CHAPTER 2

January 29, 1774, was undoubtedly a frigid, wintry day in London. But if Benjamin Franklin trembled when he stepped outside his house on Craven Street, it was probably due not to the cold, but to the trepidation he felt as he walked the short distance to his important legal summons in front of the King’s Privy Council. Portly and balding, Dr. Franklin—as he was fondly called in reference to the honorary degree given him in 1759 by Scotland’s University of St. Andrews—had spent the better part of the last fifteen years in London, and had just recently turned sixty-eight.

Now he made his way along the possibly snow-covered cobblestones, perhaps accompanied by a small entourage that included his legal counsel. Franklin was to serve this day as agent for Massachusetts, though he also officially represented the interests of three other provinces.1 As such, he appreciated that his job would prove more difficult than usual, given the news of the Tea Party just then arriving in London.2

Soon he came upon the octagonal two-story Cockpit, one of the only buildings that remained after a fire a century earlier had destroyed the adjacent great Palace of Whitehall. The Cockpit drew its name from the barbaric entertainment of cockfighting it once featured, long forbidden by the time of Franklin’s visit. Instead, the Cockpit now featured the more civilized sport of politics. But the spectacle that was to transpire this day would seem remarkably similar to an actual cockfight. Franklin was walking into a trap, and perhaps he knew it.3

Inside, politicians, nobility, and other spectators crowded the entryway into the small chamber. Of note, in attendance were the Prime Minister, Lord North; the Archbishop of Canterbury; the Whiggish and influential Lord Shelburne (a future Prime Minister); and the most outspoken friend of America to be found in the House of Commons: the Whig Edmund Burke. Burke noted there were thirty-five Privy Council members in attendance—a number he claimed was without precedent. At the head of the Council and behind the podium sat Lord President Granville Leveson-Gower. The spectators who packed the remainder of the floor and the balcony above included Franklin’s good friend Joseph Priestley and Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage, Commander in Chief of the British Army in North America, temporarily on leave in England.4 Excitement and whispers filled the room as the crowd watched Franklin and his entourage enter center stage.

Lord President Gower called the room to attention, and the hearing began with the reading of a letter and its two enclosures from Franklin to William Legge, second Earl of Dartmouth, Secretary of State for the Colonies. The most important enclosure was a petition from the Massachusetts General Assembly to the King requesting the removal of the colony’s Royal Governor, Thomas Hutchinson. (The other enclosure gave the assembly’s Resolves on the matter.)5 This petition made the serious allegation that Hutchison had undermined all attempts at peaceful resolution between the colony and the mother country; that this one mischievous man charged with managing Massachusetts on behalf of the benevolent King was in fact the central cause of the present conflict.

As proof of Hutchinson’s treachery, the Massachusetts petition provided thirteen private letters, mostly written by Hutchinson and Lt. Gov. Andrew Oliver to an unnamed recipient in England. The letters had since been intercepted and published in America.6 These were now read before the packed crowd at the Cockpit.7

The letters themselves were in fact quite mundane, and several even had words expressing Governor Hutchinson’s sorrow over the troubles in Massachusetts. But because Hutchinson was the Crown-appointed leader who had dutifully supported parliamentary efforts to tax Massachusetts over the past decade, he became the easy scapegoat for Boston radicals, and they wanted to see him ousted.8

To make their case, the radicals had latched on to the very few lines of those private letters that sounded most tyrannical, the most damning of which, written in the wake of violent mobbing and riots in Boston, was: “There must be an abridgement of what are called English liberties… I wish the good of the colony when I wish to see some further restraint of liberty, rather than the connection with the parent state should be broken; for I am sure such a breach must prove the ruin of the colony.” Radicals ignored that in the same letter, Hutchinson added, “I never think of the measures necessary for the peace and good order of the colonies without pain.”9

Rather, the two most incendiary comments were found in two letters not authored by Hutchinson at all, though they were included among the rest and read aloud in the Cockpit hearing. One was by Lt. Gov. Andrew Oliver, who stated, “if [crown] officers are not in some measure independent of the people (for it is difficult to serve two masters), they will sometimes have a hard struggle between duty to the crown and a regard to self”.10 This was a hotly contested issue in America, because such a law would strip the people of fiduciary power over their governing officials, allowing their leaders to become unbridled despots.

But the most offensive letter was by neither Oliver nor Hutchinson, but by Custom Commissioner Charles Paxton, who penned, “Unless we have immediately two or three regiments, ’tis the opinion of all the friends to government, that Boston will be in open rebellion.” In other words, Paxton was calling for Boston to be placed under military occupation.11

After the letters were read, the hearing turned to Franklin himself, for the famed American was not merely in attendance as a representative, but also as a defendant, having played a part in the publication of the Hutchinson letters. Defending him were prominent British lawyer John Dunning and a young American lawyer in London, Arthur Lee, who together began describing the events leading up to this moment.12

As they explained, Franklin had obtained the private letters months earlier from a secret informant sympathetic to the colonies. How they came into his hands remains a mystery,13 but Franklin forwarded them to the Massachusetts General Assembly for its members’ consideration. The one stipulation, imposed by Franklin’s secret informant: they were not to be copied or printed.14 The General Assembly at first published only an announcement of the general implications of the letters. But then, after some debate, they had all the letters printed in the Boston Gazette. When the public read them, those few comments in the letters led to outrage.15

Franklin probably expected the letters to be published from the start, and perhaps hoped they would be, but he could never encourage it, per his informant’s instructions. But once his role became public, Franklin later justified himself to the newspapers: “They were not of the nature of private letters between friends. They were written by public officers to persons in public stations, on public affairs, and intended to procure public measures; they were therefore handed to other public persons, who might be influenced by them to produce those measures. Their tendency was to incense the mother country against her colonies…which they effected.”16

All of this was discussed before the Privy Council and the many spectators there at the Cockpit, while Franklin himself remained silent as his counsel “acquitted themselves very handsomely”.17

Finally, it was the opposition’s turn. Hutchinson and Oliver were still attending their duties in Massachusetts, but their agent Israel Mauduit stood nearby with his legal counsel, the haughty forty-year-old Scotsman Alexander Wedderburn, the solicitor general, infamous for his venomous sharp tongue. Wedderburn had been impatiently looking forward to his moment in center stage, and now this political predator was free to feast on his prey.18

The anxious spectators drew to the edge of their seats. They knew the real show was about to begin.

• • •

Dressed in a suit of spotted velvet, Franklin stood in the center of the room, conspicuous not only because he was perhaps the only balding man present—for the rest wore wigs or powdered their hair white—but because he represented the rebellious American colonies.19 Some of the ladies there gazed at Franklin with great attraction, strange as that may seem, for the portly sixty-eight-year-old Yankee carried an aura that drew their fond fascination. But Wedderburn, as if to savor the moment before the kill, gave Franklin only a steely gaze before he pounced.

Benjamin Franklin Appearing before the Privy Council, 1774 — engraving by Robert Whitechurch (1814–c. 1880), c. 1859, based on a painting (c. 1859) by Christian Schussele (1824–1879). Engraving courtesy of the Library of Congress. (Original painting in the Huntington Art Collections, San Marino, California.)

The solicitor general began with a biased history of the events so far, as if to prime his audience for some tragic Shakespearean play, the fallen hero to be Governor Hutchinson.20

Whatever Wedderburn’s version of this history, the roots of the turmoil had begun with two events. First was the accession in 1760 of George III as King of Great Britain and Ireland, and the King’s move to strengthen the monarchy into one that led Parliament, instead of merely serving as its figurehead.21 The second was the Seven Years’ War, fought in Europe and North America, with the American campaign known as the French and Indian War. It pitted the British against the French for the right to the undeveloped expanse west of the coastal British colonies. Action on the American front ended by 1760, the war itself in 1763, and the French ceded New France (Canada and claims east of the Mississippi) to Britain. But Britain also gained a massive debt—£122,603,336 in January 1763, plus an annual interest rate of about 3.6 percent, compounded further by the greater costs of managing an enlarged empire.22

So, Britain looked to the prosperous and untapped colonies as a lucrative source of taxation to help refill its depleted coffers. After all, had Britain not expended most of its treasure to protect the American colonies from French and Indian threats along its western borders? The first attempt was the Sugar Act of 1764, but it had unintended consequences that drove the British economy into a postwar depression when it effectively killed the lumber, iron, and rum trades.23

Next, continued Wedderburn, was the Stamp Act of 1765, which required an inexpensive stamp to be affixed to a wide array of legal and trade documents, newspapers, newspaper advertisements, and even playing cards and dice, effectively ensuring that all classes of society would somehow be burdened by the new tax.24 Americans were outraged—politicians rallied to “no taxation without representation”, and extralegal mobs calling themselves the Sons of Liberty led days of riots, the greatest of which were in Boston, led by Samuel Adams.25

When Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in 1766, Americans were too busy celebrating to pay attention to the Declaratory Act of the same year, which affirmed that Parliament had “full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America, subjects of the crown of Great Britain, in all cases whatsoever.”26

Parliament then passed the Revenue Act of 1767, which applied various import duties (a more discreet form of taxation), but also explicitly earmarked those revenues to pay for crown officers in the colonies.27 This latter stipulation re-enraged the colonists, who “thought they read their own annihilation”, believing it would give civil officials unbridled control and turn the populace into abject slaves.28 With such wholesale governmental restructuring, the Revenue Act singlehandedly changed the face of the political debate. No longer was the argument over taxation, though it would remain so on the surface. Now the debate became one of constitutionality, liberty, and self-determination. Even the oft-repeated phrase “no taxation without representation” became not about taxation, but about the authority of Parliament. That the British continued to simplify the debate to that of taxation is what led in part to the great divide between the mother country and her colonies.29

As Wedderburn reminded his audience, to fight the Revenue Act, the American colonies began an unprecedented nonimportation agreement, first only on the dutied goods listed in the Revenue Act, then on all British goods and all tea from any source whatsoever.30 Boston was at the center of it all, and Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage, the British Army commander in chief then serving in New York, sent two regiments of troops to Boston to help control the mobs.31 This led to still greater tension that culminated on March 5, 1770.

When an angry Boston mob violently harassed a handful of British troops, shots were fired, and five townsmen died, with another six wounded. Paul Revere famously engraved a gross misrepresentation of the affair, and the Sons of Liberty absurdly called it the “Boston Massacre.” In response, Massachusetts’s Governor Hutchinson reluctantly withdrew all British troops to Castle William in the harbor.32 On April 12, 1770, the Revenue Act was mostly repealed, except for a lingering duty on tea.33 The nonimportation agreement was then abandoned, and a tentative peace returned to the colonies.

Then there was the Tea Act of 1773.

Throughout Alexander Wedderburn’s biased version of the history, he painted Governor Hutchinson as a benevolent man of service, a struggling keeper of the peace, not the villain.

The theatrical solicitor general next turned his oration to the Hutchinson Letters Affair and the resulting allegations brought against Hutchinson and Oliver. “My Lords, they mean nothing more by this Address, than to fix a stigma on the Governor by the accusation… The mob, they know, need only hear their Governors accused, and they will be sure to condemn.” “There is no cause to try—there is no charge—there are no accusers—there are no proofs.”

Indeed, Wedderburn was right. Boston radicals had manipulated public opinion to ensure Hutchinson’s condemnation. (True, Hutchinson had proved himself a poor leader in failing to resolve the conflict leading to the Tea Party, but news of this was just arriving in England.)34 Wedderburn then persuaded the lords that it was not Hutchinson, nor his predecessor, that had brought troops into Boston; it was the insolence of the colonists themselves.35

Content he had sufficiently exonerated his clients, Wedderburn then used his cunning tongue and carefully contrived argument to shift his entire examination from Hutchinson and Oliver onto Benjamin Franklin. “Dr. Franklin…stands in the light of the first mover and prime conductor of this whole contrivance”. This was surely one of those times that the audience chuckled, as Wedderburn probably punctuated “prime conductor” in reference to Franklin’s experimentation with electricity. He continued, “[H]e now appears before your Lordships to give the finishing stroke to the work of his own hands. How these letters came into the possession of any one but the right owners, is still a mystery for Dr. Franklin to explain.”36

By now, Wedderburn was playing more to the room than the Privy Council. “I shall now return the charge, and shew to your Lordships, who it is that is the true incendiary, and who is the great abetter of that faction at Boston”.37 The solicitor general danced about the center of the room, stoking the fervor of the crowd and bashing the “wily American” Franklin for nearly an hour, and soon his oration shifted from haughty to scathing. “The letters could not have come to Dr. Franklin by fair means… I hope, my lords, you will mark [and brand] the man, for the honour of this country, of Europe, and of mankind… Men will watch him with a jealous eye; they will hide their papers from him, and lock up their escrutoires [writing desks].” Wedderburn must have then paused to enjoy the cleverness of his next statement. “He will henceforth esteem it a libel to be called a man of letters [an intellectual]; homo trium literarum!” This was fancy Latin wordplay, but it translated simply: Wedderburn had just called Franklin a thief!38

Throughout the ordeal, Franklin “stood conspicuously erect”, keeping his “countenance as immovable as if his features had been made of wood.”39

Finally, Wedderburn turned his attention from his excited crowd to the Privy Lords and delivered his final words with utter condescension: “But if a Governor at Boston should presume to whisper to a friend, that he thinks it somewhat more than a moderate exertion of English liberty, to destroy the ships of England, to attack her officers, to plunder their goods, to pull down their houses, or even to burn the King’s ships of war, [it is] he [that] ought to be removed[?]”40

Wild applause erupted. Wedderburn had practically hypnotized the Privy Council with his snake tongue. It is no wonder then that days later, Hutchinson and Oliver were absolved of all charges against them, the Massachusetts petition for their removal rejected. Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage, who had watched the entire affair, rejoiced at Hutchinson’s victory, thinking the practice of prying into others’ mail was a “damn’d villainous” one. But the fair-minded general also lamented Franklin’s humiliation.41

Though the great philosopher remained stoic throughout, Franklin was deeply wounded by this betrayal of his government. He had previously been working in earnest to temper both sides of the ideological dispute, urging compromise and understanding between the mother country and her colonies. He had even served His Majesty directly as postmaster general for America, though that office would be stripped from him in the coming days.42 The dejected Franklin would soon make plans to at last return home to Pennsylvania, though he would not in fact make the trip until 1775.

The Hutchinson Letters Affair was symbolic, for it not only represented Franklin’s rift from his fealty to the English government, a division that would send him into the company of American radicals, but it also paralleled the rift British America would soon undergo from her parent state. The Hutchinson Letters Affair was thus the beginning of the Revolution in miniature.

• • •

On February 4, 1774, shortly after having watched the Hutchinson Affair at the Privy Council, Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage received the honor of an audience with His Majesty King George III. These two men, whose decisions and measures would shape the fate of a country across the ocean, met in the court at St. James Palace in London.

At just thirty-five, George III was still a young king. Lord Waldegrave, a court official during George’s earlier years, wrote of him before he ascended the throne: “He…will seldom do wrong, except when he mistakes wrong for right; but as often as this shall happen, it will be difficult to undeceive him, because he is uncommonly indolent and has strong prejudices”.43 Indeed, the American problem would be one instance where the King would mistake wrong for right.

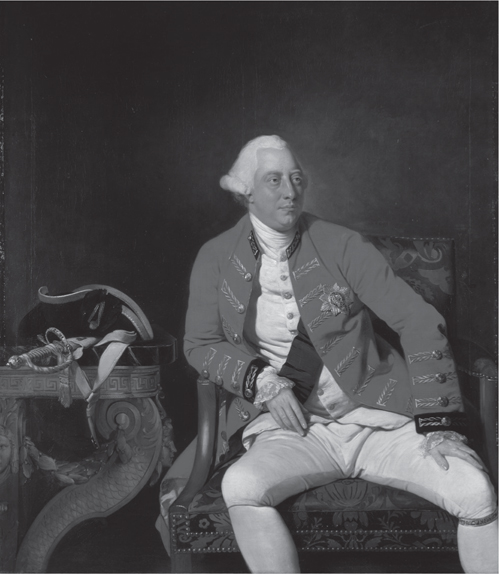

Portrait of King George III (1771) by Johann Zoffany (1733–1810). Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2015/Bridgeman Images.

On this day, His Majesty was anxious to have Gage’s valued opinion on the present crisis, because the fifty-four-year-old lieutenant general was very familiar with life and politics in the thirteen colonies. Gage had served admirably under British Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock in the last war against the French and the Indians and had fought in 1755 at the devastating British defeat known as the Battle of Monongahela near modern Pittsburgh. There, Gage witnessed firsthand the heroic efforts of Braddock’s aide-de-camp to organize the retreat and bear the mortally wounded Braddock from the field. That aide-de-camp was the little-known Virginian named George Washington.

Later in the war, Gage had married a well-to-do American woman from New Jersey named Margaret Kemble. And since 1764, following the end of the war, Gage had served as commander in chief in North America, spending most of his time in New York, though now on temporary leave in England.44

Honored to give his advice to his King, Gage expressed “his readiness[,] though so lately come from America[,] to return at a day’s notice if the conduct of the Colonies should induce the directing coercive measures”. Gage thought the Americans would be “Lyons, whilst we are lambs”, but if government took “the resolute part they will undoubtedly prove very meek”, and he thought four regiments earmarked for New York would be sufficient to keep order in Boston while its inhabitants were punished for their conduct.45 Such a haughty boast! But this was how many Britons saw the Americans, as spoiled children in need of proper discipline.

Portrait of Frederick, Lord North, later 2nd Earl of Guildford, (date unknown), by Allan Ramsay (1713–84). Private Collection/Photo © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images.

These words were unusually aggressive for the otherwise mild-mannered Gage, but while he had faith in his forces in America, he never claimed they could maintain order in Boston under all circumstances. King George III, however, was much more aggressive, writing later to his prime minister, Lord North, “once vigorous measures appear to be the only means left of bringing the Americans to a due Submission to the Mother Country…the Colonies will Submit”.46

It took a few weeks to gain momentum, but soon Parliament and the British Ministry were indeed demanding vigorous measures. First were the calls to bring those involved in the Destruction of the Tea to trial in Britain, which was considered for a time, but soon “the project was dropt”, for there was no hard evidence by which to implicate anyone.47 Then it was decided that if the instigators could not be identified, perhaps the whole colony should be punished. By the end of February, the Ministry was calling for coercive measures against all of Massachusetts.

The first proposed measure was to close the Port of Boston. The King had in his authority the power to issue orders to Admiral Montagu there to effect the blockade, but John Pownall, assistant to Colonial Secretary Lord Dartmouth, suggested the port be closed by law instead. This way, King George could save face, maintaining his reputation as a benevolent sovereign while Parliament became responsible for the coercive measures.48

On March 14, 1774, Lord North rose before the House of Commons and gave a speech prompting the debate of the Boston Port Bill. He declared it impossible for “commerce to be safe whilst it continued in the harbour of Boston,” and asserted that “the inhabitants of the Town of Boston deserved punishment.” Citing other precedents, North justified punishing the whole town for the sins of the few.49 Charles Van of the Commons agreed, stating he was “of opinion the town of Boston ought to be knocked about their ears and destroyed… you will never meet with that proper obedience to the laws of this country until you have destroyed the nest of locusts.”50

The proposed Port Bill would not only close the port, but also move customs to a new port of entry at Plymouth. The tyranny of the bill lay in its qualification for rescindment. “The test of the Bostonians will not be the indemnification of the East India Company alone, it will remain in the breast of the King not to restore the port until peace and obedience shall be observed in the port of Boston.” In other words, only when the Ministry was satisfied that the people of Boston were sufficiently pacified would the port be reopened.51

Some in Parliament, however, thought the Port Bill too severe. Rose Fuller thought so, warning the Commons that if Boston did not submit, there would be no choice “but to burn their town and knock the people on the head.” Fuller predicted that if troops were sent to enforce the bill, the Americans would unite and crush them, and he reminded the Commons that the colonists all had arms and knew how to use them. Despite these few friends in Parliament, the Whig Party would not let their sympathy for America justify the destruction of private property. Lord Chatham, a staunch ally to the colonies, termed the Tea Party a criminal action and showed no interest in lending his name to the opposition. The Boston Port Act unanimously passed both houses and received the King’s assent on March 31. It would go into effect on June 1, 1774.52

This was not the end of Lord North’s diabolical scheme. North thought harsh punishment would force Boston back into line, while sending an important message to other British colonies. So, immediately after the Port Bill passed the Commons, even before the House of Lords or the King had given it their approval, North revealed his grander strategy. On March 28, he proclaimed that “an executive power was wanting in that country [of Massachusetts], and that it was highly necessary to strengthen the magistracy of it”, and because power there presently rested with the mobs, he so proposed the Regulating Bill. It called for the stripping of democracy from the populace, effectively rewriting the Massachusetts Charter granted by predecessors of the Crown and giving the governor unparalleled power to appoint his own council, judges, and even jurors. The most radical provision limited town meetings to once a year, and only then to elect assembly officials and make rules for local administration. Any special meeting beyond this would require the governor’s approval.53

The debate ensued well into the next two months, and American petitions to have a say in the proceedings were ignored. The Whigs, being fundamentally against absolute rule, mounted a heated opposition. “Can this country gain strength by keeping up such a dispute as this?” argued Charles Fox before the Commons, stating that Parliament had no authority to modify a Crown-granted charter. Calling it a crime, he added, “I look upon this measure to be in effect taking away their charter…it begins with a crime and ends with a punishment; but I wish gentlemen would consider whether it is more proper to govern by military force or by management.”54

Edmund Burke protested against the bill on the grounds that Parliament refused to hear from the aggrieved Americans. “Repeal, Sir, the Act [the remaining tea duty] which gave rise to this disturbance; this will be the remedy to bring peace and quietness and restore authority; but a great black book and a great many red coats will never be able to govern it.”55 Despite the spirited opposition, the bill passed both houses with almost an 80 percent majority, becoming the Massachusetts Governing Act and receiving the King’s assent on May 20, 1774.56

Lord North was not yet done. Concurrently with the Governing Act, Parliament debated the Administration of Justice Bill, which gave more powers to the governor and allowed him to remove criminal trials to England or another colony, thereby eliminating the right to a fair trial by one’s own peers. This bill also passed with an almost 80 percent majority, receiving the King’s assent on the same date as the other, May 20.57 Finally, on June 2, Lord North’s fourth and final bill received the royal assent. This was the Quartering Act of 1774, which required Massachusetts to supply and barrack the troops sent there at their own expense, and that the troops were to be stationed in the town proper, or wherever their service was required as determined by the crown officers, thus eliminating Boston’s previous claims that the barracks in secluded Castle William met their obligations.58

The Boston Port Act stripped the people of their right to trade. It would destroy businesses, skyrocket unemployment, and starve the people. The Massachusetts Governing Act eliminated their democracy and liberty and made their governor a virtual dictator. The Justice Act eliminated their right to a fair trial. The Quartering Act ensured troops would be garrisoned in their very midst. Together these were the Coercive Acts. (Historians a century later would rename them the Intolerable Acts.)59 Americans would include among the Coercive Acts the unrelated Quebec Act, passed on the heels of the others. Though the Quebec Act would have little bearing on the immediate crisis, it would eventually alter the shape of the coming war.60

The British Ministry had one final coercion up its sleeve. In a twist of irony, Massachusetts had petitioned for Governor Hutchinson’s removal, for which Benjamin Franklin had met before the Privy Council. Though their petition was initially rejected, now they would have it. Governor Hutchinson had requested leave to visit England. Meanwhile, Lt. Gov. Andrew Oliver was ailing and, though the news had not yet reached London, had died of a stroke in early March.61 So the Ministry came up with a brilliant plan. Why not grant Hutchinson his leave and make Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage the new military governor of Massachusetts? Surely, Governor Gage could obtain, if necessary, military aid from General Gage.62

By early April, Gage had sent orders to his deputy in New York, Major General Haldimand, to provide a staff for him at Boston. Gage then arranged for his wife to return to New York, away from the turmoil in Boston. Finally, on April 16, 1774, Gage set sail for Boston aboard the 20-gun warship HMS Lively.63

England was determined to use force to gain submission from Boston. They believed the other colonies would sit idly by and watch its destruction. But the American colonies would indeed unite, and Boston would not so easily submit.