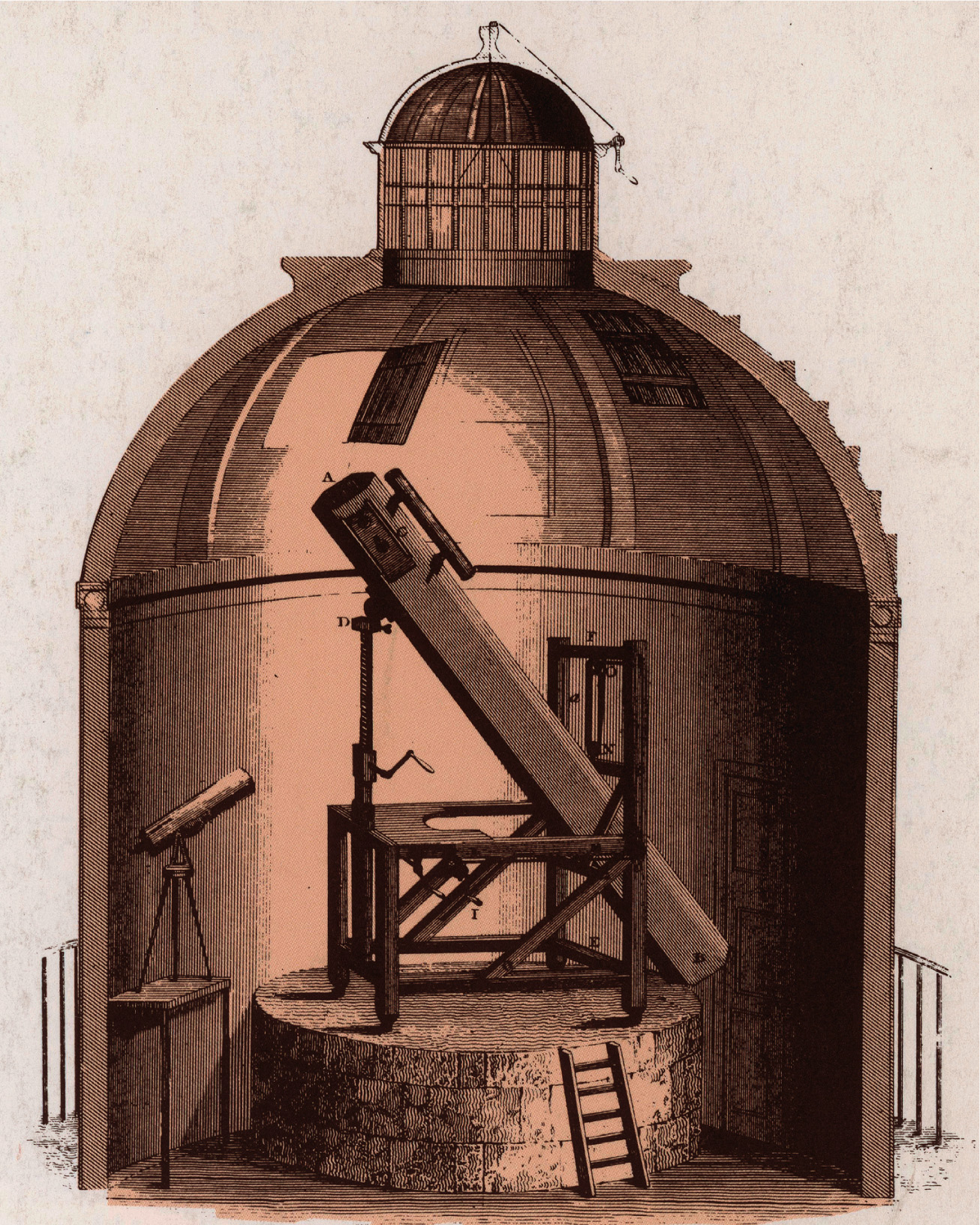

William Herschel discovered Uranus in 1781 with this telescope.

The scientific sensation of the 1780s was the discovery of a ‘new’ planet in the Solar System. This transformed the view of the heavens that had held since ancient times, and began the process of opening up astronomers’ images – of, first, the Solar System, and then of the whole Universe.

The Ancients had observed five planets in the sky, named after Roman gods – Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. By the 1780s, it was known that these planets orbit the Sun, with Mercury closest to the Sun and Saturn furthest out, and Earth was also known to be a planet, orbiting the Sun between Venus and Mars. Of course, the planet discovered in 1781, now know as Uranus, was not really new. It had been around for as long as the other planets, orbiting even further out than Saturn, and had even been observed many times, but it had been mistaken for a star or a comet. It is possible that one of the ‘stars’ identified by Hipparchos in his star catalogue in the second century BC was actually Uranus, although the planet is extremely difficult to spot with the naked eye. Telescopes made it easier to spot, and it is now certain that the planet was identified as a star by John Flamsteed in 1690. A French astronomer, Pierre Lemonnier, observed Uranus several times between 1750 and 1769, without realizing its true nature.

The reason for those missed opportunities, even after the advent of the telescope, is that Uranus is so far from the Sun that it moves very slowly across the sky as seen from Earth. The other planets, as well as being brighter and easier to see, move noticeably against the background stars, which gives them their name, from the Greek word for a ‘wanderer’. But this also highlights the importance of applying the ‘experimental’ method to observations as well as to experiments. It is no good looking at the night sky casually from time to time and speculating about what you see. You have to make methodical observations over a long period of time, keeping careful records and comparing observations from different times to work out what is going on.

That is exactly what William Herschel, assisted by his sister Caroline, was doing in the early 1780s. Herschel was a successful musician, living in Bath, who had developed a passion for astronomy and built his own telescopes, observing the skies from the garden of the house he shared with Caroline. He was actually carrying out a methodical search for double stars when, on 13 March 1781, he noticed an object that appeared in his telescope as a tiny disc, rather than a star-like point of light. (Stars do not appear as discs even in the best telescopes because they are so much further away than planets.) On 17 March, he looked for the object again, and found that it had moved against the background stars. The natural assumption was that he had found a comet, and he reported the discovery as such to the Royal Society. But when Herschel sent details of his discovery to the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, Maskelyne replied: ‘I don’t know what to call it. It is as likely to be a regular planet moving in an orbit nearly circular to the sun as a Comet moving in a very eccentric ellipsis. I have not yet seen any coma or tail to it.’

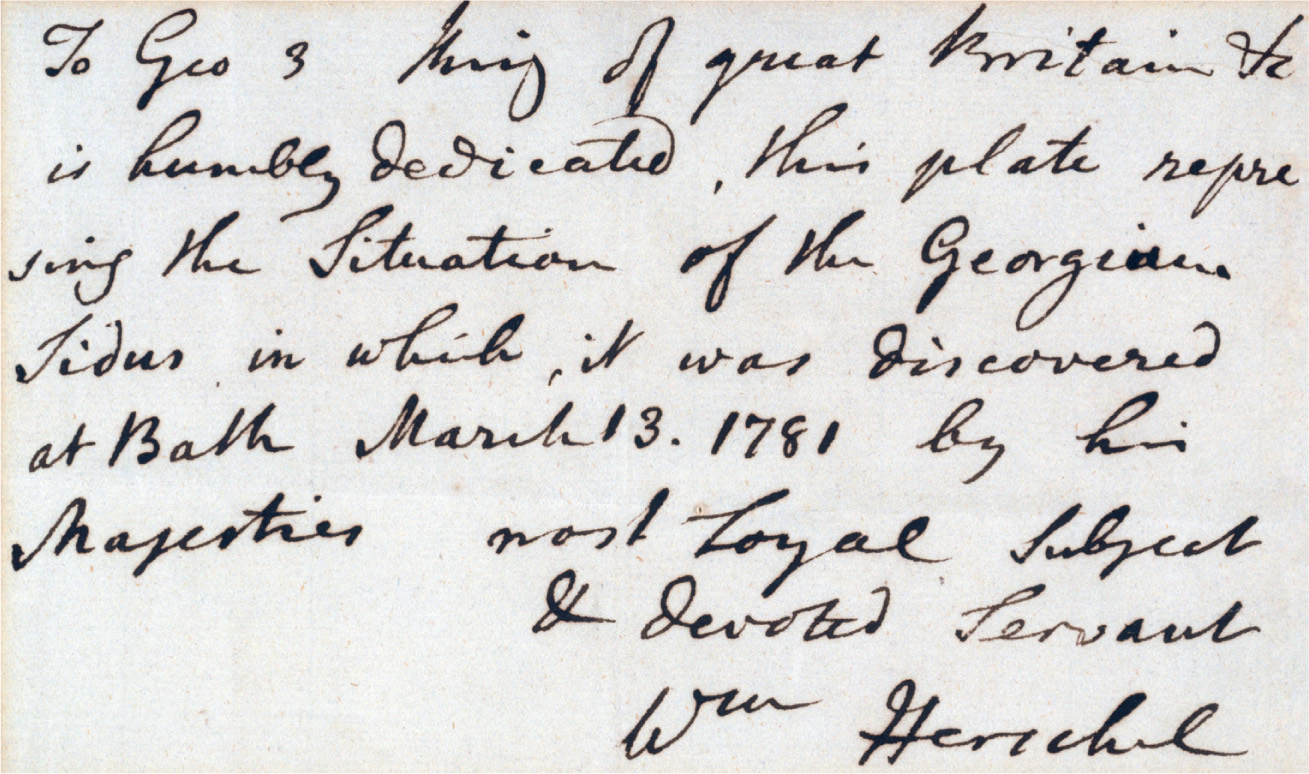

This was a crucial point. Planets move in roughly circular orbits around the Sun, staying at more or less the same distance. Comets dive in from the outer parts of the Solar System, swing past the Sun and head back out into the depths of space. Other observations confirmed Maskelyne’s speculation. In particular, the Russian astronomer Anders Johan Lexell calculated the orbit of the object from the available observations and showed that it was indeed nearly circular. In 1783, Herschel wrote to the Royal Society that ‘by the observation of the most eminent Astronomers in Europe it appears that the new star, which I had the honour of pointing out to them in March 1781, is a Primary Planet of our Solar System’. By then, he had already been appointed ‘King’s Astronomer’ (not to be confused with Astronomer Royal) by George III, with an income of £200 per annum, which enabled him to become a full-time astronomer.

In order to thank his patron, Herschel named the planet Georgium Sidus (George’s Star). But this did not go down too well outside the United Kingdom, and the astronomical community eventually settled on the name Uranus – with the stress on the first syllable. Ouranos was, in Greek mythology, the father of Cronus and grandfather of Zeus, who were Saturn and Jupiter in the Roman pantheon, fitting the place of the planet in the Solar System.