THERE IS A CLEAR DISTINCTION in the Western world between the sacred and the profane. There is also a continuing debate about the role of religion in a secular society. I doubt whether such a debate could have taken pace in prehistory, because in those far-off times the distinction between the daily and the spiritual worlds was far from clear-cut. As we have seen, the domain of the ancestors frequently impinged on daily life, and at several levels. But people did have to lead their ordinary lives and cope with the routines of the farming and domestic year, and that would have been the backdrop against which their spiritual activities took place.

Unfortunately, it’s too easy to view the remarkable religious sophistication of Bronze Age communities in isolation, as a phenomenon in its own right. This is highly misleading. I am convinced that such a lack of contextual balance is the main factor behind the growth of the semi-mystical nonsense that is written about the Celts, the Druids, Atlantis and so forth. In reality, the mundane world of the Bronze Age was as rich and complex as its foil, the realm of ideology. Both sides of life contributed equally to what was rapidly becoming an emerging civilisation.

It took three years for us to discover the remains of our first Bronze Age roundhouse at Fengate, back in 1974. I now want to retrace my steps to find out more about the people who lived in that house. We’ve discussed religion, landscapes and even social organisation at some length, but we haven’t said very much about daily life as it would have been led by ordinary folk when they weren’t constructing barrows, henges and the rest. I’ll use that first Bronze Age house as a peg on which to hang the objects and events of the everyday world three to four thousand years ago. Before I go any further, I must first justify my use of the term roundhouse to describe the buildings which are so important to our story.

One often hears people who should know better talking about such houses, and their modern African equivalents, as huts. To my mind, a hut is something knocked together in a hurry and without a great deal of care and consideration. Vegetable gardens and allotments are the ideal habitat of the hut. As buildings go, I am sure they have many tales to tell, but they don’t contain much information about the way people actually lived. Houses, on the other hand, are places where families of humans dwell. A house says much about the people who use it. It speaks of their pride in themselves, of their wealth, or lack of it, their status within society and their ability to organise their lives. It is far more than just a building.

The Bronze Age houses I have excavated have mostly been round. Rectangular buildings from the period are known in Britain, but they are rare and may well have been communal – perhaps the equivalent of a village hall. On the Continental mainland, on the other hand, rectangular houses were the rule throughout later prehistory, from the Neolithic period right through to Roman times. In Britain and Ireland, Neolithic houses may have been rectangular (they are so rare as to make generalisation difficult), but from the start of the Bronze Age at least, they were almost invariably round, or round-ish.

The size of these prehistoric roundhouses varied, depending on when and where they were built, but most had diameters ranging from about five to ten metres.* There are notable exceptions. Two Early Iron Age roundhouses have been excavated at Cow Down in Wiltshire and Pimperne Down in Dorset. These were truly staggering structures, whose diameter was no less than fifteen metres.

Roundhouses are superb buildings, and I have always been astonished that they were not used more widely on the Continent in prehistory. The shape is inherently stable and sheds the wind well. During the great hurricane that struck southern England in October 1989, I happened to be inside the reconstructed Bronze Age roundhouse that we had recently completed building. I remember standing at the door in my shirtsleeves watching while sheets of roofing material and other debris blew across my view. Behind me, the modern factories of Peterborough’s Eastern Industrial Area were being seriously damaged by the gales, but, snug inside the roundhouse, all was still and tranquil.

The strongest point in a conical roof is the apex. If the roofing material is lightweight, such as thatch, the entire weight of the roof can be supported on the walls and there is no need for a central post. In the case of very large buildings, such as those at Pimperne or Cow Down, the rafters may either sag or have to be joined, in which case the simplest thing to do is to erect one or more circles of internal roof-support posts, on which rests a continuous circular ring-beam. This ring-beam supports the rafters and helps hold the roof in place. But ideally the house should be about ten metres in diameter, in which case there is no need for posts inside the living area. When you walk into such a building, your immediate impression is of spaciousness. Above you is a high roof into which the light smoke from the central fire swirled. Up there, in the gloom of the roof space, the prehistoric inhabitants would have hung all sorts of good things: smoked hams, dried fish and eels, cheeses, game and other meats.

We built our first Bronze Age roundhouse in the archaeological park we laid out around the Flag Fen excavation in 1987. We also reconstructed the fields and droveway nearby, but not on the original site; instead we placed this reconstructed mini-landscape on land we had available out in Flag Fen, about half a mile to the east. The frame of the house was built of wood and the wall was formed of woven wattle smeared with clay daub. When we constructed the wall, we used thick coppiced hazel rods of about one to two inches diameter. These had to be woven around the wall posts, which were spaced at metre intervals, more or less. The difficult part came when the wattle was rammed or trodden down hard, to make a good tight weave. If the tips of the wall posts aren’t adequately buried, the accumulated outward pressure of successive layers of springy hazel rods can force them out of the ground. This accumulated outward pressure is particularly strong at the doorway, whose frame would have been held securely in place by a good stout lintel. The pressure generated by the woven wattle doubtless helps to account for the fact that most door posts were considerably larger than the other posts of the outer wall. After a few months hazel looses its springiness, but by this time the walls have ‘set’ into an extraordinarily strong and resilient structure.

The excavated archaeological ‘footprint’ of our first Bronze Age house was slight – just a double circle of post-holes, two slightly larger front-door posts and a continuous shallow ring-gully around the outside. The inner circle of posts supported the centre of the roof rafters. The posts of the outer circle served a dual purpose. They provided pillars, around which the wattle skeleton of the wall was woven, and they also supported the roof rafters.

The ring-gully outside the walls was a very shallow ditch (about thirty centimetres, or one foot, deep) that had been cut into the ground surface about half a metre outside the outer wall. It was positioned directly below the wide eaves that kept the mud-based daub walls dry. Properly made daub, well mixed with plenty of straw and cow dung, will stand up to rain blown onto it in a sharp shower, but it won’t tolerate continuous wetness. So the shallow gully below the eaves – known as the eaves-drip gully – was in effect the gutter that took rain from off the roof.

Hundreds of prehistoric eaves-drip gullies have been discovered in Britain, and we found ours worked well. Not only did it prevent splashing when water from the roof hit the ground, it also markedly reduced rising damp around the base of the walls. Normally the gullies stood on their own; they didn’t need to drain into a ditch or soak away. But in this instance the original builders must have hit a snag with ground drainage, so the gully was given a short extension, which drained it into a nearby droveway side-ditch. Archaeologically, this was a great stroke of luck for us.

I remember thinking, shortly after we had exposed the slightly darker mark of the ring-gully on the surface of the gravel, how considerate it was of the Bronze Age house-builders to link the gully to the droveway drainage-ditch in this fashion. Without this link, we might have found it difficult to prove beyond all reasonable doubt that the small roundhouse – the diameter of its wall was about eight metres – did indeed belong with the field system. But an actual physical link proved their association beyond any doubt.

Later the following season we found four other roundhouses. These buildings were on their own, tucked away in the corners of fields or, in one case, within a small ditched yard. Sometimes we found a formless scatter of post-holes, perhaps of an outbuilding of some sort – possibly a dry wood or hay store – but we never found more than one farmhouse together. This would suggest that the people who farmed the fields lived in harmony with one another and did not feel particularly threatened from outside; otherwise we might have found villages, with perhaps a stockade or earthwork around the perimeter, to act as a symbolic and practical defence. Unfortunately, however, I don’t think it was quite as simple as that. I don’t believe there was much aggression from people outside the region, although I do think there was a good deal of controlled aggression and social competition among the communities living in it. I suspect, too, that this controlled aggression formed an almost routine part of daily life – but only at certain times of the year.

Most acts of aggression can be deflected by providing a symbolic defence, which states in effect that this particular settlement is ours, and that any uninvited outsiders are unwelcome. In some societies the symbolic defence may encourage certain controlled types of small-scale raiding, in which, for example, cattle are rustled. This pattern of raiding only happens at times of the year, such as autumn, when crops and forage are safely gathered in and there is food enough for people to relax – and to think of things other than merely winning a livelihood from the ground.

Rustling is very commonly encountered in traditional societies where livestock are an important part of the local economy. It can be seen as a controlled form of social competition, between individual communities and even individual young men (doubtless to impress certain individuals of the opposite sex). It is most unlikely that older people took part in this rough-and-tumble, but I suggest that they would have tolerated, and even encouraged it. By the same token, prompt action would have been taken if things got out of hand and threatened social stability.

Something as necessarily ephemeral as rustling is difficult to prove archaeologically. Two young warriors gallop across fields and droves, brandishing spears and looking magnificent. Before the gaze of horrified onlookers, they steal a prize bull and ride into the sunset. How can that possibly leave an archaeological trace? I concede that it can’t leave a direct trace, but we can put together clues from other sources.

Neolithic and Bronze Age people were profoundly concerned with boundaries. They marked them with burial mounds, religious shrines to the ancestors and smaller-scale offerings of all sorts, including isolated burials. Boundaries are crucially important. Not just the big national ones, marked out by customs posts at border crossings; other boundaries are essential to the conduct of normal social life. We require them to ‘know where we stand’, in all senses of that phrase; without them we’re lost, socially, emotionally and possibly physically too.

So boundaries are a key part of our social geography. And they are as important today as they were four thousand years ago. A boundary only gains and retains its significance if it is repeatedly tested, and proved to hold. Prehistoric people couldn’t afford the modern luxury of wholesale slaughter, so frequent, smaller-scale, less bloody boundary infringements would keep the position and importance of current boundaries clear in people’s minds. Rustling raids would have served this purpose ideally. Doubtless there would be formal, possibly semi-ritualised, apologies between the elders of the various communities involved. These meetings probably took place on a subsequent occasion, after each raid. They may well have happened at the barrows, major droveways and shrines that marked the actual boundaries. I can perhaps put it another way: during a raid, the boundary had been honoured in the breach; in the consequent meeting it was honoured in the observance.

Semi-formalised rustling of this sort was also an opportunity for young men to show off their fighting skills and to brandish their finest weapons, which in turn were a symbol of their owners’ status within society. I think it very improbable that a rich Bronze Age father would let his sons go on a rustling raid with second-rate weapons, as things not directly associated with rustling – most notably the family’s prestige – would also be at stake.

The bronze weapons of the period are very interesting. Large-bladed thrusting spears were used throughout the Bronze Age, as were daggers and shorter swords, known as dirks. There were no swords in the Early Bronze Age, as the technology of casting them took some time to master. But around 1400 BC we see the appearance of long (up to half a metre), thin and pointed swords; these were thrusting weapons, known as rapiers. As weapons went, they weren’t very robust and there were problems in attaching the blade to the hilt. I doubt whether they would have stood up to the rigours of a prolonged campaign, which makes me think their use, in anger, would have been short. More likely than not – and this probably applies to most Bronze Age weaponry – their main use was as an object to brandish fiercely on raids. They would also have been worn in peace, as personal symbols of rank, power and authority.

It’s interesting to note that Middle Bronze Age rapiers and their shorter cousins, dirks, are very commonly found in and around the Fens. In recent years my own research in the Fengate/Flag Fen region has revealed three. The Fens in this period were very much given over to livestock-rearing, and it is hard not to see these weapons as having been used on rustling raids.

The widespread introduction of riding, and of horse-borne warriors, was a major change which took place in the Later Bronze Age. I hesitate to use the word ‘cavalry’, with its suggestion of organised fighting; I think it far more probable that the first horse-borne warriors spent much of their time posing in warlike attitudes, either to encourage their friends or to intimidate their enemies. It’s in the Later Bronze Age – in round terms after 1300 BC – that we encounter the first harness fittings and the earliest slashing swords. These are weapons whose weight lies towards the tip of the blade, and which were intended to cut downwards, like the cavalryman’s sabre. Sometimes the scabbards of these swords were fitted with so-called winged chapes. The chape is the metal bit at the tip of the scabbard which prevents the sword from cutting its way out when sheaved. Winged chapes were cast with pointed, wing-shaped protrusions which could be held steady beneath the rider’s heel, thereby allowing him to draw the sword single-handed across his chest while his other hand controlled the reins.

The first shields also appeared at about this time. They were carried on the forearm, and were very much smaller than the long shields of medieval mounted knights. Most were round, and less than a metre in diameter. The largest ones were made from beaten sheets of bronze and are extremely beautiful objects, decorated with concentric ridges, bosses and rivets. When highly polished and glinting in the sun, they would have looked magnificent. Unfortunately, however, they were useless.

During my final year at Cambridge John Coles, the lecturer involved with wetland archaeology who kept my interest in the subject alive, gave lectures on experimental archaeology. They were superb, and the best of them all was on Bronze Age shields. Using replicas, John showed how the thin beaten shields could be sliced through with a contemporary leaf-shaped slashing sword, like a carving knife passing through tinfoil. I still remember the startled expression on the face of the student holding the useless but beautiful shield.

John then carried out the same experiment, but this time using replica wooden and leather shields, known from peat-bog finds in Ireland. These proved wholly effective – which goes to show that appearances can be deceptive. It also leads us to the inevitable conclusion that the beautiful metal shields were not about actual fighting at all, but were probably made to be carried in processions and ceremonies. If they were about aggression it must have taken a more peaceful form, in which powerful men from great families competed with one another to see who could mount the most magnificent display.

A rapidly growing body of recent research has shown that Bronze Age fields similar to those found at Fengate are known at several locations across East Anglia. Although the fields at Fengate seem to have started somewhat earlier than the others, most came into existence at the close of the Early Bronze Age, around approximately 1500 BC, and continued in use through the Middle and Late Bronze Age, eventually being abandoned in the first half of the first millennium BC. Their demise, in other words, happened gradually during the initial centuries of the Iron Age, or the closing years of the Bronze Age. In nearly every instance that we know about in East Anglia, Bronze Age fields were laid out using the framework of an earlier landscape, which was defined and marked out by barrows, henges and other religious shrines placed at significant boundaries within and around the landscape.

It is sometimes said that the houses and settlements of the livestock farmers who used these fields were unenclosed or undefended; I am not so sure about that. Certainly there were no banks, walls, ditches or stockades surrounding the individual settlements, but that does not necessarily mean they were completely undefended. I am certain they were not open to any passing stranger who might feel inclined to take possession of them.

The boundaries of the land-holdings controlled by the individual farmsteads were very clearly marked out by droveways and large ditches. These in turn were reinforced by the ‘spiritual electric fence’ provided by barrows and other shrines that were repeatedly visited throughout the Bronze Age. As we have already seen, they were defended – or rather, they were watched over by the forces of the ancestors – but at a distance. It’s interesting to note that a symbolic, ritualised boundary of this sort only works if the people likely to breach it are familiar with the layout and ownership patterns of a particular landscape. It would be poor sport to trespass into another family’s land-holding if you weren’t really aware of where it began and ended. Again, this would suggest localised raids rather than longdistance military campaigns.

We only start to find physically defended or clearly delineated settlements within field systems at the very end of the Bronze Age. This suggests to me that the social control which maintained the individual components of the landscape was beginning to break down, for whatever reason. In the new conditions prevailing in the Early Iron Age people began to live together in larger, more nucleated communities. No longer were the spiritual boundaries out in the landscape adequate. Something closer to home and more obviously deterrent was required to keep unwelcome visitors at bay.

We learned a great deal from the reconstruction of that first Bronze Age house at Fengate. We used ash and oak timber cut from a local wood for the wall posts and rafters, cut wattle from ten-year-old stands of coppiced hazel, used reeds placed below a layer of turf for the roof, and plastered the wattle walls with daub. From other experimentally reconstructed prehistoric roundhouses we knew that it would be a great mistake to leave a chimney hole at the centre of the roof, as this had been found to work rather like a blast furnace: the central fire roared away, soon the roof was alight, and the house burned to the ground. We made many mistakes, but were glad we hadn’t made that one.

Without a central chimney, smoke filters out through the thatch and coats it with a thin layer of ash and carbon. This coating not only preserves the reed, it also helps to prevent water from being absorbed. But, of course, there is a down-side. If you burn wet, or even damp or freshly-felled wood, the smoke given off is far too dense to filter out through the roof. Soon everyone in the building has streaming eyes and the sound of coughing can be heard miles away. We also found that certain woods burn with less smoke than others. Dry, well-seasoned willow, for example, is a smokeless fuel. It’s inconceivable that they didn’t know these things in the Bronze Age – which is why I’m sure each household must have had a special building as a dry-wood store, where wood could be kept for at least a full year before being thrown on the fire.

We don’t know what medicines were routinely used, but many folk remedies are highly effective and have roots of unknown age. Willow bark contains high levels of aspirin, and can be chewed to ease the pain of toothache; it can also be heated up to make a very effective analgesic tea to cure headaches or hangovers. I suspect that the former would have been more common than the latter in the Bronze Age, because it is possible that the consumption of alcohol, perhaps in the form of mead or ale (beer made without hops), only took place during religious ceremonies. In many tribal societies the recreational use of alcohol is not allowed. It is seen as something special, to be appreciated in a special way and on special occasions. By the Iron Age, drinking had become a feature of life in high society, and by the dawn of the Roman period wealthy Iron Age Britons were importing wine from the Mediterranean in amphorae.

The Bronze Age saw the introduction of many things that we now take for granted. The wheel is perhaps the most obvious example. We don’t know when the very first wheel was introduced to Britain, but it was probably some time in the Early Bronze Age. The earliest wheel yet found in Britain is somewhat later, although still well within the Bronze Age, and I had the good fortune to be closely involved in its discovery.

It was found in 1994 at Flag Fen, where it seems to have been used simply as a short, flat piece of wood, thrown onto a damp piece of ground along with other wooden bits and pieces, to raise a pathway above the surrounding water. This probably happened between 1200 and 1300 BC, in the Middle Bronze Age. The piece of wood was crescentic and made from alder, a wet-loving tree that is fine-grained and naturally resistant to rot. The central plank and the other crescentic piece were missing, but wheels of this type, made in three parts, are not uncommon in Holland and Germany, and our wheel was almost identical to other tripartite wheels found on the Continent and in Britain and Ireland. In fact they are so similar, it’s tempting to suggest that the design had been got right. Clearly the wheels worked well, as they were made to the same pattern for centuries.

When we came to look at it more closely, we were struck by the wheel’s sophisticated construction. You might imagine that the simplest way to make a wheel is to saw a thin slice through a round log, Flintstones fashion. Unfortunately such a wheel might last for an hour or two, but soon it would split from the centre when it wobbled on its axle – wood splits very readily from the centre to the outside. Also, the outer sapwood which would have formed the wearing surface of this Flintstones-style wheel becomes brittle when it dries out. Besides, saws that could cut through large logs were not available until Roman times. All in all, such a wheel would not have been possible, let alone a success.

The Flag Fen wheel was cut from three hewn planks of alder which were held firmly together by two oak braces in dovetail slots, one on each face. The three planks would have flexed against themselves as the wheel revolved had they not been pinned in place by two snug-fitting ash dowels. Each type of wood used was the right one for the job, with the right properties of strength, workability and resilience. In its way the wheel was a miniature masterpiece. But there were two aspects of it that we found particularly remarkable and exciting.

The first, and perhaps least unexpected, was the discovery of two gravel pebbles that had been forced into the wheel by normal pressure on the road. At first glance there’s nothing remarkable about that – except that the wheel was found in soft, peaty alluvium which was entirely stoneless. During its life it must have run on a fairly hard road, probably surfaced with gravel. So, on the one hand we have – admittedly rather tenuous – evidence for made-up or surfaced roads, and on the other a firm indication that the wheel was a real one, as used in daily life. It was not something that was made to be thrown into a bog as a religious offering.

Strange as it may seem, offerings in bogs, ponds, lakes and rivers were a very common feature of the Bronze Age across most of Europe, from Italy to Scandinavia. Most finds of Bronze Age metalwork, for example, come from wet places, and it has been suggested, quite reasonably in my view, that these objects were not necessarily as strong or as well made as those that were in actual daily use. That cannot be said of our wheel. Two years previously at Flag Fen we had found half an oak axle that probably went with another wheel. It had been quite heavily worn; again, this suggests that it had seen regular use and was not a specially made religious offering.

I mentioned that the three original parts of the wheel were held in place by two dovetail-shaped oak braces, one on each side. These braces were cut from the outer part of a young oak tree, and a thin layer of bark still adhered to the surface in a few places. This is fascinating. The outer wood of a tree carries the sap, which, as lovers of maple syrup know, contains the sugars and other nutrients the tree requires in order to grow. As wood, it is almost as strong as heartwood, but it’s more flexible. This flexibility comes at a price, however. The sap soon dries out, and then the sapwood becomes brittle and prone to cracking. Being full of nutrients, it is also very prone to rot.

Do these weaknesses suggest ignorance on the part of the Bronze Age wheelwrights? I think not. In all other respects the design of the wheel is exemplary. They selected oak sapwood deliberately, knowing full well that it had a short use-life, but that it didn’t matter. Nowadays we’d say that this particular component of the wheel was expendable. It was, perhaps, the ancient equivalent of a modern shear bolt – a component designed to shear off and bring the machine to a sharp halt in order to prevent damage to other, more expensive parts. I would suggest that the sapwood laths were replaced every time the wheel was overhauled. The wheelwrights would not have been aware of it, but a new age, that of routine mechanical maintenance, had begun.

I don’t know why, but whenever I talk to people about the Flag Fen wheel they immediately assume that it was off a cart or farm wagon, as if the earliest wheels had to be large and crude. But those ultra-crude Flintstone wheels were part of their cartoon Stone Age car. Possibly without knowing it, the television animators had got it right. The diameter of the Flag Fen wheel is about nine hundred millimetres. That’s smaller than most bicycle wheels – hardly a farm cart. Examples of stouter wheels are known from the Continent, but this one was slender and lightly built. Maisie reckoned it was more likely to have been part of a Bronze Age governess cart, light trap, or even a wheelbarrow, than a farm wagon.

In 1997, three years after finding the wheel, we made another quite unexpected but altogether remarkable discovery. I was directing excavations in a gravel quarry on the edge of the Fens about five miles north of Peterborough. The site was in the Welland valley at the point where it opens out into the great Fen basin. As valleys go, it appeared almost identical to the lower Nene valley immediately to the south. It was flat, low-lying and richly strewn with prehistoric fields, farms and settlements. The quarry itself was actually below the water level of the modern river Welland, which flowed behind its high bank, well above our heads. Hence the name of the quarry, Welland Bank Quarry.

Like Fengate, Welland Bank was only a metre or two above sea level, and like Etton, four miles upstream, it was buried beneath thick layers of river-borne flood-clay alluvium. Like Flag Fen, the date of the site was Middle and Late Bronze Age. Beneath the alluvium was the preserved prehistoric topsoil, which was carefully removed with large machines under the close supervision of an archaeologist. I forget precisely who it was who spotted them first, but I remember the Site Supervisor, Mark Dymond, calling me across to have a look. And they were very odd indeed.

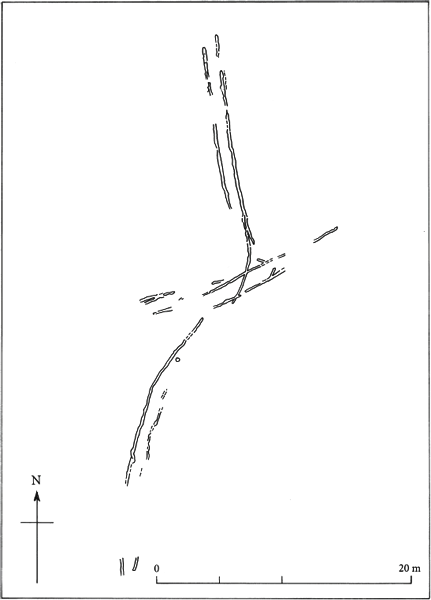

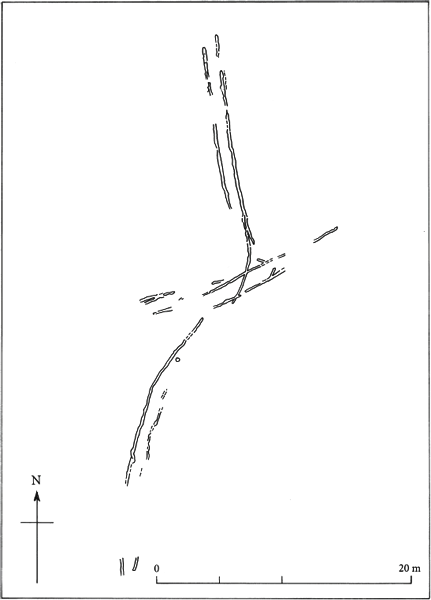

At first glance they looked like the marks left by a sledge dragged through deep mud. They had first appeared directly below the buried prehistoric topsoil when it had been stripped off by the digger, and consisted of two parallel grooves, filled with buried topsoil, that had been cut or squashed into the underlying gravel. They were quite distinct, but very shallow – no more than an inch or two deep, and about the same in width. They could be traced for about fifty metres, and at one point another, identical set of ruts crossed them.

When their full extent had been revealed, it was quite clear that they couldn’t possibly have been made by a sledge. They had to be wheel-ruts. In one place we could see where the vehicle had see-sawed to and fro, either when stuck or when turning around. The way the marks curved so smoothly, and never made awkward or jerky patterns, also suggested wheels rather than runners.

The width of the ruts matched the Flag Fen wheel precisely, but what interested us more than anything else was the distance between them, which was always precisely the same: just 1.10 metres. That’s hardly the width of a farm cart. Besides, the ruts were definitely made by a two-and not a four-wheeled vehicle. To my mind that clinched it: this very early wheeled vehicle was built for people. I’m sure there must have been larger goods vehicles at the time, but the fact remains that the Welland Bank ruts and the wheel and axle at Flag Fen were from a very much smaller carriage.

This is very important, because it’s not as if people couldn’t get around before. After all, we know there were plenty of boats and waterways, and besides, riding was becoming increasingly commonplace at about this time. No, I think that here we have yet more evidence for our human obsession with display and prestige. The man or woman with a wheeled vehicle was greatly superior to anyone without one. I would imagine the vehicle itself would have been made to impress, with fancy fittings and suchlike. In modern terms the light carriage was a status symbol, having more in common with a Rolls-Royce than a Mini.

The wheel ruts at Welland Bank seem to have been made off-road, probably in a wet field. I’ve no idea why somebody should take a narrow-wheeled vehicle out into a muddy field on a wet day, but people have always done strange, inexplicable things. Even in the Bronze Age wheels performed best on harder surfaces; which brings us to the much-neglected topic of prehistoric roads.

In English schools the National Curriculum starts the historical record with the coming of the Romans. As a prehistorian, this myopic decision makes me angry, and I shall continue to lobby to have it changed. The Romans were in England for less than four centuries, and although they undoubtedly left a big mark on the place and the society of its people, they were, at best, an episode. They did not form our culture; they merely influenced it. They gave us a road system, it is true, but I am convinced that there must have been an effective network of roads for at least two millennia before the Romans arrived in AD 43. What is my evidence?

FIG 22 Later Bronze Age wheel-ruts at Welland Bank Quarry, south Lincolnshire

The modern, Roman-based, system of roads uses London as a hub from which most major trunk routes radiate. We have become so used to this that we take it for granted; it even affected the way the Victorians laid out their railway system, and I believe it has had profound adverse effects, such as the general attitude of central government to the regions. The ultimate blame lies with the military-minded and control-obsessed Roman conquerors of almost two thousand years ago. Surely a more sensible way to get around the country would be based on a network of roads that tied individual communities together without any thought for the capital.

A net-like road system, without any major trunk routes, will inevitably leave a very slight archaeological trace, except in places where civil engineering is required to get across obstacles. Local roads will follow traditional routes, which in turn will tend to keep to freely-draining terrain, whilst avoiding cliffs, bogs and other natural hazards. But roads also exist to avoid human hazards. Today we think of a road as something which links point A with point B. But that is a linear way of thinking, which goes with our linear approach to other things, such as time.

Imagine a road between A and B, two settlements in a flat, featureless plain. Common sense would suggest it should follow a straight line. But it doesn’t. Instead it takes a broad, sweeping curve which respects and marks the traditional boundary between tribes C and D, who occupy the land between our two settlements. Thus the road serves more than one function: it links A and B, but it also provides C and D with a boundary which is respected by everyone. If it hadn’t followed that sweeping curve, it simply wouldn’t have worked, and A and B would remain isolated from one another.

It is often supposed that traditional boundaries were all over the place, twisting and winding their way across the landscape. In fact this was not always the case. Certainly the traditional roads would have been more sinuous than the Roman system, which was often (although not always) imposed on the landscape by unsympathetic military engineers. But it also depends on what one means by sinuous.

We have seen that Bronze Age field systems were carefully laid out to divide the landscape into family holdings of roughly equal size. From the air, the overall effect appears almost regimented, with long, straight droveways and fields set out in an orderly manner. Yet we know that these landscapes have roots extending back for millennia. So they are deeply traditional, yet at the same time their fields and droves are generally straight, or very slightly sinuous.

I believe that the droves and trackways found everywhere that field systems occur are the road system of prehistoric Britain. Over time, doubtless some became more important than others, and by the Iron Age there is increasing evidence that some traditional routes, such as the Icknield Way in Hertfordshire, were simply adopted by the Roman authorities, more or less as going concerns.

The more we discover about the organisation of Bronze Age Britain, the more apparent it is that people in widely separated parts of the country were in regular contact. There is evidence – those polished Langdale stone axes for example – of long-distance exchange, but I’m less interested in that than in the way many aspects of material culture seem to have evolved at much the same pace in different places. It’s a synchronised dance to the music of time: henges come and go; long barrows give way to round barrows; pottery styles spring up, develop and go out of fashion; roundhouses become ubiquitous; weapons grow ever more deadly; and so on. I could cite dozens of other examples, but it’s most striking how small, portable items such as pottery and metalwork change synchronously across the country throughout prehistory. It’s as if regional character developed in the form of the landscape and in the way different societies organised themselves, but despite this, the ordinary items of daily life evolved in much the same way all over the country. I’m in no doubt that people were in regular contact, often over long distances. This would have been impossible without an effective network of roads.

I’ve mentioned the Icknield Way, and there are others – Peddars Way in Norfolk and the most famous of them all, the Ridgeway which ran from Dorset up towards Avebury. In many cases these routes were also boundaries, and boundaries need regularly to be tested and reinforced. That’s why John Coles and his team have found votive offerings placed in the water alongside Neolithic trackways across the Somerset Levels: a bundle of arrows, complete pots and, most extraordinary of all, a beautiful polished stone axe made from Alpine jadeite, which is, and must always have been, a treasured item of great value. Offering it to the waters alongside the prehistoric trackway was no empty gesture.

Two summers ago I had the good fortune to visit Gill Hey’s excavation in a gravel quarry at Yarnton, in the Thames valley outside Oxford – the site that produced the notched log ladder. Gravel quarries are the same everywhere: thundering trucks, clouds of dust and weather-beaten, gravel-coloured archaeologists down on their hands and knees. This particular part of the quarry was deep within the Thames floodplain and the land was traversed by numerous relict stream channels that together comprised the braided courses of the river Thames.

We have grown used to living with tamed rivers, and the Thames is a very tamed river. The process has taken place gradually, from medieval times. It was paid for by the Church, landowners or local communities, and the engineering works mainly involved embanking and dredging. The end result was what we have today: tidy rivers that obediently flow along their allocated courses. For most of the time, that is. Like tamed tigers, they can still sometimes turn nasty.

In prehistoric times the rivers were lords of all the valleys they flowed through. If the valley was wide – as many Ice Age, glacier-widened valleys are in southern Britain – the river would spread to fit. Instead of just one course, its component streams would meander their way through the countryside; until the rains came, and then the streams would unite to form one massive sheet of water. But for most of the year the lowland river was like a partially unravelled rope – a series of roughly parallel braided streams, all flowing in broadly the same direction. This, then, was the situation Gill was confronted with at Yarnton.

We walked across several small relict streams which were now dry. You could spot them easily. The gravel was churned up and stained a dark brown colour; there were also patches of peaty mud and thick accumulations of alluvium. Gill tells me that some of the relict stream channels still flood in very wet seasons, and for a few days you can glimpse traces of the ancient river-system in the modern fields of corn. We arrived at a large relict stream-course about thirty metres wide, where Maisie was going to take some wood samples. Gill’s team had found a beautifully-constructed stone-built ford or causeway. It ran directly across the stream-bed and was five metres wide, roughly the width of a modern country road. Its size and scale and the evident engineering skill of its constructors at first led Gill to suppose that it was medieval or Roman. Such carefully-built fords from those periods are not uncommon in the area.

When Gill’s team started to raise the stonework to examine what lay below, they discovered that the rocks rested on lattice-like timber foundations which had been shaped by narrow-bladed axes that resembled Bronze Age tools. Then, a few weeks after our visit, they found Middle Bronze Age metal objects lying at the same level as the foundation timbers beneath the stones, including a very distinctive spearhead known as a socket-looped type. Spearheads of this sort don’t occur after the Middle Bronze Age. Presumably it and the other objects were sacrificed during the causeway’s construction, around 1200 or 1300 BC. The implications of this discovery are considerable.

The Yarnton causeway might suggest that road traffic was sufficiently heavy to require such elaborate engineering works. This in turn might imply that traffic had to be two-way – a single track with passing places would not have been adequate. But we must be careful: the spearhead, and also what we know about the way Bronze Age people treated boundaries and crossing places, should make us suspicious. It would be a mistake to think too functionally. My feeling is that the Yarnton ford was over-elaborated for all sorts of symbolic reasons. I don’t believe there were sufficient people and vehicles around at the time to necessitate two-way traffic. It’s a nice thought, and in many respects I hope I’m proved wrong, but given our knowledge of the Middle Bronze Age, I believe that in this instance, as in so many others, we’re seeing ideology and the world of the ancestors extending into daily life.

I’ve often been asked what the population of Bronze Age Britain was. It’s a good question, if impossible to answer now, but I think we may be in a position to make an informed estimate in twenty to fifty years. At present we lack any information from huge areas of the country, but that is changing. Today there is a proliferation of random transects through previously unexplored landscapes, brought about by archaeological research along the routes of new roads, pipelines and the like. These are throwing up unexpected evidence for settlement and land-use in areas that were previously thought to have been uninhabited in prehistory.

This new information will certainly transform the picture, but it will take time. All I can offer now is a rough-and-ready guess at the prehistoric population: say 250,000 (the population of modern Leicester) at the beginning of the Early Bronze Age, shortly before 2000 BC, and 500,000 at the end, just over a millennium later. Although these are guesses, I would be surprised and disappointed if, in fifty years’ time, archaeological demographers came up with reliable figures that were double or half that size. But then again, guesses are just that. They shouldn’t be relied on too heavily.

We can be rather better-informed at the local level. My own and others’ work around Peterborough and in nearby parts of the Fens indicates that quite large areas of the low-lying gravel plain around the Fen basin were still covered with trees at the onset of the Bronze Age. So far as I know, the hilly hinterland was not permanently settled, and the clay landscapes between Peterborough and Huntingdon to the south were almost certainly still primeval forest. Maybe we’re looking at a population in this area at that time of a few thousand. By the end of the Bronze Age large areas were cleared of trees, and there were organised field systems and substantial settlements. To my mind, this suggests a regional population of at least ten thousand, and quite possibly more. By national standards this was quite a heavily populated part of the country, so these figures cannot be extrapolated to Britain as a whole.

Professor Barry Cunliffe has suggested that the gravel floor of the Nene valley, which runs almost the entire length of Northamptonshire and drains into the Fen basin at Peterborough, was settled and farmed at the start of the Iron Age. By the third and fourth centuries BC this was not enough land to support the growing population, and more had to be cleared along the higher flanks of the valley. I can’t see this type of pressure being generated by populations of hundreds or a few thousand. We must surely be talking in terms of tens of thousands.

Another commonly asked question is, what did Bronze Age people look like? The short answer is that you can see them walking around in any north European country. They were appreciably smaller than the modern population of Britain, but this was simply a question of nutrition. Today we take it for granted that we can eat well throughout the winter, but in prehistoric times winter protein was hard to come by – and a regular supply of protein is vital for growth.

Personal appearance is about more than skin, eye or hair colour. These are just the basic ingredients, and in many respects they are not very important. We know that personal adornment was important from the very outset of the Bronze Age. Elaborate, multi-stranded necklaces, with single beads and larger spacer beads incorporating two or more threads, were made from black shale, amber or shiny black jet. Highly polished toggle-like conical buttons were made from jet and shale. These buttons were large and fancy, and I know of no evidence for buttonholes as such, so they may have simply been sewn onto fabric, rather like large sequins. Alternatively, as they mainly occur early in the Bronze Age, perhaps before the widespread adoption of loom weaving, they could have been used to secure hide or leather garments, or belts. The usual way of securing fabric was with a tie or sash band, and there were also bone, antler and metal stick-pins, rather similar to the long hatpins used by Victorian and Edwardian ladies.

The Bronze Age is famous for its goldwork, which in Britain mainly came from natural sources in Ireland and Wales. In the Early Bronze Age it was usually worked down or beaten thin, and the best-known adornments made of this thin sheet-gold are known as lunulae. As their name suggests, they were shaped like the crescent moon, and being flat they were probably worn low on the neck. Often they were decorated with slightly stiff, complex geometric designs which lack the fluidity and movement of Iron Age Celtic art almost two millennia later. Subsequently in the Bronze Age we find the first appearance of twisted, bar-like true neck ornaments, known as torcs. And there were all shapes and sizes of gold and bronze bracelets, armlets, earrings and sundry other bangles. One extraordinary example of Bronze Age beaten goldwork was found at Mold in north Wales. It is no more and no less than a short cape, highly decorated and fully large enough to cover a man’s shoulders.

Many of these finds come from burials within barrows, and it has been suggested that the day-to-day appearance of ordinary Bronze Age folk was very much more plain and simple. I’m not convinced. If elaborate personal adornment was a feature of people’s passing from this world to the next, I can’t see why their daily, routine appearance needs necessarily to have been different. I accept that one wouldn’t wear the Mold gold cape when fixing a hole in the roof, but even so, it seems to me that adornment was part of Bronze Age culture. It permeated it through and through, like music in some cultures today.

It’s a very great shame that fabric is so fragile. Clothes are, after all, the main component of our appearance, and in prehistory, just as today, they would have said much about individuals’ social status. There are also far subtler messages concealed in clothes, accessories and the way they are worn. In the Bronze Age, just as today, these would only have been understood by one’s immediate contemporaries. Sadly all of this is lost beyond recall.

Knotted or netted fabrics may well have been in use in Britain before the Bronze Age, and there is certainly evidence for the production of quite fine fibres from flax (a length of twisted flax twine was found at Etton, dating from around 3800 BC). We know that Neolithic sheep, of which the Soay breed is a survival into modern times, produce fine wool, but there isn’t hard archaeological evidence for spinning in the Neolithic. This does not mean it didn’t happen, of course. Simple spindles can be made entirely from wood, and they work well – modern craft spindles are almost always made of wood. Perfectly good fabrics can also be made by other techniques – for example felting, which involves a combination of soaking and beating wool.

Quite suddenly, towards the latter part of the Early Bronze Age, we are confronted by a wealth of evidence for the production of fabrics. Perforated disks in stone or fired clay were used as spindle whorls for drop-spinning. This is a simple technique, where a spinning-top-like spindle is tied to a length of fleece, spun between the fingers and dropped. As its weight pulls it slowly downwards it spins, and the wool is carefully teased out with both hands; this transfers the spin into the fibres. The spinning is the hardest part, but I managed to spin a passable thread after about an hour’s practice. The individually spun threads have no real strength of themselves, but by spinning two together, in the opposite direction to the way they were originally spun – a technique known as plying – they are made more than twice as strong.

Then there are the first of those axially-perforated cylindrical clay loomweights which were such an important feature of our early excavations at Fengate. These suggest the production of cloth in some quantity; they also produced cloth of much higher quality than had been possible before.

But what did the clothes look like? Weaving allows you to create patterns of texture and colour. If Bronze Age sheep did indeed resemble Soays, then they had brown fleeces. I have kept Soays for some time, and there are two quite distinct colour strains, a rich, dark chestnut brown and a paler, honey colour. There are also patches of paler wool around the rump and sometimes on the belly. It is possible too that sheep began deliberately to be bred for different-coloured fleeces at some time during the Bronze Age. Other primitive breeds, such as Shetland sheep, which may well hark back to the Iron Age breeds of northern Europe, come in a huge variety of colours: white, cream, honey, mid-brown, dark brown and near-black. By judicious selection of fleeces and parts of fleeces it would have been possible to weave colour-fast patterned cloth, without recourse to less stable dyes such as red ochre or plant extracts, for example rose madder, elderberries, blackberries, alder bark (brown/black) or alder leaves (yellow).

What did these patterns signify? Again, we can only guess, but there is some very indirect evidence to suggest that the patterning on Neolithic and Bronze Age pottery was not mere idle whimsy – abstract art, if you like. Instead it now seems probable that the decoration on pottery had something to do with the families of the people who made and used it. It wasn’t just decoration; it was more important than that. In this respect it was somewhat akin to the pattern of Scottish clan tartans. To the initiated it would have told a complex story involving family history, myth and legend. Recent examples of knitted fishermen’s sweaters in Britain are not only traditional to specific regions, but also to separate families and indeed to individuals. I wonder whether Bronze Age fabrics served a similar purpose. The patterns, the quality of the wool and the weave would have proclaimed the wearer’s social status and family background.

Most examples of Bronze Age fabric in Britain survive as slight impressions in the rust-like corrosion products of bronze, where it has been in contact with textile fibres, usually underground, after burial. I remember the first time I saw one of these imprints. It was of a woven linen fabric in the corrosion products on a bronze axe from a barrow close to the Ridgeway in Dorset, and was far finer than the picture I had had in my mind’s eye, which was of something resembling sackcloth. The textile could easily have been tailored into a pair of trousers that would not have invited unwelcome stares in Savile Row.

Complete garments, even large pieces, are unknown in Britain. So it is most fortunate that a series of remarkable discoveries have been made in Danish barrows.* As with so much Bronze Age material, these finds were in graves, so we cannot be certain that the clothes were indeed those worn during daily life. That said, they are sufficiently varied to suggest that they probably were. Woollen fabrics will be best preserved in either extremely dry or waterlogged conditions; the Danish barrows in question contained stout oak coffins, hollowed from tree trunks, which were sunk into, or enclosed within, sticky, damp clay. The combination of airless, stagnant, acid wetness and tannin from the oak is ideal for preservation, and the woollen fabrics inside the coffins were in excellent condition. In broad terms they date to the latter part of the Middle Bronze (1400–1200 BC).

The earliest fabric from within a wet oak coffin under a Danish barrow was found in 1827 by tomb robbers who chopped their way into the coffin and smashed most of the fragile contents in their search for valuable metal objects. The local priest learned about the find and managed to recover a cap and a cloak made of woven woollen fabric. This find stimulated more orderly research, which was conducted by some of the earliest pioneering scientific archaeologists in Europe, under the supervision of no less a person than the King of Denmark himself, Frederick VII. One of these barrows investigated, at Borum Eshøj, was very large, and revealed three oak coffins in which lay the remains of an elderly man and woman and a younger man. This may have been a family tomb.

The elderly woman’s coffin was revealed by workmen who didn’t realise its significance at first, so the precise arrangement of things inside it wasn’t recorded. But they included an openwork hairnet which tied below the chin. It was finely made in a knotless netting technique known as ‘sprang’. We found a charred, thumbnail-sized piece of sprang fabric in the charcoal-filled Early Bronze Age pit just outside the Etton causewayed enclosure, so it was probably a technique in widespread use at the time. It doesn’t require much equipment, and I can imagine women making sprang hairnets in the evening while sitting around the fire, or when keeping an eye on young children. It would have been the Bronze Age equivalent of knitting.

The woman also wore a short, sweater-like tunic with three-quarter-length sleeves and a wide crew-neck. Her full skirt was ankle-length, secured at the waist by a woven belt which passed around the body twice. The ends of the belt were finished as tassels. Among the items placed in the grave with her was a torc neck-ornament, a bone comb, two bracelets, three decorated bronze discs (which were probably worn at the midriff), a dagger and a finely decorated safety-pin-style brooch. To judge by this array of fine things, she was obviously a person of some standing.

Her husband’s coffin was excavated by archaeologists from Denmark’s Museum of Northern Antiquities. Its bark had been removed on the spot, and debris from this process lay around it. This might suggest that the ritual removal of bark was part of a purificatory process that took place during the funeral. When the massive lid was opened it revealed a man lying on his back, with his arms at his sides. He wore a thick woollen cap, his face was clean-shaven and his fingernails had been looked after with some care. He was aged fifty to sixty and was 5 feet 7½ inches tall. He suffered from rheumatism, and would have walked stiffly or with a limp. He wore only a woven knee-length, skirt-like loincloth, but he lay on a cow hide and a woven cape had been placed over him. At his feet were two woollen foot-wraps.

The body of the young man, who may or may not have been their son, was superbly preserved within its coffin, which had also had its bark removed. He wore a long, shirt-like tunic, held at the waist by a leather belt secured with a wooden toggle. At his right shoulder were the remains of a broad baldric (a sword-belt that passed from one shoulder to the opposite hip). Like his father’s, his body had been draped in a voluminous cloak, and at his feet were traces of leather sandals.

But the discovery that brought the past to life most vividly was made in an oak coffin inside a barrow at Egtved Farm in southern Jutland (the mainland part of Denmark) in 1921. Like the coffins at Borum Eshøj, this one too had had the bark removed. The body was that of a young woman, and, as many archaeological commentators have noted, she was wearing ‘summer clothes’. Certainly the way she dressed would not have been appropriate to the rigours of a Danish winter, but in the sixties I can recall students wearing mini-skirts on winter evenings. Besides, there’s always such a thing as a good, long, thick cloak if it’s needed. I suspect her clothing isn’t in itself conclusive evidence that she died during the summer, but simply that she was wearing a young person’s clothes, and wouldn’t have been seen dead wearing the older women’s long skirts. Sadly, as it happened, she had her wish fulfilled.

Her coffin too was remarkably well preserved. It consisted of an oak tree trunk which had been split in half and the centre hollowed out. No attempt had been made to smoothe off the join between the split halves, which was left unfinished and consequently fitted together snugly, as if the people who made the coffin wanted the join between the halves to be seamless. Invisible. As if she had been enclosed within a de-barked tree trunk.

She lay beneath a cow hide, which in turn covered a large piece of woollen cloth that enveloped her body from head to toe. She had been buried during the summer, as the coffin contained the flowers of the medicinal herb yarrow, which grew round about, and was barely twenty years old at death. She wore a thigh-length skirt made simply of braided woollen cords joined at the waistband and hem. The cords themselves were loose and had not been interwoven. The effect, when she moved, would have been sensational. Archaeologists at the time of her discovery were lost for words to describe it. Was it, they wondered, an underskirt? Moreover, she wore no pants beneath it. I will pass on rapidly. Her midriff was bare except for a woven belt which held in place a decorated bronze disc in front of the navel. On her top she wore a short tunic with three-quarter-length sleeves and a high crew-type neck, similar to the one worn by the older woman from Borum Eshøj. As an outfit it was young, attractive and bursting with life. Certainly it was sexy and provocative, too. But then, that’s what a normal youth in any culture has always been about. Without that joie de vivre and drive, the species would soon die out. I still find that young woman’s grave almost unbearably poignant.

There were other finds of clothed bodies, but one in particular is relevant to our story. The mound of Muldbjerg is in hilly country in north-west Jutland, and was dug by a team of archaeologists from the Museum of Northern Antiquities in 1883. In this instance I don’t want to concentrate on what was found inside the coffin so much as on the coffin itself and the way it had been positioned in the ground. Having said that, the dead man, described by P.V. Glob as the ‘Muldbjerg Chieftain’, was out of the ordinary. He was clean-shaven, his clothes were well-made, he wore leather shoes and was accompanied by a fine sword in its scabbard.

His oak coffin had had the bark carefully removed and had then been placed on a bed of large rounded cobbles. But in this instance the coffin was not alone. It lay beneath half the trunk of a much larger oak tree, which had been hollowed out and fitted over it, like a close-fitting protective vault. Although it could easily have been removed, the bark still survived intact in many places on this outer container. It was clearly an arrangement that was rich in symbolism, and involved much painstaking labour. It must have taken many men several days to complete work on the coffin and its wooden ‘vault’. In the end, the effect they achieved was of a trunk within a tree. It was a theme that a different team of archaeologists would encounter on the other side of the North Sea, 116 years later.

* It may be worth recording here that the average floor area of Iron Age roundhouses at Fengate compares favourably with terrace accommodation provided by the Great Northern Railway Company for its Peterborough employees in 1850.

* These Danish finds are so remarkable that they deserve a book to themselves, not just a few lines. Happily that book has been written, by the Danish archaeologist P.V. Glob: The Mound People: Danish Bronze Age Man Preserved (London, 1974). I recommend it highly.