In prewar Europe and the United States there was little interaction between the military and civilian populations in peacetime. Joining the army was often regarded as a last resort for men who were poorly educated or otherwise possessed few skills. Armies existed to fight for their flag and country but what they actually did was rarely reported and such fighting as took place was often in far-flung regions, where news of events filtered back slowly and had little if any impact on the civil population at home.

The First World War was to change this for ever, as it gradually became a conflict that encompassed entire populations and was widely reported. It was, in effect, total war: a concept that hitherto had never existed, where all civilians, from the wealthiest to the poorest, were affected in some way. It was not simply the sheer scale of the war and the numbers of men involved, but the requirement for entire societies to be mobilised to assist in the war effort, be it producing food or munitions, or helping with the wounded. Civilians became legitimate targets for the first time. Paris was bombed in August 1914 and suffered from long-range shelling in the spring of 1918, while German ships shelled the British east coast in December 1914. In 1915 the first Zeppelin raids were launched on London. No longer were the non-combatants at home remote from the effects of war. Curiously, this new danger fuelled greater determination on the part of civilians to help defend their homes. Lurid poster campaigns began in Britain and France, followed in both Germany and the United States, depicting the potential horrors of enemy invasion and asking, in many different ways, what the civilian population could do to prevent this happening. Workers were assured that their jobs, be they dock workers, miners or farmers, were vital to the war effort. To those not engaged directly in war work, the question was often posed, ‘What are you doing – does your job help the war effort?’ This was an attempt to persuade more people to work in munitions, or other industries directly related to the war.

In peacetime the female populations would not have been permitted to undertake physical work, the traditional preserve of the men-folk, but this changed very quickly during the war. By 1917 700,000 women were working in Britain in munitions alone, while in France an estimated 500,000 women were involved in war work, with some 80,000 working in jobs directly assisting the armed forces, such as driving, nursing or running front-line canteens. In both countries tens of thousands of women undertook hard labouring work on farms that were denuded of men. In Germany the situation was different as the attitude to traditional female roles was far more rigidly adhered to than elsewhere. Despite calls for women to be actively included in the workforce, the country relied on volunteers and these were not forthcoming in large numbers. The one exception was from the lower class of women whose traditional role had been servants, who embraced the opportunities for new employment. As a direct result of the wide social differences between the European countries, it will be observed that, while there are many examples of British, French and American posters exhorting women to aid the war effort, Germany produced far fewer.

The huge losses in men during the war also had a profound effect on family life, as the traditional role of the man as breadwinner evaporated. Thousands of families became dependent on the wages of the woman, the sole working adult, and this led to a gradual shift in both economic and political power as women demanded the same rights as men. This shift was reinforced by many men returning from the fighting, who were sceptical about political promises and wanted to see the old orders changed. This was particularly evident in Germany, where social privation and the economic collapse of the financial system led to open revolt at the end of the war. The effect that the war had on family and home life is probably impossible to quantify, but there is no doubt that the early attempts to persuade civilians to work for the greater good of the war effort would later have a major effect on how the war was perceived by people who were to be profoundly affected by it. As the Great War evolved from an almost medieval form of warfare into an increasingly mechanised and industrialised conflict, so too was the home front forced to adapt, and by the end of 1918 the concept of civilians as part of the war effort had spelt the beginning of the end of the traditional social roles that had existed through Europe for hundreds of years. The effects of this change are still being felt today.

‘The annexing of the left bank of the Rhine. The French war aim! Rhinelander, protect your freedom, subscribe to the 7th war loan.’ War aims were not really discussed at the beginning of the conflict. Some French military leaders, such as Foch, did later argue for the annexing of the left bank of the Rhine as a way of securing France’s borders. The depiction of Cologne Cathedral in flames echoes the French shock at seeing Reims Cathedral bombed. The fear of defeat was used as a way of remobilising the population.

‘Alsace-Lorraine Union. Frenchwomen! Hasten so that the year 1918 brings an Alsatian or Lorraine doll to a poor little girl. This will be a souvenir of our dear provinces where girls are even sadder and extend their arms towards France.’ The dolls, dressed in traditional clothes, serve as a reminder of French war aims. The French government had forbidden discussion of such aims but conceded in 1917 that the reconquering of Alsace and Lorraine was an accepted fact. In reality, as soldiers’ letters made clear, a great majority by then longed for peace and the resumption of a normal, traditional life, but less than 5 per cent of the population accepted peace without total victory. Children were used here as a way of sustaining morale.

‘Poilu Day. Finally alone! Organised by the Parliament.’ In 1915, with no end to the war in sight, a debate started about soldiers’ leave (which was not an automatic privilege in the French Army), and whether a much-needed rest with the family would boost morale. For those in the German-occupied regions, going home was almost impossible. An office was created to welcome these men in Paris, and it raised money through Poilu Days. Some 50,000 copies of this poster, one of six, were printed to advertise the second series of such Days. It simply depicts a reunited couple, and showing this longed-for situation proved very effective: coupled with the Christmas celebrations, these Poilu days were an unparalleled success.

‘From work to victory. From victory to peace!’ War weariness caused strikes and other delays in production by 1917. Throughout the war, and particularly in the later years, it was necessary to remotivate the population. The intention of this poster is to make overt the link between national production and the war effort, but it goes beyond the classic bond between the elderly munitions worker and the younger soldier, with the text promising not only victory but also, explicitly, peace. It was by then clear that propaganda had to explain that only greater sacrifice could accomplish the longed-for goal of peace.

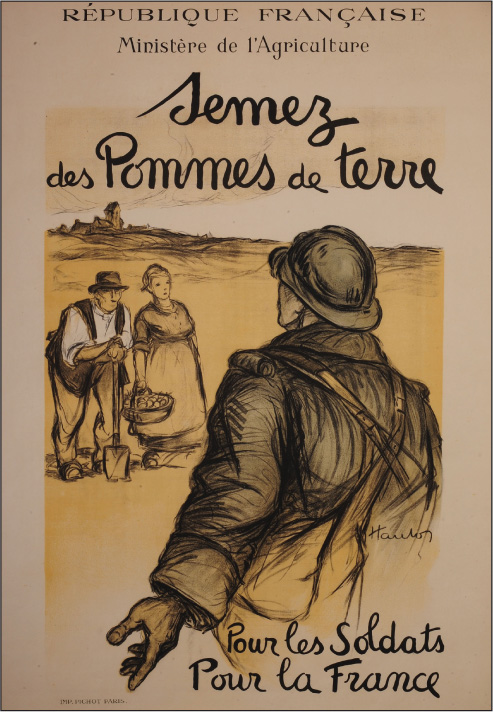

‘French Republic. Ministry of Agriculture. Plant potatoes. For the soldiers. For France.’ The occupation of northern France not only isolated the country’s strategic towns and industry, but also meant the loss of an enormous amount of agricultural production. Importing food from the colonies or from as far away as Latin America became indispensable. Free distribution of potatoes was widespread in French cities in order to counter food-price inflation and logistical difficulties. The instruction rests here upon the soldier’s moral authority to influence the farmer’s choices, but many posters would describe food production as the home-front’s battle.

The war brought about a fundamental change in the way women were regarded in the workplace in England, as tens of thousands took over roles previously regarded as male-only. With 6 million men in uniform, their contribution was vital in aiding the war effort. The Women’s Land Army was formed in 1915 as a civilian organisation that provided women to undertake agricultural work and, despite much opposition from conservative farmers, by 1917 there were over 250,000 women in the scheme. This image was painted by Henry George Gawthorne (1879–1941), who became famous after the war for his LNER railway posters.

Although rationing during the Great War was not as strict in Britain as it would be during the Second World War, by 1916 there were growing food shortages and England was particularly dependent on wheat imports from the United States. In a series of practical posters British households were reminded, using the key as a symbol, that waste was damaging to the war effort. The war years saw the emergence of the food blackmarketeer and severe prison terms were introduced for those caught buying or selling illegally.

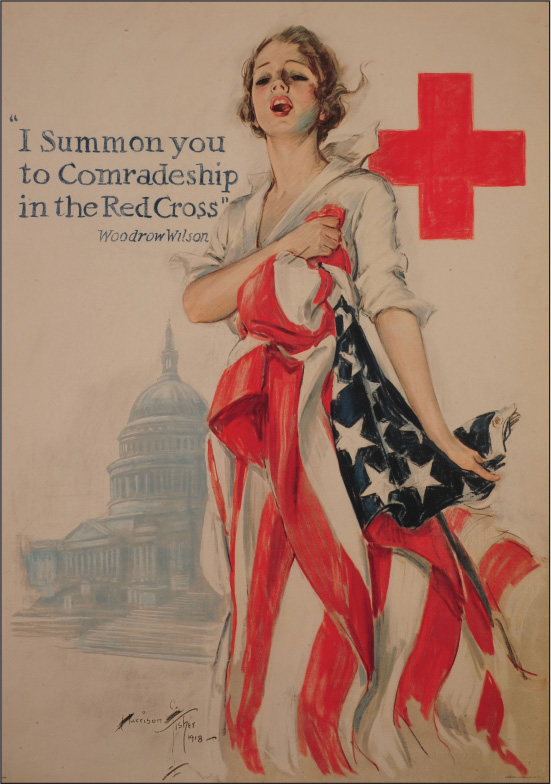

While the quote from President Wilson is clear enough, the actual image here is rather mixed, the woman apparently clutching the American flag with an unusual degree of joy. This is entirely due to the artist, New Yorker Harrison Fisher (1887–1934), who was known as ‘the father of a thousand girls’. His magazine and journal covers depicting coy but sexy women graced hundreds of dug-outs and mess walls during the war and were equally popular on both sides of the Atlantic, and ‘Fisher girls’ were highly sought after – although whether this poster aided the Red Cross effort is a moot point. After his death, one of Fisher’s relatives burned over 900 of his original works.

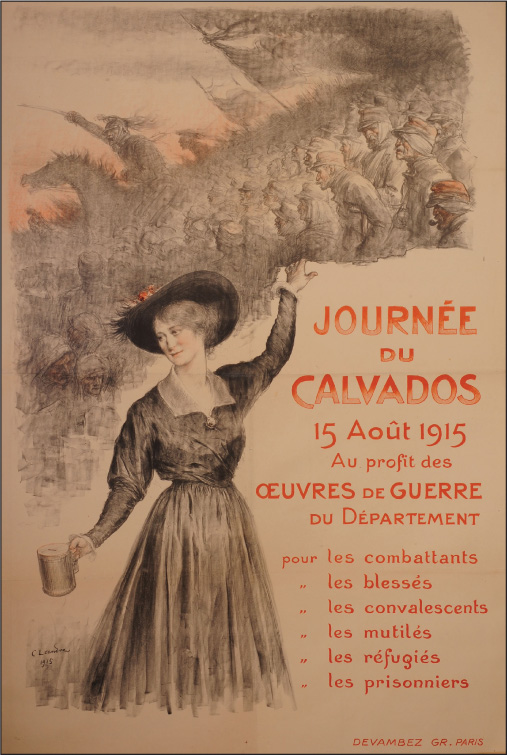

‘Calvados Day 15 August 1915. For the country’s war charities. For the soldiers, the wounded, the convalescents, the amputees, the refugees, the prisoners.’ Charles Léandre concentrated on the female and civilian audience: his drawing of a realistic woman in the midst of collecting donations prepared the population for what they were to expect on the Day. It also subtly calls for volunteers, giving women a role in the event and, more generally, in the war effort: they are to support, almost literally, as on the poster, the soldiers represented as a mixed mass of attacking and wounded men.

The United States had never shied away from the fact that money was the key to its war effort, hence the extremely large number of posters for liberty loans and war bonds, which comprised some 20 per cent of the total output of all posters during 1917–1918. This one, from 1917, is aimed very specifically at women, indicating that at this time women, in the United States at least, were regarded as having some measure of economic independence and also a personal view on the moral justification of the war with Germany.

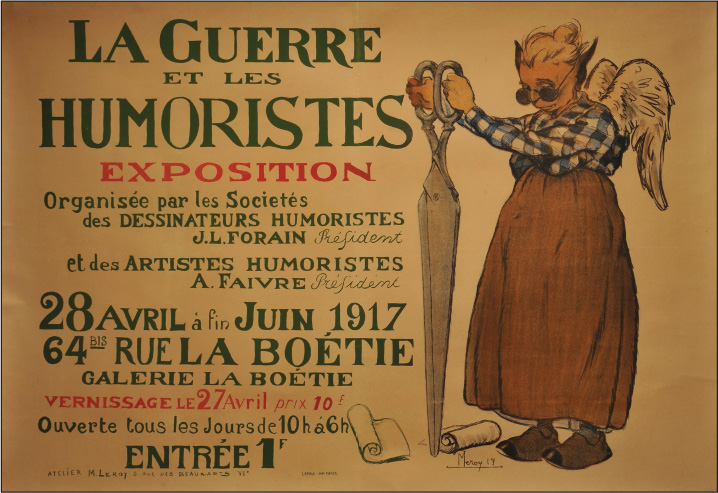

‘The war and humorists. Exhibition.’ The female figure of Anastasie with her great scissors had been an allegory of censorship since the French restoration of 1814 and may derive from the fourth-century ruler Anastase I. At the beginning of the war acts and laws gave powers of censorship to the military: the French still remembered that the Prussian Army in 1870 had simply read the press to know their movements. Everywhere, the sometimes difficult relationship between artists and censors was due to imprecise applications of overreaching laws. In most cases, it seems that self-censorship anticipated these difficulties.

‘Starting April 29th [1916] in “The Morning” read the infernal column by Gaston Leroux.’ The author of The Phantom of the Opera (1910), journalist Gaston Leroux knew how to prick the reader’s curiosity. Literary series were prized by newspapers because they ensured a faithful readership. The war only changed certain themes, and posters advertising famous authors continued the bookshop-poster tradition of the early nineteenth century. For authors, a series secured a steady income and was a good way to avoid being censored. For example, Barbusse’s Under Fire was left uncut because it proved too complicated to collect the instalments.

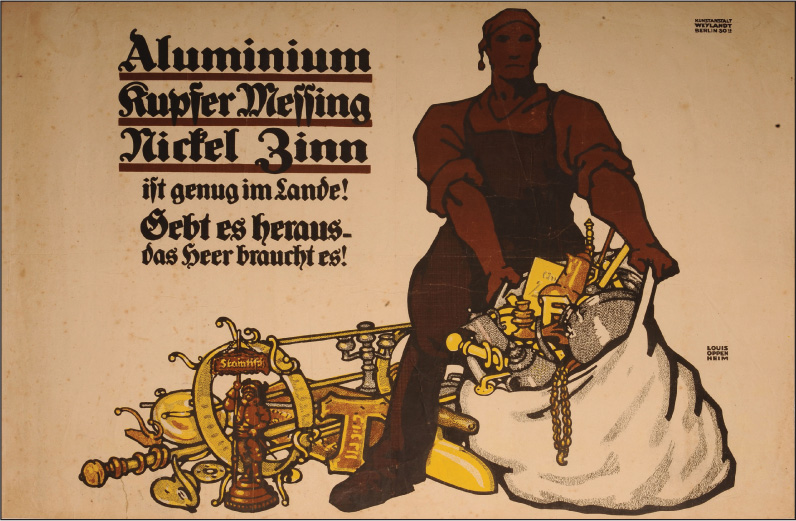

‘Aluminium Copper Brass Tin are sufficient in the land. Bring them out – the Army needs them!’ Louis Oppenheim’s triumphant Michel (an allegory of the German common man) distracts attention from Germany’s weak point. The British naval blockade had prevented Germany from importing many of the goods it needed for the war effort. The metals mentioned here were largely used to produce shells. Collecting resources was carried out to an even greater degree than in other countries, and occupied territories were systematically combed for their resources. Despite their efforts, German industries had to develop ‘substitution materials’ (‘Ersatz Material’) in innumerable fields.

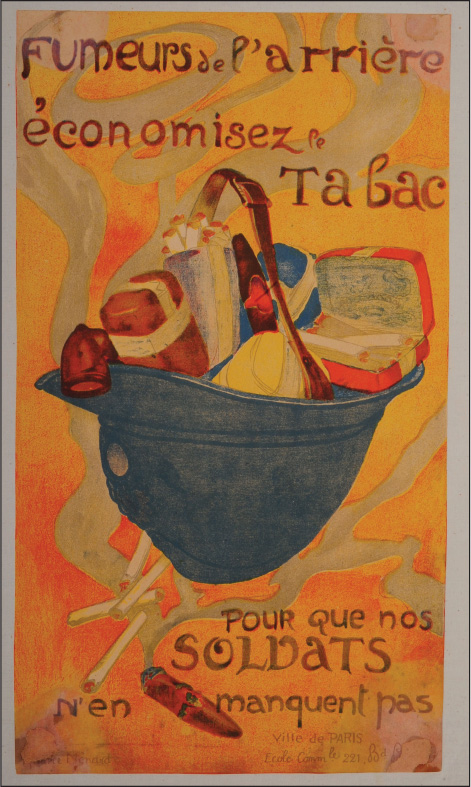

‘Home front smokers. Save tobacco so that our soldiers are not deprived.’ In 1917 the city of Paris held a contest in schools asking children to draw a series of posters about rationing. During the early twentieth century, smoking was regarded as part of a masculine, virile identity, and was even considered a sign of elegance. Giving up luxury goods for soldiers at the front was a socially encouraged manner of expressing one’s debt to the sacrifice the combatants were making. Because children were not supposed to smoke (an unofficial practice that nevertheless developed greatly during the war), it is more than probable that this poster’s theme was imposed by teachers.

‘With the card – we will have little but we will all have some. Break your sugar in two today to have some tomorrow.’ Yvonne Colas has carefully drawn a sugar-loaf to illustrate the text. Children were no longer passive or reduced to the role of potential victims justifying the soldier’s fight but, for the first time, were targeted specifically by propaganda. They were to be mobilised like their parents and even, as is the case here, helped to monitor the grown-ups’ conduct.

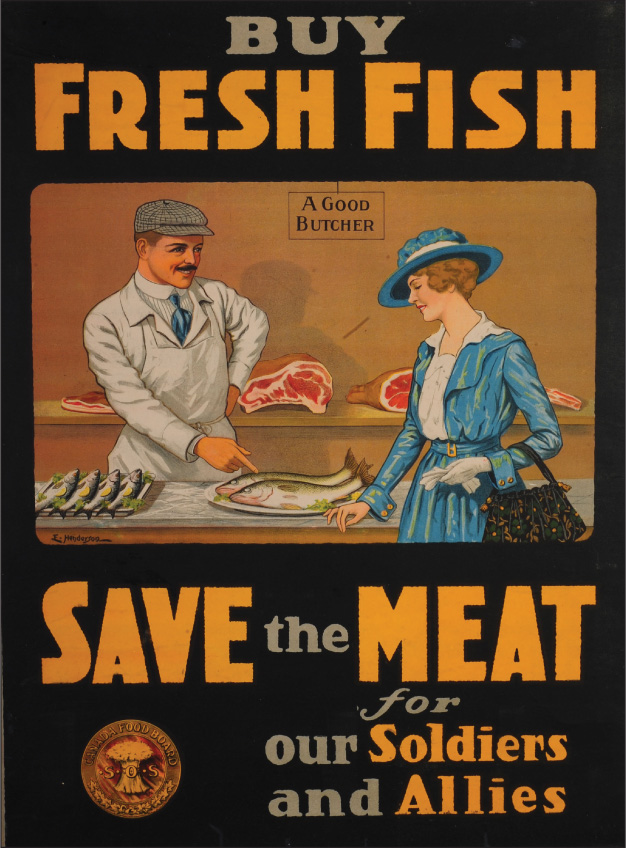

Another public information poster, implying that buying less meat would in some manner assist the fighting men. This basis of such a claim was highly doubtful, in view of the fact that most soldiers received army rations that were monotonous, nutritionally poor and often of indifferent quality. Fresh fruit and vegetables were conspicuous by their absence and most troops would have given a week’s pay for the succulent fish illustrated in this poster.

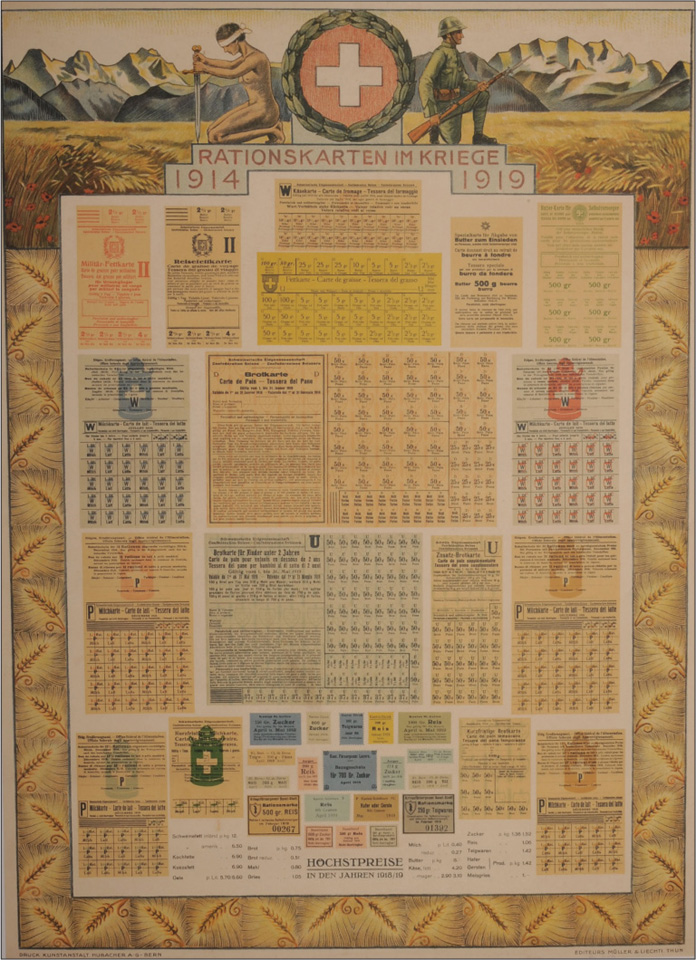

The war disrupted normal economic patterns and food became a major logistics challenge. For British troops alone some 3,250,000 tonnes of grain were sent to France during the war, despite the need to import 85,000 tonnes per month. The entire Australian and New Zealand meat production went to the war effort. But everywhere, efforts proved insufficient and rationing had to be introduced. Landlocked Switzerland produced a poster showing the great diversity of cards issued during the war.

‘War prisoner’s home-coming. Information. Advice. Help.’ The German soldier here is returning from a French camp, where his clothes had been marked PG (Prisonnier de Guerre – Prisoner of War). During the war over 9.5 million men became prisoners of war. German soldiers were kept in camps until the second half of 1919 as a means of applying pressure to Germany before the signing of the Versailles Treaty. The artist captures here the poignant moment when the returning soldier gets off the train but has no one to meet him. Despite the poster’s reassuring message, the social and economic reintegration of veterans proved even more difficult in defeated Germany than elsewhere.

‘The recovered home. Amiens show.’ The very modern graphic design of Le Cornec’s poster uses large surfaces of a single colour to offer a positive, dynamic view of the reconstruction. It is a reassuring view of a perfect household. The growing family echoes the rebuilding of Amiens, recognisable by the cathedral’s silhouette. However, though a bright future is promised by the poster, the barbed wire would not be completely removed from the Somme battlefields until 1931. The reconstruction process would often be long and difficult; many press articles compared the barren lands to a new far-west.

‘Devastated Aisne. War Charity for the reconstruction of destroyed homes.’ This Steinlein realist charcoal drawing sticks to an accepted aesthetic in order to transmit the dignity and suffering of the civilians and encourage help to change their current situation. As early as the German withdrawal in 1917 many displaced French families returned to their homes, only to find them wrecked by the war. Charity Days did not end with the war: on the contrary, they would go on well into the 1930s, focusing on war victims, wounded men, orphans and the plight of those returning to devastated homes. The great celebrations of 14 July 1919 also served as a way of collecting money for the reconstruction.

‘National Loan 6% after tax – 1920. We subscribe without fee at the Bank of the Seine.’ This poster reveals a certain mental demobilisation, for the war and its consequences are absent. The artist makes no reference to ideals or altruistic feelings, but depicts the simple common sense of a couple looking for the best investment. The figure of the French peasant is very traditional: age symbolised experience, while the family’s rural background was a reassuring guarantee of a safe, secure operation. Such farming imagery is relatively rare during the war, as propaganda often insisted on the figure of the soldier and was aimed at the more easily accessible urban classes.

This unusual and complex image juxtaposes a family eating and a half-constructed ship. The message – that ship construction had a direct link to having food on the table – was a very appropriate one by 1917, the date of this poster. Such messages were a sign of the times, for this image would have meant little two years previously, when there were no food shortages, but in the intervening years the U-boat campaign had come close to breaking Britain’s vital maritime supply lines. The artist ‘TF’ has not been identified.