Learning Objectives

This chapter completes our journey through the selling process by examining closing the sale and following-up to enhance customer relationships. Closing is a natural progression of the process. Because we are building toward win-win solutions with customers, closing simply connotes that both parties recognize the value-added of doing business with one another. Postsale follow-up presents a marvelous opportunity to add even more value to clients through problem solving and service.

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- • Define closing and explain how closing fits into the Model for Contemporary Selling.

- • Understand different closing methods and provide examples of each.

- • Discuss the concept of rejection and ways to deal with it.

- • Identify various verbal and nonverbal buying signals.

- • Know when to trial close.

- • Recognize and avoid common closing mistakes.

- • Explain aspects of follow-up that enhance customer relationships.

- • Understand the sales manager’s role in closing the sale and follow-up.

Closing the sale means obtaining a commitment from the prospect or customer to make a purchase. Even long-time customers still need to be closed on specific orders or transactions. Also, as you learned in chapter 7, a salesperson should always enter a call with specific goals for that call. Closing denotes the achievement of those sales call goals.

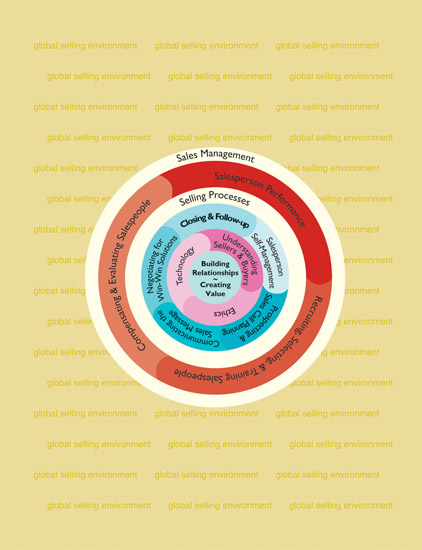

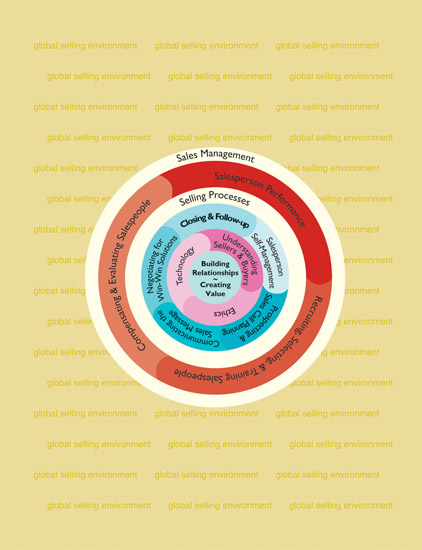

Closing the sale should not be viewed as a discrete event that takes place at the end of a sales call. Such a perspective leads to much anxiety on the part of perfectly capable salespeople by focusing on a single element in developing the client relationship. Chapter 1 introduced the concept of closing the sale in the context of our overall Model for Contemporary Selling:

The rapport, trust, and mutual respect inherent in a long-term buyer–seller relationship can take some of the pressure off the “close” portion of the sales process. In theory, this is because the seller and buyer have been openly communicating throughout the process about mutual goals they would like to see fulfilled within the context of their relationship. Because the key value added is not price but rather other aspects of the product or service, the negotiation should not get hung up on price as an objection. Thus closing becomes a natural part of the communication process. (Note that in many transaction selling models, the closing step is feared by many salespeople—as well as buyers—because of its awkwardness and win-lose connotation.)

This chapter is designed to allay any fear you may have about closing the sale. Salespeople must be able to “pull the trigger” and close the deal, else they will never do any business. So relax, read on, and by the end of the chapter we believe you will agree that successfully closing sales in an environment where the goal is to build relationships and create value both for your firm and your customers is quite achievable.

The components of successful selling you have learned so far throughout this book liberate you from the need to use clever, tricky, and manipulative closing approaches with your prospects and customers. Note that our guiding Model for Contemporary Selling is not linear. That is, it doesn’t show “steps” of selling progressing one after another in order. This is because selling usually is decidedly nonlinear and the various components of the selling process take place simultaneously, always focused on building relationships and creating value. The circular layout of our model symbolically represents this approach.

Nowhere in the selling process does understanding the nature of the Model for Contemporary Selling become more relevant than in closing the sale. Closing as a selling function is actually appropriate at any point in the selling process—not just at the end of a lengthy sales presentation. In this chapter, we advocate learning different approaches to closing, because knowing different ways to communicate to buyers the need to gain commitment to the goals of the sales call is a fundamental skill in seller–buyer communication. However, we also strongly advocate that these closing skills be used at the appropriate point in the dialogue with the customer—not just at the end. The salesperson must watch for buying signals, verbal and nonverbal cues that the customer is ready to make a commitment to purchase.

If a salesperson has done the job well on the tasks described so far in this book—understanding the buyer, creating and communicating value, behaving ethically, using information for prospecting and sales call planning, communicating the sales message effectively, and negotiating for win-win solutions—why should the close be anything other than a natural progression of the dialogue with the customer? That’s the most healthy and constructive way to look at the task of closing the sale—and it focuses on doing a great job of the whole selling process, not just the “dreaded close” at the end.

What you learned in chapter 8 about always working to find win-win solutions has particular relevance in closing the sale. In their popular book Getting to Yes, Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton frame it this way: The core of selling is negotiation. The salesperson has goals and a perspective; the customer has goals and a perspective of his or her own. The art of selling is finding the common ground where both parties can win by developing a mutually beneficial business relationship. To do so, sellers must have a high level of empathy in dealing with their prospects and customers. An empathetic salesperson identifies with and understands the buyer’s situation, feelings, and motives. Also, they must set goals for the sales call that are consistent with the customers’ needs.1 If both parties win from doing business together, surely this has been communicated throughout the dialogue between seller and buyer. Points of agreement have already been established. The idea that a win-win solution would somehow come as a revelation only at the end of the dialogue does not match the spirit or the process of relationship selling.

To summarize:

- • Closing is a natural part of the selling process.

- • The process is rarely linear. The close need not happen at the end of a lengthy sales presentation.

- • Salespeople must watch for buying signals any time during the seller–buyer dialogue and act on those signals by closing then.

- • It is important to take the buyer’s perspective in closing, working toward win-win solutions for both parties by communicating and delivering value to the customer and to your own company.

- • Based on the above, salespeople must understand and be able to use different approaches to closing.

There are many ways to close the sale. No salesperson can rely on just one or a few of them. Successful salespeople learn how and when to use many different approaches to closing so they can apply each appropriately in different situations. Just as you learned in chapter 7 that memorized or “canned” sales presentations have major limitations, canned approaches to closing do not give you the ability to adapt to a particular sales situation. It is critically important that any closing technique be customized to the particular buyer and situation. Like many aspects of selling, doing this successfully takes practice and improves over time.

A common theme of sales success that was discussed in chapter 7 is the need for salespeople to develop and practice active listening skills. In the context of closing the sale, active listening refers to carefully monitoring the dialogue with the customer, watching for buying signals, and then picking just the right time to close. Only when you listen actively will the buyer have the chance to register verbal and nonverbal buying signals that tell you it’s time to close.

Another closing tool is silence. When you close, you have just put the ball into the prospect’s court. It is now time to sit back, be quiet, and let the customer talk. Research indicates that effective use of silence in closing separates high-performing salespeople from the other kind.2 Make no mistake, silence can be challenging to use in a sales call. If you bounce the ball to the prospect through a close and the prospect doesn’t pick it up and run with it by either providing objections or making a commitment to buy, seconds of silence can seem like minutes (or hours!). However, try to resist jumping in. Give the prospect the maximum leeway to respond to your close.

The seven closing methods here are a sampling of some of the most used approaches. Examples are provided for each. However, remember that good salespeople adapt closing techniques to particular buyers and particular selling situations.

In a way, salespeople always assume they are going to close. Otherwise, they would be hard pressed to justify time spent on a prospect. The assumptive close allows the salesperson to verbalize this assumption to see if it is correct. Examples:

- • “I can ship it to you on Monday. I’ll go ahead and schedule that.”

- • “Let’s get this paperwork filled out so we can get the order into the system.”

- • “You need Model 455 to meet your specifications. I’ll call and reserve one for you.”

Obviously, you are looking for the buyer to just naturally move along with your assumption. If he or she doesn’t, as with any close you will likely uncover some additional objections you need to deal with.

Several of the other closing methods are assumptive in nature. In fact, it is generally favorable to handle all communication with the prospect with the attitude that he or she will ultimately buy. This creates an atmosphere in the sales call that supports the concept of moving to win-win solutions.

In the minor point close, the salesperson focuses the buyer on a small element of the decision. The idea is that agreeing on something small reflects commitment to the purchase, and the salesperson can move forward with the deal. Examples:

- • “What color do you prefer?”

- • “Do you want to use our special credit terms?”

- • “When would you like our technical crew to do the installation?”

Usually the alternative choice close also focuses the buyer on deciding relatively minor points. This approach simply adds the twist of giving the prospect options (neither of which is not to buy at all). Focus on making the choice between viable options—options the prospect is most likely to accept. Examples:

- • “Which works best for your application, Model 22 or Model 35?”

- • “Would you like this delivered tomorrow, or would Monday be better?”

- • “Do you want it with or without the service agreement?”

This approach is most straightforward. With the direct close, you simply ask for the order. Although simple, this close can be highly effective when you get strong buying signals and your buyer seems to be a straight shooter. Such buyers often appreciate the direct approach. Examples:

- • “It sounds to me as though you are ready to make the buy. Let’s get the order into the system.”

- • “If there are no more questions I can answer, I would sure like us to do business today. What do you say?”

Throughout the sales process, you and the buyer have (we hope) found common ground for agreement on a variety of points. The summary-of-benefits close is a relatively formal way to close by going back over some or all of the benefits accepted, reminding the buyer why those benefits are important, and then asking a direct closing question (or perhaps ending with a choice or some other method). Example:

- • “Ms. Buyer, we’ve agreed that our product will substantially upgrade your technical capabilities, allow you to attract new business, and all the while save you money over your current system, isn’t that right? (Buyer agrees.) Given your timetable for implementation, let’s go ahead and place the order for one of our systems today. We can have it delivered in two weeks and I will have my service technicians out then to begin training your staff on using the system.” (Silence. Wait for response.)

The balance sheet close, also sometimes called the t-account close, gets the salesperson directly involved in helping the prospect see the pros and cons of placing the order. In front of the customer, take a piece of paper and write the headings “Reasons for Buying” on the top left and “Remaining Questions” on the top right. (Don’t put the word “Objections” on the top right; it sounds too negative.) Your job is to summarize the benefits accepted in the left column and use the right column to find out what is holding the prospect back from buying. You might set up the exercise like this:

- • “Mr. Buyer, let’s take a few minutes to list out and summarize the reasons this purchase makes sense for you, and also list any remaining questions you may have. This will help us make the right decision.” (Pull out paper. Have a dialogue with the buyer to develop the points. When finished, use an appropriate closing method.)

The buy-now close, also sometimes referred to as the impending-event close or standing-room-only close, creates a sense of urgency with the buyer that, if he or she doesn’t act today, something valuable will very likely be lost. In professional selling, manipulative closing techniques are strictly taboo, so you have to be honest here. That is, the reasons you set forth why the buyer will benefit if he or she doesn’t hesitate must be real. Examples:

- • “We have a price increase on this product effective in two weeks. Orders placed today can be guaranteed to ship at the current price.”

- • “My company is running a special this week. This product is currently 20 percent off the regular price.”

- • “Orders placed by Thursday receive an extra 30 days before the invoice is due.”

- • “I’m almost out of stock on this product in our warehouse.”

There are many other forms of closing. In his book The Art of Closing Any Deal, James W. Pickens lists no fewer than 24 techniques he calls “the 24 greatest closes on earth.”3 However, not every closing technique you may read about is really appropriate. The above seven approaches are tried and true ways to move your buyer to commitment without resorting to unnecessarily tricky or questionable tactics. As a salesperson you will become more and more comfortable with using the different closing methods as you have the opportunity to practice them.

In chapter 6 you learned that an important aspect of prospecting is qualifying the prospect and the better job a salesperson does of qualifying prospects, the more likely those prospects will eventually turn into customers. Prospecting is in many ways a numbers game. The more leads you can qualify as prospects, the more customers you develop, and ultimately the more sales you close.

Many times a salesperson can do everything right and still not get a customer to close a deal. It is important for anyone in the sales profession to reflect on this fact and to understand at a deep human level that failing to get an order or close a deal is not personal rejection. A salesperson’s measure of accomplishment and self-worth should not be controlled by what someone else does or fails to do. Nobody can make you feel inferior without your permission!

It is one thing to be disappointed by not getting an order or closing a particular sale, and it is perfectly reasonable (and wise) to step back and analyze what might have caused this outcome and what you might do differently next time. This is simply learning and growing professionally. But successful salespeople never construe such business decisions by customers as personal rejection. They maintain their positive attitude about their job, their company, and their products and move on to the next customer.

Tom Reilly, a well-known authority on professional selling, developed five tactics for dealing with rejection, which he has used in successfully training salespeople for many years:

- Remind yourself of the difference between self-worth and performance. Never equate your worth as a human being with your success or failure as a salesperson.

- Engage in positive self-talk. Separate your ego from the sale. The prospect is not attacking you personally. Say to yourself, “This prospect doesn’t really even know me as a person. The refusal to buy cannot have anything to do with me as a person.”

- Don’t automatically assume that you are the problem. The prospect may be an intimidating, self-serving individual with some deep personal problems that cause the behavior you see. The prospect may be just having a bad day or may be like that all the time. You are not to blame for any of these possibilities.

- Positively anticipate the possibility of rejection and it will not overwhelm you. Expect it, but don’t create it. That is, think in advance what your response to rejection will be if it occurs. (Note: This does not conflict with an assumptive close approach.)

- Consider the possibility that not buying is a rational decision because of underlying reasons. Possible reasons are bad timing, shared decision making, or budget constraints that truly do prevent purchase. The prospect may not feel comfortable revealing these reasons to you.4

The preparation you learned in chapter 8 for anticipating and handling buyers’ objections will help buffer you against taking rejection personally. If you do a great job during the preapproach of researching reasons a customer might not buy and then planning appropriate responses for dealing with the objections, at the end of the day if the customer does not buy you can look at yourself in the mirror and say, “I did everything I could.” This is a sign of professionalism in selling.

Excellence in call preparation yields a confidence and professionalism that cannot be equaled. This is why sales executives often call the preapproach the single most important stage in the selling process. (Interesting, isn’t it, how this runs counter to the stereotype that the most important step is the close?) If, despite your preparation and presentation, the customer still doesn’t buy, know when to pack up graciously and leave the door open to sell to this client another day.

Books on successful closing agree that a critical determinant of whether or not a salesperson closes customers is attitude.5 Attitude represents the salesperson’s state of mind or feeling with regard to a person or thing. Everything else being equal, salespeople who believe in themselves and their product or service, show confidence, exhibit honest enthusiasm, and display tenacity (sticking with a task even through difficulty and adversity) will close more business than those who don’t. Attitude is infectious. Customers pick up on a salesperson’s attitude and outlook on life right away.

In a survey 215 sales managers across a wide range of industries were asked which success factors were the most important in their salespeople. Tenacity (sticking with a task/not giving up) ranked fourth out of over 50 key success factors.6 Successful salespeople are successful in large measure because they don’t give up easily. They stick with the process of developing customer relationships and moving customers to closing the sale. They aren’t distracted from this core mission of selling, and they don’t feel rejected when they don’t make a sale.

One important way to approach closing involves envisioning a successful outcome with the buyer. Sit back and mentally rehearse how a positive outcome might unfold. Think about all the steps needed to close the sale. This exercise helps solidify the road map toward closing and also feeds your positive attitude and confidence before you actually engage in the close.

As we mentioned, a close does not necessarily happen at the very end of a presentation. It can happen any time. The timing is driven by the buyer’s readiness to commit—not the salesperson’s need to cover a certain amount of material, present all the available features and benefits, or make it to the end of the presentation. Many salespeople, especially new ones, experience problems in closing because they ignore or are insensitive to buying signals, those verbal and nonverbal cues that the customer is ready to make a commitment to purchase.

A buyer may not come right out and say “I’m ready to buy,” at least not in those words. However, salespeople should look out for the following verbal signals, which essentially communicate the same message.

- • Giving positive feedback. The most overt buying signal is a positive comment or comments from the buyer about some aspect of your product. Or the buyer may reinforce something you have said. Examples:

- • “I like the new features you described.”

- • “Those extended credit terms really help me out.”

- • “You certainly are right that our current vendor can’t do that.”

- • Asking questions. When buyers become more engaged, they tend to ask more questions. Buyer questions come in many types, and not all signal a readiness to buy. But watch for questions that seem to open the door to close. Examples:

- • “When will it be available to ship?”

- • “What colors does it come in?”

- • “How much is it?” (Note: A price question may be a signal to close, or it may represent the beginning of an objection.)

- • “Can you explain your service agreement?”

- • Seeking other opinions. Buyers usually don’t ask for opinions about your product or company unless they are seriously considering purchase. This may involve someone else in their company, or it may involve asking you for references or even your own opinion about you versus the competition. Examples:

- • “Let me get Bob from our engineering department in to look at your specs.”

- • “Who are some other firms that have bought your product recently?”

- • “Give me your honest opinion about how your product stacks up against your competitors.”

- • Providing purchase requirements. Watch for the point where a buyer begins to become very specific about his or her needs. Often these relate to relatively minor points, not the key attributes of your product or company. This signals acceptance of the major points. Examples:

- • “My orders must be split among four warehouses.”

- • “The only way I can change vendors is if you are willing to train my people to use your equipment.”

As you learned in chapter 7 on communicating the sales message, often nonverbal communication tells as much or more about the buyer’s readiness to buy as words. Watch closely for nonverbal signals that indicate it’s time to close.

- • The buyer is relaxed, friendly, and open. If the buyer moves to this mode during the call, it likely signals he or she is comfortable with what you are selling.

- • The buyer brings out paperwork to consummate the purchase. A purchase order, sales contract, or other form is a sure signal to close.

- • The buyer exhibits positive gestures or expressions. Head nodding, leaning forward in a chair, coming around the desk to get a better look at a sample, significant eye contact, and similar nonverbal signals denote interest and potential commitment to the purchase.

- • The buyer picks up your sample and tests it or picks up and examines your literature. The more involved your customer is in your presentation, the more likely he or she is ready for a close.

When you detect one or more buying signals, it’s time to engage in a trial close. “Trial” suggests that the buyer may or may not actually be ready to commit. A trial close can involve any of the closing methods discussed earlier. It may simply entail asking the buyer’s opinion about something. Often a trial close elicits a negative response from the buyer because he or she still has some objections you must overcome. By nature, a trial close can be used at any time during the sales process. In fact, if you walk into a sales call and get a strong buying signal immediately, go ahead and do a trial close. If the customer commits, that’s great. Never feel compelled to deliver a presentation to a buyer who is already sold! A trial close that works becomes the close.

You have already learned that closing the sale should not be viewed as an end in and of itself but rather as a natural part of the communication process. Over the long run, there will always be some orders you don’t get and some deals you don’t close. Avoiding a number of potential problems in closing will improve your success. The following are some classic closing errors.

- • Harboring a bad attitude. We established earlier that salespeople who believe in themselves and the product, show confidence, exhibit honest enthusiasm, and display tenacity will close more business than those with a different attitude. A positive approach to life is infectious and carries over to your relationships with customers.

- • Failure to conduct an effective preapproach. The preapproach stage is where you do the advanced research and planning needed to arm yourself with the knowledge to give the sales presentation, handle objections, and ultimately provide win-win solutions to customers. This “behind the scenes” part of selling is very important, and failure to properly plan for the sales call usually leads to poor results in closing. Well-prepared salespeople exude confidence; ill-prepared salespeople come across as, well, ill prepared.

- • Talking instead of listening. Listening is a key to understanding your buyer, getting to know his or her needs, uncovering objections, catching buying signals, and knowing when to trial close.

- • Using a “one size fits all” approach to closing. Closing methods must be carefully selected and customized to fit a particular buyer and buying situation. You certainly do not want to come across as a “closing robot” that uses the same techniques every time. Practice and experience will raise your comfort level in applying multiple closing methods to different situations.

- • Fear of closing/failure to close altogether. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, our hope is that by now you understand that asking for the sale is a natural part of the sales process when the focus is on building relationships and creating value. Any lingering fears about “pulling the trigger” to close the sale must be overcome in order to be a successful salesperson.

- • Uncertainty about what to do after the close. Sometimes salespeople will hang around and keep talking about the sale after the buyer has already committed. Would you believe that this behavior can talk a buyer out of a sale? It’s true! Once commitment is received, it’s fine to firm up details (delivery, timing, support staff, etc.). But never linger and postmortem the sale with the buyer.

At the end of this chapter is an Appendix, “Checklist for Using Effective Closing Skills.” Its extensive set of questions will help you identify what aspects of your closing skills are going well and what areas need more work. Especially for new salespeople, this checklist provides considerable insight into the complexity of issues in closing sales and is a source of ideas for use in closing.

Ethical Dilemma provides an interesting closing situation for your consideration.

In chapter 3 on value creation in buyer–seller relationships, many foundation issues were developed that lead to long-term relationships with customers. Central to nurturing these relationships are how the sales organization creates value for customers and how salespeople communicate that value proposition through actions and words. One of the most important ways to add value is through excellent service after closing the sale, often referred to as follow-up.

During this follow-up, the various dimensions of service quality described in chapter 3 really come into play. Recapping, those are:

- • Reliability. Providing service in a consistent, accurate, and dependable way.

- • Responsiveness. Readiness and willingness to help customers and provide service.

- • Assurance. Conveyance of trust and confidence the company will back up the service with a guarantee.

- • Empathy. Caring, individualized attention to customers.

- • Tangibles. The physical appearance of the service provider’s business, website, marketing communication materials, and the like.7

The above descriptors of good service refer not only to salespeople but also to their whole organization. Often salespeople rely heavily on support people to aid in postsale service. Customer care groups, call centers, technicians, and many others frequently represent a firm during the follow-up process. Sometimes these after-sale service functions are even outsourced and offshored.8 But no matter who else has contact with your customer, ultimately you—the client’s primary salesperson—are the person your customer views as the main representative of your firm. So you must understand and involve yourself directly in follow-up activities with customers.9

Ethical Dilemma

Who will Place the Order?

Jeff Hill of Southeast Distributors has a decision to make and not much time to make it. As Senior Account Manager for the Ronbev Technologies account, Jeff has a very good relationship with Ron Yokum, CEO and founder of Ronbev. In the four years since Jeff began managing the account, sales have increased 50 percent.

Ronbev has been a customer of Southeast for more than six years and the two companies have a close working relationship. Several years ago (after much hard work on Jeff’s part), Ron signed an agreement to make Southeast his exclusive supplier, thereby ensuring price stability and enhanced service. Neither Southeast nor Ronbev has been disappointed in the relationship.

Despite the strong relationship between the two companies, Ron (CEO) and Hugh Jacoby (Head of Purchasing) insist that they personally initiate every order. While overall sales are worked out in strategic planning meetings every year, the configuration of each order and specific characteristics of product size, quantity, and delivery dates vary a great deal. As a result, Ron feels it is important for either Hugh or himself to sign off on every order to be sure it meets Ronbev’s needs. Jeff often sits in on the strategic planning meetings and knows Ronbev’s purchasing patterns quite well.

Today he sits in his office considering a difficult decision. It’s the last day of the month and he is reviewing the Ronbev account. He knows that a big order is overdue, but Ron and Hugh are both out of town on vacation and aren’t due back for another week. Jeff is also quite aware that today is the last day for sales to be counted in a sales contest that offers salespeople and their customer support teams the opportunity for a big bonus. Jeff’s team of three support staff and two salespeople have worked hard on the Ronbev account all year, and the results have been very positive. He feels they deserve to win the award and the bonus.

Unfortunately, he is well aware of Ron’s standing request to personally initiate orders. He has spoken to Ronbev often about creating a CRM system that would allow him to make assumptions about the order based on past history and feedback. Jeff knows that such a system would save Ronbev time and money. However, as he sits in his office today contemplating the situation, it is not in place.

Questions to Consider

- Should Jeff go ahead and place the order he knows is coming and win the contest, while risking the anger of Ron Yokum?

- How much latitude should a salesperson assume in closing the sale when he or she has an established relationship with a customer?

During the sales process, you and your firm set certain expectations that customers have a right to believe you will meet. These expectations relate to all phases of your product and service. When customer expectations are not met, customers perceive a performance gap between what you promised and what you delivered. Performance gaps result in customer complaints.

Customer complaints are not something to be dodged or avoided. In fact, customers should be encouraged to share their postsale concerns. Otherwise, how will the sales organization ever know that a problem exists that needs to be corrected? The following performance gaps are among the most common sources of postsale complaints:

- • Product delivery. Classically, when problems occur with product delivery, it is due to a service failure outside the direct control of the salesperson. However, you must not give excuses, blame someone else, or act as though delivery is not your problem. Your customer expects you to research and solve delivery problems.

- • Credit and billing. Again, this problem is usually not due to some direct action or lack of action by the salesperson. Regardless, you are the customer’s main contact person. If problems occur on the invoice, you should shepherd your credit department toward solving the problem and keep your customer in the communication loop during the process.

- • Installation of equipment. If a delay occurs on a promised installation, or if something goes wrong with the installation, a customer can quickly become frustrated. Sometimes you must travel in person to the installation site to display empathy and responsiveness to the customer—even if you don’t have the technical expertise to contribute to the installation itself.

- • Customer training. Promising that your firm will train a client’s users of your product is very common. If a breakdown occurs somewhere in this process, you must become involved in straightening out the mess.

- • Product performance. A gap between a customer’s expectations of your product’s performance and its actual performance may evoke the most severe of complaints. While other complaint issues are relatively transient, problems with the product itself get at the core value the customer expected from the purchase. Guarantees and warranties can go a long way toward appeasing customers with product performance problems, but any customer would prefer to have a product that works right in the first place. Hence, the salesperson should work hard to communicate with the customer during a period of malfunction, and also help the customer find alternative solutions during a period of repair.

Communicating with Customers about Complaints. Salespeople are not absolved from communicating with customers just because they’ve closed the sale. In fact, properly handled complaints are strong opportunities for salespeople to show customers that they have the customers’ long-term best interests at heart. Well-handled follow-up to customer problems—service recovery—can be a powerful solidifier of long-term customer relationships.10

Here are a few guidelines for salespeople to follow in communicating with customers about problems after the sale:

- Listen carefully to what the customer has to say. Especially if he or she is upset, let the customer vent. Use active listening skills and good body language (eye contact, nodding in agreement, etc.). If the correspondence is by phone, interject verbally occasionally to let the customer know you are listening and you understand.

- Never argue. Never get emotionally charged about the problem. Simply evaluate the complaint and work with the customer to formulate viable solutions.

- Always show empathy. Understand the customer’s point of view about the problem.

- Don’t make excuses. Don’t say, “Your order was late because our truck broke down.” Focus on fixing the problem. And never, ever, make negative remarks about or blame other people inside your company.

- Be systematic. Work with the customer and your company to develop specific goals for solving the problem, including a timetable, action steps, and who will do what. Don’t set unrealistic expectations for solving the problem. That will only widen the gap between your performance and the customer’s expectations.

- Make notes about everything related to the complaint. Keep the notes updated as things progress.

- Express appreciation. Sincerely thank the customer for communicating the complaint and show by your words and actions that you value his or her business.

Although handling postsale problems and complaints is an important aspect of follow-up, successful salespeople are proactive in their follow-up. The idea is that the seller and buyer will communicate regularly to build each other’s business. Many salespeople develop a communication plan with customers between sales calls that include touching base by phone, email, and mail. A particularly effective approach is to check with the customer right after delivery of an order just to ensure everything is as expected. Usually the customer will simply say everything is fine. But when a problem has occurred, the correspondence ensures the salesperson can deal with it quickly.

The predominant use of email for customer follow-up creates a need to educate salespeople about its effective use (and potential abuse). Global Connection explains important elements of email etiquette, especially in communicating across geographic borders and cultures. Following these rules will ensure that this outstanding communication tool enhances your relationship with customer around the world rather than detracting from it.

Global Connection

Proper Email Etiquette Avoids Cross-Border Faux Pas

Email correspondence continues to grow as a communication medium around the world and has usurped other more personal means of contact in most cases. The average businessperson sends and receives about 90 email messages daily.

Although email is certainly powerful and popular, it’s not always the most effective way to get your ideas across to clients. This is particularly true when communicating across language and culture, as email cannot capture nuances and intent the way voice or face-to-face communication can. Between the limitations of ASCII text, odd line breaks inserted by mail servers, clients who use bizarre terms, spamming, never-get-to-the-point authors, tedious email lists, and hard-to-decipher unsubscribe routines, it’s amazing anything at all gets properly communicated across borders.

To use email effectively in customer follow-up and make sure customers read and understand your messages, follow the six simple guidelines here:

- Always include a detailed subject line. Because email messages don’t go through a screening process or gatekeeper, many people use the subject line to determine which messages get read and which get instantly deleted. Even if your message is important for the recipient, if you make the subject line vague or leave it blank, there’s a good chance the message will never get read. Be sure your subject line reflects the message’s content. Trying to trick recipients with “sensational” subject lines will only make them wary of future correspondences from you. Keep your subject line brief—the more concise and truthful your subject line is, the greater the chance your recipient will read your message (and future messages from you).

- Allow ample time for a response. Nearly everyone regards email as “instant communication” and expects an immediate response to every message. But immediate responses are not always feasible. Depending on your recipient’s workload, log-on habits, level of smartphone usage, and time constraints, responding to your message may take several days. The general rule is to allow at least three days for a response. If you don’t receive a reply, resend the original message and insert “2” into the subject line. So if your original message subject lines reads, “product information you requested,” the resent subject line will read, “product information you requested—2.” If your second attempt doesn’t get a response, consider calling your recipient and alerting him or her to your message.

-

Know when and when not to reply to a sender. One challenge with email is that everyone wants to have the last word. As a result, an email trail can continue for days without the new messages adding anything. Consider this typical email exchange:

- Person 1: “Let’s meet at 3 p.m. in the conference room.”

-

Person 2:

That works for my schedule, too. See you then.

- Person 1: Great. Looking forward to it.

-

Person 2:

Me, too. Talk with you later.

- Person 1:Okay. See you at 3:00.

On and on the exchange continues, simply because neither person can resist the temptation to reply. Such correspondences not only waste time but take up bandwidth space on the server and add to people’s frustration as their email boxes fill. If your intended reply does not add anything to the original message’s objective, don’t send it.

On the other hand, know when you definitely should send a response. If someone emails you a document to review, a simple acknowledgment that you received it and are reviewing it is sufficient. Don’t force people to wait in limbo, unsure of the status of their request. Give a brief confirmation when you receive important messages, similar to the order acknowledgments you receive from online retailers.

- Use your reply button properly. All email programs have a “reply” and a “reply to all” option. Using the wrong one could cause you undue embarrassment. Unless you want everybody on the original message to read your message, it’s wise to simply use the “reply” button.

- Set up your reply features appropriately. When you set up your email program’s reply preferences, you have many options to choose from. To make replies easy for you and your recipient, set your new message to appear as the first block of text, above the original message. Placing your reply message below the original can confuse your recipient, who may not scroll all the way down and may think you did not add any new information. If you are replying to a series of questions, either restate the question before each answer or type “See answer below” at the top of your reply, then go back into the original message and type your answers there. Use this second approach only if you can easily distinguish your answers via different colored or styled text.

- Ask permission to add clients to your message list. Because of the sheer number of emails your customers receive daily, always ask permission before you automatically put someone on any sort of listserves. And while you may enjoy receiving jokes, photos, and silly cartoons throughout the day, others may not appreciate such items taking up space on their server. Finally, be cautious how you convey very large file attachments. Often recipients become frustrated when you send really big files that are over their servers limit, resulting in emails without their planned attachments.

Strict adherence to these approaches will eliminate much of the ambiguity, confusion, and miscommunication by email that is common when doing business across borders.

Questions to Consider

- Have you ever committed a major email faux pas? What was it and what did you do to fix it?

- Why are the email etiquette tips above especially important to observe when communicating across borders?

After the sale, companies have the opportunity to focus on several other important customer-building activities.

- • Customer satisfaction. Sales organizations need an ongoing program to measure and analyze customer satisfaction—to what degree customers like the product, service, and relationship. Although the marketing department usually leads this initiative, the sales force often participates in the process. It certainly benefits from the information by altering sales approaches to better serve customer needs.

-

• Customer retention and customer loyalty. After the sale is a good time to work on building customer loyalty and retention rate. One reason periodic measurement of customer satisfaction is important is because a dissatisfied customer is unlikely to remain loyal to you, your company, and its products over time.

Importantly, however, the corollary is not always true: Customers who describe themselves as satisfied are not necessarily loyal. Indeed, one author estimates that 60 to 80 percent of customer defectors in most businesses said they were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” on the last customer survey before their defection.11 In the interim, perhaps competitors improved their offerings, the customer’s requirements changed, or other environmental factors shifted. The point is that businesses that measure customer satisfaction should be commended—but urged not to stop there. Satisfaction measures need to be supplemented with examinations of customer behavior, such as measures of the annual retention rate, frequency of purchases, and the percentage of a customer’s total purchases captured by the selling firm.

- • Reexamine the value added. Customers should be analyzed regularly to ensure that your value proposition remains sufficient to retain their loyalty. Review the various sources of value discussed in chapter 3 to determine if you are maximizing the added value for your customers. Gaining feedback from customers after the sale has been institutionalized in many sales organizations. IBM, for example, includes such feedback as a formal part of its performance evaluation process for everyone who interacts directly with a client. This is part of a concept called “360-degree feedback,” and it will be discussed further in chapter 13.

-

• Reset customer expectations as needed. This topic was discussed in chapter 3 but is well worth visiting again. Many salespeople try “to underpromise and overdeliver.” This catchphrase encourages salespeople not to raise unrealistic expectations from their customers and reminds them to try to deliver more than they promised in order to pleasantly surprise the buyer. Overpromising can get the initial sale and may work once in a transactional selling environment, but a dissatisfied customer will likely not buy again—and will tell many others to avoid that salesperson.

Managing customer expectations is an important part of developing successful long-term relationships. Customer delight, or exceeding customer expectations to a surprising degree, is a powerful way to gain customer loyalty. The follow-up stage is a great time to overdeliver and delight customers, as well as to close any lingering gaps between customer expectations and the performance of your company and its products.

All CRM systems allow for managing your business with any customer through all aspects of the relationship. As described in chapter 5, CRM systems use underlying data warehouses into which information about customers is entered at all touchpoints, or places where your firm interacts with the customer.

The follow-up activities in selling should all be documented in a CRM system. Among the analyses such documentation makes possible are:

- • Tracking common customer postsale problems, sharing these problems with others in your firm, and creating viable solutions.

- • Sharing postsale strategies among all members of the sales organization.

- • Documenting and comparing levels of satisfaction, retention, and loyalty across customers.

- • Developing product and service modifications, driven by customer input.

- • Tracking performance of individual salespeople and selling teams against customer follow-up goals.

Very early in a salesperson’s career an opportunity should be provided for him or her to learn and practice good listening skills. Then, these skills should be modeled and practiced periodically through role play—hopefully during sales manager work-withs—including sensitizing the salesperson to both verbal and nonverbal buying signals.

The onus is on sales managers to create a healthy environment for closing—an environment that recognizes the desired win-win nature of contemporary selling, not one that allows a high-potential customer relationship to be thrown offtrack by inappropriate, pushy closing techniques. Such a culture is created by training and reinforcement, and by everyone in the company (especially managers) practicing what they preach on a day-to-day basis.

You know from reading this chapter that salespeople should not translate the failure to get an order or close a deal into a personal rejection. The sales manager is in the best position of anyone in the firm to promote a healthy “can-do” attitude among his or her salespeople. When a sale is missed, the manager must work with the salesperson to debrief the sales process so that together they can come up with approaches that are likely to be successful with the next customer—or in future contacts with the customer who failed to close. Establishing a culture and environment that allows salespeople to approach closing the sale and its inherent challenges with the right attitude is largely a function of the professionalism of sales management in the firm and the level of trust shared between sales managers and their salespeople.12

Finally, sales managers need to fully realize the power of follow-up after a sale to strengthen customer relationships, and then actively encourage their salespeople to invest in follow-up activities. Ideally, an assessment of how well salespeople engage in follow-up with customers should be a part of their performance review process and they should be rewarded accordingly. Evaluating salesperson performance is the topic of chapter 13.

In contemporary selling, closing the sale should not be a traumatic experience for either the salesperson or the customer. Because the goal all along has been to work toward value-adding win-win solutions that benefit both parties and lead to a long-term relationship, closing is a natural outcome of the seller–buyer dialogue.

It is important for salespeople to become familiar with many closing methods so they can apply the best methods to different situations. Successful salespeople know that not getting an order is not a personal rejection. They understand the importance of learning from such experiences but not basing their self-worth on them. Attitude is very important to successful closing. Salespeople who believe in themselves and the product and show confidence, honest enthusiasm, and tenacity will close more business than those who don’t. Empathy with customers and their needs is central to successful closing.

Good salespeople recognize a variety of verbal and nonverbal buying signals and respond appropriately with a trial close. It is necessary for salespeople, especially those new to the field, to become familiar with common closing mistakes in order to avoid them when dealing with their customers.

Postsale follow-up with customers provides an excellent opportunity to add considerable value to the client and the relationship. Excellent salespeople provide follow-up not just to handle customer problems and complaints but proactively to ensure customer satisfaction and loyalty.

closing the sale

buying signals

empathy

silence

assumptive close

minor point close

alternative choice close

direct close

summary-of-benefits close

balance sheet close

buy-now close

rejection

attitude

tenacity

trial close

performance gap

customer complaints

service recovery

Role Play

Before you begin

Before getting started, please go to the Appendix of chapter 1 to review the profiles of the characters involved in this role play, as well as the tips on preparing a role play. This particular role play requires that you be familiar with the chapter 7 and 8 role plays.

Setting the Stage

Assume all the information given in the chapters 7 and 8 role plays about Alex’s sales call on Tracy Brown (Alex’s longtime buyer at Max’s Pharmacies). Again assume you are at the meeting between Alex and Rhonda a few days prior to Max’s sales call and that the goal now is to brainstorm several potential closing approaches that Alex might use in the upcoming sales call on Tracy to present Happy Teeth. Again, Rhonda wants to role-play a buyer–seller dialogue with Alex about these potential closing approaches so he will have a chance to practice them before making the actual sales call on Tracy.

Alex’s Role

Work with Rhonda to develop a list of specific closing methods likely to be relevant in the Happy Teeth call on Tracy. Develop a specific dialogue for the role play in which Tracy (role-played by Rhonda) responds differently to the different closing approaches—sometimes accepting, sometimes expressing concerns/objections, and sometimes neutral or nonresponsive. Develop dialogue that allows Alex to respond properly to each reaction expressed by Tracy. Refer to the sample buyer/seller dialogues in the section on closing methods for ideas on developing the list and the role-play dialogue.

Rhonda’s Role

Work with Alex on the above.

Assignment

Present a 7–10 minute role play in which Alex plays himself in a mock sales call on Tracy (Rhonda gets to role-play Tracy). Focus only on the closing part of the sales dialogue. Use as many of the closing methods in the chapter as you find appropriate to the situation. Vary Rhonda’s responses so that Alex can use different approaches to moving the sale forward after each. In some cases Rhonda should come up with concerns/objections after the trial close so that Alex can demonstrate proper negotiation techniques to overcome the concern and then try to close again. At the end of the mock sales call, Rhonda should take no more than 5 minutes to provide constructive feedback/coaching to Alex on how well he used the closing methods.

- What images of “closers” did you have before reading this chapter? List as many negative stereotypes of closing as you can. How has the chapter’s point that “closing should become a natural part of the communication process” between buyers and sellers changed our opinion of closing?

- Why is attitude so important to successful closing? What are some aspects of a positive attitude that you believe contribute to success in closing (and in selling in general)?

- Once a salesperson sees one or more buying signals from a prospect, he or she should trial close. What happens if the prospect doesn’t close at that point? Why is this outcome actually favorable for continuing the dialogue with the buyer and moving toward closing?

- Why is it important to be able to use different closing methods in different situations?

- A sage of selling once said, “Your job as a salesperson is to do 80 percent listening and 20 percent talking.” Do you agree? Why or why not?

- Review the list of common closing mistakes in the chapter. Give specific examples of how each might affect your success in a sales call.

- What is it about postsale follow-up that makes it one of the most important ways to enhance long-term customer relationships? What specific things can you do in follow-up to accomplish this?

- Consider the statement “Customer complaints are customer opportunities—but only if we know about them.” Do you agree or disagree? Why?

- How do CRM and the use of databases in selling enhance closing and follow-up?

Mini-case 9 St. Paul Copy Machines

Paula Phillips arrived back at her office at St. Paul Copy Machines around 4:00 on Tuesday afternoon. As she sat behind her desk looking dejected, her sales manager, Jeff Baker, showed up to ask how that afternoon’s sales call had gone.

Paula had been scheduled to meet at 2:00 p.m. with a few representatives from Direct Mailers Inc. to finalize their purchase of a high-speed, multifunction copy machine. Direct Mailers uses these high-end machines to copy direct-mail pieces it sends out for a wide array of clients. The pieces are typically coupons that companies pay to have sent to local residents in an effort to entice customers to visit their businesses and begin to buy their products or services. Because Direct Mailers’ clients require high-quality reproductions of their coupons, Paula has already made several sales calls on buying center members at Direct Mailers to get to know their operations and their specific requirements for a copy machine.

At today’s meeting, Paula had planned to present to the Direct Mailers’ representatives the copy machine that would fulfill all of their needs, resulting in an order for a new machine. However, once Jeff saw the look on her face, he knew that things had not gone as planned.

| JEFF: |

Hi, Paula. How did it go at Direct Mailers today? |

| PAULA: |

You don’t want to know. I’m not sure we’ll be able to salvage this sale. |

| JEFF: |

Why don’t you tell me what happened and we’ll see if there’s anything that can be done to give us another shot at the sale. |

| PAULA: |

Well, it started when I first walked in there. You know how things have been sort of rough with me lately. I haven’t made a sale all month, so I probably didn’t have the best attitude going in. Nevertheless, I made my presentation and it seemed to be going great. |

| JEFF: |

What kind of questions did they ask? |

| PAULA: |

The standard questions about warranty, when the copier could be delivered and installed, purchase price, annual operating cost, and how much more productive they can be with this new machine versus what they currently own. I handled all of these questions and they still were reluctant to make a decision today. |

| JEFF: |

What closing technique did you use? |

| PAULA: |

The one I always use—the balance sheet method. This method has worked for me in the past and I’ve used it on dozens of buyers. Not all of them buy from me, of course, but hey, you can’t have success all of the time, can you? Plus, I get enough buyers that I make my quota most years. I mean, what else can I do? |

| JEFF: |

How many items did you end up with on both sides of the balance sheet? |

| PAULA: |

On the “reasons for buying” side I had six items and on the “remaining questions” side I had three items. I know that sounds like quite a few remaining questions, but at least the reasons for buying were greater. They were going along with the proposal pretty well at this point in the presentation. In fact, I’m pretty sure that they had decided to purchase the copier. It had gotten to the point where we were standing around chitchatting about various things. |

| JEFF: |

What kinds of things? |

| PAULA: |

You know, things like how much their business could improve with a new copier and how much more efficient they could be from an operational standpoint. You know the feeling and the look of how people relax when they have made a decision. We had reached that point and I thought it was done. I waited about 15 more minutes to pull out the contract for them to sign because they seemed to be having a good time talking about these issues among themselves. |

| JEFF: |

What do you suppose made them change their mind? |

| PAULA: |

In the conversation, someone mentioned all of the money they had just spent on supplies to operate their current machine—copy toner and stuff like that. Before I knew it, they had decided that too much money had been sunk into those supplies and they couldn’t justify a new copier. Having spent money on supplies for the current machine wasn’t even on the balance sheet list of “remaining questions.” It just came out of the blue and then I was stuck. |

| JEFF: |

It’s obvious that you’re tired. Why don’t you use the rest of today to finish your paperwork and make sure you have everything you need to see your clients tomorrow. We’ll talk about this some more when you get into the office tomorrow afternoon. |

As Paula finished her paperwork and checked her schedule for Wednesday, Jeff pondered what their conversation would include the next day.

Questions

- What mistake(s) common closing mistakes did Paula make in her sales call with the representatives from Direct Mailers Inc.?

- Why do you think Paula’s closing method did not work? What could she have done differently to give it a better chance to work? What other closing methods might have worked better in her attempt to get this sale? Write a brief script for what Paula could have said using one of the closing methods you just identified.

- What do you recommend Paula do now? Are there any key follow-up activities she should undertake to get another opportunity to make this sale with Direct Mailers?

For some strange reason, many salespeople who can present a flawless case for their products or services and calmly overcome the toughest of objections suddenly flounder at the point of asking for the order. Yet asking for the order is the logical conclusion of everything that has preceded it, from qualifying the prospect to giving the presentation. Since few prospects volunteer their order, salespeople seldom ring up a sale without asking for it.

This extensive set of questions will help you determine where you stand in using closing skills effectively. The idea is to get you to think about where you might need some coaching and practice in the important area of closing the sale.

- Do you ask for the order several times during the course of your presentation?

- Do you try for a close on the first call?

- Do you regularly ask prospects which alternative (models, payment plans, delivery schedules, etc.) they prefer rather than whether they are interested?

- Is your presentation enthusiastic and positive, suggesting that you fully expect to get the order?

- If necessary, can you usually give compelling, plausible reasons for buying immediately?

- Do you avoid giving the impression of high pressure in your requests for the order?

- If the prospect hesitates, do you tactfully try to determine the reasons for his or her reservations, then answer them fully and persuasively?

- Failing to get an explicit yes, do you proceed to try to get your prospect to do something (get figures, call in an assistant for backup information, show you where the display would be placed) that may be interpreted as approval of your proposition?

- Do you unobtrusively introduce your order form early in your presentation?

- Are you usually prepared to meet the standard objections to your product or service?

- Have you the tools for an order at hand, ready to use (catalog, spec sheets, order form, etc.)?

- Do you ever arrive armed with the order form already filled out (based on an intelligent estimate of the prospect’s needs) and requiring only a signature?

- If you’ve dealt with the customer before, are you familiar with his or her buying patterns, idiosyncrasies, pet peeves, and complaints?

- Do you usually have a fairly accurate idea of the prospect’s creditworthiness and ability to pay?

- Before calling on the person with authority to buy, do you ever visit other departments or buying center members to determine the firm’s needs and otherwise gather “selling ammunition”?

- Can you describe three good ways any prospect is losing out by not buying your product immediately?

- Are there any tax advantages to your proposition that might make it more appealing to your prospects?

- How do you handle the buyer who seems impressed by your offer but hesitates, explaining, “I’ll have to discuss it with my partner (boss, committee, spouse, etc.)”?

- Are you ever guilty of behaving in a manner that tells your prospect, “I don’t really expect an order now”?

- Conversely, are you ever so obviously elated by the possibility of getting the order that the customer backs away?

- Are your presentations benefit-oriented so the prospect is continually aware of what he or she will gain by buying?

- Do you always maintain control of your sales calls—or does the prospect frequently control the agenda?

- Have you ever been so afraid of being turned down that you did not ask for the order?

- Do you keep some reserve ammunition for the end of your presentation—some benefit or advantage tucked away in your back pocket that you can use in a final attempt to get the prospect to buy?

- Do you always know in advance your product is right for the prospect?

- When you fail to close, do you get out of the prospect’s place of business quickly but not abruptly?

- When you do close, do you get out of the prospect’s place of business quickly but not abruptly?

- Suppose you feel your price is the one thing standing in the way of a sale. How can you make it more palatable to the prospect (delayed billing, financing help, trade-ins, leasing plans, etc.)?

- How can you convince a prospect who says “I want to think it over” that any delay in the purchase of your product is unwise?

- Do you demonstrate your product to prospects?

- Do you usually manage to get the prospect to participate in the demonstration in some way, by handling something, examining, reading, operating, or testing it?

- Do you tend to assume a prospect will never buy from you if he or she says no on your first call?

- How often do you call on a prospect before giving up?

- Do you keep up to date on personnel changes in the firms you already deal with on the assumption that the next buyer is, for all practical purposes, a brand-new prospect?

- Do you keep in touch with prospects who have turned you down to find out if circumstances have changed in your favor?

- In a typical presentation, how many times do you ask for the order?

- A prospect turns you down, claiming satisfaction with the present supplier. How, in terms of personal service, can you break through this loyalty barrier?

- Describe three ways you can ask for the order without literally asking for it (e.g., “Shall we bill you this month or next?”).

- How is your product unique? That is, how is it genuinely different from all the competition?

- Can you name the person with the authority to buy in three of your largest prospects’ offices?

- When was the last time you simply gave up on a sale, convinced that pursuing it any further was a waste of time? Think. Has anything (business conditions, your product line, your price, the prospect’s needs, etc.) changed since then that may provide a reason for trying again?

- You ask for the order from an out-of-town prospect who tells you he or she prefers to buy locally. Your answer?

- The prospect puts you off with “I have a reciprocal arrangement with your competition.” What’s your answer to that one?

- When you run into an objection that you cannot answer, do you make it your business to find a convincing answer that you can use the next time you encounter it?

- You sense the prospect isn’t saying yes because of doubts about his or her own judgment. How do you go about changing his or her mind?

- The prospect tells you that she needs a little more time to decide and suggests that you call back in a few days. When you do make that phone call, how do you ask for the order this time?

- When was the last time you reassessed your customer’s needs (by talking to him or her or an associate, taking stock of what he or she has on hand, projecting future growth, etc.)?

- In your presentations, are you fully aware of your prospect’s biggest problem and prepared to show how buying from you will solve it or alleviate it?

- How will your product help your prospect become more competitive?

- With three specific prospects in mind, what are the best times of the year in each case to ask for the order? Why?

- Similarly, what are the least promising times of year to ask for the order in each case. Why?

- If you can somehow help a prospect use or sell more of your product profitably, it follows that he or she will buy more. How can you help your two toughest prospects get more profit out of your product?

- What information (sales, product, research, news items, etc.) is currently of help in closing sales?

- Are you using that information with all of your prospects to the best possible advantage?

- If your product is part of a full line, do you regularly try for tie-in sales?

- Do you check back on former customers who, for one reason or another, have stopped buying from you?

- What percentage of your sales calls do you turn into actual sales?

- On which call are most of your initial sales made (first, second, third, fourth)?

- Which of your prospects do you think are ripe for a close this week?

- When, specifically, are you going to ask them for their orders?

Closing is a natural and expected part of a client relationship. As a challenging and rewarding part of a salesperson’s professional activities, it deserves your best efforts.13