On our return from Eshobi, Jacquie and I loaded up our lorry with the cages of animals we had obtained to date, and set out for Bafut, leaving Bob and Sophie in Mamfe for a little longer to try and obtain some more of the rain-forest animals.

The journey from Mamfe to the highlands was long and tedious, but never failed to fascinate me. To begin with, the road ran through the thick forest of the valley in which Mamfe lay. The lorry roared and bumped its way along the red road between gigantic trees, each festooned with creepers and lianas, through which flew small flocks of hornbills, honking wildly, or pairs of jade-green touracos with magenta wings flashing as they flew. On the dead trees by the side of the road the lizards, orange, blue and black, vied with the pigmy kingfishers over the spiders, locusts and other succulent titbits to be found amongst the purple and white convolvulus flowers. At the bottom of each tiny valley ran a small stream, spanned by a creaking wooden bridge, and as the lorry roared across, great clouds of butterflies rose from the damp earth at the sides of the water and swirled briefly round the bonnet. After a couple of hours the road started to climb, at first almost imperceptibly, in a series of great swinging loops through the forest, and here and there by the side of the road you could see the giant tree-ferns like green fountains spouting miraculously out of the low growth. As one climbed higher, the forest gave way to occasional patches of grassland, bleached white by the sun.

Then, gradually, as though we were shedding a thick green coat, the forest started to drop away and the grassland took its place. The gay lizards ran sun-drunk across the road, and flocks of minute finches burst from the undergrowth and drifted across in front of us, their crimson feathering making them look like showers of sparks from some gigantic bonfire. The lorry roared and shuddered, steam blowing up from the radiator, as it made the final violent effort and reached the top of the escarpment. Behind lay the Mamfe forest, in a million shades of green, and before us was the grassland, hundreds of miles of rolling mountains, lying in folds to the farthest dim horizons, gold and green, stroked by cloud shadows, remote and beautiful in the sun. The driver eased the lorry on to the top of the hill and brought it to a shuddering halt that made the red dust swirl up in a waterspout that enveloped us and our belongings. He smiled the wide, happy smile of a man who has accomplished something of importance.

‘Why we stop?’ I inquired.

‘I go piss,’ explained the driver frankly, as he disappeared into the long grass at the side of the road.

Jacquie and I uncoiled ourselves from the red-hot interior of the cab and walked round to the back of the lorry to see how our creatures were faring. Phillip, seated stiff and upright on a tarpaulin, turned to us a face bright red with dust. His trilby, which had been a very delicate pearl grey when we started, was also bright red. He sneezed violently into a green handkerchief, and surveyed me reproachfully.

‘Dust too much, sah,’ he roared at me, in case the fact had escaped my observation. As Jacquie and I were almost as dusty in the front of the lorry, I was not inclined to be sympathetic.

‘How are the animals?’ I asked.

‘’E well, sah. But dis bush-hog, sah, ’e get strong head too much.’

‘Why, what the matter with it?’

‘’E done tief dis ma pillow,’ said Phillip indignantly.

I peered into Ticky the black-footed mongoose’s cage. She had whiled away the tedium of the journey by pushing her paw through the bars and gradually dragging in with her the small pillow which was part of our cook’s bedding. She was sitting on the remains, looking very smug and pleased with herself, surrounded by snow-drifts of feathers.

‘Never mind,’ I said consolingly, ‘I’ll buy you a new one. But you go watch your other things, eh? Sometime she go tief them as well.’

‘Yes, sah, I go watch um,’ said Phillip, casting a black look at the feather-smothered Ticky.

So we drove on through the green, gold and white grassland, under a blue sky veined with fine wisps of wind-woven white cloud, like frail twists of sheep’s wool blowing across the sky. Everything in this landscape seemed to be the work of the wind. The great outcrops of grey rocks were carved and ribbed by it into fantastic shapes; the long grass was curved over into frozen waves by it; the small trees had been bent, carunculated and distorted by it. And the whole landscape throbbed and sang with the wind, hissing softly in the grass, making the small trees creak and whine, hooting and blaring round the towering cornices of rock.

So we drove on towards Bafut, and towards the end of the day the sky became pale gold. Then, as the sun sank behind the farthest rim of mountains, the world was enveloped in the cool green twilight, and in the dusk the lorry roared round the last bend and drew up at the hub of Bafut, the compound of the Fon. To the left lay the vast courtyard, and behind it the clusters of huts in which lived the Fon’s wives and children. Dominating them all was the great hut in which dwelt the spirit of his father, and a great many other lesser spirits, looming like a monstrous, time-blackened beehive against the jade night sky. To the right of the road, perched on top of a tall bank, was the Fon’s Rest House, like a two-storey Italian villa, stone-built and with a neatly tiled roof. Shoe-box shaped, both lower and upper storeys were surrounded by wide verandahs, festooned with bougainvillaea covered with pink and brick-red flowers.

Tiredly we climbed out of the lorry and supervised the unloading of the animals and their installation on the top-storey verandah. Then the rest of the equipment was offloaded and stored, and while we made vague attempts to wash some of the red dust off our bodies, Phillip seized the remains of his bedding, his box full of cooking utensils and food and marched off to the kitchen quarters in a stiff, brisk way, like a military patrol going to quell a small but irritating insurrection. By the time we had fed the animals he had reappeared with an astonishingly good meal and having eaten it we fell into bed and slept like the dead.

The next morning, in the cool dawn light, we went to pay our respects to our host, the Fon. We made our way across the great courtyard and plunged into the maze of tiny squares and alleyways formed by the huts of the Fon’s wives. Presently, we found ourselves in a small courtyard shaded by an immense guava tree, and there was the Fon’s own villa, small, neat, built of stone and tiled with a wide verandah running along one side. And there, at the top of the steps running up to the verandah, stood my friend the Fon of Bafut.

He stood there, tall and slender, wearing a plain white robe embroidered with blue. On his head was a small skull-cap in the same colours. His face was split by the joyous, mischievous grin I knew so well and he was holding out one enormous slender hand in greeting.

‘My friend, Iseeya,’ I called, hurrying up the stairs to him.

‘Welcome, welcome … you done come … welcome,’ he exclaimed, seizing my hand in his huge palm and draping a long arm round my shoulders and patting me affectionately.

‘You well, my friend?’ I asked, peering up into his face.

‘I well, I well,’ he said grinning.

It seemed to me an understatement: he looked positively blooming. He had been well into his seventies when I had last met him, eight years before, and he appeared to have weathered the intervening years better than I had. I introduced Jacquie, and was quietly amused by the contrast. The Fon, six foot three inches, and appearing taller because of his robes, towered beamingly over Jacquie’s five-foot-one-inch, and her hand was as lost as a child’s in the depths of his great dusky paw.

‘Come, we go for inside,’ he said, and clutching our hands led us into his villa.

The interior was as I remembered it, a cool, pleasant room with leopard skins on the floor, and wooden sofas, beautifully carved, piled high with cushions. We sat down, and one of the Fon’s wives came forward carrying a tray with glasses and drinks on it. The Fon splashed Scotch into three glasses with a liberal hand, and passed them round, beaming at us. I surveyed the four inches of neat spirit in the bottom of my glass and sighed. I could see that the Fon had not, in my absence, joined the Temperance movement, whatever else he had done.

‘Chirri-ho!’ said the Fon, and downed half the contents of his glass at a gulp. Jacquie and I sipped ours more sedately.

‘My friend,’ I said, ‘I happy too much I see you again.’

‘Wah! Happy?’ said the Fon. ‘I get happy for see you. When dey done tell me you come for Cameroon again I get happy too much.’

I sipped my drink cautiously.

‘Some man done tell me that you get angry for me because I done write dat book about dis happy time we done have together before. So I de fear for come back to Bafut,’ I said.

‘Which kind of man tell you dis ting?’ he inquired furiously.

‘Some European done tell me.’

‘Ah! European,’ said the Fon shrugging, as if surprised that I should believe anything told to me by a white person, ‘Na lies dis.’

‘Good,’ I said, greatly relieved. ‘If I think you get angry for me my heart no go be happy.’

‘No, no, I no get angry for you,’ said the Fon, splashing another large measure of Scotch into my glass before I could stop him. ‘Dis book you done write … I like um foine … you done make my name go for all de world … every kind of people ’e know my name … na foine ting dis.’

Once again I realized I had underestimated the Fon’s abilities. He had obviously realized that any publicity is better than none. ‘Look um,’ he went on, ‘plenty plenty people come here for Bafut, all different different people, dey all show me dis your book ’e get my name for inside … na foine ting dis.’

‘Yes, na fine thing,’ I agreed, rather shaken. I had had no idea that I had unwittingly turned the Fon into a sort of Literary Lion.

‘Dat time I done go for Nigeria,’ he said, pensively holding the bottle of Scotch up to the light. ‘Dat time I done go for Lagos to meet dat Queen woman, all dis European dere ’e get dis your book. Plenty plenty people dey ask me for write dis ma name for inside dis your book.’

I gazed at him open-mouthed; the idea of the Fon in Lagos sitting and autographing copies of my book rendered me speechless.

‘Did you like the Queen?’ asked Jacquie.

‘Wah! Like? I like um too much. Na foine woman dat. Na small small woman, same same for you. But ’e get power, time no dere. Wah! Dat woman get power plenty.’

‘Did you like Nigeria?’ I asked.

‘I no like,’ said the Fon firmly. ‘’E hot too much. Sun, sun, sun, I shweat, I shweat. But dis Queen woman she get plenty power … she walka walka she never shweat. Na foine woman dis.’

He chuckled reminiscently, and absent-mindedly poured us all out another drink.

‘I done give dis Queen,’ he went on, ‘dis teeth for elephant. You savvay um?’

‘Yes, I savvay um,’ I said, remembering the magnificent carved tusk the Cameroons had presented to Her Majesty.

‘I done give dis teeth for all dis people of Cameroon,’ he explained. ‘Dis Queen she sit for some chair an’ I go softly softly for give her dis teeth. She take um. Den all dis European dere dey say it no be good ting for show your arse for dis Queen woman, so all de people walka walka backwards. I walka walka backwards. Wah! Na step dere, eh! I de fear I de fall, but I walka walka softly and I never fall … but I de fear too much.’

He chuckled over the memory of himself backing down the steps in front of the Queen until his eyes filled with tears.

‘Nigeria no be good place,’ he said, ‘hot too much … I shweat.’

At the mention of sweat I saw his eyes fasten on the whisky bottle, so I rose hurriedly to my feet and said that we really ought to be going, as we had a lot of unpacking to do. The Fon walked out into the sunlit courtyard with us, and, holding our hands, peered earnestly down into our faces.

‘For evening time you go come back,’ he said. ‘We go drink, eh?’

‘Yes, for evening time we go come,’ I assured him.

He beamed down at Jacquie.

‘For evening time I go show you what kind of happy time we get for Bafut,’ he said.

‘Good,’ said Jacquie, smiling bravely.

The Fon waved his hands in elegant dismissal, and then turned and made his way back into his villa, while we trudged over to the Rest House.

‘I don’t think I could face any breakfast after that Scotch,’ said Jacquie.

‘But that wasn’t drinking,’ I protested. ‘That was just a sort of mild apéritif to start the day. You wait until tonight.’

‘Tonight I shan’t drink … I’ll leave it to you two,’ said Jacquie firmly. ‘I shall have one drink and that’s all.’

After breakfast, while we were attending to the animals, I happened to glance over the verandah rail and noticed on the road below a small group of men approaching the house. When they drew nearer I saw that each of them was carrying either a raffia basket or a calabash with the neck stuffed with green leaves. I could hardly believe that they were bringing animals as soon as this, for generally it takes anything up to a week for the news to get around and for the hunters to start bringing in the stuff. But as I watched them with bated breath they turned off the road and started to climb the long flight of steps up to the verandah, chattering and laughing among themselves. Then, when they reached the top step they fell silent, and carefully laid their offerings on the ground.

‘Iseeya, my friends,’ I said.

‘Morning, Masa,’ they chorused, grinning.

‘Na whatee all dis ting?’

‘Na beef, sah,’ they said.

‘But how you savvay dat I done come for Bafut for buy beef?’ I asked, greatly puzzled.

‘Eh, Masa, de Fon ’e done tell us,’ said one of the hunters.

‘Good lord, if the Fon’s been spreading the news before we arrived we’ll be inundated in next to no time,’ said Jacquie.

‘We’re pretty well inundated now,’ I said, surveying the group of containers at my feet, ‘and we haven’t even unpacked the cages yet. Oh well, I suppose we’ll manage. Let’s see what they’ve got.’ I bent down, picked up a raffia bag and held it aloft.

‘Which man bring dis?’ I asked.

‘Na me, sah.’

‘Na whatee dere for inside?’

‘Na squill-lill, sah.’

‘What,’ inquired Jacquie, as I started to unravel the strings on the bag, ‘is a squill-lill?’

‘I haven’t the faintest idea,’ I replied.

‘Well, hadn’t you better ask?’ suggested Jacquie practically. ‘For all you know it might be a cobra or something.’

‘Yes, that’s a point,’ I agreed, pausing.

I turned to the hunter who was watching me anxiously.

‘Na whatee dis beef squill-lill?’

‘Na small beef, sah.’

‘Na, bad beef? ’E go chop man?’

‘No, sah, at all. Dis one na squill-lill small, sah … na picken.’

Fortified with this knowledge I opened the bag and peered into its depths. At the bottom, squirming and twitching in a nest of grass, lay a tiny squirrel about three and a half inches long. It couldn’t have been more than a few days old, for it was still covered in the neat, shining plush-like fur of an infant, and it was still blind. I lifted it out carefully and it lay in my hand making faint squeaking noises like something out of a Christmas cracker, pink mouth open in an O like a choirboy’s, minute paws making paddling motions against my fingers. I waited patiently for the flood of anthropomorphism to die down from my wife.

‘Well,’ I said, ‘if you want it, keep it. But I warn you it will be hell to feed. The only reason I can see for trying is because it’s a baby black-eared, and they’re quite rare.’

‘Oh, it’ll be all right,’ said Jacquie optimistically. ‘It’s strong and that’s half the battle.’

I sighed. I remembered the innumerable baby squirrels I had struggled with in various parts of the world, and how each one had seemed more imbecile and more bent on self-destruction than the last. I turned to the hunter. ‘Dis beef, my friend. Na fine beef dis, I like um too much. But ’e be picken, eh? Sometime ’e go die-o, eh?’

‘Yes, sah,’ agreed the hunter gloomily.

‘So I go pay you two two shilling now, and I go give you book. You go come back for two week time, eh, and if dis picken ’e alive I go pay you five five shilling more, eh? You agree?’

‘Yes, sah, I agree,’ said the hunter, grinning delightedly.

I paid him the two shillings, and then wrote out a promissory note for the other five shillings, and watched him tuck it carefully into a fold of his sarong.

‘You no go lose um,’ I said. ‘If you go lose um I no go pay you.’

‘No, Masa, I no go lose um,’ he assured me, grinning.

‘You know, it’s the most beautiful colour,’ said Jacquie, peering at the squirrel in her cupped hands. On that point I agreed with her. The diminutive head was bright orange, with a neat black rim behind each ear, as though its mother had not washed it properly. The body was brindled green on the back and pale yellow on the tummy, while the ridiculous tail was darkish green above and flame orange below.

‘What shall I call it?’ asked Jacquie.

I glanced at the quivering scrap, still doing choral practice in her palm.

‘Call it what the hunter called it: Squill-lill Small,’ I suggested. So Squill-lill Small she became, later to be abbreviated to Small for convenience.

While engaged in this problem of nomenclature I had been busy untying another raffia basket, without having taken the precaution of asking the hunter what it contained. So, when I incautiously opened it, a small, pointed, rat-like face appeared, bit me sharply on the finger, uttered a piercing shriek of rage and disappeared into the depths of the basket again.

‘What on earth was that?’ asked Jacquie, as I sucked my finger and cursed, while all the hunters chorused ‘Sorry, sah, sorry, sah,’ as though they had been collectively responsible for my stupidity.

‘That fiendish little darling is a pigmy mongoose,’ I said. ‘For their size they’re probably the fiercest creatures in Bafut, and they’ve got the most penetrating scream of any small animal I know, except a marmoset.’

‘What are we going to keep it in?’

‘We’ll have to unpack some cages. I’ll leave it in the bag until I’ve dealt with the rest of the stuff,’ I said, carefully tying the bag up again.

‘It’s nice to have two different species of mongoose,’ said Jacquie.

‘Yes,’ I agreed, sucking my finger. ‘Delightful.’

The rest of the containers, when examined, yielded nothing more exciting than three common toads, a small green viper and four weaver-birds which I did not want. So, having disposed of them and the hunters, I turned my attention to the task of housing the pigmy mongoose. One of the worst things you can do on a collecting trip is to be unprepared with your caging. I had made this mistake on my first expedition; although we had taken a lot of various equipment, I had failed to include any ready-made cages, thinking there would be plenty of time to build them on the spot. The result was that the first flood of animals caught us unprepared and by the time we had struggled night and day to house them all adequately, the second wave of creatures had arrived and we were back where we started. At one point I had as many as six different creatures tied to my camp-bed on strings. After this experience I have always taken the precaution of bringing some collapsible cages with me on a trip so that, whatever else happens, I am certain I can accommodate at least the first forty or fifty specimens.

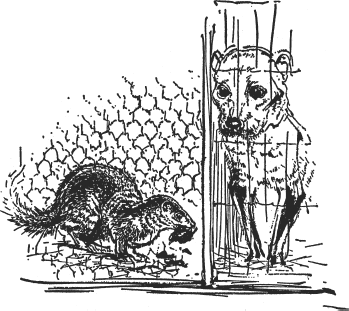

I now erected one of our specially built cages, filled it with dry banana leaves and eased the pigmy mongoose into it without getting bitten. It stood in the centre of the cage, regarding me with small, bright eyes, one dainty paw held up, and proceeded to utter shriek upon shriek of fury until our ears throbbed. The noise was so penetrating and painful that, in desperation, I threw a large lump of meat into the cage. The pigmy leaped on it, shook it vigorously to make sure it was dead and then carried it off to a corner where it settled down to eat. Though it still continued to shriek at us, the sounds were now mercifully muffled by the food. I placed the cage next to the one occupied by Ticky, the black-footed mongoose, and sat down to watch.

At a casual glance no one would think that the two animals were even remotely related. The black-footed mongoose, although still only a baby, measured two feet in length and stood about eight inches in height. She had a blunt, rather dog-like face with dark, round and somewhat protuberant eyes. Her body, head and tail were a rich creamy-white, while her slender legs were a rich brown that was almost black. She was sleek, sinuous and svelte and reminded me of a soft-skinned Parisienne belleamie clad in nothing more than two pairs of black silk stockings. In contrast the pigmy mongoose looked anything but Parisienne. It measured, including tail, about ten inches in length. It had a tiny, sharply pointed face with a small, circular pink nose and a pair of small, glittering, sherry-coloured eyes. The fur, which was rather long and thick, was a deep chocolate brown with a faint ginger tinge here and there.

Ticky, who was very much the grande dame, peered out of her cage at the newcomer with something akin to horror on her face, watching it fascinated as it shrieked and grumbled over its gory hunk of meat. Ticky was herself a very dainty and fastidious feeder and would never have dreamt of behaving in this uncouth way, yelling and screaming with your mouth full and generally carrying on as though you had never had a square meal in your life. She watched the pigmy for a moment or so and then gave a sniff of scorn, turned round elegantly two or three times and then lay down and went to sleep. The pigmy, undeterred by this comment on its behaviour, continued to champ and shrill over the last bloody remnants of its food. When the last morsel had been gulped down, and the ground around carefully inspected for any bits that might have been overlooked, it sat down and scratched itself vigorously for a while and then curled up and went to sleep as well. When we woke it up about an hour later to record its voice for posterity, it produced such screams of rage and indignation that we were forced to move the microphone to the other end of the verandah. But by the time evening came we had not only successfully recorded the pigmy mongoose but Ticky as well, and had unpacked ninety per cent of our equipment into the bargain. So we bathed, changed and dined feeling well satisfied with ourselves.

After dinner we armed ourselves with a bottle of whisky and an abundant supply of cigarettes and, taking our pressure lamp, we set off for the Fon’s house. The air was warm and drowsy, full of the scents of wood smoke and sun-baked earth. Crickets tinkled and trilled in the grass verges of the road and in the gloomy fruit-trees around the Fon’s great courtyard we could hear the fruit bats honking and flapping their wings among the branches. In the courtyard a group of the Fon’s children were standing in a circle clapping their hands and chanting in some sort of game, and away through the trees in the distance a small drum throbbed like an irregular heart beat. We made our way through the maze of wives’ huts, each lit by the red glow of a cooking fire, each heavy with the smell of roasting yams, frying plantain, stewing meat or the sharp, pungent reek of dried salt fish. We came presently to the Fon’s villa and he was waiting on the steps to greet us, looming large in the gloom, his robe swishing as he shook our hands.

‘Welcome, welcome,’ he said, beaming, ‘come, we go for inside.’

‘I done bring some whisky for make our heart happy,’ I said, flourishing the bottle as we entered the house.

‘Wah! Good, good,’ said the Fon, chuckling. ‘Dis whisky na foine ting for make man happy.’

He was wearing a wonderful scarlet and yellow robe that glowed like a tiger skin in the soft lamplight, and one slender wrist carried a thick, beautifully carved ivory bracelet. We sat down and waited in silence while the solemn ritual of the pouring of the first drink was observed. Then, when each of us was clutching half a tumblerful of neat whisky, the Fon turned to us, giving his wide, mischievous grin.

‘Chirri-ho!’ he said, raising his glass, ‘tonight we go have happy time.’ And so began what we were to refer to later as The Evening of the Hangover.

As the level in the whisky bottle fell the Fon told us once again about his trip to Nigeria, how hot it had been and how much he had ‘shweated’. His praise for the Queen knew no bounds, for, as he pointed out, here was he in his own country feeling the heat and yet the Queen could do twice the amount of work and still manage to look cool and charming. I found his lavish and perfectly genuine praise rather extraordinary, for the Fon belonged to a society where women are considered to be nothing more than rather useful beasts of burden.

‘You like musica?’ inquired the Fon of Jacquie, when the subject of the Nigerian tour was exhausted.

‘Yes,’ said Jacquie, ‘I like it very much.’

‘You remember dis my musica?’ he asked me.

‘Yes, I remember. You get musica time no dere, my friend.’

The Fon gave a prolonged crow of amusement.

‘You done write about dis my musica inside dis your book, eh?’

‘Yes, that’s right.’

‘And,’ said the Fon, coming to the point, ‘you done write about dis dancing an’ dis happy time we done have, eh?’

‘Yes … all dis dance we done do na fine one.’

‘You like we go show dis your wife what kind of dance we get here for Bafut?’ he inquired, pointing a long forefinger at me.

‘Yes, I like too much.’

‘Foine, foine … come, we go for dancing house,’ he said, rising to his feet majestically, and stifling a belch with one slender hand. Two of his wives, who had been sitting quietly in the background, rushed forward and seized the tray of drinks and scuttled ahead of us, as the Fon led us out of his house and across the compound towards his dancing house.

The dancing house was a great, square building, not unlike the average village hall, but with an earth floor and very few and very small windows. At one end of the building stood a line of wickerwork arm-chairs, which constituted a sort of Royal enclosure, and on the wall above these were framed photographs of various members of the Royal family. As we entered the dancing hall the assembled wives, about forty or fifty of them, uttered the usual greeting, a strange, shrill ululation, caused by yelling loudly and clapping their hands rapidly over their mouths at the same time. The noise was deafening. All the petty councillors there in their brilliant robes clapped their hands as well, and thus added to the general racket. Nearly deafened by this greeting, Jacquie and I were installed in two chairs, one on each side of the Fon, the table of drinks was placed in front of us, and the Fon, leaning back in his chair, surveyed us both with a wide and happy grin.

‘Now we go have happy time,’ he said, and leaning forward poured out half a tumblerful of Scotch each from the depths of a virgin bottle that had just been broached.

‘Chirri-ho,’ said the Fon.

‘Chin-chin,’ I said absent-mindedly.

‘Na whatee dat?’ inquired the Fon with interest.

‘What?’ I asked, puzzled.

‘Dis ting you say.’

‘Oh, you mean chin-chin?’

‘Yes, yes, dis one.’

‘It’s something you say when you drink.’

‘Na same same for Chirri-ho?’ asked the Fon, intrigued.

‘Yes, na same same.’

He sat silent for a moment, his lips moving, obviously comparing the respective merits of the two toasts. Then he raised his glass again.

‘Shin-shin,’ said the Fon.

‘Chirri-ho!’ I responded, and the Fon lay back in his chair and went off into a paroxysm of mirth.

By now the band had arrived. It was composed of four youths and two of the Fon’s wives and the instruments consisted of three drums, two flutes and a calabash filled with dried maize that gave off a pleasant rustling noise similar to a marimba. They got themselves organized in the corner of the dancing house, and then gave a few experimental rolls on the drums, watching the Fon expectantly. The Fon, having recovered from the joke, barked out an imperious order and two of his wives placed a small table in the centre of the dance floor and put a pressure lamp on it. The drums gave another expectant roll.

‘My friend,’ said the Fon, ‘you remember when you done come for Bafut before you done teach me European dance, eh?’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I remember.’

This referred to one of the Fon’s parties when, having partaken liberally of the Fon’s hospitality, I had proceeded to show him, his councillors and wives how to do the conga. It had been a riotous success, but in the eight years that had passed I had supposed that the Fon would have forgotten about it.

‘I go show you,’ said the Fon, his eyes gleaming. He barked out another order and about twenty of his wives shuffled out on to the dance floor and formed a circle round the table, each one holding firmly to the waist of the one in front. Then they assumed a strange, crouching position, rather like runners at the start of a race, and waited.

‘What are they going to do?’ whispered Jacquie.

I watched them with an unholy glee. ‘I do believe,’ I said dreamily, ‘That he’s been making them dance the conga ever since I left, and we’re now going to have a demonstration.’

The Fon lifted a large hand and the band launched itself with enthusiasm into a Bafut tune that had the unmistakable conga rhythm. The Fon’s wives, still in their strange crouching position, proceeded to circle round the lamp, kicking their black legs out on the sixth beat, their brows furrowed in concentration. The effect was delightful.

‘My friend,’ I said, touched by the demonstration, ‘dis na fine ting you do.’

‘Wonderful,’ agreed Jacquie enthusiastically, ‘they dance very fine.’

‘Dis na de dance you done teach me,’ explained the Fon.

‘Yes, I remember.’

He turned to Jacquie, chuckling. ‘Dis man your husband ’e get plenty power … we dance, we dance, we drink … Wah! We done have happy time.’

The band came to an uneven halt, and the Fon’s wives, smiling shyly at our applause, rose from their crouching position and returned to their former places along the wall. The Fon barked an order and a large calabash of palm wine was brought in and distributed among the dancers, each getting their share poured into their cupped hands. Stimulated by this sight the Fon filled all our glasses again.

‘Yes,’ he went on, reminiscently, ‘dis man your husband get plenty power for dance and drink.’

‘I no get power now,’ I said, ‘I be old man now.’

‘No, no, my friend,’ said the Fon laughing, ‘I be old, you be young.’

‘You look more young now den for the other time I done come to Bafut,’ I said, and really meant it.

‘That’s because you’ve got plenty wives,’ said Jacquie.

‘Wah! No!’ said the Fon, shocked. ‘Dis ma wives tire me too much.’

He glared moodily at the array of females standing along the wall, and sipped his drink. ‘Dis ma wife dey humbug me too much,’ he went on.

‘My husband says I humbug him,’ said Jacquie.

‘Your husband catch lucky. ’E only get one wife, I get plenty,’ said the Fon, ‘an’ dey de humbug me time no dere.’

‘But wives are very useful,’ said Jacquie.

The Fon regarded her sceptically.

‘If you don’t have wives you can’t have babies … men can’t have babies,’ said Jacquie practically.

The Fon was so overcome with mirth at this remark I thought he might have a stroke. He lay back in his chair and laughed until he cried. Presently he sat up, wiping his eyes, still shaking with gusts of laughter. ‘Dis woman your wife get brain,’ he said, still chuckling, and poured Jacquie out an extra large Scotch to celebrate her intelligence. ‘You be good wife for me,’ he said, patting her on the head affectionately. ‘Shin-shin.’

The band now returned, wiping their mouths from some mysterious errand outside the dancing house and, apparently well fortified, launched themselves into one of my favourite Bafut tunes, the Butterfly dance. This was a pleasant, lilting little tune and the Fon’s wives again took the floor and did the delightful dance that accompanied it. They danced in a row with minute but complicated hand and feet movements, and then the two that formed the head of the line joined hands, while the one at the farther end of the line whirled up and then fell backwards, to be caught and thrown upright again by the two with linked hands. As the dance progressed and the music got faster and faster the one representing the butterfly whirled more and more rapidly, and the ones with linked hands catapulted her upright again with more and more enthusiasm. Then, when the dance reached its feverish climax, the Fon rose majestically to his feet, amid screams of delight from the audience, and joined the end of the row of dancing wives. He started to whirl down the line, his scarlet and yellow robe turning into a blur of colour, loudly singing the words of the song.

‘I dance, I dance, and no one can stop me,’ he carolled merrily, ‘but I must take care not to fall to the ground like the butterfly.’

He went whirling down the line of wives like a top, his voice booming out above theirs.

‘I hope to God they don’t drop him,’ I said to Jacquie, eyeing the two short, fat wives who, with linked hands, were waiting rather nervously at the head of the line to receive their lord and master.

The Fon performed one last mighty gyration and hurled himself backwards at his wives, who caught him neatly enough but reeled under the shock. As the Fon landed he spread his arms wide so that for a moment his wives were invisible under the flowing sleeves of his robes and he lay there looking very like a gigantic, multicoloured butterfly. He beamed at us, lolling across his wives’ arms, his skull-cap slightly askew, and then his wives with an effort bounced him back to his feet again. Grinning and panting he made his way back to us and hurled himself into his chair.

‘My friend, na fine dance dis,’ I said in admiration. ‘You get power time no dere.’

‘Yes,’ agreed Jacquie, who had also been impressed by this display, ‘you get plenty power.’

‘Na good dance dis, na foine one,’ said the Fon, chuckling, and automatically pouring us all out another drink.

‘You get another dance here for Bafut I like too much,’ I said. ‘Dis one where you dance with dat beer-beer for horse.’

‘Ah, yes, yes, I savvay um,’ said the Fon. ‘Dat one where we go dance with dis tail for horshe.’

‘That’s right. Sometime, my friend, you go show dis dance for my wife?’

‘Yes, yes, my friend,’ he said. He leant forward and gave an order and a wife scuttled out of the dancing hall. The Fon turned and smiled at Jacquie.

‘Small time dey go bring dis tail for horshe an’ den we go dance,’ he said.

Presently the wife returned carrying a large bundle of white, silky horses’ tails, each about two feet long, fitted into handles beautifully woven out of leather thongs. The Fon’s tail was a particularly long and luxuriant one, and the thongs that had been used to make the handle were dyed blue, red and gold. The Fon swished it experimentally through the air with languid, graceful movements of his wrist, and the hair rippled and floated like a cloud of smoke before him. Twenty of the Fon’s wives, each armed with a switch, took the floor and formed a circle. The Fon walked over and stood in the centre of the circle; he gave a wave of his horse’s tail, the band struck up and the dance was on.

Of all the Bafut dances this horsetail dance was undoubtedly the most sensuous and beautiful. The rhythm was peculiar, the small drums keeping up a sharp, staccato beat, while beneath them the big drums rumbled and muttered and the bamboo flutes squeaked and twittered with a tune that seemed to have nothing to do with the drums and yet merged with it perfectly. To this tune the Fon’s wives gyrated slowly round in a clockwise direction, their feet performing minute but formalized steps, while they waved the horses’ tails gently to and fro across their faces. The Fon, meanwhile, danced round the inside of the circle in an anti-clockwise direction, bobbing, stamping and twisting in a curiously stiff, unjointed sort of way, while his hand with incredibly supple wrist movements kept his horse’s tail waving through the air in a series of lovely and complicated movements. The effect was odd and almost indescribable: one minute the dancers resembled a bed of white seaweed, moved and rippled by sea movement, and the next minute the Fon would stamp and twist, stiff-legged, like some strange bird with white plumes, absorbed in a ritual dance of courtship among his circle of hens. Watching this slow pavane and the graceful movements of the tails had a curious hypnotic effect, so that even when the dance ended with a roll of drums one could still see the white tails weaving and merging before your eyes.

The Fon moved gracefully across the floor towards us, twirling his horse’s tail negligently, and sank into his seat. He beamed breathlessly at Jacquie.

‘You like dis ma dance?’ he asked.

‘It was beautiful,’ she said. ‘I liked it very much.’

‘Good, good,’ said the Fon, well pleased. He leaned forward and inspected the whisky bottle hopefully, but it was obviously empty. Tactfully I refrained from mentioning that I had some more over at the Rest House. The Fon surveyed the bottle gloomily.

‘Whisky done finish,’ he pointed out.

‘Yes,’ I said unhelpfully.

‘Well,’ said the Fon, undaunted, ‘we go drink gin.’

My heart sank, for I had hoped that we could now move on to something innocuous like beer to quell the effects of so much neat alcohol. The Fon roared at one of his wives and she ran off and soon reappeared with a bottle of gin and one of bitters. The Fon’s idea of gin-drinking was to pour out half a tumblerful and then colour it a deep brown with bitters. The result was guaranteed to slay an elephant at twenty paces. Jacquie, on seeing this cocktail the Fon concocted for me, hastily begged to be excused, saying that she couldn’t drink gin on doctor’s orders. The Fon, though obviously having the lowest possible opinion of a medical man who could even suggest such a thing, accepted with good grace.

The band started up again and everyone poured on to the floor and started to dance, singly and in couples. As the rhythm of the tune allowed it, Jacquie and I got up and did a swift foxtrot round the floor, the Fon roaring encouragement and his wives hooting with pleasure.

‘Foine, foine,’ shouted the Fon as we swept past.

‘Thank you, my friend,’ I shouted back, steering Jacquie carefully through what looked like a flower-bed of councillors in their multicoloured robes.

‘I do wish you wouldn’t tread on my feet,’ said Jacquie plaintively.

‘Sorry. My compass bearings are never at their best at this hour of night.’

‘So I notice,’ said Jacquie acidly.

‘Why don’t you dance with the Fon?’ I inquired.

‘I did think of it, but I wasn’t sure whether it was the right thing for a mere woman to ask him.’

‘I think he’d be tickled pink. Ask him for the next dance,’ I suggested.

‘What can we dance?’ asked Jacquie.

‘Teach him something he can add to his Latin American repertoire,’ I said, ‘How about a rumba?’

‘I think a samba would be easier to learn at this hour of night,’ said Jacquie. So, when the dance ended we made our way back to where the Fon was sitting, topping up my glass.

‘My friend,’ I said, ‘you remember dis European dance I done teach you when I done come for Bafut before?’

‘Yes, yes, na foine one,’ he replied, beaming.

‘Well, my wife like to dance with you and teach you other European dance. You agree?’

‘Wah!’ bellowed the Fon in delight, ‘foine, foine. Dis your wife go teach me. Foine, foine, I agree.’

Eventually we discovered a tune that the band could play that had a vague samba rhythm and Jacquie and the Fon rose to their feet, watched breathlessly by everyone in the room.

The contrast between the Fon’s six-foot-three and Jacquie’s five-foot-one made me choke over my drink as they took the floor. Very rapidly Jacquie showed him the simple, basic steps of the samba, and to my surprise the Fon mastered them without trouble. Then he seized Jacquie in his arms and they were off. The delightful thing from my point of view was that as he clasped Jacquie tightly to his bosom she was almost completely hidden by his flowing robes; indeed, at some points in the dance you could not see her at all and it looked as though the Fon, having mysteriously grown another pair of feet, was dancing round by himself. There was something else about the dance that struck me as curious, but I could not pin it down for some time. Then I suddenly realized that Jacquie was leading the Fon. They danced past, both grinning at me, obviously hugely enjoying themselves.

‘You dance fine, my friend,’ I shouted. ‘My wife done teach you fine.’

‘Yes, yes,’ roared the Fon over the top of Jacquie’s head. ‘No foine dance dis. Your wife na good wife for me.’

Eventually, after half an hour’s dancing, they returned to their chairs, hot and exhausted. The Fon took a large gulp of neat gin to restore himself, and then leaned across to me.

‘Dis your wife na foine,’ he said in a hoarse whisper, presumably thinking that praise might turn Jacquie’s head. ‘She dance foine. She done teach me foine. I go give her mimbo … special mimbo I go give her.’

I turned to Jacquie who, unaware of her fate, was sitting fanning herself.

‘You’ve certainly made a hit with our host,’ I said.

‘He’s a dear old boy,’ said Jacquie, ‘and he dances awfully well … did you see how he picked up that samba in next to no time?’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘and he was so delighted with your teaching that he’s going to reward you.’

Jacquie looked at me suspiciously. ‘How’s he going to reward me?’ she asked.

‘You’re now going to receive a calabash of special mimbo … palm wine.’

‘Oh God, and I can’t stand the stuff,’ said Jacquie in horror.

‘Never mind. Take a glassful, taste it, tell him it’s the finest you’ve ever had, and then ask if he will allow you to share it with his wives.’

Five calabashes were brought, the neck of each plugged with green leaves, and the Fon solemnly tasted them all before making up his mind which was the best vintage. Then a glass was filled and passed to Jacquie. Summoning up all her social graces she took a mouthful, rolled it round her mouth, swallowed and allowed a look of intense satisfaction to appear on her face.

‘This is very fine mimbo,’ she proclaimed in delighted astonishment, with the air of one who has just been presented with a glass of Napoleon brandy. The Fon beamed. Jacquie took another sip, as he watched her closely. An even more delighted expression appeared on her face.

‘This is the best mimbo I’ve ever tasted,’ said Jacquie.

‘Ha! Good!’ said the Fon, with pleasure. ‘Dis na foine mimbo. Na fresh one.’

‘Will you let your wives drink with me?’ asked Jacquie.

‘Yes, yes,’ said the Fon with a lordly wave of his hand, and so the wives shuffled forward, grinning shyly, and Jacquie hastily poured the remains of the mimbo into their pink palms.

At this point, the level of the gin bottle having fallen alarmingly, I suddenly glanced at my watch and saw, with horror, that in two and a half hours it would be dawn. So, pleading heavy work on the morrow, I broke up the party. The Fon insisted on accompanying us to the foot of the steps that led up to the Rest House, preceded by the band. Here he embraced us fondly.

‘Good night, my friend,’ he said, shaking my hand.

‘Good night,’ I replied. ‘Thank you. You done give us happy time.’

‘Yes,’ said Jacquie, ‘thank you very much.’

‘Wah!’ said the Fon, patting her on the head, ‘we done dance foine. You be good wife for me, eh?’

We watched him as he wended his way across the great courtyard, tall and graceful in his robes, the boy trotting beside him carrying the lamp that cast a pool of golden light about him. They disappeared into the tangle of huts, and the twittering of the flutes and the bang of the drums became fainter and died away, until all we could hear was the calls of crickets and tree-frogs and the faint honking cries of the fruit bats. Somewhere in the distance the first cock crowed, huskily and sleepily, as we crept under our mosquito nets.