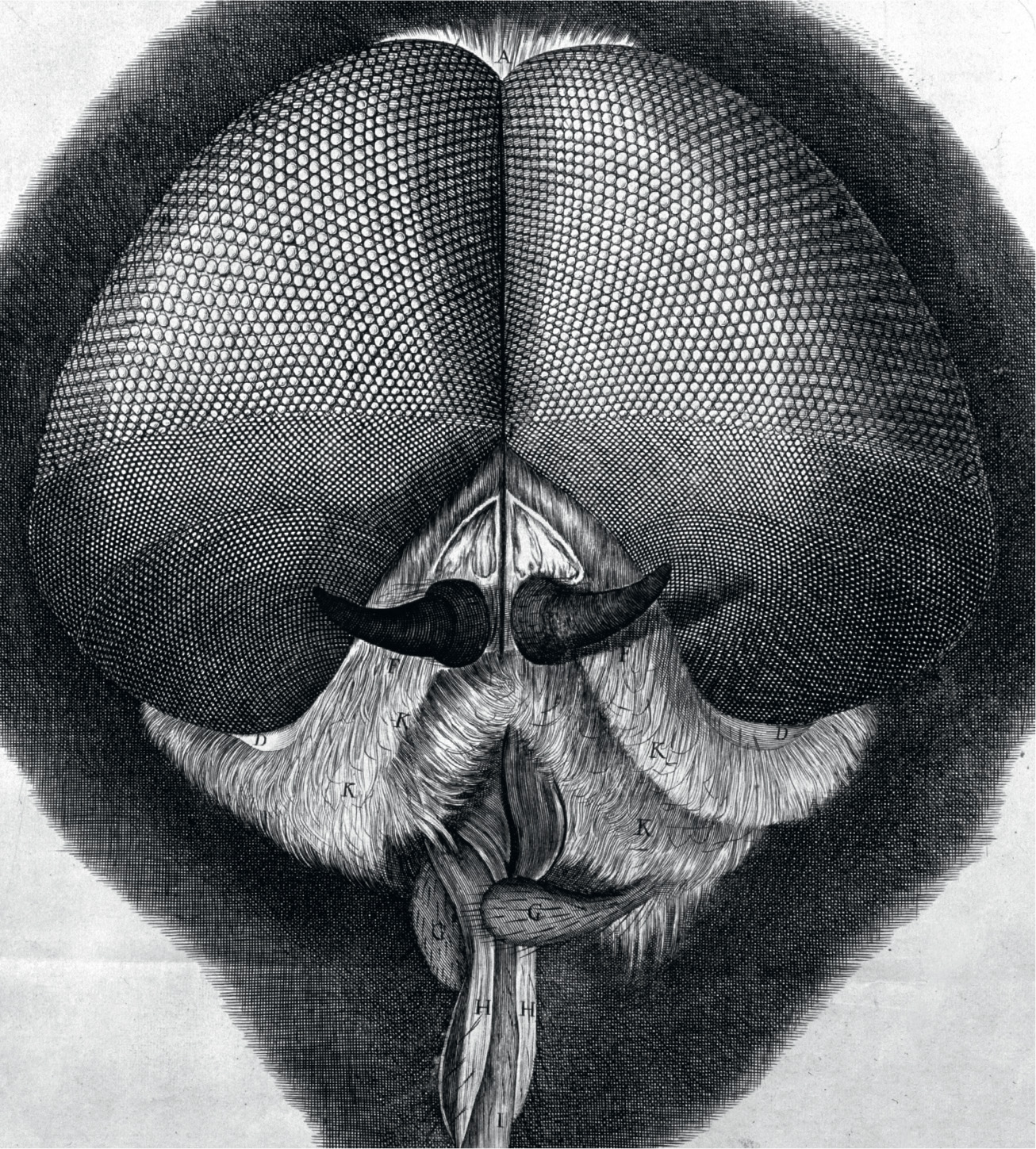

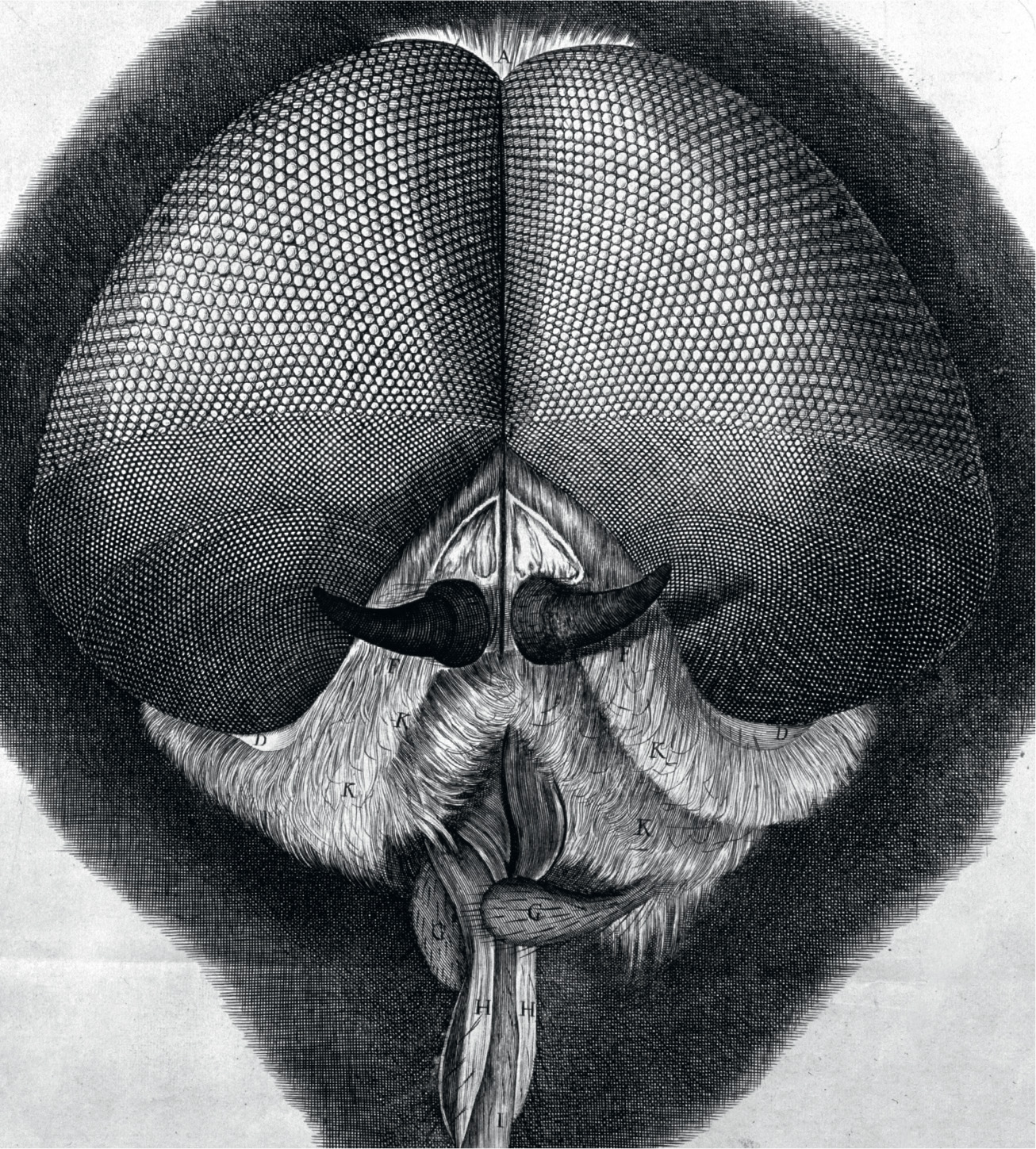

Drawing of the head of a fly, from Micrographia.

Robert Hooke may have missed out on getting his name attached to ‘Boyle’s’ Law, but he soon achieved an even greater experimental success as a pioneer of the use of the microscope. In the second half of the seventeenth century other experimenters also studied the world of the very small using lenses to magnify tiny objects, but it was Hooke who did the most thorough job, and explained his discoveries in a book, Micrographia, which was published in 1665. It was written in English, unusually for the time (most learned tomes were written in Latin), and easy for any educated person to understand. Samuel Pepys called it ‘the most ingenious book that ever I read in my life’.

There were actually two ways to achieve the kind of magnification needed to make microscopy worthwhile. One was pioneered by Hooke’s contemporary, the Dutch draper and amateur scientist, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek. His ‘microscopes’ were single tiny lenses, some no bigger than a pinhead, mounted in strips of metal. They had to be held very close to the eye, and acted as powerful magnifying glasses – so powerful that they could enlarge images 200 or 300 times. These were very difficult to work with, but van Leeuwenhoek made many important discoveries, including tiny living creatures in droplets of water. Hooke used this kind of lens when he needed to pick out the tiniest details in the objects he studied, but he also used a different experimental setup, the forerunner of modern microscopes. These microscopes were made from combinations of lenses, mounted in tubes 6 or 7 inches long (approximately 15–18 centimetres), similar to the way in which telescopes are made. They were easier to work with, but did not give such powerful magnification as the tiny single lenses.

But ‘easier’ does not mean ‘easy’. Anyone who has used a microscope knows that it is important to have a bright light shining on the object being studied at the focus of the instrument. But there was no electric light (or even gaslight) in the 1660s. Candles were not bright enough to do the job. So Hooke used an ingenious arrangement of glass lenses and round containers filled with water to act as spherical lenses to focus light from the Sun (or sometimes a candle) on the object of interest. This worked well for inanimate objects. But he also wanted to study living things, such as ants. These would soon crawl out of the focus of the microscope, but if he killed them then their bodies shrivelled up. He tried sticking them down with wax or glue, but they still wriggled about too much to be studied. Then he hit on the idea of dosing them with brandy to make them unconscious. The ant, he said, was soon ‘dead drunk, so that he became moveless’.

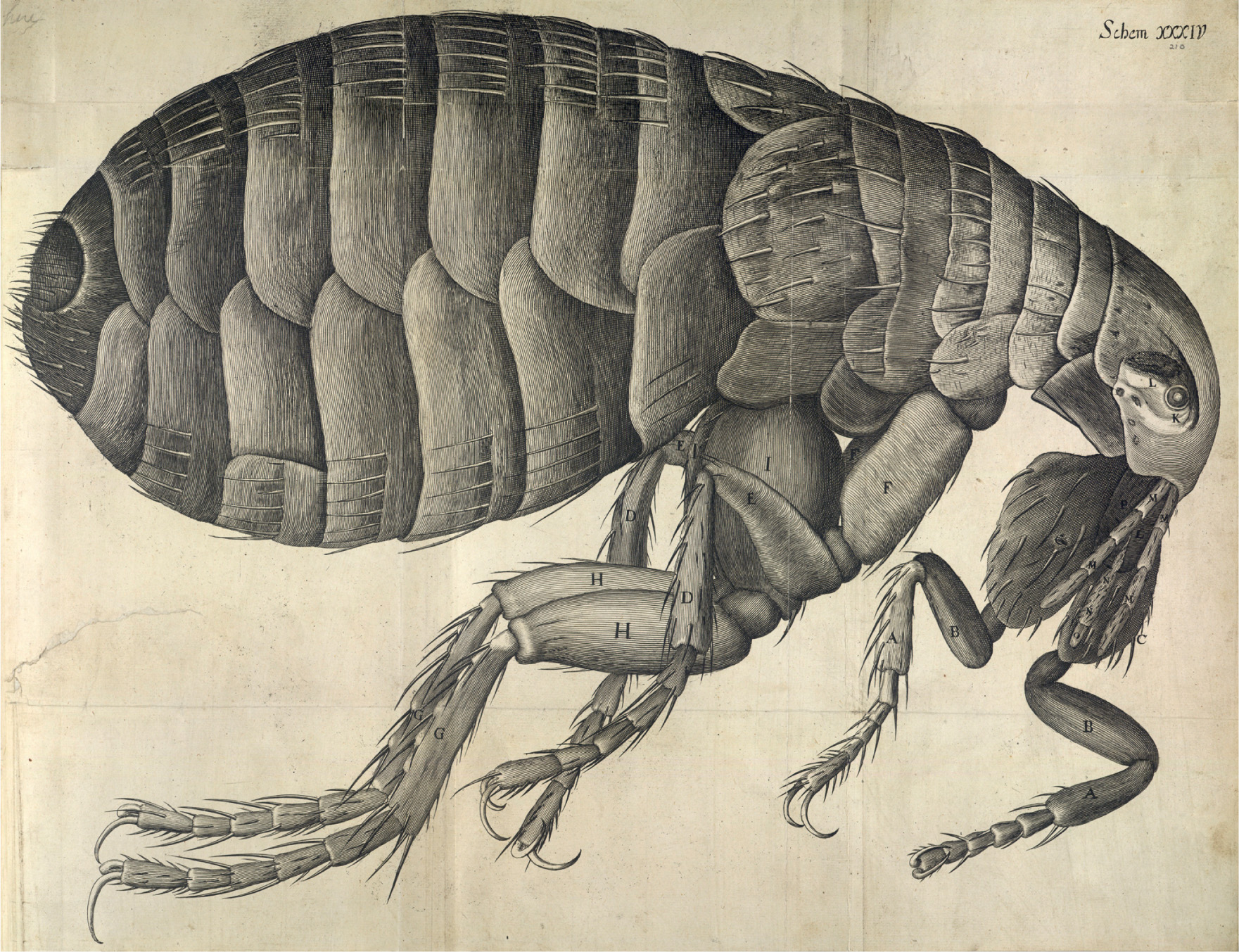

Of course, there was no way to photograph the objects under the microscope, and Hooke’s book is full of beautiful, detailed drawings of what he saw. A seventeenth-century experimenter had to be an artist as well as a scientist. Hooke showed his readers how much irregularity there is in something as seemingly perfect as the point of a needle or the edge of a razor, and he also showed them how much regularity there is in crystals. This, he said, must result from a regular arrangement of the particles making up crystals – an early hint at the existence of atoms.

But perhaps his most spectacular realization was that fossils are the remains of once-living creatures. In the middle of the seventeenth century, it was widely accepted that these peculiar stones, resembling living things, are just pieces of rock that have been distorted by some unknown process to look like living things. But Hooke, with the evidence of his microscopic studies in front of him, said that fossils are not simply contorted pieces of rock. The details matched the patterns of living things too precisely for that to be true. He said that the fossils we now call ammonites must be ‘the shells of certain Shellfishes, which, either by some Deluge, Inundation, earthquake, or some such other means, came to be thrown to that place, and there to be filled with some kind of mud or clay, or petrifying water’. And he realized that because such remains are now found far from the sea, there must have been major changes to the Earth in the past. The reference to a ‘Deluge’ seems to have been a sop to those who believed in the literal truth of the story of the Biblical Flood. Hooke made his own views clear in a lecture at Gresham College in London, where he said that ‘parts which have been sea are now land’, and ‘mountains have been turned into plains, and plains into mountains, and the like.’ A profound inference to draw from looking at tiny objects through a microscope.