The soldier was the central figure of most war posters. This representation was never static and evolved over the course of the war. Initial posters echoed the enthusiastic images propagated by the press or in cheap media such as postcards. However, with time and ever-mounting casualties, a more subtle image of the soldier started to appear: certain artists were also soldiers and had experienced at first hand the discrepancy between the war they had imagined and the reality of combat. A more restrained imagery began to appear, centred on the courage needed to hold the line without necessarily attacking at all costs. The question of the wounded also raised the issue of what could be shown and what might be considered demoralising or too gruesome. New representations appeared without completely erasing the former ones. With victory in sight, there was a return in the Allied countries to the earlier images, renewing the dynamic, even aggressive, vision of the early war period.

Nevertheless, some elements were constant. The soldier was always a reassuring figure; he represented virility and was regularly portrayed as being admired by women. More than an individual, the soldier stood for the whole country. He was closely associated with the earth element, not just because he fought in the trenches but because, in the still predominantly agricultural societies of the time, this evoked the eternal values of land and country. It is striking how opposing countries could use almost identical imagery: the soldier as a symbol of a united nation (which had put aside any political or social differences) was therefore also an allegory of each country’s long glorious history.

For this reason, traditional imagery of mythical figures and allegories flourished. Medieval knights and Greek warriors were commonly represented, a phenomenon that was not without some nostalgia. By using such models one could become part of an epic tale that absorbed fear and suffering into a greater meaning. A sub-category of these heraldic elements is the use of animals to represent the country, and at the same time values such as courage and force.

Of course, the reality of a modern war did not escape the public or poster artists. The lone warrior became an increasingly mechanised and even collective entity. Technological superiority was used as shorthand for certain victory in the near future. Although the prewar arms race had seen the development of constantly bigger armoured battleships, these Dreadnoughts did not have a determining impact, and submarines became the main naval weapon represented in posters. The Great War was also exceptional in the sense that new weapons were created during the conflict itself: the massive dimensions of the tank assured its maximum visual impact and therefore great pictorial success.

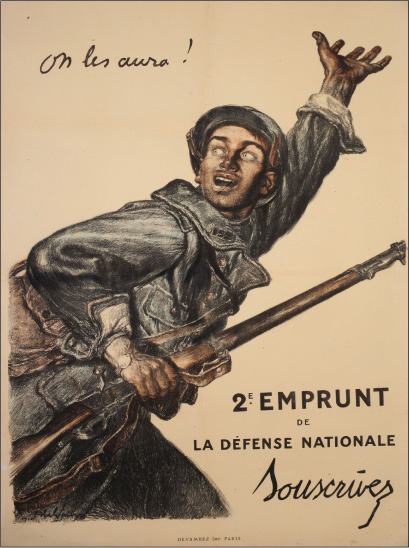

‘We’ll get them! 2nd national defence loan. Subscribe.’ This is probably the most famous French poster and some 200,000 copies graced the nation’s walls. Its force resides in the soldier’s gesture imitating Rude’s sculpture on the Arch of Triumph in Paris. Abel Faivre transposes this reference to national history on to his model, Jean-Baptiste Decobecq, a private from the occupied city of Valenciennes, and thus a symbol of the country in peril. The first draft portrayed a furious face but the final version insisted on the enthusiasm that overcomes everything. The words ‘On les aura’ were also used in General Petain’s famous order dated 10 April 1916 during the battle of Verdun.

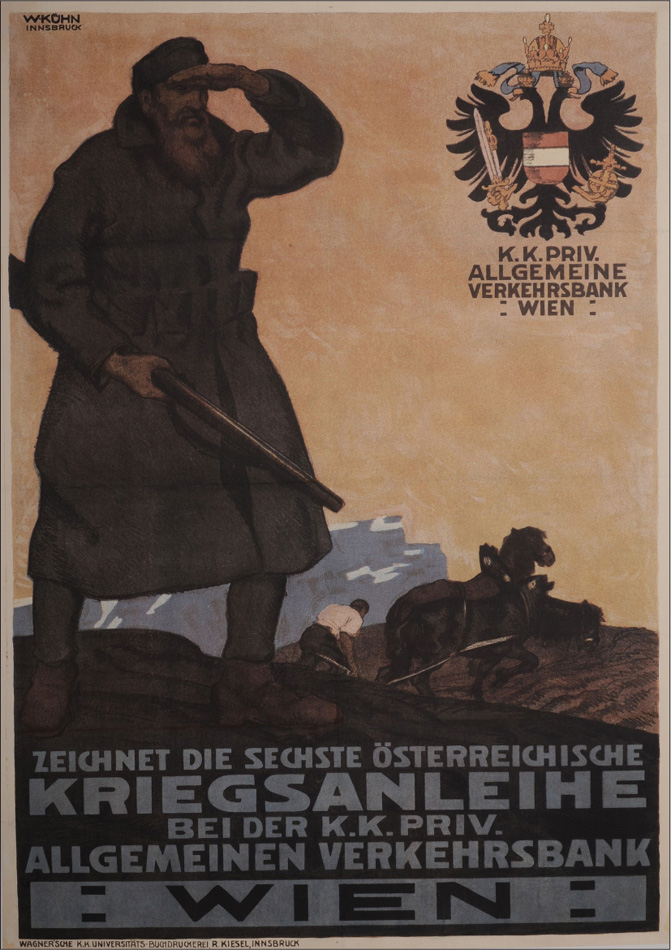

‘Subscribe to the sixth Austrian war loan by the Royal and Imperial Private General Commerce Bank. Vienna.’ This Austrian poster portrays an important component of masculine identity: men were responsible for the security of the community whatever their age. The bearded, and therefore virile, man has not hesitated to take up arms to fend off the (unseen) enemy. In the multicultural Austria-Hungary, such simple illustrations could reach out to all its members.

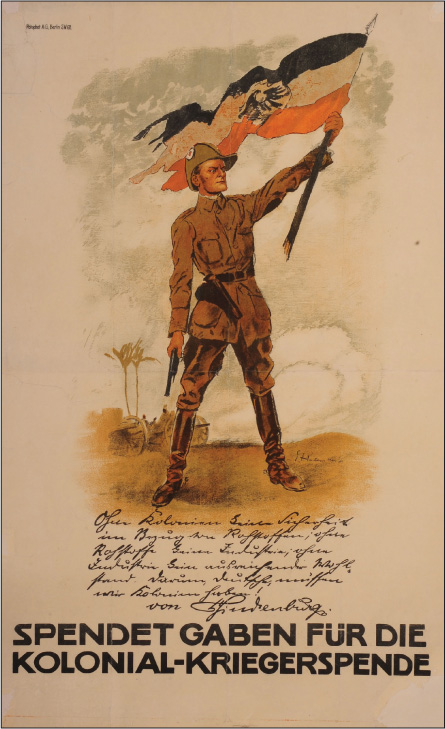

‘Give your donations to the Colonial Warrior Charity.’ Two million Africans fought in or worked for the war. Several hundred thousand fought in Europe as well as in Africa, where most German colonies were quickly overrun by superior Allied troops backed by a powerful navy. However, Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck led a guerrilla war in today’s Tanzania until 25 November 1918. The figure of the German colonial soldier, here seen proudly waving the Imperial flag, became a symbol of obstinate resistance. The contribution of Africans (on all sides) raised lasting questions of rights and self-determination in the colonies.

‘Help us win! Subscribe to the war loan.’ Erler’s work for the sixth war loan in 1917 is the first German representation of the soldier at the front. It was massively distributed and contributed to creating a new image of the modern soldier. The steel helmet would become the symbol of the war which literally forged a new iron fighter: Ernst Jünger in Storm of Steel describes how the line of the new helmet hardened the look of his men as they entered the inferno of the Somme. This imagery would be systematically used when role-model figures on posters became more generalised in the 1930s and 1940s.

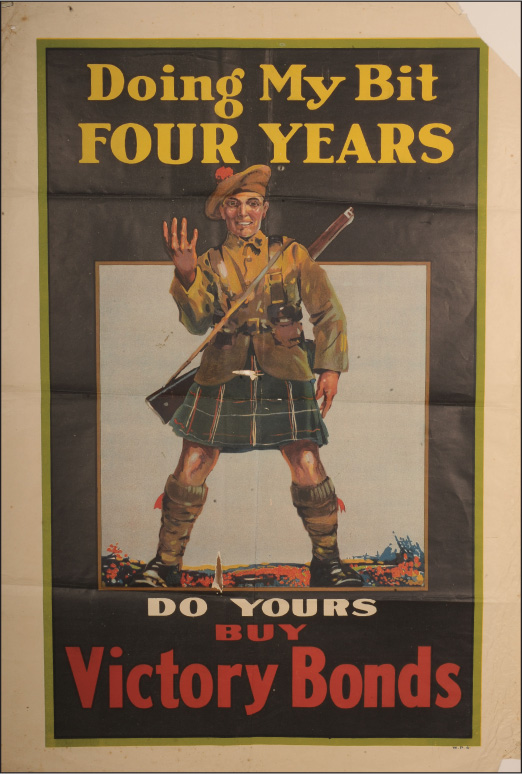

This somewhat jollier painting depicts a Canadian Scottish soldier exhorting the public to help the war effort by buying bonds. Canadians, particularly those of Scots and Irish descent, were immensely proud of their ancestral roots, and this is a direct appeal at those who would have identified with the kilted figure. Canada had been in the war since 1914, and by the armistice had paid a high price for her involvement, losing 67,000 killed and 150,000 wounded.

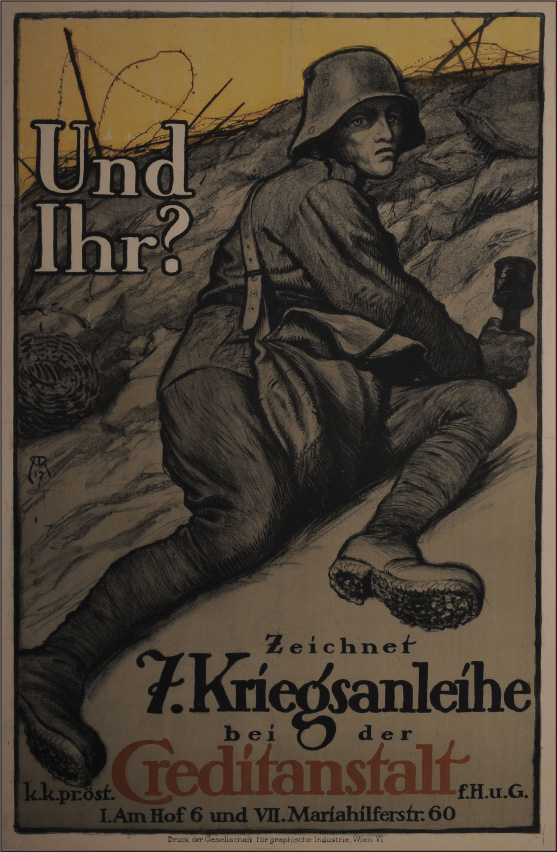

‘And you? Subscribe to the seventh war loan at the Credit Centre.’ This Austro-Hungarian poster represents a typical stormtrooper. The hand grenade was more practical for fighting in the trenches and for neutralising dug-outs. Stormtroopers were lightly equipped but heavily armed to allow rapid movement. The initiative permitted to them on the battlefield was a radical departure from the rigid adherence to orders of the middle of the war. Introduced as a way of countering the Allies’ growing technological superiority, this fighting technique re-established the individual’s will as a decisive element of victory. The figure of the warrior was central to war propaganda and to Remembrance.

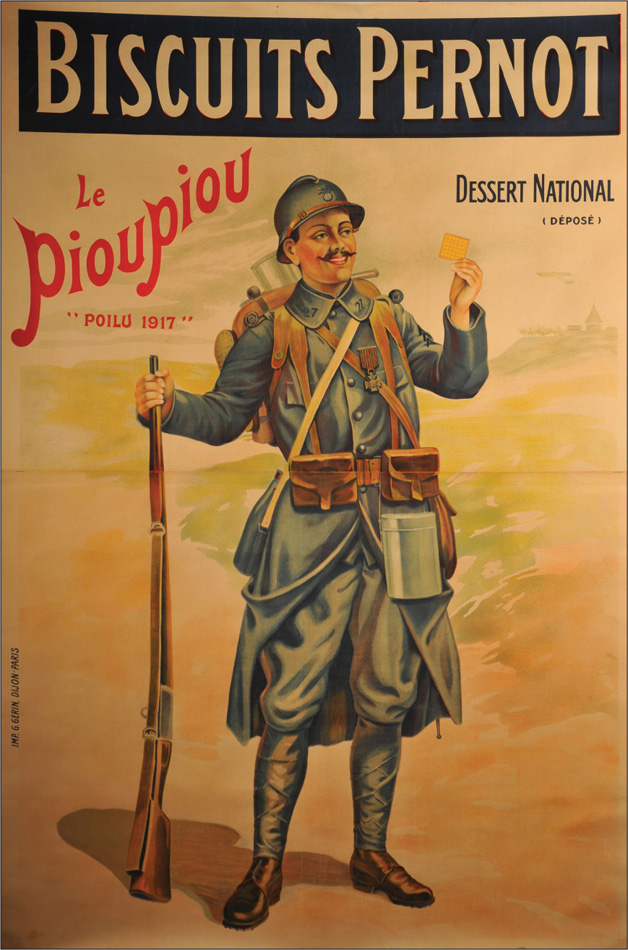

‘Pernot biscuits. National dessert. The piou piou “Poilu 1917”.’ (Piou piou was an affectionate nickname for the French soldier in 1914, while poilu was a nickname extolling the soldier’s virility.) The typical French soldier is represented here, wearing the blue uniform and carrying the standard equipment. The Croix de Guerre (the French equivalent of a Mention in Dispatches) and the virile moustache contribute to a highly positive image. Representing a soldier quickly became an excellent advertisement tactic for a great variety of products.

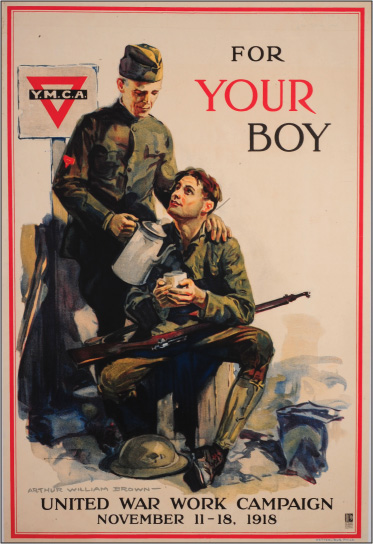

The YMCA (Young Men’s Christian Association) was formed in 1856 and provided vital aid to soldiers during the American Civil War. In 1917, when the United States joined the war, it fielded some 35,000 volunteer workers to provide ‘spiritual and social support’ for the troops, and they provided 90 per cent of all welfare for the US Expeditionary Force in France, operating from twenty-six bases; it has been calculated that some 2 million US soldiers made use of their services. During 1917–1918 the YMCA lost six men and two women as a result of enemy action and earned 319 decorations. What is less well known is that the YMCA also provided aid and comfort to prisoners held in Allied camps.

‘Exhibition of the Allies organised for the profit of the exhibitors and the artists’ fraternity.’ The ‘mise en abyme’ or self-reflection of this poster was not a novelty of the war. Many posters for films or plays had spectators represented on them. In this case, it reflects the military power of France’s numerous Allies. In this case, having different nationalities present was also in part a way to invite larger audiences: the cultural scene had been hard-hit by the war. Theatres did not reopen until 1915 and artists were regularly harassed for not being at the front.

‘Every class smokes the Riz la Croix.’ This advertisement for cigarette paper can be dated to 1917. With conscription, every young inductee would be given as his enlistment-class number the year he turned twenty. These classes appear in the smoke. The old Territorial would have been out of the army if it were not for the war, and 19-year-old soldiers were only called up in advance to compensate for the war’s losses. Simultaneously, propaganda encouraged pro-children policies: babies were drawn ready to fight. Despite the spring mutinies, the French population could not imagine not fighting on until victory.

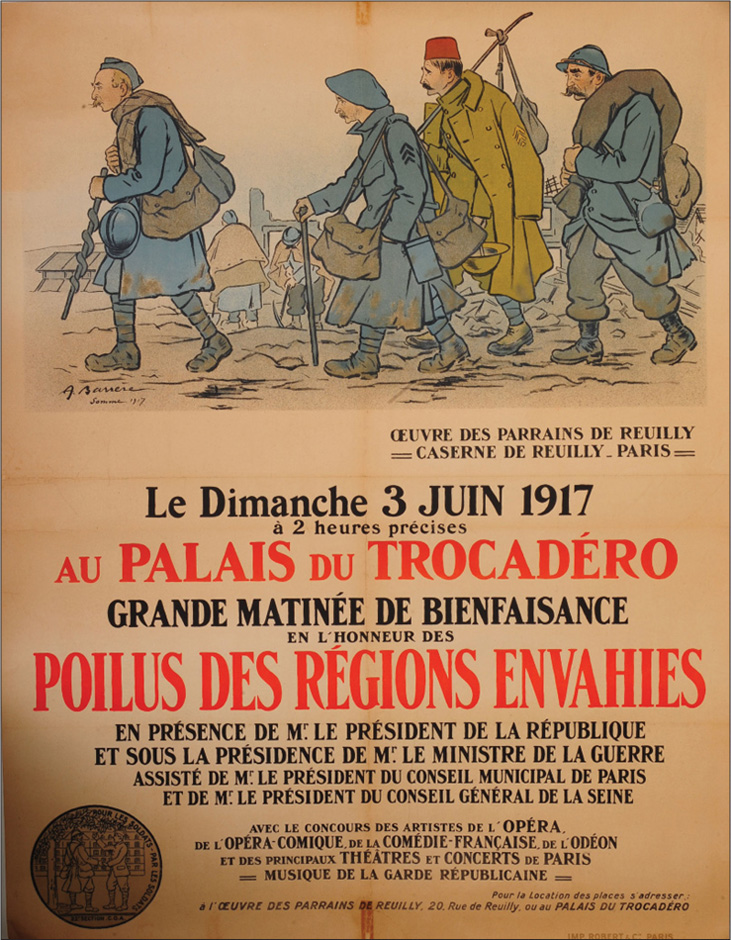

‘Sunday 3 June 1917 at 2 o’clock sharp at the Trocadero Palace Grand Charity matinée in honour of the soldiers of the invaded regions.’ Adrian Barrère was an official French war artist sent to the front to show the work of the Medical Corps, and his work is more realistic than most. He depicted everyday life scenes of soldiers, be they infantrymen, chasseurs or colonial troops. The stripes on the two central characters’ arms indicate that each has been fighting for over two years. The artist also includes details such as the hand-carved cane on the left. The tired looks nevertheless do not question the determination of these men.

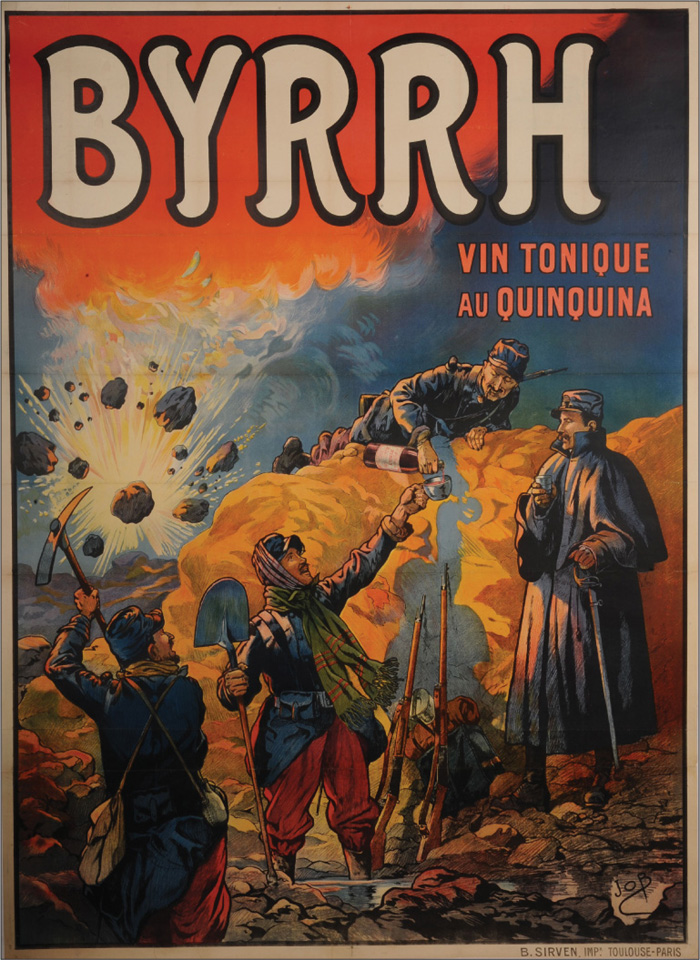

‘Byrrh. Tonic wine with cinchona.’ Jacques Onfroy de Bréville, better known as Job, had been in the French Army before becoming an artist, caricaturist and illustrator for children’s books. He was especially gifted at drawing French history and uniforms. Thus many equipment details are painstakingly reproduced. However, the unrealistic position of the soldier outside the trench, despite being designed to better fill the picture, would have annoyed front-line soldiers. Even years after the war, veterans would bristle at anything considered not exactly correct.

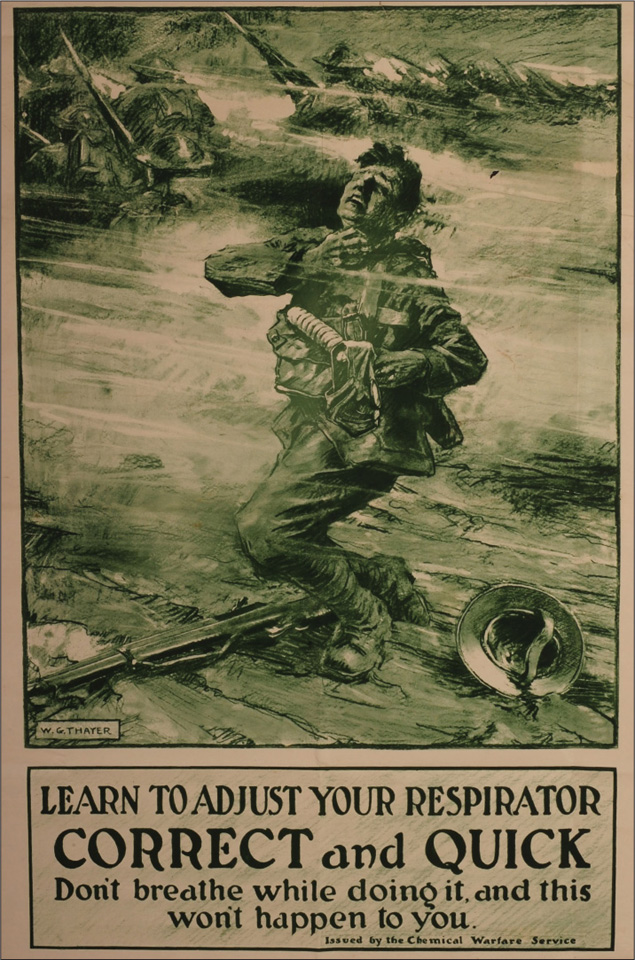

Few posters survive that were aimed at the fighting soldier, but this one, put up in large numbers in American training camps in France and Flanders, is self-explanatory. It was drawn by Lieutenant W.G. Thayer of the US Army’s Gas Defence Division, which was established in June 1918, and shows the potential fate of failing to wear a gas mask. Gas attack was a constant threat during the war and such messages were taken seriously as the result of gas inhalation was terrible.

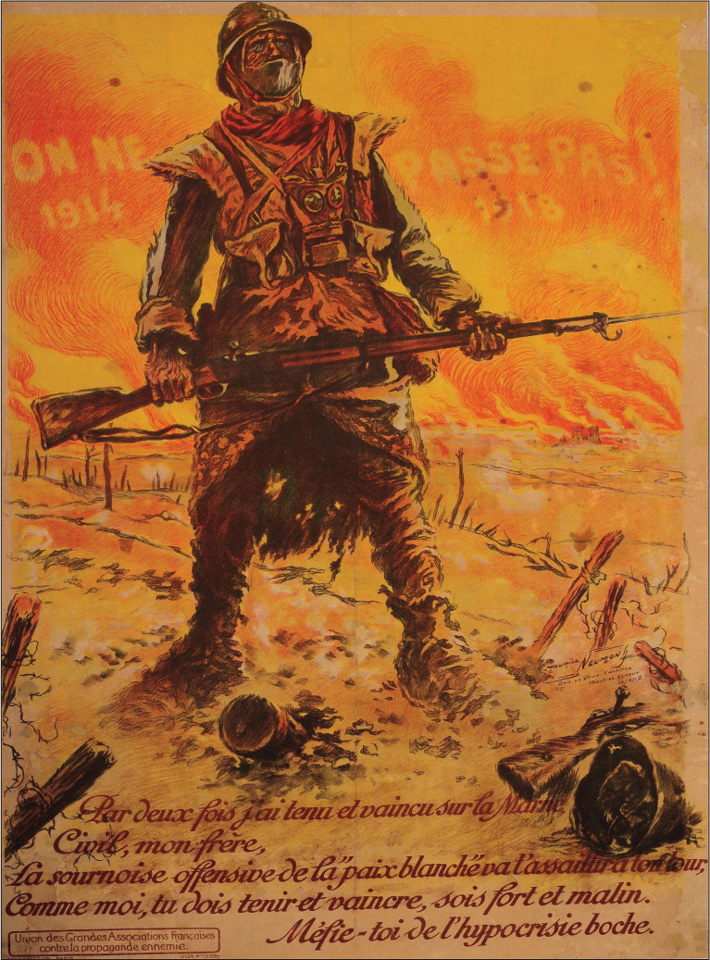

‘Twice, I have held and won on the Marne. Civilian, my brother, the tricky offensive of “Peace without victory” will also attack you. Like me, you must hold and win, be strong and clever. Beware the Boche hypocrisy.’ Years of bloody stalemate had made enthusiastic messages seem out of touch. With a French average death-toll of more than 850 men a day, courage was no longer the ability to take the offensive but became also a stubborn, stoic resistance symbolised by Verdun and the Marne. The haggard soldier barring the way against the enemy would become in the postwar years a much-used symbol in France.

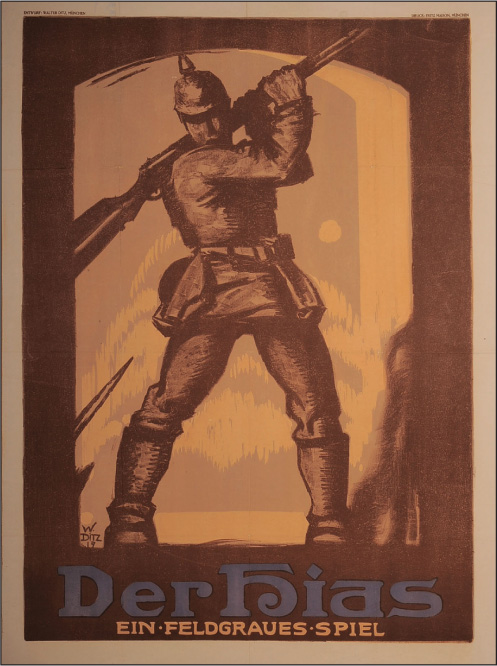

‘The Hias. A field-grey theatre play.’ The Hias (a derogatory abbreviation of Matthias) was a Bavarian patriotic play produced by soldiers and officers. It glorified comradeship and war as an adventure through the main character of the dumb batman. Whereas another poster of the play shows a German attack, this poster has the Hias in question positioned for a last stand. Alone against the (unseen) enemy symbolised by the bayonet, using his empty rifle as a club or a sword, he resembles a heroic defender in the wall’s breach. Such an image would have been immediately understandable by soldiers and civilians alike: the Germans were defending their homeland.

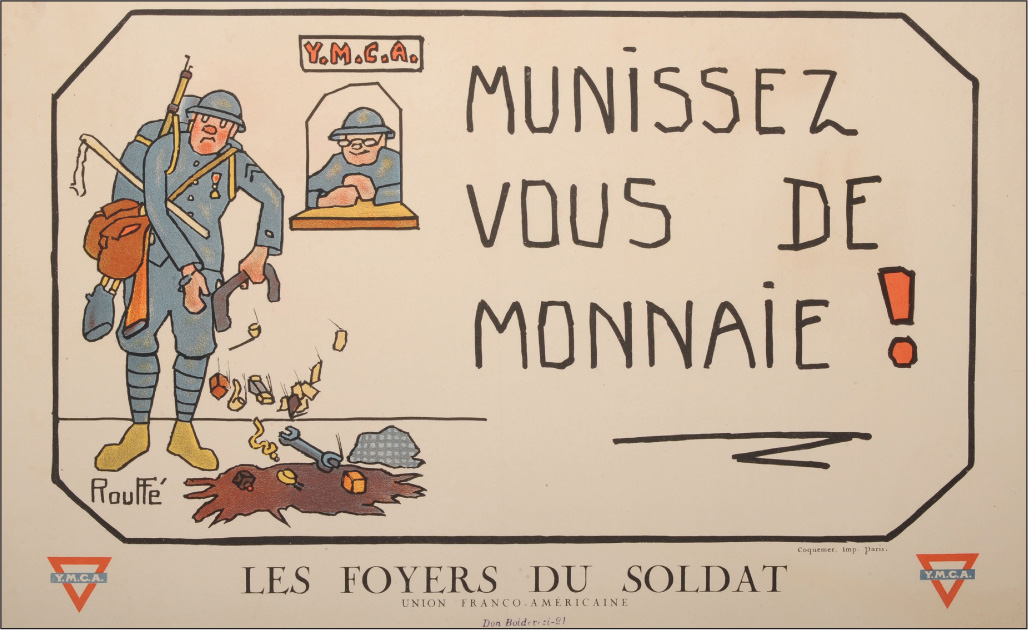

‘Please give exact change.’ This poster belongs to a series produced by Rouffé, whose posters have a cartoon touch to them as the artist was known for his humorous works in the illustrated newspaper La Baïonnette (‘The Bayonet’). These posters were designed to influence the conduct of resting soldiers at YMCA homes. It was probably more realistic to ask for the resting troops’ cooperation through a light-hearted message than to issue yet another formal order. By the end of the war many non-strategic interactions between the hierarchy and the men had been made less strict.

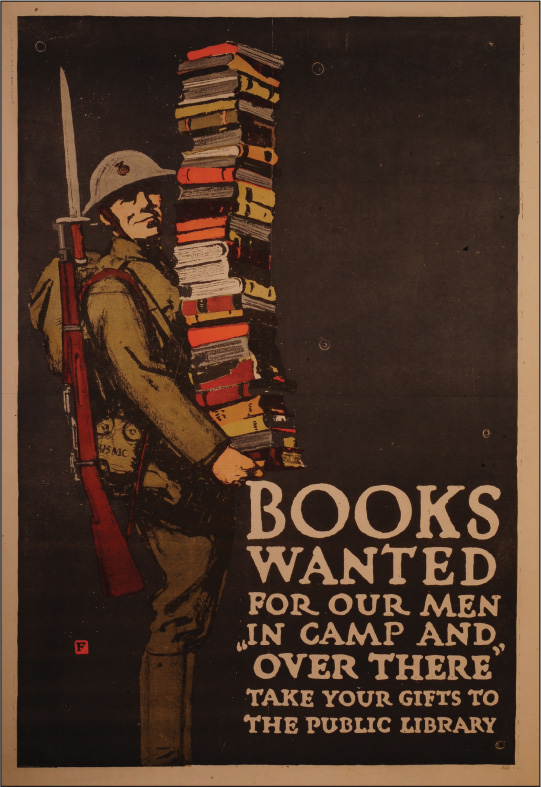

As this grinning soldier makes clear, soldiers were not only fighters. The American Army deemed books so important for morale that they had official travelling libraries that could be carried as a backpack by an individual soldier. Libraries were set up in camps, hospitals, prisoner of war camps and even on board ships. Universities were set up in France to enable the soldiers to learn a trade in preparation for returning to civilian life. According to the American Library Association, over 7 million books were given out.

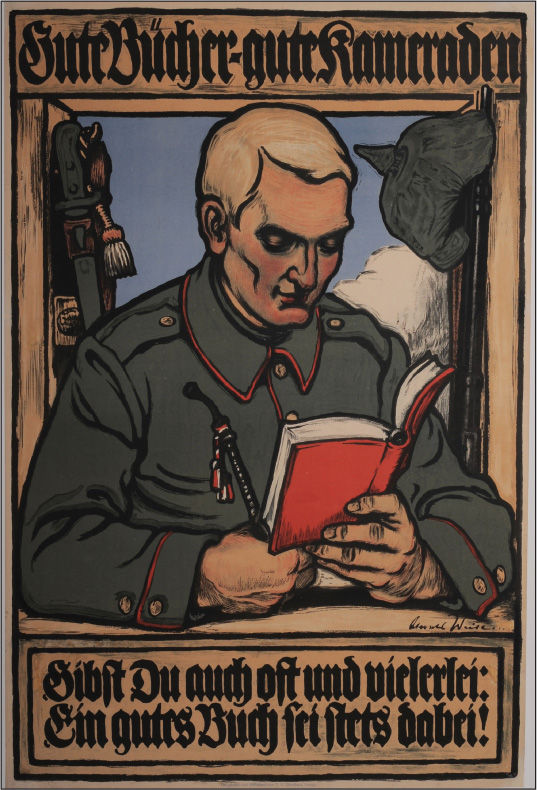

‘Good books, good comrades. You, too, give often and of all kinds: a good book is always free here!’ The troops often had long periods of waiting, and books provided a way of keeping these men calm and healthily occupied, as shown here. It was also a way of mentally escaping from the war, of reconnecting with prewar cultural practices or simply of understanding the ongoing war: in Germany alone well over 10,000 essays were written about the war as it was taking place. Among other contributions, 250,000 books were given by the German Librarian Association and 100,000 other books by the Association for Promoting Popular Culture to hospitals.

‘Cologne August September 1916. Exhibition for war welfare. Aid for war wounded. Apprenticeships and vocational training.’ The soldiers’ sacrifice was central to the mobilisation of the home front. Images designed to cause feelings of guilt would cut short any debate: they dramatised the hardships of the front in order to minimise the civilians’ conditions. The sling, the crutch and the bandages were the typical representations of the wounded that eliminated cruder and potentially unbearable visions of war. The rhetoric of the unique, incomparable experience of the soldiers would continue after the war: many ideologies, not least the Italian Fascist and German Nazi visions, advocated a militarised country.

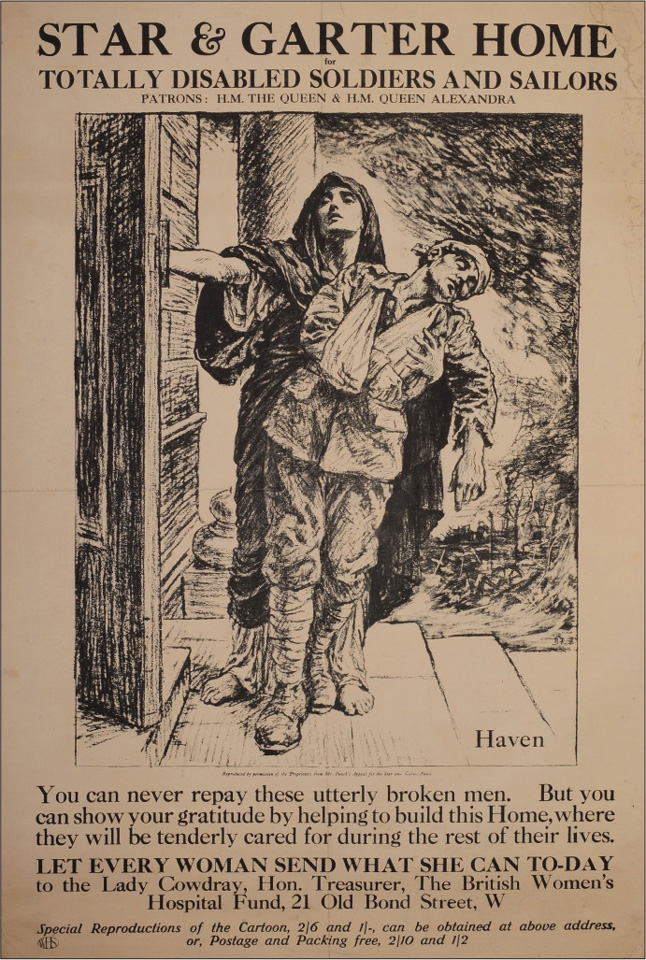

Many historians regard the true cost of the war not simply in terms of the dead, but also the wounded – the physically maimed and mentally damaged who required constant care for the rest of their lives. Queen Mary was so concerned about available care for the badly wounded that in 1915 the old Star & Garter Hotel in Richmond, Surrey, was purchased and converted into a Home with disabled access; the first sixty-five men were admitted in 1916. Their average age was 22. Britain alone had over 1.6 million men wounded, of whom some half a million were never able to lead normal or productive lives again. A purpose-built home replaced the old hotel in 1924.

‘The French artistic toy drawn by the artist Job. Built by wounded soldiers in Bordeaux.’ Mrs Prom and other influential women started ‘the French artistic toy’. The artist Job drew the models, which could be copied in beech wood by war invalids in reeducation facilities. The toys, with mostly civilian and animal themes, were first displayed in 1916 and would continue to be sold until 1935. This kind of production was also done by the occupied population in Belgium and, in a more warlike fashion, by British wounded and Belgian refugees.

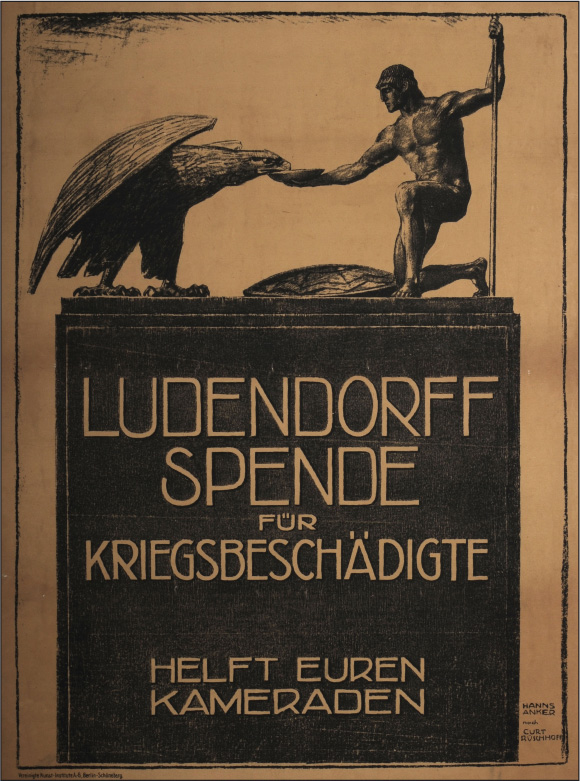

‘The Ludendorff donation for war wounded.’ Ludwig Hohlwein transformed the art of posters. As early as 1906, in his first posters, he had parted with the typical crayon drawings to adopt big juxtaposed colour patches that created shades and stark contrasts. The result was at once one of great simplicity and powerful realism. His prolific output helped make him an essential figure in German art and contributed to the image of the determined – even when wounded – soldier. In the Second World War Hohlwein was an active Nazi, and his pictures of strong, iron-clad soldiers continued to serve German propaganda.

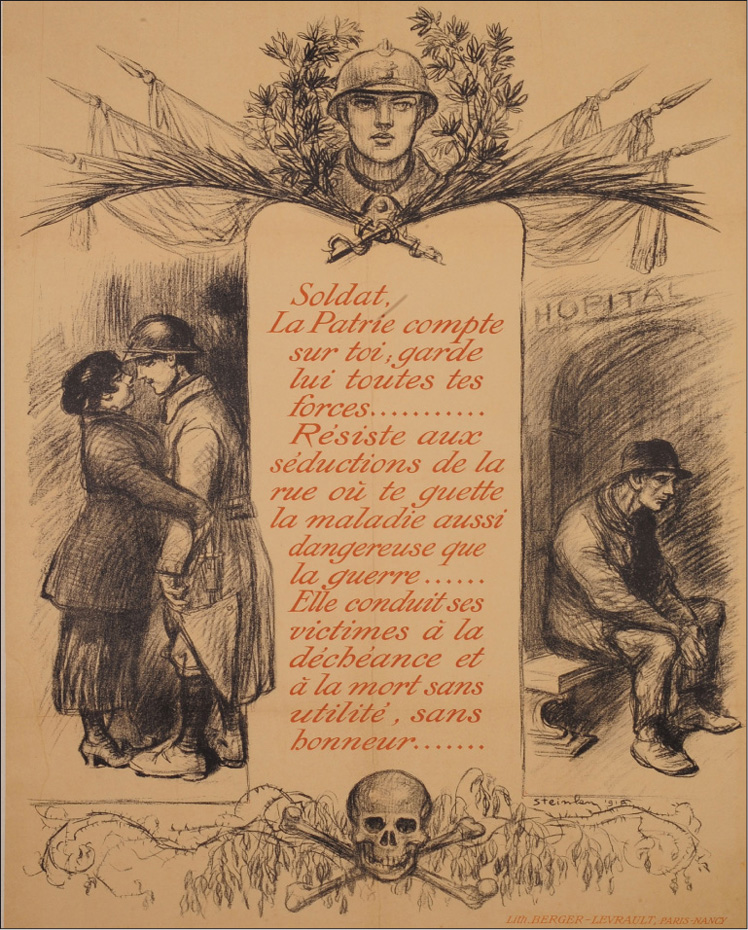

‘Soldier. The country is counting on you. Keep all your energy for her. Resist temptations on the street where sickness awaits you, as dangerous as war … It leads its victims to decline and death without any use and any honour.’ Broaching such a subject was delicate. Soldiers were supposed to be paragons of virtue, embodying the noblest values of the country. Nevertheless, this vision did not prevent, for example, 50,000 Americans from being on sick leave due to sexually transmitted diseases at any given time during the war. This reality increased manpower problems. To counter this, the message here is based on moral considerations and strongly condemns any weakness as a lack of commitment to the war effort.

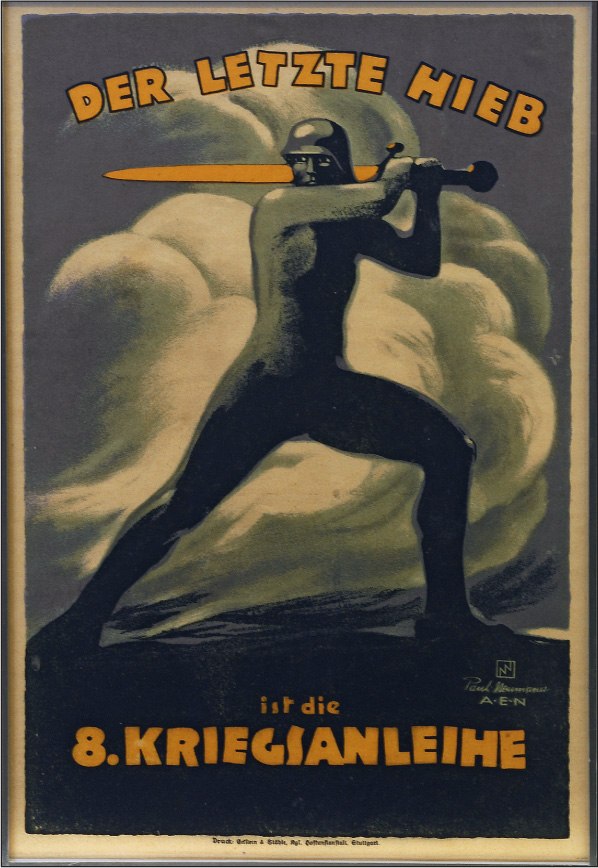

‘The last blow is the 8th war loan.’ German art was heavily influenced by ancient Greek and Roman culture, as well as by medieval imagery. Since the end of the nineteenth century nudity had again become a symbol of superhuman qualities. The strength and beauty of the body are central to this composition as the timeless soldier is recognisable only by his steel helmet. This classical representation places the warrior in the lineage of gods and heroes. Such idealised posters helped to minimise the massive death toll of the Great War and the growing possibility of defeat for Germany.

‘War loan 5.5%. By giving their blood for the country, our courageous soldiers are doing their saintly duty. Do yours too, subscribe to the loan.’ By the turn of the century the medieval knight had become a unifying figure for the German nation and its war-preparedness, embodying the military and aristocratic traditions that had been upset by the economic transformations of the industrial age. Imagery depicting St George, Siegfried and other knights battling dragons was therefore widely used in most warring nations. The iconic past became a way of explaining the modern, technological war in simple antagonistic terms. The hero fought Evil, often in a dehumanised form.

‘And you? Subscribe to war loans.’ In what was essentially a war of anonymous masses pitched against one another, aviators quickly became the modern equivalent of the medieval knight jousting alone. The fighting in the skies was described as duels, where daring and skill carried the day. The best pilots qualified after five victories for the prestigious title of ‘ace’. Among the most famous were the German Manfred von Richthofen, better known as the Red Baron, who scored eighty victories, the British Edward Mannock (seventy-three) and the Frenchman René Fonck (seventy-five). The press eagerly recounted their exploits, turning them into heroes who became role-models.

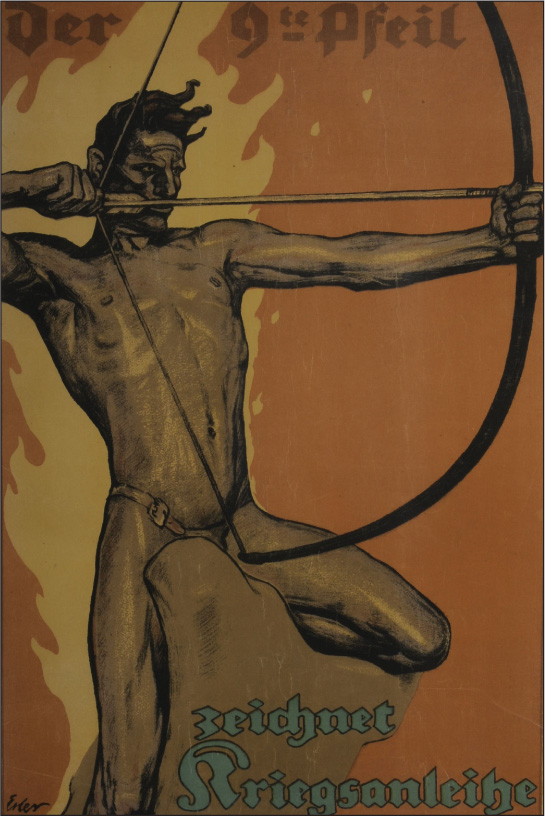

‘The 9th arrow. Subscribe to the war loan.’ During the war the bowman/archer and his weapon were a recurring theme in war posters because it gave a specific and clear goal and enabled the artist to show an enemy that was already hard hit. Even before Goethe’s and Hegel’s writings, heroic nudity was a classical element of the idealised fighter. Its epic dimension negated total industrial war and created an aura of invincibility that was disconnected from the realities of the field. Particularly in Germany, this representation foreshadowed the imagery of later war monuments.

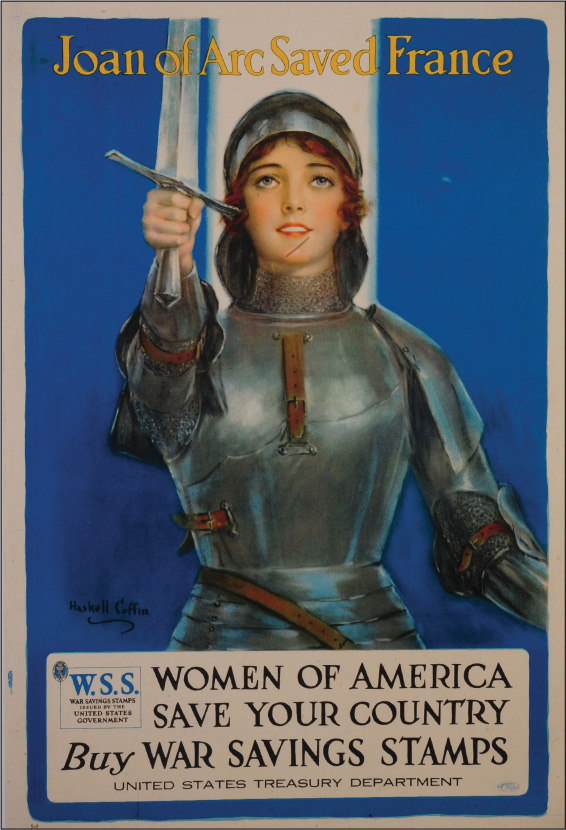

This American poster has a somewhat different theme, relating directly to perhaps the most famous of French historical figures, Joan of Arc, and aimed directly at women, who are urged to buy savings stamps, a low-cost form of bonds. The image is a very finely executed one by William Haskell Coffin (1878–1941), who was well known for his very popular magazine cover paintings of beautiful women. His wife, whom he worshipped, is believed to have posed for the Joan of Arc portrait. Sadly, for it was a great loss to the art world, he committed suicide after his divorce in 1940.

‘National loan 1920. Loan your money to France so that it may grow in the shining light of peace. One can subscribe without fee at the national discount counter and in all its agencies.’ The allegorical Marianne figure, crowned with the laurel wreath of victory, has here only a cockade to identify her. The Model 1886 bayonet, symbol of the fighting spirit of 1914, has been turned into a peaceful garden stake. The importance of the land in a predominantly agricultural society is therefore very present but the wooden crosses in the background serve as a reminder of the sacrifice of the men.

‘National Commercial Bank of Paris. Badon-Pascal Pommier and Company. National loan 1920. 6%. To subscribe is to save for the future.’ The Gallic rooster had been the unofficial symbol of France since the Middle Ages. During the Great War the cockerel was both a catholic symbol of hope for the return of Christ, and a Republican symbol of the Gauls considered to be the first Frenchmen. The singing cockerel was widely used in 1914 and 1915 to signify that victory was imminent and again, for obvious reasons, from 1918 onwards.

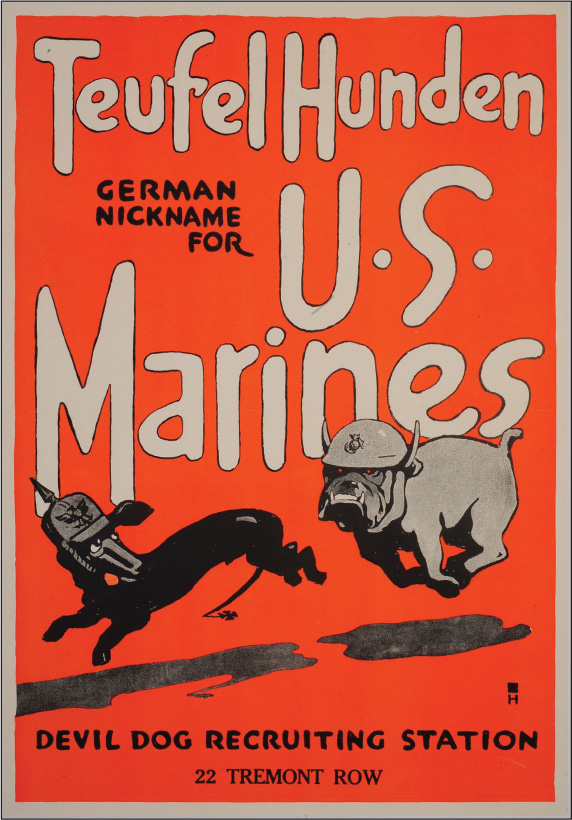

‘Teufel Hunden.’ A cartoon poster representing the German Army as a dachshund but, unusually, the US Marines as a bulldog (an image more normally associated with Britain). Marine legend has it that after the intense fighting for Belleau Woods in 1918 the marines were known by German soldiers as ‘Devil dogs’, but as with many wartime myths there is no factual evidence to back this up. In fact, the term was used by at least two newspapers prior to the battle and no evidence from German sources has ever been found to substantiate this claim.

‘Ludendorff fund for war victims. Help your comrades!’ The eagle had been the heraldic animal of German kings since the fourteenth century and symbolised the German Empire. It is here being fed by a Greek soldier. The classic aesthetic of masculine beauty transcends the reality of a modern war, making a highly positive self-image for the world war soldier: they are seen not only as fighting on the borders but as actively helping the very heart of the nation. The use of images from the much valued mythologised past reveals the trend in mainstream fine arts back to traditional standards that were readily understandable, yet gave a greater meaning to the participants of the war.

Unlike the German eagle or French cockerel, animals do not often feature in British posters, but this one by Arthur Wardle (1860–1949) is a fine example of the use of a professional artist who specialised in animal painting. It shows a pride of lions and is specifically aimed at the recruitment of dominion soldiers from the ‘Overseas States’. Wardle was to become the most significant painter of dogs in the twentieth century.

This rather pleasing poster of a small dog begging for donations for the International Red Cross was painted by American artist Richard Fayerweather Babcock (1887–1954) and was one of several he undertook for it. The International Red Cross Organisation was founded in Geneva by Jean-Henri Dunant in 1863 to provide humanitarian aid without discrimination. Hundreds of men joined to act as ambulance drivers and medical staff, and they suffered a higher proportion of killed and wounded than any other volunteer unit during the war. Some measure of the level of support the Red Cross provided to the warring factions is that it was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1917, before the war had even ended.

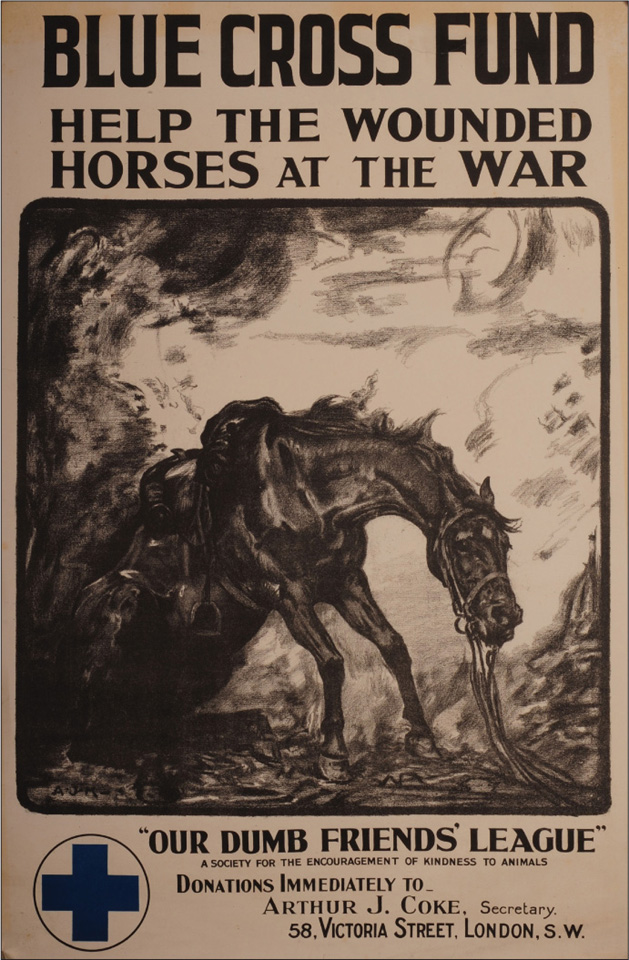

The armies of the Great War were still largely horse-drawn but the plight of the animals went largely unrecorded. Some idea of the scale of the carnage can be gleaned from the fact that over 8 million horses and mules on all sides were killed during the war, and over 2.5 million were wounded and received treatment. Britain employed over a million, but after the war only 60,000 were returned home. The Blue Cross was founded in 1897 ‘for the encouragement of kindness to animals’ and the charity still works tirelessly to alleviate suffering to any animal.

‘War loan 5.5%. Forthright participation in the loan is everyone’s duty.’ Controlling the seas was a major issue for the Russians. Imports soared with the war, forcing Russia to depend on its allies for a great deal of wartime production. Archangel port near the Arctic Circle could only be used during the warmer months, and in the south the Turks held the Dardanelles Straits giving access to the Mediterranean. The Pacific ports were soon saturated. Depicting a determined naval gun crew was therefore not only a matter of pride but also a way of showing a matter of vital importance: this gave the call for war loan subscriptions a real sense of urgency.

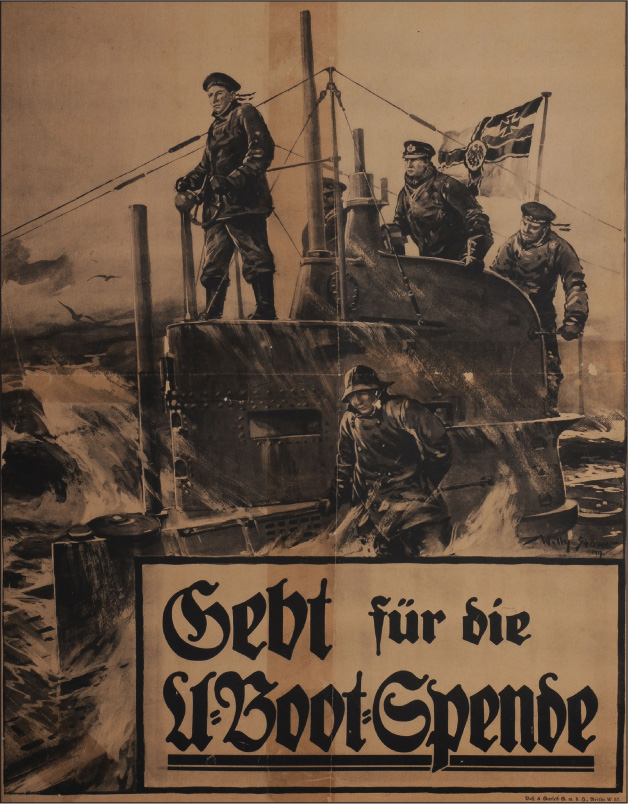

‘Give for the submarine fund.’ Artists did not always draw specifically for posters. One of the Kaiser’s favourite naval artists, Willy Stöwer, painted submariners as heroic adventurers in a wild environment. He turned one of his works into this 1917 poster by simply adding the text. He also sold his works printed in postcard format and gave the profit to help submariners. Adapting images to a variety of sizes and media was commonplace during the war. Famous posters, postcards or drawings could then even be copied by soldiers for their trench art.

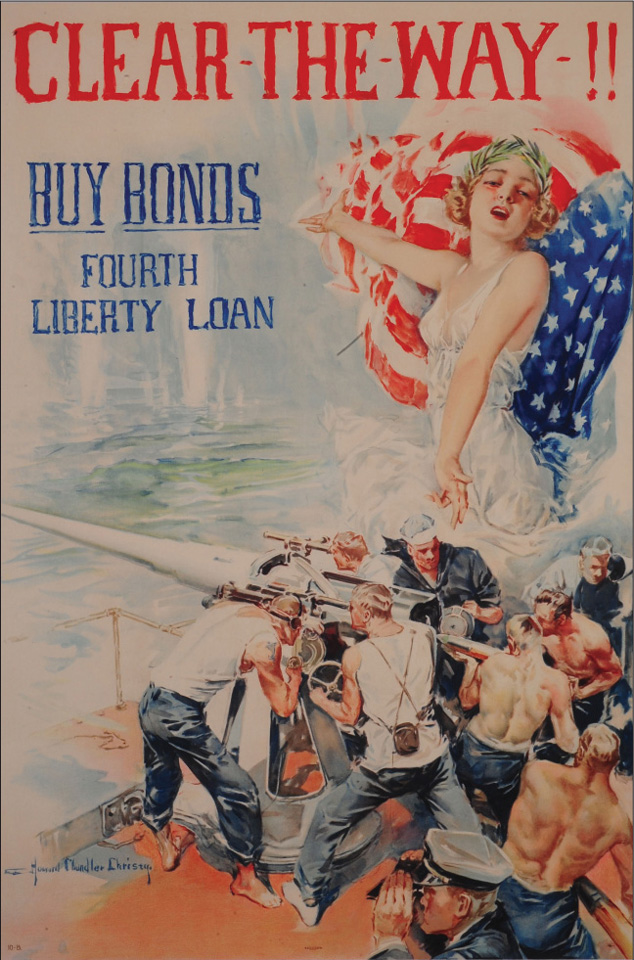

Continuing the marine theme, this fine piece of work by Howard Chandler Christie (1873–1952) depicts a muscled, toiling gun-crew in an almost Greek-heroic mould. Christie was no stranger to war art, having been employed as an artist during the Spanish–American War of 1898. As with his contemporary Harrison Fisher, it was Christie’s depiction of women, particularly the ‘Christie Girl’, that won him lifelong fame, and this is evidenced by the thinly clad girl encouraging the crew. After the war public taste in art changed, and Christie became a portrait painter, producing excellent works of half-a-dozen presidents, and numerous celebrities such as Amelia Earhart, Will Rogers and Benito Mussolini, among others. His massive work ‘The Scene of the Signing of the Constitution’ hangs today in the Capitol building.

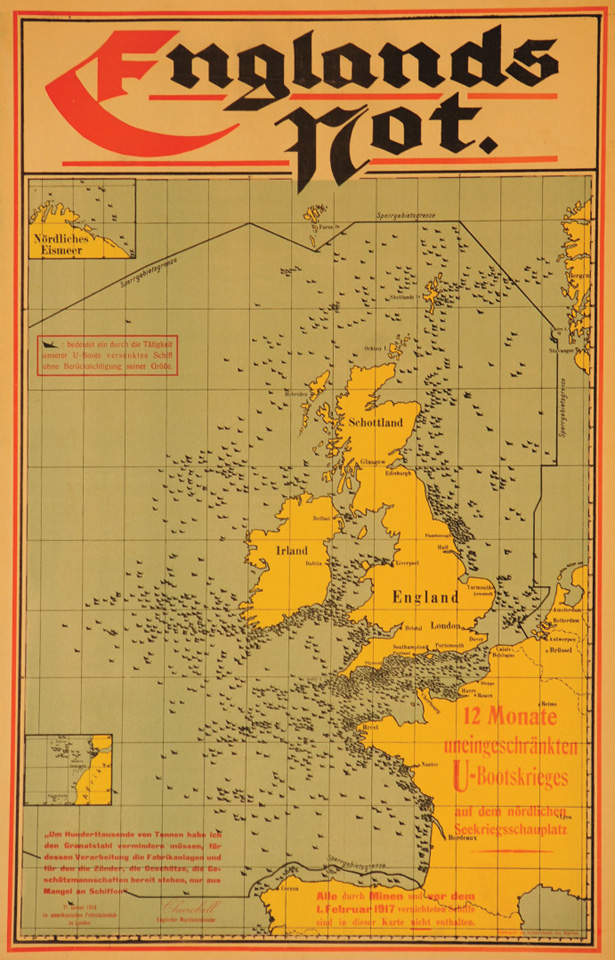

‘England’s distress. 12 months of unrestricted submarine warfare in the North Sea theatre. Ships sunk by mines or sunk before the 1st of February 1917 are not shown.’ The 1916 fighting convinced the Germans that the war couldn’t be won on land, and on 30 January 1917 for all-out submarine warfare. Ironically, this poster was produced when it was clear that this strategy had failed. It had not knocked Britain out of the war and had even encouraged the United States to side with the Allies.

‘The U-boat war. Average monthly achievement in the first half of 1918.’ The use in posters of seemingly objective documents to manipulate opinion can be traced back at least to the French Revolution. Even by using a dramatic visual image and unrealistic comparisons, this poster cannot hide the fact that by the summer of 1918 allied production was nearly three times greater than its losses to German depredation –and was rapidly increasing. The massive use of distorted figures would give the word ‘propaganda’ a negative overtone it didn’t have before the war.

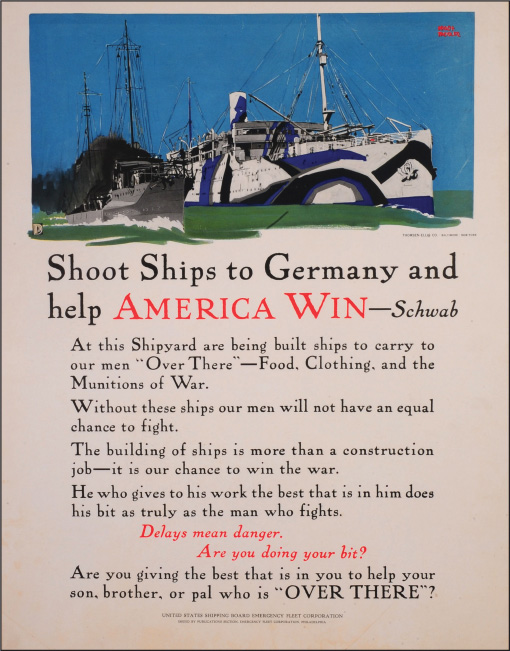

Not all the posters provided a clear message. This 1917 example from the United States Shipping Board Emergency Fleet Corporation has a rather obscure meaning, asking if the reader is ‘giving their best’, although in exactly what capacity is unclear. It is not a recruitment poster, but appears to be aimed more at workers, as the text is taken from a speech by Charles M. Schwab (1862–1939), owner of the vast Bethlehem Steel Corporation, who was accused of profiteering after the war. The fine artwork is by Arthur Triedler and depicts a dazzle-camouflaged merchant vessel.

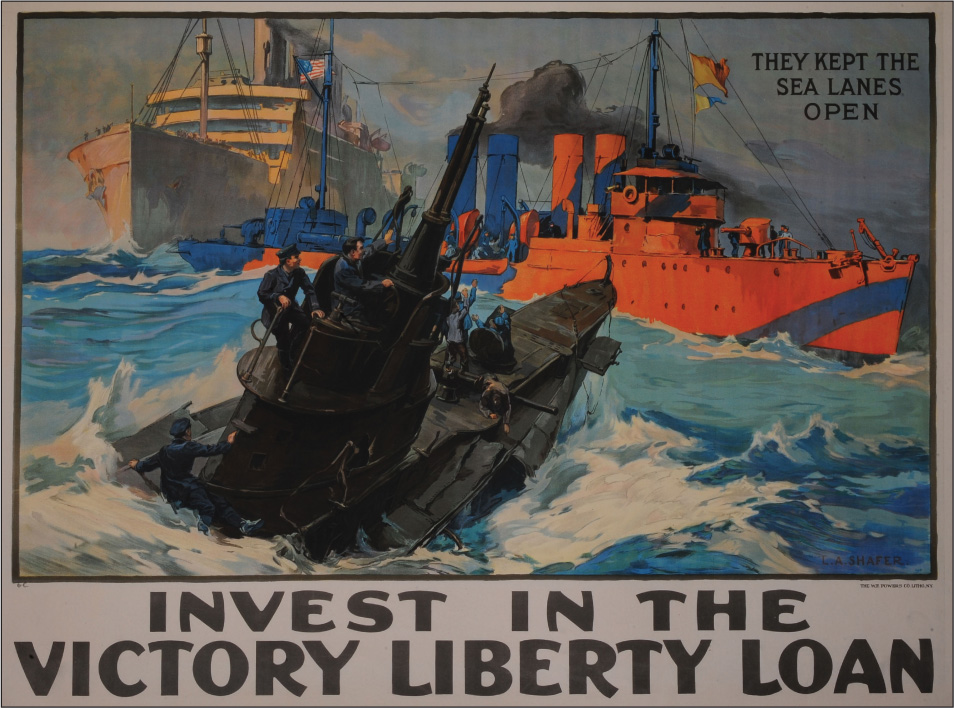

This marine poster is another with a confusing message, although it is more visual. At first glance the painting by Leon Schafer (1866–1940) appears to be showing an attack by a submarine on a merchant ship, but a closer look shows the submarine is sinking, implying that the destroyer has managed to disable it – in reality an unlikely scenario. There was no doubt that the food and munitions supplied to Britain by US merchant shipping managed to keep her war effort going, although at a cost. Britain imported £1,559,900,000 worth of food and war materiel between 1914 and 1918.

‘Big military concert!’ Concerts remained an important cultural activity throughout the war on all sides. For the Germans, it was also a way of showing their presence in occupied territory, just as the proud display of a (giant) trench mortar of the 4th Battalion on this poster is a way of showing the country’s military strength and therefore future victory. But music was first and foremost a way of relaxing. For professional musicians such as those mentioned on this poster, concerts proved indispensable, if only to keep their touch. Those who were not officially army musicians also found ample opportunity to practise their skills, including for the highest ranking officers.

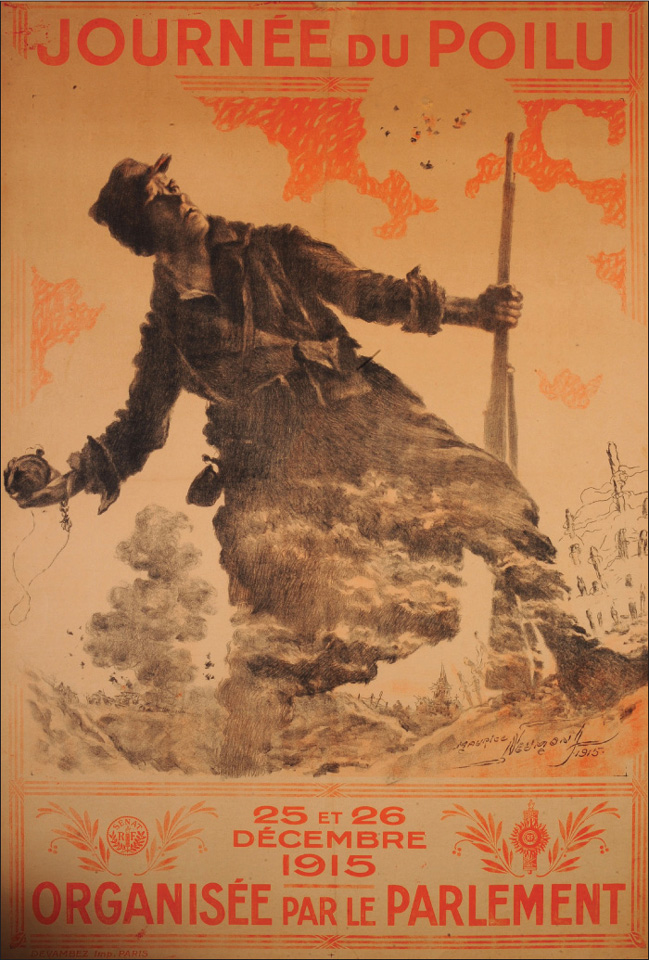

‘Poilu Day. 25 and 26 December 1915. Organised by the Parliament.’ Artists tried to follow the technological evolutions of the war. Facing the unexpected challenge represented by trenches, the warring nations had to resort to out-dated equipment. Siege warfare techniques and grenades were experimented with anew. This French Poilu is using a rudimentary hand grenade with a rather dangerous fuse. In 1915 the shortage of grenades was so acute that soldiers would improvise by filling old jam tins with powder and nails. In every country a whole new industry had to be created to answer the war’s needs.

‘Subscribe! and we shall have victory. National Loan 1918.’ Propaganda of all kinds equated technological superiority with certain victory. By 1918 images of tanks were well known to the public, especially in photographs showing them overcoming trenches and shell holes. Simay has here also very clearly rendered the tank’s function of opening a way for the infantry by crushing and snapping the barbed wire. His decision to add an unrealistically long cannon further accentuates the diagonal upwards movement. He thus creates the strong impression of a force capable of crushing any obstacle in its way.

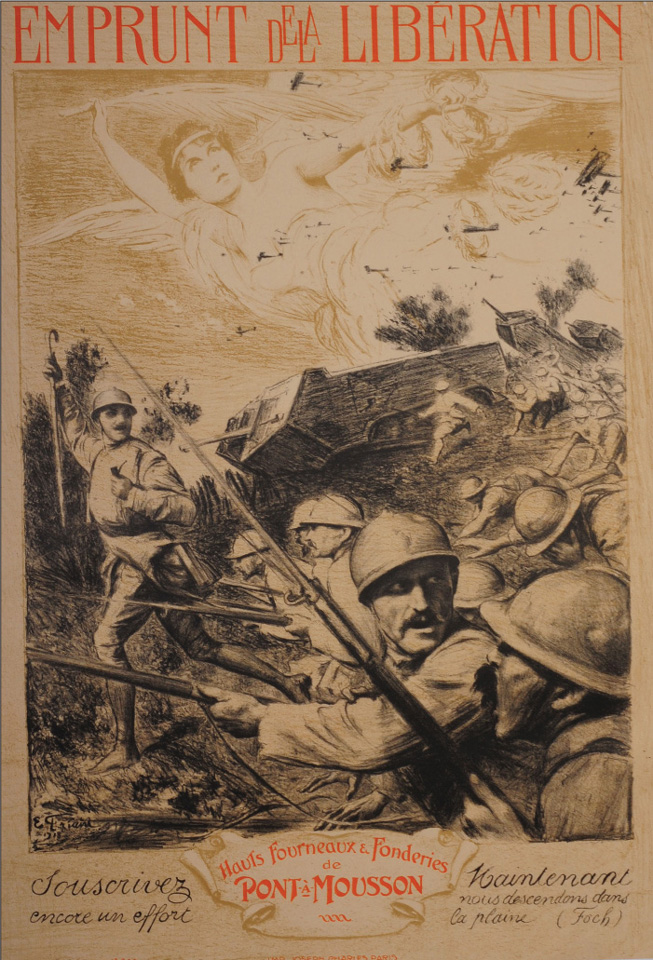

‘Liberation Loan. Subscribe now. “One more effort – we are descending into the plain” (Foch). Pont à Mousson Steelworks.’ As victory seemed finally possible, the Allies started using enthusiastic images of war again. As the town of Pont à Mousson had been almost part of the front lines for four years, pushing back the enemy was no abstract goal. This attack combines the determined French Poilu with a crushing material superiority: St Chamond tanks and a multitude of aeroplanes open the way. Here too, the allegory of Victory leads the attack, with a gentlemanly officer. The metal produced by the steelworks is shown to have a direct use in saving the city.

‘We’re defeating them – and you subscribe to war loans!’ Images became increasingly important as the war progressed because their message suffered little from contradiction or confusion. Ironically, showing the crushing power of (captured British) tanks focused the attention precisely on one of Germany’s weaknesses. During the Great War the German High Command dismissed tanks as an expensive, inefficient toy. By 1918, despite the reorganisation of all German industry towards the war effort, Germany was no longer capable of matching the Allies’ output: Ludendorff would later argue in his memoirs that the metal needed for tanks would have had to be diverted from submarine production. This poster is a classic example of propaganda turning a problem into an asset.

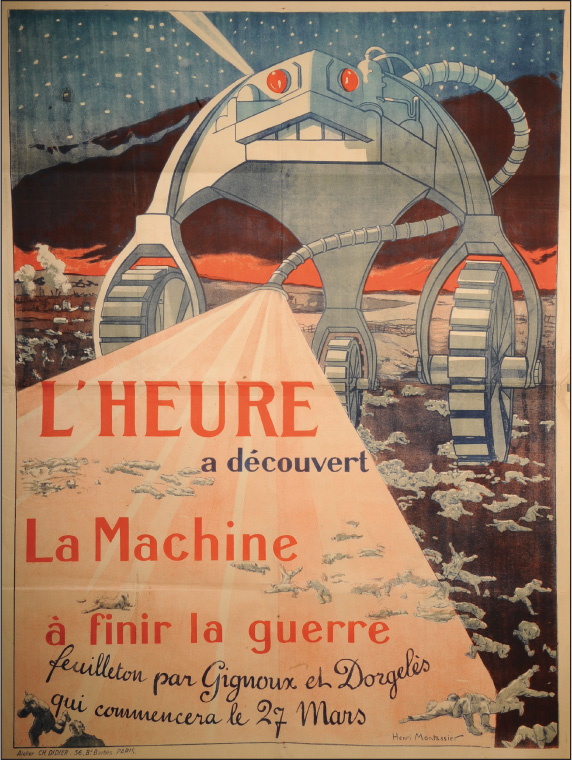

‘“The Hour” has discovered the machine to end the war. A novel in instalments by Gignoux and Dorgelès starting on March 27th (1917).’ Despite the widespread use of traditional figures, certain posters admired modernity and technical progress. This advertisement captures the violence of the war despite the novel’s satirical tone denouncing war profiteers and naïve patriotism. The poster combines the new weapons which so impressed the men of the times. The tank shoots gas to exterminate mercilessly the fleeing Germans. This image of total victory contrasts with H.G. Wells’s pessimistic views of alien invasion in the War of the Worlds (1898). The modernist approach opened the way to a whole generation of new posters in the 1920s.