The war did not end with the fighting. It would be another seven and a half months before peace would be officially signed in Versailles with Germany, and in other cities around Paris with the other defeated countries. By then, cross-border skirmishing (when it was not outright civil war) had erupted throughout central and eastern Europe. Entire new countries, such as Poland, Czechoslovakia and the Baltic states, had appeared, while others were reduced or recomposed. New political systems such as Bolshevism were threatening more traditional structures. On a more individual level, countless families were in mourning and millions more suffered from physical or mental wounds. About one in eight of the men who served had died. The consequences of the Great War would continue to profoundly affect societies long after its conclusion.

This impact was naturally also reflected in posters of the postwar period. Immediately after the conflict the return of the soldiers was on everyone’s mind but the sacrifices endured also had to be honoured: remembering the dead, taking care of the wounded and rebuilding the devastated regions was far more important than the archetypal image of the ‘roaring twenties’ would have us believe.

The political turmoil also created innovative posters. Though they were not concerned with the legacy of the Great War, the Russian revolutionary artists looked towards a much brighter future, and they brought new abstract figures and a modernist approach. The influence of cubism and of simplified forms grew in the inter-war years. The clear, almost architectural drawing concentrated on the message without insisting on the artist’s virtuosity. But these new approaches did not entirely eliminate well-tried representations. Themes of the Great War were reused constantly: the figures of the warrior and of rallying symbols, hatred of the (political) enemy, the glorious past, the sacrifice of the dead for the living were all employed to justify different convictions. Examples covering the variety of the political spectrum demonstrate that war was still a central preoccupation: the right reacted to the rise of communism and produced a wide range of violent, visually striking posters. The Nazis, who had never accepted the 1918 defeat, would continue referring back to the Great War in their Second World War propaganda. Most left-wing posters remained in the more typical charcoal drawing style and promoted peace as a solution to the challenges of the times.

At the same time remembrance remained a strong theme. Pilgrims visited the battlefields in search of a lost soldier or to see what the landscape looked like. This phenomenon has not waned in a century, and new generations continue to travel to Thiepval and other monuments. At regular intervals, especially on anniversary dates, new posters are still produced to commemorate the Great War, or at the very least to evoke it – a sure sign of the vitality of remembrance and of the lasting impact of this period on our societies and our world.

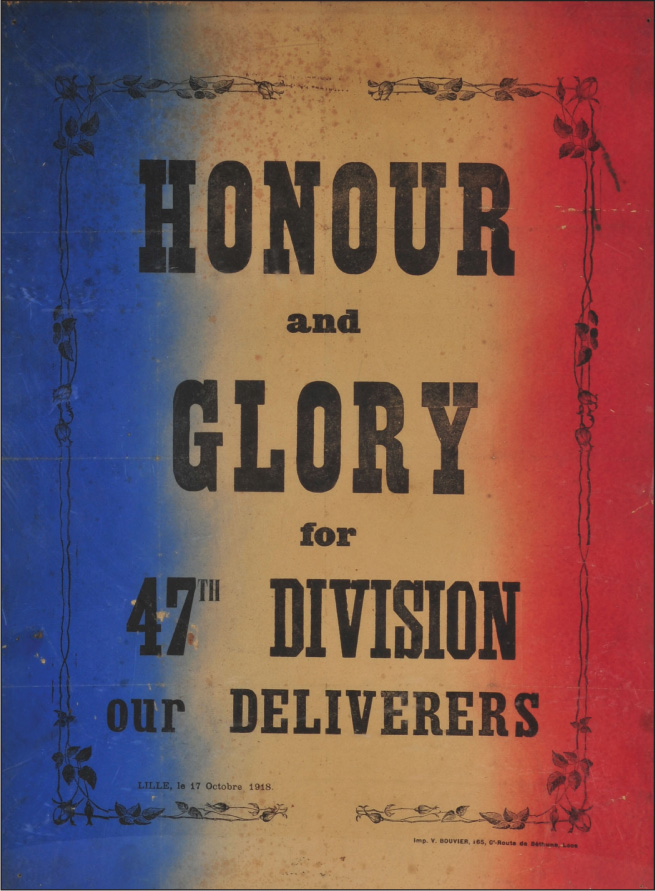

This simple poster was printed by V. Bouvier in Loos in 1918. Posters of this type appeared in their hundreds, as areas were gradually freed from German rule by advancing Allied troops. Few survived, and today there are only a few very rare examples of the genre of liberation posters.

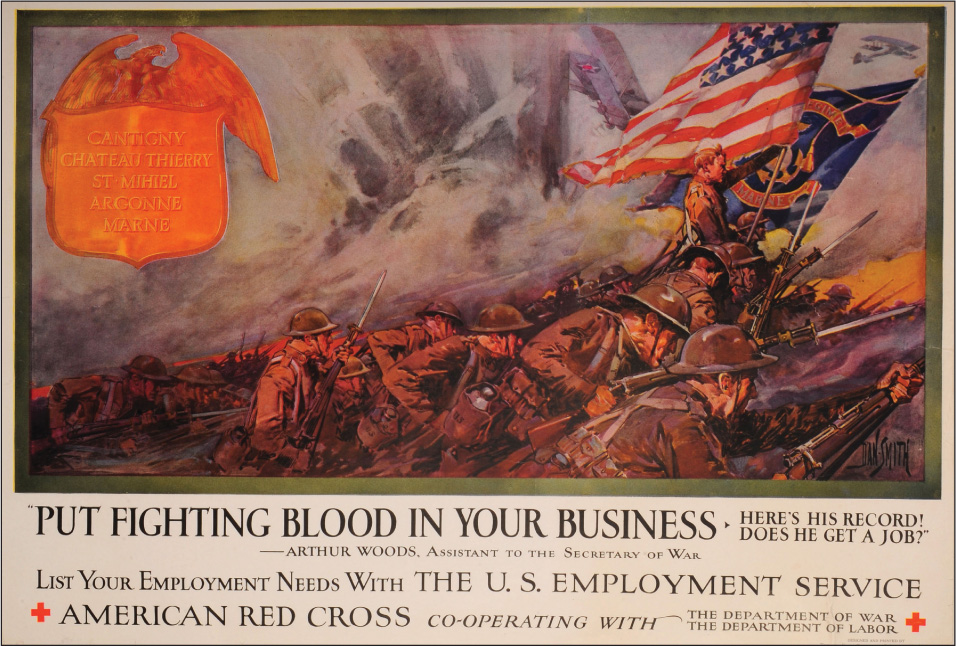

Not all posters were created to get men to enlist in the armed forces; this superb artwork by Dan Smith (1865–1934) was designed to help men find work after the fighting was done. A joint venture between the American Red Cross and the US Employment Service, it depicts the bravery of the US Marines as they fought their way towards victory, listing their battle honours, and it asks that the soldiers be given work on their return. The reality was that, despite government promises to the soldiers (Lloyd-George’s famous 1918 election speech promising a ‘land fit for heroes’ being a prime example), after 1918 tens of thousands of disillusioned ex-soldiers in Britain and the USA found themselves unwanted and unemployable as the war economies collapsed.

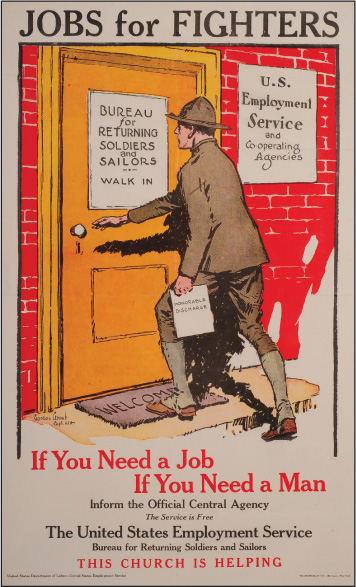

On a similar theme, an American soldier clutching his ‘honourable discharge’ certificate enters an employment exchange. This poster was produced in 1919 by the US Employment Service and was drawn by Grant Gordon (1875–1962). Although born in San Francisco, Gordon was sent to study at the Fife Academy in Scotland before returning to San Francisco in 1896. As an on-thespot war artist he witnessed first hand both the Boer War and the Mexican Revolution. His sketches were published in Harper’s Weekly, and the long voyage home by sailing ship started his fascination with marine subjects. Today he is regarded as the United States’ premier maritime artist.

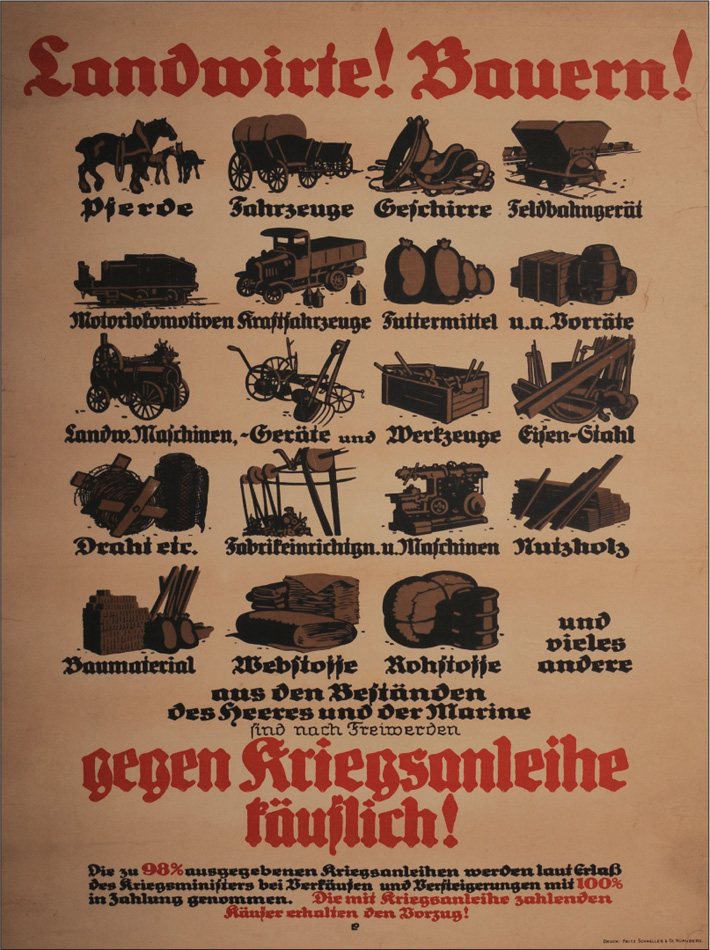

‘Countrymen! Farmers!’ After the war the immense stocks of equipment held by the army and navy were no longer needed. Like other nations, the Germans auctioned them off. In this case, they sold them against war bonds: buyers paying by this means would get priority and better prices. For the State, this was a way of reducing the incurred war debt. These financial problems would plague the young Weimar Republic, and the question of reparations would only come to a final close in 2011.

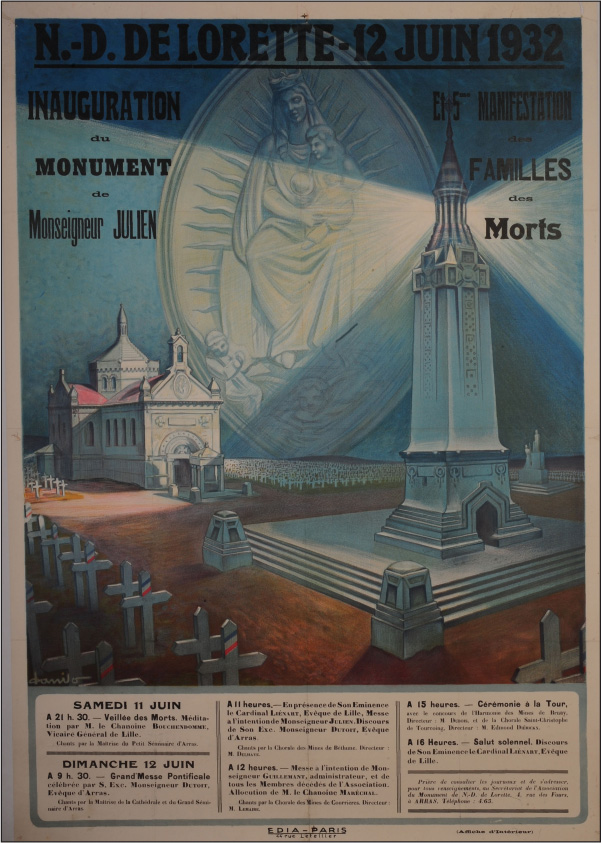

‘Our Lady of Lorette 12 June 1932. Inauguration of Bishop Julien’s monument and 5th march of the families of the dead.’ Grief and mourning dominated the postwar years. Notre Dame de Lorette, located on the hill-top overlooking the Artois battlefields, was to become the biggest French cemetery, containing the bodies of 42,000 soldiers. The 170ft-high lantern tower was inaugurated as a memorial in 1925 and the chapel was blessed in 1927 by Bishop Julien, who was instrumental in the rebuilding of the region. As so often happens, the mourning of individuals prompted the State to act in creating an official place and monument that are still actively involved in Remembrance today.

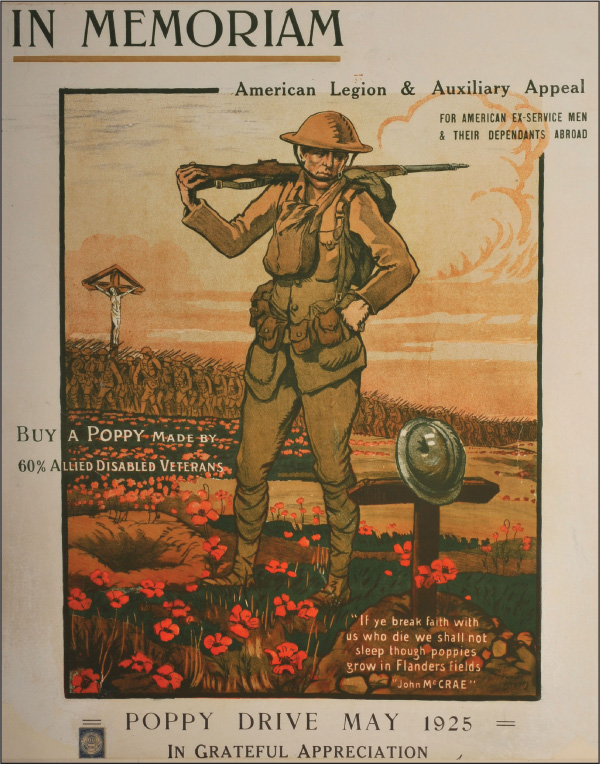

The seeds of the common poppy Papaver rhoeas can lay dormant for a hundred years, and a single plant can produce 60,000 seeds which burst into life when soil is disturbed. The shelling on the Western Front resulted in vast poppy fields, which soon became a potent symbol of the war. On 11 November 1921 the Royal British Legion held its first Poppy Day, a tradition that was briefly adopted by the United States. This British poster, with its famous lines from McCrae’s poem ‘In Flanders Fields’, was produced in 1925 to encourage donations to aid US ex-servicemen residing abroad. It was a little-known fact that after the war many hundred Americans still lived in England and other Commonwealth countries, and several hundred had elected to remain in France.

‘National Loan. General Society.’ Here the allegory of Victory, with a shell and a poppy at her feet, leads not soldiers but battalions of workers. The rebuilding of France is central to many postwar images, with posters insisting on the notion of rebirth by contrasting ruins and reconstruction. Here the land is being literally reconquered: the plough promises crops and fertile lands, and houses announce new comfort, while the train and factories show that a productive economy is already under way. In the warm colour of the sun, this poster offers a bright future to all – in particular to those who invest in the new loan.

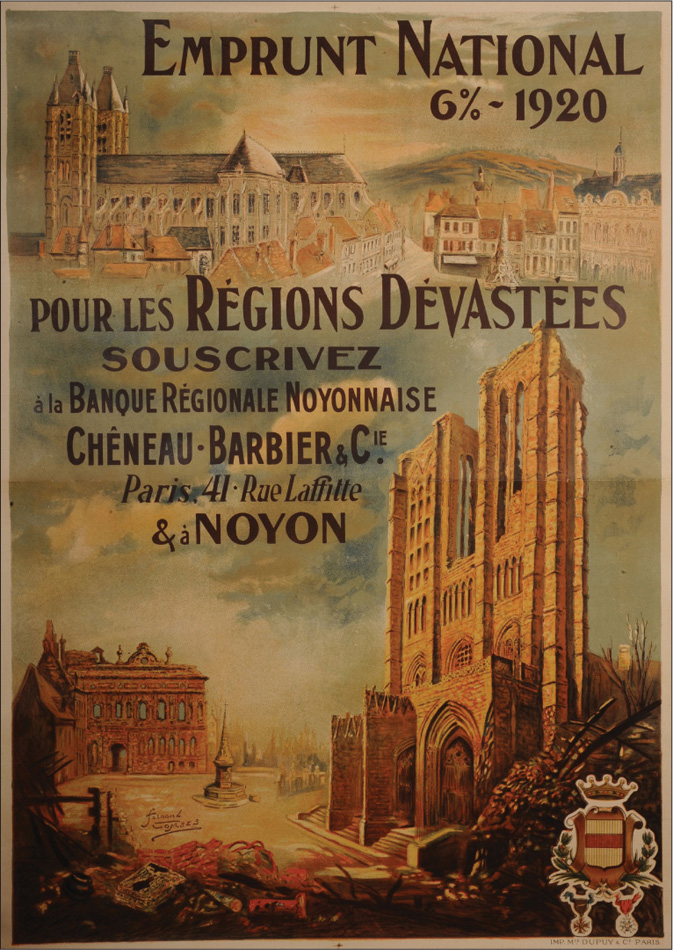

‘National Loan 6% – 1920 for the devastated regions, subscribe to the regional bank of Noyon County.’ Reparations from Germany were supposed to cover the costs of the conflict, and the success of the wartime loans made it all the more tempting for governments to launch new loan schemes after the war had ended. These loans were aimed at paying veterans’ pensions and rebuilding the country. To highlight this point, the poster compares prewar buildings with their condition in 1920.

‘City of Albert. 25 million loans in 500 Franc 6% bonds.’ The town of Albert was heavily shelled and severely damaged, and in 1915 the basilica itself was hit, leaving the statue of the Virgin Mary leaning down. A legend grew around it that the war would come to an end when the statue fell, but the basilica was completely destroyed by the British during the German spring offensive of 1918. More than three years later the leaning Virgin nevertheless still symbolised the devastation of the city, the reconstruction of which would go on until the early 1930s. For this reason, in 1920 two more national loans (and countless local ones) were needed for reconstruction.

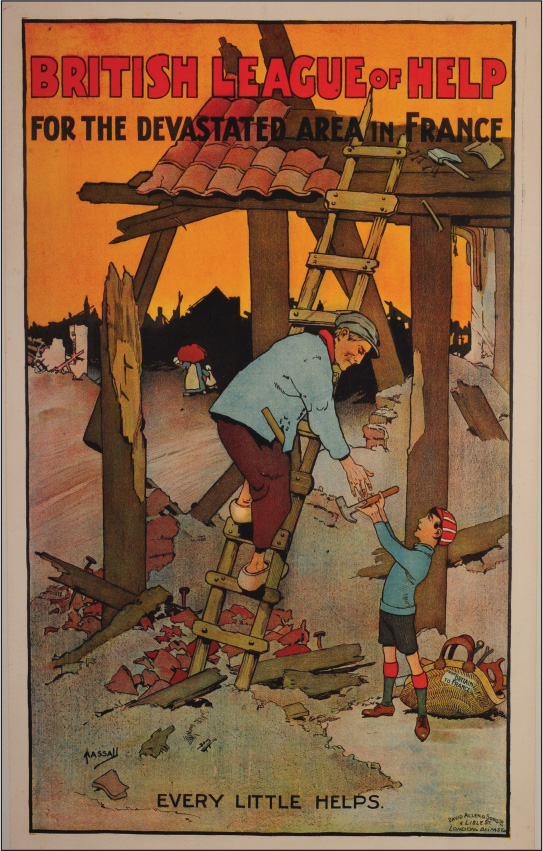

This British poster by John Hassall (1868–1948) from late 1918 illustrates the start of the reconstruction of the devastated areas of northern France with a rather forlorn attempt by a man and his son to re-tile a shattered house. In fact, some 1.5 million French civilians had been left homeless and such was the level of destruction that many villages were simply never rebuilt. Hassall was one of Britain’s premier illustrators and at his New Art School in Kensington had numbered Bert Thomas and Bruce Bairnsfather among his students. The Kodak Girl he created in 1910 was used by the company until the 1970s, but he has gained more lasting fame as the creator of the much-reproduced ‘Skegness is So Bracing’ poster.

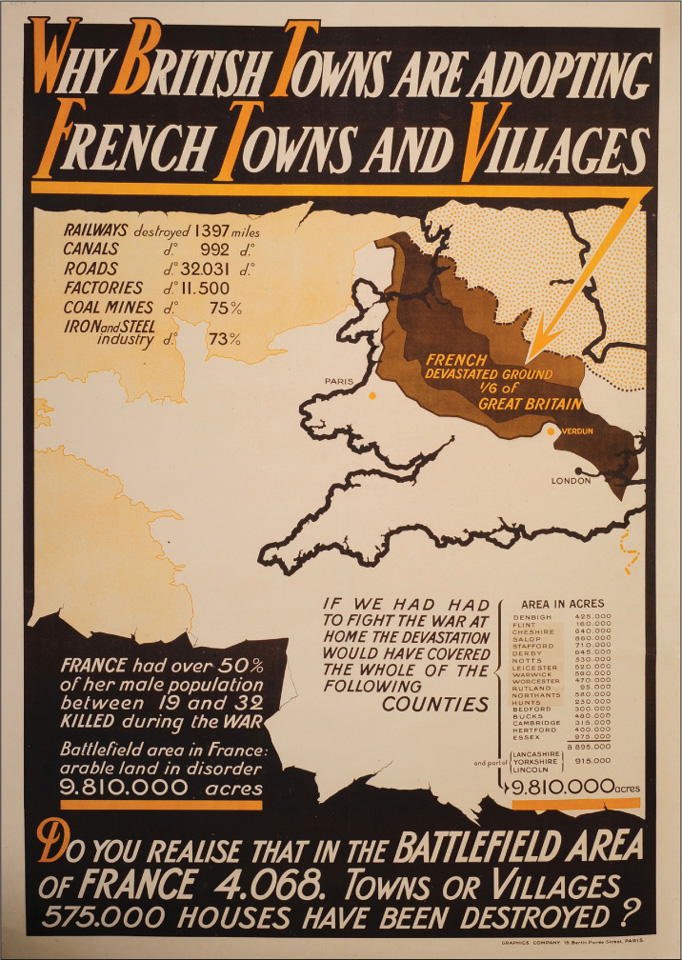

An illustration that is interesting more for the information it carries than its artwork, this 1919 poster is promoting the adoption of French towns by British cities to aid reconstruction. One reason for the slowness of rebuilding was simply the lack of men. France had lost 1,357,800 dead and 4,266,000 wounded, of whom 1.5 million were permanently maimed. These losses comprised some 73 per cent of the 8,410,000 men mobilised. Funds were sorely needed, but so too were men, and in farming regions free land and housing were offered to immigrants. Many thousands of displaced Belgian agricultural workers, as well as Czech and Polish miners, settled in northern France after the war.

‘Great “dressed-up, masked and travesty” ball given for the war victims by the veterans’ association.’ Calls for generosity did not all rely on making people feel guilty. This unusual poster seems to correspond to the idea of the ‘roaring twenties’. The French Poilu is represented as a boisterous party-goer. This entertaining event could probably only be depicted in this way because it was organised by veterans themselves. It must be added that the Poilus are included in a company of noblemen, literary figures (the long-nosed Cyrano de Bergerac) and glorious historic soldiers.

‘What we must lose. 20% of our productive land. 10% of our population. ⅓ of our coal production. ¼ of our bread and potato production. ⅘ of our iron ore. All our colonies and merchant ships.’ This summary of the Versailles Treaty barely exaggerates the facts. The treaty was denounced as a ‘Diktat’. But what shocked most Germans was the fact that they were held responsible for the war. For years criticising the Versailles Treaty would be the cornerstone of German politics.

‘Volunteers of all arms protect Berlin. Join the Reinhard Brigade.’ For Germany, the Great War ended in a revolution, sparked when sailors in Kiel mutinied against their officers. The unrest spread and soon German soviets had mushroomed throughout the country. The Kaiser abdicated on 9 November and fled to the Netherlands, and German officers reacted by organising unofficial ‘Free Corps’. These far-right paramilitary units fought the ‘Bolshevik danger’ inside and outside Germany, and soon became a threat to the young Weimar Republic. Many Free Corps members would become the link between Great War veterans and Nazi leaders. The Reinhard Brigade was instrumental in the crushing of the Spartakist (communist) uprising in Berlin in January 1919 and in the fighting against the Poles.

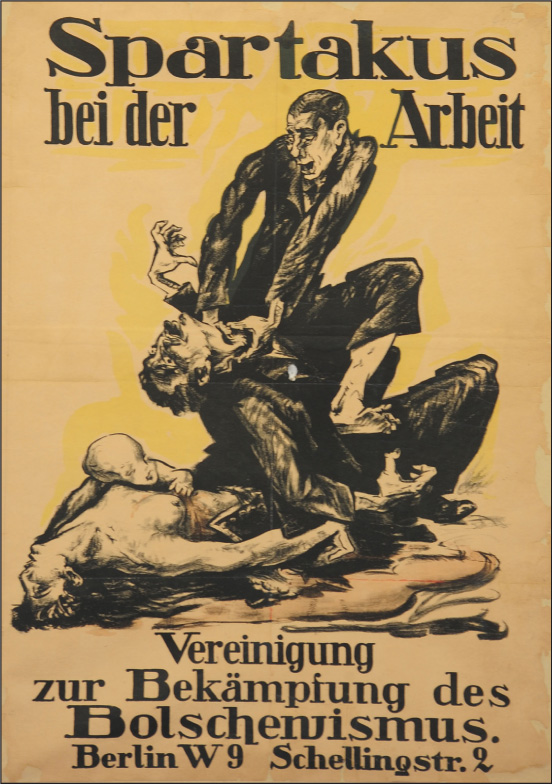

‘Spartakus at work.’ The ‘Union for fighting Bolshevism’ was the reaction of the German conservative upper middle-class, which feared that the November revolution would follow the Russian revolution and not only create a new democratic political system but also become a menace to their property. It started a costly poster campaign where Great War artists did not hesitate to use the most violent representations. The unflinching message systematically had the communist drawn as a depraved murderer or an inhuman beast. Thus, at the beginning of 1919 the new social-democratic republic was, surprisingly, helped by reactionary forces.

‘Bolshevism means the world drowned in blood.’ The wolf, as a savage beast, needed no explanation: predatory animals had long been used by all political sides as a metaphor for the enemy. The beastly representation was, in this case, financed by the ‘Union for fighting Bolshevism’. As is often the case with imagery spawned from fear, these posters were particularly violent and extreme. This imagery of total rejection left no room for compromise. It would subsequently be reemployed by the Nazis to characterise the ‘Eastern danger’.

‘The country is in danger. Great financial means are needed for protection in the East. Help now!’ Great War posters represented a breakthrough for political propaganda in Germany. The new images brought on a new radicalisation in society. The figure of the revolutionary foreigner (from Russia) dates back to the nineteenth century, when antidemocratic movements used the same iconography. Slavs were seen as a cruel, despotic race. These images were reinforced by the burnt land found after Russian retreats on the Eastern Front, and by the chaos of the Russian revolution. Fear of Cossack cruelty was still played on during the Cold War.

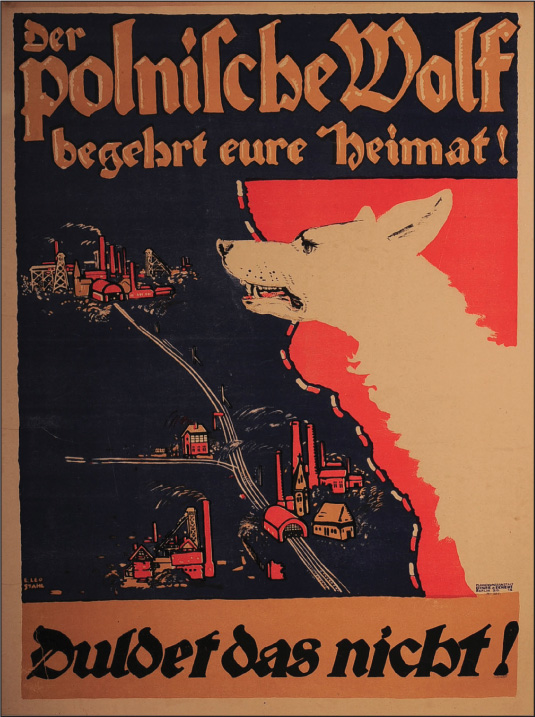

‘The Polish wolf covets your homeland. Do not tolerate it!’ As early as 1918 fighting broke out along the disputed border between Germany and the new Poland. In the east, many German towns were surrounded by Polish-dominated countryside. The fighting for Upper Silesia would continue until 1921. Even in 1926, when the international situation was more peaceful, Germany only officially recognised its western borders in the Locarno Treaties. The dehumanised menace contrasts with the wealthy industrial region.

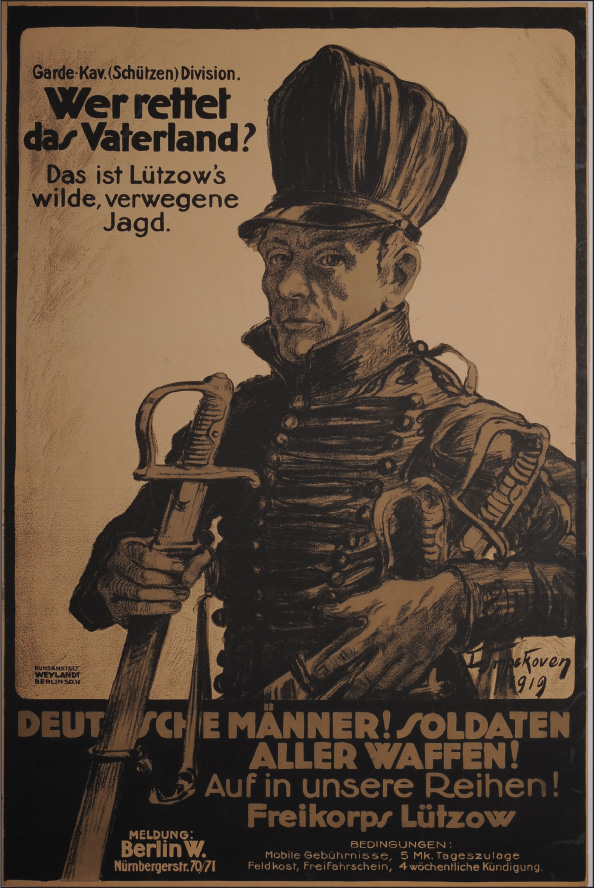

‘Who saves the Fatherland?’ Turning to a glorious, adventurous past was a way of erasing the painful defeat of the present. Ludwig Adolf Wilhelm von Lützow had organised a Free Corps during the Napoleonic wars. Though its military impact is still debated, the Black Troop that he raised was famous for its bravery and was immortalised in Theodor Körner’s poem ‘Lützow’s wild, daring hunt’, as mentioned on this poster. For all these romantic reasons, the Berlin-based Lützow Free Corps formed in 1919 by Major Hans von Lützow used the historic figure as a recruiting tool.

‘Comrade, help me! Against Bolshevism, the Polish danger and hunger, enlist immediately into the 31st Protection Division.’ This poster for a semi-official infantry division combines the main subjects of German concern in the immediate postwar period. Hunger was by no means solved by the armistice as the Allies continued to blockade ports until the peace treaty was signed. The new regime not only had to deal with communist uprisings throughout Germany but also faced the attempts of the newly reborn Poland to annex by force its neighbouring regions. These various dangers are depicted here in a typical beastly incarnation. The poster methodology of the Great War directly mirrored the new situation.

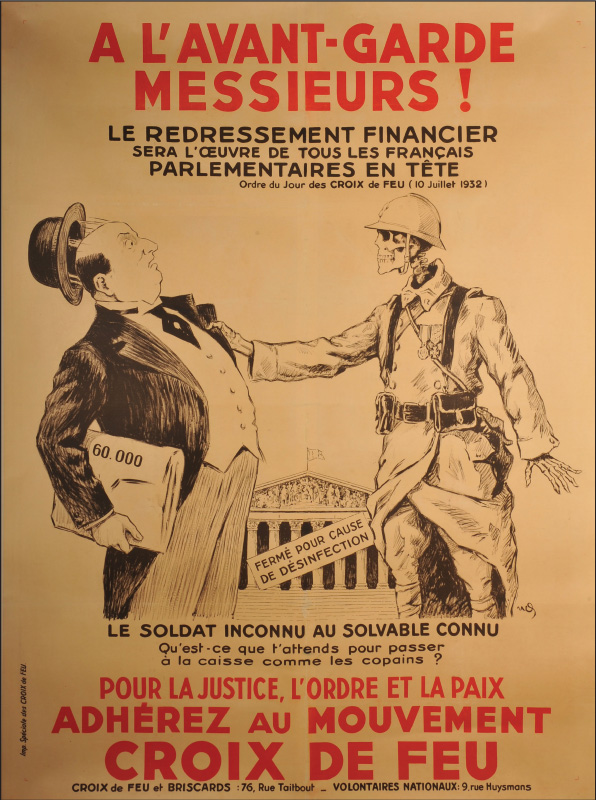

‘Forward March, Gentlemen!’ The Death’s Head became the badge of the Croix de Feu, a paramilitary group of French soldiers decorated for their bravery in battle. Led by Colonel De La Roque and relying on the so-called trench fraternity, it developed an anti-parliamentarian, authoritarian view. Though it did not actually march on Parliament during the 6 February 1934 demonstration, the Croix de Feu became the symbol of a potential Fascist takeover for the French left.

‘Comrades. Protect the German Republic! Enlist for the East!’ Though the Great War’s aftermath led to the rise of extremism and totalitarian regimes, democratic movements did not remain passive. The newly founded German Republic, with its political capital ultimately in Weimar, was based on a centre-left coalition, which replaced the old black, white and red imperial flag with the flag of the nineteenth-century German democratic movement. This official poster from Dresden, listing the improved material conditions for soldiers, aimed at creating a professional army so that the government would not have to depend upon the Free Corps.

‘11 May 1924 General Election. The result of wars. If you want to get rid of war, join the Socialist Party and vote for its candidates.’ Despite the many upheavals of the leftwing parties in France, prewar pacifist policies were again promoted. The Socialist Party contrasts here the bourgeois profiteer with the unemployed war veteran. The latter’s laurel-crowned helmet and medal are clearly visible on the wall above him. War is therefore denounced as an economic absurdity which impoverishes the majority.

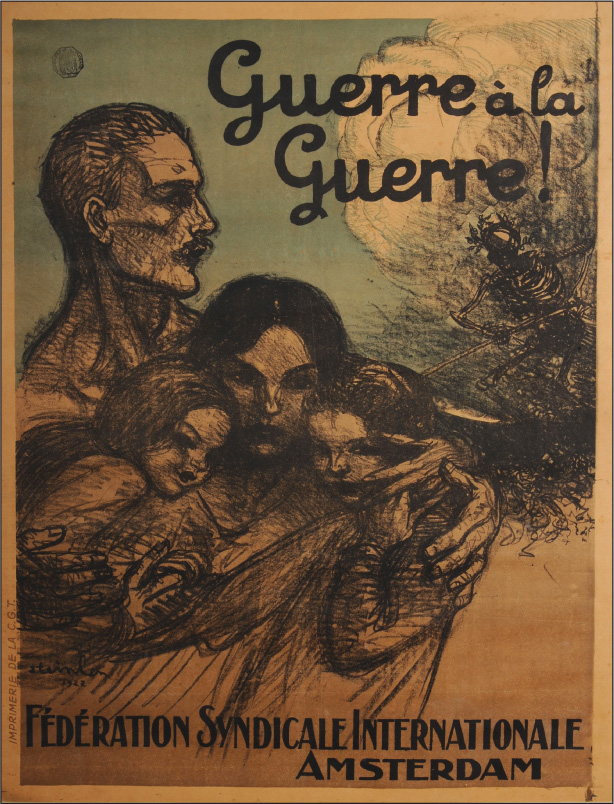

‘War on war!’ Théophile Steinlein (1895–1923) was one of the farleft’s most famous artists, and after the war he was close to the newly founded French Communist Party and the CGT trade union. A year before his death he produced an anti-war poster that did not reflect explicitly the communist vision of an imperial war based on class-warfare considerations. Rather, it appeals to a pacifist mood by showing a family protected by the father from a laurel-wreathed Death. The Grim Reaper is clearly the only winner in war.

‘Children. Don’t play at war. Parents, if you want your children to live, prepare the moral disarmament, ban war toys. International League of Peace Fighters (LICP).’ The Frenchman Victor Méric founded the LICP in 1931 and successfully attracted many intellectuals, including Stefan Zweig. Convinced that war was the product of poor education, the League put much of its effort into deconstructing all justification, glory or fascination for war. The notion of sacrifice for a cause was systematically replaced by one of meaningless death. Its extreme pacifism brought the number of members up to 10,000 in 1935 before fighting the Fascist regimes seemed unavoidable.

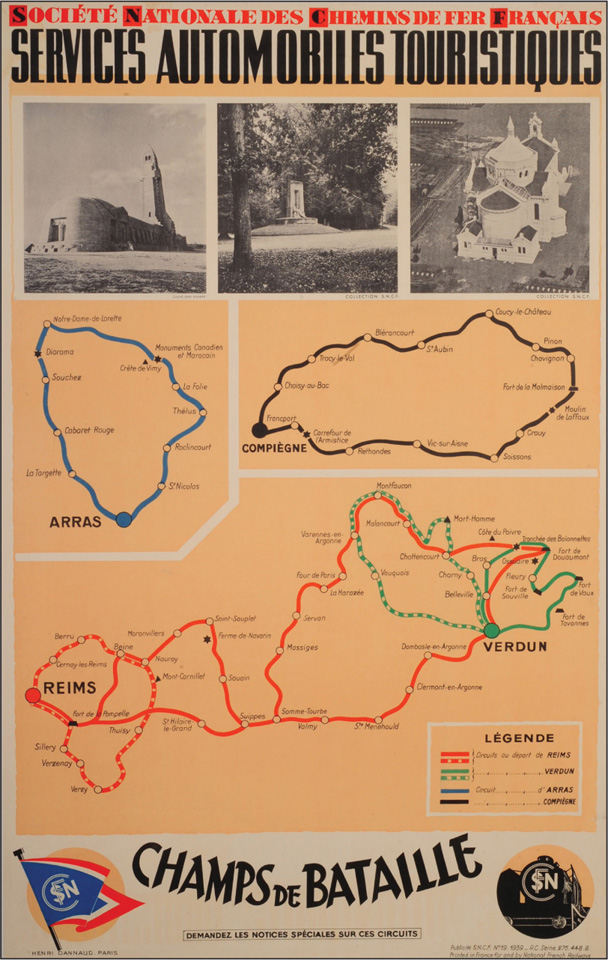

‘National Service of French Railroads. Tourist automobile service. Battlefields.’ As early as 1917 war tourism started in the ‘liberated regions’ after the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line. Families looking for the grave of a loved one visited the former battlefields, along with the simply curious. Tensions between pilgrims and tourists existed from the beginning. After the war numbers grew considerably. In 1929 2 million German visitors travelled to battlefields in France but their numbers were dwarfed by the massive pilgrimages of the Allied side. Still today, over 200,000 visitors (many coming from Great Britain or the Commonwealth) come annually to discover or rediscover the Somme battlefields.

A classic piece of imagery that carries no obvious message, this poster depicts a soldier of the 36th Ulster Division sitting in the splintered, moonlit remains of Thiepval Wood as crows wheel above. It is beautiful but has a slightly sinister overtone, and was commissioned from the artist Henri Grey to promote the ‘Northern France Railway Company’, presumably to encourage visitors and pilgrims to visit the old battlefields. Thiepval had been a particularly difficult objective to capture and was only overrun on 25 September 1916 after almost three months’ fighting. The Frenchman Henri Grey was a prolific poster artist, specialising in colourful advertisements, although little is now known of him.

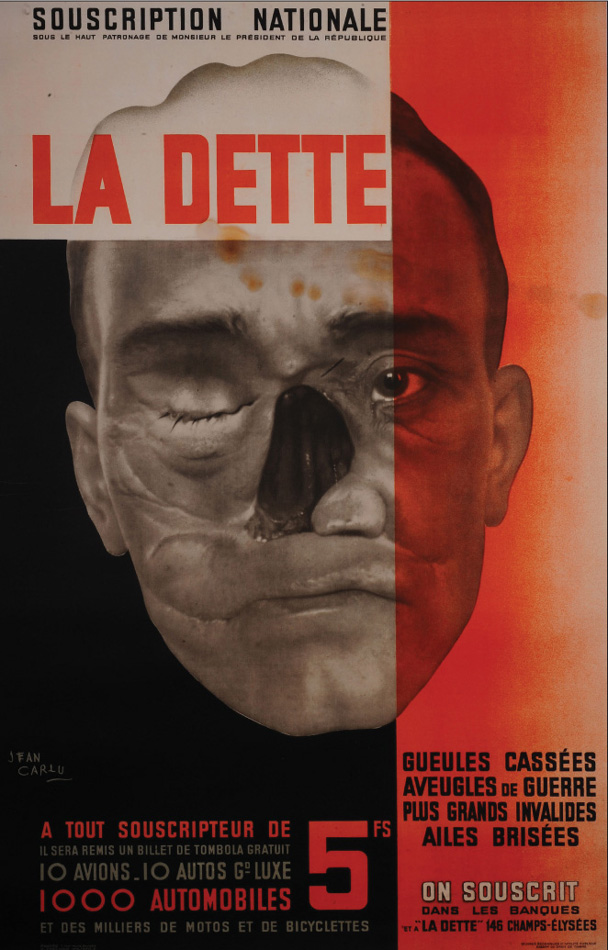

‘The debt. Broken faces, war blind, major invalids, broken wings.’ In 1931 the French ‘Broken Face’ association for facially disfigured war veterans started a raffle. Prizes included cars and even aeroplanes. The National Lottery was created in 1933, and until 2008 was a way of helping these disfigured men who lived in specialised homes similar to the Star & Garter in the United Kingdom. Jean Carlu innovated by using, for almost the first time, a photomontage approach. The reality of the suffering cannot be escaped: the direct gaze insisted that there was a moral debt all civilians had to pay towards wounded veterans.

‘History starts again. 1914: I want peace. 1934: I want peace.’ The probable victory of the left in France encouraged nationalists to denounce pacifists as idealists. André Galland (1886–1965) here creates a clever parallel in order to present Hitler as the new Kaiser. Germany, and Wilhelm II personally, were still widely considered as responsible for the Great War. Though the poster doesn’t mention the elections, it implies that the left-wing candidates would be too weak against an aggressive Germany: the Nazis had been the most outspoken group in their refusal to accept the 1918 defeat. This parallel, however, also shows that the French right did not understand what gave Nazism its unique character.

‘1918–1943.’ The German revolution and the proclamation of the Republic on 9 November 1918 were always associated by the Nazis with military defeat. They considered that the army had been ‘stabbed in the back’ by the Jews and the Bolsheviks. Twenty-five years after the events, this poster focuses on the figure of the German soldier, ambiguously drawn to represent both world wars, as the bastion against chaos and as a model of the new society. Even after Stalingrad, every German child was supposed to learn about the 1916 Battle of the Somme in order to understand the iron-willed German soldier who survived it and who went on to build the new Germany. The Great War remained a role model.

‘Our advance in the east. Facts against lies. Moscow and London have lied constantly about Soviet successes and German defeats or about our operations’ slightest set-backs. Here is our answer: in 1915, we stood there six weeks after the beginning of the spring offensive. We stood there in 1917 at the beginning of the armistice negotiations. And here we stand six weeks after the beginning of the Eastern campaign.’ The reconquest of the Eastern ‘savage’ lands that belonged to the German ‘vital space’ was considered by the Nazis as a logical outcome of the Great War. Comparing Great War front lines with the first six months of Operation Barbarossa seems once again to go back to traditional propaganda: it puts the campaign into perspective but conveniently ignores that the 1917 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk allowed German troops to occupy all of the Ukraine.

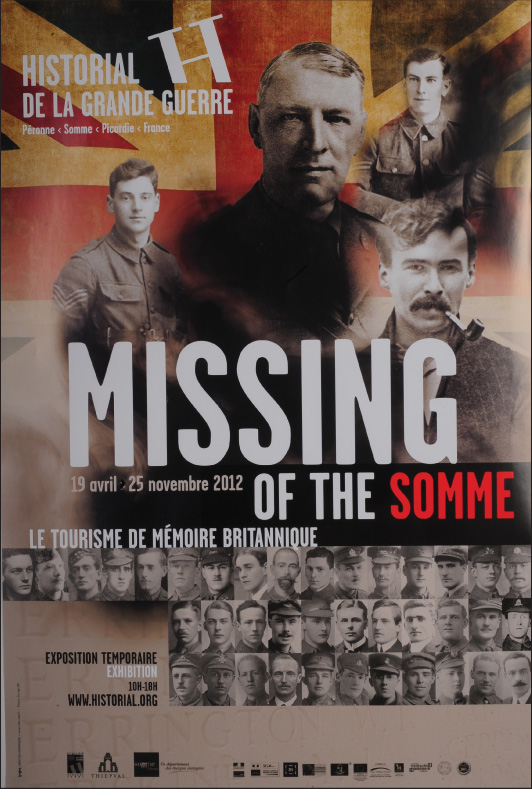

The Great War remains a defining moment of our history. Remembrance is still strong today and takes on many shapes. Armistice Day still has a powerful meaning in both Britain and France. Visitors on the battlefields try to understand what happened and focus increasingly on the war experience of the men. Some see these men as titans who fought for our freedom, others would rather insist on today’s attitude of reconciliation and peace. In all these cases, events and activities (ranging from official ceremonies to private tours and battlefield walking) still mark anniversaries and other dates. For the 80th anniversary of the Thiepval monument, the Historial Museum decided to devote a whole exhibition to recounting the lives of the British soldiers who died on the Somme and have no known grave. It illustrates the ways they have been remembered since then. Also by showing the faces of these individuals, the exhibition’s poster reminds us that they are missing but not forgotten . . .