“I’ll prove I’m your true friend by not letting you get soused alone.”

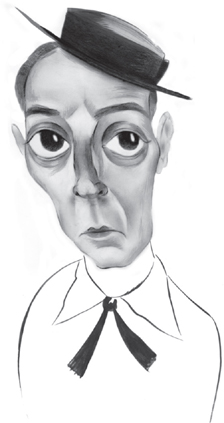

Buster Keaton’s talent as a silent film comedian is rated second only to Charlie Chaplin’s, and first by many. Nicknamed “Great Stone Face” for his unwavering stoic expression, his other trademarks were a porkpie hat and an astounding gift for physical comedy. Keaton started his own studio in 1920, and his streak of classic comedies from 1920–1929 is still hailed as an unparalleled run of flawless films. He did every one of his own stunts, including the classic chase on top of a train in his best-known film, The General (1926), a film considered by many critics to be the best comedy of all time. A move to MGM and the arrival of sound caused an unexpected lull in Keaton’s career, but he had a long and fruitful second act as a character actor and television star (The Buster Keaton Show).

CHRIST, WHERE AM I?” Buster Keaton was getting used to this feeling. A few weeks earlier, on Christmas morning, he had woken up alone somewhere on the MGM lot surrounded by the ruins of a party. He had cuts on his head. It took him a few days to piece together that he’d gone a little overboard at the studio’s annual pre-Christmas bash, trying (and failing) to do pratfalls after drinking an entire bottle of whiskey.

But this was a little more confusing. The last thing Keaton remembered was being at home in the Cheviot Hills area of Los Angeles, a few days after Christmas. Now, as the fog cleared, he found himself in a room he couldn’t quite place, probably because he’d never been there before. The mystery of his location, however, could be solved just by looking out the window: He was in Mexico.

Keaton usually went to the Agua Caliente resort and casino in Tijuana. During prohibition, Agua Caliente was the day-trip of choice for the Hollywood elite—a resort hotel with a racetrack, spa, golf, tennis, gambling, prostitution, and most important, booze. But Keaton definitely wasn’t there now. This, curiously, was the nearby town of Ensenada. A woman slept next to him. Unfortunately, he knew who she was: the nurse MGM had hired to keep him sober.

MGM decided to hire a full-time nurse, Mae Scriven, to keep him off the bottle. Clearly, that hadn’t worked either. Buster quickly seduced her, and soon enough the pair of them were going on benders together.

For his past few films, MGM had mandated sobriety and would check Keaton into the Keeley Institute before production started. The Keeley method was simple. Upon arrival, you would immediately be put on a rigid liquid-only diet: whiskey, gin, rum, beer, brandy, wine. You’d get a drink every half hour. You’d throw up when necessary to avoid alcohol poisoning. After three days, you left swearing that you’d never touch another drop. It is a practice still in use, now known as aversion therapy.

But when Keaton went through Keeley before the picture he was currently shooting (What! No Beer?), the cure didn’t stick. He was drinking again within hours. And so MGM decided to hire a full-time nurse, Mae Scriven, to keep him off the bottle. Clearly, that hadn’t worked either. Buster quickly seduced her, and soon enough the pair of them were going on benders together. And although he hadn’t counted on the charade continuing this long, here they now were—in bed together, in Ensenada, Mexico. Scriven, at least, could remember everything.

Apparently, Keaton had suggested the trip a few days before New Year’s. It was now the second week in January. He couldn’t care less that he missed the mandatory New Year’s party at MGM chief Louis B. Mayer’s house. Or that he was holding up production of What! No Beer? He’d done that a million times before. If that was all the bad news, he was golden. Turns out it wasn’t. Mae Scriven cheerfully informed him that they were now Mr. and Mrs. Buster Keaton. On January 8th, they’d gone before a judge in Ensenada and had made it official.

For the rest of his life, Keaton could not remember a single thing about the wedding day of his “marriage of inconvenience.” What was far more likely is that he spent that morning in Ensenada thinking about his last marriage, to Natalie Talmadge, the nonacting sister of Constance and Norma. Or specifically, the fact that they weren’t yet divorced.

FOR ALMOST HALF A century, the Brown Derby was a Los Angeles institution, the first and finest purveyor of upscale comfort food. Its building, which was literally shaped like a brown derby hat, became an icon of studio-era Hollywood. When it opened in 1926, actors and executives loved its late hours (open until 4 a.m.), its ostentatious policy of delivering phone calls directly to your table, and its semiofficial policy of only hiring attractive women for its waitstaff. The in-crowd sat in VIP booths that circled the room, while fans could occupy tables in the center to catalog their idols’ every bite. Charlie Chaplin, W. C. Fields, and John Barrymore were regulars. Co-owner and playwright Wilson Mizner had a standing claim on Booth 50.

A second location opened in 1929 on Vine St. It soon became the hottest lunch spot in Hollywood, decorated with caricatures of the stars that ate there—which were judiciously rotated based on the subject’s standing in town. Clark Gable proposed to Carole Lombard in Booth 5. Stars began getting their fan mail delivered there. Predictably, Hearst gossip queen Louella Parsons eventually pitched a tent and became the most powerful career-maker (and -breaker) in American celebrity journalism. Her nemesis, Hedda Hopper, later took over the other half of the room.

The Derby continued as one of Hollywood’s finest restaurants until the late 1980s, by which time both restaurants had closed for good. The original location had a strip mall built around it, and today the signature derby sits incongruously among insurance brokers and cell-phone hawkers. The dome itself houses a Korean bar popular among hipsters.