There are several different ways of making an animal film, and probably one of the best methods is to employ a team of cameramen who spend about two years in some tropical part of the world filming the animals in their natural state. Unfortunately this method is expensive, and unless you have the time and the resources of Hollywood behind you it is out of the question.

For someone like myself, with only a limited amount of time and money to spend in a country, the only way to film animals is under controlled conditions. The difficulties of trying to film wild animals in a tropical forest are enough to make even the most ardent photographer grow pale. To begin with you hardly ever see a wild animal and, when you do, it is generally only a momentary glimpse as it scuttles off into the undergrowth. To be in the right spot at the right time with your camera set up, your exposure correct and an animal in front of you in a suitable setting, engaged in some interesting and filmable action, would be almost a miracle. So, the only way round this is to catch your animal first and establish it in captivity. Once it has lost some of its fear of human beings you can begin work. Inside a huge netting ‘room’ you create a scene which is as much like the animal’s natural habitat as possible, and yet which is – photographically speaking – suitable. That is to say, it must not have too many holes in which a shy creature can hide, your undergrowth must not be so thick that you get awkward patches of shade, and so on. Then you introduce your animal to the set, and allow it time to settle down, which may be anything from an hour to a couple of days.

It is essential, of course, to have a good knowledge of the animal’s habits, and to know how it will react under certain circumstances. For example, a hungry pouched rat, if released in an appropriate setting and finding a lavish selection of forest fruits on the ground, will promptly proceed to stuff as many of them into his immense cheek pouches as they will hold, so that in the end he looks as though he is suffering from a particularly virulent attack of mumps. If you don’t want to end up with nothing more exciting than a series of pictures of some creature wandering aimlessly to and fro amid bushes and grass, you must provide the circumstances which will allow it to display some interesting habit or action. However, even when you have reached this stage you still require two other things: patience and luck. An animal – even a tame one – cannot be told what to do like a human actor. Sometimes a creature which has performed a certain action day after day for weeks will, when faced with a camera, develop an acute attack of stage fright, and refuse to perform. When you have spent hours in the hot sun getting everything ready, to be treated to this sort of display of temperament makes you feel positively homicidal.

A prize example of the difficulties of animal photography was, I think, the day we attempted to photograph the water chevrotain. These delightful little antelopes are about the size of a fox-terrier, with a rich chestnut coat handsomely marked with streaks and spots of white. Small and dainty, the water chevrotain is extremely photogenic. There are several interesting points about the chevrotain, one of which is its adaptation to a semi-aquatic life in the wild state. It spends most of its time wading and swimming in streams in the forest and can even swim for considerable distances under water. The second curious thing is that it has a passion for snails and beetles, and such carnivorous habits in an antelope are most unusual. The third notable characteristic is its extraordinary placidity and tameness: I have known a chevrotain, an hour after capture, take food from my hand and allow me to tickle its ears, for all the world as if it had been born in captivity.

Our water chevrotain was no exception; she was ridiculously tame, adored having her head and tummy scratched and would engulf, with every sign of satisfaction, any quantity of snails and beetles you cared to provide. Apart from this she spent her spare time trying to bathe in her water bowl, into which she could just jam – with considerable effort – the extreme rear end of her body.

So, to display her carnivorous and aquatic habits, I designed a set embracing a section of river bank. The undergrowth was carefully placed so that it would show off her perfect adaptive coloration to the best advantage. One morning, when the sky was free from cloud and the sun was in the right place, we carried the chevrotain cage out to the set and prepared to release her.

‘The only thing I’m afraid of,’ I said to Jacquie, ‘is that I’m not going to get sufficient movement out of her. You know how quiet she is … she’ll probably walk into the middle of the set and refuse to move.’

‘Well, if we offer her a snail or something from the other side I should think she’ll walk across,’ said Jacquie.

‘As long as she doesn’t just stand there, like a cow in a field. I want to get some movement out of her,’ I said.

I got considerably more movement out of her than I anticipated. The moment the slide of her cage was lifted she stepped out daintily and paused with one slender hoof raised. I started the camera and awaited her next move. Her next move was somewhat unexpected. She shot across my carefully prepared set like a rocket, went right through the netting wall as if it had not been there and disappeared into the undergrowth in the middle distance before any of us could make a move to stop her. Our reactions were slow, because this was the last thing we had expected, but as I saw my precious chevrotain disappearing from view I uttered such a wail of anguish that everyone, including Phillip the cook, dropped whatever they were doing and assembled on the scene like magic.

‘Water beef done run,’ I yelled. ‘I go give ten shillings to the man who go catch um.’

The effect of this lavish offer was immediate. A wedge of Africans descended on to the patch of undergrowth into which the antelope had disappeared, like a swarm of hungry locusts. Within five minutes Phillip, uttering a roar of triumph like a sergeant-major, emerged from the bushes clutching to his bosom the kicking, struggling antelope. When we replaced her in her cage she stood quite quietly, gazing at us with limpid eyes as if astonished at all the fuss. She licked my hand in a friendly fashion, and when tickled behind the ears went off into her usual trance-like state, with half-closed eyes. We spent the rest of the day trying to film the wretched creature. She behaved beautifully in her box, splashing in a bowl of water to show how aquatic she was, eating beetles and snails to show how carnivorous she was, but the moment she was released into the film set she fled towards the horizon as if she had a brace of leopards on her tail. At the end of the day, hot and exhausted, I had exposed fifty feet of film, all of which showed her standing stock still outside her box, preparatory to dashing away. Sadly we carried her cage back to the Rest House, while she lay placidly on her banana-leaf bed and munched beetles. It was the last time we tried to photograph the water chevrotain.

Another creature that caused me untold anguish in the photographic field was a young Woodford’s owl called, with singular lack of originality, Woody. Woodfords are very lovely owls, with a rich chocolate plumage splashed and blotched with white, and possessing what must be the most beautiful eyes in the whole of the owl family. They are large, dark and liquid, with heavy lids of a delicate pinky-mauve. These they raise and lower over their eyes in what seems to be slow motion, like an ancient film actress considering whether to make a comeback. This seductive fluttering of eyelids is accompanied by loud clickings of the beak-like castanets. When excited the eyelid fluttering becomes very pronounced and the birds sway from side to side on the perch, as if about to start a hula-hula, and then they suddenly spread their wings and stand there clicking their beaks at you, looking like a tombstone angel of the more fiercely religious variety. Woody would perform all these actions perfectly inside his cage and would, moreover, perform them to order when shown a succulent titbit like a small mouse. I felt sure that, if he was provided with a suitable background, I could get his display on film with the minimum of trouble.

So, in the netting room I used for bird photography I set to and created what looked like a forest tree, heavily overgrown with creepers and other parasites, using green leaves and a blue sky as background. Then I carried Woody out and placed him on the branch in the midst of this wealth of foliage. The action I wanted him to perform was a simple and natural one not calculated to tax even the brain of an owl. With a little co-operation on his part the whole thing could have been over in ten minutes. He sat on the branch regarding us with wide-eyed horror, while I took up my position behind the camera. Just as I pressed the button he blinked his eyes once, very rapidly, and then, as if overcome with disgust at our appearance, he very firmly turned his back on us. Trying to remember that patience was the first requisite of an animal photographer, I wiped the sweat from my eyes, walked up to the branch, turned him round and walked back to the camera. By the time I had reached it Woody once more had his back towards us. I thought that maybe the light was too strong, so several members of the staff were sent to cut branches and these were rigged up so that the bird was sheltered from the direct rays of the sun. But still he persisted in keeping his back to us. It was obvious that, if I wanted to photograph him. I would have to rearrange my set so that it faced the opposite way. After considerable labour about a ton of undergrowth was carefully shifted and rearranged so that Woody was now facing the way he obviously preferred.

During this labour, while we sweated with massive branches and coils of creepers, he sat there regarding us in surprise. He generously allowed me to get the camera set up in the right position (a complicated job, for I was now shooting almost directly into the sun) and then he calmly turned his back on it. I could have strangled him. By this time ominous black clouds were rolling up, preparatory to obscuring the sun, and so further attempts at photography were impossible. I packed up the camera and then walked to the branch, murder in my heart, to collect my star. As I approached he turned round, clicked his beak delightedly, executed a rapid hula-hula and then spread his wings and bowed to me, with the mock-shy air of an actor taking his seventeenth curtain call.

Of course not all our stars caused us trouble. In fact, one of the best sequences I managed to get on film was accomplished with the minimum of fuss and in record time. And yet, on the face of it, one would have thought that it was a much more difficult object to achieve than getting an owl to spread his wings. Simply, I wanted to get some shots of an egg-eating snake robbing a nest. Egg-eating snakes measure about two feet in length and are very slender. Coloured a pinkish-brown, mottled with darker markings, they have strange, protuberant eyes of a pale silvery colour with fine vertical pupils like a cat’s. The curious point about them is that three inches from the throat (internally, of course) the vertebrae protrude, hanging down like stalactites. The reptile engulfs an egg, whole, and this passes down its body until it lies directly under these vertebrae. Then the snake contracts its muscles and the spikes penetrate the egg and break it; the yolk and white are absorbed and the broken shell, now a flattened pellet, is regurgitated. The whole process is quite extraordinary and had never, as far as I knew, been recorded on film.

We had, at that time, six egg-eating snakes, all of which were, to my delight, identical in size and coloration. The local children did a brisk trade in bringing us weaver-birds’ eggs to feed this troupe of reptiles, for they seemed capable of eating any number we cared to put in their cage. In fact, the mere introduction of an egg into the cage changed them from a somnolent pile of snakes to a writhing bundle, each endeavouring to get at the egg first. But, although they behaved so beautifully in the cage, after my experiences with Woody and the water chevrotain, I was inclined to be a bit pessimistic. However, I created a suitable set (a flowering bush in the branches of which was placed a small nest) and collected a dozen small blue eggs as props. Then the snakes were kept without their normal quota of eggs for three days, to make sure they all had good appetites. This, incidentally, did not hurt them at all, for all snakes can endure considerable fasts, which with some of the bigger constrictors run into months or years. However, when my stars had got what I hoped was a good edge to their appetites, we started work.

The snakes’ cage was carried out to the film set, five lovely blue eggs were placed in the nest and then one of the reptiles was placed gently in the branches of the bush, just above the nest. I started the camera and waited.

The snake lay flaccidly across the branches seeming a little dazed by the sunlight after the cool dimness of its box. In a moment its tongue started to flicker in and out, and it turned its head from side to side in an interested manner. Then with smooth fluidity it started to trickle through the branches towards the nest. Slowly it drew closer and closer, and when it reached the rim of the nest, it peered over the edge and down at the eggs with its fierce silvery eyes. Its tongue flicked again as if it were smelling the eggs and it nosed them gently like a dog with a pile of biscuits. Then it pulled itself a little farther into the nest, turned its head sideways, opened its mouth wide and started to engulf one of the eggs. All snakes have a jaw so constructed that they can dislocate the hinge, which enables them to swallow a prey that, at first sight, looks too big to pass through their mouths. The egg-eater was no exception and he neatly dislocated his jaws and the skin of his throat stretched until each scale stood out individually and you could see the blue of the egg shining through the fine, taut skin as the egg was forced slowly down his throat. When the egg was about an inch down his body he paused for a moment’s meditation and then swung himself out of the nest and into the branches. Here, as he made his way along, he rubbed the great swelling in his body that the egg had created against the branches so that the egg was forced farther and farther down.

Elated with this success we returned the snake to his box so that he could digest his meal in comfort, and I shifted the camera’s position and put on my big lenses for close-up work. We put another egg into the nest to replace the one taken, and then got out another egg-eater. This was the beauty of having all the snakes of the same size and coloration: as the first snake would not look at another egg until he had digested the first, he could not be used in the close-up shots. But the new one was identical and as hungry as a hunter, and so without any trouble whatsoever I got all the close-up shots I needed as he glided rapidly down to the nest and took an egg. I did the whole thing all over again with two other snakes and on the finished film these four separate sequences were intercut and no one, seeing the finished product, could tell that they were seeing four different snakes.

All the Bafutians, including the Fon, were fascinated by our filming activities, since not long before they had seen their very first cinema. A mobile ciné van had come out to Bafut and shown them a colour film of the Coronation and they had been terribly thrilled with it. In fact it was still a subject of grave discussion when we were there, nearly a year and a half later. Thinking that the Fon and his council would be interested to learn more about filming, I invited them to come across one morning and attend a filming session and they accepted with delight.

‘What are you going to film?’ asked Jacquie.

‘Well, it doesn’t really matter, so long as it’s innocuous,’ I said.

‘Why innocuous?’ asked Sophie.

‘I don’t want to take any risks … If I got the Fon bitten by something I would hardly be persona grata, would I?’

‘Good God, no, that would never do,’ said Bob. ‘What sort of thing did you have in mind?’

‘Well, I want to get some shots of those pouched rats, so we might as well use them. They can’t hurt a fly.’

So the following morning we got everything ready. The film set, representing a bit of forest floor, had been constructed on a Dexion stand, one of our specially made nylon tarpaulins had been erected nearby, under which the Fon and his court could sit, and beneath it were placed a table of drinks and some chairs. Then we sent a message over to the Fon that we were ready for him.

We watched him and his council approaching across the great courtyard and they were a wonderful spectacle. First came the Fon, in handsome blue and white robes, his favourite wife trotting along beside him, shading him from the sun with an enormous orange and red umbrella. Behind him walked the council members in their fluttering robes of green, red, orange, scarlet, white and yellow. Around this phalanx of colour some forty-odd of the Fon’s children skipped and scuttled about like little black beetles round a huge, multicoloured caterpillar. Slowly the procession made its way round the Rest House and arrived at our improvised film studio.

‘Morning, my friend,’ called the Fon, grinning. ‘We done come for see dis cinema.’

‘Welcome, my friend,’ I replied. ‘You like first we go have drink together?’

‘Wah! Yes, I like,’ said the Fon, lowering himself cautiously into one of our camp chairs.

I poured out the drinks, and as we sipped them I explained the mysteries of ciné photography to the Fon, showing him how the camera worked, what the film itself looked like and explaining how each little picture was of a separate movement.

‘Dis filum you take, when we go see um?’ asked the Fon, when he had mastered the basic principles of photography.

‘I have to take um for my country before it get ready,’ I said sadly, ‘so I no fit show you until I go come back for the Cameroons.’

‘Ah, good,’ said the Fon, ‘so when you go come back for dis ma country we go have happy time and you go show me dis your filum.’

We had another drink to celebrate the thought of my impending return to Bafut.

By this time everything was ready to show the Fon how one set about making a sequence. Sophie, as continuity girl, wearing trousers, shirt, sun-glasses and an outsize straw hat, was perched precariously on a small camp stool, her pad and pencil at the ready to make notes of each shot I took. Near her Jacquie, a battery of still cameras slung round her, was crouched by the side of the recording machine. Near the set, Bob stood in the role of dramatic coach, armed with a twig, and the box in which our stars were squeaking vociferously. I set up the camera, took up my position behind it and gave the signal for action. The Fon and councillors watched silent and absorbed as Bob gently tipped the two pouched rats out on to the set, and then guided them into the right positions with his twig. I started the camera and at the sound of its high-pitched humming a chorus of appreciative ‘Ahs’ ran through the audience behind me. It was just at that moment that a small boy carrying a calabash wandered into the compound and, oblivious of the crowd, walked up to Bob and held up his offering. I was fully absorbed in peering through the viewfinder of the camera and so I paid little attention to the ensuing conversation that Bob had with the child.

‘Na whatee dis?’ asked Bob, taking the calabash, which had its neck plugged with green leaves,

‘Beef,’ said the child succinctly.

Instead of inquiring more closely into the nature of the beef, Bob pulled out the plug of leaves blocking the neck of the calabash. The result surprised not only him but everyone else as well. Six feet of agile and extremely angry green mamba shot out of the calabash like a jack-in-the-box and fell to the ground.

‘Mind your feet!’ Bob shouted warningly.

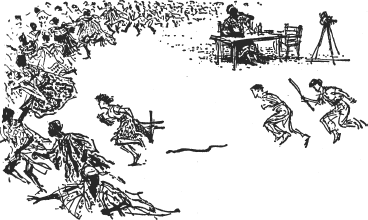

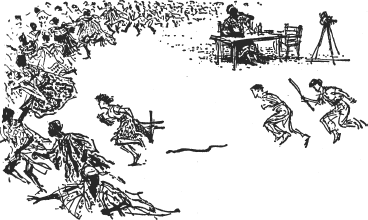

I removed my eye from the viewfinder of the camera to be treated to the somewhat disturbing sight of the green mamba sliding determinedly through the legs of the tripod towards me. I leaped upwards and backwards with an airy grace that only a prima ballerina treading heavily on a tin-tack could have emulated. Immediately pandemonium broke loose. The snake slid past me and made for Sophie at considerable speed. Sophie took one look and decided that discretion was the better part of valour. Seizing her pencil, pad and, for some obscure reason, her camp stool too, she ran like a hare towards the massed ranks of the councillors. Unfortunately this was the way the snake wanted to go as well, so he followed hotly on her trail. The councillors took one look at Sophie, apparently leading the snake into their midst, and did not hesitate for a moment. As one man, they turned and fled. Only the Fon remained, rooted to his chair, so wedged behind the table of drinks that he could not move. ‘Get a stick,’ I yelled to Bob and ran after the snake. I knew, of course, that the snake would not deliberately attack anyone. It was merely trying to put the greatest possible distance between itself and us. But when you have fifty panic-stricken Africans, all bare-footed, running madly in all directions, accompanied by a frightened and deadly snake, an accident is possible. The scene now, according to Jacquie, was fantastic. The council members were running across the compound, pursued by Sophie, who was pursued by the snake, who was pursued by me, who, in turn, was being pursued by Bob with a stick. The mamba had, to my relief, by-passed the Fon. Since the wave of battle had missed him the Fon sat there and did nothing more constructive than help himself to a quick drink to soothe his shattered nerves.

At last Bob and I managed to corner the mamba against the Rest House steps. Then we held it down with a stick, picked it up and popped it into one of our capacious snake-bags. I returned to the Fon, and found the council members drifting back from various points of the compass to join their monarch. If in any other part of the world you had put to flight a cluster of dignitaries by introducing a snake into their midst, you would have had to suffer endless recriminations, sulks, wounded dignity and other exhausting displays of human nature. But not so with the Africans. The Fon sat in his chair, beaming. The councillors chattered and laughed as they approached, clicking their fingers at the danger that was past, making fun of each other for running so fast, and generally thoroughly enjoying the humorous side of the situation.

‘You done hold um, my friend?’ asked the Fon, generously pouring me out a large dollop of my own whisky.

‘Yes,’ I said, taking the drink gratefully, ‘we done hold um.’

The Fon leaned across and grinned at me mischievously. ‘You see how all dis ma people run?’ he asked.

‘Yes, they run time no dere,’ I agreed.

‘They de fear,’ explained the Fon.

‘Yes. Na bad snake dat.’

‘Na true, na true,’ agreed the Fon, ‘all dis small small man de fear dis snake too much.’

‘I never fear dis snake,’ said the Fon. ‘All dis ma people dey de run … dey de fear too much … but I never run.’

‘No, my friend, na true … you never run.’

‘I no de fear dis snake,’ said the Fon in case I had missed the point.

‘Na true. But dis snake ’e de fear you.’

‘’E de fear me?’ asked the Fon, puzzled.

‘Yes, dis snake no fit bite you … na bad snake, but he no fit kill Fon of Bafut.’

The Fon laughed uproariously at this piece of blatant flattery, and then, remembering the way his councillors had fled, he laughed again, and the councillors joined him. At length, still reeling with merriment at the incident, they left us and we could hear their chatter and hilarious laughter long after they had disappeared. This is the only occasion when I have known a green mamba to pull off a diplomatic coup d’état.