Edward started the process of raising an army as early as October 1313 and was probably already planning an expedition before that. Doubtless he would have mounted a major response to Robert earlier had it not been for his internal political difficulties, his problems in France – not least the thorny business of negotiating the performance of the homage that he owed for Gascony – and the great burden of debt that he had inherited from his father. Similarly, Robert had started gathering his troops several weeks before the campaign and was able to have his forces in place before the English army mustered at Berwick and Wark.

The size of the Bannockburn armies has been the subject of much debate. Chronicle figures simply cannot be taken at face value. Barbour’s claim that there were 30,000 Scots and 100,000 English has been the basis for many estimates, though largely this would seem to be a matter of later writers assuming that he had inflated the armies by a factor of four, resulting in 7,500 Scots and 25,000 English. These figures are not altogether impossible, but in fact Barbour was not really offering figures to be taken literally. Many medieval authors used multiples of three to give an idea of scale in much the same way that we might use the term ‘thousands’ or even ‘millions’ when we just mean ‘a lot’. In medieval literature 300 can mean ‘a modest body’, 3,000 can be taken to indicate ‘a substantial body’ and 30,000 to mean ‘a very large body’. Barbour’s use of ‘30,000’ for the Scots and ‘100,000’ for the English is probably best interpreted as meaning that the Scottish army was very large and the English army was very much larger still. For Barbour, and his audience, the key information was that King Robert had assembled a massive force from across the country, demonstrating his political power. That said, Barbour did not shy away from the fact that there were still Scots in the English camp, telling us that Edward had the services of a great company of Scottish men-at-arms from Lothian. Although this is undoubtedly true, the claim does require a little examination. It is probably reasonable to assume that the company in question was drawn from more than just Lothian.

29. Grave effigy of Sir Roger de Trumpington. This image dates from about 1280; by the time of Bannockburn the absence of any plate armour other than knee protection would have made the bearer look rather outdated, but would still have been acceptable as equipment for a man-at-arms.

Although Roxburgh had fallen to the Bruce party in February 1314 and Edinburgh only a month later, It is more than likely that Robert had not, as yet, been able to fully assert his power in Roxburghshire and Lothian; even if he had, there would almost inevitably be men who felt that Edward would be able to crush Robert in the event of a major battle and that even if there was no actual engagement, he would be able to recover and repair the castles and re-impose his government, at least in southern Scotland. For men in that position, turning out for the Bruce party would have been an enormous risk no matter if they were supportive of Robert’s kingship. If Edward was able to restore his authority, they would face the strong possibility of forfeiture or, if captured, the death penalty for treason.

Not all Scots were happy about Robert’s acquisition of the throne in the first place; he was, after all, a usurper. Furthermore, there was no strong tradition of political leadership by the Bruce family in the south-east of Scotland. So long as King John’s heir was alive, Robert could not be the legitimate king. Additionally, some of those who might have been willing to accept his kingship would have been discouraged by the fact that he had killed a political rival in a church and had been excommunicated.

Although there was clearly still opposition to Robert’s reign and, naturally, doubts that he could withstand Edward’s invasion, the numbers in Barbour’s ‘great company’ were hardly enough to make a major contribution to Edward’s army. Even under the best of circumstances, it is unlikely that Lothian, Berwickshire and Roxburghshire combined could raise more than a few hundred men-at-arms, and there is nothing to indicate that Edward II – or his father for that matter – ever made any effort to raise infantry service from these counties. The summer of 1314 was not, in any case, the best of circumstances. Although Robert could not be confident of exerting his authority to the utmost degree in the south-east, he certainly had more sway there than Edward II, so it is unlikely that the contribution of Lothian men-at-arms amounted to more than a few score, especially given that a party who did attempt to join the English army arrived in the vicinity only to discover that Edward had already been defeated and therefore promptly changed sides.

These Lothian men were not, however, the only Scots in Edward’s allegiance. A considerable number of Scots who had not come into King Robert’s peace were living as pensioners of the English Crown. Some had lost their lands because they had refused to renounce their allegiance to the Comyn family or to King John or to King Edward; others had been refused admission to the Bruce party because of acts in the past. For these men, the only hope of recovering their lands and titles was through service to the Plantagenet cause. They were relatively few in number, but their presence did have a political significance, since it was an indication that there was some Scottish support for Edward’s rule, but, like the company of Lothian men, their contribution to the man-at-arms element of Edward’s army was marginal.

Although we do not have accurate information about the size of Edward’s army, we can make some viable deductions based on what we know of previous and later expeditions for which the pay rolls and other record material survive. This was a particularly large force by the standards of late English medieval armies, but it was nothing like the 100,000 men suggested by Barbour. The major armies recruited for service in Scotland under Edward I and Edward II included a heavy cavalry element of about 2,500 men-at-arms, as shown by horse valuations and pay rolls. This is a little misleading since various categories of men did not have their service recorded. A few chose not to serve for pay and a rather large number served without pay to gain pardons for crimes, but neither category amounted to a very significant portion of the cavalry element. There would have been similar elements in the army of 1314, but there were also a number of major lords – the Earl of Lancaster, for example – who refused to serve at all. On balance, the figure of 2,500 men-at-arms is probably a valid assessment. In other armies of a similar scale in this period, the men-at-arms were divided into four units, three led by important nobles and one, rather larger than the others, nominally directly under the king’s command. Assuming that the 1314 army adhered to this structure then three bodies of about 500 men and one of 1,000 would fit the evidence rather well.

The situation is less clear in regard to the infantry. Edward issued writs to raise over 21,000 men, but it is clear from other armies of the period that actual recruitment seldom exceeded two-thirds of what was called for. Additionally, desertion was a constant problem, though the 1314 army was probably not in existence for long enough for that to have become a critical factor. Conscription was not the sole source of men: there would have been additional troops who served to procure pardons and some who volunteered in search of plunder or adventure or to avoid troubles at home, but these are unlikely to have constituted a very significant number. In total, it is unlikely that Edward had much more than 15,000 infantry under his command by the time the army made camp at Stirling on 23 June, and probably something closer to 12,000 would be a more realistic estimate. However, naturally, there would have been a substantial number of non-combatants as well.

Of these 12–15,000 infantry, the greater number would certainly have been spearmen, the balance being archers, but we should not assume that the latter were the equivalent of the well-drilled bowmen of the English armies of Edward II’s reign. It seems very likely that a random proportion were simply issued with bows at the time of enlistment or at the muster, regardless of ability. This is probably less significant than it might at first seem. Obviously, it would result in there being only a very small number of skilled marksmen, but the chief function of the archers would be to shoot at large, closely packed formations of spearmen or cavalry – hardly the most demanding of targets.

Like the cavalry, the infantry were not simply an amorphous horde of troops. There was a system of articulation. We cannot be absolutely certain that the army of 1314 utilised the same system as those of the preceding and subsequent decades, but it would be anomalous if it did not – so much so that we should expect that some comment would have survived. The evidence from other English armies indicates three clear levels of administrative articulation: large units commanded by officers called ‘millenars’, which consisted of smaller units commanded by ‘centenars’, which in turn were made up of smaller units under the command of ‘vintenars’. It would be simplistic to assume that these units were necessarily exactly 1,000 or 100 or 20 strong respectively, but there is a clear implication that they would have been of that order. We know from record material that there were men who were referred to as ‘corporals’ and ‘petty officers’, but it is not clear whether these were any more than alternative terms for the lowest rank of infantry leaders, the vintenars. There is a possibility that when an army was newly mustered, these three levels of articulation did actually reflect numerical strength quite accurately, though clearly desertion, sickness and, of course, combat would all have an effect – especially desertion, which was clearly a perennial problem for English armies operating in Scotland to a far larger degree than in those deployed to France or Ireland, simply because it was a much more practical proposition for an individual or a group of men to return home on foot or horse. For operational purposes, it seems likely that the commands of the millenars were combined into large units.

Barbour’s assertion that the English army was in ten divisions is probably better seen as literary rather than literal, though it is possible that he had access to material that he did not necessarily fully understand, and that the English army really was organised in ten divisions of infantry in the form of the commands of the millenars. To what extent these units were tactical entities as well as administrative ones is impossible to say, yet there is at least one example of a millenar being held responsible for the failure of the men of his formation to provide an adequate night guard on campaign.

Edward’s infantry was not a mere afterthought. He and his subordinates were familiar with fighting in Scotland and Edward was eager to ensure that a large infantry force was raised, since he believed that there might well be extensive fighting in difficult countryside, where the cavalry could not operate effectively.

The Scottish army was certainly rather smaller than that of Edward II, which is no more than we should expect given the disparity in population. We can, however, be reasonably confident that Robert did not raise an army based simply on numbers. The tactics he adopted depended on having well-equipped infantry and we are told by Barbour that in the weeks before the battle Robert turned away volunteers who did not have adequate armour and weapons.

It is much harder to identify any form of articulation in the Scottish army, though clearly there must have been one to enable administration of a force of several thousand men, if only for the purposes of regulating working parties and issuing rations. Since it is clear that Robert concentrated his troops at Stirling some weeks before the battle it is reasonable to assume that there was some form of articulation at various levels to facilitate personal and unit training. It is possible to discern an element of this in the leadership structure. The Earl of Moray had command of a major portion of the army – a body of 2,000 men or more – but in his action near St Ninian’s chapel on the first day of the battle, he took only a portion of that force into the fight. Barbour describes Moray’s force in that engagement as being 500 men ‘of his own leding’ (leading). This implies that they were men who owed him their military service directly in his capacity as Earl of Moray. This highlights a difference in the political structures of England and Scotland. After the conquest of 1066, William the Conqueror granted the title of ‘earl’ of this or that county to his more prominent followers, but the title was not directly attached to the land; it was, essentially, honorific.

In Scotland – as in France or pre-conquest England – an earl was a regional potentate with a wide variety of powers, including the administration of certain aspects of justice and responsibility for raising troops on behalf of the king. Scotland did not consist of earldoms alone, and, as in England, the sheriff or the burgh council had an obligation to raise a certain number of men when required. The earl’s official responsibility might – in fact, perhaps generally did – extend beyond his own lands within the earldom, but even if certain landholders were exempted from his authority, they could hardly afford to ignore the most powerful man in the area. It was a system that could be open to abuse. When King Robert was Earl of Carrick, he was obliged to promise not to use his position as an earl to demand military service for his own purposes from men who were not his tenants but happened to reside within the bounds of his authority, but only to call them out in the national interest.

30. Looking south from the approximate position of King Robert’s division on the afternoon of 23 June.

The king and the greater lords, such as the Earls of Carrick or Moray, had two quite separate forms of military responsibility. Mustering the rank and file of the army was a matter of administering the ‘common army’ service which was, in theory, due from every able-bodied man, but in practice was generally only demanded from men of a certain level of wealth – those who could afford to purchase the necessary equipment. The other was knight service: a military obligation on those who held estates – usually heritably – in exchange for service as men-at-arms, regardless of whether they were knights. A large estate might be held in exchange for the service of five or ten knights or more and a small one might be held for a fraction of the service of a knight. How exactly fractional service was discharged is not clear from the record evidence, and some of it may have been delivered in the form of archer service or a monetary payment, or as a shared expense between a number of neighbours who each owed a fraction of a knight to the king’s army. The latter was probably more prevalent than one might expect, since a good deal of fractional knight service came about through the division of a property between female heirs, and the two or more properties that came into being by that route would, as a rule, be adjacent to one another.

31. The contemporary material indicates that the Scots moved down to the plain from higher ground in the New Park. They probably formed up in the area where the new Bannockburn High School stands.

32. Once the Scots had formed up they had to negotiate this steep slope before deploying on the plain.

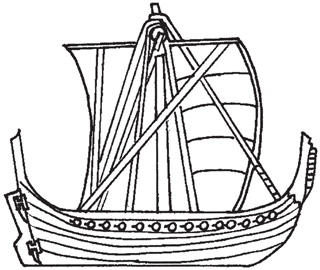

33. A Scottish ‘birlinn’ or galley. Vessels like this were used extensively by Robert I in his campaigns on the west coast of Scotland. A number of barons and other landholders were obliged to provide manned warships like this for their ‘knight service’ rather than serving as mounted men-at-arms, though it was not uncommon for such men to serve in both capacities as required.

In England the title of ‘earl’ was a heritable honour, but it did not carry any specific legal or administrative responsibility. The Earl of Gloucester or the Earl of Cornwall did not have any particular rights, privileges or duties within those counties, but any earl was likely to hold a great deal of property spread across the whole country and be an important figure in the national political community accordingly. This was not the case in other European kingdoms. In France or Scotland an earl would wield a great deal of almost sub-regal power – holding courts, administering local defence, raising troops for national armies – but only within his stated jurisdiction. The earl did not, however, own all the land in his county. Major properties within the earldom might be held by any number of people and might in some instances be excused various obligations to the local earl.

The body of men-at-arms raised from knight service was small compared with that available to the King of England, but was not insubstantial. Although Robert did not as yet have absolute control in some of the areas that would traditionally have produced the greatest numbers of men-at-arms, it is most likely that nearly two decades of war – and several years of steady military success – would have produced a number of men who would not normally have aspired to knight service, but for whom war presented an opportunity for social advancement. On balance, it would not be remarkable if Robert had something in the region of 1,000 men-at-arms under his command in June 1314.

Another possible aspect of articulation is archery. There are a number of references from both later and earlier sources that refer to an individual being the leader of Scottish archers. It is possible, therefore, that there was a capacity for, or perhaps even general practice of, organising the archers as one or more separate commands within the army structure. Given the relatively small numbers involved – perhaps 10 per cent of the entire strength – this would make sense both administratively and tactically, but the evidence is far too meagre to come to any firm conclusions. On balance, given the sum of what we know of the strength and nature of Scottish and English armies of the later medieval period, we might make an informed guess that the armies of 1314 are unlikely to have exceeded 7−8,000 Scots and 16−18,000 English at most.

The English army is unlikely to have been any smaller than 10,000 foot and 2,000 men-at-arms, but is equally unlikely to have been any greater than 16,000 foot and 3,000 men-at-arms. The Scottish army almost certainly falls with the range of 5,000 foot and 1,000 men-at-arms (though many, and perhaps all, certainly served on foot in the main engagement), with an upper limit of perhaps 8,000 infantry.

These are, however, estimates of combat strength; they take no account of the large numbers of ancillary staff that undoubtedly accompanied both armies and we cannot be totally certain that records of all the contributions to the army have survived. Edward certainly called for troops from Ireland, but there is no clear evidence to indicate that they were ever actually raised, let alone that they made the journey to Scotland or, if they did, that they joined the main army before the battle. However, it would seem much more probable than not that if they had crossed over to Scotland there would be some record of their passage, their activity or their return (or failure to return) to Ireland.