Stirling was hardly terra incognita to Edward in 1314. He had very probably been there himself during the time he had spent in Scotland, and if he had not visited there himself, at least some of his senior officers – particularly those who had held offices in the occupation government – had done so in the past. The English army left its mustering areas at Wark and Berwick on 17 or 18 June and marched on Edinburgh through Lauderdale and Tweeddale. Since Edinburgh castle had fallen to the Scots three months previously, there was little reason to go to Edinburgh other than possibly to meet up with a convoy of supply shipping and to intimate to the local populace that the occupation government was being resurrected. The army marched westward to Falkirk, where it spent the night of 22/23 June before moving on toward Stirling. They had made reasonably good time, but it was clearly far from being a forced march – presumably a deliberate policy to ensure that the army was not unduly tired when it arrived in what Edward and his lieutenants hoped would be the battle area. However, they believed – not unreasonably – that Robert might well try to avoid a general engagement.

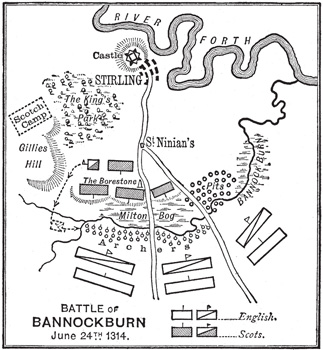

34. The Battle of Bannockburn as envisaged by Oman and Gardiner, though it bears very little resemblance to the contemporary source material.

At some point during the march, two formations were detached from the main body of the army, a force under the Earls of Gloucester and Hereford taking what we might consider the main road from Falkirk straight to Stirling and a second force consisting entirely of men-at-arms under Sir Robert de Clifford and Sir Henry de Beaumont – including Sir Thomas Grey, father of the author of Scalacronica – moving closer to the course of the River Forth on the low ground to the east of the New Park.

These operations were undertaken for a variety of purposes. One role of the cavalry force under Clifford and Beaumont was clearly to bring about a technical relief of the garrison in Stirling castle. In a sense, this was almost superfluous given that the English army had arrived within striking distance and in great force within the stipulated period, but protocol and form were important aspects of medieval war and politics. Bringing a force into the castle would certainly satisfy the requirements of the surrender compact, but it would also conform to the spirit of the age. It would be a feat of arms – an act of chivalry – and would play well in chronicle accounts, which Edward could be confident would be written after the campaign; in fact, he had brought along the noted English poet Friar Baston for that very purpose.

35. The open farmland on which he main battle took place. Contrary to Victorian interpretations, all of the contemporary material makes it clear than the main engagement took place on firm ground, not among bogs and marshes.

There were more practical considerations. Edward was determined to bring the Scots to battle and was concerned – understandably, given the extensive experience of his own and his father’s Scottish campaigns – that King Robert would not stand and fight, but would withdraw into the west or north and avoid a major engagement until such time as a shortage of food and money forced Edward to abandon the campaign.

Placing a strong mobile force to the eastern flank and rear of the enemy might not prevent the Scots from retreating, but it would certainly make the process more difficult, since a largely infantry army on the march would be vulnerable to sudden cavalry attacks. Alternatively, if the Scots did not withdraw, Edward and his subordinates would hope to gather intelligence about their strength and dispositions. The other force, under Gloucester and Hereford, had a similar role. The Scots could hardly ignore their presence and must either try to block their path to Stirling or take to their heels and therefore allow the English a clear passage to the town. That would not have been the preferred option for Edward as he was anxious to inflict a serious defeat on the Scots, but it would not be completely unattractive. Robert had brought a large force to Stirling and kept them there for weeks of training. If he did not put his army to any use, his prestige as a military leader would be undermined, and his political credibility as the man best suited for protecting Scotland from invasion would be severely compromised. Robert had raised large forces in the past and avoided battle, but he could not do so indefinitely without impairing his reputation and authority.

With any luck, from Edward’s perspective, the two forces would achieve one or more of a number of positive outcomes. The castle would be relieved and there might be one or more actions in which his forces would be successful, possibly forcing Robert to abandon the area entirely. It was even possible that one successful fight, even on a relatively small scale, might demoralise the Scots so much that their army might disintegrate; this had, after all, been the case at Dunbar in 1296. Although these were all acceptable possibilities, the real hope was that the two forces would not only reveal everything about the strength and position of the Scots, but that they would effectively pin the enemy and force Robert to give battle whether he wanted to or not.

Edward could afford to be quite confident about the enterprise. The smaller cavalry force moving between the Scottish positions to their left and the River Forth on their right was powerful enough to take on fairly substantial opposition and mobile enough to avoid a major body of the enemy if that became necessary. The large force under Hereford and Gloucester might well score a significant victory by itself, but if the enemy proved to be too strong for them, it would provide a barrier to the Scots so that the rest of Edward’s army could complete their march to a suitable campsite.

36. The Bannock burn. The burn was probably rather wider in 1314, but even today it has a very soft and muddy floor which would be a considerable barrier to armoured men trying to escape the battlefield.

The only suitable site for such a large force lay between the Pelstream and the Bannock burns. Although Edward and, to a lesser degree, his subordinates have been the subject of a great deal of criticism for their choice of a camp, they really had very limited options. Like any medieval army, Edward’s force included a very large number of horses and a considerable quantity of oxen as draught animals and as beef on the hoof, in addition to perhaps 15,000 men or more. All of these would require fresh water in large amounts and the two streams – each rather larger then than they are today due to drainage developments that have changed the water course considerably – would be absolutely vital if the army and the animals were not to suffer dehydration at the end of a day’s march in hot, sunny weather. The strip between the burns was more than large enough to accommodate the army and its baggage, but the burns themselves would give a degree of protection against any Scottish surprise attacks during the short summer nights. This was considered – by Edward at least – to be a real possibility. The campsite would not provide any sort of barrier between the English army and the Scots, who were camped on the higher ground to the west, but neither Edward nor his lieutenants seems to have been at all concerned that the Scots might mount a direct full-scale attack from the high ground. Given their lengthy experience of fighting in Scotland, this was not an unreasonable conclusion; to date, the challenge had been more a matter of getting the Scots to commit to battle at all, let alone to make a set-piece attack on firm, open ground that would favour greater numerical strength in general and especially the far larger contingent of heavy cavalry available to Edward.

A carse is a low-lying area which is prone to flooding, or at least saturation, during the winter months, but forms dry pasture in the spring and summer.

The Scots, of course, were waiting for the arrival of Edward’s army. The three main formations of the army, commanded by the king, the Earl of Carrick and the Earl of Moray, were all stationed on the high ground of the New Park, with the baggage and stores to the rear, possibly around the area of the southern end of the King’s Park. The King’s Division was closest to the enemy, with Carrick’s men to the rear and Moray’s troops further to the north, where they could intervene if an English force marched across the farmland to the east of the king’s position. Carrick, roughly midway between the two, could march quickly to the aid of either the king or Moray if necessary, but could remain out of sight until required.

Gloucester and Hereford’s force marched well in advance of the main body of the army and crossed the stretch of the Bannock burn, which lies to the south of the present National Trust for Scotland Visitor Centre, and proceeded up the slope toward the nearest Scottish position.

Gloucester and Hereford may have thought that they were facing the entire Scottish army, which they must have known would have been a rather larger force than their own, but more realistically they were probably aware that they would be encountering only a portion of King Robert’s force. Assuming that they were aware of de Bohun’s unsuccessful attack on King Robert, they would very likely have deduced that the enemy to their front would consist of Robert’s own immediate command and that there was therefore probably not a great discrepancy in numbers, but even if they did not, they would have been well aware that over the preceding decade and more since Falkirk, the Scots had not often chosen to make a stand in front of a determined advance. In that light, it was not an unreasonable decision to make an attempt to dislodge the Scots from their position and even possibly cause them to panic and desert the battlefield in disorder.

37. A view toward ‘The Entry’, where the Earls of Gloucester and Hereford made the first attack and where de Bohun was killed in a single combat with King Robert.

The Scottish position was, however, naturally strong and may have been enhanced to favour a defensive stand. At the top of the rise, the road passed into an area known as ‘The Entry’, where the gap between two stretches of woodland became narrower to the left and right of the road. The governor of Stirling castle had sent a report to Edward informing him that the Scots had been mustering at the New Park, training and busily blocking the paths in the woodland – presumably to prevent bodies of troops from outflanking their position. According to some sources, the Scots had also dug narrow pits or ‘pots’ at a particular location and had camouflaged these with sticks and grass so that unwary horsemen might ride into them and be thrown when their horses stepped into them and broke their legs. It seems most likely that this was the location of the ‘pots’, though no sign of them has ever emerged from aerial photography or archaeological surveys.

The purpose of such a stratagem was not so much to inflict casualties as to deny sections of the terrain to the enemy. As soon as the first rider fell from his horse, his comrades would be aware of the danger and act accordingly. Assuming that the pots were distributed on either side of the road, they would have the effect of denying a flank approach against the Scots and of funnelling the English advance toward Scottish spears and at the same time giving protection to the Scottish archers among the trees on either side. Regardless of the existence or otherwise of the pots, the English force moved into The Entry, presumably hoping to force their way along the road to Stirling, but found their route blocked by a large body of spearmen and Scottish archers who shot at them from woods on either flank.

There was an action, but it does not seem to have lasted for very long; Gloucester and Hereford could make no headway and there was little point in standing around taking casualties if they could not make progress toward Stirling castle, so they broke off the action and made their way back down the slope and then eastwards to the camp area. There is no reason to assume that Gloucester and Hereford’s force had been weakened in any material way either in confidence or numbers, but the action had been beneficial to the Scots. It did not prove that cavalry without adequate infantry support were at a disadvantage when confronted by steady infantry – that had been demonstrated many times in the past – but it was certainly a boost to Scottish morale, which was already high after King Robert’s rather public dispatch of Sir Henry de Bohun in a single combat.

There was a wider consideration, however. Edward’s army had suffered a reverse, and Robert could now, if he chose, withdraw and avoid a major battle without damaging his political standing in the community. Part of the price of gathering a large army was that if he never brought the troops into action he would eventually start to look indecisive, even weak, which – particularly as a usurper – he could not afford if he was to retain the credibility and prestige necessary for effective kingship.

No sooner was this engagement over, than Robert received news of another development. While Gloucester and Hereford had been approaching along the main road, the second force of men-at-arms under the command of Clifford and Beaumont had been moving along another road through the fields to the east of the New Park and were headed toward the area around St Ninian’s chapel, presumably en route to relieve the Stirling castle garrison and thus fulfil the bargain struck between the commander, Sir Philip Moubray, and the Earl of Carrick some three months earlier. Formally discharging the pact was of limited significance; in fact, it had possibly already been dealt with since, according to Barbour, the agreement was that an English army had to come within 3 leagues of the castle for a relief to be recognised. The term ‘league’ is a challenging one and often appears in chronicles without absolute clarity as to whether it means 1 mile or 3, but assuming that in this context the term meant 3 miles, the castle had already been relieved by the afternoon of 23 June, and Moubray was therefore no longer bound to surrender his post. More realistically, the security or otherwise of the garrison would depend on the developments of the next twenty-four hours or so. If the Scots withdrew, the castle would be safe for as long as a major English army could be maintained in Scotland. If Edward retired to England without striking a major blow against the Bruce administration and imposing his own government securely in its place, the Scots would simply return and lay a new siege. Equally, if Edward was able to bring Robert to battle and defeat him, the Bruce cause would probably be fatally compromised, even if Robert was able to escape with his life. In all likelihood, no one on the English side – and very few among the Scots – had really given much thought to the possibility that Robert might actually force a battle, let alone that he might win it decisively.

38. A well-equipped infantry man of the fourteenth century, with a chapel-de-fer helmet and two thin, padded garments, one under his mail and another over it.

Even so, honour rather demanded that an effort be made to relieve the castle and there was the additional potential value of gaining better information about the strength, dispositions and intentions of the Scottish army.

It seemed to King Robert that the Earl of Moray had lost concentration and that Beaumont and Clifford would be able to reach Stirling unmolested unless immediate action was taken. He told Moray that a ‘Rose was fallen from his Chaplet’ (Barbour) – that he had blotted his copybook – and sent him off to deal with the situation. Moray was the commander of a major formation within the army, probably about one-quarter of the total strength and about one-third of the main strength of the Scots, the rank-and-file spearmen, but he chose to take only a portion of that strength into the fight. Instead he relied on what Barbour terms the men ‘of his own leding’ (leading), which is to say the men who formed his own ‘comitiva’ of about 500 men. These would have been drawn chiefly from his tenants, but would also include men who had chosen to serve under his command over a period of years; they were his personal following who he could rely on to act together as a close-knit team of competent, confident and experienced soldiers.

Moray swiftly led his men down on to what Sir Thomas Grey (in Scalacronica) calls the ‘good ground’ – meaning firm land suitable for cavalry – and barred the way to the town. For Clifford and Beaumont, this was an unmissable opportunity and they actually drew their men back to allow the Scots to occupy a position on the flat plain before making an attempt to charge through them. As it turned out, this was not a wise move. The English cavalry failed repeatedly to break into the Scottish formation and, after a spell of hard fighting, found that they were actually being pushed backwards toward the River Forth. There had been examples in the past of determined and well-drilled infantry successfully repelling a cavalry attack, but this may have been the first medieval example of infantry successfully turning the attack against men-at-arms. After a prolonged fight, the English force eventually split into two parts, one heading for Stirling castle and the other retiring toward the main body of the army. Casualties had not been very high – according to Barbour the Scots did not lose a single man, which seems less than credible – but a number of prisoners were left behind, including Sir Thomas Grey.

Although the clashes of the first day had both been favourable to Robert, he was still not absolutely committed to giving battle. While he was deliberating his course of action, a third engagement took place at Cambuskenneth Abbey. Robert had selected the abbey as a repository for what Barbour describes as his own supplies. No doubt the abbey did house foodstuffs and the like, but it probably also housed Robert’s records. The various lords and officers of the Crown who were obliged to furnish men and the different institutions charged with collecting and delivering the enormous quantities of food and other materials to keep the army in good shape would want to have receipts to show that they had fulfilled the demands made upon them. Because the troops were simply fulfilling the obligations required by national defence, Robert did not – so far as we can tell – have to pay them wages, but the costs would still have been considerable, and his officers, especially the chamberlain and the clerks of the Livery and the Spence (the financial departments of the Scottish Crown administrative structure), would have been busy men.

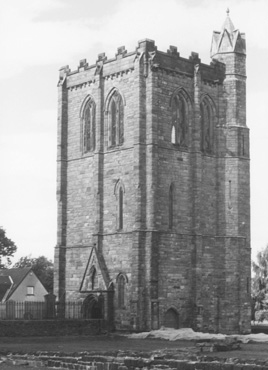

39. The sole remaining building of Cambuskenneth Abbey. During the night of 23/24 June, the Earl of Athol mounted an attack on King Robert’s stores. Of the four actions of the battle, this is the only one of which the precise location can be identified without question.

During the night of 23/24 June, the abbey was attacked by a party of troops under David Strathbogie, the Earl of Atholl. Atholl had been in King Robert’s peace until very shortly before this, and had left Robert’s side in anger because the king’s brother, the Earl of Carrick, had jilted Atholl’s sister. The attack was successful. A number of people were killed, including the elderly Sir William de Airth and various members of the royal household. The king’s stores were destroyed and, in all probability, all the records of the army were lost along with them.

Barbour’s account relates that on the night of 23 June, Robert had still not made a final decision about whether to offer battle the following day. So far the outcome had favoured his troops and there was something to be said for avoiding another engagement. The action at Cambuskenneth Abbey had been a blow, but a minor one, and an event that would not have any political, tactical or propaganda value. The other two actions had been definite successes. Neither had inflicted serious casualties on either side, but Robert could certainly claim to have had a good day. If he now chose to withdraw through the night it was unlikely that Edward would be able to make any effort to pursue the Scots until well into the next day, and it would be difficult, if not impossible, for the English army to close the distance that would separate them from the Scots. It would certainly be possible to detach a major portion of the cavalry, leaving the infantry behind, and catch up with the Scots within a day or perhaps two, but that would be risky policy: the event of 23 June had clearly demonstrated that the Scots were perfectly capable of dealing with unsupported cavalry attacks, and – assuming Robert withdrew into more challenging terrain – there would be some risk of suffering a major defeat. On the other hand, if Robert did retreat, Edward would be able to relieve Stirling castle and would have an opportunity to install a new administration to take the place of the one that had been dislodged over the preceding years. These factors were not so significant as they might at first appear.

If Robert avoided battle, Edward would quickly run out of the money and supplies to keep his forces in the field and would inevitably have to disband at least a large proportion of the army. He might be able to keep Robert at bay with a smaller force, but again that would be a risky policy since Robert had demonstrated his tactical abilities in the past and might go on the offensive. The last thing Edward could afford was to be obliged to abandon his Scottish plans through force. Equally, although Stirling was a major prize, its value was limited unless Edward’s administration could dominate the surrounding area to allow Stirling to be a centre of government. In the past, the occupation government had been able to maintain its authority through possession of an extensive chain of castles and peels throughout the country. This was no longer a viable option. Ever since his first successful campaigns, Robert had made a practice of slighting every stronghold he captured specifically to prevent them being used for this purpose. Most, if not all, of the castles and peels could be repaired, but only at considerable expense and Edward had neither the time nor the money for such an initiative.

The worst-case scenario for Robert – if he chose not to fight – was that Stirling would remain in English hands, but realistically, that would only be the case as long as Edward could keep a major army in Scotland. As soon as he withdrew his forces, the Scots could simply sweep back and Stirling would be in much the same position as it had been since spring 1314. Edward could certainly not afford to raise another army to return later in the year, and it was very doubtful that he would be able to do so the following year, plus he might well struggle to get the necessary political support. The greatest magnate in England had refused to give service in 1314 and was too powerful to be disciplined, and several others had had doubts about the 1314 campaign; indeed, there was some doubt about the wisdom of trying to conquer Scotland at all. As such, it might well have proven impossible to raise an army of any real stature for a campaign in 1315.

There was clearly a good case for Robert to avoid battle, but there were several factors that encouraged a more active stance. Although the two actions of 23 June had caused little material damage to Edward’s army, the results inevitably had some deleterious effect on English morale and a very positive effect on the Scots. The effectiveness of the training of the last few weeks had been clearly demonstrated and the men were ready for a fight. Tactically, Robert’s position was excellent. His forces were still out of sight of the enemy – his strength, organisation and dispositions were secure from view – whereas Edward’s army was laid out on the plain below and could not make a move without being observed. Edward’s army had not made a particularly rapid march from Northumberland, but were certainly not as fresh as they might be, while Robert’s troops were well rested and had every confidence in their leaders. Only a fraction of the Scottish army had been engaged, and for many of the others this would be their first battle, but there would have been a high proportion of experienced men and they had become accustomed to winning. Robert was not in the way of offering battle and only did so when utterly confident of success. His men would have been aware of this and, therefore, Robert could be confident that they would trust him not to lead them into a fight if there was not an extremely high probability of victory. With a well-armed, well-trained, confident army, hungry for victory and in a highly advantageous tactical position, Robert had good reason to believe that this was an excellent opportunity to offer battle.

There were two other factors for Robert to bear in mind. During the late morning or early afternoon of 23 June, he had sent a party forward under Douglas to observe the English army; Douglas had reported back that the English army was enormous, but Robert now ensured that his own troops were told that the English were approaching in a state of disorder. Whether this was true was unimportant; what mattered was that his troops had been given another modest boost to their confidence and morale. The second factor was the appearance of a defector in the Scottish camp. Sir Alexander Seton had been an early supporter of the Bruce cause but the bulk of his property lay in Lothian and Robert’s early failures meant that the occupation government there had been quite secure. Seton either had to accept the forfeiture of his family heritage or accept Plantagenet rule. Unsurprisingly, he had chosen the latter, but that does not mean that he had been happy to do so. Now he approached Robert, telling him of discontent and disorganisation in the English camp and that he was confident that if Robert mounted an attack he would win a great victory; he backed up his claim by offering to fight at Robert’s side so that if there was any question of treachery Robert would be able to ensure that Seton would pay the traditional price.

Seton’s defection was probably not a spur-of-the-moment decision. The Scots had taken the last major stronghold in Lothian a few months before, and although Robert had not yet been able to bring the area fully under his rule, clearly the writing was on the wall. Whether Seton really identified a lack of cohesion in the English army and whether it was the most significant factor in his change of heart is open to question, though presumably he would not have chosen to change sides in what was, essentially, a lull in the battle if he had been confident that Edward could lead his troops to a victory. All the same, his defection was significant. Seton was not quite a member of the magnate class, but he was certainly a major figure in the local political community: a man whose name would be well known throughout the Scottish army, and doubtless Robert made sure that his transfer of allegiance was well advertised to the troops. For all these reasons – and doubtless others of which we are not aware – Robert decided to take the plunge and prepared his army for battle.

An early supporter of King Robert at the time of his attempt to take the throne, Seton soon entered the peace of Edward I and thereby retained his property and his local influence as a member of the Lothian political community. He re-joined the Bruce party on the night of 23/24 June, informing Robert that the English camp was in poor order and that there was an opportunity to strike a major blow in the morning.

Traditionally, the action of 24 June has been described in terms of an English assault toward high ground which the Scots, arrayed in four great circles of spearmen, met with sturdy resolve until the English army was exhausted and broke into a headlong retreat. This is not in any degree borne out by the source material. Robert did not merely offer or accept battle, he actively forced it.

In the early dawn of 24 June – and dawn would have broken by 4 a.m. – Robert mustered his army for battle, probably in the area now covered by Stirling High School. Far from waiting for the English to attack, he moved his columns quickly down to the flat ground and deployed them in three formations with a thin screen of archers to the front. Two of the major forces – under Carrick and Moray – formed up as broad formations some distance apart, with the third, under the king himself, between them and some distance to the rear. This did not pass unnoticed in the English camp. It seems likely that the English army was already preparing for the day, but that they were preparing for an advance toward the Scots, not to receive an attack. This is an issue of some significance. All in all, medieval armies moved in column and fought in line, and redeploying from one to the other was not something that could be easily or quickly achieved at the best of times, let alone in a relatively small area with the enemy in close proximity.

Once the Scots had made their way down on to the plain, they did a remarkable thing: they knelt down in prayer. Edward observed this and asked – perhaps in jest – if the Scots were kneeling to beg for mercy, only to be told that if they were, it was for mercy from God, not him. This is an incident that has generally been seen as a demonstration of medieval piety, and doubtless that had significance to the men on the battlefield, but there may have been a tactical value. The broad and relatively shallow spear formations would only be effective if the ‘dressing’ (the regularity of the ranks and files) of the troops was kept in good order. If the majority of the troops were kneeling down, it would be a great help to what we would now call the ‘junior leaders’ of the units to move up and down the ranks quickly, ensuring that every man was firmly in line with his neighbours, and that the unit as a whole was in the best possible order.

The Scottish army was now deployed on a front of a thousand yards or more between the courses of the Pelstream and the Bannock burns and, at most, a mile from the main body of the English. As they marched eastward toward the enemy, the screen of archers to their front soon came into action against a similar screen of English archers, who had presumably been positioned to obstruct the sort of night attack that Edward and his subordinates had anticipated. The Scots archers seem to have made little impression on their opponents and were either quickly driven off or had instructions to make a demonstration rather than to press the fight. Either way, they had fulfilled their purpose by preventing the English archers from disrupting the advancing spearmen, because by the time the Scottish archers made their exit, the schiltroms were too close for comfort, as far as the English archers were concerned, and they made a quick exit to avoid being overwhelmed.

While this opening phase of the engagement was taking place, at least one senior English commander was taking action. The Earl of Gloucester managed to organise a body of cavalry and mount a charge against the nearest Scottish schiltrom under the Earl of Carrick. Gloucester may have hoped that the Scots would crumble at the first blow or that his attack would at least cause the Scots to pause and perhaps give the rest of the English army an opportunity to complete redeployment for battle, but this was not to be the case. His attack ground to a halt against Carrick’s spearmen and his men were driven back toward the main body of the army. As the distance between the two forces shrank in the face of the Scottish advance, it proved impossible for Gloucester’s men to retire and regroup for a second charge, but Gloucester himself was unable to influence the situation since he had been killed at the outset.

The repulse of this first attempt to stop the Scots in their tracks doubtless put something of a dent in the morale of the rest of the English army, and the scattered and disorganised remnant of Gloucester’s command probably made it more difficult for other English commanders to get their troops into good order to receive the Scottish attack.

40. A well-intentioned re-enactor in the tradition of Brigadoon meets Braveheart; however, neither kilts nor two-handed swords have any relevance to the fourteenth century.

On the other side of the battlefield, Moray pressed forward to contact and some hard fighting ensued, but again it proved impossible to stop the Scottish advance. Clearly things were not going well for Edward’s army, since they were now being forced backwards in increasingly poor order toward their campsite, with an inevitable effect on morale and cohesion. This was compounded by the advance of the third Scottish formation, which the king led forward between the commands of Carrick and Moray so that a complete front was formed, stretching from the Pelstream to the Bannock burns. As the army advanced, effectively as a single body, there was less and less room to organise a counterstroke and, even if an adequate force could be gathered, the opportunity to deliver a blow to the inner flanks of Moray or Carrick’s divisions had been lost.

Nevertheless, the battle was, as yet, far from lost. The Scots were having a hard fight of it and were still heavily outnumbered. There is some doubt about the next development in the battle since it is recorded in only one account. According to Barbour, Edward – or one of his subordinates – was able to get a grip on the situation and bring a large body of archers into action on one flank. However effective it might be against cavalry or close-combat infantry, a schiltrom was a very easy target for archery, and casualties started to mount quickly. Robert had foreseen the possibility that he might need a force to intervene at a critical juncture and had organised a reserve of cavalry under Sir Robert Keith, who now charged into the flank of the archers and scattered them. This force is generally described as being ‘light’ cavalry, but that assumption rests on one word in one line from Barbour’s poem, in which he tells his audience that the horses were ‘lecht’. Whether this means that they were not the strong and fast destriers and chargers generally favoured by men-at-arms is open to question. Barbour may simply have meant that the horses were fresh and mettlesome, or he may only have included the term to complete the metre (rhythm) of the line. In practice, it would make very little difference to the men of the receiving end of the charge. Any body of armoured cavalry that broke into a formation or archers was almost certain to rout their opponents with ease.

The case against this part of the action happening at all, let alone as Barbour describes it, is worth examining. English chroniclers state that the entire Scottish army – including the king, who carried his spear among the rank and file – served on foot. On the other hand, it is most unlikely that Robert did not arrange for horses to be readily available so that any opportunity to pursue the enemy could be exploited or so that he and others might have a chance of making their escape if the battle went badly. One English writer, Geoffrey Baker, writing about thirty years after the battle, informs us that the English archers were unable to make an effective contribution to the fighting as they were in the rearmost divisions of the army and could not shoot for fear of hitting their own comrades. This does make some tactical sense. If, as the Lanercost chronicle states, both armies were ‘arrayed’ at dawn on 24 June, it would be perfectly viable for the close-combat troops to be at the front of the army, given that Edward and his commander expected to have to locate and then advance on the Scots. Had that been the case, the logical approach to deployment would have been to ensure that the archers were not vulnerable to an advance by the Scots, but would be available for deployment once the Scots had been pinned in a particular position, as had been the case at Falkirk.

A ‘riding’ horse, as opposed to a charger for battle. A palfrey was not a breed but a type, and might be little more than a nag or, on the other hand, a very expensive, cherished piece of horseflesh. King Robert was riding his palfrey when he killed Sir Henry de Bohun in single combat. It has been suggested – even stated – that the animal was named ‘Ferrand’; however, the term crops up frequently in horse valuations and simply means ‘grey’.

A type rather than a specific breed of animal, destriers were not terribly common and most men-at-arms were content to have a courser, which was cheaper and easier to replace. Contrary to common belief, they were not particularly large animals, generally between 14 and 15 hands tall and very powerfully built.

For Barbour, the rout of the English archers was a crucial event in the battle, since they now fled toward the main body of the army and caused even greater disorganisation, which, as the Scottish schiltroms pushed on, induced a degree of panic. All of this was compounded by a lack of room to manoeuvre. The two streams that had given Edward’s army the vital supply of fresh water for both men and beasts, and had afforded his campsite and initial deployment area some security from night attacks, now proved to be a liability rather than an asset. Neither stream was necessarily an insuperable barrier to an individual who could carefully pick his way across the least challenging parts of the burns, but both were rather more significant streams than they are today and undoubtedly presented a major obstacle to a body of troops. It is important to bear in mind that there was only a very short period of time from the arrival of the Scots on the plain to the point when both armies were heavily engaged right across their respective fronts. Although the great majority of the Scottish army was now in action, a large portion of the English troops were not yet in the fight. However, extricating a worthwhile force from the main body of the army and then getting them across the Bannock or the Pelstream, with a view to delivering an attack on the flanks or rear of the enemy, would have taken some time and was not, in any case, a very practical proposition. It is not clear that any of Edward’s officers tried to effect such a manoeuvre, but even if they had, there was every likelihood that Robert would have been afforded ample time to take action against any threat to his flanks, or that by the time such a force had been gathered and deployed, the battle would already have been lost.

There is no way of knowing whether leaders in Edward’s army tried to effect a flanking move against the Scots, but if they did, it certainly did not lead to anything. As the Scots pressed forward greater numbers of English troops lost heart and started to make to the rear passing through the camp area, only to find their way blocked by the Bannock burn. Thomas Grey (Scalacronica) informs us that many tried to escape by the route that had brought them to the battlefield, only to fall foul of what he calls the ‘stinking ditch’ and to drown, get crushed underfoot or be picked off by the Scots as they floundered in the muddy stream bed. Others retreated directly away from the Scottish advance and soon found themselves on the western bank of the River Forth. The Forth is still subject to the tide as far Stirling; at low tide the expanse of water is not great, but the exposed banks are deep, sticky mud and would be a challenge to anyone, let alone a man encumbered by even the lightest armour.

At a late point in the battle, another incident may have occurred to undermine the English army. According to Barbour, the grooms, servants and various camp followers of the Scottish army had been stationed well way from the battlefield with instructions to remain there until the fighting was finished. Seeing that the English were defeated, these men – and doubtless women too – gathered behind a leader of their own number and rushed down to the plain to make a contribution to the fighting. There is some doubt about their involvement, but the ‘small folk’, as Barbour calls them, would certainly have existed – medieval armies required a considerable number of skilled and semi-skilled ancillary workers – and it is hard to imagine that they would not have seized an opportunity to take part in the plundering of the English camp and baggage trains. What is less likely is that their participation had any effect on the outcome of the battle. Even if they were only a mile or two from the action – and it is unlikely to have been less – if they started out toward the fight at the point when the English army started to disintegrate, they can hardly have arrived before the final outcome had been decided.

As it became all too apparent that the Scots had won the day, Edward threw himself into the fight but was dragged away from combat by the men who were responsible for the safety of his person, including Sir Giles d’Argentan. The problem now was where to take him. As Edward’s standard was seen leaving the field, those English troops who were still in action finally gave up the struggle and either attempted to surrender or to follow after those who were already attempting to escape. Getting away from the battlefield was, however, easier said than done. To the north there was the Pelstream burn, but there was also, assuming that Barbour’s account is valid, the force of Scottish men-at-arms who had scattered the English archers. A strong body of men might make a safe passage there if they could retain enough cohesion to deter the Scottish horse, but it would be a risky option for a small group or an individual, and any move northward would lead away from the English border and security. To the east there was the River Forth – not a huge river, but any kind of water course is a major obstacle to a man in armour. Furthermore, the banks of the Forth at that point are very broad and soft, so crossing the river is actually much more difficult than it might seem. To the south there was the Bannock burn. Like the Pelstream, it is not a large river, but like the Forth the banks are soft and muddy. According to Thomas Grey’s Scalacronica, this was the main line of retreat and large numbers of English troops ‘fell back on the ditch of Bannock burn tumbling one over the other’.

King Edward’s party forced their way across the Pelstream burn and headed for Stirling castle as the nearest place of safety. Any hope that this might prove an adequate sanctuary was short-lived. The garrison commander, Sir Philip Moubray (the man who had made the surrender pact with the Earl of Carrick three months earlier), informed Edward that although he was prepared to take Edward into the castle and offer him what protection he could, the plain fact was that he was obliged to surrender the castle to the Scots at the earliest opportunity. Even if he refused to honour the agreement, for all practical purposes defending the castle was a lost cause. The Scots would simply restore the siege that they had lifted back in April and the garrison would be starved out or stormed long before there was any prospect of a new army being raised in England to rescue the king; in fact, with Edward holed up in Stirling, there was little prospect of a relief force being raised at all.

Clearly Edward either had to attempt to make his way home to England or face surrendering to King Robert, which would be an unmitigated disaster. The prestige of Edward – and of English kingship in general – would be very badly damaged, which would likely have consequences for his credibility among his subjects in France, as well as finally destroying any standing he might retain among Scots who had accepted Plantagenet rule. Additionally, there would be the political and financial cost of obtaining his liberty. Undoubtedly, any terms would have to include a complete and unreserved acceptance of Robert’s kingship and solemn oaths never to attack Scotland again, but there would also be the matter of a ransom, which might well run into hundreds of thousands of pounds. Edward could be sure of his personal safety – Robert was hardly going to execute him – but equally he could hardly expect to be set free before a ransom had been agreed and at least a substantial proportion delivered.

The chances of making a successful escape were actually quite good. Edward was not alone, but was surrounded by a large party – probably some hundreds – of men-at-arms. Many of these would have been the men of personal retinue, joined by those who had followed the royal banner on their own initiative when Edward left the battlefield. Between them they formed a fairly formidable force. The decision was made to pass round the western side of the New Park and King’s Park and then to proceed to nearest point of safety.

Down on the plain, where the battle was finally coming to a close, Edward’s party was observed leaving Stirling and King Robert dispatched a force of men-at-arms under Douglas in the hope of capturing Edward. Douglas took to the pursuit with his usual determination, but his party was too small to force an action against Edward’s following. During the pursuit Douglas encountered Sir Laurence Abernethy, who had brought a party of men-at-arms – eighty strong, according to Barbour – to join the English army. Ever the realist, Abernethy quickly decided that the Plantagenet cause was lost and joined Douglas in the chase. However, even with these unexpected reinforcements, Douglas could not risk an engagement and settled for picking up those English stragglers who fell behind the rest of the party. Barbour describes a hell-for-leather ride through the counties of the south-east as far as Dunbar, where the earl, still firmly opposed to the Bruce party, admitted Edward and provided him with a boat to take him to Berwick, where he would be in no immediate danger. In fact, the pursuit was probably a more leisurely business than Barbour describes, since the horses of both sides would soon have collapsed with exhaustion if they had been driven to trot, let alone gallop over such a long distance.

While Edward made his way to Dunbar, at least one of his commanders was trying to rescue what he could from the fight. Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke, gathered a force of infantry and men-at-arms that was strong enough to discourage any serious interference and marched south. Others were less fortunate. A party escaped as far as Bothwell, where the commander of the garrison claimed that he could only accommodate the leaders of the group, who then entered the castle only to be taken prisoner. For the rest of the army, the situation was more than bleak: it was desperate. No doubt many managed to escape the battlefield only to be killed or captured as they fled south. Of those who did not die on the field, many were drowned or crushed trying to escape across the Bannock or the Forth; many more surrendered – some apparently even to peasant women – in the hope that their value as prisoners for ransom would help to keep them alive.

Throughout most of the war, a man who was captured could secure his release by payment of a ransom. Ransoms were normally set at a level that the prisoner could reasonably be expected to raise and payment terms might be spread over some years. Ransoms were usually a matter between the captor and his captive, though it was not unusual for the Crown to receive a portion of the money since the captor would – as a general rule – be serving in the king’s army.

Robert certainly took a major gamble at Bannockburn, and two of the greatest Scottish medieval historians, Professors Ranald Nicholson and Geoffrey Barrow (and others in his wake), have concluded that it was a gamble he should not have taken. His authority as king largely depended on his military success. Some men had joined his cause through family traditions, patriotic convictions or coercion, but for many Robert seemed to offer the best prospect for delivering what medieval writers called ‘good lordship’: secure and steady government that could be relied upon to provide stability and prosperity. A single defeat on the battlefield would utterly compromise his credibility even if he escaped, and if he was captured he would certainly face execution.

All battles involve risk, but Robert had taken pains to load the dice very firmly in his own favour. Edward II had made reference to taking an army to ‘our castle of Stirling’ as early as October 1313, but that was not the sole target and he might easily have chosen a different course for his expedition, or at least one that encompassed other objectives. The clear challenge to Stirling that was created by the pact between the Earl of Carrick and Sir Philip Moubray did not completely force Edward’s hand, but it would have been a sign of weakness had he not made a serious effort to relieve the garrison before midsummer. If anything, the pact gave Edward a clear target, since Robert would have to make some sort of demonstration of opposition. With any luck, Robert would muster a significant force and be brought to battle.

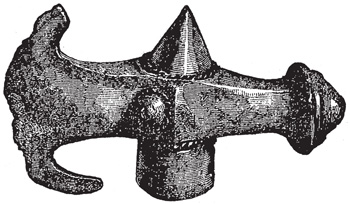

41. The head of a battle-hammer allegedly recovered from Bannockburn battlefield.

For Robert, the Stirling area had very real advantages as a place to obstruct, if not engage, an English invasion. The strategic value lay in the fact that Stirling is right in the centre of the country and had, by medieval standards, excellent communications in all directions. Since the castle garrison was completely contained, supplies could be brought up the Forth in barges to within a couple of miles of the army’s training and concentration area without fear of interruption. Additionally, the first bridge over the Forth was at Stirling. In a previous expedition, Edward I had built a pontoon bridge over the Forth and it was not impossible that Edward II might do the same. If so, news of it would come to Robert long before it was completed; this would allow him to march his army to block Edward’s crossing on the north bank. There were also tactical attractions: the terrain had good potential for a defensive action on the wooded high ground of the New Park, where Edward’s superiority in cavalry and archers would be less significant, and there was also ample dry, open terrain where Robert could drill large bodies of spearmen.

Robert’s troops were well motivated, confident, well armed and well trained. He and his commanders were totally familiar with the terrain. They had developed a series of combat manoeuvres and had instilled them into the troops, but above all, Robert had planned thoroughly. His army was positioned so that if the English gained the upper hand in the pre-battle manoeuvres, he would be able to withdraw into territory that favoured his own forces over those of his enemy, but he was also ready to seize an opportunity to accept, offer or, as it turned out, force battle on his enemy if the circumstances were favourable.

If the risks of defeat were enormous, the advantages to be gained from victory were even greater. If Edward could be decisively beaten on the battlefield, Robert’s own prestige would be secured and the final significant English-held stronghold in central Scotland would be taken without a blow being struck. Additionally, there was the prospect of taking some prominent prisoners who could then be exchanged for the various Scots in English captivity. However, there was also the question of the risks of not giving battle. Robert had been assiduous in regularly demanding military service from his subjects even though the great majority of his troops never saw action. If he continually called out men but never took them to battle the exercise would come to be seen as a waste of time and effort. In the summer of 1314, he raised the biggest force of his reign to date and avoiding battle might well have had a detrimental effect on the morale of his troops: what was the point of all that training if the king was afraid to commit himself to the sort of battle that could decide his own future and that of his kingdom? However hazardous the decision to force a battle might have been, the decision paid off handsomely and Robert’s status, both at home and abroad, was hugely enhanced by his victory.