During the Civil War, the boundary separating Tennessee and Kentucky was one of the most hotly contested regions in North America. What the Confederate States sought to defend as an international border the United States worked to prove moot. Champ Ferguson, a forty-year-old farmer, lived just north of this all-important line. Having been born and reared in Clinton County, Kentucky, Ferguson was acutely aware of his proximity to Tennessee and, like others of his region, crossed the border frequently for social and economic reasons. However, the interstate border that could be taken for granted became a much more rigid dividing line once the Civil War began. For Ferguson, like many of his borderland neighbors, the border became emblematic of the internal struggle of a people beset by war. With sometimes-mortal questions of loyalty, exhibitions of partisan violence, and a perpetual instinct for self-preservation, this man, whose first documented case of violence was in 1858, became one of the most notorious guerrilla warriors of the Civil War.

To be fair, the die was cast for Champ Ferguson to join the Confederacy from the moment Tennesseans began forming Southern armies. During the late spring of 1858, Champ, along with several of his Clinton County neighbors, sold a large herd of livestock to the Evans brothers from nearby Fentress County, Tennessee. Taking a promissory note properly notarized by several of that county’s leading citizens, the Kentuckians felt confident that they would see their money. However, one of the brothers ran off with the stock, and the signers of the note claimed their signatures to be clever forgeries. Ferguson and another investor filed suit in Overton County, Tennessee, and won the case, but that money would never be collected. As Kentuckians, however, the men could take advantage of a Kentucky state law that allowed confiscation of personal property to repay a debt, so Champ and his fellows began coming into Tennessee under cover of darkness to take horses and other valuable property. However legal in Kentucky, this was simple theft in Tennessee, and, in the summer of 1858, the Evanses and several of their neighbors ambushed Ferguson at a camp meeting in Fentress County, Tennessee. In the running fight that ensued, Champ killed a county constable and was later arrested and remanded to the jail at Jamestown, Tennessee. Over the course of the next two years, Ferguson, with the help of his able attorney, Willis Scott Bledsoe, petitioned for and received extension after extension while awaiting trial at home. By the time Tennessee seceded from the Union nearly three years later, Champ had still not stood trial for the killing of the constable. During this time, fortune stepped in. When Ferguson’s attorney declared himself for the Confederacy, he apparently promised his client that, with a Southern victory in the impending war, the case would be lost to history. Bolstering this theory, Ferguson noted that he was “induced to join the army on the promise that all prosecution in that case would be abandoned.”1

Like countless other residents of the Tennessee-Kentucky borderland, Champ Ferguson awoke one morning and found himself living in an enemy’s country. In mid-August 1861, Capt. John W. Tuttle of the Third Kentucky Volunteer Infantry (USA) entered Albany, Kentucky, the seat of Ferguson’s home county of Clinton, and recorded the citizens’ overwhelming Union sentiment. He saw “the stars and stripes gaily fluttering to the breze [sic] above the tops of the houses” and noted that more than two thousand people had turned out for the military parade through Albany’s streets. That day, Champ came to town with his brother Jim to hear what the pro-Union speakers had to say. Although his legal woes had already dictated which path Champ would take, Jim listened intently to the speeches and later joined the Union army, as did their younger brother Ben. The remaining members of the family openly supported the Union cause and ostracized Champ after his commitment to the Confederacy threatened much of the family’s wealth, which had been put forth to secure his bond.2

Calm and serious with slouched shoulders, Champ Ferguson does not look like one of the Civil War’s most formidable guerrilla warriors. Courtesy of the Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky.

By September, the situation in Clinton County had deteriorated to the point that anyone not completely behind the cause for Union lived in fear. This put Champ clearly in the sights of his Unionist neighbors, and, in late August 1861, the pro-Union Kentuckians made their move. Meeting Ferguson on the road, a small group arrested him and set out on the road to the Federal recruiting center, Camp Dick Robinson, Kentucky. After traveling a few days, Ferguson escaped his captors on realizing that his continuing to live in Kentucky would breed more of these events. The increasingly personal nature of the war, along the borderline, affected Ferguson in much the same way that it did numerous others. For Champ, it caused him to move his family south into Tennessee, where they would live among a Confederate majority. His arrest also made him rethink his own personal safety. When captured, he was carrying only an old pepperbox revolver. From that point forward, he never traveled without formidable arms.3

Now that he was openly a Confederate, Ferguson began to participate actively in the war as a partisan guerrilla. Having neither military training nor a complete idea of the motives, objectives, or rules of war, he interpreted them for himself as: armies fight to kill the enemy; therefore, enemies, once identified as such, were fair targets and were to be vanquished however and whenever possible. In early November, Champ killed his first man of the war. His victim was William Frogg, a Unionist who had known Ferguson for most of his life. Invited into the house by Frogg’s wife, Ferguson found the man bedridden with measles. Understanding the source of Frogg’s malady as Camp Dick Robinson, the major Union recruiting depot in Kentucky, Champ matter-of-factly accused Frogg of being a member of the Union army. The ill man responded that he had visited the camp but had not joined the army. However, Ferguson was not convinced. He pulled a gun and killed Frogg in his sickbed with a five-month-old child in a crib next to him. This bloody and apparently premeditated event seems illogical, but, to Ferguson, it was perfectly reasoned. Seeing the world as black and white with no shades of gray, he considered any man who was not an ally an enemy. He even defended his apparent cowardice in shooting a bedridden and unarmed man by stating that Frogg was a bigger man than he and, if permitted to recover, would “waylay and shoot me.” In Ferguson’s mind, his killing of Frogg was, as he would defend several other killings, a preemptive strike. “I took time by the forelock, as people say. . . . I thought there was nothing like being in time,” he said, “[because,] if we did not, we would soon find ourselves in a snare.”4

Indeed, the borderland region became a netherworld essentially devoid of civil authority. No single event illustrates this point better than Ferguson’s behavior on December 2, 1861, when he stood in front of the Clinton County courthouse and stole a man’s horse while calling him “a God-damned Lincolnite” and imploring him to show himself so Ferguson could kill him. With the owner safely out of sight, Ferguson mounted the animal and rode out of town en route to the Wood farm.5

Reuben Wood had been one of Champ’s oldest friends, the one who, indeed, had been credited with keeping rogues from shooting him on his arrest for killing the constable in 1858. However, that history did not matter to Champ. He met Wood on the road and asked, “I suppose you have been to Camp Robinson.” When Wood answered affirmatively, Ferguson berated him for several minutes before pulling his gun. The man begged Ferguson and reminded him of their friendship, asking, “Has there ever been any misunderstanding between us?” Ferguson responded coldly, “No, Reuben, you have always treated me like a gentleman, but you have been to Camp Robinson, and I intend to kill you.” With that, Ferguson shot Wood in the abdomen, but the sixty-year-old man stayed upright. Clutching his coat around him, Wood ran around the corner of the house and then inside. There, in the darkened room, he grabbed a hatchet and lay in wait next to the door he had entered, expecting Ferguson to follow him. However, Champ came in the front, but still could not see Wood because of the darkness of the room. When Ferguson came close, Wood attacked him with the hatchet, and the two men ended up on a bed with Wood and his hatchet on top and getting the best of Champ and his revolver. Knocking the gun out of Champ’s hand, Wood struck him in the head several times before being forced off by one of the guerrilla’s companions. For the next several days, the dying Wood told and retold his story, and, for weeks afterward, Ferguson sported a bandage.6

By the end of 1861, Ferguson had cultivated such a brutal reputation that he could no longer spend any considerable time in his home state of Kentucky. He and his family now lived near Sparta, in White County, Tennessee, and his operations began taking on a more dangerous tone as he had sown seeds of retribution among the Unionists of Clinton County and those family members left behind by his violence. For the remainder of the conflict, he was pursued, not only by the Union army, but also by the sons of the men he had killed.

The new year brought about a change in the nature of the war along the Tennessee-Kentucky border. In January, Confederate forces suffered a serious defeat at Mill Springs, forcing them to abandon Kentucky. Ferguson too began to change. His assaults had already begun to include robbery, but, with the banishment of the Confederate army from south-central Kentucky, any activity that might serve to weaken or even inconvenience the Union and its supporters became part of the borderland war.

Although desperation often drove these partisan acts, they usually had a great impact on the local population by undermining civil authority. During the Civil War, enemies both in uniform and in civilian clothing burned numerous borderland courthouses. In other cases, tax rolls and other official documents were ceremoniously dumped into the street and set afire for all to see. Apart from the more formalized assaults on local government, crimes against individuals in the forms of violence and theft also became popular as the border region became more of a no-man’s land. Ultimately, such behavior did little to change the face of the war and made no noticeable impact on the outcome, but it did tear at the fabric of society—so much so that, in the months that followed the close of the war, numerous Kentucky counties petitioned the state government to call out the militia. In Harlan County, Kentucky, one citizen wrote: “Gurillas [sic] has nearly laid waste to the county by pillaging, plundering, and robbing and . . . are all well armed and men of the worst character and the Civil Authorities cannot apprehend them.” Even John Hunt Morgan, who had enjoyed widespread celebrity and enduring respect for much of the Civil War, sank to bank robbery toward the end of his military operations.7

The turmoil that resulted from local guerrilla operations caused the rise of a core of opposition. In Ferguson’s area of operation, several men rose to prominence as the defenders of Unionism and those who subscribed to it. Most notable was Champ’s brother Jim, who had joined the Union army and served as a scout into his home region until he was killed in an ambush in December 1861. A second brother, Ben, espoused the cause of Union, although he did not join the army. Shortly after Jim’s death, one of Champ’s closest associates shot Ben in the shoulder during a dispute. Curiously, at least to modern sensibilities, Champ remained close with his pro-Confederate friend and expressed little concern for his wounded pro-Union brother.8

Such activities smack of what modern readers might call terrorism. Champ Ferguson clearly operated on instinct over evidence and grew famous for his preventive killings. When he “took time by the forelock,” he did so with the paranoid expectation that his victim would have eventually turned on and tried to kill him. He also understood that his fierce reputation could become a formidable weapon because he knew that the same fear that he felt early in the war as a Confederate living in Unionist Clinton County, Kentucky, existed among Unionists in Middle Tennessee. Champ also knew that his violent activities would spawn retributive action and that he, as a guerrilla, could thrive only within a region in flux. Neither a military theorist nor a deep thinker, Ferguson had the two great talents of the successful guerrilla: common sense and caution.

Perhaps the best-known example of violent Unionist opposition came in the form of David Beatty. “Tinker Dave,” as he was commonly known, was one of the best-known Unionist guerrillas in the region and Ferguson’s greatest nemesis. These wartime enemies seemed committed to killing each other during the war and, in at least one case, came together with deadly results. Through the random shots and attempted ambushes, Champ and Dave finally came together late in the war when Champ and several men caught Tinker Dave alone and took him prisoner, although Dave did effect an escape, albeit one in which he was seriously wounded.9

Understanding that the key to controlling any border region was to control the hearts and minds of its inhabitants, several anti-Confederate writers began producing tracts aimed at shoring up local Unionism while advertising the brutality of the war along the border to politicians and generals far removed from the area. James A. Brents, a former major in the Union army who left the service early in the war, wrote of his experiences in The Patriots and Guerillas of East Tennessee and Kentucky. Another local Unionist, J. D. Hale, took on Champ directly. Writing two tracts specifically aimed at revealing the deeds of this nefarious character, Hale hoped to throw light on the brutal nature of the borderland war while bringing pressure to bear on its greatest Confederate practitioner.10

The second year of the war offered hope to the partisan bands of the Cumberland region. In early March 1862, men representing the local Unionist and Confederate bands met in Monroe, Tennessee, to negotiate a compromise that would, they hoped, close the irregular warfare pervading the region. Some of the Southern sympathizers suggested the compromise by stating “to the Union citizens about Monroe, that horse stealing, and raiding about, was a bad business” and proposing “putting a stop to it.” Gathering together, both sides agreed with the assessment and promised that armed partisans would not invade the counties of Clinton, Kentucky, and Overton, Tennessee. James Beatty, the son of Tinker Dave, remembered that the “arrangement was for both parties to go home, lay down their arms, and go to work.” More directly: “The Home Guard was not to pester the [Confederate] soldiers, and we were to be protected, all faring alike.” Despite the hope that the Upper Cumberland might enjoy some level of stability and security, the compromise did not last long. Although his friends had forged the deal, the Confederate captain James McHenry, a man with whom Ferguson often rode, refused to abide by it. Only days after the attempt at peace, McHenry and his men undermined the deal by raiding Clinton County. John Capps, a Confederate soldier, confirmed that Confederates in the region knew about the compromise and added: “We got it into our head to believe that the union men hadn’t went by it.” His simple explanation: “I was a rebel.”11

With the compromise dead and Federal troops pulling out of the region, the level of security for Unionist citizens fell to an unprecedented low. As depredations became daily occurrences, letters pleading for help began pouring into the offices of any authority that might be able to help restore order. J. D. Hale wrote to Senator Andrew Johnson complaining of the local conditions. Fortuitously for the hopeful Unionists, Johnson’s political rise coincided with the increased strife along the border, and, in his first speech as military governor of Tennessee, he devoted much of his attention to the fast-growing guerrilla problem, promising “a terrible accountability” if “their depredations are not stopped.” A letter to Johnson from Isaac Reneau, a minister of the Disciples of Christ, placed Champ at the forefront of the guerrilla problem in the borderland region. At the bottom of the correspondence, the governor wrote: “Reward to be offered for man . . . Champ Ferguson.”12

Although Ferguson made no statement for the historical record regarding his newfound fame, his actions suggested a man who was comfortable with his rising importance. Over the coming months, he continued to prosecute his uniquely bloody form of warfare and added the knife to his trusty gun as a tool of the trade. Fighting in periodic small battles and skirmishes alongside Capt. Oliver Hamilton’s band, he also found time for robbery and intimidation.

In an April 1862 raid into Clinton County, Kentucky, Ferguson and his men found Henry Johnson at home. Ferguson expected that Johnson, a Unionist whose son was active in the area’s anti-Confederate circle, was knowledgeable about several items of Ferguson’s that had been stolen. Riding up in front of the man, Ferguson drew his pistol and demanded that he either have the property returned or pay its value. While at the Johnson place, Ferguson’s men spotted Johnson’s Unionist son fleeing through a distant field. Firing at the younger Johnson, they forced him to jump off a low cliff along the Wolf River. When Ferguson’s men rode to the edge, they could see that the fall had injured Johnson, and they climbed down to the riverbank to finish the job. Farther up the road, they had the good fortune to catch the Union captain John Morrison at home. Despite their hitting Morrison with two bullets and sending him into the woods on foot, he eluded capture that night. Pheroba Hale, the wife of Champ’s nemesis Jonathan Hale, also had a visit from Ferguson during which he and his men strolled through her house taking what they wanted.

On his way out of Kentucky that evening, Ferguson did something that would go far to ensure his bloody reputation. Meeting an armed rider after dark, Champ and his men were surprised to see that a young member of the Unionist home guard had ridden directly into their midst. Sixteen-year-old Fount Zachary immediately turned his gun over to Ferguson’s men when he realized his error, and Champ leveled his weapon and shot the boy. Champ then dismounted with his knife in hand and stabbed the now either dead or dying Zachary in the chest.13 The killing of such a young person pushed Champ’s growing reputation closer to that of a bandit, particularly with the exaggerations that followed during the retellings. One young Union woman recorded in her diary that Champ had killed several men and “cut one in twain,” removing the man’s “intrails and throwing them on a log near by.”14 Several days afterward, the news of the raid had made it as far as Nashville. The Daily Nashville Union reported that Ferguson had taken “a promising little boy, twelve years old, by the name of Zachary” out of his sick bed and that, while held by two guerrillas, “a third cut his abdomen wide open.”15 If Ferguson was not already fully vilified in Union circles, such coverage could certainly ensure that end.

Col. Frank Wolford’s First Kentucky Cavalry (USA) had been sent out of Clinton County only a few weeks before. However, with a recent order having come down to proceed to Nashville, the colonel thought it wise to revisit the county en route to his assignment. With nearly three hundred of Wolford’s men entering Albany, the Union citizens were again free to speak their minds, and they began supplying Wolford with information about the principals. They pointed him south toward Livingston, Tennessee, and, as he moved closer, he gained more information about Champ Ferguson’s whereabouts. On securing Livingston, Wolford gathered a squad to attack Ferguson’s camp, estimated to be four miles south of town. As the small group milled about waiting for their ranks to fill, two more Union soldiers rode up to join the expedition. After a few minutes, the two mounted men began slowly moving off when one of the Union men yelled to his comrades: “Catch them or shoot them . . . it is Champe Ferguson.” Immediately thrust into a race for his life, Champ left his comrade behind as a prisoner of the Federals and galloped off hoping to escape. Weathering several shots in his direction, Ferguson saw his chance, leaped off his horse, and fled on foot through some dense underbrush.16

By early May, Ferguson was back in Kentucky riding with his former attorney, Scott Bledsoe, on what can be considered an advance scout for John Hunt Morgan’s planned invasion of the Bluegrass State. Entering Kentucky several days ahead of Morgan’s scheduled arrival, Ferguson and Bledsoe used their available time to continue prosecuting their violent regional war.17 Morgan’s embarrassing defeat at Lebanon, Tennessee, further slowed his advance, but, within days of the setback, he had regrouped his men and moved into Kentucky. By the time Morgan approached Bowling Green, Ferguson stepped back and turned the lead over to Morgan, who had more experience operating in a broader strategic capacity. For the next four weeks, Champ and his men rode along with Morgan on the guerrilla’s first extended tour of official military duty.18 However, his scout with Morgan proved successful in that it taught him an important lesson by allowing him to operate, however briefly, within the realm of traditional military channels. Also, Ferguson now had a well-respected and militarily legitimate advocate in Morgan, who, Champ expected, could serve him within the army the same way he served Morgan outside it.

Although Ferguson could have officially joined the Confederate army and instantly gained legitimacy, he consciously chose to maintain his independence, which caused some more traditional soldiers considerable concern. Basil Duke, John Hunt Morgan’s brother-in-law and resident martinet, first met Ferguson in July 1862. Duke, having heard many fantastic stories about the man he faced, took time to “impress upon him the necessity of observing—while with us—the rules of civilized warfare.” The poorly educated Ferguson reassured him: “Why Colonel Duke, I’ve got sense.” Then, with his curiosity getting the best of him, Duke inquired of Ferguson the number of men he had killed. Innocently, Ferguson told him: “I ain’t killed nigh as many men as they say I have; folks has lied about me powerful. I ain’t killed but thirty-two men since this war commenced.”19

Whether Ferguson intended it or not, he may have been granted a commission at some point early in the war. During Ferguson’s postwar trial, Gen. Joe Wheeler testified that, typically, the Confederacy did not grant officer commissions specifically to cavalrymen but assumed the commander of any cavalry force to be part of the army when a company was raised and a muster roll submitted.20 John Hunt Morgan’s brother Richard spoke of Ferguson as a commissioned officer when he wrote early in the war: “Capt Ferguson has now reported in accordance with your order which I sent him some time since.” Unimpressed with Ferguson’s preference for “roaming where he has been for some time under the pretext of trying to capture Tinker Dave . . . to steal horses & Negroes & sell them,” he asked his brother: “If you can do so I would much prefer that you assign [them to] some other Co.”21

Many years later, Basil Duke contradicted Richard Morgan when he commented: “Ferguson could hardly be called a bushwhacker, although in his methods he much resembled them.” His men were “very daring fighters” and, “although not enlisted in the Confederate service, were intensely attached to Ferguson and sworn to aid the Southern cause.” Duke respected the fact that, “while Ferguson undertook many expeditions on his own private account and acknowledged no obedience to Confederate orders generally,” he behaved properly while serving with him and “strictly obeyed commands and abstained from evil practices.”22

Bushwhacking, although not possessing a universal definition within Civil War circles, was the most fearsome of ambushes but universally frowned on by professional and semiprofessional soldiers. Hidden among undergrowth, or lying along the tops of low ridges overlooking frequented roads, sharpshooters would take their rifles and draw down on enemies traveling either alone or in small groups. Once the bushwhacker fired, he fled, leaving the terrorized party to guess from whence the shot came. In an area such as the Appalachian Mountains, this was the most common way for the average citizen to participate in the war. Ferguson was no bushwhacker, however. He chose not to sneak and avoid detection, nor did he make any real attempt to hide his identity or motives. Ferguson rode as a partisan and guerrilla, standing somewhere between the common bushwhacker and the mustered soldier.

In late 1862, Champ took advantage of the Confederacy’s invasion of Kentucky to act more aggressively in his own personal war. On one raid in particular, his motivations and tactics come together to help explain his view of the Civil War. Early one morning in October, he and his men stopped at a farm where they proceeded to kill three men. While two were shot to death, the third had been knifed by Ferguson in fulfillment of an earlier promise to “cut your throat with this knife.”23 However, the personal nature of this killing was enhanced by mutilation. Having stabbed the man to death, Ferguson apparently then cut a cornstalk and planted it in one of the wounds for visual effect. Despite this disturbing turn of events, Ferguson recalled the incident and matter-of-factly dismissed it as an act of self-defense. “I killed men to get them out of the way, only; I took no pleasure in torturing them.” He explained: “Delk had been pursuing me a long time, and knew the only way to save my life, was to kill him, and I did it.”24 Ferguson would claim self-defense several times during his bloody career.

By late December, the Confederate invasion of Kentucky was over, and the Southern army had retreated into Tennessee. Knowing that William Rosecrans was readying his Union army for a counter offensive, Braxton Bragg ordered John Hunt Morgan to reenter Kentucky and operate behind enemy lines.25 Again using Champ Ferguson and his men to guide them through the mountain passes into central Kentucky, Morgan’s cavalry embarked on its Christmas Raid. With his primary target being Rosecrans’s lifeline, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, Morgan’s men spent the coming two weeks destroying more than twenty-two hundred feet of bridges, thirty-five miles of track, and many depots, water towers, and army stores.26

While Morgan operated against the Union army, Ferguson took the opportunity to return to the prosecution of his personal war. Once the Confederate force made it through the mountains, he asked for permission to take two companies of Morgan’s men to search out area guerrillas. Morgan agreed, and Champ took off in search of Elam Huddleston, one of the region’s most steadfast Unionists. Shortly before midnight on December 31, 1862, Ferguson and his men quietly encircled the Huddleston house.27 Moses Huddleston, Elam’s brother and a private in the Union army, awoke to see Ferguson glaring at him through a window. “Damn you, we’ve got you now,” Champ screamed. The terrified occupants grabbed their guns, ran upstairs to the second floor, and began peppering the darkness with shots. While the Huddlestons fired out the windows, some of Ferguson’s men sneaked close enough to the house to set fires, hoping to drive out the occupants with either flames or smoke. After about an hour of exchanging shots, Elam Huddleston was hit and severely wounded. Hoping to save his brother’s life, Moses offered to surrender, and one of Morgan’s captains who had ridden along with Ferguson assured the man that they would not be harmed if they would throw down their weapons and exit the house. John Weatherred remembered that Champ “broke in the door and rushing upstairs and came dragging Capt. E. Huddleston down the stairs and out in the yard.” Once outside, Champ pulled his pistol and killed the man.28

Leaving Huddleston’s place, the small column, guided by the captured Moses Huddleston, moved toward the Rufus Dowdy farm. Although Rufus Dowdy was not home that night, his two brothers, Allen and Peter Zachary, who were Union soldiers, were there. Pushing the door in, the Confederates poured into the small room where the men were sleeping. Terrified, one of the soldiers grabbed his pistol and fired at Champ from point-blank range, narrowly missing the guerrilla leader. A fierce hand-to-hand fight ensued during which one of the Union soldiers was shot as he tried to make his escape out the front door and the other ran out into the front yard with Champ stabbing him along the way. That night, both Zachary brothers died at the hands of Ferguson and his men, only six months after Ferguson had killed their father and younger brother in a similar night attack on the home.29

When Ferguson and Morgan returned to Tennessee, the guerrilla receded into his surroundings until the summer. In July, however, Morgan embarked on his ill-fated Ohio Raid. However, Champ Ferguson was fortuitously absent from this expedition, which would, ultimately, result in the capture of Morgan and hundreds of his men. Later, during his courtmartial, Champ admitted that he and Morgan had a falling out on the eve of the raid because “he took forty of my men and I was left with only a small force.”30 Although Ferguson had found a military patron in Morgan, he was not willing to allow that relationship to infringe on his own personal war. Since he had moved out of Kentucky early in the war, Ferguson had made his home on Calfkiller Creek, between Sparta and Monterey, in White County, Tennessee. From that location, he could leave the relative safety of home to pursue his activities elsewhere, but, in August 1863, the war visited him.

At daylight on August 9, men of Col. George Dibrell’s Eighth Tennessee Cavalry (CSA) located Union soldiers under Col. Robert Minty just north of Sparta. Dibrell’s men had been camped on his farm at the time, and, as the battle broke out, the surprised Confederates retreated to a small hill overlooking the only local bridge across Wild Cat Creek. The Battle of Wild Cat Creek, or Meredith’s Mill, was a rousing Confederate success on several fronts. Dibrell’s men rebuffed three attempts by a Union force twice its size to cross the creek, and once Minty pulled part of his men away to ford the stream in a flanking movement. Having done his damage, Dibrell pulled his men back into town, where they enjoyed a breakfast cooked by the women of Sparta. Sharing in the celebration that day was Champ Ferguson, who had arrived during the heat of the battle leading a collection of his own men and townsmen.31 It seems that, since Ferguson had lost his connection with Morgan, he was now trying to foster one with another legitimately commissioned commander.

The new year of 1864 saw Ferguson’s elevation to the level of a Union priority. Although the politicians in Nashville had known his name for some time, the generals Ulysses Grant and George Thomas were beginning to take note of his activities. On January 4, Col. Thomas Harrison and two hundred men of the Eighth Indiana followed the Calfkiller River into Sparta. After a five-day expedition filled with small skirmishes, Harrison left the area with a handful of prisoners, but no guerrilla leaders.32 The next Union commander into White County was Col. William Stokes. “Wild Bill of the Hills” led two hundred of his men from the Fifth Tennessee Cavalry up the Calfkiller, camping near Ferguson’s house, and into Sparta. By the end of the expedition, his men had killed “17 of the worst men in the country,” and “took 12 prisoners, and captured about 20 horses and mules.” In closing, Stokes assured his headquarters: “It will take some time and continued scouting to break up these bands, but . . . no time will be lost and no effort spared to rid the country of them.”33

Almost immediately on the departure of the initial Union expeditions, Champ Ferguson emerged from the hills with vengeance on his mind. On February 13, he and his men fought with a group of the Union partisan Rufus Dowdy’s men in Fentress County, killing “three, four, or five.” From that small fight, Ferguson’s men rode on and found more enemies only a mile away. Finding three prominent Unionists at a nearby farm, Ferguson killed two, while the other was escorted away, presumably to his death.34 One witness recalled that Ferguson chillingly made Dallas Beatty, the son of Champ’s nemesis Tinker Dave Beatty, look down the barrel of the gun and asked if he would like to eat the powder just before he fired.35

Within days, Ferguson and the other partisan bands were back in the vicinity of Sparta, followed closely by Colonel Stokes. Now commanding six companies of the Fifth Tennessee Cavalry, Stokes moved into town and quartered his men in Sparta’s deserted houses. Having “barricaded the streets strongly, and fortified around my artillery,” the colonel was prepared to comb the guerrillas out of White County. This task would not be easy, however, as Stokes reported: “The country is infested with a great number of rebel soldiers.” Additionally, he noted that the guerrillas had virtually stopped their plundering, instead turning their attention and efforts toward Federal soldiers venturing into the countryside in search of food and forage.36

At this time, Col. John Hughs, a man with whom Ferguson often worked, commanded around six hundred Confederates equipped with excellent arms taken during one of their raids into Kentucky. On February 22, some of his troopers got an opportunity to meet their enemy. Stokes had sent two companies up the Calfkiller River through the Dug Hill community of White County on a scouting operation. W. B. Hyder recalled that Ferguson and Hughs divided their force and sent the men into the bushes, where they lay in wait for the approaching Federals. When a young captain led his men into “this Narrow Place between the River and the hill,” the Confederates blocked the road in front and behind. Trapped by a much larger force with only sixty men of his own, Hyder suggested that the captain entertain the idea of surrendering but deferred when he saw “their [sic] would be no quarters showed.” Completely trapped, he ordered his men to “bust through the Rebel Ranks as it was nothing but Death anyway.”37

The Battle of Dug Hill,38 as it would become known, was a slaughter. With their quarry trapped in the gorge, the Confederates began cutting them to pieces from their superior positions, at one point even rolling down large rocks and throwing smaller ones on the men of the Fifth Tennessee.39 That day, Hughs counted forty-seven of the enemy killed, thirteen wounded, and four taken prisoner, while he lost only two men wounded.40 Hyder remembered: “The Rebels then Cut the throats of the Boys from Ear to Ear. It was every Man for him selfe.” By the next day, Stokes clearly saw the completeness of his defeat. He reported that all six of his officers and forty-five men had made it through the hills back to town.41 Hyder offered more detail: “They took to the Woods and Brush . . . Scattered all over the Neighborhood and worked they [their] way Back to Sparta sum of them changing their Clothes for Citizens Clothes in order to git on to Sparta.”42 The Battle of Dug Hill, although numerically small and strategically insignificant, illustrated to the Federal army that the guerrilla menace would not cease to exist in the Cumberland region despite the other Union successes throughout Tennessee.

On March 11, Hughs and Ferguson met another Federal force near the location of the Battle of Dug Hill. That day, Ferguson sustained a serious wound. An ecstatic Nashville Daily Union reported on March 29, 1864, that he had been “shot through the abdomen and mortally wounded and at first secreted in a cave.” The information originated from a local physician who dressed the wounds and was later found and questioned by Colonel Stokes. W. B. Hyder, who was probably on the scene during the battle, wrote: “Old Champ charged up and on their Horses fired out all of their shots from their pistals[.] But the boys in the Blue held to their trees and stumps and Champ fell Back out of Gun Shot and reloaded and here they came again hard as their horses could run yelling like wildmen came up in a few steps & Old Champ spoke in a loud coarse voice to Blackman and said Surrender or I will Kill you and Blackman hollered out to him Go to Hell God Dam you.” At that point, some of the Federal soldiers fired at the guerrilla, and he “sunk down on his Saddle and turned his horse and ran off.” Unaware of the extent of Ferguson’s wound, Colonel Stokes called for Hyder two days later and informed him that, if Champ was seriously wounded, he would not go far and that the local doctor would probably have been called to treat him. Stokes sent Hyder “their to Night With 50 Men and take the old Doctor out and Maik him tell where Champ is and if he Refuses to tell Maik him think that you are a going to hang him.” Cautioning Hyder not to “hang him till he is ded,” Stokes instructed the scout that he did not want the man killed, just frightened into giving the required information.43 After the doctor informed Hyder and the others of Ferguson’s whereabouts, the men went to a cave where they only found his empty bed.44

By March 27, the news became more dramatic as the Nashville Daily Union reported that Ferguson had been killed in the fracas. The story recounted how Ferguson’s men had scattered but were hunted down by the Federals: “Whenever one was taken, he was shot without ceremony.” Although the newspaper claimed that Stokes did not know the wounded Ferguson’s whereabouts, it reported that one of Ferguson’s own men betrayed the guerrilla chieftain. Fabricating a story about a captured soldier who begged for his life and managed to broker a deal with Stokes in exchange for Ferguson, the paper reported that the turncoat informed on his captain and that the colonel quickly dispatched a scout to the appointed house. The Federals “entered and found Ferguson lying on a bed in one of the rooms, suffering from the wound received the day before.” On orders from Stokes: “They immediately surrounded the bed and riddled his body with pistol balls.”45 Although premature and patently false, other reports confirming his death were published by the newspaper. Its “authentic source” validated the physician’s claim of the severity of the wound, and the newspaper cheerily announced: “Union men will no more be persecuted by him.”46

Although the Nashville newspaper could not have been more wrong about Ferguson’s demise, his injury was indeed life threatening. For more than three months following the fight, Champ seemingly disappeared into thin air. The next year, he remembered being “badly wounded in one of these fights”: “[I] once thought I should die, but the Lord appeared to be on my side; how long he will stay of that way of thinking, I cant tell.”47

By summer, Champ had recovered from his life-threatening wounds and volunteered his services to the Confederate cavalryman Joe Wheeler on his raid from northern Georgia into Middle Tennessee. Retreating back into Georgia and later South Carolina with Wheeler, Champ got “into some trouble with some of the guard” and was arrested. On his release, Wheeler attached him to the command of Col. George Dibrell.48

In early October, Ferguson reunited with Dibrell at Saltville, Virginia, where numerous small Confederate commands had congregated in an attempt to stop the raid of the Union cavalry commander Stephen Burbridge on the Confederacy’s most important saltworks. On the morning of October 2, 1864, the battle began with George Dibrell’s Tennesseans, including Champ Ferguson, facing part of the Fifth U.S. Colored Cavalry. After a day of Federal advances, the battle ended by 5:00 P.M., when the Union cavalry began to run out of ammunition. The two sides settled in for the evening with the Federals preparing for a nighttime retreat and the Confederates anticipating a second attack the next morning.

Early the next morning, the sounds of battle were gone, and so was the remainder of Burbridge’s command. George Dallas Mosgrove would witness the beginning of a new fight. On waking, he “heard a shot, then another and another until the firing swelled to the volume of . . . a skirmish line.” Asking whether the enemy had returned, and being told that it had not, Mosgrove made his way toward the sound of the firing. Finding himself in front of Robertson’s and Dibrell’s positions, he realized: “The Tennesseans were killing negroes. . . . They were shooting every wounded Negro they could find.”49 Edward O. Guerrant echoed and expanded on Mosgrove’s story: “Scouts were sent, & went all over the field, and the continued ring of the rifle, sung the death knell of many a poor Negro who was unfortunate enough not be killed yesterday.” He added: “Our men took no Negro prisoners. Great numbers of them were killed yesterday & today.”50

Although no individual soldier was named in the aforementioned accounts, at Ferguson’s trial in the summer of 1865, Henry Shocker of the Twelfth Ohio Cavalry placed the defendant on the field as an active participant in the slaughter. He recalled: “I saw the prisoner [Ferguson] in the morning pointing his revolver down at the prisoners laying on the field.” Understanding what was taking place, Shocker, who had been wounded the previous evening, crawled out of the path of the slowly approaching Ferguson. Keeping quiet, and probably feigning death, he heard Champ ask his friend Crawford Henselwood “what he was doing there? And why he came down there to fight with the damned niggers.” With that, Ferguson pulled out his pistol and asked Henselwood: “Where will you have it, in the back or in the face?” Henselwood, now begging for his life, could not sway Ferguson. Having heard such pleas many times before, Champ shot the wounded trooper in midplea.51

Still playing dead, Shocker felt Ferguson walk past him and watched him go to a small log building nearby that was serving as a hospital. For several minutes, Shocker lost sight of Ferguson, and, when two harmlesslooking Confederates came near, the wounded Union soldier asked them if they would take him into the hospital. As the two soldiers neared the building with Shocker, Ferguson came out with two black soldiers. “Wait and see what he does with them,” commented one of the men. Shocker testified that Champ took the men several yards away and killed them with a revolver. He then returned to the hospital and took two more, whom he killed in a similar way.52

More insightful was Lt. George Carter’s account. Carter’s Eleventh Michigan Cavalry was separated from the Fifth U.S. Colored Cavalry on the battlefield by the Twelfth Ohio, but, on the morning following the fight, the lieutenant “saw some colored soldiers killed, eight or nine of them.” Recalling that all the Federals on the field were now prisoners and no longer armed, Carter claimed that he then saw several of the prisoners killed. The men doing the killing confused Carter: “I couldn’t tell whether or not citizens or soldiers did the killing of the prisoners, as all seemed to be dressed alike.” Unsurprisingly, the profound breakdown of discipline and command within Confederate ranks that morning was also noted. Carter did not “know that anybody had command” and recalled: “They all appeared to be commanding themselves.”53

Another eyewitness to the events at the makeshift hospital offered similar testimony. William H. Gardner had been a surgeon in the Thirtieth Kentucky Infantry (USA). Either captured by the enemy or left behind by his unit to treat wounded Federals, Gardner was inside the Confederate hospital working when “Ferguson came there with several armed men.” The guerrilla then “took 5 men, privates, wounded (Negroes), and shot them.”54

Ferguson was not finished with the Saltville fight. Long after dark on the night of October 7, four days after the battlefield killings, Ferguson and several others ascended the stairs of Wiley Hall on the campus of Emory and Henry College. The building had been converted to a hospital and was by that time serving wounded prisoners from Saltville. Orange Sells, a member of the Twelfth Ohio Cavalry, recalled three men bursting into his room. With one holding a candle and the others carrying revolvers, they were clearly looking for someone specific. After looking at each prisoner’s face, one of the men said, “There are none of them here,” and left the room. Within seconds, Sells heard gunfire in the room next door, and a black soldier wrapped in a sheet ran frantically into his room.55 Apparently still angered by his experience fighting black troops, Ferguson had found two wounded black soldiers on the second floor and shot them in their beds.56

If a single person could be credited with sending Ferguson to the gallows, it would be Elza Smith. A lieutenant in the Thirteenth Kentucky Cavalry (USA), Smith, a cousin of Ferguson’s first wife, hailed from Clinton County, Kentucky. About 4:00 P.M. the day after Ferguson came to the hospital and killed the two black soldiers he returned. Normally, guards would be stationed in each stairwell to prevent escape attempts, but, after the previous night’s excitement, they were also on the lookout for vigilantes. Attempting to climb one of the stairs, Ferguson was stopped by a Confederate guard. Dr. James B. Murfree, a Tennessean who was assigned to the hospital at Emory and Henry College, remembered that, when the guard told Ferguson and the others that they could not go upstairs, the guerrilla replied that “they would go up the steps in spite of him.” Undeterred, the guard leveled his gun on the small group and warned them not to advance. Without knowing it, the guard, whom Murfree colorfully described as “an Irishman . . . as brave as Julius Caesar,” had accomplished a rare feat by forcing Champ Ferguson to back down. Ferguson, still wanting to go upstairs, but not badly enough to get shot, changed his tack. Leaving the Irish guard, he and his men walked to the other end of the building, where they climbed a different stairwell over the protestations of a less committed guard.57

On the third floor, Champ found the man for whom he was looking. The “badly wounded and perfectly helpless” Lieutenant Smith was lying in a bed in a room with two other ailing prisoners. Though seriously wounded, Smith recognized Ferguson and asked, “Champ, is that you?” Without a word, Ferguson approached the bed while pulling up a gun with one hand and hitting the breech with the other. Asking, “Smith, do you see this?” while leveling the weapon on the soldier, Smith begged, “Champ! For God’s sake, don’t shoot me here.” Pushing the muzzle of the gun to within a foot of Smith’s head, Ferguson pulled the trigger three times before it finally fired. Orange Sells, a soldier in the Twelfth Ohio Cavalry, was in the room when Ferguson entered and watched as Ferguson and another man inspected the wound to make sure that it was mortal before they left.58

Although Confederate authorities wished to prosecute Champ for the hospital killings, his illegitimate status also presented formidable problems. Milton P. Jarrigan, the judge advocate in Abingdon, Virginia, wrote a month later naming Ferguson and William Hildreth as the two central figures in the Emory and Henry murders but judged that “a military court has no jurisdiction over Ferguson and Hildreth.” Unimpressed, Brig. Gen. John C. Vaughn replied: “The outrage committed at Emory Hospital . . . demands the punishment of the offenders.” On his own investigation, Vaughn informed Jarrigan: “Those charged by name left this Dept with [Gen. John S.] Williams’ command which returned to Genl Hood’s army shortly after this act was perpetrated.” In closing, Vaughn wrote: “I respectfully urge that the men Ferguson and Hildreth be arrested and sent to Abingdon for trial.”59 Angry, and embarrassed by the killing of an unarmed and wounded enemy officer, the Confederate major general John C. Breckinridge ordered the arrest of Ferguson and Hildreth, demanding that they return to his department to face justice. On February 8, 1865, they reported to jail at Wytheville, Virginia, where they would remain, awaiting trial, until the waning days of the Confederacy.60 During Ferguson’s and Hildreth’s two-month imprisonment, Breckinridge wrestled with his duty as an army officer and as a protector of the Southern cause. He devoted all the time he could to the investigation of the happenings at Emory and Henry but was also wrapped up in the unfolding drama of the war’s final weeks. Seeking answers from Wheeler, he asked the cavalry commander the question that would ultimately decide Ferguson’s fate: Under whose authority had Ferguson raised his company?

The answer to this plaguing question would not be simple. Responding to both Breckinridge and the court that tried Ferguson later that year, Wheeler claimed to understand that Edmund Kirby Smith had initially allowed the guerrilla to form his band and operate along the Tennessee-Kentucky border. It appears that Ferguson’s legitimacy within Confederate circles was assumed, and only under close scrutiny, such as that of Judge Advocate Jarrigan in Abingdon, did Champ’s unofficial status reveal itself.

On April 5, as Robert E. Lee’s tattered army was retreating across southside Virginia, hoping to reach the railroad at Danville, Brig. Gen. John Echols ordered Ferguson’s release from jail.61 With the Confederacy’s hope quickly fading, Echols likely considered dealing with such mundane business counterproductive in light of the state of the nation. Joseph Wheeler, who had been apprised of Ferguson’s release, credited the difficulty of securing witnesses against the guerrilla as being another factor motivating Echols.62

From his release in early April through much of the month, Ferguson’s whereabouts are unknown. Although Echols had turned him loose with orders to return to Wheeler, the guerrilla would not have had enough time to travel from Wytheville to Georgia or South Carolina, rejoin the fight, and make it back to Middle Tennessee by late April. It is more likely that Ferguson either heard of the Army of Northern Virginia’s demise and returned home or, having become jaded by his arrest and imprisonment, had no intention of returning to the field. Whatever his reason, by late April, Champ Ferguson was back in the Cumberland region and still acting as if at war.

Standing tall, straight, and proud, Ferguson dominates this photograph taken at the request of his guard, the men of the Ninth Michigan Infantry. Courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

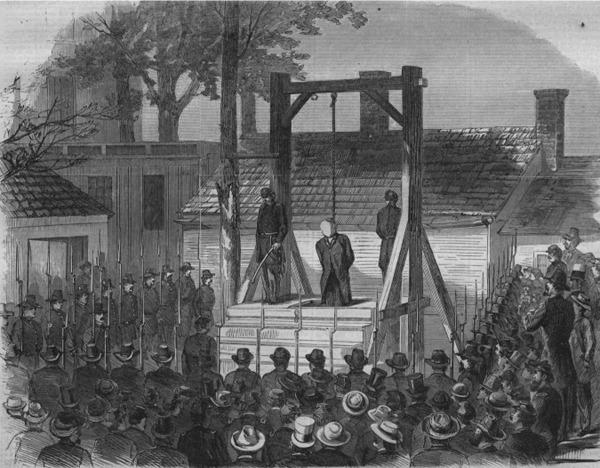

Harper’s Weekly covered Ferguson’s trial and subsequent execution throughout the fall of 1865.

Champ spent the month of April and much of May alternately rebuilding his burned-out house on Calfkiller Creek and hunting for longtime enemies. Toward the end of April, he and another man caught Dave Beatty near Jamestown, Tennessee, but the partisan escaped his captors and received life-threatening wounds.63 Within a few days, Ferguson and several others rode to the Van “Bug” Duvall farm, where the infamous guerrilla killed his last man.64 That same day, Gen. George Thomas authorized his subordinate commanders to publish surrender terms for independent bands in the newspapers.65

While Thomas was offering liberal terms to the mass of Upper Cumberland partisans, Ferguson was an exception to the policy. At the point Thomas ordered the publication of the terms of surrender, Ferguson had already fought his last fight. Therefore, those terms would embrace all participants who agreed to avoid partisan activities from then forward, which Ferguson evidently did. However, when news of Ferguson’s post-Appomattox, but presurrender, attacks reached Thomas, the general made the guerrilla an exception to the rule and refused his surrender under the terms offered to the others. On May 16, Thomas’s subordinate general, Lovell Rousseau, made the decision a matter of public record when he declared: “Champ Ferguson and his gang of cut-throats having refused to surrender are denounced as outlaws, and the military forces of this district will deal with and treat them accordingly.”66

By the end of May, Champ Ferguson had been arrested and remanded to prison in Nashville to await his trial. Beginning on July 3, the proceedings lasted until September 18. During that time, the prosecution had seated dozens of witnesses, while the defense managed only a handful of friendly voices. It took only a few hours for the military commission to arrive at its verdict, and, on October 10, the court announced that Ferguson had been convicted on fifty-three counts of murder and sentenced to hang for his crimes. At 10:00 A.M. on October 20, 1865, Champ Ferguson climbed the steps of the gallows and was executed, thus ending the bloodiest single career of the Civil War.67

This essay is an abridgement of my forthcoming biography of Champ Ferguson.

1. Nashville Dispatch, August 19, 1865; J. A. Brents, The Patriots and Guerillas of East Tennessee and Kentucky (New York: J. A. Brents, 1863; reprint, Danville: Kentucky Jayhawker, 2001), 21–22; J. D. Hale, Champ Furguson: The Border Rebel, and Thief, Robber, and Murderer (Cincinnati: privately printed, 1864), 3–4; Albert R. Hogue, Mark Twain’s Obedstown and Knobs of Tennessee: A History of Jamestown and Fentress County, Tennessee (Jamestown, Tenn.: Cumberland, 1950), 58, and History of Fentress County, Tennessee (Baltimore: Regional, 1975), 35; Thomas Davidson Mays, “Cumberland Blood: Champ Ferguson’s Civil War” (Ph.D. diss., Texas Christian University, 1996), 23; Nashville Daily Press and Times, July 13, 1865.

2. Hambleton Tapp and James C. Klotter, eds., The Union, the Civil War, and John W. Tuttle: A Kentucky Captain’s Account (Frankfort: Kentucky Historical Society, 1980), 1–2; Hogue, Mark Twain’s Obedstown and Knobs of Tennessee, 58; Mays, “Cumberland Blood,” 23.

3. Brents, Patriots and Guerillas, 22; Nashville Daily Press, September 19, 1865; Albert W. Schroeder Jr., “Writings of a Tennessee Unionist,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 9 (September 1950): 250; R. R. Hancock, Hancock’s Diary; or, A History of the Second Tennessee Confederate Cavalry (Nashville: Brandon, 1887), 36–37; Mays, “Cumberland Blood,” 41; L. W Duvall Testimony, August 7, 1865, Proceedings of the Trial of Champ Ferguson, Record Group 153, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Army), 1792–1981, Court Martial Case Files, Textual Archives Services Division, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. (hereafter cited as NARA-Trial); and Alvin C. Piles Testimony, July 26, 1865, NARA-Trial.

4. Esther Ann Frogg Testimony, August 2, 1865, NARA-Trial; Isaac T. Reneau to Gov. A. Johnson, March 31, 1861, Military Governor Andrew Johnson Papers, 1862–1865, Manuscripts and Archives Section, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville (hereafter cited as TS LA-Johns on); Nashville Union, October 21, 1865.

5. P. A. Hale Testimony, August 12, 1865, NARA-Trial.

6. Miss Elizabeth Wood Testimony, August 4, 1865, NARA-Trial; Robert W. Wood Testimony, August 5, 1865, NARA-Trial; Brents, Patriots and Guerillas, 23; Isaac T. Reneau to Gov. A. Johnson, March 31, 1861, TSLA-Johnson; Lucinda Hatfield Statement, n.d., and Rufus Dowdy Statement, n.d., both in J. D. Hale, Sketches of Scenes in the Career of Champ Furguson and His Lieutenant (n.p.: n.p., 1870), 18–19.

7. James W. Orr, Recollections of the War between the States, 1861–1865 (n.p.: n.p., 1909), 13; Bonnie Ball, “Impact of the Civil War upon the Southwestern Corner of Virginia,” Historical Sketches of Southwest Virginia 15 (March 1982): 3; Robert Perry, Jack May’s War: Colonel Andrew Jackson May and the Civil War in Eastern Kentucky, East Tennessee, and Southwest Virginia (Johnson City, Tenn.: Overmountain, 1998), 64; Unknown to W. H. Hays, Esq., May 23, 1865, in “Harlan County Battalion and Reports,” Harlan County Footprints 1, no. 4 (n.d.): 134; and James A. Ramage, Rebel Raider: The Life of General John Hunt Morgan (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1986), 218, 220.

8. Brents, Patriots and Guerillas, 31; and Mays, “Cumberland Blood,” 61.

9. Brents, Patriots and Guerillas, 30; Eastham Tarrant, The Wild Riders of the First Kentucky Cavalry: A History of the Regiment, in the Great War of the Rebellion, 1861–1865 (Lexington, Ky.: Henry Clay Press, 1969), 57; Mays, “Cumberland Blood,” 61, 173–74; Nashville Dispatch, July 21, 1865; Thurman Sensing, Champ Ferguson: Confederate Guerrilla (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1942), 76; David Beatty Testimony, July 20, 1865, NARA-Trial.

10. Brents, Patriots and Guerillas, 12–14; Tarrant, Wild Riders, 21; J. D. Hale, Champ Furguson: A Sketch of the War in East Tennessee Detailing Some of the Leading Spirits of the Rebellion (Cincinnati: privately printed, 1862), and The Border Rebel, 3–4.

11. Winburne W. Goodpasture Testimony, August 22, 1865, NARA-Trial; Undated Statement signed by John J. McDonald, John Boles, Sen., H. Stover, and John Winingham, in Hale, Sketches of Scenes, 7–8; James Beatty Testimony, August 9, 1865, NARA-Trial; Marion Johnson Testimony, August 9, 1865, NARA-Trial; Hale, A Sketch of the War, 8. Goodpasture (Testimony, August 22, 1865) and Rufus Dowdy (Testimony, August 26, 1865, NARA-Trial) confirmed that McHenry broke the accord within days of its adoption. Other interesting statements regarding the compromise effort can be found in Hale, Sketches and Scenes, 7–10; and John A. Capps Testimony, August 21, 1865, NARA-Trial.

12. Jonathan D. Hale to Honorable Andrew Johnson, December 16, 1861, in The Papers of Andrew Johnson, vol. 5, 1861–1862, ed. Leroy P. Graf and Ralph W. Haskins (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1976), 61; Speech to Davidson County Citizens, March 22, 1862, in ibid., 5:237; and Isaac T. Reneau to Gov. A. Johnson, March 31, 1861, in ibid., 5:257–58.

13. Esther A. Jackson Testimony, July 28, 1865, NARA-Trial; Rufus Dowdy Testimony, August 24, 1865, NARA-Trial; A. F. Capps Testimony, August 2, 1865, NARA-Trial; and Brents, Patriots and Guerillas, 25.

14. Schroeder, “Writings of a Tennessee Unionist,” 257.

15. Daily Nashville Union, April 19, 1862.

16. Tarrant, Wild Riders, 76–79.

17. Hogue, History of Fentress County, Tennessee, 35.

18. Basil W. Duke, History of Morgan’s Cavalry (Cincinnati: Miami Printing & Publishing Co., 1867), 165–66; Ramage, Rebel Raider, 85–87; and Richmond Enquirer, May 22, 1862.

19. Basil W. Duke, The Civil War Reminiscences of General Basil W. Duke, C.S.A. (1911; reprint, New York: Cooper Square, 2001), 123–24.

20. Nashville Dispatch, August 25, 26, 1865.

21. R. C. M. to Dr. Johny, May 4, 1863, John Hunt Morgan Papers, Southern Historical Collection, Manuscripts Department, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (hereafter cited as SHC-Morgan).

22. Duke, Reminiscences, 123.

23. John Huff Testimony, August 10, 1865, NARA-Trial.

24. Nashville Union, October 21, 1865.

25. Ramage, Rebel Raider, 137.

26. Ibid.; Grady McWhiney, Braxton Bragg and Confederate Defeat, 2 vols. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1969–1991), 1:341; Duke, History of Morgan’s Cavalry, 325–42; Thomas Lawrence Connelly, Autumn of Glory: The Army of Tennessee, 1863–1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1971), 29.

27. Wartime Diary of John Weatherred, copy held privately by Mr. Jack Masters, Gallatin, Tenn.

28. Moses Huddleston Testimony, July 27, 1865, NARA-Trial; Wartime Diary of John Weatherred.

29. Sarah Dowdy Testimony, July 28, 1865, NARA-Trial; Moses Huddleston Testimony, July 27, 1865, NARA-Trial.

30. Nashville Dispatch, August 19, 1865.

31. Report of Col. George G. Dibrell, August 18, 1865, in U.S. War Department, War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 1861–1865 (hereafter cited as OR) (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), ser. 1, vol. 23, pt. 1, pp. 847–48; Report of Col. Robert H. G. Minty, August 11, 1863, in ibid., ser. 1, vol. 23, pt. 1, pp. 846–47.

32. Report of Col. Thomas J. Harrison, January 14, 1864, in ibid., ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 1, pp. 65–66.

33. Report of Col. William B. Stokes, February 2, 1864, in ibid., ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 1, pp. 162–63.

34. Daniel W. Garrett Testimony, July 22, 1865, NARA-Trial; Isham Richards Testimony, July 22, 1865, NARA-Trial; Captain Rufus Dowdy Testimony, August 24, 1865, NARA-Trial.

35. Confession of Columbus German, July 3, 1866, J. D. Hale Papers, Wright Room Research Library, Historical Society of Cheshire County, Keene, N.H.

36. Report of Col. William B. Stokes, February 24, 1864, in OR, ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 1, p. 416.

37. W. B. Hyder Recollections, Special Collections, Angelo and Jennette Volpe Library and Media Center, Tennessee Technological University, Cookeville, Tennessee (hereafter cited as TTU-Hyder).

38. The Battle of Dug Hill is sometimes called the Battle of the Calfkiller.

39. Betty Jane Dudney, “Civil War in White County, Tennessee, 1861–1865” (M.A. thesis, Tennessee Technological University, 1985), 35–36; Monroe Seals, History of White County, Tennessee (Spartanburg, S.C.: Reprint Co., 1982), 71–72; Lewis A. Lawson, Wheeler’s Last Raid (Greenwood, Fla.: Penkevill, 1986), 248–49.

40. James T. Siburt, “Colonel John M. Hughs: Brigade Commander and Confederate Guerrilla,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 51 (Summer 1992): 90.

41. Report of Col. William B. Stokes, February 24, 1864, in OR, ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 1, p. 416.

42. W. B. Hyder Recollections, TTU-Hyder.

43. Ibid.

44. Nashville Daily Union, March 29, 1864.

45. Nashville Daily Union, March 27, 1864.

46. Nashville Daily Union, April 1, 1864.

47. Nashville Union, October 21, 1865.

48. General Joseph Wheeler Testimony, August 28, 1865, NARA-Trial.

49. George Dallas Mosgrove, Kentucky Cavaliers in Dixie: Reminiscences of a Confederate Cavalryman (Jackson, Tenn.: McCowart-Mercer, 1957; reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), 206.

50. William C. Davis and Meredith L. Swentor, eds., Bluegrass Confederate: The Headquarters Diary of Edward O. Guerrant (Baton Rouge: Louisiana state University Press, 1999), 546–47.

51. Nashville Dispatch, August 2, 1865.

52. Nashville Dispatch, August 2, 1865.

53. William C. Davis, “Massacre at Saltville,” Civil War Times Illustrated, February 1971, 45.

54. Report of Surg. William H. Gardner, October 26, 1864, in OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 554–55.

55. Orange Sells Testimony, August 12, 1865, NARA-Trial.

56. Report of Surg. William H. Gardner, October 26, 1864, in OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 554–55; Milton P. Jarrigan, November 8, 1864, MIAC Endorsements on Letters, Department of East Tennessee, 1862–1864, chap. 8, vol. 357, War Department Collection of Confederate States of America Records, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. (hereafter cited as NARA-MIAC Endorsements).

57. “Dr. Murfree Meets Champ Ferguson,” Rutherford County Historical Society (Winter 1973): 15–19.

58. W. W. Stringfield, “The Champ Ferguson Affair,” Emory and Henry Era 17, no. 6 (May 1914): 300–302; R. N. Price, Holston Methodism: From Its Origin to the Present Time (Nashville: Publishing House of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, 1913), 396–99; Orange Sells Testimony, August 12, 1865, NARATrial; Milton P. Jarrigan, November 8, 1865, NARA-MIAC Endorsements.

59. Milton P. Jarrigan, November 8, 1865, NARA–MIAC Endorsements.

60. Document O, NARA-Trial.

61. Ibid.

62. Joseph Wheeler Testimony, August 28, 1865, NARA-Trial.

63. Nashville Dispatch, July 21, 1865; Mays, “Cumberland Blood,” 173–74; Sensing, Champ Ferguson, 76; David Beatty Testimony, July 20, 1865, NARATrial.

64. L. W. Duvall Testimony, August 7, 1865, NARA-Trial; Martin Hurt Testimony, August 8, 1865, NARA-Trial.

65. Document H, NARA-Trial; Mays, “Cumberland Blood,” 176.

66. H. C. Whittemore to Major-General Milroy, May 16, 1865, in OR, ser. 1, vol. 49, pt. 2, p. 806; Mays, “Cumberland Blood,” 177; New York Herald, May 19, 1865.

67. Your Son Robert Johnson to Dear Father, May 31, 1865, in The Papers of Andrew Johnson, vol. 8, May-August 1865, ed. Paul H. Bergeron (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1989), 155–56; David Beatty Testimony, July 21, 1865, NARA-Trial; Nancy Kogier Testimony, August 5, 1865, NARA-Trial; A. F. Capps Testimony, August 2, 1865, NARA-Trial; John A. Capps Testimony, August 21, 1865, NARA-Trial; Winburn Goodpasture Testimony, August 22, 1865, NARATrial; Nashville Daily Press and Times, September 19, 1865; Nashville Dispatch, October 20, 21, 1865.