Embryonic Parachutist!

The first party left on operations on 31 December and the remainder of the squadron, except for myself and my twenty remnants, left Kabrit about a week later. It was very depressing to be left all alone but fortunately the parachute course took my mind off things.

Parachuting had largely been discarded as a means of getting the regiment to their objective, but nevertheless the colonel insisted that all new recruits should go through the course, and thus be ready to jump into action at any time. The chief reason, I feel, for the course was that it sorted out the recruits; if they could stand up to jumping out of a plane into space, then it showed that they had at least some of the qualities that made up the sort of man who was required.

The course took place about 3 miles from our camp at Kabrit and was very efficiently run. It lasted two weeks on the ground, after which, five jumps from a Hudson had to be completed. The instructors were a mixture from the Army PT School and from the RAF, and a better bunch of men one could not hope to meet. They knew their job very thoroughly and combined such cheerfulness with their efficiency that we all came to enjoy the strenuous physical exercise which the training involved.

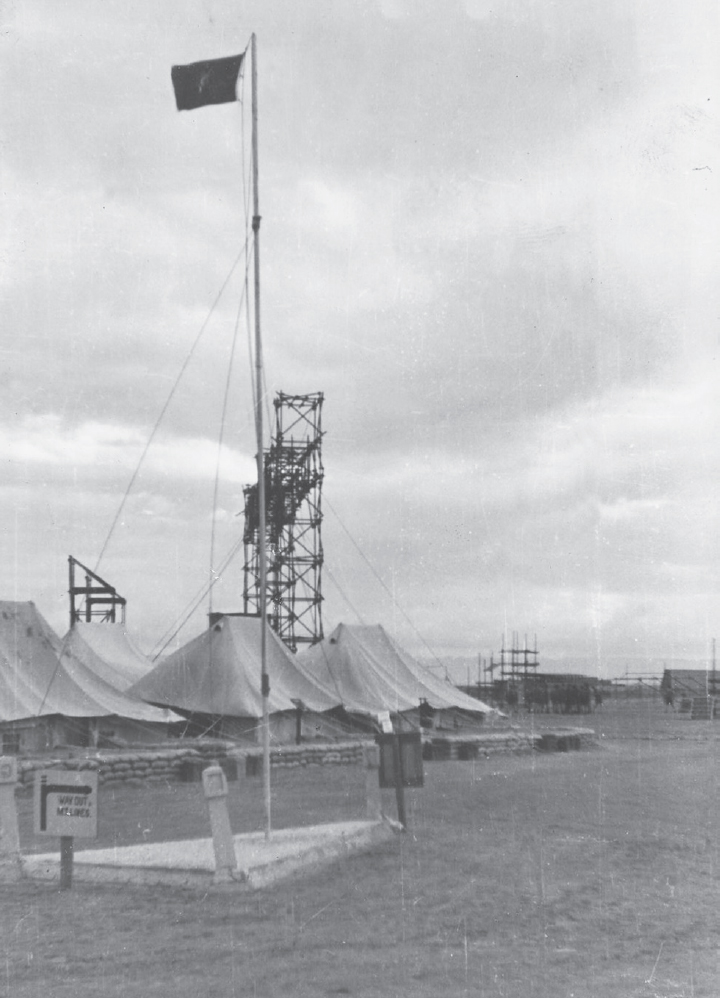

No.4 Middle East Training School, must have looked a strange sight when viewed from the Suez–Geneifa Road. Gigantic towers and platforms of steel scaffolding reared themselves up into the sky and aeroplane fuselages lay scattered on the sand in careless confusion.

We first reported to the METS (Middle East Training School Paratroops) on 22 December, the day after the squadron arrived at Kabrit. There followed two weeks of strenuous physical training during which, in addition to reaching a state of physical fitness which most of us had never before achieved, we were made to go through on the ground a synthetic parachuting training which was designed to acquaint us not only with the drill which had to be learned, but also with all the sensations the parachutist experiences when he actually jumps. By the end of those two full and gruelling weeks there was nothing we required to know about the art of parachuting and all preparations were made for our first jump.

But we were not to jump on the day scheduled. That night one of those sudden Egyptian storms arose, bringing along with it a strong gusty wind which whipped the sand into every corner of the tents and messes, and created conditions which were quite out of the question for parachuting, let alone for flying! So none of us was surprised to be told on the next morning’s parade, that the jumping was postponed until the following morning. This procedure went on for four days, whilst the storm continued to rage in unabated strength, so that the fear of the pending ordeal gradually diminished and the stark reality of the whole thing grew less. As I went to bed each night, and heard the wind battering at my tent, I was able to heave a sigh of relief, and say, ‘It’s not tomorrow, at any rate!’

Kabrit, Egypt, December 1942 to March 1943

Orderly room, Kabrit, showing swings.

Parachute hanging sheds, Kabrit.

And then one morning after going off to sleep with just that thought in my head I woke to the awful realization that the storm was over. All was still outside, and conditions were ideal for jumping. Quickly dressing in all the various knick-knacks that went along with jumping, I reported to the packing sheds where we were told that jumping would take place that morning. So this was it!

There was a funny dry feeling in my throat and a heavy feeling in my stomach, as I drew my chute, and I wished I had not had so much breakfast. And then began the waiting. Very few people seemed completely at their ease. Some were quieter than usual, but on the whole there was an atmosphere of forced merriment, all being unnaturally hearty.

There were seven in my stick and we had to jump in pairs. As I was the officer, I was made to jump in the last pair and I was thus the first into the plane. At first everything was exactly the same as the ground training: the inspection of our harness by the dispatcher, entering the plane, crowding into the nose as we took off, and then assuming our proper positions. The dispatcher came round to hook each of our static lines onto the strongpoint, and to ensure, personally, that the safety pin to prevent the claws of the clip from accidentally opening was inserted. All the time we kept up a running flow of hearty, cheery conversation and anecdotes, to try to take our minds off the present. He made us all promise to say cheerio to him as we went out, in the hope that we would worry more about this little detail than what we were actually about to do. I must confess that I was not feeling at all happy, and from the look on their faces, I imagine none of my companions were either. I felt very cold all of a sudden, as though I were even then exposed to the violence of the slip-stream that I could feel rushing passed the plane. At least three times I examined my static line to make sure that I was properly hooked up, and once I was satisfied to that effect, I could not keep my eyes from the door. This seemed to exercise a malignant attraction for me. Half of me wanted to go as far away from it as possible, while the other half felt a peculiar desire to hurl itself out.

Parachute training course, No 4 Middle East Training School, Near Kabrit, January 1943.

Such were my feelings then, as we sped towards the dropping ground. I most certainly had not the slightest desire to jump, and yet I was possessed by an even greater fear than of passing through that door – the fear of appearing afraid and maybe of refusing. And then, as I gazed out of the window, I saw below me on the dark sand, a little patch of white, arranged in the form of a T. Something jumped up in the region of my stomach and was still. We were there. The T was laid to show us as we descended in which direction the wind was blowing, and of course, to show the pilot where to release us.

‘Running in!’ the dispatcher’s shout seemed to awaken us from a bad dream. I saw the first pair leave their seats, and the number one take up his position in the gaping doorway. I felt myself gripping tightly the edge of my seat, for fear that, by some lurch of the plane, he should prematurely be sent hurtling into space. At that moment I felt that I would never be able to bring myself to stand in the doorway like that!

‘Action stations!’ The atmosphere inside was electric. The number one was straining in the door half inside and half out of the plane. So keyed up were his nerves that it would have only been necessary for someone to speak for him to have gone out. But he did not have long to wait. The red light above the door could not have been on for more than a couple of seconds, before the frenzied shout of the dispatcher ‘Go!’ informed us that it had turned to green. Numbers three and four prevented me from seeing these first exits, and all that told me they were out, was the sharp crack of the static line extending and the bump as the empty parachute bag hit the tailplane. There were now only five of us left in the plane, excluding the dispatcher. He, in contrast to our decidedly mixed feelings seemed to be enjoying himself hugely. He peered out of the door, and with great glee told us that the first two were on their way down successfully. How I wished I could have changed places with one of them!

A few minutes later, the same procedure was carried out and numbers three and four went out successfully, leaving only three of us to jump on the following circuit. I began to feel rather sick and colder than ever. I had noticed with horror the speed with which they seemed to be whipped around the corner as soon as they had got one foot outside. It appeared to be such very violent treatment.

As we made the final circuit the three of us who remained were made to move right up beside the doorway and soon the by now familiar order, ‘Running in’ was applied to us. Slowly we got to our feet and lined up, the one behind the other. Phillips, the number one, took up his position in the door and from where I stood I could see his face clearly, as, with one hand on each side of the doorway, he balanced himself on the threshold with nothing but a few inches separating him from space. The sweat stood in beads on his brow, as we ran in, and his jaw was moving rhythmically and mechanically, as he chewed his gum. The shout of ‘Action Stations!’ woke me from my study of Phillips’s face, and I realized that I only had a few seconds to go before I would be hurtling through space. My stomach felt as though it weighed a ton and every nerve in my body was so tense that I would have jumped had a pin been dropped. Fascinated I watched Phillips, trying to forget my own fear in the contemplation of his. What was wrong with that red light? Surely it should have turned to green ages ago! Just as these thoughts were flashing through my mind, the dispatcher bawled ‘Go!’ in my ear, and muttering a prayer I prepared for the very worst, never having felt so afraid in all my life. An expression of determination, mixed with repulsion crossed Phillips’s face, and he made a half-hearted attempt to push himself out with his hands, in the manner taught. But his chute got caught in the top of the doorway and the slip-stream must have been a good deal stronger than he imagined, for when I looked again expecting to see Elwys, the number two, disappearing, Phillips was still in his ‘action stations’ position and the plane had passed over the dropping ground, so that we had to make another circuit.

Parachute training course, No 4 Middle East Training School, near Kabrit, January 1943.

Something was bumping violently inside me. Oh why can’t we get it over with, I found myself muttering, while I was cursing at having to undergo that awful circuit once more. The instructor was muttering reassuring words of advice in Phillips’s ear and I watched his strained and anxious look and the mechanical movement of his jaw, while I wondered if he would make it the next time round. I was not sure how I myself would feel when I stood in that doorway and saw the ground rushing past beneath me. The red light went on again and the tense feeling increased. I noticed in an objective sort of way that I was sweating hard, though I was strangely cold.

‘Go!’ shouted the dispatcher and Phillips went. Before I could realize that my last hope had now gone, Elwys had disappeared and I found myself in the gaping doorway. I don’t remember jumping: the next thing I remember was being gripped by an almighty wind which pulled me horizontal and filled me with sheer terror. As if in a dream I noticed the side of the aircraft flash past me, and forgetting all the lessons we had learnt on the ground, I clutched madly in the direction of the tail plane, anything to save myself from this awful sensation of powerlessness. And then before I even felt myself to be falling, came the welcome tug and I looked up to see the lovely white canopy billowing out above my head.

Peter Davis before first jump.

Before first jump: Frame, Little, Unknown, Tunstall, Phillips, Elwys.

In spite of my shocking exit, for I realized that I had gone out in one mad flurry of arms and legs, everything was completely in order. I was sweating harder than ever and felt boiling hot; after I had settled myself comfortably in my harness and grasped the lift-webs above my head, I took the opportunity of looking around me. The silence with which I was now surrounded was a wonderful contrast to the noise and the vibration of the plane. Everything seemed so peaceful, with the sun shining in the cloudless sky and the yellow sand below, that I found my terror of a few seconds before rather difficult to understand and one of my first impressions was, ‘You old fool, what on earth did you make all that fuss about.’

I could see Phillips’ and Elwys’s chutes slightly below and to the left of me. It was good to know that they had got out safely. I felt on top of the world as I drifted peacefully downwards. Save for the quite considerable swing from one side to the other, there was absolutely no motion at all until I was only a short distance from earth. By this time, the instructor on the ground had started making some rather pointed remarks through a megaphone on the subject of keeping one’s legs together, and just in time I remembered the landing training that we had gone through earlier on in the course. I managed to do a three-quarter turn, which put my right side to the wind, as the ground came rushing up at me. I hit it hard, but in accordance with my training, I crumpled up, rolling sideways onto my right shoulder and with a strange feeling of elation, picked myself up unhurt and ran round my chute.

After I had folded this up in the approved manner, I went back to the truck where the rest of the stick were waiting, in spirits very different from those of only a few minutes earlier. Everyone was talking and describing their experiences, and the general impression was that the whole business was not nearly so bad as our imaginations had caused us to believe it would be. But the next time we went up, the tension, and the strain, and the silence in the plane, were as apparent as they had been before, and for my part at any rate, the sensation of sheer panic as I went through that door never diminished. The high spirits that were displayed on the ground after the jump was over, were certainly no criterion by which the pleasures of parachuting could be judged, as they reflected nothing more than the welcome release from the considerable nervous tension, to which we had all just been subjected.

I accomplished my remaining four jumps successfully in the following three days, after which I was able to celebrate the completion of my course by spending a weekend’s leave in the magic city of Cairo!

I shall never forget that first trip to Cairo and the sight again of large hotels and civilized surroundings. I started my leave by joining in the drinking that went on round the bar under the auspices of the very efficient barman, Corporal Leitch, who was up half the night attending to our wants and having a quiet laugh at the officers in the shelter of the bar. I had often heard the expression ‘a dour Scotsman’ but its meaning was never really clear until I met Corporal Leitch, who fitted the description admirably. He never said two words where one would have sufficed and always gave the impression of having a rather jaundiced view on life, especially when there was no whisky to be had!

At the bar I met John Bell, an officer the same age as me, and who had arrived at about the same time. Johnny was a frank, sincere and conscientious chap, whom one could not help liking and we immediately struck up a friendship. As we drank and chatted, a stranger came up to the bar beside us. There was nothing spectacular about this visitor; on the contrary, in fact, he was a mild, kindly-looking old gentleman, whose youth was already well behind him. He seemed perfectly at home in the mess, and as soon as he had reached the bar, began to sink pink gins at a prodigious rate. He soon started up a conversation with Johnny and me and revealed that he was far from being the mild old gentleman that he appeared. He was the revolver-shooting specialist, Major Grant-Taylor, and must have been the best shot with the revolver in the whole of the Middle East. He had started a course in the pistol and close combat methods which many of the unit had already attended, and at which I was lucky enough to be present a few months later. Apparently this meek looking little man was able to give one of the most blood-curdling and morale-boosting lectures on the offensive spirit that has ever been delivered. But I did not know all this about him then, and we chatted until well into the following morning while one pink gin after the other slid down his throat.

Parachute training near Kabrit, January 1943.

There is nothing impressive about the trip to Cairo from Kabrit. I cadged a lift in a Jeep the following morning which brought me safely to the city by lunch time. Although the distance is about 90 miles the road is so flat and straight that the trip can be comfortably completed inside two hours. No town or village lies on the route and, as far as the eye can see, the road runs for the whole distance through a stretch of flat, sandy desert, sprinkled here and there with patches of brown camel grass and scrub. Rocky hills rose up in the distance for the first part of the run, but soon even these were left behind and nothing except the kilometre stones that lined the roadside gave indication of how much of the distance was yet to be covered. Almost exactly half way was the Half-Way House, which catered for the weary traveller and where, at regular Spinneys prices one could obtain a meal or a cup of coffee and a dry bun.

One or two army camps were dotted about here and there along the roadside, but the very bleakness and monotony of the landscape always made it seem something like a miracle when, after topping a long gentle rise, the great city of Cairo came into view. It seemed unnatural and out of place somehow. Before you realized it, you were in the city with its teeming pavements and hooting taxis, rattling gharries and clanging tramcars, with its fine modern buildings, its primitive native houses and its spacious and beautifully kept parks. Only 2 miles outside Cairo you might still have been in the middle of a vast desert, thousands of miles from any civilization. I could not quite believe it and all of a sudden felt rather lost in the middle of this noisy, active and hurrying throng.

Cairo was a wonderful city if one went there just to have a good time, with the intention of spending an unlimited amount of money in a limited space of time. It can truly be said that anything could be bought in Cairo at that time, for a price. But food was reasonably cheap and plentiful, and so the best part of a weekend’s leave was spent in eating and drinking. Hotel accommodation was desperately short, for officers at any rate. A room to yourself was an unheard of luxury, for the Cairo hotels used to squeeze as many beds as possible into all their rooms, so that we got the impression of sleeping in a dormitory. But nevertheless, the price of a room was demanded from each of the occupants, so the war must have certainly been welcomed by the Cairo population.

I met up with Douglas Stobie and Ken Lamonby, two officers who had just joined the regiment, and we spent the rest of my leave together. We soon learned that one had to have one’s eyes wide open in Cairo, if one did not want to be fleeced right and left by the civilians. It seemed a point of honour with the Egyptians to make as much money as possible out of the unsuspecting British soldiery who went there to spend their leave and have a good time. In this, the Egyptians did not bear the whole guilt for Cairo is such a cosmopolitan place that one comes across all nationalities there, especially Greeks, Turks and French. But no matter what the nationality, their intention was the same, to make use of the war to their greatest possible advantage, by making the celebrating and pleasure-seeking Eighth Army leave-troops pay through the nose for everything.

So that was Cairo – a city where anything could be bought at a price, where for a short leave, a wonderful time was to be had, but where the characteristic Arab graft and love of money was rampant.

Back at Kabrit I busied myself with getting to know my twenty-odd men, keeping them well occupied and preparing them for operations to the best of my ability. Soon all of them had successfully gone through the parachute course, except for one who refused and another who fractured his spine on landing, and who consequently never returned to the unit from hospital. Training hours were not long and we enjoyed plenty of free time. The day started with reveille being blown on the bugle and half an hour later, at half past six, we had to double out into the chilly misty morning, onto the square by the boxing ring. There Company Sergeant Major Instructor Glaze, our jovial PT instructor, put us through our paces with a rigid set of exercises, followed by assault course training on the parachuting apparatus. Twenty minutes later it was a weary body of men who returned to their tents to dress for breakfast. But irksome though this training might have been, it certainly made us fit, which was to serve us in such good stead later on. Training hours were from half past eight to half past four and mercifully I was given a completely free hand in how I arranged it.

The original adjutant of the camp when I first arrived, had been so ‘guards’ that he seemed to be surrounded by a veritable halo of spit and polish, and was only remarkable for his extreme lack of intelligence, but he was succeeded by John Verney who, despite being unacquainted with the job, could not have done better at it and was a joy to work under. All he wanted from me was a weekly training programme, and in return I could always rely on him for help in arranging exercises etc. To begin with, we concentrated entirely on driving and navigation, demolitions and firing foreign weapons, and it did not take long before I had all my men fairly adept at these subjects. We were only passing the time away as profitably as possible, for we were under the impression that on 25 January, we would be going up to join the squadron and thus were very determined to learn as much as possible.

But in this expectation our hopes were once again dashed, for on 22 January, Tripoli fell to the advancing Eighth Army, and we were told that there was no scope for us and that the squadrons would shortly be returning. I was very disappointed, for it seems strange to spend eighteen months in the Middle East, without once having taken part in any of the desert operations, and it is something that I shall always regret. But we had no alternative but to remain at Kabrit making the best use of our time as possible.

Peter Davis at Kantara Station, Palestine, March–June 1943.

Excellent instruction was given us in demolitions by Bill Cumper’s engineer section. A wonderful character was Bill. He possessed the most cheerful disposition and quickest wit of anyone I have known. He had risen through the ranks, and was now a permanent fixture in the regiment. If anyone felt depressed they only had to talk to Bill for a few minutes and I defy them to have kept a straight face for long. Since I am rather small in size, Bill always called me ‘Chota’, and I do not believe to this day that he knows my real name. In the mess he was always remarkable for the fact that he never drank anything stronger than a lemonade although, on occasions he was known to add a dash of lime, to keep his spirits up. But it was surprising what an effect these drinks could have on him, for he could hold his own even in the most hilarious of parties, and it is only further proof of the spontaneous cheerfulness of his nature that he never felt tempted to stimulate it by artificial means. Bill was a ranker and proud of it; he would often come into the mess, chose an empty seat next to a newly arrived young officer, asking permission to sit next to the ‘officer’, and then in a loud voice would inform the mess waiter that he was ready for lunch, by telling him that he could bring in the ‘swill’.

It was a great event when ‘Jumper’ Cumper was going through his parachute course, and on the occasion when he had done two out of his five jumps, he came strolling quite unconcernedly into the mess, with two fifths of the parachute wings sewn onto his sleeve, which he proudly displayed to as many people as he could.

Bill was extremely violent in his declamations against the ‘spit and polish’ brigade, and he kept his independent character, no matter who he had to meet. The story goes that when the Duke of Gloucester inspected the camp, Bill absolutely refused to wear a ‘Sam Browne’ in his honour, and he is reported to have greeted the royal visitor with the words, ‘Hello, Duke, meet the lads!’

This same individuality and lack of embarrassment which he displayed towards his superior officers, was revealed to the full when Bill was in action. Nothing scared him or caused him to lose his light-hearted, carefree attitude. When the regiment was raiding Benghazi, they found their way barred by a gate. Bill, who was in one of the leading Jeeps, jumped down and with a flourish and many exaggerated gestures, threw it open, in a loud voice proclaiming as he did so, ‘Let battle commence!’ No sooner had he done this than the enemy who were in prepared positions nearby, opened up with all they had got and battle certainly commenced with a vengeance.

No one could help liking Bill and he remained always one of the most popular figures in the regiment, a first class technical engineering officer, as well as a sincere friend and a most amusing companion.

Peter Davis, Cairo, January 1943.

Outside the camp there was not much in the way of amusement in the immediate vicinity, except for the local cinema, and it is proof enough of how the men found time hanging heavily on their hands, that this was so remarkably well patronized. The Egyptian cinemas were indescribably awful and it was always a source of wonder to me how the authorities allowed such conditions to exist. Apparently they had accepted the offer of a local contractor to provide entertainment for the troops in the canal area, and paid him vast sums of money for this purpose. But he must have made his fortune out of the contract, for everything was skimped and shoddy. The buildings themselves were foul and many of them actually waved about in the wind. The seats were hard, uncomfortable and sordid and the sound system was so distorted that it was impossible to hear. The films were so old that they were always breaking and the operators were so amateur at their job that often they would show separate parts of the film in the wrong order! The troops took all this in very good humour, I thought, and usually just went to have a good laugh at their primitive surroundings. However, I cannot blame them in the least for the few occasions when they felt they had had enough of a good thing, and had set fire to the whole wretched contraption.

And now I think it opportune to say a few words about various people I met and with whom I had to work at Kabrit. As I have already mentioned, very few of the operatives were at the camp, as both ‘A’ and ‘B’ Squadrons were chasing up the German retreat at the time I arrived in the regiment and were now somewhere in the vicinity of Tripoli. The camp was left in charge of an elderly non-operative major, whose job it was to look after the administrative and disciplinary side of things in the absence of the colonel. He was a typical regular soldier, of the type who had worked his way up from being a ‘boy’ in the regimental band, and as a result he was not too easy to work under. As far as I could see he had only two thoughts in his head: one was whether anyone had dropped a piece of paper in the camp area recently, and the other was how many officers and men were dodging doing their day’s work.

He paid far more attention to the cleanliness of the camp than to the welfare of the men and to their training, and he had not been in charge long before the roads in the camp were all lined with stones. Woe betide the man who accidentally tripped over a stone and dislodged it in his sight – he could be sure of extra fatigues for that! The stones had not been there long before Pat Reilly, the regimental sergeant major, was summoned to the orderly-room, and instructed to find a fatigue party to paint these stones white without delay. Pat was rather taken aback at this strange request, but after a second’s hesitation, came out with the reply, ‘Oh yes sir; and shall I get them painted on the underside as well?’

These two did not get on well together as may be imagined, for whereas the major stood for pettiness and unnecessary, trivial discipline, the RSM ruled the camp and the sergeant’s mess with an iron hand. So long as everything was going all right he would have nothing to say and gave the impression of being a jovial, friendly person, but as soon as the slightest thing went wrong he was there on the spot and ready to tear a strip off anybody. His one concern was to keep the camp running efficiently and anyone who did not help him towards this goal soon paid for it.

Pat was a massive Irishman, standing about 6ft 3ins, and weighing close on 15 stone. He shared with the leading figures of the regiment, such as Paddy Mayne, the quality of possessing extremely high powers of observation. He would walk about the camp, giving the impression that he was easy-going and carefree and yet all the time, there was not a thing that escaped his notice. And once he noticed anything, he was certainly not slow to act. Pat was the best RSM I ever met in the army. He was not only respected, but admired by the men, from whom he kept exactly the distance that his rank demanded. In his treatment of them he was completely fair, whilst his ability to judge character, which never led him wrong, was something in the nature of a gift. And added to these qualities he was, purely as a man, one of the best types on this earth. Sincere, a good listener, and always willing to have a laugh at his own expense, he was one of the best natured people I have ever met.

It was natural that a man such as Pat Reilly had qualities which were wasted as an RSM, and thus it was not long before he received his commission, and returned to the regiment in that capacity.

I had been at Kabrit about a month when a startling rumour began to spread around, and shortly afterwards it was confirmed that Colonel Stirling had been captured. It was learnt later that he was almost certainly betrayed by the Arabs, for his party woke up one morning to find themselves surrounded by a crowd of fierce-looking Germans and all they could do was give themselves up. Two of the party lay low and managed to get away, and after a harrowing time, succeeded in making their way to the First Army lines. The news of the colonel’s capture was received with dismay at Kabrit and, down to the newest arrival, everyone regretted the loss of so inspired and distinguished a leader. The future of the regiment was now very much in the air, more especially since the wonderful advances of the Eighth Army had made the presence of the regiment in the enemy’s rear almost unnecessary. Shortly after the news of the colonel’s capture, ‘A’ Squadron under Paddy Mayne returned from operations, and after a few days reorganizing at the camp, and then some leave in Cairo, they went off to Syria to do the course at the ski-school in the Lebanon mountains.

‘A’ Squadron arrived back just on the day when General Alexander was inspecting the camp, and everything had been prepared to give him as good an impression as possible, when these bearded, dirty men began to come in. Poor Pat Reilly was tearing his hair trying to hide them all and his patience was put to the highest test, when Johnny Wiseman, a very small and amusing officer, chose to enter the gates sporting a magnificent beard, at the very moment when the general was inspecting the men. Not unnaturally, Pat failed to recognize Johnny and told him to clear off in no uncertain terms.

During their brief stay I hardly got to know any of ‘A’ Squadron, though I came to know them all very well later. However, I shall never forget my first meeting with Paddy Mayne, the squadron commander, under whom I was to serve for the next three years and who, in my opinion, was one of the most outstanding characters that this war has brought to light. I wanted to speak to Bill Cumper about some point to do with demolitions and was told that I could find him in Paddy’s tent. I walked in and was introduced by Bill.

My first impression of Paddy was amazement at the massiveness of him. His form seemed to fill the whole tent. Standing well over 6ft every part of his body was built on a proportionately generous scale: his wrists were twice the size of those of a normal man, while his fists seemed to be as large as a polo ball. Although he must have weighed close on 17 stone, there was not an ounce of surplus flesh on his body, and I was to learn later that his powers of endurance were unlimited. He seldom worried about keeping physically fit, and yet he could accomplish twice as much as the average man. He was made to look even more imposing, on the occasion of our first meeting, as his face was covered with an enormous reddish beard which he was just in the act of removing. But this could not hide his extraordinary profile, for he was one of those people with a dead straight forehead, so that from the top of his head to the tip of his nose was a straight line. Under great jutting eyebrows, his piercing blue eyes looked discomfitingly at me, betraying his remarkable talent of being able to sum a person up within a minute of meeting him. He received me most civilly and I was struck by the incongruity of his voice and of his shy manner, contrasting with the powerfulness of his frame, for his voice was low and halting, with a musical sing-song quality and the faintest tinge of an Irish brogue. I was soon to learn that when he was excited or intoxicated, this remarkable voice would become so Irish as to be hardly intelligible, and when he was angry it would reach such heights as to be almost a falsetto!

But on this occasion Paddy was courteous and charming, as he always was with strangers. He asked me a few questions about myself and the men left in my care, and then offered me the opportunity of going up to Syria with his squadron to go through the ski-course. I was very tempted to accept, but had to decline the offer, explaining that I was still hoping that Richard Lea had not forgotten me and that he would keep his promise and call me up to the desert shortly. It later turned out that this hope came to nothing and it would have been far better for me to have accepted Paddy’s offer.

A few days later Paddy came into my tent and asked if he could take one of my men with him. Naturally there was no reason for me to refuse this request, and moreover, I was hardly in a position to, but what struck me at the time, was that he should have the decency to come to me rather than summon me to him and tell me of his intentions. From the very first moment one set eyes on him, Paddy Mayne gave the impression of being a great man. Not indeed, because he was always showing it or talking about it, but simply from the terrific force and vitality that radiated from him. He was a man of very few words and was amazingly shy when he had to talk in public to the men, and I think his greatest pleasure in those days was to sit quietly in the mess, with a drink in his hand, watching in silence with those sharp, penetrating eyes of his, everything that was going on around him and making a mental picture for future reference of the private, individual character of everyone he observed.

There was nothing stuck-up about him; he would talk for hours to anyone, whether a man, NCO or officer, on terms of absolute equality. But it was a dangerous thing to imagine that by taking you into his confidence in this way, Paddy was showing you a sign of his special favour, for as likely as not he would not so much as look at you on the following day, and by just a look or a gesture, he was able to put himself at the correct distance from you. If there was one thing that he hated, that was a person trying to win favour with him, and it was a rare thing for anyone who practised any self-seeking motives with him to be allowed to get away with it for long.

There were many other officers I met during this stay at Kabrit with whom I was shortly to become much more closely acquainted. There was George Jellicoe who, although a shrewd and a capable leader, was the complete antithesis in character to Paddy Mayne. Possessing a strong personal charm and magnetism, he did not seem to conceive the seriousness and danger of the job that he was training his men to do, and used to lark about the mess on occasions like any high-spirited schoolboy. He seemed too light-hearted to take his job seriously, but people who knew him soon realized that this was only a pose. He was in charge of ‘D’ Squadron, a newly formed unit which was occupied with a rather different sort of training than that which had previously been practised by the regiment.

‘D’ Squadron concentrated on training in small seaborne raids, and shortly afterwards they split off from the rest of the regiment to undergo a most extensive training. It should be mentioned that by the end of 1943 they were known and feared by the enemy in Crete, Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily, Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia and all the islands of the Aegean and Adriatic. Many a volume could be written of the dangerous and daring ventures which they undertook.

Another prominent figure in the mess, was Captain Francis, the MTO, ‘Franco’ as we called him, who was a born staff officer. He had just the right walk, just the right suggestions of a comfortable paunch and that air of knowing all there was to know about every subject, without deigning to reveal his knowledge to anyone. As he walked over to the mess from the MT office, in his customary slow and dignified fashion, carrying the little black brief case under his arm which gave him such an air of importance, he seemed a great man indeed. But Franco was not such a bad sort at all. He never made himself out to be anything other than what he was and could join in the laughter at himself with the best of them. Once you took Franco for what he was, rather than for what he ought to be if you judged him for his stately exterior, he proved to be very good company.

‘B’ Squadron had meanwhile returned to Kabrit, and from all accounts they had had a pretty bad time of things and casualities had been extremely heavy. They were given leave and then remained hanging around the camp, pending the reorganization that we all knew was inevitable, as a result of the colonel’s capture.

By the beginning of March, I had given up all hope of getting out to the scene of operations. The Eighth Army was sitting in front of the Mareth Line, and there was absolutely no scope left for the regiment in this theatre. My squadron was the only one up now, and rumour had it that they were having a pretty good time in Tripoli and would shortly be returning. So we at camp just filled in our time as best we could.

My squadron returned about the middle of March. It was grand to see them all again, and to be able to chat with John and Ted and Mick and learn all their news. Apparently they had not done very much, for by the time they had got out there, there was hardly any useful work which they could do. In fact, beyond reconnoitering some of the enemy positions at the southern end of the Mareth Line, and taking some useful photographs of ready-prepared enemy defences which at that time were not yet manned, their time had been completely wasted. In fact they envied me having completed my parachute course, and having been able to spend the period more or less profitably.

A few days after the arrival of ‘C’ Squadron, as my squadron was called, Paddy Mayne’s ‘A’ Squadron returned from the ski-school in Syria, rather more quickly than they intended, as a result of the mysterious disappearance of a large amount of chocolate from some place or other where they had been. The whole regiment was now back in camp, and it was clear that now at last the long expected reorganization of the unit was to take place.

After the usual rumours it was learnt from fairly sound sources that the regiment was to split into two groups, one under Paddy Mayne, of about 250 strong, and the other under George Jellicoe of about 150 strong. Paddy’s squadron was to be called the Special Raiding Squadron, and Jellicoe’s was named the Special Boat Squadron. These high sounding names were meant to indicate to some extent the different roles that the two squadrons were destined to play, for the SRS was to be trained in parachuting and land operations, while the SBS was to concentrate entirely on sea operations. As it happened, when both units went into action some months later, it was the SBS who landed in small parties by parachute, while the SRS were landed in assault craft, but no one was to know that then.

Both squadrons were to be under a central headquarters known as HQ Middle East Raiding Forces. Heaven knows who invented these names, but modesty certainly does not seem to be one of his predominant virtues!

The question naturally arose, how was everyone to be fitted into this new organization, and it soon became clear that many people would have to go, especially among the officers. We were kept in suspense for a few days until one morning Richard called me into the office tent and told me that I was to be given a section of twenty men in the new organization. It can be imagined with what relief I heard these words, and I was even more pleased to learn that I could take with me the twenty or so men who had been left with me during all the time the squadron had been away on operations, and whom I had come to know and like, very well indeed. I was also told that the new squadron was to be divided into three troops, each troop being approximately equivalent to the three squadrons, as they then existed. But as each troop was to consist of only three sections and my present squadron could raise four, I would be the odd section, and would thus take my twenty men into a strange troop, and away from the squadron I knew. I did not like this news at the time, but had no reason to regret the change, for I found that I was in a rattling good troop, which I felt was considerably better than the one I was leaving.

And so it was that the old ‘A’ Squadron, formed No.1 Troop of the new organization. The old ‘C’ Squadron formed No.3 Troop, and the second troop was formed by a section from each of the three squadrons, for the old ‘B’ Squadron had suffered such heavy casualties in the desert that it could not raise much more than one section.

A day or so later, I was introduced to my new troop commander Captain Poat. Harry Poat was a typical Englishman of the old school with all the qualities and none of the defects. To look at, he was of medium height, very broad and tanned. He seemed to radiate health and energy. Two shrewd blue eyes surmounted a fair moustache, and no matter where he was he was always perfectly dressed! To speak to he was not striking. He gave the impression of never quite knowing what to say, and although whatever he said was sound common sense, and often even brilliant, the process of thinking it out seemed rather a strain, as though his brain was rusty and not accustomed to the effort of thinking. When he read it was at half normal speed and he would follow each word as he read it with the end of his forefinger, so that by the time we, looking over his shoulder had finished the page, he would only have read two or three lines. Harry possessed very fine common sense, which resulted in his being one of the finest officers the regiment produced, added to which he was as brave as a lion.

My fellow section commanders in No.2 Troop were Tony Marsh, captain and second-in-command of the troop, young, bouncing, blonde, and extremely good looking. He was always up to some trick or the other, would never seem to care about a thing except about having a good time, and yet in actual fact no one could be more conscientious and he knew everything there was to be known on the subject of training and of handling men. Unlike Harry, Tony preferred the unconventional in matters of dress, and unless he was wearing something slightly different from everyone else, he was not content.

The third section commander was Derrick Harrison, who had joined the regiment about a month after me, whereas Tony and Harry had come to it over two months before. He was one of those thin, nervous types, who can never do anything slowly. When he walked he would give the impression that were it not be for propriety he would far rather be running. He paid the strictest attention to detail and would dwell on small points which we thought not worthy of attention until he had got right to the bottom of them. He was intensely keen and interested in the training, almost to excess. But like Tony he was extremely human and sincere and we made good friends right from the start.

Our troop staff sergeant was Bob Lilley, a veteran of the regiment since its foundation. Bob is difficult to describe for I have never met another man like him and it is impossible to include him in any particular set type. He had had the worst possible education and yet had worked on his own and raised his standard, not only on the narrower issues, but on the wider ones also, and many is the argument he would have on economic, political and social subjects, in which he showed his sceptical views to be as unshakeable as a rock. As a sergeant in charge, he was excellent. There was rather a harmful tendency in the regiment for the NCOs to be scared of using their authority, for fear of being unpopular with the men, so that they would rather side with the men and not with the officers. Over-familiarity was a danger of which we always had to be careful, but if everyone had been like Bob Lilley, we need have had no worry on this score. The men disliked him, principally because he would stand for no nonsense from them. He was a fine example of loyalty to his officers and controlled the sergeants under him with an iron hand. Nor would he be content just to sit back and take shelter behind his rank. One of the men, who had more conceit than good sense, chose to accuse him of this on one occasion. Bob Lilley promptly took him outside and, in spite of the fact that Bob was getting along in years, being on the wrong side of forty, he gave him the good hiding he so richly deserved. Bob Lilley was just such a staff-sergeant that a good troop needed, and on whom his officers could rely completely.

About 20 March, the regiment took up its new formation. Paddy, in his shy, halting, barely audible speech, gave us a short talk, in which he informed us that we were about to start off on a period of very intensive training. What it was for no one knew, but we were told sufficient to show us that it was for some important job. Paddy also told us that we would be leaving Kabrit within the week for a new training area in Palestine which provided a more suitable terrain.

A few days later we were given a talk by our new colonel. His speech did not impress the veterans very much, but it hardly mattered, as we hardly saw anything of him. To all intents and purposes Paddy was the boss and took no orders from anyone. The new colonel was purely administrative, and much as he would have liked to, was given no opportunity of meddling with our training. In fact, we hardly ever saw him.

On the last night of Kabrit we had a wild party in the mess, which left the place looking as though a hurricane had passed through it. Our old naval friends of HMS Saunders, the camp next door, gave us a right good send off, and seemed genuinely sorry to see us go. The following night, we scrambled ourselves and our belongings onto the waiting transport, and amid waves, cheers and farewells drove off into the darkness to the station. In typical Egyptian fashion, our train had run out of coal on the way, with the result that it turned up eight hours late, so that we had to spend an uncomfortable night in the open. But nothing lasts and just after dawn the train actually condescended to arrive; wearily we slung our belongings in, and settled ourselves down to the long and tiring journey, which we knew was ahead of us, and which I had already covered once before. So it was goodbye to Egypt, and a new phase had started in our varied existence.