It was time for us to start making preparations to leave Bafut and travel the three-hundred-odd miles down to the coast. But there was a lot to be done before we could set out on the journey. In many ways this is the most harassing and dangerous part of a collecting trip. For one thing to load your animals on to lorries and take them that distance, over roads that resemble a tank-training ground more than anything else, is in itself a major undertaking. But there are many other vital things to arrange as well. Your food supply for the voyage must be waiting for you at the port, and here again you cannot afford to make any mistakes, for you cannot take two hundred and fifty animals on board a ship for three weeks unless you have an adequate supply of food. All your cages have to be carefully inspected and any defects caused by six months’ wear-and-tear have to be made good, because you cannot risk having an escape on board ship. So, cages have to be rewired, new fastenings fixed on doors, new bottoms fitted on to cages that show signs of deterioration, and a hundred and one other minor jobs.

So, taking all this into consideration, it is not surprising that you have to start making preparations for departure sometimes a month before you actually leave your base camp for the coast. Everything, it seems, conspires against you. The local population, horrified at the imminent loss of such a wonderful source of revenue, redouble their hunting efforts so as to make the maximum profit before you leave, and this means that you are not only renovating old cages, but constructing new ones as fast as you can to cope with this sudden influx of creatures. The local telegraph operator undergoes what appears to be a mental breakdown, so that the vital telegrams you send and receive are incomprehensible to both you and the recipient. When you are waiting anxiously for news of your food supplies for the voyage it is not soothing to the nerves to receive a telegram which states, ‘MESSAGE REPLIED REGRET CANNOTOB VARY GREEN BALAS WELL HALF PIPE DO?’ which, after considerable trouble and expense, you get translated as: MESSAGE RECEIVED REGRET CANNOT OBTAIN VERY GREEN BANANAS WILL HALF RIPE DO?

Needless to say, the animals soon became aware that something is in the wind and try to soothe your nerves in their own particular way: those that are sick get sicker, and look at you in such a frail and anaemic way you are quite sure they will never survive the journey down to the coast; all the rarest and most irreplaceable specimens try to escape, and if successful hang around taunting you with their presence and making you waste valuable time trying to catch them again; animals that had refused to live unless supplied with special food, whether avocado pear or sweet potato, suddenly decide that they do not like this particular food any more, so frantic telegrams have to be sent cancelling the vast quantities of the delicacies you had just ordered for the voyage. Altogether this part of a collecting trip is very harassing.

The fact that we were worried and jumpy, of course, made all of us do silly things that only added to the confusion. The case of the clawed toads is an example of what I mean. Anyone might be pardoned for thinking that clawed toads were frogs at first glance. They are smallish creatures with blunt, frog-like heads and a smooth, slippery skin which is most untoad-like. Also they are almost completely aquatic, another untoad-like characteristic. To my mind they are rather dull creatures who spend ninety per cent of their time floating in the water in various abandoned attitudes, occasionally shooting to the surface to take a quick gulp of air. But, for some reason which I could never ascertain, Bob was inordinately proud of these wretched toads. We had two hundred and fifty of them and we kept them in a gigantic plastic bath on the verandah. Whenever Bob was missing, one was almost sure to find him crouched over this great cauldron of wriggling toads, an expression of pride on his face. Then came the day of the great tragedy.

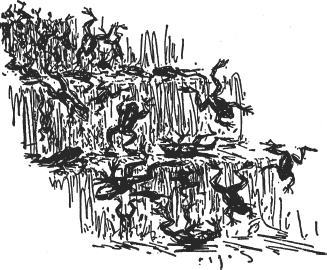

The wet season had just started and the brilliant sunshine of each day was being interrupted by heavy downpours of rain; they only lasted an hour or so, but during that hour the quantity of water that fell was quite prodigious. On this particular morning Bob had been crooning over his clawed toads and when it started to rain he thought that they would be grateful if he put their bowl out in it. So he carefully carried the toads’ bowl down the verandah and placed it on the top step, brilliantly positioned so that it not only received the rain itself but all the water that ran off the roof. Then he went away to do something else and forgot all about it. The rain continued to rain as if determined to uphold the Cameroons’ reputation for being one of the wettest places on earth, and gradually the bowl filled up. As the water level rose so the toads rose with it until they were peering over the plastic rim. Another ten minutes of rain and, whether they wanted to or not, they were swept out of the bowl by the overflow.

My attention was drawn to this instructive sight by Bob’s moan of anguish when he discovered the catastrophe, a long-drawn howl of emotion that brought us all running from wherever we were. On the top step stood the plastic bowl, now completely empty of toads. From it the water gushed down the steps carrying Bob’s precious amphibians. The steps were black with toads, slithering, hopping and rolling over and over in the water. In this Niagara of amphibians Bob, with a wild look in his eye, was leaping to and fro like an excited heron, picking up toads as fast as he could. Picking up a clawed toad is quite a feat. It is almost as difficult as trying to pick up a drop of quicksilver; apart from the fact that their bodies are incredibly slippery, the toads are very strong for their size and kick and wriggle with surprising energy. In addition their hind legs are armed with small, sharp claws and when they kick out with these muscular hind legs they are quite capable of inflicting a painful scratch. Bob, alternately moaning and cursing in anguish, was not in the calm collected mood that is necessary for catching clawed toads, and so every time he had scooped up a handful of the creatures and was bounding up the steps to return them to their bath, they would squeeze from between his fingers and fall back on to the steps, to be immediately swept downwards again by the water. In the end it took five of us three-quarters of an hour to collect all the toads and put them back in their bowl, and just as we had finished and were soaked to the skin it stopped raining.

‘If you must release two hundred and fifty specimens you might at least choose a fine day and an animal that is reasonably easy to pick up,’ I said to Bob bitterly.

‘I can’t think what made me do such a silly thing,’ said Bob, peering dismally into the bowl in which the toads, exhausted after their romp, hung suspended in the water, peering up at us in their normal pop-eyed, vacant way. ‘I do hope they’re not damaged in any way.’

‘Oh, never mind about us. We can all get pneumonia galloping about in the rain, just as long as those repulsive little devils are all right. Would you like to take their temperatures?’

‘You know,’ said Bob frowning, and ignoring my sarcasm, ‘I’m sure we’ve lost quite a lot … there doesn’t seem to be anything like the number we had before.’

‘Well, I’m not going to help you count them. I’ve been scratched enough by clawed toads to last me a lifetime. Why don’t you go and change and leave them alone? If you start counting them you’ll only have the whole damn lot out again.’

‘Yes,’ said Bob, sighing, ‘I suppose you’re right.’

Half an hour later I let Cholmondely St John, the chimp, out of his cage for his morning exercise, and stupidly took my eye off him for ten minutes. As soon as I heard Bob’s yell, the cry of a mind driven past breaking point, I took a hasty look round and, not seeing Cholmondely St John, I knew at once that he was the cause of Bob’s banshee wail. Hurrying out on to the verandah I found Bob wringing his hands in despair, while on the top step sat Cholmondely, looking so innocent that you could almost see his halo gleaming. Half-way down the steps, upside down, was the plastic bowl, and the steps below it and the compound beyond were freckled with hopping, hurrying toads.

We slithered and slipped in the red mud of the compound for an hour before the last toad was caught and put in the bowl. Then, breathing hard, Bob picked it up and in silence we made our way back to the verandah. As we reached the top step Bob’s muddy shoes slipped under him and he fell, and the bowl rolled to the bottom, and for the third time the clawed toads set off joyfully into the wide world.

Cholmondely St John was responsible for another escape, but this was less strenuous and more interesting than the clawed toad incident. In the collection we had about fourteen of the very common local dormouse, a creature that closely resembled the European dormouse, except that it was a pale ash grey, and had a slightly more bushy tail. This colony of dormice lived in a cage together in perfect amity and in the evenings gave us a lot of pleasure with their acrobatic displays. There was one in particular that we could distinguish from all the others for he had a very tiny white star on his flank, like a minute cattle brand. He was a much better athlete than the others and his daring leaps and somersaults had earned our breathless admiration. Because of his circus-like abilities we had christened him Bertram.

One morning, as usual, I had let Cholmondely St John out for his constitutional and he was behaving himself in an exemplary fashion. But a moment came when I thought Jacquie was watching him, and she thought I was. Cholmondely was always on the look-out for such opportunities. When we had discovered our mistake and had gone in search of him we found we were too late. Cholmondely had amused himself by opening the doors of the dormouse sleeping-compartments and then tipping the cage over so that the unfortunate rodents, all in a deep and peaceful sleep, cascaded out on to the floor. As we arrived on the scene they were all rushing frantically for cover while Cholmondely, uttering small ‘Oooo’s’ of delight, was galloping around trying to stamp on them. By the time the ape had been caught and chastised there was not a dormouse in sight, for they had all gone to continue their interrupted slumbers behind our rows of cages. So the entire collection had to be moved, cage by cage, so that we could recapture the dormice. The first one to break cover from behind a monkey cage was Bertram, who fled down the verandah hotly pursued by Bob. As he hurled himself at the flying rodent, I shouted a warning.

‘Remember the tail … don’t catch it by the tail …’ I yelled. But I was too late. Seeing Bertram wriggling his fat body behind another row of cages Bob grabbed him by his tail, which was the only part of his anatomy easily grabbed. The result was disastrous. All small rodents, and particularly these dormice, have very fine skin on the tail, and if you catch hold of it and the animal pulls away the skin breaks and peels off the bone like the finger of a glove. This is such a common thing among small rodents that I am inclined to think it may be a defence mechanism, like the dropping of the tail in lizards when caught by an enemy. Bob knew this as well as I did, but in the excitement of the chase he forgot it, and so Bertram continued on his way behind the cage and Bob was left holding a fluffy tail dangling limply between finger and thumb. Eventually we unearthed Bertram and examined him. He sat plumply in the palm of my hand, panting slightly; his tail was now pink and skinless, revoltingly reminiscent of an ox-tail before it enters a stew. As usual when this happens, the animal appeared to be completely unaffected by what is the equivalent, in human terms, of having all the skin suddenly ripped off one leg, leaving nothing but the bare bone and muscle. I knew from experience that eventually, deprived of skin, the tail would wither and dry, and then break off like a twig, leaving the animal none the worse off. In the case of Bertram, of course, the loss would be a little more serious as he used his tail quite extensively as a balancing organ during his acrobatics, but he was so agile I did not think he would miss it much. But, from our point of view, Bertram was now useless, for he was a damaged specimen. The only solution was to amputate his tail and let him go. This I did, and then, very sorrowfully, we put him among the thick twining stems of the bougainvillaea that grew along the verandah rail. We hoped that he would set up house in the place and perhaps entertain future travellers with his acrobatic feats when he had grown used to having no tail.

He sat on a bougainvillaea stem, clutching it tightly with his little pink paws, and looking about him through a quivering windscreen of whiskers. Then, very rapidly, and apparently with his sense of balance completely unimpaired, he jumped down on to the verandah rail, from there to the floor, and then scurried across to the line of cages against the far wall. Thinking that perhaps he was a bit bewildered I picked him up and returned him to the bougainvillaea. But as soon as I released him he did exactly the same thing again. Five times I put him in the bougainvillaea and five times he jumped to the verandah floor and made a beeline for the cages. After that, I tired of his stupidity and carried him right down to the other end of the verandah, put him once more in the creeper and left him, thinking that this would finish the matter.

On top of the dormouse cage we kept a bundle of cotton waste which we used to change their beds when they became too unhygienic, and that evening, when I went to feed them, I decided that they could do with a clean bed. So, removing the extraordinary treasure trove that dormice like to keep in their bedrooms, I pulled out all the dirty cotton waste and prepared to replace it with clean. As I seized the bundle of waste on top of the cage, preparatory to ripping off a handful, I was suddenly and unexpectedly bitten in the thumb. It gave me a considerable shock, for not only was I not expecting it, but I also thought for a moment that it might be a snake. However, my mind was quickly set at rest for as soon as I touched the bundle of cotton waste an indignant face poked out of its depths and Bertram chittered and squeaked at me in extremely indignant terms. Considerably annoyed, I hauled him out of his cosy bed, carried him along the verandah and pushed him back into the bougainvillaea. He clung indignantly to a stem, teetering to and fro and chittering furiously. But within two hours he was back in the bundle of cotton waste.

Giving up the unequal struggle we left him there, but Bertram had not finished yet. Having beaten us into submission over the matter of accommodation, he started to work on our sympathies in another direction. In the evening, when the other dormice came out of their bedroom and discovered their food plate with squeaks of surprise and delight, Bertram would come out of his bed and crawl down the wire front of the cage. There he would hang, peering wistfully through the wire, while the other dormice nibbled their food and carried away choice bits of banana and avocado pear to hide in their beds, a curious habit that dormice have, presumably to guard against night starvation. He looked so pathetic, hanging on the wire, watching the others stagger about with their succulent titbits, that eventually we gave in, and a small plate of food was placed on top of the cage for him. At last his cunning served its purpose: it seemed silly, since we had to feed him, to let him live outside, so we caught him and put him back in the cage with the others, where he settled down again as if he had never left. It merely seemed to us that he looked a trifle more smug than before. But what other course could one adopt with an animal that refused to be released?

Gradually we got everything under control. All the cages that needed it were repaired, and each cage had a sacking curtain hung in front, which could be lowered when travelling. The poisonous-snake boxes had a double layer of fine gauze tacked over them, to prevent accidents, and their lids were screwed down. Our weird variety of equipment – ranging from mincers to generators, hypodermics to weighing machines – was packed away in crates and nailed up securely, and netting film tents were folded together with our giant tarpaulins. Now we had only to await the fleet of lorries that was to take us down to the coast. The night before they were due to arrive the Fon came over for a farewell drink.

‘Wah!’ he exclaimed sadly, sipping his drink, ‘I sorry too much you leave Bafut, my friend.’

‘We get sorry too,’ I replied honestly. ‘We done have happy time here for Bafut. And we get plenty fine beef.’

‘Why you no go stay here?’ inquired the Fon. ‘I go give you land for build one foine house, and den you go make dis your zoo here for Bafut. Den all dis European go come from Nigeria for see dis your beef.’

‘Thank you, my friend. Maybe some other time I go come back for Bafut and build one house here. Na good idea dis.’

‘Foine, foine,’ said the Fon, holding out his glass.

Down in the road below the Rest House a group of the Fon’s children were singing a plaintive Bafut song I had never heard before. Hastily I got out the recording machine, but just as I had it fixed up, the children stopped singing. The Fon watched my preparations with interest.

‘You fit get Nigeria for dat machine?’ he inquired.

‘No, dis one for make record only, dis one no be radio.’

‘Ah!’ said the Fon intelligently.

‘If dis your children go come for up here and sing dat song I go show you how dis machine work,’ I said.

‘Yes, yes, foine,’ said the Fon, and roared at one of his wives who was standing outside on the dark verandah. She scuttled down the stairs and presently reappeared herding a small flock of shy, giggling children before her. I got them assembled round the microphone and then, with my fingers on the switch, looked at the Fon.

‘If they sing now I go make record,’ I said.

The Fon rose majestically to his feet and towered over the group of children.

‘Sing,’ he commanded, waving his glass of whisky at them.

Overwhelmed with shyness the children made several false starts, but gradually their confidence increased and they started to carol lustily. The Fon beat time with his whisky glass, swaying to and fro to the tune, occasionally bellowing out a few words of the song with the children. Presently, when the song came to an end he beamed down at his progeny.

‘Foine, foine, drink,’ he said, and as each child stood before him with cupped hands held up to their mouths he proceeded to pour a tot of almost neat whisky into their pink palms. While the Fon was doing this I wound back the tape and set the machine for playback. Then I handed the earphones to the Fon, showed him how to adjust them, and switched on.

The expressions that chased one another across the Fon’s face were a treat to watch. First there was an expression of blank disbelief. He removed the headphones and looked at them suspiciously. Then he replaced them and listened with astonishment. Gradually as the song progressed a wide urchin grin of pure delight spread across his face.

‘Wah! Wah! Wah!’ he whispered in wonder, ‘na wonderful, dis.’ It was with the utmost reluctance that he relinquished the earphones so that his wives and councillors could listen as well. The room was full of exclamations of delight and the clicking of astonished fingers. The Fon insisted on singing three more songs, accompanied by his children, and then listening to the playback of each one, his delight undiminished by the repetition.

‘Dis machine na wonderful,’ he said at last, sipping his drink and eyeing the recorder. ‘You fit buy dis kind of machine for Cameroons?’

‘No, they no get um here. Sometime for Nigeria you go find um … maybe for Lagos,’ I replied.

‘Wah! Na wonderful,’ he repeated dreamily.

‘When I go for my country I go make dis your song for proper record, and then I go send for you so you fit put um for dis your gramophone,’ I said.

‘Foine, foine, my friend,’ he said.

An hour later he left us, after embracing me fondly, and assuring us that he would see us in the morning before the lorries left. We were just preparing to go to bed, for we had a strenuous day ahead of us, when I heard the soft shuffle of feet on the verandah outside, and then the clapping of hands. I went to the door and there on the verandah stood Foka, one of the Fon’s elder sons, who bore a remarkable resemblance to his father.

‘Hallo, Foka, welcome. Come in,’ I said.

He came into the room carrying a bundle under his arm, and smiled at me shyly.

‘De Fon send dis for you, sah,’ he said, and handed the bundle to me. Somewhat mystified, I unravelled it. Inside was a carved bamboo walking stick, a small heavily embroidered skull cap, and a set of robes in yellow and black, with a beautifully embroidered collar.

‘Dis na Fon’s clothes,’ explained Foka. ‘’E send um for you. De Fon ’e tell me say dat now you be second Fon for Bafut.’

‘Wah!’ I exclaimed, genuinely touched. ‘Na fine ting dis your father done do for me.’

Foka grinned delightedly at my obvious pleasure.

‘Which side you father now. ’E done go for bed?’ I asked.

‘No, sah, ’e dere dere for dancing house.’

I slipped the robes over my head, adjusted my sleeves, placed the ornate little skull cap on my head, grasped the walking stick in one hand and a bottle of whisky in the other, and turned to Foka.

‘I look good?’ I inquired.

‘Fine, sah, na fine,’ he said, beaming.

‘Good. Then take me to your father.’

He led me across the great, empty compound and through the maze of huts towards the dancing house, where we could hear the thud of drums and the pipe of flutes. I entered the door and paused for a moment. The band in sheer astonishment stopped dead. There was a rustle of amazement from the assembled company, and I could see the Fon seated at the far end of the room, his glass arrested half-way to his mouth. I knew what I had to do, for on many occasions I had watched the councillors approaching the Fon to pay homage or ask a favour. In dead silence I made my way down the length of the dance hall, my robes swishing round my ankles. I stopped in front of the Fon’s chair, half crouched before him and clapped my hands three times in greeting. There was a moment’s silence and then pandemonium broke loose.

The wives and the council members screamed and hooted with delight, the Fon, his face split in a grin of pleasure, leapt from his chair and, seizing my elbows, pulled me to my feet and embraced me.

‘My friend, my friend, welcome, welcome,’ he roared, shaking with gusts of laughter.

‘You see,’ I said, spreading my arms so that the long sleeves of the robe hung down like flags, ‘You, see, I be Bafut man now.’

‘Na true, na true, my friend. Dis clothes na my own one. I give for you so you be Bafut man,’ he crowed.

We sat down and the Fon grinned at me.

‘You like dis ma clothes?’ he asked.

‘Yes, na fine one. Dis na fine ting you do for me, my friend,’ I said.

‘Good, good, now you be Fon same same for me,’ he laughed.

Then his eyes fastened pensively on the bottle of whisky I had brought.

‘Good,’ he repeated, ‘now we go drink and have happy time.’ It was not until three thirty that morning that I crawled tiredly out of my robes and crept under my mosquito net.

‘Did you have a good time?’ inquired Jacquie sleepily from her bed.

‘Yes,’ I yawned. ‘But it’s a jolly exhausting process being Deputy Fon of Bafut.’

The next morning the lorries arrived an hour and a half before the time they had been asked to put in an appearance. This extraordinary circumstance – surely unparalleled in Cameroon history – allowed us plenty of time to load up. Loading up a collection of animals is quite an art. First of all you have to put all your equipment into the lorry. Then the animal cages are placed towards the tailboard of the vehicle, where they will get the maximum amount of air. But cages cannot be pushed in haphazardly. They have to be wedged in such a way that there are air spaces between each cage, and you have to make sure that the cages are not facing each other, or during the journey a monkey will go and push its hand through the wire of a cage opposite and get itself bitten by a civet; or an owl (merely by being an owl and peering), if placed opposite a cage of small birds, will work them into such a state of hysteria that they will probably all be dead at the end of your journey. On top of all this you must pack your cages in such a way that all the stuff that is liable to need attention en route is right at the back and easily accessible. By nine o’clock, the last lorry had been loaded and driven into the shade under the trees, and we could wipe the sweat from our faces and have a brief rest on the verandah. Here the Fon joined us presently.

‘My friend,’ he said, watching me pour out the last enormous whisky we were to enjoy together, ‘I sorry too much you go. We done have happy time for Bafut, eh?’

‘Very happy time, my friend.’

‘Shin-shin,’ said the Fon.

‘Chirri-ho,’ I replied.

He walked down the long flight of steps with us, and at the bottom shook hands. Then he put his hands on my shoulders and peered into my face.

‘I hope you an’ all dis your animal walka good, my friend,’ he said, ‘and arrive quick-quick for your country.’

Jacquie and I clambered up into the hot, airless interior of the lorry’s cab and the engine roared to life. The Fon raised his large hand in salute, the lorry jolted forward and, trailing a cloud of red dust, we shuddered off along the road, over the golden-green hills towards the distant coast.

The trip down to the coast occupied three days, and was as unpleasant and nerve-racking as any trip with a collection of animals always is. Every few hours the lorries had to stop so that the small bird cages could be unloaded, laid along the side of the road, and their occupants allowed to feed. Without this halt the small birds would all die very quickly, for they seemed to lack the sense to feed while the lorry was in motion. Then the delicate amphibians had to be taken out in their cloth bags and dipped in a local stream every hour or so, for as we got down into the forested lowlands the heat became intense, and unless this was done they soon dried up and died. Most of the road surfaces were pitted with potholes and ruts, and as the lorries dipped and swayed and shuddered over them we sat uncomfortably in the front seats, wondering miserably what precious creature had been maimed or perhaps killed by the last bump. At one point we were overtaken by a heavy rainfall, and the road immediately turned into a sea of glutinous red mud, that sprayed up from under the lorry wheels like blood-stained porridge; then one of the lorries – an enormous four-wheel-drive Bedford – got into a skid from which the driver could not extricate himself, and ended on her side in the ditch. After an hour’s digging round her wheels and laying branches so that her tyres could get a grip, we managed to get her out; and fortunately none of the animals were any the worse for their experience.

But we were filled with a sense of relief as the vehicles roared down through the banana groves to the port. Here the animals and equipment were unloaded and then stacked on the little flat-topped railway waggons used for ferrying bananas to the side of the ship. These chugged and rattled their way through half a mile of mangrove swamp and then drew up on the wooden jetty where the ship was tied up. Once more the collection was unloaded and stacked in the slings, ready to be hoisted aboard. On the ship I made my way down to the forward hatch, where the animals were to be stacked, to supervise the unloading. As the first load of animals was touching down on the deck a sailor appeared, wiping his hands on a bundle of cotton waste. He peered over the rail at the line of railway trucks, piled high with cages, and then he looked at me and grinned.

‘All this lot yours, sir?’ he inquired.

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘and all that lot down on the quay.’

He went forward and peered into one of the crates.

‘Blimey!’ he said, ‘These all animals?’

‘Yes, the whole lot.’

‘Blimey,’ he said again, in a bemused tone of voice, ‘You’re the first chap I’ve ever met with a zoo in his luggage.’

‘Yes,’ I said happily, watching the next load of cages swing on board, ‘and it’s my own zoo, too.’