ONE

Lifting the Veil

HOW TO SEE THE INVISIBLE

UKRAINIAN CHRISTIANS love to tell the story of how their ancestors “discovered” the liturgy. In 988, Prince Vladimir of Kiev, upon converting to the Gospel, sent emissaries to Constantinople, the capital city of Eastern Christendom. There they witnessed the Byzantine liturgy in the cathedral of Holy Wisdom, the grandest church of the East. After experiencing the chant, the incense, the icons—but, above all, the Presence—the emissaries sent word to the prince: “We did not know whether we were in heaven or on earth. Never have we seen such beauty. . . . We cannot describe it, but this much we can say: there God dwells among mankind.”

The Presence. In Greek, the word is Parousia, and it conveys one of the key themes in the Book of Revelation. In recent centuries, interpreters have used the word almost exclusively to denote Jesus' Second Coming at the end of time. That's the only definition you'll find in most English dictionaries. Yet it is not the primary meaning. Parousia's primary meaning is a real, personal, living, lasting, and active presence. In the last line of Matthew's Gospel, Jesus promises, “I will be with you always.”

In spite of our redefinitions, the Book of Revelation captures that powerful sense of Jesus' imminent Parousia—His coming that takes place right now. The Apocalypse shows us that He is here in fullness—in kingship, in judgment, in warfare, in priestly sacrifice, in Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity—whenever Christians celebrate the Eucharist.

“Liturgy is anticipated Parousia, the “already' entering our “not yet,' ” wrote Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. When Jesus comes again at the end of time, He will not have a single drop more glory than He has right now upon the altars and in the tabernacles of our churches. God dwells among mankind, right now, because the Mass is heaven on earth.

FOR THE RECORD

I want to make clear that this idea—the idea behind this book—is nothing new, and it's certainly not mine. It's as old as the Church, and the Church has never let go of it, though the idea has been lost in the shuffle of doctrinal controversies over the last several centuries.

Nor can we dismiss such talk as the pious wishes of a handful of saints and scholars. For the idea of the Mass as “heaven on earth” is now the explicit teaching of the Catholic faith. You'll find it in several places, for example, in the most fundamental statement of Catholic belief, the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

Christ, indeed, always associates the Church with Himself in this great work [the liturgy] in which God is perfectly glorified and men are sanctified. The Church is His beloved Bride who calls to her Lord and through Him offers worship to the eternal Father . . . [worship] which participates in the liturgy of heaven (no. 1089).

Our liturgy participates in the liturgy of heaven! That's in the Catechism! And there's more:

Liturgy is an “action” of the whole Christ . . . Those who even now celebrate it without signs are already in the heavenly liturgy . . . (no. 1136).

At Mass, we're already in heaven! That's not just me saying so, or a handful of dead theologians. The Catechism says so. The Catechism also quotes the very passage from Vatican II that affected me so powerfully in the months before my conversion to the Catholic faith:

In the earthly liturgy we share in a foretaste of that heavenly liturgy which is celebrated in the Holy City of Jerusalem toward which we journey as pilgrims, where Christ is sitting at the right hand of God, Minister of the sanctuary and of the true tabernacle. With all the warriors of the heavenly army we sing a hymn of glory to the Lord . . . (no. 1090).

Warriors, hymns, and holy cities. Now, that's beginning to sound like the Book of Revelation, isn't it? Well, let the Catechism bring it on home:

The Revelation of “what must soon take place,” the Apocalypse, is borne along by the songs of the heavenly liturgy . . . [T]he Church on earth also sings these songs with faith in the midst of trial . . . (no. 2642).

All of this the Catechism states matter-of-factly, as if it should be self-evident. Yet, for me, the realization has been life-changing. To my friends and colleagues, too—and anyone else I can corner for long enough to deliver a monologue—this idea, that the Mass is “heaven on earth,” arrives as news, very good news.

LORD JESUS, COME IN GLORY

If we want to see the liturgy as Prince Vladimir's emissaries saw it, we must learn to see the Apocalypse as the Church sees it. If we want to make sense of the Apocalypse, we have to learn to read it with a sacramental imagination. When we look into these matters once again, now with new eyes of faith, we will see the sense amid the strangeness in the Book of Revelation, we will see the glory hidden in the mundane in next Sunday's Mass.

Look again and discover that the golden thread of liturgy is what holds together the apocalyptic pearls of John's vision:

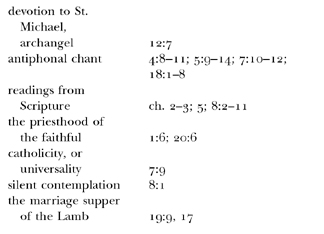

Taken together, these elements comprise much of the Apocalypse—and most of the Mass. Other liturgical elements in Revelation are easier for modern readers to miss. For example, few people today know that trumpets and harps were the standard instruments for liturgical music in John's day, as organs are today in the West. And throughout John's vision, the angels and Jesus pronounce blessings using standard liturgical formulas: “Blessed is he who . . .” If you go back and read Revelation end to end, you'll also notice that all of God's great historical interventions—plagues, wars, and so on—follow closely upon liturgical actions: hymns, doxologies, libations, incensing.

Yet, the Mass is not just in selected small details. It's in the grand scheme, too. We can see, for instance, that the Apocalypse, like the Mass, divides rather neatly in half. The first eleven chapters concern themselves with the proclamation of the letters to the seven churches and the opening of the scroll. This emphasis on “readings” makes Part One a close match for the Liturgy of the Word. Significantly, the first three chapters of Revelation mark a sort of Penitential Rite; in the seven letters to the churches, Jesus uses the word “repent” eight times. For me, this recalls the words of the ancient Didache, the liturgical manual of the first century: “first confess your transgressions, that your sacrifice may be pure.” Even John's opening assumes that the book will be read aloud by a lector within the liturgical assembly: “Blessed is he who reads aloud the words of this prophecy, and blessed are those who hear” (Rev 1:3).

Revelation's second half begins in chapter 11 with the opening of God's temple in heaven, and culminates in the pouring of the seven chalices and the marriage supper of the Lamb. With the opening of heaven, the chalices, and the banquet, Part Two offers a striking image of the Liturgy of the Eucharist.

EXTRASENSORY CENSERS?

In the Apocalypse, John depicts celestial scenes in graphic, earthly terms, and we have every right to ask why. Why depict spiritual worship—which certainly doesn't involve harps or censers—with such vivid sensory impressions? Why not use mathematical figures, as other ancient mystics did, so that readers would understand the truly esoteric, transcendent, and immaterial nature of heavenly worship?

I suspect that God revealed heavenly worship in earthly terms so that humans—who, for the first time, were invited to participate in heavenly worship—would know how to do it. I'm not saying that the Church sat around waiting for the Apocalypse to drop from heaven, so that Christians would know how to worship. No, the Apostles and their successors had been celebrating the liturgy since Pentecost, at least. Yet neither is Revelation merely an echo of a liturgy already established, a projection into heaven of what's happening on earth.

Revelation is an unveiling; that's the literal meaning of the Greek word apokalypsis. The book is a visionary reflection that reveals a norm. With the destruction of Jerusalem, the Church was definitively leaving behind a beautiful temple, a holy city, and a venerable priesthood. Yes, Christians were embracing a New Covenant, which somehow concluded the old, but somehow also included the old. What should they bring with them, from the old worship to the new? What should they leave behind? Revelation gave them guidance.

Some things had been clearly replaced in the new dispensation. Israel marked its covenant by circumcising male children on the eighth day; the Church sealed the New Covenant by baptism. Israel celebrated the sabbath as a day of rest and worship; the Church celebrated the Lord's day, Sunday, the day of resurrection. Israel recalled the old Passover once a year; the Church reenacted the definitive Passover of Jesus Christ in its celebration of the Eucharist.

Yet Jesus did not intend to do away with all that was in the Old Covenant; that's why He established a Church. He came to intensify, internationalize, and internalize the worship of Israel. Thus, the incarnation invested many of the trappings of the Old Covenant with greater capacities. For example, there would no longer be a central sanctuary on earth. Revelation shows that Christ the King is enthroned in heaven, where He acts as high priest in the Holy of Holies. But does that mean the Church can't have buildings, or officers, or candlesticks, or chalices, or vestments? No. Revelation's clear answer is that we can have all of these—all these, and heaven, too.

ZION AURA

But everyone knew where to find Jerusalem. Where would they find heaven? Apparently, not very far away from old Jerusalem. The Letter to the Hebrews says: “But you have come to Mount Zion and to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, and to innumerable angels in festal gathering, and to the assembly of the firstborn who are enrolled in heaven, and to a judge Who is God of all, and to the spirits of just men made perfect, and to Jesus, the mediator of a new covenant, and to the sprinkled blood that speaks more graciously than the blood of Abel” (Heb 12:21–24).

That little paragraph neatly summarizes the entire Apocalypse: the communion of saints and angels, the feast, the judgment, and the blood of Christ. But where does it leave us? Just where the Apocalypse did: “Then I looked, and lo, on Mount Zion stood the Lamb, and with Him a hundred and forty-four thousand who had His name and His Father's name written on their foreheads” (Rev 14:1).

All our Scriptural roads seem to lead to the city of King David, Mount Zion. God blessed Zion abundantly in the Old Covenant. “For the Lord has chosen Zion; He has desired it for His habitation: “This is my resting place forever; here I will dwell' ” (Ps 132:13–14). “I have set my king on Zion, my holy hill” (Ps 2:6). In Zion, God would establish the royal house of David, whose kingdom would last for all ages. There, God Himself would dwell forever among His people.

Remember that Zion was also the place where Jesus instituted the Eucharist, and where the Holy Spirit descended on Pentecost. Thus, the “holy hill” was even more favored in the second dispensation. The Last Supper and Pentecost were the two events that sealed the New Covenant.

Notice, too, that the remnant of Israel, the 144,000 in Revelation 14, appear on Mount Zion—though in Revelation 7 they're shown in the heavenly Jerusalem. That's an odd discrepancy. Where were they, really: on Zion or in heaven? Look again to Hebrews 12 for the answer: “you have come to Mount Zion . . . the heavenly Jerusalem.” Mount Zion is the heavenly Jerusalem, because the events that took place are what brought about the definitive union of heaven and earth.

The church on the site of these events survived the destruction of Jerusalem, but only as a sign. For the Christians of Judea, the site of the upper room was the “little church of God” dedicated to King David and St. James, the first bishop of Jerusalem. It was a “house church,” where believers met to break bread and to pray. Beyond that, however, Zion had become the living symbol of the New Covenant, and that's how it was enshrined forever in the Book of Revelation. Zion is a symbol of our earthly point of contact with heaven.

Today, even though we are thousands of miles from that little hill in Israel, we are there with Jesus in the upper room, and we are there with Jesus in heaven, whenever we go to Mass.

FIRST COMES LOVE, THEN COMES MARRIAGE

This is what was unveiled in the Book of Revelation: the union of heaven and earth, consummated in the Holy Eucharist. The first word of the book suggests as much. The term apokalypsis, usually translated as “revelation,” literally means “unveiling.” In John's time, Jews commonly used apokalypsis to describe part of their week-long wedding festivities. The apokalypsis was the lifting of the veil of a virgin bride, which took place immediately before the marriage was consummated in sexual union.

And that's what John was getting at. So close is the unity of heaven and earth that it is like the fruitful and ecstatic union of a husband and wife in love. St. Paul describes the Church as the bride of Christ (see Eph 5)—and Revelation unveils that bride. The climax of the Apocalypse, then, is the communion of the Church and Christ: the marriage supper of the Lamb (Rev 19:9). From that moment, man rises up from the earth to worship in heaven. “Then I fell down at [the angel's] feet to worship him,” John writes, “but he said to me, “You must not do that! I am a fellow servant with you and your brethren who hold the testimony of Jesus' ” (Rev 19:10). Remember that Israel's tradition always had men worshiping in imitation of angels. Now, as Revelation shows, both heaven and earth participate together in a single act of loving worship.

This apocalypse, or unveiling, points back to the cross. Matthew reports that, when Jesus died, “the curtain [or veil] of the Temple was torn in two, from top to bottom” (27:51). Thus, the sanctuary of God was “apocalypsed,” unveiled, His dwelling no longer reserved for the high priest alone. Jesus' redemption unveiled the Holy of Holies, opening God's presence to everyone. Heaven and earth could now embrace in intimate love.

THE OLD SCHOOL

The ancient liturgies were saturated with the language of heaven on earth. The Liturgy of St. James declares: “we have been counted worthy to enter into the place of the tabernacle of Your glory, and to be within the veil, and to behold the Holy of Holies.” The Liturgy of Saints Addai and Mari adds: “How awesome today is this place! For this is none other than the house of God and the gate of heaven; because You have been seen eye to eye, O Lord.”

St. Cyril of Jerusalem (fifth century) offers a profound meditation on the line “Lift up your hearts!” “For truly,” he says, “in that most awesome hour, we should have our hearts on high with God, and not below, thinking of earth and earthly things. The Priest bids all in that hour to dismiss all cares of this life, or household worries, and to have their hearts in heaven with the merciful God.”

Indeed, we must be like St. John on Patmos, when he heard the voice from heaven say, “Come up here” (see Rev 11:12). That's what it means to “Lift up your hearts!” It means to open our hearts to the heaven that's before us, just as St. John did. Lift up your hearts, then, to worship in the Spirit. For, in the liturgy, says the fourth-century Liber Graduum, “the body is a hidden temple, and the heart is a hidden altar for the ministry in Spirit.”

First, however, we must actively seek recollection. St. Cyril goes on: “But let no one come here who could say with his mouth, “We lift up our hearts unto the Lord,' but have his mind concerned with the cares of this life. At all times, God should be in our memory. But if this is impossible by reason of human frailty, we should at least make the effort in that hour.”

Put simply, we should heed the compact phrase of the Byzantine liturgy: “Wisdom! Be attentive!”

KNOCK, KNOCK

Yes, be attentive! Because Revelation is unveiling more than “information.” It's a personal invitation, intended for you and me from all eternity. The Revelation of Jesus Christ has an immediate and overwhelming impact on our lives. We are the bride of Christ unveiled; we are His Church. And Jesus wants each and every one of us to enter into the most intimate relationship imaginable with Him. He uses wedding imagery to demonstrate how much He loves us, how close He wants us to stay—and how permanent he intends our union to be.

Behold, God makes all things new. The Book of Revelation is not as strange as it seems, and the Mass is richer than we'd ever dreamed. Revelation is as familiar as the life we live; and even the dullest Mass is suddenly paved with gold and glittering jewels.

You and I need to open our eyes and rediscover this long-lost secret of the Church, the early Christians' key to understanding the mysteries of the Mass, the only true key to the mysteries of the Apocalypse. “It is in this eternal liturgy that the Spirit and the Church enable us to participate whenever we celebrate the mystery of salvation in the sacraments” (Catechism, no. 1139).

We go to heaven—not only when we die, or when we go to Rome, or when we make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. We go to heaven when we go to Mass. This is not merely a symbol, not a metaphor, not a parable, not a figure of speech. It is real. In the fourth century, St. Athanasius wrote, “My beloved brethren, it is no temporal feast that we come to, but an eternal, heavenly feast. We do not display it in shadows; we approach it in reality.”

Heaven on earth—that's reality! That's where you stood and where you dined last Sunday! What were you thinking then?

Consider what the Lord wanted you to think. Consider His invitations from the Book of Revelation: “He who has an ear, let him hear what the Spirit says to the churches. To him who conquers I will give some of the hidden manna” (2:17). What is the hidden manna? Remember the promise Jesus made when He spoke of “manna” in John's Gospel: “Your fathers ate the manna in the wilderness, and they died. This is the bread which comes down from heaven, that a man may eat of it and not die. I am the living bread which came down from heaven” (6:49–51). Manna was the daily bread of God's people during their pilgrimage in the desert. Now, Jesus is offering something greater, and He's quite specific about His invitation: “Behold, I stand at the door and knock; if anyone hears My voice and opens the door, I will come in to him and eat with him, and he with Me” (3:20).

So Jesus really does have a meal on His mind; He wants to share the hidden manna with us, and He is the hidden manna. In Revelation 4:1, we see, too, that this is more than an intimate dinner for two. Jesus had stood at the door and knocked, and now the door is open. John enters “the Spirit” to see priests, martyrs, and angels gathered around heaven's throne. With John, we discover that heaven's banquet is a family meal.

Now, with eyes of faith—and “in the Spirit”—let us begin to see that Revelation invites us to a heavenly banquet, to a love embrace, to Zion, to judgment, to battle. To Mass.