Invasion Training

We left Egypt about the beginning of April and arrived at Azzib (Palestine) after a typically slow, monotonous journey lasting over forty hours. As is usually the case with such journeys, our arrival was so timed that we reached our destination at about two in the morning, and in consequence, all the rush and bustle of de-training had to take place in pitch darkness. There was no station and we found ourselves up on the grass verge of the track, a very disconsolate group. But gradually some sort of order began to make itself felt, for the unit transport which had been taken up with the advance party arrived shortly afterwards, and was soon busy ferrying the men to the camp. Eventually I found myself a tent where I lost no time in getting stretched out on my bed.

I woke fairly late the next morning, and quickly got up to have a look around. Looking towards the sea about half a mile away, the main coast road could be seen skirting the hill on which the camp was situated, and this was fringed with orange groves of a refreshing greenness after the arid wastes of Egypt. Looking inland one could see the coastal range of hills which runs the length of Palestine, rising up beyond the intervening two-mile wide strip of cultivated land.

The camp itself was centred around the top of the hill, on which were situated the various messes and cookhouses, and the slopes of which were freckled with the tents of the men’s lines, neatly arranged by troops.

It did not take us long to find out where we were. The camp lay on the coast road about 20 miles north of Haifa, and 3 miles south of the Syrian border. A mile or two to the north of it lay the small arid village of Azzib, and the same distance to the south was the small Jewish holiday resort of Nahariya.

Around midday, of that first morning Paddy summoned a meeting of all the officers, in order to lay down the procedure of training that was to be adopted. We were still not told what we were training for, or how long a period of training we were likely to have.

In view of the fact that the regiment was recruited from all arms and from all different types of unit, the necessity was recognized of starting off the training completely from scratch on the assumption that no one knew anything. Only in this way was it thought that we could build up a unit of a high and constant standard of individual efficiency. So for the first month, every man in the unit had to go through a second recruit’s training, and pass a test in all elementary subjects, before going on with the more advanced training.

Paddy then discussed in detail the new organization and the function of each sub-unit in it. Each of the three sections which made up a troop was further divided into two equal sub-sections, each under the command of a corporal, or lance sergeant. These sub-sections were again divided into three parties of specialists: the light machine gun (LMG) party, the rifle party, and the rifle bomber party, each of which comprised three men, armed with the appropriate weapons. It can be seen therefore, that each sub-section was, on paper, a highly efficient little fighting unit, capable of providing its own support in many of the usual situations that are met with in battle.

All the training was carried out on the shore, just short of the beach. Here, was a thin line of sand dunes and scrubby country which separated the cultivated land from the beach itself. Through this rough land ran the coast railway. It proved to be ideal training country, for it afforded ample cover, and the sand-dunes formed natural butts for firing practice. Also it was only five minutes march from the camp.

We were kept busy for the first month at Azzib, getting ourselves fit and hardened up for whatever was before us, and making sure that everyone had the most complete basic training that was possible, before we turned to the more specialized forms of training. Many demonstrations were arranged, experiments were tried with equipment and loads to be carried, and also with lightweight nourishing rations. Gradually there evolved a complete scale of arms, ammunition, rations and equipment to be carried by each sub-unit, in such a manner that every individual man was given a specific load to carry.

Raiding Forces Headquarters, was officially, the headquarters which controlled the Special Raiding Squadron and the Special Boat Section, both administratively and as far as the training was concerned, but it soon turned out in actual fact that we were pretty well independent of this rather superfluous organization. Paddy had made this a necessary condition for his taking command of the squadron. As far as Raiding Forces HQ were concerned, they might not have existed, for all the effect they had on our training or our life. All decisions rested solely with Paddy and it was he alone who controlled us.

During our first month at Azzib, Bill Fraser joined us again and also Sergeant Johnny Cooper who had been with Stirling’s party when he was captured, but who had made good his escape. Bill had been up with the Eighth Army at the time when they sent the New Zealand column to turn the southern flank of the Mareth Line. Johnny Cooper had had a very exciting time. After escaping from Stirling’s party he and Mike Sadler, another sergeant, walked to the First Army lines. They were completely unarmed, and according to them, their most frightening experience was when they were attacked and stoned by some marauding Arabs who had the intention of killing them and robbing them. They either ran or bluffed their way out of this uncomfortable situation, and it was with some surprise and considerable distrust that the American outposts of the First Army saw these two dishevelled and ragged creatures approaching their lines. It was only with difficulty that they believed their story, and then they were flown back to the Eighth Army and thoroughly questioned. Mike Sadler was an expert navigator and it eventually transpired that the route he had taken in order to reach the First Army lines, was the route chosen for Freyberg’s mobile column, which so successfully turned the flank of the Mareth Line, and joined up with the First Army.

During this initial elementary training I was given ample opportunity to get to know my section and supervise their training. In this I was ably assisted by my three senior NCOs. Sergeant Andy Storey my section sergeant, ex-Scots Guards and very much the solider, was a hard-headed Yorkshire man, slow but infinitely sound – nothing could perturb him.

Corporal Bill McNinch, my leading sub-section commander, was the direct opposite. Worshipped by the men, he was the humourist of the section. He had a violent character of his own but none could get more out of the men than he, when he so wished.

My second sub-section commander Corporal Bill Mitchell was an NCO who had been under me when I first joined the unit in Syria. A shrewd leader and excellent soldier, Bill Mitchell proved to be one of my most loyal NCOs, and he remained with me right until the end of the war. All three of these NCOs had been proved in action and indeed were veterans of several operations, a fact which was of invaluable assistance to me in my own green and untried state.

After about a month of abnormally hard work it was considered that a satisfactory standard in the elementary training had been reached by every man in the unit, and we now turned to better things which were to have a more direct bearing on the task we were ultimately to be called upon to do. Side by side with the elementary training, steps had been taken to ensure that the men became as fit as was possible and capable of feats of endurance more exacting than any which the normal soldier was called upon to do. So the first item on the programme of the advanced training was to test the fitness of the men by making them march under conditions approximating to those of war, from the shores of Lake Tiberias, which was 600ft below sea level, over the coastal hills and back to our camp, which was situated on the coast. The distance was about 45 miles and we were to do the march in as short a time as possible.

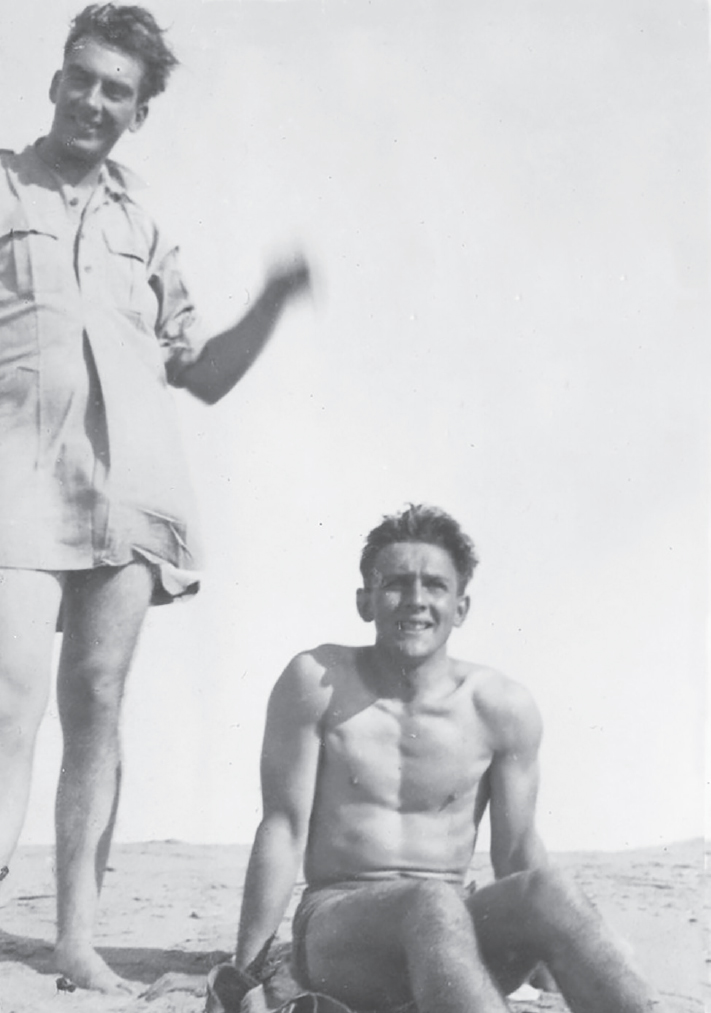

Alec Muirhead and Peter Davis, Azzib, May 1943.

Sandy Wilson, Jerusalem, March–June 1943.

This rather violent and unpleasant form of training was entered upon in a competitive spirit, for each of the three troops did it independently. No.3 Troop was the first to do it and, judging from their results, it seemed a formidable endurance test indeed. Out of a troop of about sixty, only eight men succeeded in completing the course. Apparently they had decided to march in the heat of the day with the result that they were fainting and passing out like flies under the glare of that summer sun. No.1 Troop fared little better, even though the majority of the troop completed the march, for they managed to take the wrong turning, and march for miles off their course before they realized their mistake. As a result they took nearly forty-eight hours to get back to camp.

And then it was our turn, and very apprehensive we were after examining the mediocre results of the other two troops. We had the advantage of course, of learning by their mistakes, and we certainly did not go out with any false ideas about what we were going to have to do. We left camp by truck early one morning and arrived at the starting point close on midday. The weather was typical of the Palestine summer, blazing hot, without a cloud in the sky, and throwing up a brilliant glare from the chalky white road. But while we were in the trucks, we were tolerably comfortable, for the breeze of our motion served to keep us cool.

Not until we got down from the trucks at Tiberias, did we fully realize how hot it was going to be. Our starting point was 600ft below sea level, and of course not a breath of wind was able to reach down into the depression in which we were. It was a stifling, sticky heat that left us feeling limp and clammy and made our heavy packs seem double their weight. And so we set off, hoping to cover as much ground as possible, before people started to tire or feel the effects of the sun.

Little need be said about the first part of that march, as it was so hot that it was as much as we could do to keep the sweat out of our eyes, to shift from time to time the heavy pack which, every few minutes, became stuck to the shoulders, and to fix our eyes firmly on the centre of the back of the man in front, or on the ground a bare yard in front of our feet. Tony’s section took the lead and we followed by sections in single file. We kept climbing all the way, along a narrow path which ran through thick corn fields. As soon as we reached one crest another one spread itself before us. Amid muttered curses we plodded on mechanically, sullen in the realization that our ordeal was only just beginning.

Eventually we came to a crest and to our joy found that the ground ahead actually started to drop. We descended steeply until we reached a small stream whose valley we followed as it wound up a hill. What a relief to our eyes was the high vegetation and the clear cool water, but the temptation which this offered soon added to our torments. We would have given anything to have been able to plunge right into it and drink our fill. But it was useless thinking along those lines, for strict orders had been given beforehand that no water was to be drunk until the word was given by the troop commander. The sight of this water so near and yet so unobtainable, only served to aggravate our thirst, but we were at least able to derive some comfort from it, by dipping our handkerchiefs into it, and tying them round our heads. But this, needless to say, only afforded relief for a few minutes.

Meanwhile the sun had been steadily rising and was now directly overhead, from where it beat down mercilessly upon us cruelly and inescapably. By now everyone had some sort of protection for his neck in the shape of a handkerchief or the canvas neck shield with which we had been issued. By about one o’clock the column was subjected to various short halts through some man passing out from the heat, and we all had to wait until arrangements had been made for his disposal. These halts became more and more frequent until about nine had succumbed. When three went down together, Harry very wisely decided that it was no good continuing further under these conditions and gave orders that we should rest until evening.

This order did not need to be repeated to be obeyed, and everyone scrambled for a bush or shelf in the rocks which would give some sort of shelter from the sun. We were allowed a short drink and then made ourselves comfortable and, despite the flies which proved to be an absolute menace, dozed and rested until the shadows lengthened and the noises of the day grew quiet.

About six we set off again, having only covered about 8 miles in six hours. But now the marching was far more comfortable and everyone felt far more cheerful after the very necessary rest. We covered a further 6 miles without anything of interest occurring and then we noticed signs of habitation. The country became more enclosed, and we began to pass one or two Arabs, shuffling along in the direction we were going. In the distance could be heard the occasional bark of a dog and the shouts of a child. Soon we came to a village through which we passed. The track widened and then became a stony lane. At this point we were halted and fell out to prepare our evening meal.

The ‘Tiberias’ march, Palestine, April–May 1943. Training for the invasion of Sicily.

For the march, we were experimenting in rations which would give the maximum amount of sustenance and yet were to be extremely light and compact to carry. So Bob Merlot, our intelligence officer, had prepared for us a ration scale of his own devising which fitted into a cartridge bandolier and weighed next to nothing. The mainstay of these rations was oatmeal and we had been shown how to make out of this, porridge, cakes or biscuits, or how, when the occasion demanded, a handful of it could be eaten raw with good effect. In addition we had dried lentils, bacon (which we could eat raw), and of course the invariable and very essential tea, dried milk and sugar.

We had our meal in a romantic setting. The cooking was done in parties of three, for the rations were so designed that three could cook together with the mess tins and water at their disposal. Quickly numerous little fires sprang up, and as the darkness deepened nothing could be seen but these orange glows with eerie shadows bending over them. The stream at whose edge we sat, reflected the scene: numerous Arabs passed with their donkeys, sheep or cattle and a brisk trade started in which eggs and bread were exchanged for cigarettes.

We were not hurried over our meal and, after we had eaten, were allowed to lie in the cool of the night, smoking and resting for a further half hour before we set off again. After about half a mile, the track we were following came out onto a metalled road, down which we turned. To make us more compact, we formed up from single file into threes, and with our boots ringing out clearly on the road, we swung along merrily enough.

We passed through another village, through the gardens of which we took a short cut, thereby probably waking up every living thing in the neighbourhood, judging by the noise which greeted us. From every garden a wretched cur would bark and howl, women and children scream and men shout. A short pause while Tony checked up on our route and then off again, through a small gate, down a narrow track, until we came onto another road at the foot of an enormous hill the top of which we could hardly see in the darkness. If at first we had fondly imagined that this road would lead us along the foot of the mountain, we were soon disillusioned, for on rounding a bend we found ourselves faced with a steep and seemingly interminable climb.

We climbed for over two hours up that cursed mountain, with the road winding ahead of us like a silver ribbon, zig-zagging its way in a series of sharp hairpin bends into the moon-softened darkness. After about an hour of this, the climb began to tell on us; the light-hearted chaff quietened, footsteps began to drag and the pace became noticeably slower. But these dangerous symptoms were not permitted to last for long, for McNinch, one of my corporals and always the man in an emergency, quickly started up a song. The rest of the section were not long in joining in, and from then until dawn the men were singing without a single break. It really was a magnificent performance. The other sections, not to be outdone by McNinch’s choir, started up in rivalry and for the rest of that night we were swinging along that road, eating up the miles in a very creditable fashion.

We covered over 20 miles that night, all of which were along the road. After we had reached the top of the first crest, the road was seldom level, and we had to spend the rest of that night’s march ascending and descending the slopes of this coastal range of hills. Eventually it grew lighter in the east, and we were halted close by a large Palestine police barracks, where we were able to wash the dust and grime from our bodies, and tend our blistered and lacerated feet. We had completed 32 miles in eighteen hours. Surprisingly few had dropped out, either through heat or foot trouble, and we were now only five or six short of our original strength. But although we had only about 15 more miles to do, it was clear that this last part of the journey was going to be the most difficult, for by this time, most of the men’s feet were in a very sorry condition, and there were few of us still able to walk normally. Also we had to put in an attack on an old ruined castle which lay on our route, and which was to be defended by some of the permanent camp staff who were to be transported there, in readiness for us.

We were allowed to breakfast in comfort. We had previously washed and cleaned ourselves up and changed our socks, and felt considerably refreshed. Oatmeal porridge, followed by boiled bacon and lentils, proved to be a very nourishing meal. We moved off again after a halt lasting an hour and a half. This time, it was the turn of my section to take the lead, and it was not long before we sighted the ‘enemy’ fortress nestling among the shrubs at the head of a deep gorge.

The attack was, of course, a complete farce. We made very little effort to take cover, as by that time, we were past caring about what the defenders or umpires would think of our assault. All that we could think about was our tiredness and our aching and smarting feet, and in consequence felt in no mood to play soldiers with members of the camp staff who had spent a comfortable night in bed and who had been taken to their position by transport.

But we need not have worried ourselves, or even tried to make the slightest show of the attack, for we soon found the place to be deserted and we were able to enter the castle without seeing a soul. We stopped there for about fifteen minutes for a rest and a smoke, and then pushed off on the final stage of the march, after scribbling a few rude notes on the walls of the castle for the benefit of the defenders, in case they should condescend to turn up later. We found out when we got to camp that the defenders had indeed been sent out but they never dreamed that we would reach the castle so soon. So we arrived at the objective several hours before the defenders, which saved both us and them a lot of trouble.

The first seven of the remaining 10 miles was along the side of a small fast flowing stream which in the course of centuries had worn a deep gorge for itself, and which wound below grim and rugged cliffs of black rock, rising up vertically on either side. At first there was a sort of path along the side of the stream but presently this disappeared and it was found that the easiest route to follow was along the river bed itself, which was not more than a few inches deep. What a wonderful relief it was at first to be able to cool our burning feet in the ice-cold water. The men’s spirits revived; they started splashing and larking about. Often someone would unwittingly step into a hole in the water, the depth suddenly increasing from about 12ins to around 5ft, much to the confusion of the involuntary swimmer! And then someone would slip and lose his balance and fall headlong into the water, amid the laughter of his fellows.

Thus although we were by now extremely tired, this was the most pleasant part of the whole march. The gorge was so steep that we were able to walk in the shade almost the whole way, while the cool water rushing past our feet was most refreshing. When we came to a spot where the river formed a natural deep pool, we were halted and those who wished to were given the chance of a swim, whilst the remainder rested on the bank and looked on, barracking and hurling cheerful insults at the bathers. Many of us welcomed this opportunity to examine our feet and change our socks, for it had not taken us long to discover that walking in the water as we had been doing for the last 4 or 5 miles, was the worst thing we could have done. The water had made the feet go completely soft to such an extent that it felt as though the very arches had dropped. In the limited time at our disposal, we patched up our feet as best we could, wishing fervently that the whole wretched exercise were over.

Peter Davis, Azzib, May 1943.

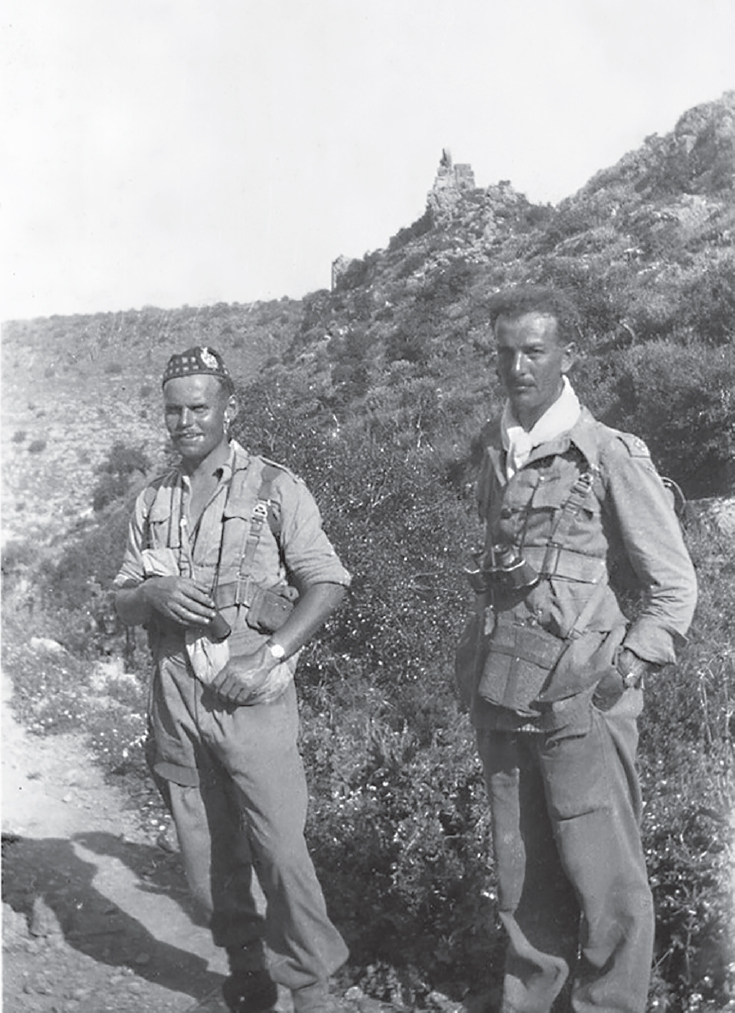

Derrick Harrison (left) and Alec Muirhead, Palestine, March–June 1943.

Those last 3 miles were infinitely the worst. When we eventually emerged from the gorge, it was to see before us the broad, flat plain which separated the range of hills over which we had just passed from the coast; and there, shimmering in the heat haze, a cluster of red buildings could clearly be seen. The end of our march was in sight for those buildings, which looked as though they were only a few hundred yards away, but which were in reality the best part of 3 miles from us, were our camp.

But now it was really hot and the majority of us had ‘had it’. Out in that open plain, we were at the mercy of the pitiless sun. Our feet had been so softened by their immersion in the stream, that every stone, every small unevenness in the ground over which we passed, made itself felt in all too painful a fashion. We followed a very narrow path through the standing corn, which was high enough to prevent us from seeing where we were treading. We were thus unable to avoid the numerous pebbles and larger stones, with which our way was strewn, and which served to aggravate all the more the very tender condition of our feet. The gay chatter of earlier in the morning had by this time died away and we plodded on in sullen, tortured silence, scarcely able to keep tears of exhaustion from our eyes, so great was our fatigue.

But all things come to an end, even unpleasant ones, and at 1.30, we found ourselves, to our intense relief, ascending the small slope on the top of which our camp was situated. We were, at this point, very spread out and nearly all were limping badly. But Harry decided to show the rest of the regiment that we thought nothing of the little march we had just completed, and passed the word back calling for a final supreme effort. The order to slope arms was given and we formed up into threes. As soon as we reached the tarmac road of the camp, at which point our steps could be heard plainly ringing out on the hard surface, everyone fell into step and we swung into camp as though we had only been a few miles. In some remarkable fashion everyone’s limp had disappeared and the troop must have been an impressive sight. We had reason to feel pleased with ourselves, for we had covered a distance of 48 miles over very rough and difficult country, and in the middle of the Palestine summer, in just over twenty-six hours.

The Tiberias march was a foretaste of the seriousness of our training and the strenuous days that were to follow. But I had the good fortune to be granted a little holiday from all this exertion. Bob Merlot, Sandy Wilson and I, together with a dozen men, were sent to Jerusalem to attend the Grant-Taylor revolver course. Bob Merlot, the unit intelligence officer, was one of the most perfect gentlemen I have ever met. A model of patience and tolerance, he was friendly to everyone, and the way he looked after our small party during that course at Jerusalem was typical of his kindly, easy-going but shrewd nature. The men worshipped him and would make every effort to abide by his wishes and not let him down. Bob was considerably older than us all – in fact, he had been a pilot in the last war – but to look at him you would never notice his age. In fact he was more capable of enduring hardship and pain than most of us and was more than able to do anything the regiment did.

Sandy Wilson was the quiet dreamy type with many hidden depths, but when you came to know him, you realized that there was a lot hidden beneath that gauche, shy and clumsy exterior. Poor old Sandy’s clumsiness was the watchword of the officers’ mess. He was extremely tall and possessed the largest pair of feet that I have ever seen. It may have been because of their very size, but at any rate, Sandy seemed to have no control over his feet whatever, and if he could put them into anything, he would. The result of all this was that whenever he entered the mess, people would make a rush for their glasses to bring them to a place of safety, before Sandy got near, and often the quiet of the evening was interrupted rudely by angry shouts of, ‘Oh Sandy!’ which was just an indication that Sandy had done it again. This was a most unfortunate characteristic for he had a heart of gold and was never ruffled even by the frequent and general expressions of disgust at his clumsiness. He would just give his quiet smile, a polite apology, and then promptly walk on and knock over someone else’s glass, or step on someone else’s toe.

We often found our way into the cabaret bar known as the ‘Queen’s’, which was situated in the main street. Bob, who was Belgian by birth, was attracted to this place because it had a girl crooner who was also Belgian, and the first night he came in, she took one look at him, and then came straight up and asked if he were Belgian! Thereafter, we found ourselves there practically every night.

The men from our regiment, who were also attending the course, were often at this place too drinking up their credits just as fast as they could in the limited time at their disposal.

One evening, only extreme good fortune prevented rather an ugly and unfortunate incident from taking place. Sturmey, one of the men, had had far too much to drink and was in a decidedly aggressive mood. In looking around for a suitable opponent, he picked on a young major who was looking very smart indeed, in a beautifully tailored cavalry uniform. He had a string of medals up, including the MC. But the bone of contention was apparently, a parachute wings on the major’s arm, which admittedly were of a design that none of us had seen before. Sturmey marched straight up to this officer’s table and accused him of being an imposter. Of course, then, the fat was in the fire with a vengeance. The major had the MPs called up and handed the very aggressive Sturmey into their tender charge. Still persisting in his accusation, Sturmey was marched off to spend the night in the guardroom, while Bob, Sandy and I vainly flapped around trying to soothe the irate major.

The next morning we were all amazed to see Sturmey turn up for parade, for we had thought he would certainly be up for court-martial. And so he would have been without the slightest doubt, were it not for the stroke of luck that despite the fact that his accusations were made solely through a surfeit of alcohol, the military police chose to look into them and have a private check on the major’s identity. By some extraordinary coincidence, which was fortunate for Sturmey, they discovered that he was in fact an imposter, being some lieutenant in a base job who wanted to look big. He had no right to wear either parachute wings or the MC and other ribbons. We left shortly after that narrow escape without any more of the men getting into trouble although this was due more to the leniency of the Military and Palestine Police whom we had come to know pretty well while attending the course at their barracks, than to any particular restraint on the part of the men themselves.

We found the camp to be humming with activity on our arrival. The main cause for excitement lay in the fact that during our absence the regiment had been visited, inspected and addressed by General Dempsey of whom we knew nothing beyond the fact that he was in command of some corps or other somewhere. General Dempsey had watched our training with the greatest of interest, then called the regiment together and for the first time since we started this training had given us some sort of indication of what we were training for. Apparently our regiment was to be under his personal command in some operation to take place at an undivulged, but not far distant date. Our role was to land in the first wave of the assault by landing craft, and to storm and capture a vital and probably very strongly defended coastal gun battery. The general made no bones about the importance of our task and even told us that the whole success or failure of the operation under his command might depend entirely on our own individual success.

Cliff climbing training, Palestine, April–May 1943.

Training was speeded up from then on, and the form it now took gave us several indications of what the job we were going to do would be like. For instance every night from then on, almost without exception, was spent in practising cliff climbing in total darkness, and perfecting the drill of this to such a degree that the whole operation could be carried out from start to finish, without a word being spoken.

Each troop would then be given a certain area in which to practise while Paddy would be roaming about up on top ready to come down in fury on any section which was doing it wrong. Many amusing incidents used to occur during these exercises, one of which I remember all too clearly. As part of our equipment each section was provided with two lengths of rope fitted with a toggle attachment so that they could be joined together or looped around a rock. The officer and his batman were the first to climb the cliff, each carrying his rope, and when they had reached the top they would lower their ropes and the rest of the section would climb up one by one, and then take up a defensive position immediately they arrived at the top. It can be understood therefore, that for the first part of the operation, until sufficient men had been brought to the top to provide satisfactory protection, the whole strain of holding the ropes firm rested with the officer and his batman. Percival my batman/runner was not much heavier than me, but in addition he was a stock joke with the section because he would get into a violent flap at any situation.

One night we climbed a cliff as usual and took up our positions to take the strain of the next to climb the rope. Unfortunately in the particular spot where we were, no suitable projections in the surface of the rock were to be found, round which we could hook our ropes, and so we had to take the whole weight of the climber without assistance. We just managed for the first one or two and then we naturally began to feel rather tired.

All of a sudden, Percival found himself slipping. An almighty shriek of ‘SIR! Save me! Save me! Help! Help!’ rent the air, with scarcely any attempt at a whisper, so great was Percival’s panic. I looked round to see him slowly slipping down the cliffside and of course could not do anything to help him, as I had my own rope to deal with, up which someone was in the process of clambering. But I and most of the others nearby could not fail to see the humour of the situation wherein such a melodramatic cry should be raised in a serious exercise in which no word was meant to be spoken. I found myself so doubled up with laughter that I could scarcely hold my own rope and almost suffered the same fate as Percival. McNinch, who had just come up, quickly rushed to give Percival a hand and to restore the situation, but it was a long time before our amusement died out, and before we were able to regard the exercise with any degree of seriousness.

Harry Poat (left) and Phil Gunn, Palestine, April–May 1943.

Great amusement, principally among the officers, was caused by the horses and mules which we had with us for training. In theory it was decided that we might, on the coming operation, find ourselves without transport and therefore, if we could capture any enemy horses or mules, all the better. So we obtained from the RASC two horses and four mules, ostensibly to teach the men which end of the animal was which, and to learn how to manage them to some small degree. For obvious reasons the mules did not arouse nearly so much interest as the horses. But John Tonkin showed a marked attraction to these animals based, I believe on some experience of them in Syria, and he and Ted Lepine and Mick Gurmin appointed themselves their keepers. They even formed such an attachment for them that they moved out of their tent and went to live in part of the stables which had been boarded off into a kind of hut. Richard Lea was the horse-riding enthusiast and I think it was at his instigation, that Franco (very ex-cavalry and all that) was prevailed upon to give certain of the officers riding lessons each morning before breakfast. (Not that it takes much prevailing upon to give an ex-cavalry officer something to do with horses again!). So any interested spectator could see certain officers dodging PT by riding sedately round in a circle obeying Franco’s very cavalry words of command to t-r-r-o-o-o-t, or c-a-n-t-e-r.

Richard Lea, who by that time was training officer, could not keep away from these horses and used to take them out on every possible occasion on the very plausible excuse that he wished to organize some training exercise, until the day when No.2 Troop did their Tiberias march. He thought this would be a good chance to take out a horse, to observe how the troops were bearing up under their ordeal, and so set out to find us. But we were so much ahead of schedule that he completely failed to contact us, and moreover, to his dismay, he found that the going was so rough that he had to dismount. And so after spending the best part of the day trudging about the mountains, dragging an unwilling horse behind him, he had to return to camp almost as tired as we were and pretty fed up with horses in general. From that day on, Richard’s interest in horses showed a marked decline!

By the middle of May there was a definite ‘operational’ feeling in the air, a feeling of suspense and tension. One day all three troops were independently given their first briefing. A sketch map of our actual objective was drawn for us and it was intended that we should learn every detail of this by heart. In addition, we had to learn the exact route we and the other troops would take. The initial plan was roughly as follows. No.1 and No.2 troops were to land on the south coast of a promontory about 200 to 300 yards west of our objective, a gun battery of three, or possibly four, heavy guns. No.1 Troop was to make straight for the camp buildings, and systematically clear them out while No.2 Troop was to make a detour around the western side of the target and come onto the guns from the north, from where they would put in their assault. Meanwhile No.3 Troop had been landed about half a mile further still to the west and was to cut the only road leading to the battery and occupy two farms which held strategic positions in that region.

These were the first orders we received about the coming operation. From then on, we practised our respective roles, day in and day out. Whenever we went out on a night exercise, climbing cliffs, or some similar occupation, to attack a prescribed imaginary target, No.1 Troop would always go straight in while we would make the detour and assault under cover from No.1 Troop’s fire-power. This procedure was so ingrained into us that it became second nature, and we learned only to make an assault when covered by a very healthy amount of fire-power from another subunit. This principle was even applied right down to section, sub-section and party training and a kind of battle drill was evolved, which we were to practise day after day, so that in the end every man would be trained automatically to carry out a certain reaction at any given situation.

Along with this battle drill, great attention was paid to our marksmanship, and towards the end we spent nearly the whole time firing with live ammunition, and in combining this with the battle drill we had just learned. Much time was spent on range practices at first, but this rather artificial form of training was soon substituted by one which proved to be far more useful. Mere accuracy, it was considered, was not good enough by itself but had to be combined with speed to be really effective, and so the system was adopted of competitive shooting by parties at tin plates. A party would vie with another in knocking down its six plates before the other. This not only encouraged the desired combination of speed with accuracy, but also made each man give some thought to the most effective distribution of his fire. It was a most enjoyable and profitable form of training, causing any amount of cheerful rivalry.

The next stage in our practical training was combining our battle drill with using live ammunition. One night, right towards the end, the whole squadron went out practising this movement with live ammunition and using tracer to direct their fire. The effect was striking. Fire seemed to be pouring onto the target from all directions until the whole sand hill seemed to be aflame. The tracer bullets would ricochet off the hilltop and go shooting straight up into the air like miniature rockets. Were it not for the seriousness underlying the whole procedure, one might compare the effect to Blackpool Illuminations. At the height of this exhibition one of our fighter aircraft chose to fly around just above, curious at what was going on, until all of a sudden the ricochets rising straight into the air must have given it a fright for it replied with a burst of cannon fire into the sea and made off smartly. Later that evening the squadron was officially reprimanded for firing at friendly aircraft!

To Alec Muirhead was given the task of training an efficient 3-inch mortar section. Alec had never seen a mortar before, but this ignorance on his part was put to good effect, for he trained his section entirely along his own lines and in complete defiance of the training manual. As a result of his conscientious experimenting, he was able to mount the mortar and get off his first round with considerable accuracy within eighteen seconds. Of course his lack of acquaintance with the subject did not always stand him in good stead especially on the occasion when, through some miscalculating, he inadvertently directed his crew to fire five bombs rapid, straight down onto his OP position which was about 500 yards in front of the actual mortar. As soon as he heard the first bomb in the air he knew he had done something wrong and immediately realized what it was. The awful suspense of knowing that there were four bombs still to come, any one of which might be a direct hit on him, can well be imagined. He was very lucky indeed to get away with only a cut on the back of the head from a piece of shrapnel.

The manner in which Alec’s mortar crew had been recruited was rather amusing. As soon as it had been decided to use 3-inch mortars, a message had been sent off to the Infantry Base Depot at Geneifa, asking for forty trained mortar men, as we thought there would not be time enough to train a crew from scratch. The men arrived all right, but it did not take long for Alec to find out that very few of them had ever seen a mortar in their lives before. It seems that in typical fashion the message had got muddled at some point during the course of its journey, so that the IBD thought that the men were wanted to go on a mortar course. So these poor lads all arrived thinking they were going on a nice cushy mortar course, and were instead launched straight away into a programme of intensive operational training. It says something for them that nearly every one of them turned out well, and were only too keen to be embodied in the regiment once they had come to know us and the work we were to do.

With long night schemes on a full-scale model of the target area, our training at Azzib ended. What had been a motley and relatively untrained force only two months previously had now reached such a peak of trained efficiency that there were, I am sure, very few fighting units in the British or German army to beat them. They had mastered a thorough knowledge of their own and of the enemy’s weapons. Their average marksmanship was extremely high, and combined with this accuracy, a very creditable speed. They had learnt to work as a smoothly running machine from the whole squadron, down to the smallest sub-unit, and each man knew how to react to any given eventuality. In addition, they had grown accustomed to working under fire.

Everything down to the slightest detail of the load each man was to carry had been worked out and tested and the regiment was drilled into a state of perfection. Above all, they were as physically fit as any human beings could possibly be. Their offensive spirit, or ‘morale’ as it is commonly called, was excellent. Not out of patriotic fervour, but solely out of the lust for excitement and the supreme confidence they had in their own capabilities, did these men long for the time when they could show that all the trouble they had been taking during this gruelling training had been worthwhile, and the knowledge that they were completely equipped and trained for the fight made them all the more keen to meet it. As a fighting body they were perfect.

We left Azzib for an unknown destination at dawn on the morning of 6 June 1943. On the principal of ‘let us eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow we may die’ there was a mad party that night in which both officers and men attempted to consume every drop of liquor to be found both in the camp itself and in its immediate surroundings. Many were the Jeeps ‘misappropriated’ and taken out for a final binge in Haifa, many alas, were the Jeeps found deep in roadside ditches at the break of dawn, and many were the recumbent bodies that were littering the mess shortly before we were due to parade about 3.30am. It still amazes me how, when the train steamed out of the station no one had been left behind.

It was still dark when the transport took us all to the station. Dawn was just lighting the horizon when we climbed into our allotted and very crowded cattle trucks which were to take us slowly and painfully along the first stage of our journey to Haifa. None of us had the slightest idea where we were going. Many of us, in the condition in which we were at the time, were too merry to care. All we knew was that sometime soon, within a matter of weeks, if not days, we would be given the chance to match our strength against that of the enemy. And of the ultimate result, none of us had the slightest doubts.