught at the Royal College of Art and the Slade School of Art. He returned to the United States in 1917 and undertook several war poster commissions. This particular work is interesting for it is one of the first illustrations to recognise the potential of aerial bombing.

One of the classic poster images of the Great War, this shows a scout on bended knee offering to Lady Liberty her sword, on the blade of which is the scout’s motto ‘Be prepared’. It was painted by Joseph C. Leyendecker (1874–1951), who was born in Montabaur, Germany. Much of Leyendecker’s work was for the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, the most prestigious magazine of the period (the concept of Mothers’ Day came about as a result of a cover he painted in May 1914). His style is still widely copied today and this poster is still in print. The Boy Scout posters produced by Leyendecker and others helped to raise $350 million worth of donations between 1917 and 1919.

In contrast to the classical posing of the figures in the previous image, this very homely painting by Alfred Everett Smith (1863–1955) shows a doughboy father, with bullet-holed German helmet, safe in the arms of his loving family. His wife proudly holds the victory medal pinned on his chest. The implication of the poster was that there was a direct link between raising money and the speed with which the men could be brought home. The Victory Liberty Loan programme was instigated on 21 April 1919.

Even after almost a century, daylight saving is still a contentious issue. Originally conceived in 1895, it was adopted by Britain on 21 May 1916 and has remained in use ever since. Introduced not only as a means of increasing production, the use of extra daylight was estimated to have saved £8 million in electricity production during the war. In the US it was not to become law until March 1918 and it was so thoroughly disliked that after the war it was left to individual states to decide on whether or not it should be retained and the Uniform Time Act did not come into force until 1966.

‘Charity for the devastated Somme.’ This charity was set up in 1917 when the Germans retreated to the Hindenburg Line and civilians immediately returned to their home villages. The methodically felled trees in front of Albert’s famous leaning Virgin, the lunar landscapes that need sowing and the absence of any but temporary wood lodgings only hint at the difficulties. By listing the destroyed villages and their populations, the charity encouraged donations in cash and in kind. The example of the village of Maurepas is striking: the first donations to arrive here after the war were a bicycle and a cow. For months the inhabitants had to live in abandoned bunkers and crumbling cellars. A cow provided vital milk, butter and cheese, while a bicycle allowed access to nearby markets.

‘The loan of liberty.’ (The flags, from left to right, read ‘War until victory’; ‘Victory over the enemy’; ‘Do not let the enemy take the liberty you have conquered’; and ‘Liberty’.) With the first Russian Revolution in February 1917, the question of pursuing or stopping the war became central. The provisional government led by Kerensky was determined to honour its alliances. This poster therefore shows a perfectly organised army in harmony with the people. The figure of the soldier, in his protective stance, defends the nation’s newly earned freedom. However, military set-backs and the November Revolution would lead to a change of policy: Lenin and the Bolsheviks would sue for a separate peace ultimately signed in Brest-Litovsk in 1918.

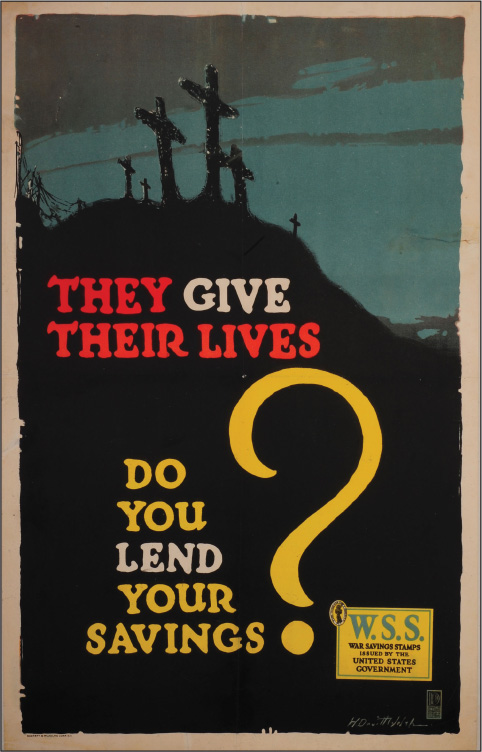

This very stark poster by H. Devitt Welsh (1888–1942) is of a very different form from the many heroic types that were still being produced. It is no small coincidence that the image is strongly representative of the three crosses of the Calvary, and the message is one of personal sacrifice for a greater cause. It was issued by the Committee on Public Information, Division of Pictorial Publicity, in 1917.

This gloriously patriotic piece is in direct contrast to the previous illustration. It was created by Sidney Riesenberg (1885–1932), a Chicagoborn illustrator and painter who moved to New York, where he achieved considerable success producing covers and illustrations for popular magazines of the day, such as Harper’s, Collier’s and the Saturday Evening Post. Like Dan Groesbeck, Riesenberg is best remembered today for his mainly western-themed paintings, and some of his original works have recently fetched record prices. His two most famous posters were this one and the much-reproduced ‘Remember the Flag of Liberty’.

This charming poster uses a rather wry take on the ‘over the top’ message which is quite different from other interpretations. The artist was the wonderfully named Maginel Wright Enright Barney (1881–1966), who was the sister of the famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright. She became a very well-known children’s book illustrator, as well as a prolific magazine artist. The charging vegetables are a clever substitute for the attacking soldiers usually found in wartime posters, and were aimed at encouraging more people to grow their own fruit and vegetables. This poster was not released until 1919, after the war, when food was still in short supply.

Finding sufficient raw materials to keep war production going was difficult, particularly as the U-boat campaign began to take a heavy toll on Allied shipping. This unusual and particularly striking image depicts a British soldier calling to the viewers to give as much scrap metal as they could. It is unusual in having the name and contact details of a metal dealer, Brahams, on the poster. Most information posters were more general in content, and whether this was sponsored by Brahams is unknown.

‘National loan 1918. To give us back all our sweet land of France.’ This scene simultaneously reflects a pastoral tradition and a leitmotiv of military painting. France was still a rural nation during the Great War. In fact, it was not until 1929 that the urban population topped the rural one. The harvest was therefore an explicit sign of plenty, and these women, replacing the male farmers, links this imagery to the war context. The troops in the sky, led by the French Marianne allegory, echo the pictorial symbols of historical and military paintings recalling the Napoleonic era.

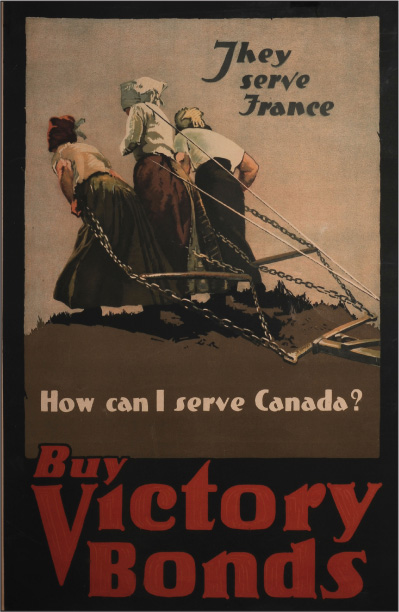

Canada did not produce as many posters during the war as other Allied countries, but those that were issued tended to be of high quality and used imagery very cleverly. This one, reproducing in art form the famous photograph by the French official artist Tournassoud, shows three toiling French fieldworkers. It is a finely executed and thought-provoking image showing that ordinary life had to continue in the absence of both men and draught-horses. The image of women pulling a plough would have been quite shocking to the generation of the Great War, with its subtle message that in order to help win the war, the women of France were prepared to be beasts of burden.

‘For the last quarter of an hour ... Help me. Subscriptions to the National Loan can be taken at the National Bank of Credit.’ Sem (also known as Georges Goursat) had made a name for himself, principally among socialites, as a portraitist. For this 1918 war loan poster, he depicts General Foch reviewing his troops going off to battle. The direct appeal of the Commander-in-Chief of the Allied armies is almost a pressing order. The artist uses the fact that military leaders were then revered authorities. Their prewar prestige grew with the conflict, often overshadowing political leaders in patriotic productions (such as tableware, postcards and statuettes). The figure of Foch rapidly became omnipresent.

‘For triumph. Subscribe to the national loan. Subscriptions can be made in Paris and the provinces. National bank of credit.’ Many artists used France’s long military history to make the Poilu the last link in a glorious tradition. References to Napoleonic soldiers are extremely frequent. In this case, the men of the Great War are literally descendants of revolutionary soldiers: the Arch of Triumph pillar is illustrated with Rude’s sculpture of French Revolutionary volunteers. The artist Sem anticipates the renewed triumph of French forces over aggressive foes and represents the men parading past the Arch of Triumph.