At the turn of the twentieth century the cinema was a relatively new social phenomenon. Its rise reflected the fact that, for the first time, working men and women had more disposable income with which to enjoy themselves. Cinemas were particularly popular with the working classes, as they required no social separation, were usually easy to reach and cheap to attend, and were open at convenient times. In London in 1914 there were over 1,000 cinemas, or public halls that showed films, in Paris over 700 and across Germany some 2000. In the era of silent movies there were no language barriers so films made in Europe or the United States could be shown anywhere. As the war progressed, this international market shrank as ‘enemy’-made films were banned from the screens but in their place appeared more home-produced films. Indeed, the renowned Fritz Lang began his illustrious career in German cinema at this time. Gradually, all of the countries involved in the war began to produce newsreel film of the battles, some genuine, some less so, in an attempt to show how well the war was progressing. Probably the first documentary was made by A.K. Dawson, a cameraman attached to the Austro-Hungarian Army, who made an historic short film about the Battle of Przemysl in 1915; this film was widely shown in the United States. However, the best known and most historically significant of this genre was The Battle of the Somme, released in the summer of 1916.

This was the first film ever made that attempted to portray some of the realities of war to a mass audience. Audiences accustomed to entertainment and an escape from the realities of day-to-day life found the scenes of devastation, dead and wounded unlike anything they had seen before and many images are still contentious today. Such was the film’s effect that it was watched by more people in Britain than any other film until Star Wars was released in 1977. It also reinforced the role of the cinema as a major means of showing propaganda in a more subtle way. So important was the cinema that by 1917 Germany had partially nationalised its film industry by the formation of the ‘Universum Film AG’ and in the United States, Britain, France and other European countries the cinema was increasingly being used to send powerful messages to a wider audience than posters could reach.

The advent of the ‘entertainment’ war film was only a matter of time, of course, and it is ironic that the first was actually a silent comedy film by Charlie Chaplin called Shoulder Arms. Few war films followed the theme of comedy though, for after 1918 anti-war sentiment grew quickly and films were used to bring home the true horror and futility of the war. Films such as The Big Parade (1925) and What Price Glory? (1926) had anti-war themes, and with the advent of sound All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) became an international success. Many of these films used genuine locations and even employed veterans who re-enacted their military roles for the camera, and these early films have a ring of authenticity that more modern ones lack. Using aviation as a theme, some productions such as Wings (1927) and Hell’s Angels (1930) were able to use genuine aircraft that today would be priceless museum pieces. The posters produced for these films were usually colourful, dramatic and sensationalist, and they have become collector’s items in their own right. Great War cinema has remained topical: in 1969 Oh What a Lovely War – an eclectic mix of music, comedy and satire – was released and is arguably the best of its type ever to be produced. All Quiet on the Western Front was remade in both 1979 and 2009, and in 1981 Gallipoli was a surprise box office hit. With the centenary of the war approaching, there has been a corresponding rise in interest among the public and a more balanced approach is now being taken by films such as Under Hill 60 (2010), which was a true account of the work of Australian tunnellers. At the other end of the spectrum Warhorse (2012) has been an incredibly popular spin-off from the fictional stage play. When Charlie Chaplin filmed his Great War epic in 1918, he could never have guessed just what an enduring legacy would be the result.

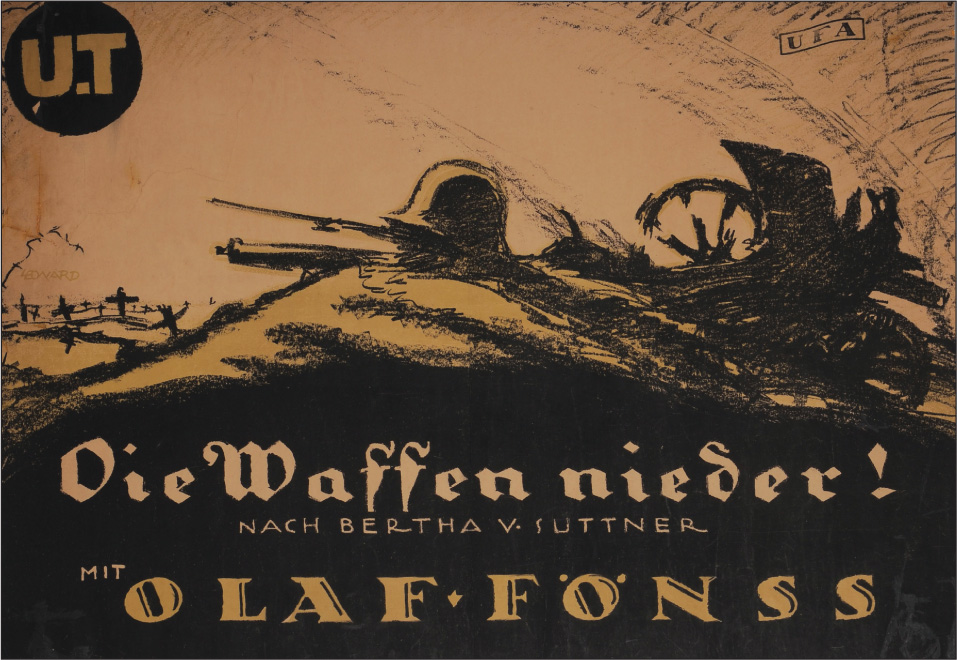

‘Lay down your arms! By Bertha v. Suttner with Olaf Fönss.’ Bertha von Suttner’s 1889 best-selling pacifist novel describes the sufferings of a woman through four of the nineteenth-century’s European wars. Inspired by the Austrian Nobel Peace Prize winner, the film was first released in August 1914, and then again after the conflict, when its posters featured a German steel helmet that did not exist in 1914. The rerelease was probably an attempt to show the film’s relevance in the aftermath of the war.

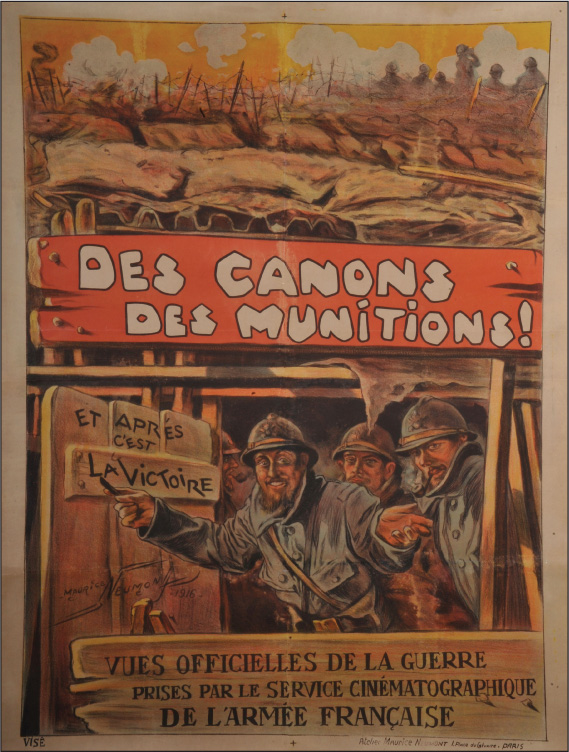

‘To die for country.’ At the beginning of the war no real system existed to capture the fighting on film. In France private companies were allowed to make their own newsreels, but in March 1915 the Section Cinematographique de l’Armée (Army Film Section) was set up. This merged in 1917 with its photographic counterpart to create a more centralised source of images for propaganda purposes. By then the battle was on for world-wide public opinion and all nations competed to produce their own versions of events.

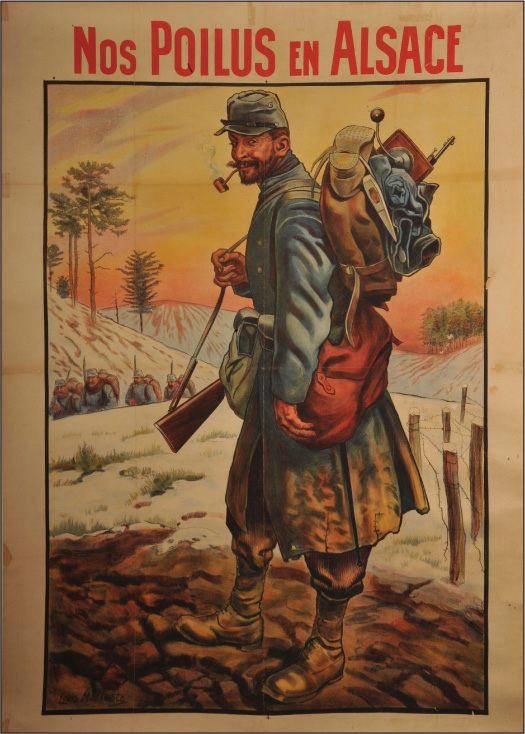

‘Our Poilus in Alsace.’ The poster artwork for this 1915 documentary film is finely detailed and realistic: for instance, the unofficial corduroy trousers are typical of the transition period from the red to the blue horizon uniform. The poster is directly copied from an image showing a cook with a coffee-grinder on his back at the Hartsmannwillerkopf. This summit on the Franco-German border saw heavy fighting in 1915. The soldier’s portrait was also turned into a postcard: during the Great War images could already be re-employed in various promotional ways.

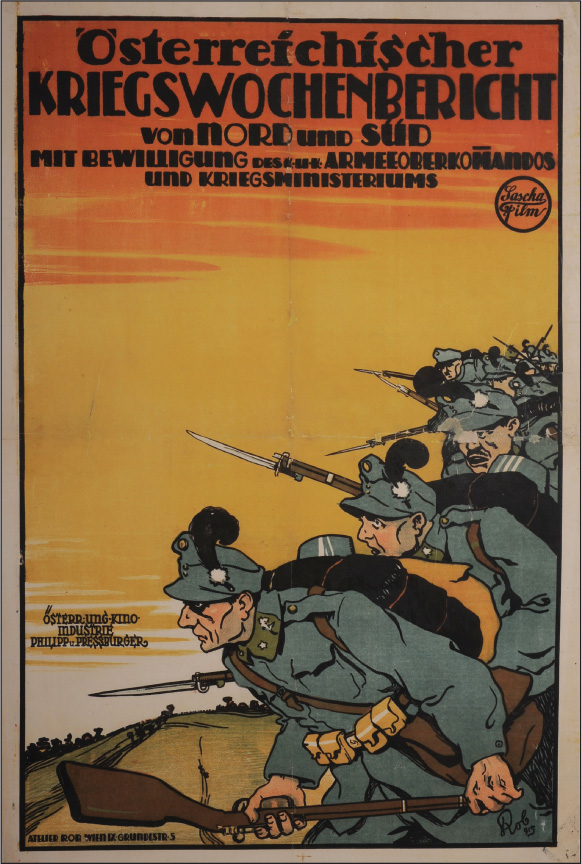

‘Austrian weekly war report of North and South, with authorisation of the Royal and Imperial Army High Command and of the War Ministry. Austro-Hungarian film industry.’ The war enabled Austria-Hungary to develop its own newsreel industry, an area previously dominated by the French. Its first weekly newsreel started in September 1914, before Sascha-Film also took on this new market, with more success. The poster is a typical representation of hunched-down Austrian soldiers attacking under a hail of bullets. The artist, Egger Linz, would further accentuate this tension in his most famous painting ‘Those who have lost their names, 1914’.

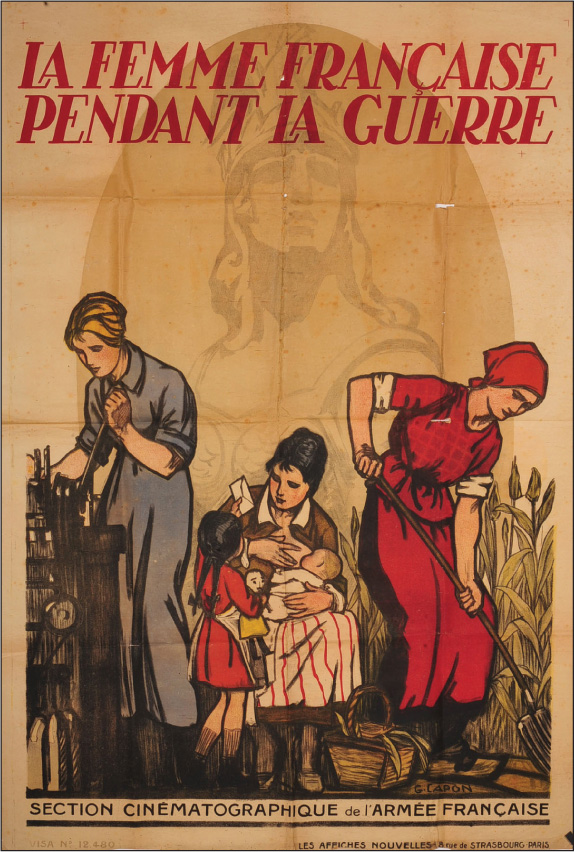

‘The French woman during the war.’ This 1918 newsreel, introduced by a short fiction, summarised women’s new role in the conflict. The poster’s direct, simple style was even more explicit. It combines various female figures. The allegorical goddess represents the ideals for which the French were fighting, while the traditional farmer taking on more physical tasks and the new factory worker symbolise the mobilisation of the home front. But the central image remains a reassuring maternal figure faithfully waiting for her man’s letters: many soldiers saw the sudden changes in the female role as a menace to their masculine identity and status.

‘Guns! Munitions! And after it’s victory! Official footage of the war taken by the Film Section of the French Army.’ Newsreels had an extremely important role in giving the public a vision of the war. This colourful poster (announcing a black-and-white film) promises a realistic view of the front and of the trenches, while simultaneously the cheerful men coming out of the shelter on the lower half make it clear that this official film aims at lifting morale.

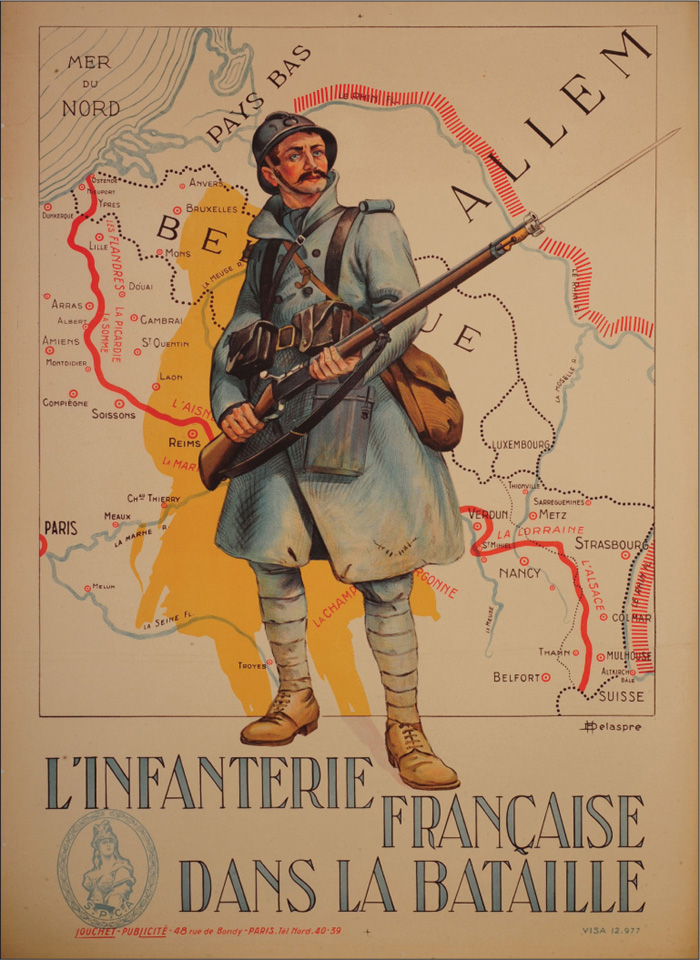

‘The French Infantry in Battle.’ The demand for images and a better understanding of the conflict remained high after 1918. Many families would treasure the official photographs they bought after the war, and these are still used to preserve family memories. The French Infantry in Battle documentary served a similar purpose: it is a chronological account of the military events taken from four years of official filming at the front. With the French Poilu defiantly standing guard before a map of the Western Front, the poster is a reminder of French tenacity throughout the war.

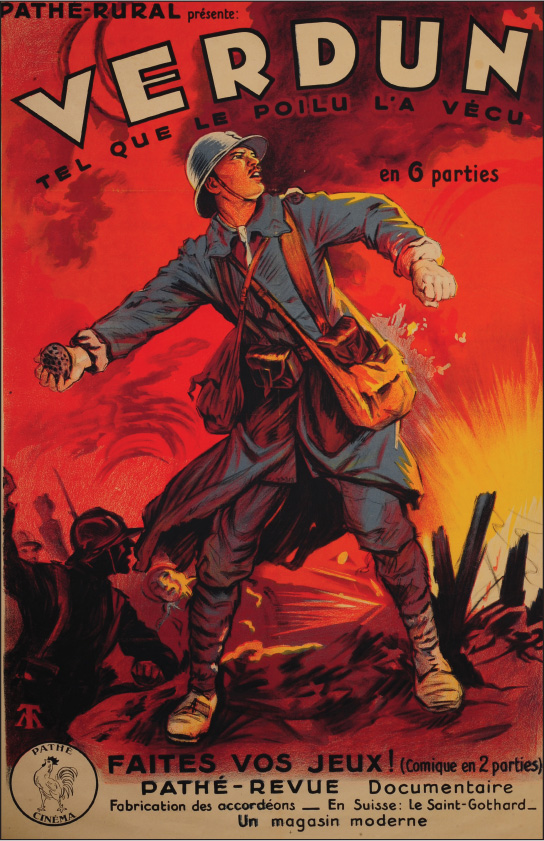

‘Verdun. Just as the French soldier lived it (in six parts). Place your bets (comedy in two parts).’ Pathé Rural was first used in 1926. It was hoped that ‘by bringing the cities to the villages’, the rural emigration process would be if not stopped at least slowed. Pathé Rural therefore aimed at bringing educational films to villages but it was also a way to cut costs. Emile Buhot’s 1927 Verdun is part of the commemorative production industry that blossomed ten years after the conflict. However, as this poster makes clear, serious films were not always sufficient to attract the public.

‘Verdun visions of history. The attack.’ Refusing to adopt an American melodramatic style, Léon Poirier decided to make a more authentic film. In 1927 he shot Verdun visions of history on the actual battlefields using, for the first time, both French and German actors. The film’s epic description of the battle was also an epitaph to all war victims and a means of educating people against war. Ironically, the superb images, filmed as if from the soldier’s viewpoint, are still used nowadays in war documentaries.

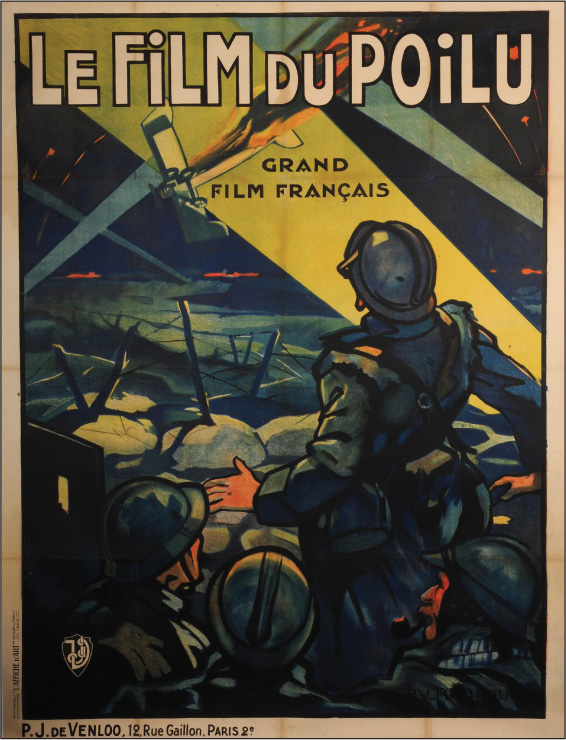

‘The film of the Poilu.’ Like many filmmakers of the late 1920s and early 1930s, Henri Desfontaines wanted to create authentic images by mixing archival footage, fiction and first-hand accounts. There is a moralising, rather pacifist tone to them, and such films condemned the supposedly increasing forgetting of the war. With the help of shocking images, it tried to reactivate the horrors of the trenches in order to prevent history from repeating itself. This was typical of French war veterans in the late 1920s and in particular of Daniel Mandaille: twice wounded at Verdun, he became a moral guarantor and also acted in three other films on the Great War, advocating realism in style and pacifism in content.

‘Block-heads.’ Laurel and Hardy’s 1938 comedy starts with a serious subject: Stan Laurel doesn’t know the war is over and is still standing guard where he was left before his unit attacked. Later, Oliver Hardy believes his former mate has lost a leg and decides to help the veteran. Though the rest of the film is based on classic comedy twists of two 1928–1929 shorts, it reveals the lasting impact of the Great War, especially at a time when the United States was looking on at the rising tensions in Europe.

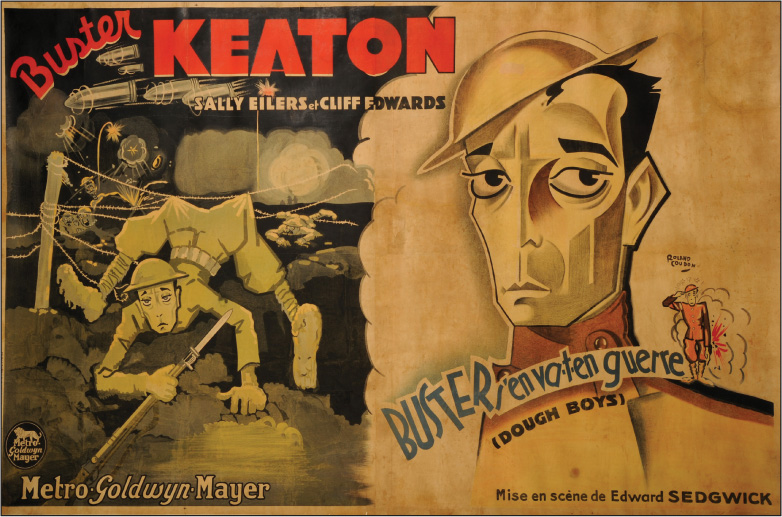

Despite the general trend in the late 1920s, not all films aimed at educating their viewers or at making a statement against war. The comedy Doughboys accumulates different sketches without aiming at any realism: for example, Buster Keaton accidentally volunteers for the army. Minor films would also use the Great War as a backdrop.

‘All quiet on the Western front.’ By the end of the 1920s, like many others in the film industry, Carl Laemmle Sr had become a pacifist, despite his 1918 pro-war films. His adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s novel started on Armistice Day 1929. The poster, showing Kemmerich’s agony, focuses on the mutilation and death of a whole generation. Despite glowing reviews, the film would be cut in many countries, not least in Germany, where Nazi supporters disrupted the film’s premier by releasing mice and coughing powder – the resulting rioting led to the film being banned. Goebbels had it censored and forced Remarque into exile.

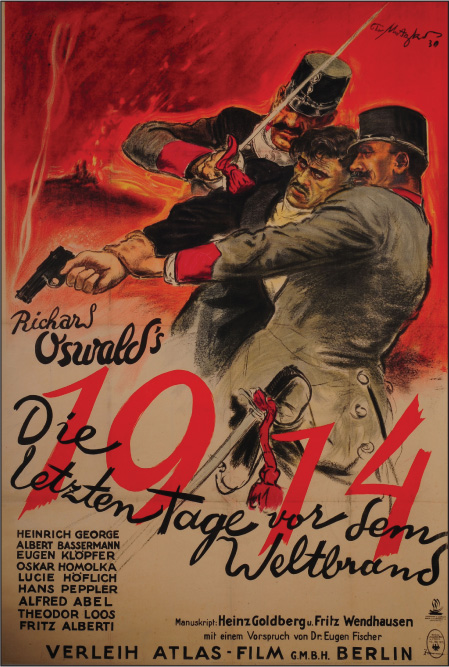

‘Richard Oswald’s 1914. The last days before the world fire.’ Richard Oswald’s 1931 anti-militarist film was severely criticised by the German conservative press and triggered a censorship scandal. Based on the diplomatic records of the Imperial Court, it showed the events leading up to the outbreak of the Great War. Though the poster focuses on the most dramatic moment – Gavrilo Princip being arrested after killing Archduke Franz-Ferdinand – the film was disappointingly stiff. Oswald went on to make, among many other productions, the first horror film. As a Jew, he then had to flee Germany when the Nazis took power.

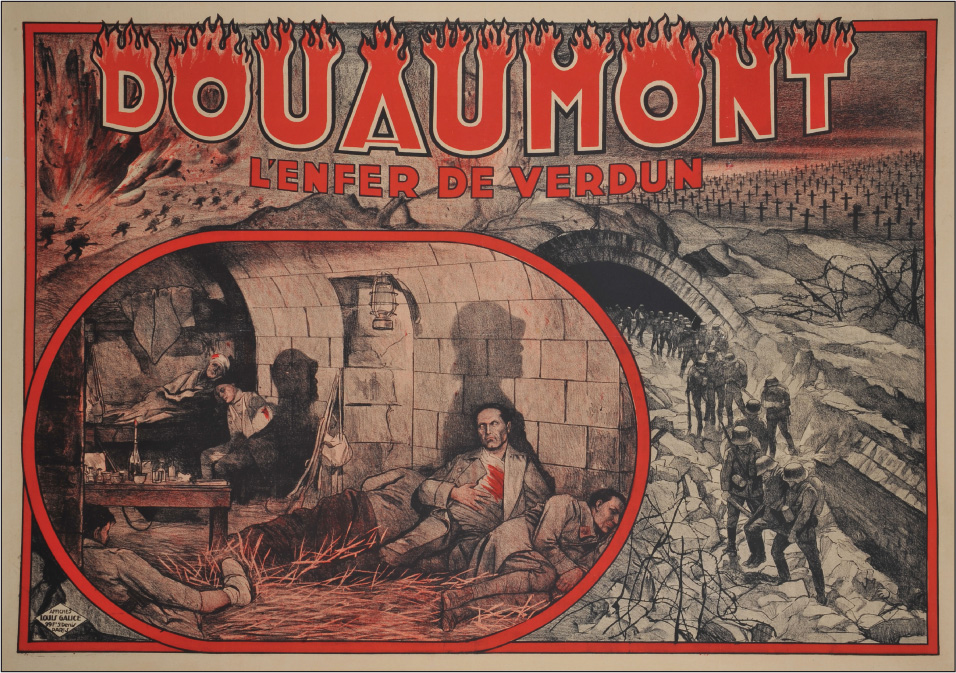

‘Douaumont. Verdun’s hell.’ Poster and film alike are not centred on individuals but try to embrace a common experience of total war: Heinz Paul offered a pacifist vision of both sides through archival evidence. His 1931 production is therefore more concerned with the multitude and realism than with individual story-telling. Creative liberties were still considered to show a lack of respect for the sufferings caused by the war.

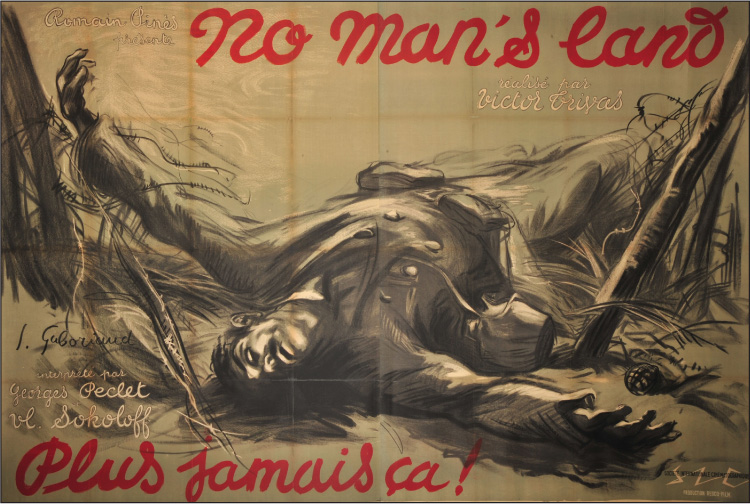

‘No man’s land. Never again!’ Victor Trivas, a German of Russian origin, adapted Leonhard Frank’s work to create a pacifist film: as a symbolic reflection on the creation of Europe, the war is in fact off-screen. Five soldiers from various countries are stuck together in a shelter in no-man’s-land and progressively learn to survive together. As in many of the 1930s films, hatred of the enemy evolves into hatred of war in general. In this case the film is also a call for class consciousness to prevent capitalist wars where only the lower classes suffer.

‘Grand Illusion. The masterpiece of French cinema.’ Grand Illusion first came out in 1937. Mostly set in a prisoner of war camp, it shows values like patriotism, honour and sacrifice, but also defines the tensions between social classes, and the hopes for peace despite these differences. More complex than most previous films on the subject, it was a worldwide success, though it disappeared, along with the original poster pictured here, from French screens in 1939 as it was seen to encourage alliances with the enemy.

Interest in war films fluctuated with time, and they were often released to coincide with war anniversaries. Compared to a number of generally anti-war films such as What Price Glory? (1926), Sergent York was slightly different; a biopic of the United States’ most decorated soldier, it remained reasonably faithful to the true story, earning Gary Cooper an Academy Award for best actor in 1941. It is somewhat ironic that within a few months of the release of the film, the United States would once again embark on a world war.

Paths of Glory was a 1957 film by Stanley Kubrik. With a typically anti-war stance, it was a dramatised version of the real-life trial of four French soldiers who were selected at random for execution after a failed mutiny in the wake of the disastrous Nivelle campaign of spring 1917. In France this film was regarded as an insult to the country’s contemporary involvement in the Franco-Algerian wars, and it was not released to the public until 1975. This particular poster carries the rare ‘Passed by Censor’ stamp.

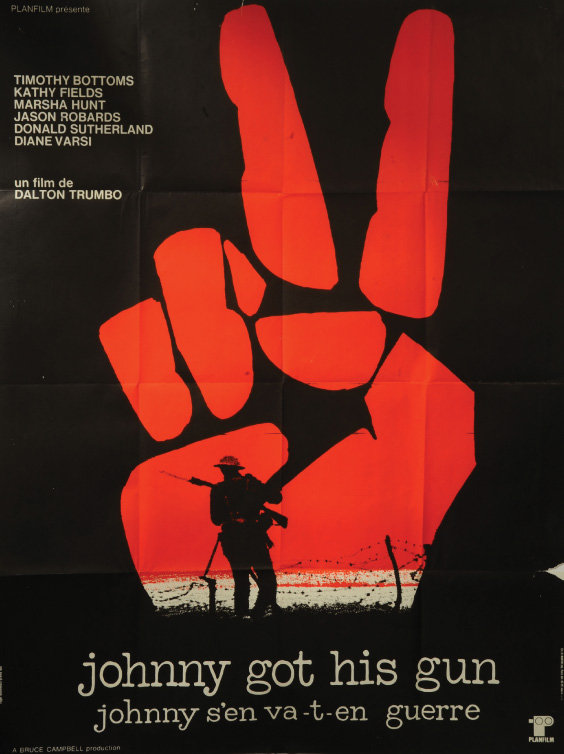

Most films about the Great War made since the 1920s have been of a critical or anti-military nature but this film, based on a book written in 1938 by American screenwriter Dalton Trumbo (1905–1976), took this stance to a new level. It is a virulently anti-war story about a young soldier, Joe Bonham, left deaf, blind, dumb and quadriplegic after being hit by a shell. It was broadcast as a radio play in 1940, and adapted for the screen in 1971 in the midst of the United States’ unpopular involvement in the Vietnam War. The stage play, first adapted in 1982, has since been performed worldwide.