“I don’t really know why, but danger has always been an important thing in my life.”

A clean-cut and traditionally handsome (on screen, anyway) leading man, William Holden established himself as a serious talent with the Oscar-nominated starring role in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950). Holden won the Academy Award three years later, for his performance as a prisoner of war in Stalag 17. He headlined numerous war pictures through the 1950s—The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1954), The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)—while also proving himself as a romantic lead. His career hit a lull in the 1960s but was resurrected with his appearance in Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969). Holden received his third and final Oscar nomination (for Best Supporting Actor) as a television news executive in Network (1976). He divided his time between Hollywood, a home in Switzerland, and a wildlife preservation in Kenya, of which he was a partner. A dedicated boozer, he was convicted of vehicular manslaughter for a 1966 drunk-driving accident in Italy. And in 1981 he bled to death in his Santa Monica home after cracking his head on a table in a drunken fall.

FOR ALL SHE KNEW, this was typical. Kim Novak was still new to Hollywood. In the last year (her first in the business) she’d made three pictures, and this one, Picnic, looked like it might be the biggest yet. After all, she was starring opposite William Holden—the same William Holden she and a gathering crowd in Hutchinson, Kansas, could now see some fourteen stories up at the Baker Hotel, dangling from a windowsill.

Holden had always been something of a daredevil. As a boy growing up in Pasadena, he’d once crossed the famed Colorado Street “suicide bridge” (where many local residents jumped to their deaths during the Depression) walking on its outer railings … on his hands. The only thing that ever truly frightened Holden was acting, and for that he had alcohol. Billy Wilder once told a Time reporter that Holden was an “inhibited boy” and that he drank to “pull himself together.” He routinely took two shots of whiskey before a scene. And his office at Columbia was fully stocked at all times with top-shelf liquor, making it one of the most popular hangouts on the lot. Dean Martin, unsurprisingly, was a frequent guest, but there was no shortage of heavy drinkers to chum around with. Sterling Hayden was a dear friend, as was Dana Andrews. Ronald Reagan was a good pal, too, though far more temperate.

In fact, Dana Andrews tells a story about a night when Holden, Reagan, and he went to dinner following a Screen Actors Guild meeting. All three friends ordered drinks and chatted away. When the waiter returned, Holden and Andrews ordered a second round. Reagan was perplexed, “Why do you want another drink? You just had one.” As Andrews would later point out, “See what happened—Bill and I became alcoholics, and Ronnie became President of the United States.”

Of course hindsight is 20-20. Novak wouldn’t find out until many years later what Holden was doing dangling up there on the fourteenth-floor windowsill of the Baker Hotel. As a newcomer, she didn’t feel it was her place to question the leading man. But what she would eventually learn was that, on that day, Holden’s natural courage had been amped with a healthy dose of liquid courage—in the form of martinis, to be specific. It seems he and the director of Picnic, Josh Logan, were discussing the film’s final scene, in which Holden’s character, Hal, says good-bye to Novak’s character and jumps aboard a moving train. Holden was trying to convince Logan they could do it all in one unbroken shot—and that he could personally perform the stunt. Logan refused to consider it; it was too dangerous. So to prove his point, Holden jumped out the window of Logan’s suite and hooked his elbow over the sill. Actress Rosalind Russell, who was there, too, begged him to come back inside, but this only caused Holden to hang by his hands. Logan turned away, refusing to look. There were pleas to reenter, as Holden started to lift his fingers one at a time, until he clung by just two. Logan, too, now begged Holden to come back inside. Holden told him he’d only do so if Logan looked. Finally, Logan did.

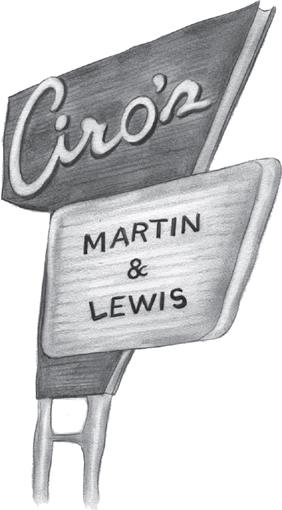

A FEW YEARS AFTER entering the nightclub business with the ultra-exclusive Café Trocadero, Hollywood Reporter founder Billy Wilkerson cemented his status as impresario of the Sunset Strip with this swank playground for the industry elite. Taking over the space that once housed Club Seville—a garish and ill-fated monstrosity where patrons were wowed (or not) by the prospect of dancing the night away on a glass floor laid atop a pool filled with live carp—Ciro’s opened in January 1940 to the same steady thump of self-generated publicity Wilkerson had employed at the Troc’.

“Everybody that’s anybody will be at Ciro’s,” his full-page ads in the Reporter said, and from the start the ads were on the money. One could spy Sinatra or Bogart, Marilyn Monroe or Judy Garland, Cary Grant or Spencer Tracy, scattered among the banks of silk sofas lining the club’s perimeter. Xavier Cugat was a regular headliner on the bandstand, as were Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis in the years before they became the biggest act in show business. In 1951 a group known as the Will Mastin Trio played Ciro’s as part of an Academy Awards afterparty, launching the career of its youngest member, Sammy Davis, Jr.

Given Wilkerson’s background in news, it’s no wonder the antics at Ciro’s, real or imagined, often made it into the scandal sheets. One of the most notorious rumors, and likely just that, involved the exquisite Paulette Goddard, film star and one-time wife of both Charlie Chaplin and Burgess Meredith. Supposedly, in 1940 not long after Ciro’s had opened, during dinner with European director Anatole Litvak (The Snake Pit), Goddard’s shoulder strap popped. Some accounts described Litvak as trying to shield Goddard’s exposed chest. Others would say diamonds fell to the floor. Whatever the inciting incident, it caused Litvak to drop under the table where supposedly, in full view of the other patrons, he made love to Goddard in what was described at the time as the “French fashion.” This despite Litvak being Hungarian. The story caught fire and, while nobody was found to have actually witnessed the event, it would plague Goddard for the rest of her life.

Scandalous indeed—but the nightclub’s crowning moment wouldn’t come until years later, on April 8, 1947. No rumor, this was the night Frank Sinatra punched Hearst columnist Lee Mortimer outside the club. Mortimer had written a series of widely read columns alleging that Sinatra was a communist and a supporter of fascist dictators. This insanity had been brewing since 1945, when Sinatra began speaking out against segregation, racism, and religious bigotry. And not just speaking out in some canned magazine story; he sang about it in the Oscar-winning short film The House I Live In (1945), he wrote high-profile letters to newspapers, and he performed at a high school in Indiana white students were boycotting due to a recent order of integration. In House, he said anyone who couldn’t see these fundamental truths was either an idiot or a Nazi.

Eventually, someone decided it was time to shut him up. And Mortimer, a red-baiting Hearst stooge, almost succeeded in destroying Sinatra’s career: The name “Sinatra” was uttered during at least a dozen HUAC hearings. MGM Pictures, Columbia Records, Sinatra’s radio station, and his agent all dropped him within months.

Then he clobbered Mortimer at Ciro’s. When Mortimer filed a lawsuit, Sinatra claimed that Mortimer called him a dago. But it was Sinatra’s reputation that took a beating, and a jury trial looked sure to make things worse. Even though he settled the case, everyone in Hollywood, with the exception of his friends, thought Frank’s career was over. And for the next four years, it was.