On the opposite bank of the Cross River, eight miles through the deep forest, lay the tiny village of Eshobi. I knew both the place and its inhabitants well, for on a previous trip I had made it one of my bases for a number of months. It had been a good hunting-ground, and the Eshobi people had been good hunters, so, while we were in Mamfe, I was anxious to get in touch with the villagers and see if they could get us some specimens. As the best way of obtaining information or sending messages was via the local market, I sent for Phillip, our cook. He was an engaging character, with a wide, buck-toothed smile, and a habit of walking with a stiff military gait, and standing at attention when addressed; this argued an army training, which, in fact, he had not had. He clumped up on to the verandah and stood before me as rigid as a guardsman.

‘Phillip, I want to find an Eshobi man, you hear?’ I said.

‘Yes, sah.’

‘Now, when you go for market you go find me one Eshobi man and you go bring him for here and I go give him book for take Eshobi, eh?’

‘Yes, sah.’

‘Now, you no go forget, eh? You go find me Eshobi man one time.’

‘Yes, sah,’ said Phillip, and clumped off to the kitchen. He never wasted time on unnecessary conversation.

Two days passed without an Eshobi man putting in an appearance, and, occupied with other things, I forgot the whole matter. Then, on the fourth day, Phillip appeared, clumping down the drive triumphantly with a rather frightened looking fourteen-year-old boy in tow. The lad had obviously clad himself in his best clothes for his visit to the Metropolis of Mamfe, a fetching outfit that consisted of a tattered pair of khaki shorts, and a grubby white shirt which had obviously been made out of a sack of some sort and had across its back the mysterious but decorative message ‘PRODUCE OF GR’ in blue lettering. On his head was perched a straw hat which, with age and wear, had attained a pleasant shade of pale silvery green. This reluctant apparition was dragged up on to the front verandah, and his captor stood smugly to attention with the air of one who has, after much practice, accomplished a particularly difficult conjuring trick. Phillip had a curious way of speaking which had taken me some time to understand, for he spoke pidgin very fast and in a sort of muted roar, a cross between a bassoon and a regimental sergeant-major, as though everyone in the world was deaf. When labouring under excitement he became almost incomprehensible.

‘Who is this?’ I asked, surveying the youth.

Phillip looked rather hurt. ‘Dis na man, sah,’ he roared, as if explaining something to a particularly dim-witted child. He gazed at his protégé with affection and gave the unfortunate lad a slap on the back that almost knocked him off the verandah.

‘I can see it’s a man,’ I said patiently, ‘but what does he want?’

Phillip frowned ferociously at the quivering youth and gave him another blow between the shoulder blades.

‘Speak now,’ he blared, ‘speak now, Masa de wait.’

We waited expectantly. The youth shuffled his feet, twiddled his toes in an excess of embarrassment, gave a shy, watery smile and stared at the ground. We waited patiently. Suddenly he looked up, removed his headgear, ducked his head and said: ‘Good morning, sah,’ in a faint voice.

Phillip beamed at me as if this greeting were sufficient explanation for the lad’s presence. Deciding that my cook had not been designed by nature to play the part of a skilled and tactful interrogator, I took over myself.

‘My friend,’ I said, ‘how dey de call you?’

‘Peter, sah,’ he replied miserably.

‘Dey de call um Peter, sah,’ bellowed Phillip, in case I should have been under any misapprehension.

‘Well, Peter, why you come for see me?’ I inquired.

‘Masa, dis man your cook ’e tell me Masa want some man for carry book to Eshobi,’ said the youth aggrievedly.

‘Ah! You be Eshobi man?’ I asked, light dawning.

‘Yes, sah.’

‘Phillip,’ I said, ‘you are a congenital idiot.’

‘Yes, sah,’ agreed Phillip, pleased with this unsolicited testimonial.

‘Why you never tell me dis be Eshobi man?’

‘Wah!’ gasped Phillip, shocked to the depths of his sergeant-major’s soul, ‘but I done tell Masa dis be man.’

Giving Phillip up as a bad job I turned back to the youth.

‘Listen, my friend, you savvay for Eshobi one man dey de call Elias?’

‘Yes, sah, I savvay um.’

‘All right. Now you go tell Elias dat I done come for Cameroon again for catch beef, eh? You go tell um I want um work hunter man again for me, eh? So you go tell um he go come for Mamfe for talk with me. You go tell um, say, dis Masa ’e live for U.A.C. Masa’s house, you hear?’

‘I hear, sah.’

‘Right, so you go walk quick-quick to Eshobi and tell Elias, eh? I go dash you dis cigarette so you get happy when you walk for bush.’

He received the packet of cigarettes in his cupped hands, ducked his head and beamed at me.

‘Tank you, Masa,’ he said.

‘All right … go for Eshobi now. Walka good.’

‘Tank you, Masa,’ he repeated, and stuffing the packet into the pocket of his unorthodox shirt he trotted off down the drive.

Twenty-four hours later Elias arrived. He had been one of my permanent hunters when I had been in Eshobi, so I was delighted to see his fat, waddling form coming down the drive towards me, his Pithecanthropic features split into a wide grin of glad recognition. Our greetings over, he solemnly handed me a dozen eggs carefully wrapped in banana leaves, and I reciprocated with a carton of cigarettes and a hunting knife I had brought out from England for that purpose. Then we got down to the serious business of talking about beef. First he told me about all the beef he had hunted and captured in my eight years’ absence, and how my various hunter friends had got on. Old N’ago had been killed by a bush-cow; Andraia had been bitten in the foot by a water beef; Samuel’s gun had exploded and blown a large portion of his arm away (a good joke, this), while just recently John had killed the biggest bush-pig they had ever seen, and sold the meat for over two pounds. Then, quite suddenly, Elias said something that riveted my attention.

‘Masa remember dat bird Masa like too much?’ he inquired in his husky voice.

‘Which bird, Elias?’

‘Dat bird ’e no get bere-bere for ’e head. Last time Masa live for Mamfe I done bring um two picken dis bird.’

‘Dat bird who make his house with potta-potta? Dat one who get red for his head?’ I asked excitedly.

‘Yes, na dis one,’ he agreed.

‘Well, what about it?’ I said.

‘When I hear Masa done come back for Cameroons I done go for bush for look dis bird,’ Elias explained. ‘I remember dat Masa ’e like dis bird too much. I look um, look um for bush for two, three days.’

He paused and looked at me, his eyes twinkling.

‘Well?’

‘I done find um, Masa,’ he said, grinning from ear to ear.

‘You find um?’ I could scarcely believe my luck. ‘Which side ’e dere … which side ’e live … how many you see … what kind of place … ?’

‘’E dere dere,’ Elias went on, interrupting my flow of feverish questions, ‘for some place ’e get big big rock. ’E live for up hill, sah. ’E get ’e house for some big rock.’

‘How many house you see?’

‘I see three, sah. But ’e never finish one house, sah.’

‘What’s all the excitement about?’ inquired Jacquie, who had just come out on to the verandah.

‘Picathartes,’ I said succinctly, and to her credit she knew exactly what I was talking about.

Picathartes was a bird that, until a few years ago, was known only from a few museum skins, and had been observed in the wild state by perhaps two Europeans. Cecil Webb, then the London Zoo’s official collector, managed to catch and bring back alive the first specimen of this extraordinary bird. Six months later, when in the Cameroons, I had two adult specimens brought in to me, but these had unfortunately died on the voyage home of aspergillosis, a particularly virulent lung disease. Now Elias had found a nesting colony of them and it seemed we might, with luck, be able to get some fledglings and hand-rear them.

‘Dis bird, ’e get picken for inside ’e house?’ I asked Elias.

‘Sometime ’e get, sah,’ he said doubtfully. ‘I never look for inside de house. I fear sometime de bird go run.’

‘Well,’ I said, turning to Jacquie, ‘there’s only one thing to do, and that’s to go to Eshobi and have a look. You and Sophie hang on here and look after the collection; I’ll take Bob and spend a couple of days there after Picathartes. Even if they haven’t got any young I would like to see the thing in its wild state.’

‘All right. When will you go?’ asked Jacquie.

‘Tomorrow, if I can arrange carriers. Give Bob a shout and tell him we’re really going into the forest at last. Tell him to sort out his snake-catching equipment.’

Early the next morning, when the air was still comparatively cool, eight Africans appeared outside John Henderson’s house, and, after the usual bickering as to who should carry what, they loaded our bundles of equipment on to their woolly heads and we set off for Eshobi. Having crossed the river, our little cavalcade made its way across the grassfield, where our abortive python hunt occurred, and on the opposite side we plunged into the mysterious forest. The Eshobi path lay twisting and turning through the trees in a series of intricate convolutions that would have horrified a Roman road-builder. Sometimes it doubled back on itself to avoid a huge rock, or a fallen tree, and at other times it ran as straight as a rod through all such obstacles, so that our carriers were forced to stop and form a human chain to lift the loads over a tree trunk, or lower them down a small cliff.

I had warned Bob that we would see little, if any, wild life on the way, but this did not prevent him from attacking every rotten tree trunk we passed, in the hopes of unearthing some rare beast from inside it. I am so tired of hearing and reading about the dangerous and evil tropical forest, teeming with wild beasts. In the first place it is about as dangerous as the New Forest in midsummer, and in the second place it does not teem with wild life; every bush is not aquiver with some savage creature waiting to pounce. The animals are there, of course, but they very sensibly keep out of your way. I defy anyone to walk through the forest to Eshobi, and, at the end of it, be able to count on the fingers of both hands the ‘wild beasts’ he has seen. How I wish these descriptions were true. How I wish that every bush did contain some ‘savage denizen of the forest’ lurking in ambush. A collector’s job would be so much easier.

The only wild creatures at all common along the Eshobi path were butterflies, and these, obviously not having read the right books, showed a strong disinclination to attack us. Whenever the path dipped into a small valley, a tiny stream would lie at the bottom, and on the damp, shady banks alongside the clear waters the butterflies would be sitting in groups, their wings opening and closing slowly, so that from a distance areas of the stream banks took on an opalescent quality, changing from flame red to white, from sky blue to mauve and purple, as the insects – in a sort of trance – seemed to be applauding the cool shade with their wings. The brown, muscular legs of the carriers would tramp through them unseeingly, and suddenly we would be waist-high in a swirling merry-go-round of colour as the butterflies dipped and wheeled around us and then, when we had passed, settled again on the dark soil which was as rich and moist as a fruit cake, and just as fragrant.

One vast and ancient tree marked the half-way point on the Eshobi road, a tree so tangled in a web of lianas as to be almost invisible. This was a resting place, and the carriers, grunting and exhaling their breath sharply through their front teeth in a sort of exhausted whistle, lowered their loads to the ground and squatted beside them, the sweat glistening on their bodies. I handed round cigarettes and we sat and enjoyed them quietly: in the dim, cathedral-like gloom of the forest there was no breeze, and the smoke rose in straight, swaying blue columns into the air. The only sounds were the incessant, circular-saw songs of the great green cicadas clinging to every tree, and, in the distance, the drunken honking of a flock of hornbills.

As we smoked we watched some of the little brown forest skinks hunting among the roots of the trees around us. These little lizards always looked neat and shining, as though they had been cast in chocolate and had just that second stepped out of the mould, gleaming and immaculate. They moved slowly and deliberately, as if they were afraid of getting their beautiful skins dirty. They peered from side to side with bright eyes as they slid through their world of brown, dead leaves, forests of tiny toadstools and lawns of moss that padded the stones like a carpet. Their prey was the immense population of tiny creatures that inhabited the forest floor, the small black beetles hurrying along like undertakers late for a funeral, the slow, smooth-sliding slugs, weaving a silver filigree of slime over the leaves, and the small, nut-brown crickets who squatted in the shadows waving their immensely long antennae to and fro, like amateur fishermen on the banks of a stream.

Among the dark, damp hollows between the buttress roots of the great tree under which we sat there were small clusters of an insect which had never failed to fascinate me. They looked like a small daddy-longlegs in repose, but with opaque, misty-white wings. They sat there in groups of about ten, trembling their wings gently, and moving their fragile legs up and down like restive horses. When disturbed they all took to the air and started a combined operation which was quite extraordinary to watch. They rose about eight inches above the ground, formed a circle in an area that could be covered by a saucer and then began to fly round and round very rapidly, some going up and over, as it were, while the others swept round and round like a wheel. The effect from a distance was rather weird, for they resembled a whirling ball of shimmering misty white, changing its shape slightly at intervals, but always maintaining exactly the same position in the air. They flew so fast, and their bodies were so slender, that all you could see was this shimmer of frosty wings. I am afraid that this aerial display intrigued me so much that I used to go out of my way, when walking in the forest, to find groups of these insects and disturb them so that they would dance for me.

Eventually we reached Eshobi at mid-day, and I found it had changed little from the days when I had been there eight years before. There was still the same straggle of dusty thatched huts in two uneven rows, with a wide area of dusty path lying between them that served as the village high street, a playground for children and dogs and a scratching ground for the scrawny fowls. Elias came waddling down this path to greet us, picking his way carefully through the sprawling mass of babies and livestock, followed by a small boy carrying two large green coconuts on his head.

‘Welcome, Masa, you done come?’ he called huskily.

‘Iseeya, Elias,’ I replied.

He grinned at us delightedly, as the carriers, still grunting and whistling, deposited our equipment all over the village street.

‘Masa go drink dis coconut?’ Elias asked hopefully, waving his machete about.

‘Yes, we like um too much,’ I said, regarding the huge nuts thirstily.

Elias bustled into activity. From the nearest hut were brought two dilapidated chairs, and Bob and I were seated in a small patch of shade in the centre of the village street, surrounded by a crowd of politely silent but deeply fascinated Eshobites. With quick, accurate strokes of his machete Elias stripped away the thick husk from the coconut. When the tips of the nuts were exposed he gave each of them a swift slice with the end of his machete-blade, and then handed them to us, each neatly trepanned so that we could drink the cool, sweet juice inside. In each nut there was about two and a half glassfuls of this thirst-quenching, hygienically sealed nectar, and we savoured every mouthful.

After the rest, our next job was to get the camp in order. Two hundred yards from the village there was a small stream, and on its banks we chose an area that would not be too difficult to clear. A group of men armed with machetes set to work to cut down all the small bushes and saplings, while another group followed behind with short-handled, broad-bladed hoes, in an effort to level the red earth. At length, after the usual African uproar of insults, accusations of stupidity, sit-down strikes and minor brawls, the area had been worked over so that it resembled a badly ploughed field, and we could get the tents up. While a meal was being prepared we went down to the stream and washed the dirt and sweat from our bodies in the icy waters, watching the pink-and-brown crabs waving their pincers to us from among the rocks, and feeling the tiny, brilliant blue-and-red fish nibbling gently at our feet. We wended our way back to camp, feeling refreshed, and found some sort of organization reigning. When we had eaten, Elias came and squatted in the shade of our lean-to tent, and we discussed hunting plans.

‘What time we go look dis bird, Elias?’

‘Eh, Masa savvay now ’e be hot too much. For dis time dis bird ’e go look for chop for bush. For evening time when it get cold ’e go for dis ’e house for work, and den we go see um.’

‘All right, then you go come back for four o’clock time, you hear? Then we go look dis bird, eh?’

‘Yes, sah,’ said Elias, rising to his feet.

‘And if you no speak true, if we never see dis bird, if you’ve been funning me I go shoot you, bushman, you hear?’

‘Eh!’ he exclaimed, chuckling, ‘I never fun with Masa, for true, sah.’

‘All right, we go see you, eh?’

‘Yes, sah,’ he said, as he twisted his sarong round his ample hips and padded off towards the village.

At four o’clock the sun had dipped behind the tallest of the forest trees, and the air had the warm, drowsy stillness of evening. Elias returned, wearing, in place of his gaudy sarong, a scrap of dirty cloth twisted round his loins. He waved his machete nonchalantly.

‘I done come, Masa,’ he proclaimed. ‘Masa ready?’

‘Yes,’ I said, shouldering my field-glasses and collecting bag. ‘Let’s go, hunter man.’

Elias led us down the dusty main street of the village, and then branched off abruptly down a narrow alley-way between the huts. This led us into a small patch of farmland, full of feathery cassava bushes and dusty banana plants. Presently, the path dipped across a small stream and then wound its way into the forest. Before we had left the village street Elias had pointed out a hill to me which he said was the home of Picathartes, and although it had looked near enough to the village, I knew better than to believe it. The Cameroon forest is like the Looking-glass Garden. Your objective seems to loom over you, but as you walk towards it, it appears to shift position. At times, like Alice, you are forced to walk in the opposite direction in order to get there.

And so it was with this hill. The path, instead of making straight for it, seemed to weave to and fro through the forest in the most haphazard fashion, until I began to feel I must have been looking at the wrong hill when Elias had pointed it out to me. At that moment, however, the path started to climb in a determined manner, and it was obvious that we had reached the base of the hill. Elias left the path and plunged into the undergrowth on one side, hacking his way through the overhanging lianas and thorn bushes with his machete, hissing softly through his teeth, his feet spreading out in the soft leaf mould without a sound. In a very short time we were plodding up a slope so steep that, on occasions, Elias’ feet were on a level with my eyes.

Most hills and mountains in the Cameroons are of a curious and exhausting construction. Created by ancient volcanic eruption, they had been pushed skywards viciously by the massive underground forces, and this has formed them in a peculiar way. They are curiously geometrical, some perfect isosceles triangles, some acute angles, some cones and some box-shaped. They rear up in such a bewildering variety of shapes that it would have been no surprise to see a cluster of them demonstrating one of the more spiky and incomprehensible of Euclid’s theorems.

The hill whose sides we were now assaulting reared up in an almost perfect cone. After you had been climbing for a bit you began to gain the impression that it was much steeper than it had first appeared, and within a quarter of an hour you were convinced that the surface sloped at the rate of one in one. Elias went up it as though it were a level macadam road, ducking and weaving skilfully between the branches and overhanging undergrowth, while Bob and I, sweating and panting, struggled along behind, sometimes on all fours, in an effort to keep pace with him. Then, to our relief, just below the crest of the hill, the ground flattened out into a wide ledge, and through the tangle of trees we could see, ahead of us, a fifty-foot cliff of granite, patched with ferns and begonias, with a tumbled mass of giant, water-smoothed boulders at its base.

‘Dis na de place, Masa,’ said Elias, stopping and lowering his fat bottom on to a rock.

‘Good,’ said Bob and I in unison, and sat down to regain our breath.

When we had rested, Elias led us along through the maze of boulders to a place where the cliff face sloped outwards, overhanging the rocks below. We moved some little way along under this overhang, and then Elias stopped suddenly.

‘Dere de house, Masa,’ he said, his fine teeth gleaming in a grin of pride. He was pointing up at the rock face, and I saw, ten feet above us, the nest of a Picathartes.

At first glance it resembled a huge swallow’s nest, made out of reddish-brown mud and tiny rootlets. At the base of the nest longer roots and grass stalks had been woven into the earth so that they hung down in a sort of beard; whether this was just untidy workmanship on the part of the bird, or whether it was done for reasons of camouflage, was difficult to judge. Certainly the trailing beard of roots and grass did disguise the nest, for, at first sight, it resembled nothing more than a tussock of grass and mud that had become attached to the gnarled, water-ribbed surface of the cliff. The whole nest was about the size of a football and this position under the overhang of the cliff nicely protected it from any rain.

Our first task was to discover if the nest contained anything. Luckily a tall, slender sapling was growing opposite, so we shinned up this in turn and peered into the inside of the nest. To our annoyance it was empty, though ready to receive eggs, for it had been lined with fine roots woven into a springy mat. We moved a little way along the cliff and soon came upon two more nests, one complete like the first one, and one half finished. But there was no sign of young or eggs.

‘If we go hide, small time dat bird go come, sah,’ said Elias.

‘Are you sure?’ I asked doubtfully.

‘Yes, sah, for true, sah.’

‘All right, we’ll wait small time.’

Elias took us to a place where a cave had been scooped out of the cliff, its mouth almost blocked by an enormous boulder, and we crouched down behind this natural screen. We had a clear view of the cliff face where the nests hung, while we ourselves were in shadow and almost hidden by the wall of stone in front of us. We settled down to wait.

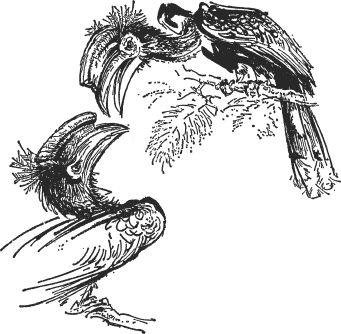

The forest was getting gloomy now, for the sun was well down. The sky through the tangle of leaves and lianas above our heads was green flecked with gold, like the flanks of an enormous dragon seen between the trees. Now the very special evening noises had started. In the distance we could hear the rhythmic crash of a troupe of mona monkeys on their way to bed, leaping from tree to tree, with a sound like great surf on a rocky shore, punctuated by occasional cries of ‘Oink … Oink …’ from some member of the troupe. They passed somewhere below us along the base of the hill, but the undergrowth was too thick for us to see them. Following them came the usual retinue of hornbills, their wings making fantastically loud whooping noises as they flew from tree to tree. Two of them crashed into the branches above us and sat there silhouetted against the green sky, carrying on a long and complicated conversation, ducking and swaying their heads, great beaks gaping, whining and honking hysterically at each other. Their fantastic heads, with the great beaks and sausage-shaped casques lying on top, bobbing and mowing against the sky, looked like some weird devil-masks from a Ceylonese dance.

The perpetual insect orchestra had increased a thousandfold with the approach of darkness, and the valley below us seemed to vibrate with their song. Somewhere a tree-frog started up, a long, trilling note, followed by a pause, as though he were boring a hole through a tree with a miniature pneumatic drill, and had to pause now and then to let it cool. Suddenly I heard a new noise. It was a sound I had never heard before and I glanced inquiringly at Elias. He had stiffened, and was peering into the gloomy net of lianas and leaves around us.

‘Na whatee dat?’ I whispered.

‘Na de bird, sah.’

The first cry had been quite far down the hill, but now came another cry, much closer. It was a curious noise which can only be described, rather inadequately, as similar to the sudden sharp yap of a pekinese, but much more flute-like and plaintive. Again it came, and again, but we still could not see the bird, though we strained our eyes in the gloom.

‘D’you think it’s Picathartes?’ whispered Bob.

‘I don’t know … It’s a noise I haven’t heard before.’

There was a pause, and then suddenly the cry was repeated, very near now, and we lay motionless behind our rock. Not far in front of our position grew a thirty-foot sapling, bent under the weight of a liana as thick as a bell-rope that hung in loops around it, its main stem hidden in the foliage of some near-by tree. While the rest of the area we could see was gloomy and ill-defined, this sapling, lovingly entwined by its killer liana, was lit by the last rays of the setting sun, so that the whole setting was rather like a meticulous backcloth. And, as though a curtain had gone up on this miniature stage, a real live Picathartes suddenly appeared before us.

I say suddenly and I mean it. Animals and birds in a tropical forest generally approach so quietly that they appear before you suddenly, unexpectedly, as if dropped there by magic. The thick liana fell in a huge loop from the top of the sapling, and on this loop the bird materialized, swaying gently on its perch, its head cocked on one side as if listening. Seeing any wild animal in its natural surroundings is a thrill, but to watch something that you know is a great rarity, something that you know has only been seen by a handful of people before you, gives the whole thing an added excitement and spice. So Bob and I lay there staring at the bird with the ardent, avid expressions of a couple of philatelists who have just discovered a penny black in a child’s stamp album.

The Picathartes was about the size of a jackdaw, but its body had the plump, sleek lines of a blackbird. Its legs were long and powerful, and its eyes large and obviously keen. The breast was a delicate creamy-buff and the back and long tail a beautiful slate grey, pale and powdery-looking. The edge of the wing was black and this acted as a dividing-line that showed up wonderfully the breast and back colours. But it was the bird’s head that caught the attention and held it. It was completely bare of feathers: the forehead and top of the head were a vivid sky blue, the back a bright rose-madder pink, while the sides of the head and the cheeks were black. Normally a bald-headed bird looks rather revolting, as if it were suffering from some unpleasant and incurable disease, but Picathartes looked splendid with its tricoloured head, as if wearing a crown.

After the bird had perched on the liana for a minute or so it flew down on to the ground, and proceeded to work its way to and fro among the rocks in a series of prodigious leaps, quite extraordinary to watch. They were not ordinary bird-like hops, for Picathartes was projected into the air as if those powerful legs were springs. It disappeared from view among the rocks, and we heard it call. It was answered almost at once from the top of the cliff, and looking up we could see another Picathartes on a branch above us, peering down at the nests on the cliff face. Suddenly it spiralled downwards and alighted on the edge of one of the nests, paused a moment to look about, and then leaned forward to tidy up a hair-like rootlet that had become disarranged. Then the bird leaped into the air – there was no other way to describe it – and swooped down the hill into the gloomy forest. The other emerged from among the rocks and flew after it, and in a short time we heard them calling to each other plaintively among the trees.

‘Ah,’ said Elias, rising and stretching himself, ‘’e done go.’

‘’E no go come back?’ I asked, pummelling my leg, which had gone to sleep.

‘No, sah. ’E done go for inside bush, for some big stick where ’e go sleep. Tomorrow ’e go come back for work dis ’e house.’

‘Well, we might as well go back to Eshobi then.’

Our progress down the hill was a much speedier affair than our ascent. It was now so dark under the canopy of trees that we frequently missed our footing and slid for considerable distances on our backsides, clutching desperately at trees and roots as we passed in an effort to slow down. Eventually we emerged in the Eshobi high street bruised, scratched and covered with leaf mould. I was filled with elation at having seen a live Picathartes, but, at the same time, depressed by the thought that we could not hope to get any of the youngsters. It was obviously useless hanging around in Eshobi, so I decided we would set off again for Mamfe the next day, and try to do a little collecting as we passed through the forest. One of the most successful ways of collecting animals in the Cameroons is to smoke out hollow trees, and on our way to Eshobi I had noticed several huge trees with hollow insides, which I thought might well repay investigation.

Early the next morning we packed up our equipment, and sent the carriers off with it. Then, accompanied by Elias and three other Eshobi hunters, Bob and I followed at a more leisurely pace.

The first tree was three miles into the forest, lying fairly close to the edge of the Eshobi road. It was a hundred and fifty feet high, and the greater part of its trunk was as hollow as a drum. There is quite an art to smoking out a hollow tree. It is a prolonged and sometimes complicated process. Before going to all the trouble of smoking a tree the first thing to do, if possible, is to ascertain whether or not there is anything inside worth smoking out. If the tree has a large hole at the base of the trunk, as most of them do, this is a relatively simple matter. You simply stick your head inside and get somebody to beat the trunk with a stick. If there are any animals inside you will hear them moving about uneasily after the reverberations have died away, and even if you can’t hear them you can be assured of their presence by the shower of powdery rotten wood that will come cascading down the trunk. Having discovered that there is something inside the tree the next job is to scan the top part of the trunk with field-glasses and try and spot all exit holes, which then have to be covered with nets. When this has been done, a man is stationed up the tree to retrieve any creature that gets caught up there, the holes at the base of the trunk are stopped. You then light a fire, and this is the really tricky part of the operation, for the inside of these trees is generally dry and tinder-like, and if you are not careful you can set the whole thing ablaze. So first of all you kindle a small bright blaze with dry twigs, moss and leaves, and when this is well alight you carefully cover it with ever-increasing quantities of green leaves, so that the fire no longer blazes but sends up a sullen column of pungent smoke, which is sucked up the hollow barrel of the tree exactly as if it were a chimney. After this anything can happen and generally does, for these hollow trees often contain a weird variety of inhabitants, ranging from spitting cobras to civet cats, from bats to giant snails; half the charm and excitement of smoking out a tree is that you are never quite sure what is going to appear next.

The first tree we smoked was not a wild success. All we got was a handful of leaf-nosed bats with extraordinary gargoyle-like faces, three giant millipedes that looked like Frankfurter sausages with a fringe of legs underneath and a small grey dormouse which bit one of the hunters in the thumb and escaped. So we removed the nets, put out the fire and proceeded on our way. The next hollow tree was considerably taller and of tremendous girth. At its base was an enormous split in the trunk shaped like a church door, and four of us could stand comfortably in the gloomy interior of the trunk. Peering up the hollow barrel of the trunk and beating on the wood with a machete we were rewarded by vague scuffling noises from above, and a shower of powdery rotten wood fell on our upturned faces and into our eyes. Obviously the tree contained something. Our chief problem was to get a hunter to the top of the tree to cover the exit holes, for the trunk swept up about a hundred and twenty feet into the sky as smooth as a walking-stick. Eventually, we joined all three of our rope-ladders together, and tied a strong, light rope to one end. Then, weighting the rope end, we hurled it up and into the forest canopy until our arms ached, until at last it fell over a branch and we could haul the ladders up into the sky and secure them. So, when the nets were fixed in position at the top and bottom of the tree, we lit the fire at the base of the trunk and stood back to await results.

Generally one had to wait four or five minutes for the smoke to percolate to every part of the tree before one got any response, but in this particular case the results were almost immediate. The first beasts to appear were those nauseating-looking creatures called whip-scorpions. They cover, with their long angular legs, the area of a soup plate, and they look like a nightmare spider that has been run over by a steamroller and reduced to a paperlike thickness. This enables them to slide in and out of crevices, that would allow access to no other beast, in a most unnerving manner. Apart from this they could glide about over the surface of the wood as though it were ice, and at a speed that was quite incredible. It was this speedy and silent movement, combined with such a forest of legs, that made them so repulsive, and made one instinctively shy away from them, even though one knew they were harmless. So, when the first one appeared magically out of a crack and scuttled over my bare arm as I leant against the tree, it produced an extraordinary demoralizing effect, to say the least.

I had only just recovered from this when all the other inhabitants of the tree started to vacate in a body. Five fat grey bats flapped out into the nets, where they hung chittering madly and screwing up their faces in rage. They were quickly joined by two green forest squirrels with pale fawn rings round their eyes, who uttered shrill grunts of rage as they rolled about in the meshes of the nets while we tried to disentangle them without getting bitten. They were followed by six grey dormice, two large greeny rats with orange noses and behinds, and a slender green tree-snake with enormous eyes, who slid calmly through the meshes of the nets with a slightly affronted air, and disappeared into the undergrowth before anyone could do anything sensible about catching him. The noise and confusion was incredible: Africans danced about through the billowing smoke, shouting instructions of which nobody took the slightest notice, getting bitten with shrill yells of agony, stepping on each other’s feet, wielding machetes and sticks with gay abandon and complete disregard for safety. The man posted in the top of the tree was having fun on his own, and was shouting and yelling and leaping about in the branches with such vigour that I expected to see him crash to the forest floor at any moment. Our eyes streamed, our lungs were filled with smoke, but the collecting bags filled up with a wiggling, jumping cargo of creatures.

Eventually the last of the tree’s inhabitants had appeared, the smoke had died down and we could pause for a cigarette and to examine each other’s honourable wounds. As we were doing this the man at the top of the tree lowered down two collecting bags on the end of long strings, before preparing to return to earth himself. I took the bags gingerly, not knowing what the contents were, and inquired of the stalwart at the top of the tree how he had fared.

‘What you get for dis bag?’ I inquired.

‘Beef, Masa,’ he replied intelligently.

‘I know it’s beef, bushman, but what kind of beef you get?’

‘Eh! I no savvay how Masa call um. ’E so so rat, but ’e get wing. Dere be one beef for inside ’e get eye big big like man, sah.’

I was suddenly filled with an inner excitement.

‘’E get hand like rat or like monkey?’ I shouted.

‘Like monkey, sah.’

‘What is it?’ asked Bob with interest, as I fumbled with the string round the neck of the bags.

‘I’m not sure, but I think it’s a bushbaby … if it is it can only be one of two kinds, and both of them are rare.’

I got the string off the neck of the bag after what seemed an interminable struggle, and cautiously opened it. Regarding me from inside it was a small, neat grey face with huge ears folded back like fans against the side of the head, and two enormous golden eyes, that looked at me with the horror-stricken expression of an elderly spinster who had discovered a man in the bathroom cupboard. The creature had large, human-looking hands, with long, slender bony fingers. Each of these, except the forefinger, was tipped with a small, flat nail that looked as though it had been delicately manicured, while the forefinger possessed a curved claw that looked thoroughly out of place on such a human hand.

‘What is it?’ asked Bob in hushed tones, seeing that I was gazing at the creature with an expression of bliss on my face.

‘This,’ I said ecstatically, ‘is a beast I have tried to get every time I’ve been to the Cameroons. Euoticus elegantulus, or better known as a needle-clawed lemur or bushbaby. They’re extremely rare, and if we succeed in getting this one back to England it will be the first ever to be brought back to Europe.’

‘Gosh,’ said Bob, suitably impressed.

I showed the little beast to Elias.

‘You savvay dis beef, Elias?’

‘Yes, sah, I savvay um.’

‘Dis kind of beef I want too much. If you go get me more I go pay you one one pound. You hear.’

‘I hear, sah. But Masa savvay dis kind of beef ’e come out for night time. For dis kind of beef you go look um with hunter light.’

‘Yes, but you tell all people of Eshobi I go pay one one pound for dis beef, you hear?’

‘Yes, sah. I go tell um.’

‘And now,’ I said to Bob, carefully tying up the bag with the precious beef inside, ‘let’s get back to Mamfe quick and get this into a decent cage where we can see it.’

So we packed up the equipment and set off at a brisk pace through the forest towards Mamfe, pausing frequently to open the bag and make sure that the precious specimen had got enough air, and had not been spirited away by some frightful juju. We reached Mamfe at lunch-time and burst into the house, calling to Jacquie and Sophie to come and see our prize. I opened the bag cautiously and Euoticus edged its head out and surveyed us all in turn with its enormous, staring eyes.

‘Oh, isn’t it sweet,’ said Jacquie.

‘Isn’t it a dear?’ said Sophie.

‘Yes,’ I said proudly, ‘it’s a …’

‘What shall we call it?’ asked Jacquie.

‘We’ll have to think of a good name for it,’ said Sophie.

‘It’s an extremely rare …’ I began.

‘How about Bubbles?’ suggested Sophie.

‘No, it doesn’t look like a Bubbles,’ said Jacquie surveying it critically.

‘It’s an Euoticus …’

‘How about Moony?’

‘No one has ever taken it back …’

‘No, it doesn’t look like a Moony either.’

‘No European zoo has ever …’

‘What about Fluffykins?’ asked Sophie.

I shuddered.

‘If you must give it a name call it Bug-eyes,’ I said.

‘Oh, yes!’ said Jacquie, ‘that suits it.’

‘Good,’ I said, ‘I am relieved to know that we have successfully christened it. Now what about a cage for it?’

‘Oh, we’ve got one here,’ said Jacquie. ‘Don’t worry about that.’

We eased the animal into the cage, and it squatted on the floor glaring at us with unabated horror.

‘Isn’t it sweet?’ Jacquie repeated.

‘Is ’o a poppet?’ gurgled Sophie.

I sighed. It seemed that, in spite of all my careful training, both my wife and my secretary relapsed into the most revolting fubsy attitude when faced with anything fluffy.

‘Well,’ I said resignedly, ‘supposing you feed ’oos poppet? This poppet’s going inside to get an itsy-bitsy slug of gin.’