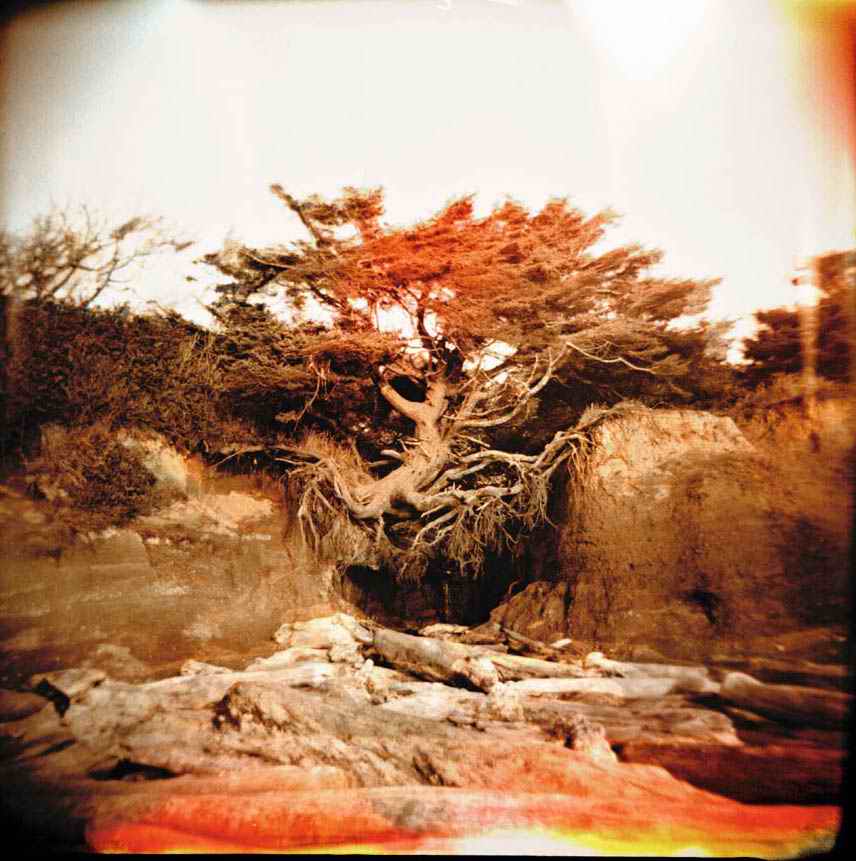

An image taken with a Holga recalls the early days of photography.

iStockphoto.com

From light and composition we move on to the camera and how to get the best out of it. Here are the basics about compacts and DSLRs, settings, exposures and lenses. Plus tips on video performance

Digital, apart from everything else it has done to photography, has complicated hugely the choice of camera – but in the nicest way. From small compacts that will slip into a shirt pocket to high-end SLRs, there is variety to suit most budgets and every need that manufacturers can anticipate, plus a few more features that they hope will become needed.

The ground rules for camera design are open and the nature of digital technology means constant innovation. A year is a generation in the camera world. A large part of the choice of what to buy and what to take when travelling depends on how serious a part of your trip the photography will occupy. But more basic than this is the variety of sensor, of image format, and what still remains the big divide among digital cameras: compact or DSLR.

Digital cameras come in all kinds of sizes and flavours, touting this feature or that, but the two major classes are compacts and DSLR (digital single-lens reflex) cameras. The major difference lies in what the DSLRs have and the others don’t: through-the-lens viewing by means of a prism and a mirror that flips up at the moment of shooting, and interchangeable lenses. Some mirrorless cameras also offer a range of lenses, but by and large, compacts do a simpler job with less fuss and less weight, while DSLRs are the choice of professionals and serious amateurs. This does not mean that DSLR image quality is necessarily better, just that there are more features.

Manufacturers are constantly blurring the lines by launching models designed to “bridge the gap”. The shape of the image (which comes from the shape of the sensor), otherwise known as aspect ratio, tends to divide along the same lines. Most compacts produce images in the proportion 4:3, known as “four-thirds”, while DSLRs tend to follow the old 35mm film standard of 3:2. Creeping up behind is the newer 16:9, which fits HD television, and will probably grow in popularity.

The importance of sensors

Before buying a camera, it is important to know about the variety of sensor. The heart of a digital camera is the product of intense miniaturisation. The front surface is packed with small photosites, one per pixel, which collect photons that are then stored briefly as an electrical charge. The more pixels there are, the higher the resolution of the final image, and so the bigger it can be printed or displayed. For this, sensors and their cameras are rated by megapixels (one million pixels). All digital cameras have sensors that will produce a good-sized print, and will fill a computer or television screen.

To work out how large a digital image you need for a screen or a print, you have to know the resolution, which for a screen is between 72 and 96 pixels per inch, and for most high-quality printing is generally accepted to be 300 pixels per inch.

For instance, a compact camera with a 12-megapixel sensor delivers an image that measures 4000 pixels across by 3000 pixels deep. That will make a good print measuring 13 inches by 10 inches. For a computer display, all you would need to fill, say, a typical 15-inch screen is between 1000 x 600 and 1200 x 800, while even HD television needs just 1920 x 1080. In other words, for almost all needs other than large gallery prints, most camera sensors do the job perfectly well.

iStockphoto.com

The photosites on a sensor collect just light, and do not discriminate colour, so to create a colour image, the sensor is faced with a grid-like transparent filter called the Bayer array in a pattern of red, green and blue. One colour covers one pixel, so the colour resolution is lower than the bright-to-dark resolution, and the “colouring” of the final image is estimated in the camera. However, as our eyes don’t require as much detail in colour as they do in brightness, it all works out well.

Calculating colour is just one of the tasks that the camera’s internal processing has to do. The others are converting the electrical charge from the sensor into digital values, and making the image look “right” to the human eye by brightening part of the range. Digital capture is “linear” in that it doesn’t vary from bright to dark, whereas the human eye, and film incidentally, registers more information in the highlights and shadows.

Processing images inside the camera is a complicated business, which is why sensor and processing unit are inseparable. Sensor sizes and performance vary between cameras, and the best are found in high-end DSLRs, which generally have what are called full-frame sensors (meaning the same size as former 35mm film: 24x36mm). Even modest compacts have 10MP, but while squeezing more and more pixels onto a sensor improves the amount of detail that can be captured, it does not help noise, which is why DSLRs that perform well at high ISO sensitivity settings make more careful use of their larger sensors. Larger pixels capture more light and so are less prone to noise. If you are choosing between cameras, make sure that you check megapixels, colour fidelity and noise performance on one of the many comparative websites.

| Retro Revival |

|---|

Perverse though it may seem to many, the super-technology of digital cameras has bred a reaction – a new-found love among some photographers for the imperfections and distressed-image qualities that came from cheap, throw-away plastic cameras. Models like the Holga and the Diana make a virtue out of low fidelity, utter simplicity, and the effects of using a cheap plastic lens, which include softness, colour fringing, flare and vignetting (darkening towards the corners). This cult is, of course, a part of the constant search among photographers and the people who use photography for new and different styles of imagery. If you are on the road, one extra advantage of toy cameras, if you like their results, is that they are unlikely to get stolen! |

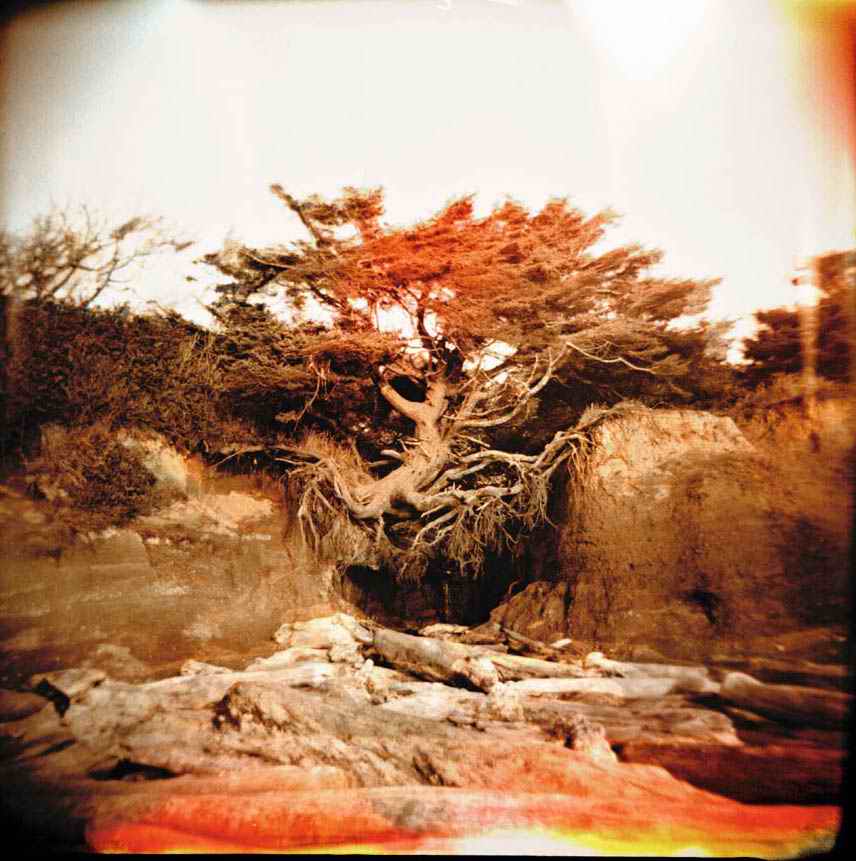

Still with film

Digital may have taken over photography almost completely, but it’s a confident prediction that film will never disappear. Some photographers still prefer film for being less complex and for being more forgiving of harsh lighting and less-than-perfect exposure. Film cameras are much more mechanical than are digital models, which makes them more long-lasting, and there are countless available secondhand. Taking a film camera on your travels can be a less expensive and more robust option, and if you are in remote places without the necessary supply of electricity, a film camera remains useful. But remember that there is no instant review to show you got the exposure and framing right, so accuracy is important. Film cassettes or rolls need care, in particularly keeping them out of heat and bright sunlight and avoiding too many passes through an airport x-ray scanner.

iStockphoto.com

All cameras offer a choice of settings in order to try and satisfy different tastes and ways of working, and the choice can be daunting. Moreover, manufacturers often cloud the issue by offering proprietary extras with fancy names that in reality are just ways of processing the image that you already captured.

To cut through all of this, just remember that there are three key camera controls – aperture, shutter speed and ISO sensitivity – and then there are the digital settings that affect image appearance and quality. First, let’s look at the three key controls, all of which control the amount of light that goes to make the image, but do other things as well.

Abe Nowitz/APA

Aperture

The lens aperture is a diaphragm that closes down (called stopping down) to restrict the amount of light from the scene that will strike the sensor and make the image. The aperture is measured in ƒ stops; these are for convenience, so that each stop smaller than the one before lets through half the amount of light.

Because they are on a log scale, the actual numbers don’t immediately suggest this, and the sequence goes like this, from wide to small: ƒ2 ƒ2.8 ƒ4 ƒ5.6 ƒ8 ƒ11 ƒ16 ƒ22. When the diaphragm is completely open, the aperture of the lens is at its maximum, and many lenses go no wider than ƒ4 or ƒ5.6. Lenses that are wider than this at their maximum, such as ƒ2 or even wider like ƒ1.4, are considerably more expensive to make, and are called fast lenses. At the other end of the scale, some lenses, like long telephotos and macro lenses, stop down to ƒ32 or even more.

Older lenses had a mechanical aperture ring on the barrel that could be turned manually, but nowadays aperture can be altered from controls on the camera body. Stopping down has another important effect apart from reducing the amount of light: it increases the front-to-back sharpness in a scene, known as the depth of field. We’ll look at this in more detail later on, but the more you stop down, the more of the scene will be sharply focused. For many, perhaps most situations, this is ideal, but there are others that we’ll look at later when you might want to concentrate attention on just one sharp subject within the scene.

Kevin Cummins/APA

Sarah Louise Ramsay/APA

Neil Buchan-Grant/APA

With any picture you are about to take, it helps to decide from the start whether you want clear detail throughout, or to make one part of the scene stand out by being sharper than its background and/or foreground. In the first case, the aperture you need will depend on how deep the scene is. Landscapes and cityscapes where you have middle-distance to distance but no foreground – overall views, in other words – will usually be sharp with a middle aperture setting – ƒ8 or ƒ11, for example.

Close-ups with foreground and background both in frame will definitely need a small aperture (eg ƒ22), although at such small apertures the lens sharpness suffers a little. To throw all but one subject out of focus, make sure that it is clearly separated in distance from anything else, and use the widest aperture possible.

Shutter speed

The shutter speed also controls the amount of light that reaches the sensor, so that stopping down the aperture by one ƒstop at the same time as slowing down the shutter speed by one level leaves the exposure unchanged.

The reason for this choice is so that you can decide whether you would rather have good depth of field from a small aperture, or sharply caught movement from a shorter shutter speed. As with depth of field, most people in most situations would prefer to have any movement in the frame, such as someone running or a bird flying, sharp rather than blurred.

But photography allows for all kinds of creative imagination, and some motion blur – a kind of streaking that happens when the shutter speed is slower than the movement – can give a better feeling for action.

Peter Stuckings/APA

It is useful to be aware of two things: the slowest shutter speed at which you can hold the camera without introducing shake into the image, and the shutter speeds needed to freeze different movements of subjects. Your best hand-holding shutter speed can be improved by a few simple techniques, including keeping your hands tucked into your sides, squeezing not jabbing the shutter release, and using a solid grip by letting the camera sit firmly in the palm of one cupped hand.

It will also depend on the focal length of the lens, as the longer the focal length, the more magnified will be any twitches and shakes. As a rule of thumb, 1/125 sec is generally safe (though you would need faster with a long telephoto of more than, say, 300mm), while it’s possible to train yourself to shoot at 1/30 sec or even slower with a wide-angle lens. However, the subject itself may show blur at these lower speeds.

| Motion Blur and Panning |

|---|

When the shutter speed is too slow to freeze movement (either the subject or the camera), the result is streaking in the image – in the direction of the movement. This is motion blur, and whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing depends on the kind of result you have in mind. A perfectly frozen moment at 1/500sec or faster, such as of a horse in mid-gallop with all legs in the air and dust flying, everything crisply captured, is one kind of technical perfection, but controlled motion blur can often convey an impression of speed better than anything else. The blur of spokes on a bicycle shows that the otherwise-sharp cyclist is actually in motion, and if in addition you were to follow the bicycle with the camera, and used a moderate-to-slow shutter speed, such as 1/30sec or 1/60sec, then the background would streak in motion blur while most of the bicycle would stay sharp, which will give an even more impressionistic image of movement. Following a moving subject like this is called panning, and is a very useful technique for helping the moving subject to stand out, in much the same way as a wide aperture helps to keep a subject distinct from its blurry, out-of-focus background. Practise this at different shutter speeds to become familiar with the degree of blur you like best. |

When choosing the right shutter speed for a moving subject, remember that it’s how fast the movement looks through the viewfinder – someone running at a distance, with a wide-angle lens does not need as fast a shutter speed as they would if filling the frame and zipping across it in a second. Three rules of thumb are:

1. 1/60 second when there is only gentle movement

2. 1/125 for a person moving normally

3. 1/500 (at least) for any action that you would generally consider fast, such as action sports.

If a subject is running or moving across your field of vision, the natural reaction is to swing the camera to keep it in the frame; this is known as panning, and of course helps to keep the subject appearing to move slower in the frame. Finally, some cameras now feature tiny micromotors to “stabilise” the view and compensate for shaking hands and other involuntary movements. This vibration reduction, if your camera has it, can help you to photograph at up to two levels of shutter speed slower than you would otherwise be able – such as from 1/60 unaided to 1/15 with.

Richard Nowitz/APA

Chris Stowers/APA

ISO sensitivity and noise

This is the third way of controlling the exposure. Sensors work at their best when they have plenty of light, and the sensitivity of a sensor is measured in units called ISO (which stands for International Organization for Standardization).

ISO 100 to ISO 200 is typical. However, the sensitivity can be boosted from the camera menu by selecting from the choice of higher ISO settings, which is useful if the light levels are low, such as at dusk or indoors, or if you want to keep the shutter speeds fast or the aperture small, or both together. There is, however, a price to pay, and that is the image quality, because the higher the ISO, the more noise there will be in the image. Noise has a grainy, speckled appearance, and detracts from the appearance of a digital photograph.

But how much is acceptable? This depends on personal taste, what compromises you are prepared to make (a noisy image may well be better than no image at all), and how large the image is displayed.

Also, noise is most glaring in featureless parts of a picture that are mid- to dark in tone, like a dusk sky, while if there is a lot of detail in the image, this will make the noise much less noticeable. And all sensors are not equal when it comes to noise. High-end cameras designed for low light or fast action (invaluable in sports and wildlife photography) deliver much less noise at high ISO settings than others – but expensively.

Auto or manual

When it comes to choosing these settings – aperture, shutter speed and ISO – the first consideration is almost always the exposure. In the next section we’ll look at this in more depth. Most cameras will do this either completely automatically, or partially, and in most lighting situations this works perfectly well.

Simple compacts give you little or no choice, but more advanced models allow you to choose between the depth of field from the aperture, the motion-stopping power of the shutter speed, and the image quality from the ISO setting.

Automatic modes that cameras offer therefore tend to be Aperture Priority (you choose the ƒstop and the camera sets the shutter speed), Shutter Priority (you choose the shutter speed and the camera sets the aperture) or a Programmed Mode, which is more sophisticated.

Andy Belcher/APA

Programmed Modes make assumptions about minimum useful shutter speeds and juggle the aperture shutter and ISO to give a kind of best compromise. On more advanced cameras you can tailor the Programmed Mode to your own preference. But also on advanced cameras, strangely enough, you can opt to make all the adjustments manually.

But why would anyone want to do this, given that auto exposure works so seamlessly? One reason is that it is not always easy to remember exactly what the camera is doing with it s particular auto mode, and it might be increasing the depth of field when you might not want it. Another, more basic reason, is that shooting manually helps you think about the camera controls, and they are, in truth, not that complicated. It’s why some people prefer a car with manual gear change.

Focus

Automatic focus is standard on cameras, although some will allow you to focus manually if you want. What continues to change, however, are the different ways in which a camera’s focusing system will decide what to focus on.

The simplest method remains whatever appears in a small central rectangle in the frame, and this suits many subjects. Yet as more people learn to compose photographs in a more interesting way, such as offsetting the main centre of interest, this does not always work.

However, most cameras will lock the focus if you press the shutter release just halfway, so a time-honoured technique is to aim at the subject you want sharp, half-press the release and hold it while quickly re-composing the scene.

But automated focusing gets cleverer, and some cameras make a selling point of recognising faces and then focusing on them. Others let you choose to have the focus continually re-adjust as the subject moves. Some high-end cameras have a setting that, once having focused on a subject, will actually track it wherever it moves in the frame, keeping it sharp – useful for sports and wildlife photography.

Abe Nowitz/APA

This kind of sophistication is useful, as long as you know how it works, but can be a problem if it does what you don’t expect. The only solution is to find out from the manual exactly how your camera handles focus, and if you can choose between methods, decide which is most convenient for you. Often, the old-fashioned ways are the most certain.

Image size, quality, format

Usually, these are settings that you will not often want to change, once you have decided on what suits you best. As we saw under Sensor, the number of megapixels determines the final image size. Large is always good, except for the amount of space it takes up on your memory card, and that is one of the things to think about when choosing which image format to shoot and save in.

Not all cameras offer all three choices, but they are JPEG, TIFF and Raw. JPEG is the most widely used format in the world because it is universally recognised and compresses the image file so that it takes up much less space. It also saves faster to the memory card, which can be useful if you are shooting a lot of images rapidly. There is some theoretical loss of image quality because of the compression, but in practice impossible to see when looking at the image.

TIFF is another format, used especially when working on digital photographs on computers, and is as high quality (uncompressed) as is possible.

| Formats and the advantages of Raw |

|---|

Images can be saved in several sizes and qualities, but an image saved in Raw is much easier to manipulate. As explained above, the industry standard format is a JPEG, which is compressed so that it takes up little space on the memory card. Rather less common (it depends on the camera model) is a TIFF, which is not compressed. In addition, mid-range to high-end cameras allow you to save the raw data captured from the sensor so that you can process it yourself later on a computer; this format is called, not surprisingly, Raw, and most serious photographers save their images this way, because it retains more brightness and colour information. Choosing Raw format in the camera’s menu rather than JPEG or TIFF has advantages that make it the choice of most professionals. It preserves the “raw” unprocessed data that the sensor captures, and this includes extra latitude in the exposure. When you take a picture and then review it on the camera’s LCD screen, what you are seeing is just a quick JPEG interpretation. Hidden beneath this is more data with the potential for better quality, because cameras that have the Raw option capture in a greater bit-depth (12 bit or 14 bit) than the 8 bits used in JPEGs. If you save just in JPEG, you lose this, but in Raw you can often actually recover some exposure when you open the image in software such as Photoshop and Lightroom. Also, any settings that you might have applied, like white balance, sharpening, contrast and so on are kept separate from the Raw data, so that later on the computer you can change these at will and with no quality loss at all. As mentioned, the only disadvantage with Raw is that it is slower for some cameras to save, and takes up more space than a JPEG. Cameras that save in Raw usually offer an extra option of saving a JPEG as well, and if you don’t mind using the small amount of extra space that this needs, it is a useful insurance to have the two versions of the same shot. Because Raw formats are taken directly from the sensor, and because each camera manufacturer has its own way of doing things, they are not standardised. Nikon’s is quite different from Canon, for example. Nevertheless, good processing software can deal with all of them, because shooting in Raw is so popular. |

But it takes up much more space on the memory card than a JPEG, and lacks the processing advantages of Raw. This third format, Raw (not an acronym; it really does mean “raw”), keeps the full image data captured by the sensor, and because of this is the professional choice. It takes up more space than a JPEG, and is slower to save, and each camera manufacturer has its own proprietary formula for creating it, but the quality advantages are considerable.

Memory cards

Images are saved onto whatever memory card you choose to put in the camera. There are different shapes and sizes, such as CompactFlash, SD, miniSD and Memory Stick, but of course any one camera takes just one kind. Where you have a choice is in the size–the storage capacity in other words.

Cards are classified by the number of megabytes (MB) or gigabytes (GB), and because high-capacity cards cost more, it’s worth estimating how much you will be shooting on a trip. Don’t think of storing all your images from the entire trip on the memory card, because this is a more expensive way of storing images than a hard drive, and because you should always make backups of your images, but do think of how many images you will want to capture on, say, a day’s shooting.

As we have seen, the size of the photographs measured in megabytes can vary. But once you have chosen these, you will know from the camera manual how much space they will take on the card. For example, if you elect to shoot and save Raw images with a 10 to 12 megapixel camera, and use the camera’s compression setting, it’s likely that each image will need about 15 MB. So around 60 of these will fit in one GB of a memory card. And memory cards are available in several-to-many GB.

iStockphoto.com

White balance

Humans consider white to be the normal colour of light, but in practice it comes in a range, from the orange of a good sunset to blue in the shade under a clear blue sky. Artificial lighting produce other, sometimes odder, colours, such as greenish from some strip lighting, yellow from sodium streetlights, and a sort of creamy light that seems to drain colours from compact fluorescents (CFLs).

Yet the eye and brain are very good at ignoring these colour shifts because we get used to them after several minutes. Not so the camera sensor, which simply records the exact light and its colour. For this reason, camera menus offer a choice of White Balance settings, generally in a list that contains Sunlight, Cloudy, Shade, Fluorescent, Incandescent, or similar descriptions. The idea is that you choose whichever suits the occasion, so that if, for example, you move into the blue-tinted shade of a building to take a portrait on a bright, clear day, using the same Sunlight setting you had for the previous shot, you will end up with a blueish image. Change to Shade, however, and the camera will add a warmer overall tone.

Corrie Wingate/APA

If you choose Auto, the camera will just do the best it can to give an overall neutral cast. Even if you forget to change this when you should, or simply make a mistake, the result can be corrected later on the computer. And if you shoot Raw, it doesn’t matter at all what White Balance setting you choose, as the Raw box explains.

Style settings

Beyond the really important settings just described, there are others which vary from one camera manufacturer to another. These make processing changes to the image to give it more or less contrast, to sharpen it, make it more or less colourful, even pull out details from shadows.

These are all settings that affect the style of the image, and are specific to each camera model. This may seem on the face of it an excellent idea, to give more oomph to one image or more pastel subtlety to another at the time you shoot them, but it is as well to know what is really going on inside the camera.

All of these special style settings are ways of processing the image after capture, and if you have chosen to save the image as a JPEG or TIFF, it really means that the camera’s processor is throwing away image information. If you shoot Raw you are protected from this, but in any case, everything than a camera’s built-in processor can do, a computer running an image program can do better. Unless you really cannot be bothered with tweaking your images when you get home, think twice about accepting the camera’s kind offer to process your images on the spot.

The number one concern among all photographers is getting the exposure right. In principle, it could hardly be simpler: all cameras have built-in meters to judge the brightness and then, usually automated, the aperture and shutter speed are set to allow just the right quantity of light to strike the sensor. Raising the ISO sensitivity is a third option if the light levels are too low.

And yet, with all this help, exposures still sometimes go wrong – some part of the picture is too bright or too dark. There are three reasons. One is that digital sensors capture light in a way different from our own eyes (or film, for that matter), and this can cause special problems in the highlights.

A second reason is that certain lighting conditions are challenging, particularly shooting into the light and when there is very high contrast. The third reason is more personal – only you can decide which part of the scene is the most important and needs the exposure to be right for it. Cameras are good at measuring light, but not at deciding priorities.

Dynamic range

This is the range of brightness, from deepest shadow to brightest highlight, and can be measured in different ways, but the easiest for photography is in fstops. An average landscape scene in normal sunlight – not harsh and not into the sun – has a dynamic range of about 9–10 stops. A landscape on a cloudy day that does not include the sky could a range of about 4–6 stops.

These conditions are fine for a digital camera, because the dynamic range of sensors varies from about 10 stops (cheaper cameras) to about 12–13 stops (high-end DSLRs). Exposure problems set in, however, with very contrasty sunlit scenes (crisp air without haze) and when you photograph into the light, when the dynamic range can be in the order of 14 stops to 16 stops. In these conditions, an average exposure will give too-dark shadows or over-exposed highlights, or both together. This doesn’t mean that the image is “wrong”, just that you have to give up detail in the shadows, highlights or both.

Emma Gregg/APA

Take care of the hIghlights

Our eyes are remarkably good at seeing a wide range of brightness, and one reason is that we are not as sensitive to really bright tones as we are to mid-range tones.

A camera sensor has no such built-in compensation; its photosites, like miniature wells, just fill up with photons at the same rate, and when each one is full the result is pure white. So when an area of the view is recorded on the sensor as white, it has no detail whatsoever. Moreover, instead of gently shading to white, an over-exposed digital image just goes to white with a sharp break.

Imagine photographing a scene which has the sun in view. With a normal exposure, the sun will of course go white, which is expected, but in the area of sky close to it there is likely to be a sharp break.

Modern processing software is quite good at repairing this kind of defect, but it is always best to protect the highlights, and this means adjusting the exposure a little darker than usual. Processing software is better at recovering shadow detail than it is at restoring highlights.

Exposure compensation

When the camera’s metering doesn’t get the exposure quite right (and for the kinds of lighting situation when this may happen, almost all cameras allow you to raise or lower the exposure by up to 2 ƒstops, and usually in steps of a third or a half a stop. The actual control varies from camera to camera, but use it if the preview of the shot you just took appears too dark or too light.

| Histogram and clipping warning |

|---|

Better models of digital camera offer two valuable aids when they play back a photograph that you just took on their LCD screen. One is a histogram, the other is a warning about any over-exposed areas in the picture. A histogram is a solid graph that shows how the tones in an image are distributed, from dark to light. If the image is well-exposed, without loss of shadow or highlight detail, the histogram will look like a peak or set of peaks centred in the graph. If the picture is a little under-exposed, the peak will be shifted to the left, and if a little over-exposed, as in this example, it will be shifted to the right. If the over-exposure is serious and the highlights are blown out to white, the histogram will be squashed up against the right edge (and the opposite way if greatly under-exposed). If you have the option to turn this histogram on in the camera menu, it is a good, quick check – and with experience you quickly become familiar with the way it should look. The second aid is a “highlight clipping” warning. There may be areas of an image that fall outside the maximum intensity that can be represented. These over-exposed areas will turn to white, and typically flash when the mode is selected. A glance will tell you when you have a problem, and give you the chance to adjust the exposure to compensate, and shoot again. |

When to change the ISO

Changing the sensitivity of the sensor is a very digital solution to exposure, vastly more convenient than changing to a faster film. But as we saw above,the penalty is a more noisy image, so as a general rule it’s better to adjust exposure as much as possible with the aperture and shutter speed before turning to the ISO.

Nevertheless, as there are no rules about how much noise is noticeable or acceptable, and as the noise performance of cameras varies from model to model, a sensible approach is to make a test at home. Take any scene that contains some large, smooth and not too bright areas (such as a room with some plain wall space), and photograph the same view at different ISO settings.

Look at the pictures on a computer screen at the size you would normally use them and decide what your tolerance for the noise is, and under what conditions you would compromise. If you usually make prints, have two or three printed the same size. You need do this only once, ideally before a trip.

Neil Buchan-Grant/APA

iStockphoto.com

Britta Jaschinski/APA

Kevin Cummins/APA

Peter Stuckings/APA

Pete Bennett/APA

Bracketing exposures

When in doubt, shoot the same scene at different exposures, from darker to lighter. This is called bracketing, and some cameras have a bracketing mode that you can set, then the camera shoots a burst as you hold down the shutter release.

This is extremely convenient, and it means that you can later delete whatever you don’t want. And there is a new digital reason for doing this, which is different from simply later choosing the exposure you like best. This is the possibility of combining all of these different exposures into a single image that takes the best exposure from each of them.

There are two kinds of ways to do this during processing. The first is exposure blending in which several exposures are turned into a single ordinary image that combines the highlights from the darker exposures and the shadow detail from the lighter exposures. The second is HDR (high dynamic range), which is an un-viewable image file that contains a massive dynamic range, and which then has to be converted into a normal, viewable image.

Tim Thompson/APA

It’s useful to know about these at the time of shooting, because bracket ing exposures is a way of archiving the light – capturing all the details which you can later retrieve on the computer. It takes time and effort, but some views may be worth the trouble.

Although a tripod is ideal, the software is smart enough these days to be able to align hand-held images provided that they are fairly similar. Noticeable movement, such as people walking about, is less easy to deal with, and this technique is really best for static scenes such as buildings or landscapes.

Time exposures

Even when you reach the lowest limit of shutter speed at which you can hold the camera steady, and when you cannot freeze the subject movement, there are still some exciting images to be made, as long as you can fix the camera steady for a few seconds or longer.

A tripod is more or less essential for this. Think of setting up a shot looking into crashing waves, or a waterfall, or with clouds scudding fast across the sky. If you set the shutter speed to several seconds (and the lens aperture smaller to compensate), the result can be quite ethereal (see Motion Blur and Panning).

Dusk and semi-darkness are ideal times, because they will allow the shutter to stay open for minutes, or even hours in the case of a night-sky exposure that reveals the constellations circling around the sky. You would definitely want to save in Raw format for this kind of shot, in order to make adjustment to brightness and colour later.

Fill flash

Some cameras not only have built-in flash, but are programmed to use it whenever the scene is judged to need it. A common case is when shooting against the light and when you want to see detail in the subject, such as a portrait, rather than let it become a silhouette.

A touch of flash fills these shadows without drowning the natural lighting effects. Decide whether you actually like this effect – some photographers prefer to keep the images natural.

Abe Nowitz/APA

While many people struggle to get to grips with the plethora of digital features in a camera, and investigate mega-pixels and formats, the real work in any camera is done by the lens. Compact cameras mainly come with lens attached, DSLRs have interchangeable lenses, but in either case, your initial choice should consider lens quality, performance and focal length.

What focal length means

The defining characteristic of a lens is its focal length, because this is what determines its magnification and the angle of view that it covers.

A “standard” or “normal” focal length is the one at which the view through the camera is more or less similar to the eye’s view, and one very easy way to compare the two is to keep both eyes open when you look through the viewfinder (for those digital cameras). If the subject appears about the same size in each eye, then you have a standard focal length. As most lenses these days are zooms, this is one way of finding out which zoom setting gives the most normal view.

Focal length is measured in milli-metres, and in the days when most cameras were 35mm, lenses were easy to compare in this respect. However, what counts as “standard” actually depends on the sensor size, and there is a variety of sizes. The better DSLRs have full-frame, which means the same as old 35mm, but others are smaller. The general rule is that when the focal length of the lens is the same as the diagonal measurement across the image, it looks “standard”.

So, with full-frame cameras, and like the old 35mm ones, standard is between 35mm and 50mm; anything shorter is wide-angle and anything longer is telephoto. Two things make this important. One is how much of the scene in front of you will be captured, from wide at one end of the zoom range, for example, to narrow at the other end. The other is less easy to quantify but possibly even more important – the character of the image.

Wide-angle photographs have an expansive feeling when used to take in a sweeping view, and an involved, in-your-face feeling when used close to events and people, with a characteristic distortion of shapes at the edges of the frame. Telephoto images magnify and compress the sense of perspective, which can be graphically strong in an opposite way from wide-angle distortion, and they also can give a somewhat cooler, more objective feeling, “across-the-street” rather than close and personal.

Below are a series of shots showing different focal lengths, starting with wideangles.

Depth of field

As we saw under Aperture, stopping down not only lets less light through the lens, it also increases the depth of field, so that front-to-back more of the scene appears sharp. A wide aperture focuses on just a narrow plane, leaving the background and foreground out of focus, and this, often called selective focus, is good for making some subjects stand out from cluttered surroundings.

With a fast lens, the depth of field is even shallower. Telephoto lenses appear to give a shallower depth of field than wide-angles simply because they magnify a smaller part of the scene. This is splitting hairs, but generally and in practice, wide-angle images tend to show more front-to-back sharpness than do telephotos.

Lens speed

Speed in this sense, when talking about lenses, means how much light the lens can capture when it is at full aperture – wide open, in other words.

For photographers who don’t want to compromise on either shutter speed or ISO sensitivity (that is, shoot at as fast a speed as possible and without noise), a fast lens is worth the considerably extra cost.

Lenses are designated by their maximum aperture. Thus, an ƒ2.8 lens is reasonably fast, whereas an ƒ5.6 lens is quite slow – and that is one way that manufacturers can offer relatively inexpensive lenses. Truly fast lenses are specialised and very expensive, and have maximum apertures of ƒ1.4 or ƒ1.2. Longer focal lengths are especially difficult to make fast, and need a lot of glass, which is why the lenses that wildlife photographers prefer, such as an ƒ4 600mm, weighing several kilos, are the most expensive of all.

Chris Stowers/APA

Choosing the right lens

Most lenses these days are zoom lenses, but the range covered varies. They vary in how wide a range they cover, and in whether that range is concentrated around the standard focal length, or in the wide range, or in the telephoto range. In the last two cases, the lenses are usually called wide-angle zooms and telephoto zooms respectively.

With a fixed-lens camera, the choice is just as it comes, but if you are buying a new camera, it is important to compare. With DSLRs, lenses are interchangeable, so the choice is greater, and there is every reason to consider two or three lenses, depending on your budget and how much weight you are prepared to carry. Also, the range of lenses for the principal makes of DSLR include fixed-focal length lenses (known as primes), and specialist lenses such as macro and shift. The argument for prime lenses is that they deliver better optical quality, although good zoom lenses these days are very good and the difference in result not so easy to see. In any case, whether or not your choice is limited, the criteria to think about are first, focal length, and second, quality and lens speed.

Standard lens

The majority of zoom lenses have their range organised round the standard focal length described above. This is the focal length to use when the scene in front of you looks fine just as it is, and needs no assistance from a wider coverage or a greater magnification.

Now obviously the human eye images differently from a camera lens, not least because there is no rectangular frame. Our field of view, if you think about how far to the side you can make things out, just shaded from sharp in the middle to indistinct at the edges.

Andy Belcher/APA

Nevertheless, what you see in front of you, a standard lens will reproduce fairly well, just adding a rectangular crop around it, and its field of view is around 40°.

The character of a standard focal length image is best defined by what it is not: it lacks the distortion and drama from a wide-angle, and it lacks the compression of a telephoto. Some photographers consider it more “pure” in this respect. The viewer is not distracted by any of the strong graphic optical qualities that are possible with the far ends of the range of focal length, and events in the frame can better speak for themselves.

Wide-angle for immersion

Having said that about the standard focal length, visual excitement is addictive, and one way to help this along is to use a short focal length with a wide field of view. “Wide” means between about 50° and 70°, while up to 100° is ultra-wide.

The most basic use for a wide angle is to cover more of the scene in front of you, especially useful if you can’t or don’t have time to move further back. So, good for sweeping landscapes and good for interiors.

In order to get this wide field of view, these focal lengths distort the shapes of subjects away from the centre, and while this might look awkward with something recogniseable like a face, it is by no means always a bad thing. Geometrical distortion adds graphic drama by stretching things near the corners.

Telephotos for distance

Go to the other end of the zoom range, or fit a real telephoto lens, and the angle of view narrows. Medium telephotos cover typically between about 10° and 25°, the really long ones that are ideal for much wildlife photography less than about 6°. However, whereas the angle of view is what tends to be most important for wide-angles, in the case of telephotos it is the degree of magnification that gets most attention.

Chris Bradley/APA

This is easy to work out: simply divide the focal length of the telephoto by whatever is standard. So, assuming 50mm as normal for a full-frame DSLR, a 300mm lens will magnify the view by 6x. This is the basic task for a telephoto – getting closer without moving closer. But in addition, there is a graphically powerful effect of appearing to compress the scene.

Subjects get to be a little closer to their real size in relation to one another. If you stand close to a house with a mountain range as a backdrop and use a wide-angle lens, the house will loom much larger than the mountains, but if instead you walk back and use a telephoto, the mountains will appear more like their impressive size behind the house. This compressing effect can be compelling with the right choice of subject, such as the succession of cliffs and buttes along the Grand Canyon stacked into planes, or pagoda behind pagoda at Bagan, Myanmar.

Close-up and macro

A specialist kind of lens, or sometimes a function built in to regular lenses, is one that will focus very closely to give strongly magnified views of such small subjects as flowers and insects, and in wilderness travel photography they can add to your coverage of the trip.

True macro lenses have their optics optimised for close distances, and will stop down very small, such as to ƒ32, to keep the depth of field deep. Technically speaking, macro means that the image is close to the actual size of the object.

Depth of field is shallow at such distances, but there are digital ways of dealing with this, as described in focus blending.

Panoramas

There have always been specialist cameras to take such wide views, including disposable cameras. But now, with digital, they are hardly necessary, as one of the simplest and most effective tricks in photography, particularly travel photography, is to create a panorama from a sequence of overlapping images.

This is so popular that manufacturers have perfected software to make this happen, and even camera features that aid the process.

Martyn Goddard/APA

Even though the technologies of video and still digital are converging, particularly in DSLRs that are video-capable, as ways of expression they are poles apart.

Still photography is about skillfully catching slices from the motion of life –telling moments that encapsulate a situation in a single shot. Video is about the flow of movement and events, and tells a story in a narrative way. You can, if you are lucky and adroit, catch an evocative still moment from an otherwise unpromising situation, but video more realistically records the entire event.

Nevertheless, one of the exciting possibilities is to mix still and video in a slideshow or movie, and they can fit well together, moving from video to well-caught single moments in stills. For this reason, adding video to your armoury of story-telling can be effective in recording the experiences of travel.

If you’re going to be shooting video, the first thing to decide is what to use. The technological development that allows a still digital camera to record video is hugely popular, but if this is an extra incentive for choosing this kind of camera, you should still consider the conventional alternative of buying a camcorder.

Camera or camcorder

There are pros and cons to either route. The arguments in favour of a video-capable still camera are: it sticks to one system; there is less to carry around and no extra cost; with a DSLR you can take full advantage of its range of lenses, especially wide-angle which camcorders often lack; camcorders have a hard time in low light.

The arguments in favour of a camcorder are: at the moment camcorders generally have better video quality, better audio quality, longer telephoto capability and are ergonomically better for filming; they are also tiny and not particularly expensive. That said, technology moves fast in all these areas, and video-capable still cameras will improve. But then so will camcorders.

Martyn Goddard/APA

Controlling movement

Camcorders are designed ergonomically to be held in the hand. This, plus the fact that it’s fun to walk around with one while filming, suggests that moving the camera is a good idea. Sometimes it is, but more often the result is jerky and incoherent.

The baseline for professional video is the same as for film: slow, smooth movements that are easy on the eye and plenty of footage where the camera is not moving at all. After all, most of the time you will have moving subjects, and this will often be quite sufficient.

Camera movements have their place, but on television and in the cinema they are usually with a purpose. Movements that are obviously handheld are used professionally to give a sense of urgency, and so not at all frequently.

First, practise moving the camera gently and steadily. The easiest and smoothest way of doing this is to use a tripod. Simply loosen the head and grasp the camera with both hands, making sure that any image stabiliser is switched off (otherwise it will actually introduce small movements at the beginning and end of the move).

Start a panning move as slowly as possible, speeding up gently, and at the end, slow down. Leave a few seconds footage at the start and at the end.

Another tip is to plan the move whenever possible, possibly even making a quick dry run first, because to be really successful, a camera move should start with a good composition and end with the same. Use your still photography skills to find these good framings (see Composition).

Also, be sparing with the zoom. Many people believe that because a camcorder has a motorised zoom, it ought to be used a lot during filming. In fact, unless performed very slowly, and very, very occasionally, zoom shots can be tiresome to watch. Use the zoom in the way you would with a still camera: just to select the focal length.

One kind of camera movement that does work well much of the time is from most kinds of vehicle, especially looking forward. The trick is to keep the camera as steady as possible on the vehicle, and here again, a tripod can be invaluable. Imagine being on the Keralan backwaters or on the Mekong River in Vietnam being rowed or poled along by a boatman: simply fix the camera on the tripod at the front of the boat and let the boat’s motion do the rest – or aim it back to the boatman to give some action as well.

Rebecca Erol/APA

Static shots

One of the things that video does best is to capture the movement in the scene. While it may not sound exciting, locking the camera so that it does not move at all is a guaranteed formula for professional-looking results.

Spend time instead on making an effective composition, ideally one that includes moving subjects. A telephoto view down the length of a busy street might not work as a still shot – too many obstructions, the field of view out of focus – but as a minute of video you could be surprised as to how watchable it is.

Movement across the wide HD frame works particularly well, and if this movement starts outside the frame, entering it while the camera is running, so much the better. For instance, imagine a horse-drawn carriage in an old city centre turning the corner. You can see where it is going, so if you frame the shot ahead of it and hold the camera steady, the result will be professional anticipation; the audience will be pleasantly surprised as the horse clops into the frame.

Or another example might be street dancers performing in a town square: fix the camera so that the shot begins empty and a dancer twirls into frame. The possibilities are endless, but the principle is to make full use of whatever movement is going on.

Thinking in sequence

Video automatically tells a tale. Things happen, have a sequence, start somewhere and end somewhere. Very similar to travel, in a way.

To make the most of this, it helps to think like a scriptwriter, but on the spot, imagining how shots will fit together. In still photography, the aim is often simply to find great shots, in whatever order they come, but video needs sequence.

Peter Stuckings/APA

This means, even as you film a compelling scene, think ahead to what should accompany it. This includes setting the scene, which makes establishing shots of the location, even if not particularly exciting, valuable.

Also, think about filming the same scene from different angles and with different focal lengths, so that you can later cut them together. A close portrait of a trader in a market will make more sense if you have a starting shot of the overall market, then possibly a medium shot of the trader’s stall. You can shoot this backwards, in the sense that once you have a great shot, step back and sideways to fill in the gaps.

Talking movies

And as this is likely to be a travelogue, you can have linking dialogue. Some of this can be recorded later as a voice-over, but think how useful it would be to have you in shot talking to camera: “Here I am in…” To do this, consider buying a small microphone that clips onto your shirt, blouse or jacket, with a long lead. And this is yet another argument for a tripod, because “talking-head” shots usually look best when the camera is still, and you can also film yourself without help from a companion.

Easy on the special effects

Just as still digital cameras are increasingly loaded with style settings that process the image to look as you think you want it straight out of the camera (see Settings), so camcorders come with such special video effects as fades and wipes.

For the same reasons that you should think twice about taking this option with a still camera – such effects are irreversible – it may be better to film in a straight and uncomplicated way and leave the transitions and so on until you edit the footage later at home on the computer. More work, yes, but using video at all involves a commitment to doing extensive post-production later. There is a variety of excellent software available for this.

| Software Solutions |

|---|

When it comes to editing your captured video, a number of software options are available. Most computer operating systems come with video editors preinstalled, notably Movie Maker for Windows and iMovie for Mac. These are perfectly adequate for basic video editing. Both feature a large choice of video transitions as well as captioning and audio tools. They are simple to use and you will be able to create great videos in minutes. Both of the aforementioned also include tools for sharing video with families and friends. For a bit more control over your video there is a lot of mid- to high-end software available, including Adobe Premier and Final Cut Studio. These are used by professionals and have a huge range of features which can be incredibly rewarding – if you have the time to learn how to use them. |