The absolute conviction during the Great War of each nation’s superiority meant that allies were applauded for their intelligence and loyalty, but it also meant that enemies had to be lowered in the public’s estimation still further. Showing your enemy was the second most fundamental aspect of efficient propaganda based on attraction and repulsion.

Images of the enemy did not appear out of nowhere but were based on prewar differences in lifestyle, custom and attitude. These could be simply picked up in newspaper caricatures but may also have been justified by the church hierarchy or by prestigious intellectuals. During the war French scientists even claimed to have identified a smell that was particular to the Germans. All these elements combined to create unquestioned distinctions between ‘Us’ and ‘Them’. Distinctions could then be radicalised into a clear-cut separation of Good and Evil, Pure and Unclean, Holy and Beastly.

During the war the posters’ based their depiction of the hated enemy on, for example, historical imagery or on the rejection of his primitive or ‘twisted’ decadent social values. In this context figures of the enemy could range from simple depictions to fearful caricatures and even to completely dehumanised foes. In fact, the Great War can be characterised by its immediate radical mobilisation: the French produced innumerable representations of the hateful Germans within days of the outbreak of the war. They were systematically portrayed as barbarian Huns, and were often reduced to a mere spiked helmet. The Germans were less visually aggressive during the war, perhaps due to the fact that they had won their previous war against France and were, throughout almost the entire Great War, fighting on foreign soil. Nevertheless, they despised the British for what they considered an unfair involvement in the war based only on materialistic ‘business as usual’ considerations. After their defeat, and with the rise of communism, German posters would become far more overtly radical.

This begs the question of what kind of violence could be shown. Ridiculed, deformed, inhuman enemies were countless. Flows of blood, tainted bayonets and even mutilated bodies with their tormentors might also be shown. The depiction of atrocities of all kinds rang out as a warning against any demobilisation, and justified in Christian societies the act of killing. If the enemy was not human, it was morally more justifiable to eliminate him. It also prevented any attempt to find a negotiated peace, as it became unacceptable to negotiate with such monsters. Hateful images therefore had within them their own radicalisation.

However, violence was accepted only to a certain degree. For example, when Frank Brangwyn drew an American bayoneting a falling German soldier, the image shocked the public because it was disturbingly realistic. It seems that, in posters at least, showing the physical act of killing was often the limit: bullets are not shown tearing through flesh and the raping German was only hinted at with the image of a soldier dragging off a woman or a young girl.

Nevertheless, the most radical emotions could be stirred up against a clear threat, for the wildest, crudest fantasies could be drawn, and this process could be very useful in mobilising the productive effort needed to win the war. Posters about the enemy explain remarkably clearly how societies at war see themselves and their place in the world around them. Nowhere is national ideology more distinctly defined than in the representation of the enemy, the difference between the imaginary and reality so clear.

‘The enemy is listening in! Be careful!’ The telephone was widely adopted in 1915, before being replaced in 1916–17 by radio and other communications methods. In order to avoid interceptions, telephones were only used a mile away from enemy lines. Such posters existed on both sides of the Western Front. When the code war was finally mastered at a late stage in the war, the use of bluff became more widespread. For example, the Allies purposely reduced their radio signals before the 1918 Battle of Amiens.

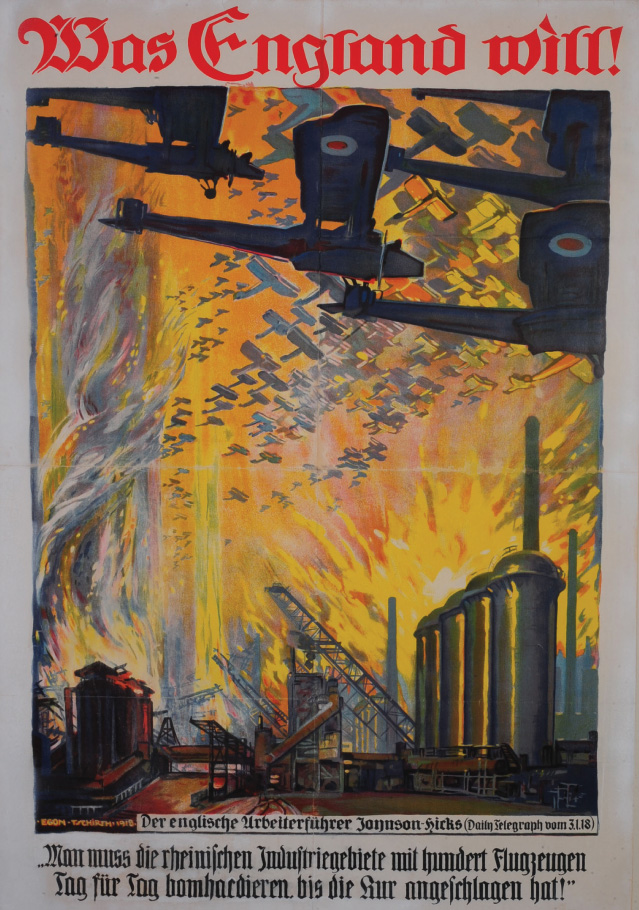

‘What England wants! The British trade unionist Johnston Hicks (Daily Telegraph dated 3 January 1918): “With hundreds of planes we must bomb, day after day, the Rhineland’s industrial area until the cure has taken effect”.’ By 1918 the new levels of violence induced by a total war were acknowledged by all. Aerial raids against cities and factories were already being carried out and made this poster quite credible to German audiences. Through stirring up fear and hatred of the enemy, it aimed at remobilising the German population which could otherwise have been tempted by a peace-making policy such as returning to the prewar status quo with no annexing of new territories.

‘How it would look in German regions if the French arrived on the Rhine.’ No major battle had taken place on German soil since the victory at the Masurian Lakes in the winter of 1914/1915. However, the war had made the Germans all too aware of the destruction wrought by an industrial war, and in 1918 they were still determined not to have to fight on their own territory. This feeling can best be summed up by the fact that the old patriotic song ‘The Watch on the Rhine’ had been turned into ‘The Watch on the Somme’ by 1916.

‘France’s raids. Germany, the romping place of the “peace-loving” French.’ The map of Germany shows the moves of the French armies during Louis XIV’s reign (1638–1715), the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), and the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars (1792–1815). It appears that the French have constantly pushed further into German territory. By ignoring conflicts such as the Franco-Prussian war of 1870–1871, this map makes it clear that no part of Germany would be safe in the event of an Allied victory.

‘The 7th Army “Art at the Front” exhibition.’ This original poster-drawing contrasts, in a humorous way, the French elite Chasseur with the supposedly cowardly German soldier. The French had a mental image of an enemy whose fighting power derived solely from brutal discipline. This representation of a degenerate German only too happy to be taken prisoner simultaneously reassured the French and denied their enemies any respect. Fighting was thus made easier because it was justified.

‘Bignon Bank Abbeville: “I make war”. Subscribe, the cleaning up will go faster.’ The humour of the Somme bank’s poster derives from the ‘hygienism’ approach to different nationalities. The strong, healthy French soldier is a model of masculinity, while his German counterparts are no more than helpless parasites. The surrendering figure and his fleeing comrade are both unarmed. The picture suggests a painless task of getting rid of them. However, the text suggests an emergency: Prime Minister Clemenceau’s famous words ‘Je fais la guerre’ show the total mobilisation needed to achieve certain victory.

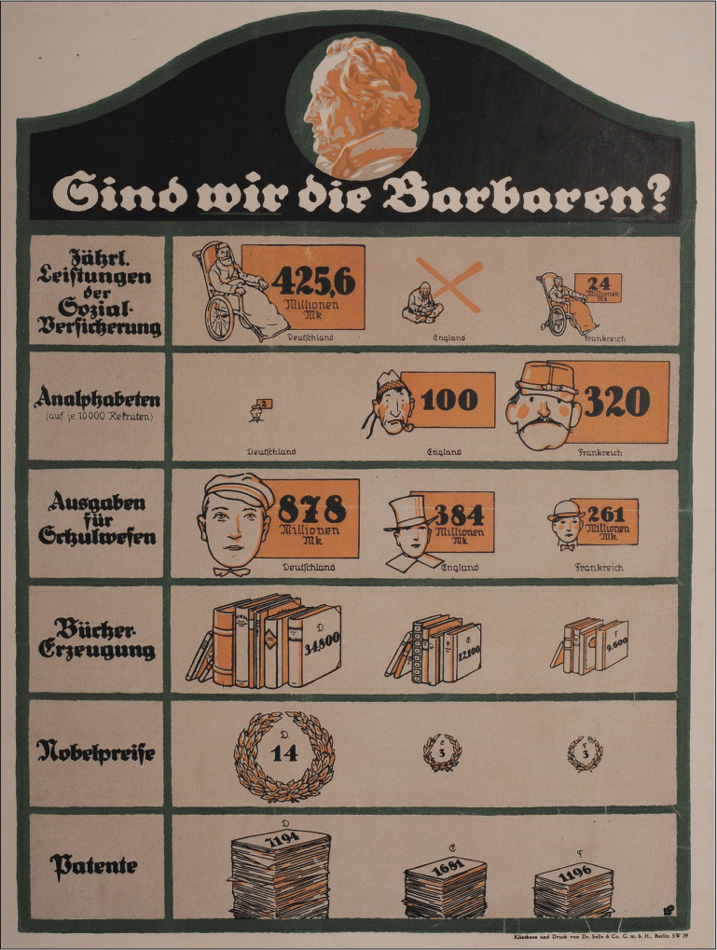

‘Are we the barbarians?’ German propaganda often used facts as a way of convincing the reader, instead of relying solely on the emotional impact of the image. This approach is based on a traditional view of propaganda: it is considered as an ongoing dialogue between nations, each offering its outlook on events. This poster compares the amounts spent on education and retirement pensions, as well as the number of Nobel Prizes and illiterates, in order to demonstrate German cultural superiority. Nevertheless, the war proved to be a turning-point in German political posters as even-sided arguments gave way, particularly in the 1920s and 1930s, to ever-more shrill and biased messages.

‘Here come the Americans!’ A humorous cartoon depicting a looming Doughboy and a cowering Crown Prince. Kronprinz Wilhelm was always portrayed in French caricatures as the ‘Prince of Thieves’, and always had a stolen object with him. Here ‘Little Willie’ is about to be punished. The artist’s optimism is justified by the boxes at the bottom, illustrating the huge amounts of munitions, food and men that the US was bringing into the war. The lower slogan points out ‘This is what America is bringing us.’ As a curious aside, the American soldier has a British Lee-Enfield rifle slung on his shoulder!

‘Subscribe for victory. National Bank of Credit.’ Although the artist, Michel RichardPutz, insists on the Allies’ victorious charge, he totally avoids actual combat and the act of killing. It is as if the enemy has already been destroyed. This illustration is typical of the way the war was depicted. It was easier to show the aftermath of a battle. In this case, the heaps of dead bodies and the piles of shattered cannon seem to have been caught by devastating fire while on the march, but blood is hardly visible.

‘Subscribe to the loan.’ In order to convince the public, many artists used widely accepted aesthetic representations. The female ‘towered Italy’ allegory dates back to the second century, when it already symbolised the sovereignty of Roman citizens. The enemy, stylised as a barbaric Gaul, serves as a reminder of the fall of Rome in 390 BC. By referring back to the traditional, classical opposition of Beauty and Ugliness, of Good and Evil, the artist Capranesi provides a clear link between the war loan and the halting of an impending invasion. By doing so, he also placed the Italians on the moral high ground: the allegorical figure of Italy is defending her honour and her land.

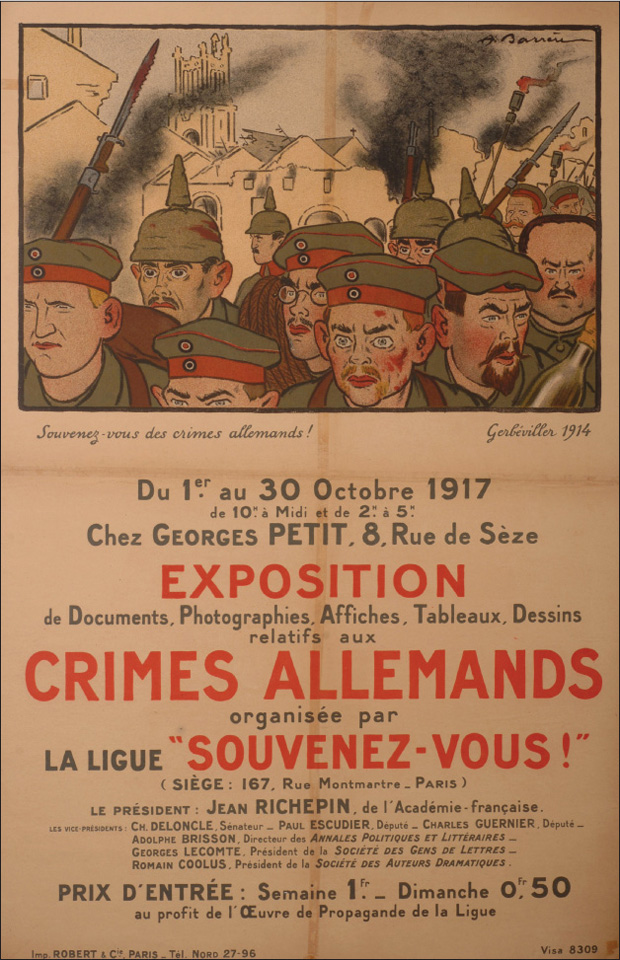

‘Exhibition of documents, photographs, posters, paintings, drawings about German crimes organised by the “Remember” league.’ Traumatised by the experience of the 1870–1871 war, during which French civilians shot them in the back, the Germans were determined to crush all resistance in 1914. In the first months of the war over 5,500 civilians were shot and countless buildings destroyed. These atrocities were denounced, sometimes with much exaggeration, by Allied propaganda.

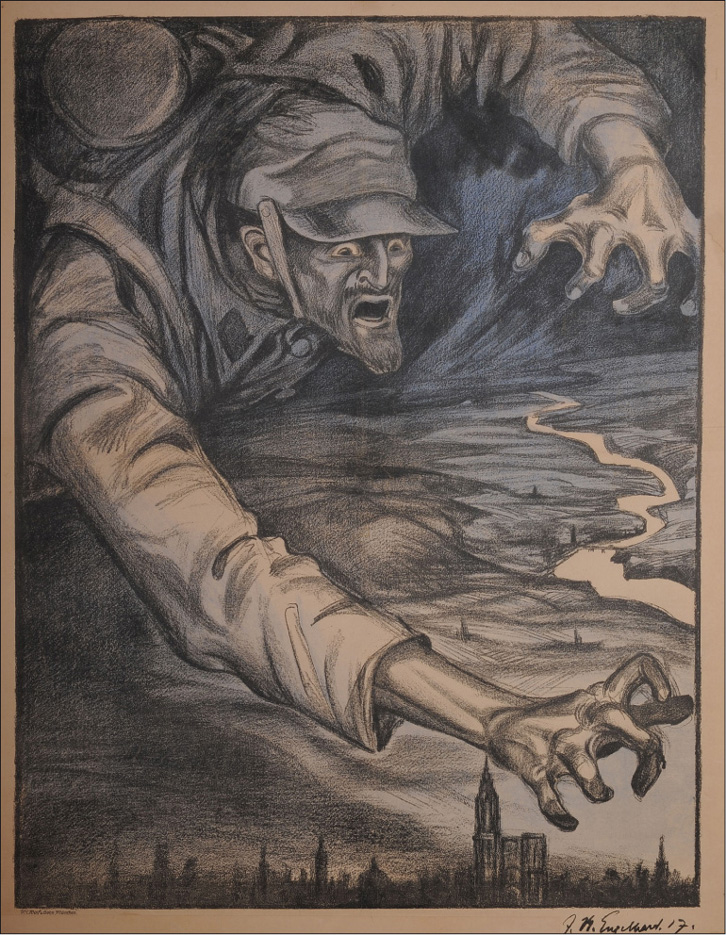

Though French propaganda was often more violent than its German counterpart (in part due to the fact that Germany was fighting on foreign soil), a substantial part of German propaganda did not hesitate to play on stereotypes and fears. The aggressive, grasping Frenchman looming over an idyllic Rhineland was sometimes accompanied by the text ‘No. Never!’ The postwar Allied occupation would reinforce the image of the horrible sub-human French soldier.

‘Remember Belgium and northern France. Buy nothing from the Boches. Printed in England.’ Denouncing German atrocities was an easy way to justify the war and keep soldiers and civilians mobilised. The horror of having one’s home and family attacked was a constant theme throughout the war. These horrifying images circulated around all the warring countries, and often the same theme might appear simultaneously in different places. There were also exchanges between artists who copied or imitated powerful new representations. It is interesting that this form of imagery was widespread even before war broke out. This French poster explicitly comes from England.

‘Once a German – Always a German!’ The economic war had preceded armed hostilities. Before 1914 commercial success was for many German industrialists also a way of proving their nation’s superiority. Their efforts were successful and entire sectors, notably children’s toys and chemical production, were dominated by Germany. During the war French and British posters played on both attraction and repulsion to condemn German products by ceaselessly reminding the viewer of German atrocities, many of them being pure fiction. By influencing postwar business attitudes, these posters encouraged a total mobilisation that went beyond military events, and also revealed the concerns of the day.

‘Remember!’ In the prewar years a product deemed to be German could ruin its parent company. For example, the Swiss-based Maggi Company came under constant attack from French milk retailers and the extreme-right Action Française. With the outbreak of the war the simmering hatred in major capitals boiled over: the fear of spies caused rioting, and foreign-named stores were sacked in various cities, including Paris and London.

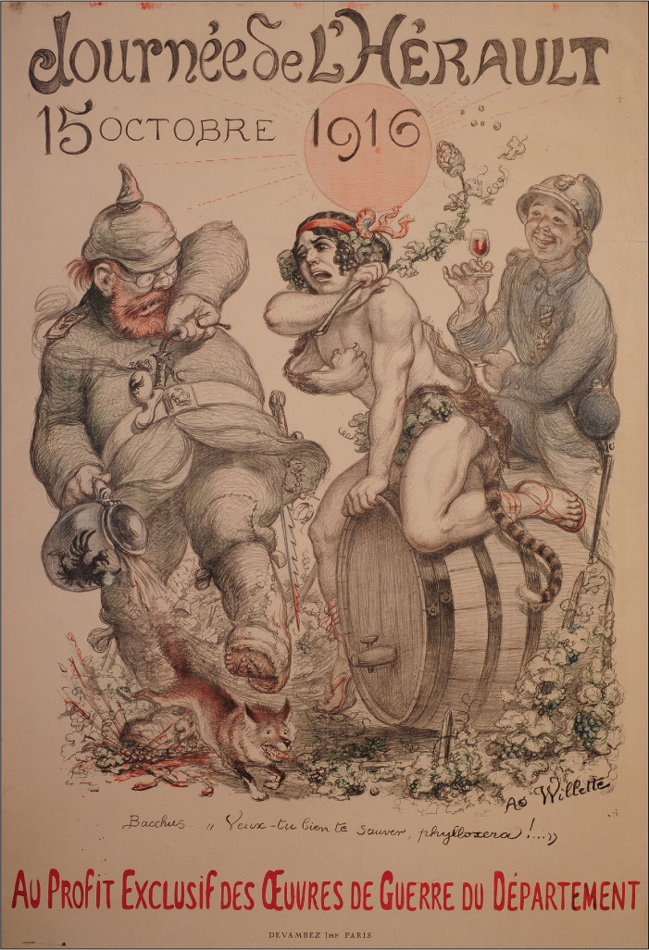

‘Herault Day, 15 October 1916. Bacchus: – “Go away, phylloxera!”’ In France some thirty-five National Days and countless Local Days were organised to raise funds for all kinds of cause. Volunteers sold paper, metal or even preciously crafted insignia or lapel flags, and over 1,100 different types are known. Just for the 75mm Cannon Day, 22 million insignias were made – more than one for every two French inhabitants! In this case the artist, Willette, has adapted a local concern: in one of the greatest wine-producing regions, he compares the beer-drinking German to the insect that devastated French vines during the nineteenth century.

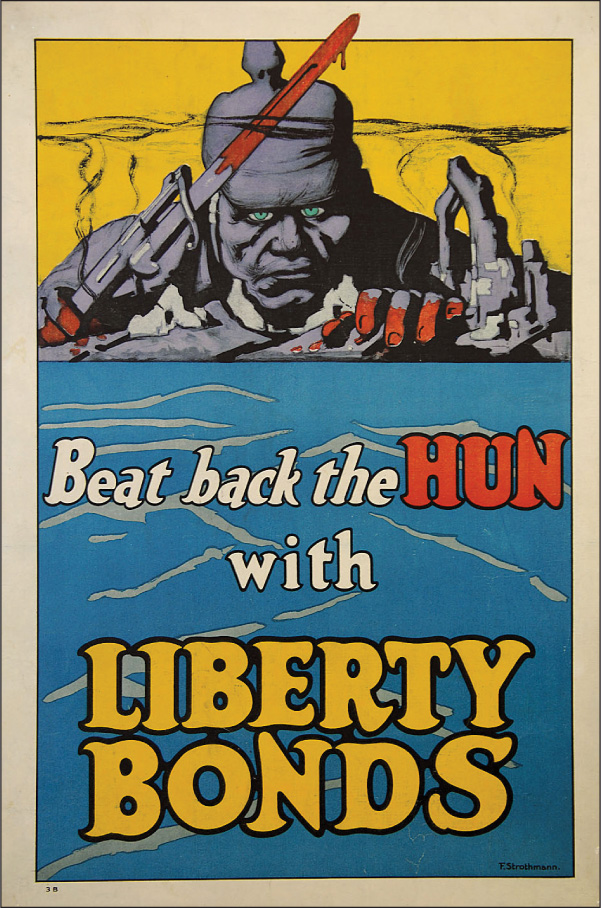

While the likelihood of German troops ever setting foot on American soil was virtually nil, the image conjured up in this painting is a clever one. The blood-soaked boots with their spurs bear more than a passing resemblance to cowboy boots, rather than jackboots, but the message is clear and graphic, if not entirely honest – buying war bonds would prevent the horror of invasion. It is typical of the posters depicting the enemy as inhuman, and played upon people’s most basic fears.

Unlike many of the allegorical images created in Britain and France, the majority of posters produced for the American public were of historical and rather heroic themes, relying on national pride and the ideals of justice and liberty. However, a few posters such as this one used images that were frankly quite frightening. This green-eyed, blood-soaked monster of a German soldier peers out from smoking ruins at the viewer. This was a late war poster, dating from 1918, and it uses the common epithet of ‘Hun’ for the German soldier. It was the creation of F. Strothmann (1872–1958), himself of German origin, who went on to become a well-known comic illustrator.

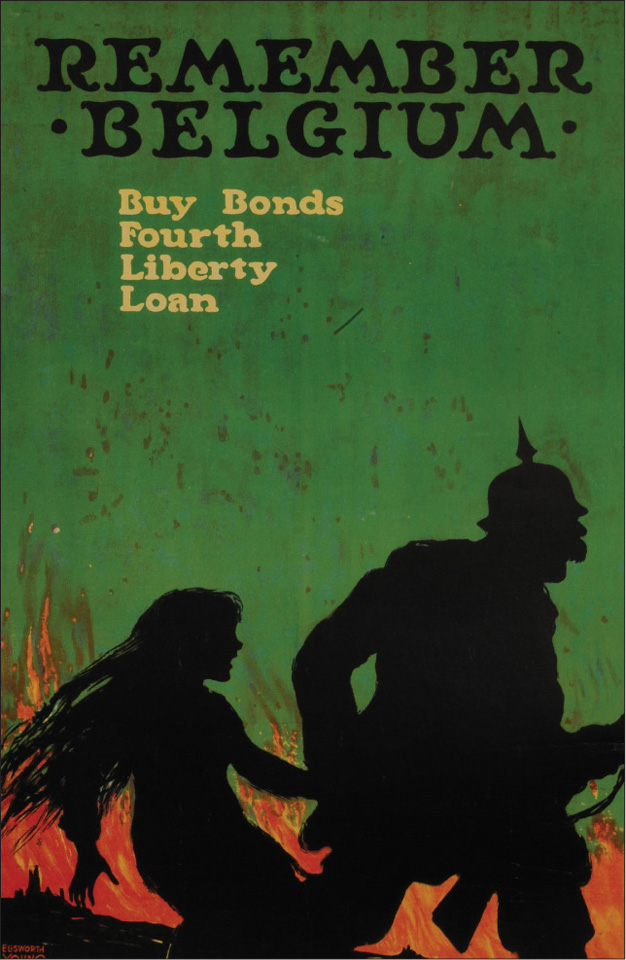

The last of the Liberty Loan posters, produced at the end of the war, this image by Ellsworth Young (1866–1952) is typical of a series showing the brutality of the German invaders. The picture is one of the more subtle and disturbing ones of the whole war, with its implied kidnap of a young girl by a typical picklehaube-wearing German soldier. Young was a very well respected landscape painter and book illustrator, and this cartoon-like image is an unusual but powerful piece of work.