Edward’s flight to Stirling castle and then to Dunbar and on to Berwick ended the campaign of 1314. The financial cost had been enormous and there was nothing to show for it. Raising another army immediately would have been an impossible strain on the economy and the loss of so many members of the English political community was a further barrier. The lords and gentry who were now dead on the battlefield or prisoners in Scotland would not be available to raise troops, fulfil command and administration roles or serve as men-at-arms. The communities of northern England had provided the bulk of the infantry and could not be expected to fill the ranks of a new army, so men would have had to be recruited from the southern counties, which would weaken defences against raids or even invasion from France.

A number of major lords had refused to serve in 1314 and several of those who had were now prisoners. Many had been killed and even if their heirs were of military age, many of them would have had their hands filled with the business of establishing their leadership within their communities, and very few of them would have had any significant command experience. Additionally, the mere fact of the defeat – and its scale – was hardly an encouraging factor. Few men would have retained any confidence in Edward as a commander, and the situation did not reflect well on those of his senior subordinates who had escaped death or capture. For some, there would have been a big question mark over the value of pursuing the war at all, given the costs, the risks and the potential benefits of victory. There were probably some men of a more pious nature who saw the hand of God at work and concluded that the war was not justified. Beyond that, there was the question of whether the war could be won. Robert had managed to survive every initiative taken against him, but even if he could be killed and the Scots defeated in battle, was it not likely that the Scots would find another captain to champion their cause? Edward Bruce would almost certainly take on the challenge and, whether he did or not, Edward Balliol might well do the same.

None of these factors would be enough necessarily to dissuade Edward II from raising another army, but there was the very real possibility that it, too, might be defeated. Additionally, even if a victory could be achieved, what was the benefit? A relatively modest number of men might make good the grants of lands, offices and titles bestowed on them by Edward I, but it was abundantly clear that Scotland could not be garrisoned by a few handfuls of men in scattered castles and peels. If an occupation government was to be successful, it would have to be secured by very large forces and at enormous costs. Most, if not all, of the castles that had been slighted by Robert and his lieutenants would have to be repaired and the garrisons would have to be paid and supplied from English resources. It was not even clear that the manpower to provide the garrisons could be recruited. From 1297 to 1314, it had been possible to enlist men-at-arms and archers from Scottish communities and to extract the knight service of several counties to provide soldiers to man the castles and peels. This was likely to be much harder to achieve in the wake of such a major defeat. There were certainly some men available: Scottish men who had not entered the peace of King Robert and had become exiles, but there were not enough of them to provide the sort of active garrisons that would be needed to impose Edward’s rule. Furthermore, Robert had established a general practice of accepting such men into his peace on reasonably attractive terms, but also made it clear that there was a limited window of opportunity and that men who did not enter his peace – at the price of abandoning any landholding from or allegiance to the kings of England – would be forfeited forever. Given the choice of submitting to Robert, accepting his kingship and being reinstated to some or even all of one’s heritage, or spending who knew how long as a pensioner of the English Crown in the hopes that one day Plantagenet or even Balliol kingship would be restored, it would hardly be surprising if a high proportion of these ‘disinherited’ lords sought to make their peace with the Bruce party.

All in all, the events of 1314 left English military prestige and confidence severely shaken. This was a major issue given Edward’s relationship with France and the challenges to English authority in Ireland and Wales. The failure of the campaign also generated profound dismay in the communities of northern England. If Edward could not protect his subjects in Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmorland, there was always the risk that the political communities in those areas would look to someone who could provide them with better lordship: King Robert. Although Robert always maintained that he had no ambitions to conquer English territory, there were clear symptoms of a collapse in northern confidence in Edward’s kingship. In the years after Bannockburn several landholders in northern English counties, having paid the ransoms that Robert demanded for refraining from destruction, approached Robert for legal decisions or to have their charters confirmed.

There was also increasing cause for concern to other communities further south. Part of the price for peace in the northern English counties was Robert’s insistence on free passage for his troops from ransomed communities, which potentially gave his raids much greater range. From Robert’s point of view, the repeated incursions into England were not simply a matter of keeping his army in good condition – though clearly that was a significant factor – or even with easing his own financial problems. He entertained hopes that such activity would eventually force Edward to open negotiations for a proper peace agreement, but he misread the situation. Quite simply, Edward was just not that concerned about the communities of northern England.

Edward was neither willing nor able to abandon Scottish ambitions; to do so would be an admission of defeat and would be seen as throwing away the accomplishments of his father. This was hardly realistic as his father had, in fact, failed to defeat the Scots, but he had achieved at least an appearance of nearing his objective in 1304–05. At the time of Edward’s death in 1307, Robert Bruce was an insignificant threat and, superficially at least, Scottish independence as a political concept was very close to being extinguished – at least in English public perception.

Edward II inherited the Scottish war from his father; the war was Edward I’s project and over the years it became something of a fixation, and – for Edward II – to some extent it became a means of deflecting attention from internal problems. To a degree, it had served a similar function for Edward I. In the late 1290s, England was sometimes on the brink of civil war and focusing attention on the Scottish situation helped to give a common purpose to the differing factions in domestic politics.

By 1314, the desire to conquer Scotland had become so thoroughly entrenched that it was virtually impossible to abandon it. Massive sums of money had been committed and there would be nothing to show for so much effort if Edward simply accepted Robert’s kingship. Bannockburn did not bring the war to an end: Edward would mount further expeditions into Scotland, but he was never able to bring the Scots to battle on their own soil. However, his forces suffered defeats on English soil and this did nothing to improve Edward’s standing among his nobles or the wider community.

The economic damage incurred from Robert’s operations in northern England did not have a major direct effect on Edward’s personal income, but the raids did lead to depopulation as people moved south to avoid the conflict; this, in turn, made it more difficult to recruit adequate numbers for English operations in Scotland, so the cost in manpower and money had to be found from counties in the south, and that did not help to make Edward popular with his subjects. Additionally, the prospects for his Scottish pensioners became increasingly bleak. Their number was not great, but it was not trivial either, and they became a steady drain on Edward’s treasury. The same applied to men who had been granted Scottish estates and offices. Clearly, they now had no realistic chance of gaining their lands or salaries any time soon, but many of them had to be compensated for their losses with grants of land in England or money from Edward’s treasury.

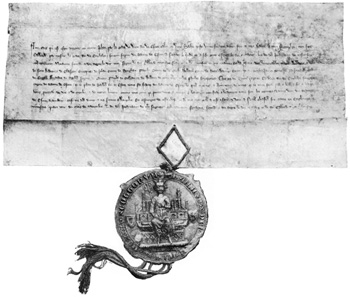

42. Letter patent of John Balliol, acknowledging the feudal superiority of Edward I.

In addition to the internal dissent that was encouraged by Bannockburn, Edward’s prestige abroad – which was never very strong in the first place – was seriously undermined. Bannockburn gave Robert political and military credibility, particularly in France and the Low Countries, who could now more safely resume trade on the sort of level that had pertained in the years before the war.

Nevertheless, one area of success was in the diplomatic struggle. Edward was able to dissuade the pope from lifting the sentence of excommunication from Robert, which had been decreed for his murder of Sir John Comyn of Badenoch in 1306. However, it is questionable whether any of Edward’s subjects really saw that as a victory of any consequence.

For Robert, the victory brought any number of rewards. His control of Scotland was complete and effectively unquestioned; the men who might have opposed him were either dead or exiles in England. However, strictly speaking, he was still not universally regarded as the legitimate king. Although John Balliol had abdicated in 1296 and then some years later had forsworn any and all rights in Scotland, he had done so under duress and therefore there was some doubt about the validity of his actions, and even more doubt about whether he could legitimately give away the rights of his heir, Edward Balliol. As long as Balliol fils lived, there would always be a risk that a pro-Balliol movement might arise and attempt to topple Robert in order to put the legitimate heir on the throne. This might have seemed a little far-fetched in the immediate afterglow of such a stunning victory or in the wake of Robert’s successful campaigns in England, but the principle of legitimacy in inheritance was of enormous importance in medieval societies. A mere six years after Bannockburn there was a plot to murder King Robert. Barbour points to Sir John de Soulis as the man that the conspirators were seeking to put on the throne, but he also reports that a band of 360 men-at-arms had gathered at Berwick to carry out a coup once Robert had been dispatched. These men were undoubtedly drawn from the ranks of those who had lost their lands through their opposition to the Bruce party, and their intention was to make Edward Balliol king in Robert’s place. The plot was a complete failure and many of the conspirators were tried and executed, the remainder fleeing to England or France, but clearly there was still life in the Balliol cause.

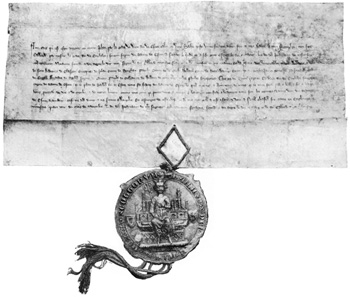

43. The seal of John Balliol.

Robert faced other problems. An attempt to take the war to Ireland initially looked like it might bear fruit and even result in Edward Bruce becoming king of an independent Ireland, but in due course the attempt fizzled out and Edward Bruce himself was killed in action at Faughart on 4 October 1318.

Despite these setbacks, Robert was able to conduct the affairs of the kingdom with considerable success and there was a general economic recovery despite some very poor years for agriculture. In one sense, the military picture was relatively bright. Control over the more pastoral areas of Scotland allowed Robert to recruit larger numbers of men-at-arms, which helped to make his raids into England more effective. Douglas and Moray were able to gain victories against the forces of Edward II, but the range of their operations was limited. They could make forays as far south as Huntingdonshire, but could not really threaten Edward’s political power base in the south of England. Robert’s armies could win the battles, but securing a permanent peace continued to elude him.

In the meantime, as he pursued his military and diplomatic campaigns, Robert was able to devote himself to the business of running the country. Like any medieval king, his domestic priorities revolved around ensuring that his rule was firmly established throughout the realm and encouraging economic development. Possession of all of Scotland’s ports allowed a resumption of the wool trade. Wool was the most significant export of both England and Scotland. Of all the tradeable wool sold in late medieval Western Europe, something approaching 80 per cent of it was produced in England and virtually all of the rest came from Scotland. Wool was not the only export, but it was the only one subject to export taxes, and, as such, there is more evidence about the wool trade than any other commodity; however, that does not mean that other trade goods were insignificant. Furs, hides, timber, salt, honey and grain were all of some consequence, but none came remotely close to wool in terms of generating income either for merchants of for the Crown. Export is generally accompanied by import, and medieval Scotland was no exception. Iron was in short supply locally and a great deal had to be brought in from abroad, but a large proportion of the imported material consisted of luxury goods. Of these, wine was probably the most significant as there was no domestic production whatsoever. The same applied to spices, which appear frequently – and in remarkably large quantities – in medieval records. The most popular spices seem to have been cumin, pepper and galingale (a form of ginger), which rather suggests that the Scottish devotion to curry (chicken tikka masala was possibly invented to appeal to Scottish tastes) is not a modern phenomenon.

In the immediate aftermath of Bannockburn, and intermittently for some years thereafter, war itself was a major source of economic activity. The ransoms that Robert demanded from English towns and counties helped to ease his financial difficulties, though it would seem probable that a great deal of that income was spent on wages for his soldiers. The forces that Moray, Douglas and Robert himself led into England maintained very high standards of discipline and that could only have been maintained if the troops were rewarded with cash rather than by being allowed to take plunder. Even so, there were opportunities. The men captured at Bannockburn, at Myton and Byland, and at scores of other actions could only obtain their liberty by paying ransoms to their captors, so a good many Scottish soldiers became personally wealthy through their service in the field.

Imposing law and order was a major task for Robert and his lieutenants. The war had produced extensive social dislocation. There were a good many landless men who had turned to robbery and extortion to make a living. This was not a uniquely Scottish problem. Even in peacetime, the business of hunting down bandits was part of the fabric of life in every country in Europe, but it was something that flourished in periods of conflict due to the fact that the class of men who would normally have responsibility for ensuring peace and good order were generally more focused on the business of conducting a war. In peacetime, the knight service owed to the Crown and to figures of local authority could be committed to the task of suppressing bands of criminals, but in war the service was needed elsewhere.

Eventually it would be a series of internal political crises in England that would give Robert the treaty of ‘final peace’ that he desired. Edward was never able to exert the level of control over his nobility that his father had mostly been able to achieve, but a mixture of social conservatism and divisions in his opposition kept him on the throne long after he had demonstrated that the task of being a competent king was beyond his abilities. A chain of revolts and refusals to give service undermined his authority and in May 1325 he made a huge tactical error in sending his eldest son, the future Edward III, to act as his proxy in giving homage to the King of France for the Duchy of Gascony. Edward’s French queen, Isabella, had already travelled to France to negotiate a peace treaty, but now, with custody of her son, she refused to return at Edward’s request. In September the following year she mounted an invasion and within a short time Edward was not only defeated, but imprisoned.

An individual changing sides from one party to the other was considered to have ‘entered the peace’ of the king and was thereby pardoned his previous resistance – though normally for a price.

In January 1327, Edward was formally charged with an enormous range of failures, including the ‘loss’ of Scotland, though in fact neither he nor his father had ever really secured their rule there in the first place. He agreed to abdicate in favour of his son and was placed in prison for life, but as long as he lived there was always the chance that his supporters might set him free and restore his kingship. Edward may not have been a very successful king, but the principle of legitimacy that constituted such a threat to Robert Bruce from the Balliol family was just as strong in medieval England as it was in Scotland. Additionally, although Edward III was now king in theory, he was still too young to rule in person and the government of the land lay with Isabella and her lover, Roger Mortimer.

The crisis in England had a bearing on the situation vis-à-vis Scotland. After years of demanding ransoms from communities in the north of England, the nearest thing to peace that Robert had been able to force from Edward II had been a truce to last for thirteen years – the medieval equivalent of a political problem being ‘kicked into the long grass’. King Robert now took the view that the truce had been a personal arrangement between himself and Edward, and that his death rendered that arrangement null and void. Accordingly, Moray and Douglas renewed their operations. Robert may have hoped that Isabella and Mortimer, preoccupied with their own difficulties, might be brought to the peace table. Arguable, but they simply proved to have the same attitude to Scotland as Edward and were prepared to ignore the plight of the northern counties. However, since part of the rationale offered for forcing Edward II to abdicate had been the fact that he had failed to conquer Scotland, they could hardly afford simply to surrender to Robert’s demands for recognition of his kingship and a full and lasting peace. Additionally, abandoning the conquest of Scotland might further alienate the young Edward III, since he – and, by this time, quite a sizeable proportion of the political community and the people as a whole – had come to see Scotland as part of the birthright of English kings. Accordingly, they raised an army and sent it north with the young Edward at its head.

The campaign was a disaster. The Scottish and English armies traipse up and down Weardale in the rain. There was very little actual fighting and the Scots had the better of what there was. At one particularly dispiriting juncture, Edward III was very fortunate to avoid capture. The Weardale campaign was a humiliation for Edward and for the English army in general; it also emptied the treasury and dissipated what little political capital Isabella and Mortimer still had.

The moment had come to make peace. King Robert’s health was failing and he was anxious to reach agreement; his terms were generous, including a payment of £30,000 – an absolutely gigantic sum for those days – for the construction of an abbey dedicated to praying for the souls of those who had died on both sides. He may or may not have been aware that the money would go straight into Isabella and Mortimer’s pockets, but he had made the right sort of gesture by providing the money for the stated purpose.