CHAPTER 9

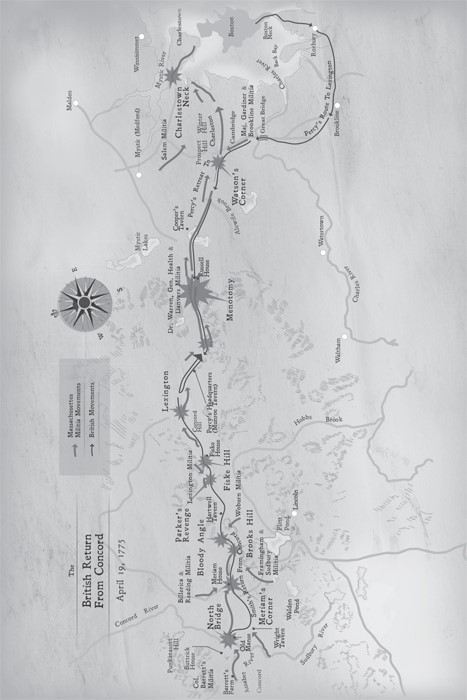

The first mile back toward Lexington was mostly uneventful. The long, red column now marched with the sun high above, the sunbeams glistening off their fixed bayonets, the men weary, hungry, and thirsty. At least two wounded British officers rode ahead in a horse-drawn chaise: Lt. Edward Gould, despite his injured foot, driving it like an ambulance, racing to ferry critically wounded Lt. Edward Hull to Boston. The nasty gunshot wound to Hull’s right breast was hemorrhaging profusely.1

As the British left Concord, the ridge now stood on their left, while most of the dirt road they traveled was lined with knee-high rock walls, gathered and stacked from the rock-studded pastureland and gentle hills on their right, which was mostly open space, though dotted here and there with sparse, young woods, broken by farms and the occasional apple orchard. The British light infantry felt greater fatigue than the grenadiers, having that morning run ahead to Lexington, then having traveled beyond Concord center to the North Bridge and Barrett’s Farm, and now serving as flanking parties off the road, some in the fields south of the column, others along the steep acclivities to the north.

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to the British, the Yankee militia and minuteman companies from Concord’s North Bridge had finally, after consultation, decided to press the war. Familiar with all the back ways, they crossed from Concord center, up the slopes that governed its eastern boundary and down the other side, following a northern path that paralleled the British march but kept the slopes between them. These slopes fell away at a point near the house of Nathan Meriam, still standing, where the Bedford Road met the Concord Road, and it was there, at Meriam’s Corner, that the Americans intended to ambush the British.2

The tail of the British column had no sooner departed Concord center than a few independent militia parties from the North Bridge began firing scattered shots at their rear. The militia mostly sniped from behind trees and out windows of innocent-looking houses, adopting the guerrilla-style warfare observed and learned so well during the last war against the French and Indians. Other scattered Yankee parties, many of whom were newly arrived to the fight from neighboring towns, also took their potshots at the British flanks.

Despite many stories to the contrary, the British did not march blindly and ignorantly as a single column under such galling fire. Rather, the light infantry deployed far off road to defend the column’s flanks by rooting out and swarming militia snipers. In fact, the light infantry was a rather new evolution in warfare, also a product of the last war with the French and Indians, and so fought with the same tactics the militia employed: moving in numerous but small, independent parties, taking cover behind trees and rocks, running from one cover to the next.3 Lieutenant Sutherland, delirious due to his hemorrhaging right breast, remembered seeing the lights kill two pursuing militiamen, though two of the British themselves were also wounded in defending the main column.4

The lights performed their job admirably, allowing the main British column to progress without much harassment or loss for more than a mile. But as the lights on the British left came to the end of the slopes, which fell away at Meriam’s Corner, they saw two large bodies of militia coming along a northerly road from Bedford, with a larger third body farther away. The latter was the main body of colonial militia that had been at North Bridge and had come around the heights of Concord too slowly to effect their intended ambush. Of the two nearer bodies, the leading was the four militia companies of Reading, distantly followed by the three of Billerica.

Capt. John Brooks, who would be promoted to major for his service this day, was at the head of these Reading men. As they made their way southward, one of his men observed, “The British marched down the hill with very slow, but steady step, without music, or a word being spoken that could be heard. Silence reigned on both sides.”5

In following the slopes’ topography back down to ground level, the light infantry necessarily found themselves pressed in close proximity to the main column, very near the road. The Concord-Lexington Road continued eastward past an intersection that defined Meriam’s Corner, then grew narrow as it approached a small, wooden bridge, just a few feet in length, that crossed an upstream stretch of the same Mill Brook that wound through Concord.

Modern road construction practically obscures this small crossing, but in that era the narrow bridge caused a bottleneck as it forced even the dispersed British flankers to draw in tight with the main column to cross it. The Reading companies saw this opportunity and rushed forward, taking cover behind Meriam’s barn and the farm’s nearby walls, a position about three to five hundred feet away from the bridge. And from there the Yankees opened fire.6

The first balls whizzed harmlessly by the British lights, totally ineffective at such range. The lights gave a few futile shots in return, defending the main British column as it struggled to speedily cross the narrow bridge. Determined to inflict casualties, the Reading militiamen reloaded as they crept closer to the bridge, taking cover behind rock hedges and trees. At the same time, the two other bodies of militia, those from Billerica, distantly trailed by those from the North Bridge, rushed south along the Bedford Road to join the fight. With the Americans closing in, both opposing adversaries began brisk fire, the most intense shooting of the day thus far. The Americans kept pressing southward between each reload until the lights found their backs against the main column. The grenadiers comprised the bulk of that main body, and now they too halted, midway in crossing the bridge, to give their own volley.7

The field between the Meriam House and Mill Brook was quickly shrouded in thick white smoke. Both sides fired briskly and incessantly. The din increased dramatically as the Billerica men joined the Reading men. Severely wounded, Lieutenant Sutherland was probably somewhere in the center of the column on his horse-drawn wagon, laid therein headfirst so that he could only see the fight once his wagon passed it. He saw the Americans “came as close to the road on our flanking partys as they possibly could”.8 To push the Americans back, Ensign Lister led his fatigued 10th Lights in a counterattack away from the main column. As he did, an American musket ball smashed into his right elbow, shattering the joint and instantly disabling his arm, his fusil musket falling from his limp limb. He grabbed his fusil with his good arm and fell back.9

Sutherland thought the colonial force thus far engaged was much larger than at North Bridge, and indeed it was. Comprising men from both Reading and Billerica, augmented by another two companies just then arriving from Chelmsford, the force swelled to near 500. When the laggards from the North Bridge at last joined the fight, the total came to somewhere near 900 men.10 With just under 790, the British were now very much outgunned.11

Suddenly, balls began to whiz across Sutherland’s wagon from the south. He turned his attention there and found a second small force, probably the lead companies of Sudbury and Framingham, whom he suspected meant to join the first and together attack the British van.12 As all of these militia companies were bound for Concord center, it was easy for them to divert from their path and find where the fight had now progressed—they needed only follow the thunderous and incessant booms of the musketry. Meriam’s Corner marked the beginning of a long and bloody running fight all the way back to Boston.

It is impossible to determine how many casualties each side suffered at the skirmish at Meriam’s Corner, just as it is at any point along what is now known as Battle Road. While the Americans kept their cover and perhaps made it through this skirmish unscathed, depending on the account, as few as two or as many as nine or more British died or lay there wounded and incapacitated, with another several wounded but marching off with the column. According to Concordian Amos Barrett, late to the fight as he had come with those from the North Bridge: “When I got thair was a grait many Lay Dead, and the Road was bloody.”13

Once the entire British column crossed the narrow bridge, they quickly pressed onward. The Americans regrouped and then crossed it themselves, giving scattered shots at the British rear as they pursued. The Yankees then fanned out as fast as they could to either flank of the British, taking to the fields and woods, trying to get ahead of the British column from where they could take multiple potshots each. All the while, new militiamen poured in from the surrounding areas, some in small parties, some as individuals. One late participant reminisced, “The battle now began, and was carried on with little or no military discipline and order, on the part of the Americans, during the remainder of that day. Each one sought his own place and opportunity”.14

According to Lister, the battle “then became a general Firing upon us from all Quarters, from behind hedges and Walls[;] we return’d the fire every opportunity”.15 Smith observed, “they began to fire on us from behind the walls, ditches, trees, &c., which, as we marched, increased to a very great degree, and continued without the intermission of five minutes altogether… I can’t think but it must have been a preconcerted scheme in them, to attack the King’s troops with the first favourable opportunity offered, otherwise, I think they could not, in so short a time…raised such a numerous body”.16 Barker confided to his diary, “the Country was an amazing strong one, full of Hills, Woods, stone Walls &c., which the Rebels did not fail to take advantage of…as we did too upon them but not with the same advantage”.17

One participant, apparently an officer of the 23rd Welch Fusiliers, complained that most of the soldiers had never been in action. As a result, in the confusion of the running fight, the troops fired back “with too much eagerness, so that at first most of it was thrown away for want of that coolness and Steadiness which distinguishes troops who have been inured to service.” The same Welch Fusilier officer added, “The contempt in which they held the Rebels, and perhaps their opinion that they would be sufficiently intimidated by a brisk fire, occasioned this improper conduct; which the Officers did not prevent as they should have done.”18

Under these conditions, the British managed to plow ahead along the Battle Road. After another mile, they approached the Noah Brooks Tavern, which lay just east of a small wooded mound known as Brooks Hill. It was there that the main forces of Sudbury and Framingham arrived, almost 400 new men, bringing the total force, including those hot on the trail of the British rear, to about 1,300.19 Some militia positioned behind the sparse young woods on the slopes of Brooks Hill just south of the road, others took cover along the extended stone hedge that lined the south roadside, while many more hopped this and the wall opposite to take cover in the north fields, together hoping to ambush the retreating redcoats with deadly crossfire. But their surprise was ruined. The British lights, deployed again from the main body, swarmed in small parties through the roadside woods and came upon the concealed Americans.

The firefight was instantly sharp. The woods on all sides billowed with white smoke as scattered shots came from both militia and British flankers. The grenadiers on the road gave a volley or two, but the dispersed lights along the roadside fired scattered shots at will. The lights successfully pushed the Americans back and dislodged them, but not before the Yankees gave a few scattered and deadly crossfire shots to the column of grenadiers on the road. Both sides fought fiercely, but the Americans were at last forced to withdraw. Perhaps another eight or more British were killed, with dozens more wounded, one of whom tried to march away with the column, only to collapse along the roadside, where his fleeing comrades left him.20

The main column continued its retreat under only scattered and distant potshots, while the pursuing Yankees took to the hills and pastures to get ahead of the column yet again. The eastward road took the fatigued British column past small Tanners Brook, also known as Elm Brook, and then climbed a gentle slope to a broad, flat, and wooded mound, where it turned northward to follow the mound’s edge. After traveling only a short distance atop this mound, the road turned again sharply eastward through a wooded area.

Among the militiamen hiding at that sharp curve were Maj. Loammi Baldwin and his three Woburn militia companies, about two hundred fifty men. They had first come onto the main road ahead of the British near the open space of Tanners Brook. But Baldwin knew better than to go head to head with the British, so he opted to move up the road and find a place to take cover. The sharp curve was the perfect opportunity for his ambush. As he and his men sat there waiting, they were joined by militia pursuing from Concord, who had once more cut across the fields to get ahead of the British. When the British turned the sharp curve, the grenadier main body was caught in Baldwin’s snare—the Americans immediately fired from behind trees and boulders. This firefight at the Bloody Angle (or Curve), as it has since been called, was the next intense clash. The grenadiers gave a volley from the road, while the light infantry swarmed once more into the deadly woods, braving sniper fire to again dislodge the Americans. But before the British flankers could do their job, the militiamen quickly fired and then retreated eastward, hoping to lay a second ambush.21

The beleaguered British pushed their way through the ambush, leaving “many dead and wounded and a few tired.”22 Perhaps eight were left dead there, many more left struggling with agonizing wounds.23 The British next passed the Hartwell Tavern, which still stands, descended the small mound and soon passed the site of Paul Revere’s capture. As they pressed eastward, they were continuously harassed by sporadic, scattered shots from snipers unseen.

The road they followed turned once more, from east to slightly southward to circumnavigate another mound on the British left. There they met with Capt. John Parker and his Lexington militia, now together in full force of about one hundred forty men, concealed upon those northern slopes or across in the fields to the south.24 As the British moved into Parker’s trap, his men let loose with an onslaught of deadly crossfire, this known since as Parker’s Revenge. The British received heavy fire and several more casualties, all from hidden militia assailants who fired and then retreated before the weary light infantry flankers could swarm the hill to dislodge them.25

The constant work of rooting out concealed Americans from behind hedges and walls was quickly exhausting the light infantry. Now, to add to their exhaustion, they were running short on ammunition. What was worse, they had not even reached Lexington, let alone the many miles that stood between them and Boston. Though the grenadiers had fired less, and so found in their cartouche boxes more ready-made cartridges than the light infantry, even they began to worry that the countryside might soon wipe them all out.

All the British could do was plow forward. They road turned again eastward and around a slope called the Bluff. From there they could see the next mound, Fiske Hill, which they looked upon with utter dread. Each major mound thus far had been crawling with rabid militia. Sure enough, hidden militia on the Bluff to their left opened up with a new barrage. These were probably Parker’s Lexington men, who had fallen back along the opposite side of that slope, ready to send another round or two into the escaping redcoats. The British flankers rushed up the slopes to disperse them, but the militia withdrew ahead of them and headed eastward, continuing to harry the British as they did so.

As the Bluff on the British left dissolved away into a flat valley, the road next took the British slightly northward around Fiske Hill to their right. Hiding there on Fiske Hill was the Cambridge militia, another almost eighty men, and they too opened fire. This, tied with Parker’s Lexington men still harrying the British left, produced some of the worst crossfire the British had yet found themselves in. Many of the British, frantically trying to reload, discovered they were down to their last shots. The slopes and trees thundered a hailstorm of lead musket shots all around them—all the woods seemed to be belching forth white smoke. The intense crossfire turned the road into a bloodbath. The “light companies were so fatigued with flanking they were scarce able to act, and a great number of wounded scarce able to go forward, made a great confusion”.26

Major Pitcairn, who had either daringly remained on his steed or climbed back atop it, raised his sword as he galloped up the boulder-strewn Fiske Hill to lead a charge of his dejected and exhausted light infantry. The lights struggled as heavy fire mowed many of them down, but Pitcairn rode back and forth among them, sword drawn high, weaving his horse between the trees and the constant whizzing balls of the crossfire, commanding and urging the lights forward.

Several Yankees at once recognized Pitcairn as an officer. Hiding behind a pile of wooden rails, they waited for a clear shot through the trees. Then they got it! They sprang out from their hiding place and fired scattered shots. But they were too zealous, for all their shots missed. Pitcairn must have heard the balls whiz by. His horse certainly did. The steed bucked wildly, flinging Pitcairn to the ground before taking off in fright through the crossfire and directly toward Pitcairn’s assailants, leaping the rail wall they had hid behind and running off. Pitcairn got up, sore from the fall, but unscathed. The Yankee snipers desperately tried to reload, but the British lights swarmed them, likely slaying one or two by musket ball or bayonet.27

Even as the light infantry stormed Fiske Hill, the grenadiers gave their own scattered volleys from the road. Though the Americans “kept the road always lined and a very hot fire on us without intermission; we…returned their fire as hot as we received it”.28 Somewhere along the way, perhaps here, Lieutenant Colonel Smith received a shot in the leg. Whether he dismounted because of this shot, or had done so earlier so as not to be such an easy mark, he walked with his men the rest of the way and was apparently able to do so without much trouble despite his wound.29 Lieutenant Sutherland, injured and carried helplessly along in a wagon, was around here unseated from his makeshift gurney. He wrote that his “Chair broke down there & my horse was shot thro’ the Shoulders.” He seems to have ridden the rest of the way on horseback, sitting as low as he could to avoid the deadly crossfire.30

About this time, a British soldier fled the skirmish and deserted his comrades to take refuge at a house nearby, possibly the home of Ebenezer Fiske himself. As the soldier approached the home, so did a stray militiaman. When the two spotted each other, they instantly raised their muskets and fired with deadly effect, felling one another instantly on the spot.31

The British expeditionary force managed to again drive through the deadly attack and so rounded Fiske Hill. From there they still had more than a mile to even Lexington Green, with about sixteen miles yet to Boston. With the confusion of this latest skirmish, and with a dozen or more left dead or wounded, the men utterly spent, many without ammunition, and many officers wounded, discipline finally gave way, “so that we began to run rather than retreat in order.” The orderly march became a terrible rout eastward.32

The few able-bodied regular officers remaining attempted to stop this mad rush “and form them two deep, but to no purpose, the confusion increased rather than lessened”. At last, the officers pointed their own fusil muskets, bayonets fixed, at their own men, threatening to kill them if they did not heed their orders. At this, the pell-mell retreat finally halted, even under intense musketry, leaving the soldiers caught between a mob of officers brandishing bayonets and swords ahead, and a horde of vicious and deadly militia that continued to envelop them from the rear and the flanks. “Upon this they began to form under a very heavy fire”.33

The militia horde, now perhaps 1,800 or more, in their browns and their whites of homespun clothes, relentlessly hounded and harried the fewer than 790 redcoats.34 Embattled Lieutenant Barker bemoaned, “their numbers increasing from all parts, while ours was reducing by deaths, wounds and fatigue, and we were totally surrounded with an incessant fire as it’s impossible to conceive, our ammunition was likewise expended”.35 Now each fallen redcoat was left to his own fate. Some dragged themselves up and continued as best they could, only to be captured as the horde engulfed them; others gave up the fight and lay defeated along the roadside. Many others would die of their wounds in the road’s red mud mixed with the effusion of blood.

The British column, once re-formed, charged forward at double time under heavy fire and desperate exhaustion toward Lexington. Most of the light infantry had indeed expended their last shots and thus could provide no flanking cover. They pulled in close to the main column, retreating under the protection of the grenadiers who still had a few (but not many) shots left in their cartouche boxes. They must have cursed the order to carry only thirty-six shots per man.

When Lexington Green came into sight, the brokenhearted British prepared for another ambush. The last hill before the Green, Concord Hill, lay on the British left, and from there a small but sizable gaggle of militia gathered to rain down musket balls as the British passed.36 But the beleaguered troops rushed by, hoping against hope they might flee from their pursuing enemies and make it yet to Boston.

As the desperate British charged along the south road that defined Lexington Green, all was eerily quiet. They feared the worst, yet passed the triangular Green without incident and continued eastward, closely pursued by the relentless militia. But the defeated soldiers hung their heads low as some computed they still had nearly sixteen miles to Boston.

Suddenly: ahead of the British, on the heights commanding both sides of the road, two deafening booms thunder-cracked and echoed across the hills. These were two small but lethal 6-pounder field cannon, which blasted their iron round shot toward the British. Perhaps some of these hopeless redcoats looked up only at this moment to see death head on, hearing the Doppler effect, the increasingly high pitch, as the heavy balls whizzed toward them…and then overhead!

The balls sailed past the retreating British and into the hounding militia horde behind, perhaps ripping to shreds one or two of them and instantly scattering the rest.

As those hopeless British now all raised their bleak and harrowed faces and gazed forward, they beheld a sight both marvelous and awesome. Ahead, in line formation across the entire expanse at the base of those heights: the entire British 1st Brigade (the 4th, 23rd, and 47th) and the entire Marine Battalion—about one thousand fresh British soldiers, plus their officers. Atop two separate heights, maybe two dozen dark-blue-coated artillerymen surrounded their two fieldpieces, which they gracefully and rhythmically worked—almost danced around—as they reloaded. What awe those downtrodden soldiers must have felt, to gaze upon the nearly 1,150 men in total, their brilliant red coats, their prestigious standards flapping in the wind, Brigadier General Lord Percy at their head, standing with his men (not mounted on a horse), the thunder as the two cannon roared once more, unleashing two more shot that sailed over the British and into the scattering militia.37 The British expeditionary force had been routed, mangled, and slaughtered, but for the first time that day, they must have felt victorious. The pursuing militia, however, must have felt loathing as they watched their prey slip from their clutches.38

The British were saved! With a shot or two more from the two British 6-pounders, the militia horde fully dispersed, allowing the dogged British expeditionary force to safely pour past the 1st Brigade’s lines and take refuge in the fields beyond. They “were so much exhausted with fatigue, that they were obliged to lie down for rest on the ground, their tongues hanging out of their mouths, like those of dogs after a chase.”39

The British reinforcement had arrived. And the whole tenor of the battle was now about to change.

• • •

It was the greatest sight many of those men ever beheld. The British reinforcement, which Lieutenant Colonel Smith had sent for before his march into Lexington that dawn, had now arrived. Lieutenant Barker later wrote, “we had flatter’d ever since the morning with expectations of the Brigade coming out, but at this time had given up all hopes of it, as it was so late.”40

It was now about 2:30 p.m., and the reinforcement was indeed later than planned. The first blunder had occurred when General Gage sent orders to the 1st Brigade to be under arms at 4:00 a.m., but as the brigade major was not in his quarters when the orders arrived, they were left for him on his table and remained unseen. When Smith’s courier arrived to request reinforcements at 5:00 a.m., Gage debriefed him and then wasted time inquiring why his 1st Brigade was not already prepared to march. Finally, at 6:00 a.m., Gage issued new orders that the troops muster on Boston Common at 7:30 a.m. Due to a second blunder, the orders for the Marine Battalion were left at Major Pitcairn’s quarters with his aides, but Pitcairn was on expedition, and the aides failed to inquire on their immediacy, and so these too were left unseen. Thus, when the 1st Brigade paraded at 7:30 a.m., the marines failed to show, and it took another hour to rectify the mistake. This, plus other delays, caused the reinforcement to not depart from Boston until 8:45 a.m.41

The commander of the British reinforcement was Hugh, Earl Percy, and at thirty-two, he was the eldest son of the Duke of Northumberland. Though he appeared sickly, with his thin and bony features, his protruding nose and his body showing signs of degradation from the gout, he had swagger. (Or was that sprightliness in his step from the brandy he kept in his canteen?) He was popular among his troops because they felt greatly honored to serve under a man of such prestigious nobility.42 Lord Percy had come to the colonies in July of 1774 as the regimental commander (colonel) of the 5th, but had almost immediately been promoted to brigadier general (in the American service only) and given the charge of three regiments—the 1st Brigade.

After he had time to appraise the worsening situation in America, he wrote candidly to a friend, “Our affairs here are in the most Critical Situation imaginable; Nothing less than the total loss or Conquest of the Colonies must be the End of it. Either indeed is disagreable, but one or the other is now absolutely necessary.”43 He had written that letter many months prior to this day, little expecting he would play such a pivotal role in the “disagreable” affair.

Rather than cross the Charles River by boat, Percy’s reinforcement marched the longer ground route through Boston Neck and Roxbury to the Great Bridge that crossed to Cambridge, almost an extra four and a half miles.44 When Percy’s advance scouts, some miles ahead, arrived at this bridge, they discovered the rebels had removed the planks. But the Yankees, rather than stealing the planks away, merely left them stacked on the opposite side. Among the British scouts was the engineer Capt. John Montresor, who had gone ahead expressly to investigate the bridge. He had with him four volunteers, whom he sent across on the stringers to collect the planks. Together they were able to quickly rebuild the bridge deck to sufficient strength, and Lord Percy had neither delay nor trouble in getting all his men and their two cannon across the Charles River.45

As Percy’s reinforcement moved westward from Cambridge to Lexington, “few or no people were to be seen, and the houses were in general shut up.”46 The towns were so uncannily quiet that Percy’s gut told him that upon their return, “we shall be fired at from those very houses.”47

Portrait of Hugh (Lord) Percy, Brigadier General and Earl (in 1775), later Second Duke of Northumberland (c. 1788) by Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828). Courtesy of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta.

Fortunately for Lord Percy, he received timely intelligence from one of Smith’s own men. Lt. Edward Gould, slightly wounded, had retreated ahead of the main expeditionary force from Concord, driving the chaise in which he ferried poor Lt. Edward Hull, who suffered from three terrible and life-threatening wounds. After passing Lexington unmolested, Gould and Hull had come upon Percy’s reinforcement, marching in column, braced by two strong fifty-man van and rear guards. Percy conferred with Gould and, from the intelligence the young officer provided, the brigadier acted accordingly, deploying many more flankers and probably only then ordering his men to load and ready their muskets.

Percy also sent Lt. Harry Rooke of the 4th Battalion on horseback express back to Boston to inform Gage of the situation. Rooke’s ride was Paul Revere’s in reverse, with Rooke forced to take detours to avoid the American forces. These delays put Rooke in Boston sometime past four o’clock that afternoon. To cover the British return and fend off the defenders of the countryside, if need be, Gage placed his 2nd and 3rd Brigades under arms and ordered to Boston the bulk of the 64th Regiment from Castle William.48

Meanwhile, wounded Gould and Hull left Percy and made their way onward toward Boston, only to be captured near Menotomy. As for Percy, armed with his new intelligence, he continued his advance through what he now knew to be hostile territory. When he heard the distant and sporadic musketry ahead, he promptly ordered his men into line formation and his cannon to take up positions on the heights. Then, he waited the few minutes for the retreating British to flee into his open arms.49

• • •

At about the same time Percy’s reinforcement was mustering on Boston Common, anxious Dr. Joseph Warren, undoubtedly awake, received a messenger at his home on Hanover Street. Who this messenger was is unknown. He could have come from outside the town, since by dawn both Boston Neck and Charlestown Ferry were again open for business. Most likely, the messenger was a Bostonian who had observed Percy’s reinforcement muster on Boston Common. In any case, the messenger brought rumors of war.

Dr. Warren probably grabbed his fusil musket before giving charge of his patients to his senior resident apprentice, Dr. Eustis, and then mounted his horse and rode at once for Charlestown Ferry.50 There he encountered the excitable and disconcerted John Adan of Boston. Warren offered his encouragement: “Keep up a brave heart! They have begun it—that either party can do; and we’ll end it—that only one can do.”51

The ferry landed him in Charlestown about eight o’clock that morning, where Warren found the town in confusion and turmoil over the rumors of war to the west. Everywhere he looked, he saw the inhabitants packing their goods and preparing to flee, fearing for their safety once the British returned. Warren navigated the chaotic streets and made his way to meet with local Whigs there. Perhaps one of his stops was the home of militia leader Col. William Conant, for Warren was still uncertain whether Revere had crossed safely the night before.

The doctor spent near two hours in the town talking with various leaders, gathering what information he could. Finally, at close to ten o’clock, he rode off for Menotomy. His destination was the village’s Black Horse Tavern, belonging to Mr. Ethan Wetherby, where the Committee of Safety had held a routine meeting the day before. Warren had not attended, but he knew they were due to meet again this morning. Moreover, he knew this morning’s meeting would be anything but routine.52

Along his path, Warren found all the houses shut up and seemingly deserted. All was hauntingly quiet until he reached Menotomy, where people were hurrying about and discussing the news.53 He made straight for the tavern.

No record seems to exist of that emergency meeting of the Committee of Safety, but with the Provincial Congress not in session, almost total control and decision-making authority fell to these few men whose special charge was governing the militia.54 John Hancock, the committee’s chairman, was escaping to Woburn, so the members looked to Warren as their acting chairman. Among those at that sub-rosa meeting was committee member and militia leader Col. William Heath.55 Heath did not stay long, but rode off to Watertown to meet the militia there.56

The remainder of the committee discussed what little they knew of the news of day, before talk quickly turned to which side had fired the first shot. It was too early to know the answer to that (and indeed we still do not have it), and yet, though none of them had witnessed the Skirmish of Lexington, everyone there gave much speculation on the matter. Dr. Warren and the other committee members, indeed all of the leading Whigs, were careful to conduct their resistance to British policy in a legally justifiable way. They could only hope then that the British fired first, thus justifying every other action the Americans would take that day as necessary, defensive measures against a tyrannical government.

While the committee discussed their business, couriers rode to and from Menotomy, bringing in new intelligence and sending out information to the various but disorganized militia companies streaming in from all directions. One of those was Israel Bissel, who was “Charged to Alarm the Country quite to Connecticut, and all Persons are Desired to furnish him with fresh Horses, as they may be needed.”57

Sometime after the committee had convened, there was a tense moment in the tavern, and in fact in all of Menotomy, as Percy’s reinforcement approached the village. The people all rushed indoors, and Menotomy instantly became a ghost town as the British marched through. This was the first time Warren had seen the British troops since they had departed from Boston.58 It would not be his last.

• • •

East of Lexington Green, Lord Percy’s reinforcement maintained their line formation across the road and at the base of the heights there, while Lieutenant Colonel Smith’s expeditionary force re-formed in safety behind.59 As for the Americans, without any sort of unified commander, the independent companies only somewhat regrouped as laggards finally rejoined the horde and as detached platoons found one another. But as more Yankees poured in, others departed, seeing themselves as mere volunteers and free to come and go as they pleased. Some left having seen enough blood, others having spent their last bullets, many more feeling they had performed ample service and expecting the fresh troops coming in to fill their places.

The colonial officers could do little to keep their men from departing. Since their own men had elected them to their station, they had very little real authority, particularly if they hoped to retain their men’s favor and thus retain their officerships. Because of this independency and volunteerism, knowing the number of militiamen present at any one point is impossible. While perhaps 1,800 militia had engaged the British up to Lexington Green, many now left in droves, particularly upon seeing the strong British reinforcement led by Lord Percy. The American force slowly dwindled now to maybe as few as 1,100.60

Even so, all the neighboring hills were alive with small militia parties. They inched to just within firing range of the British, took cover behind trees and rock hedges, and gave an occasional scattered volley without effect. The British held their position and answered the Yankees with their own occasional volley, also without effect.

Lord Percy’s job was now to protect Smith’s weary detachment and allow the men a brief respite before they marched again eastward. He first ordered Smith’s men to fall back farther to the Munroe Tavern, where they could tend to their wounded. Percy then looked to secure his own defensive posture, ordering out strong parties to guard the flanks of his main battle line from the many militia now dotting the hills and pastures. At least three houses on those outskirts of Lexington blocked the battle line and the artillery’s clear view of the entire kill zone. The encroaching militia could easily use those nearby houses for cover, so Percy ordered out flanking parties to torch them. Deacon Loring’s house was one of those sacrificed. Flankers set fire to its gables, then shattered the windows and threw in their torches. As the blaze quickly spread into a great conflagration, the flankers pulled down the adjacent stone walls, sending puffs of dust into the air to mingle with the massive columns of smoke pouring from the burning home. Lord Percy watched with satisfaction as the flank guards torched the two other homes and perhaps an adjacent barn and shop as well.61

As the homes polluted the air with their billowing smoke, British flanking parties darted from cover to cover, firing sporadic scattered shots to keep the encroaching militia at bay. Some of these flankers came from the 23rd Regiment, which seems to have formed the British left and had positioned itself along the gentle hills south of the road. Their adjutant, 1st Lt. Frederick Mackenzie, later wrote, “the Rebels endeavored to gain our flanks, and crept into the covered ground on either side, and as close as they could in front, firing now and then in perfect security. We also advanced a few of our best marksmen who fired at those who shewed themselves.”62

Whenever the British muskets failed to disperse the clusters of militia, the two 6-pounders roared to life to fire off a ball or two. The greatest throng of militia remained near Lexington Green, having halted there when they gave up pursuit of Smith’s expeditionary force. Many of them gathered around the meetinghouse that doubled as the town’s church, where some went inside to resupply their powder and balls.

The British fired their cannon several times at this crowd. One ball whizzed not two yards past Maj. Loammi Baldwin of Woburn. He immediately retreated behind the meetinghouse, but had no sooner darted behind it than a second ball smashed through the church itself, flying through the front wall, soaring over its pews, and whizzing out the back side just inches from Baldwin’s head, terrorizing him and covering him with splintered debris. He wisely determined to find better cover and so headed north, past the Green, and laid in a meadow where he “heard the balls in the air and saw them strike the ground.” In the coming propaganda war, some Americans would cry foul that an artillery shot had crashed through the town’s church. But by housing weapon stores, the church was no longer protected under the rules of war.63

If some British soldiers wondered why their artillery pieces did not fire more frequently than they had, they soon discovered the answer. Ensign Lister learned that the pieces only had what rounds they could carry in their small carriage side boxes. This was twenty-four rounds apiece, though Lister, unfamiliar with the particulars of artillery, imagined they had but seven. Lt. Col. Samuel Cleaveland, commander of the Royal Artillery in Boston, had prepared a wagon with 140 extra rounds for Percy. However, despite the insistence of the excitable artillery commander, Percy refused it on the grounds that a wagon train would cause him undue delay in his march.64 There are unconfirmed stories that Gage sent two wagons after Percy, but because they were lightly guarded, the rebels captured them in Menotomy.65

As the standoff east of Lexington Green continued, both sides received refreshments. The Americans received theirs on the Green itself, provided by both the neighbors and Buckman Tavern. The British received theirs as they dressed their wounded at William Munroe’s Tavern along the road southeast of their main battle line. Left in charge of the tavern was lame John Raymond, who gave to the British whatever they needed. Munroe’s Tavern has sometimes been given the misnomer of Percy’s headquarters, though the British were hardly there long enough for it to be considered such. In fact, Percy perhaps never set foot in the tavern. Rather, it seems that only Smith and his exhausted expeditionary force gathered on its grounds.66

Ensign Lister, wounded near Meriam’s Corner, was among the British receiving much-needed medical care. Mr. Simms, surgeon’s mate of the 43rd, extracted the ball from Lister’s right elbow, “the Ball it having gone through the Bone and lodg’d within the Skin”. Mr. Simms bandaged Lister up, but could do nothing for his loss of so much blood. Lister would have to make his way along the march as best he could.67

In this brief intermission of the daylong battle, the poisonous news of the “scalping” at Concord’s North Bridge transfused to all the troops, even to Lord Percy. Some of the rumors now claimed that the Americans planned to scalp or otherwise mutilate all soldiers left dead or wounded. The British looked upon the Yankees with newfound contempt as rage spread like wildfire across the long line of redcoats.

Finally, after forty-five minutes of dangerous but necessary delays, the time near 3:15 p.m., Lord Percy observed, “it began now to grow pretty late, & we had 15 miles to retire, & only our 36 rounds”.68 Accordingly, he gave a flurry of orders to his various subordinates to make ready the march back to Boston. He ordered the artillerymen to limber their two guns, with which they probably had four horses each.69 He ordered the 23rd on the south side of the road to form the rear guard. The 23rd immediately sent out flankers and marksmen to line the walls and cover ahead while the main 23rd Battalion moved up the low hills behind them and formed a new line with a better commanding view, there to protect the rest of the British as they formed into one massive column behind.70

The vanguard was organized, consisting of the embattled expeditionary force (first the exhausted light infantry, followed by the weary grenadiers), flanked by five companies of the 4th Regiment on the right, “where most danger was to be apprehended”, and three companies of the 47th on the left, thus encapsulating the expeditionaries within bodies of fresh troops. The remains of the 4th and 47th served either as flankers or in column directly behind the vanguard. The artillery seems to have marched midway down the column, followed by the marines. Once the column fully formed about half an hour later, the order was given to march, and the column began to move.

The 23rd, still on the heights and serving as the rear guard, fell back from their line formation and formed again in column behind the main body. Together the combined British force of almost 1,900 men departed Lexington, leaving in their wake three smoldering homes with only their brick chimneys still standing.71

As the British began their long march eastward, their fifers and drummers started to play that mocking tune “Yankee Doodle”—“by way of contempt”, the militia thought. It served only to further incense the Americans. The bloody running battle was far from over.72

• • •

There was great commotion among the Americans as the British pulled out. One grenadier of the 23rd wrote, “As soon as the rear Guard began to move, the Rebels commenced their fire, having previously crept round under cover, and gained the walls and hedges on both flanks.”73 Ensign De Berniere observed, “the rebels still kept firing on us, but very lightly”.74 Lieutenant Barker thought the first two miles were “pretty quiet”, until they “began to pepper us again…but at a rather greater distance.”75

There was indeed a brief lull in the combat along the Battle Road, but it was not because the Americans had given up. Quite the opposite: they were making their way through pastures and woods, taking long, circuitous paths to gain the advantage ahead of the retreating British. Most of the Americans attempted to encircle on foot, but some had the benefit of horses. These rode ahead of the column, dismounted, and secured their horse behind some cover, then daringly “crept down near enough to have a Shot; as soon as the Column had passed, they mounted again, and rode round until they got ahead of the Column, and found some convenient place from whence they might fire again.”76

Fresh American forces were continually coming in, guided by the sounds of the musketry. Soon even the van began taking heavy fire “from all quarters, but particularly from the houses on the roadside, and the Adjacent Stone walls.”77 Lord Percy had deployed very strong flanking parties. Flanking was ordinarily a job reserved for the light infantry, but since the lights had all participated in the expeditionary force and were now spent, platoons were selected from among the main battalion companies to take on this burden. As his column marched along, Percy found these flanking parties “absolutely necessary, as there was not a stone-wall, or house, though before in appearance evacuated, from whence the Rebels did not fire upon us.”78 Just as Percy had anticipated, each apparently empty house was now a bunker for snipers.

The continuous but scattered colonial fire grew ever more effective. Several troops were picked off by enemies unseen, falling dead or wounded along the road. The flanking parties, enraged by an ungallant enemy that fired while in hiding, and remembering the rumors of the scalping, began to storm every house along the way in turn, ready to put to death all inside.

As British casualties mounted, the dead were left along the roadside, but the wounded, fearing a scalping should they be left behind, struggled to stay with the march. Lieutenant Colonel Smith, with his wounded leg, had apparently given up his horse, but now begged a replacement from a marine officer. Dazed Ensign Lister, stumbling along as best he could, exhausted from the earlier work and light-headed from the loss of blood at his shattered elbow, begged of Smith to borrow the same horse, which Smith graciously gave him. Lister was not faring well, but the horse helped. Others nearby eased his burden too. One soldier, who still had in his haversack beef and a small biscuit, generously gave Lister half his meager meal—no more than a mouthful for each of them. A grenadier in Lister’s regiment took the ensign’s hat, broke ranks from the column, filled it with water at a horse pond, and then rushed it back to Lister. The parched Lister thanked him before gulping down the muddy water from his own hat. Lister’s horse carried him along for about two miles, but as the militia parties gathered in increasing numbers around the flanks and the van, balls began to whiz by his head. Suddenly, he felt walking was the safer bet, even in his dire condition. He struggled to dismount and then led the steed along the march. Deadly militia fire continued to rake the column, despite the hard work of the many British flanking parties. So Lister adapted his defense accordingly: “as the Balls came thicker from one side or the other so I went from one side of the Horse to the other for some time”.79

The roadside crossfire continued to grow ever more ferocious, leading the remaining mounted officers to all prudently give up horses. And in the same manner, all of these horses became walking shields for the wounded, who clung to the saddles and stirrups for support, switching from one side or the other as the intensity of the crossfire shifted. Inevitably, a shot finally hit one of these shield horses, killing it dead on the spot. The heavy beast’s corpse instantly collapsed, causing a ripple down the column as the troops attempted to surpass it.

This particular horse had carried one wounded man draped on its back and shielded three other wounded hanging by its side. These all begged Lister to let them join him behind his horse, to which he readily agreed, and soon after he gave it wholly to their use. Others overcrowded the few chaises and wagons that had come with wounded from Concord. Still others piled onto the two horse-drawn artillery carriages and their limbers, clinging to the side boxes to hold on. “It was a very fatiguing march, and not being prepared with any conveyances for our wounded, it required the exertion of everybody to bring them off. The carriages of the guns were so loaded with wounded men that they could scarcely be fired”.80

The running fight soon approached the sparse village of Menotomy. There the local militia lay in wait, joined with a considerable force of men from distant Danvers, Beverly, and Lynn, and from the nearer Medford and Malden, almost nine hundred men, positioned on the heights just north of the village’s center.81 All were under the command of Col. William Heath, who had returned to the village only a short time earlier. Joining him was Dr. Joseph Warren, who left the committee at Black Horse Tavern and would stay with Heath throughout the coming fight. Heath’s force provided the closest semblance to an organized attack by the militia that day, but only in that quarter, for, of the pursuing militia horde and those attempting to harass the British flanks, they were still every one of them their own commander. The British were marching into a trap. Even if Lord Percy knew it, there was little he could do but march his men forward.82

With the militia horde closing in, a host still near 1,100 strong, the inexperienced British soldiers carelessly threw their shots away, emboldening the militia to draw closer still. The militia swarmed from all sides, but as Lieutenant Mackenzie observed, “they did not shew themselves openly in a body in any part, except on the road in our rear”. Just as the British were coming upon Menotomy, Percy temporarily halted his retreat, ordering the artillery to unlimber and fire on the colonial horde. After the wounded soldiers crawled off the two gun carriages, the dark-blue-coated artillerymen unlimbered and prepared to fire with one of the few remaining shots left in their guns’ side boxes. At the same time, the main column’s rear guard fired a concerted volley or two into the pursuing militia. The rest of the column could do little but fire scattered shots at the ghostlike snipers along the rock walls, or as Mackenzie explained, “the moment they had fired they lay down out of sight until they had loaded again, or the Column had passed.” And sometimes the snipers relocated before firing again, giving the flanking companies tough work as they chased constantly moving, hidden targets.83

Once the artillery got their two pieces ready, they both fired their round shot, blasting into the militia horde, perhaps felling a colonial or two while temporarily dispersing the rest. However, it was the ferocious roar of the cannon that was the real weapon—not the shot. Many of the younger men in the militia, those not veterans of the last war, were unaccustomed to the din of battle and easily frightened away.

While the artillerymen quickly re-limbered their cannon and the wounded crawled back on their carriages, the British column, ready to advance once more, saw Colonel Heath’s new body of about nine hundred descending from the nearby northern heights. Lord Percy no sooner got his men back into the march than Heath’s militia reached the roadside ahead. The British were now surrounded, but Percy had no intention of surrendering. Heath’s men took cover behind and inside the houses, took aim on the British vanguard, and opened fire.

• • •

Here, in the half-mile approach to Menotomy center, the day’s bloodiest battle quickly grew into its fiercest as well. From the road ahead, Heath’s militia began their deadly onslaught, pouring musket balls into the British vanguard and slowing their march to a crawl as they struggled to counter the attack. In turn, the entire British column began to compress, and the horde of Yankees pursuers seized this opportunity to close in around their prey from the rear. Rev. Ezra Stiles would describe the militia strategy as “dispersed tho’ adhering”—that is, the militiamen were not one body but scattered, yet they kept close on the British. The Yankees soon had the embattled redcoats enveloped in what Percy would call “an incessant fire, wh[ich] like a moving circle surrounded & fol[lowe]d us wherever we went”.84

One British officer there described Menotomy village as “a number of houses in little groups extending about half a mile”. Now every house became its own battleground, with militia swarming into it for cover and firing from the windows. Percy decisively ordered his flankers to storm those houses and kill all inside. The enraged soldiers were only happy to comply, anxious to avenge their justice on what they thought were contemptible Americans who ungallantly assailed them while hiding and who had allegedly scalped their wounded comrades. Driven by their rage, fear, and adrenaline, the intrepid soldiers forced their way toward the first houses, plowing through the heavy fire that erupted from each window even as it picked off several of them. The defending Americans fought with equal rage, spurred on by the tidings of the shots at Lexington and Concord, and their contempt for Percy’s burning of homes outside Lexington. The American defenders inside didn’t try to flee or hide until the British flankers at last reached the first homes, but the British slaughtered many of the Americans before they could escape.85 As echoed by several British officers there, Mackenzie wrote, “Those houses would certainly have been burnt had any fire been found in them, or had there been time to kindle any”.86

When the house-to-house fighting approached the home of Jason Russell (it still stands today), the lame and barely ambulatory fifty-eight-year-old escorted his family into the neighboring woods. There he left them, and he returned to his home, where he hobbled about his porch, stacking a pile of shingles before his front door to serve as a barricade. A neighbor, Ammi Cutter, urged him to flee, but Russell replied, “An Englishman’s home is his castle,” or so tradition says. The neighbor took his own advice and fled, but encouraged by the old man’s spirit, more than a dozen militia joined Russell at his makeshift breastwork.

When the fierce battle at last reached his doorstep, the militiamen fired a volley and then retreated inside. Russell tried to follow, hobbling to go inside quickly, when British flankers opened fire, felling him with two bullets. He was not yet dead, so one of the redcoats plunged his bayonet into Russell’s chest, though before the soldier could give that horrible wrench that would ensure Russell’s demise, other soldiers thrust their bayonets into the poor old man, finally killing him.

The flankers then stormed inside Russell’s home, where a short but vicious melee ensued. The Yankees killed one regular, but the British slaughtered eleven Americans by bayonet (who had no bayonets themselves with which to fight close-quarter combat). The few Yankees who remained fled to the cellar, and the redcoats quickly followed until the first soldier was killed, likely by musket, his corpse tumbling down the stairs. The Americans then yelled that any other that dared to come down would suffer the same fate. So the British gave up the fight, grabbed a few pieces of plunder, and returned to the fight outside.87

On the road, the fighting was equally intense. The whole blood-spattered street was one cloud of white gun smoke, which helped provide cover as the British main column slowly pushed through the hail of crossfire, stepping over their dead and wounded and taking heavy casualties as they did so. Even those exhausted light infantry and grenadiers that had marched out with Smith, who now stood in the vanguard protected by the reinforcement, were again under an incessant fire nearly as severe as that on the rear guard. If any of those expeditionary force soldiers still had ammunition left in their cartouche boxes, they ran out of it here in Menotomy. Perhaps some of their neighboring battalion soldiers shared some of their own ammunition.88

Though the whole of the British were surrounded in a circle of fire, they slowly pressed on at what must have felt like a snail’s pace. Even under such heavy crossfire, the artillery awkwardly fumbled to add to the fight as well, blasting at least one or two rounds into the thick militia biting at the British rear.

Farther along, some of the Danvers militia, darting into a better roadside position from which to harass the British, hurriedly built a barricade of stones and lumber. As these ill-experienced Yankees did so, they quickly found themselves caught between a large British flanking party and the main column. Though the Danvers men had hoped to help pour a crossfire into the main British column, they instead found themselves trapped in one. The British flankers fired viciously into these Danvers men, seven of whom fell dead or dying, with perhaps a dozen more wounded. The British flankers then charged with bayonets, maybe running a few militiamen through, while the lucky rest fled pell-mell from the roadside.89

In the heart of this action, Dr. Joseph Warren kept constantly near Colonel Heath, helping to encourage the men as he likely fired his own fusil musket. One colonist told of Warren’s service: “he appeared in the field under the united character of the general, the soldier, and the physician; here he was seen animating his countrymen to battle, and fighting by their side; and there he was found administering healing comforts to the wounded”.90

Though the musketry grew severe from both opponents, Warren was in the thick of it. One British shot whizzed so close by Warren’s ear that it struck the pin out of the hair of his earlock, letting his neatly tied hair fall out of place. Heath saw it and looked at Warren to ensure he was okay. The good doctor may have paused for a moment to take a breath, but he remained relentless and undaunted, and likely fired several rounds into the British himself.91

Also in the heat of the battle was eighty-one-year-old Samuel Whittemore. As the battle neared his home, he sent his family fleeing and then marched to the road with a musket, two pistols, and a saber. He took position along a stone wall, and as the British came near, he fired all three guns. Legend claims he killed one soldier and wounded two more before the British swarmed him, shot him in the head, beat him with the butt ends of their muskets and bayoneted him several times. Left for dead, he was later attended by Dr. Cotton Tufts, who gave the gloomy prognosis that it was useless to try to save poor Whittemore. Yet Whittemore recovered, not to die until the ripe age of ninety-nine.92

The close-quarter street fighting continued as the British tried to break through the ambush. Percy observed that “several of their men…[had] a spirit of enthusiasm…for many of them concealed themselves in houses, & advanced within 10 yds. to fire at me & other officers, tho’ they were morally certain of being put to death themselves in an instant.”93 A tradition says that one ball whizzed so close to Lord Percy that it sheared off a button from his scarlet coat.94

With the Americans continuing to engulf the British, the pursuing militia horde drew so close to the British heels that militiaman Dr. Eliphalet Downer found himself in close combat with a redcoat. The soldier lunged his bayonet at the doctor’s chest, but Downer parried the thrust and wrangled the musket from the redcoat, turned it, and lunged the soldier’s own bayonet into him with such force that the blade nearly passed out the other side, felling him on the spot.95

The flanking parties meanwhile continued their house-to-house search. At Cooper Tavern, two drunken but armed militiamen, middle-aged brothers-in-law Jason Winship and Jabez Wyman, stood drinking a liquor, beer, and sugar cocktail known as flip.96 They merrily and obliviously drank away the afternoon, derelict of their duty, when a flanking party stormed in. The bartender and his wife quickly vanished, leaving the drunks to be run through by British bayonets. The British soldiers then barbarously stabbed them multiple times more, before bashing their skulls in and splattering blood and brains on the walls and floor. Afterward, the barkeep Benjamin Cooper found the gruesome corpses and noted more than a hundred bullet holes in the tavern, an example of the ferocity of the fighting throughout the village.97

In other houses, flanking parties stormed in but found no one, though they were certain shots had been fired from inside. Lt. Frederick Mackenzie explained, “Some houses were forced open in which no person could be discovered, but when the Column had passed; numbers sallied out from some place in which they had lain concealed, fired at the rear Guard, and augmented the numbers which followed us. If we had had time to set fire to those houses many Rebels must have perished in them”.98

No house was safe. The British stormed into the house of Deacon Joseph Adams, whom they saw flee from the house as they approached, gutlessly leaving his defenseless wife and children behind. Three soldiers burst into the chamber of his wife, Hannah Adams, where she lay bedridden, recovering from giving birth just over two weeks earlier and scarcely able to walk. She cried out, “For the Lord’s sake do not kill me!” One soldier replied, “Damn you!” Another explained to his fellow, “We will not hurt the woman, if she will go out of the house, but we will surely burn it.” So Hannah crawled from her bed, having not walked farther than her bedchamber door since giving birth, and two of her daughters, young women, helped to dress her. One of the five Adams children, a nine-year-old boy named Joel, briefly popped his head out from under her bed. The soldiers saw him and told him to come out, to which the boy replied, “You’ll kill me if I do.” After the soldiers assured the boy they would not, he cautiously crawled out from under the bed and followed the soldiers around as they pilfered his home. Meanwhile, Hannah took her eighteen-day-old newborn and slowly but painfully made her way out the front door, where she took refuge in their small cornhouse (or corncrib) granary just outside. Once the soldiers were satisfied with their loot, they broke up some wooden chairs, lit the pieces by a fire in the hearth, and threw these torches about the home before quickly departing. Drawing on bravery obviously inherited from his mother’s side, young Joel acted swiftly, using a pot of his father’s home-brewed beer to extinguish the fire before it could spread, thus saving the house.99

Outside, the battle waged on. Menotomy was the deadliest skirmish either side fought that day, in large part because it was here that the Americans mustered their greatest numbers. Of an estimated 3,716 militiamen who served at some point throughout the day, probably no more than 2,000 ever gathered at one time. While this difference includes American casualties, mostly it is from the droves of volunteers who returned to their homes after they either had spent their ammo or otherwise given up the fight.100 In comparison, at about 1,900, the total British force was nearly equal in size, though given that the number included their many casualties and Lieutenant Colonel Smith’s depleted expeditionary force, it was maybe just half the effective American strength now.101 Still, the British inflicted serious casualties on the American force, so much so that Americans would later criticize Lord Percy’s tactics in the coming propaganda war.

Fair and less biased retrospection reveals that Percy was absolutely right in storming those houses one at a time. Unfortunately, in the literal fog of war that blanketed the village with thick, white gun smoke, the British officers lost control of their enraged and furious men, and a few of them committed atrocious acts. Indeed, just as we cannot excuse the North Bridge “scalping”, which served as the catalyst for this newfound British fury, nor can we excuse the few isolated acts of British barbarism, such as the butchering of the two drunks, which repaid the violence of that American atrocity many times over. But later spins in the propaganda war, as well as biased nineteenth-century claims, would heap unearned atrocities onto the British.102 For instance, Jason Russell’s death was gruesome, but he had fired on the British and so became a lawful target. His death is sad, but it was not an atrocity. In truth, the British soldiers generally fought admirably and honorably, as much as one can expect in a deadly ambush by an enraged countryside.103 Moreover, Percy’s mission was to get his people back to Boston. And swarming the houses to wipe out the snipers was tactically necessary.104

That said, the soldiers’ plundering of homes cannot be excused as merely isolated incidents. Looting was strictly forbidden by Gage and his officers, and the Americans were justified in their rage over such acts. As Mackenzie observed, “Many houses were plundered by the Soldiers, notwithstanding the efforts of the Officers to prevent it. I have no doubt this inflamed the Rebels, and made many of them follow us farther than they would otherwise have done. By all accounts some Soldiers who staid too long in the houses, were killed in the very act of plundering by those who lay concealed in them.”105

Lieutenant Barker gave a grimmer opinion in his diary a few days later when he wrote, “Our Soldiers the other day tho’ they shew’d no want of courage, yet were so wild and irregular, that there was no keeping ’em in any order; by their eagerness and inattention they kill’d many of our own People; and the plundering was shamefull; many hardly thought of anything else; what was worse they were encouraged by some Officers.”106

That a few (and it was certainly a very few) officers encouraged the plundering was not only shameful but unforgivable, and could they have been identified, they should have been given a harsh punishment. What was more, looting begot vandalizing and straggling. One wonders how many of the twenty-six British reported missing after the battle were in fact looters who tarried too long and were caught.107

Despite the ferocity of the battle, the British at last forced themselves through the massive ambush, leaving the dead and dying strewn across the path, dragging with them about ten prisoners taken in arms, a few of whom would be killed by friendly fire as the militia continued to send scattered shots into the British rear guard. (Other prisoners were apparently later released.)108

Though running low on ammunition, the rear guard 23rd Regiment was probably obliged to march backward to fight off the pursuing militia horde, with the regiment’s eight companies firing one at a time and then leapfrogging each other back toward the column, thus giving each company time to reload.109 They covered the rear admirably, but they paid a high toll in casualties, including their regimental commander, Lt. Col. Bery Bernard, shot in the thigh.110 Mackenzie, adjutant to the 23rd, heard the Yankees call out many times, “King Hancock forever.” Given the 23rd’s heavy burden and exhausting work to keep the horde at bay, Lord Percy ordered the 23rd to move up one place in the column, making the Battalion of Marines the new rear guard.111

The soldiers of the rear guard were not the only ones suffering from extreme fatigue—so too were the flank guards. As the British moved closer to the more populated area of Cambridge, the number of roadside obstructions grew. The Yankee militia took to the pastures and enveloped the rear guard, exerting relentless pressure. Consequently, the British flankers found themselves forced almost against the main column, unable to give wide flanking support.112

It took a steady drive on the part of the British, but soon they were through the thick of it. With the Skirmish of Menotomy behind them, the worst fighting of the day was over. But just down the road at Cambridge, the Americans had another ambush waiting. What the Yankees did not know was that Lord Percy had anticipated this next colonial ploy and had adjusted his strategy accordingly. This time, the Americans would be caught off guard.

• • •

The British marched the path from Menotomy to Cambridge with relative ease, though occasional harassing potshots continued incessantly. Ahead of the British was Watson’s Corner, a crossroads about a mile and a half northwest of Cambridge center.113 There the road forked, its southerly branch heading to town center, its northerly branch bypassing Cambridge and leading to Charlestown. As the British approached Watson’s Corner, they found waiting there yet another militia ambush. Some of these were undoubtedly men from Menotomy who had taken to the pastures and woods to circle around the British advance. Most were militia from the lower towns outside Boston: Roxbury, Brookline, Dedham, and Needham, almost nine hundred fresh men. This militia body stood on the northerly path at Watson’s Corner, blocking the fork toward Charlestown.114

Every Englishman there, be he American or Briton, naturally expected the British column to follow the fork south past Harvard College, across the Great Bridge over the Charles River, and then back to Boston via Roxbury—the standard land route, the one Percy had taken that morning. With this in mind, Colonel Heath had sent the 134-strong Watertown militia ahead to the Great Bridge with orders to again pull up the planks of the deck, barricade the bridge’s south end, and take up post to ambush the British when they arrived.115 The host of militia at Watson’s Corner meanwhile had orders to let the British pass, only to then follow the British as they came to the disassembled bridge, thus ensnaring the column in what was sure to be a more devastating ambush than even Menotomy.

Everyone, including Percy’s own officers, expected that the British would take the path to the bridge, but Lord Percy was too keen a tactician to fall for the Yankee ploy. He had probably considered as early as his march out to Lexington, when his advance scouts first found the bridge torn up, that it would be disastrous to return the same way. Instead, Percy decided to turn his column and take the fork toward Charlestown, and to plow his way through the nearly nine hundred fresh militia.116 Lord Percy gave the order, and the British vanguard turned at Watson’s Corner, straight for the vast American force. The Yankees were at first stunned by this change in direction…and then they opened fire.

Under assault, Percy halted his men and ordered his artillery to unlimber their guns. The British wounded once more rolled off the gun carriages, and as the bluecoats prepared their two pieces, loading some of the last rounds left in their guns’ side boxes, the weary battalion flank guards fired scattered musket volleys to keep the enveloping militia at bay.

With the firefight growing hot again, Maj. Isaac Gardner led several of his Brookline militia to the roadside, where they took cover behind a stack of casks and sniped at the British. But as the flank guards swarmed out, the Brookline men found themselves trapped, and the British mercilessly killed every one of them by ball or bayonet.117

Once the British cannon were primed and ready, the flankers took cover and the two 6-pounders thundered to life, belching forth white smoke and orange flame, sending their round shot directly into the throng ahead. The balls blasted toward the fresh militia, perhaps inflicting casualties as they smashed through, persuading the remaining Yankees to instantly disperse. The cannon’s roar was mightier than their bite, but in either case, they produced the desired result.118

The skirmish was short-lived, but Percy was the clear victor, having outsmarted Yankee ingenuity. Moreover, Percy averted a terrible disaster at the Great Bridge. Though he might not have realized it yet, his keen strategy had saved the British column. The Charlestown route also offered a shorter path back to Boston, shaving about five miles off their return march, or at a standard march rate, saving them almost two hours.119

The British drove through the hole made by their cannon and plowed eastward almost unmolested, for none of the Americans had been posted along that route. The militia horde still kept on the British heels, however, among them Colonel Heath and Dr. Warren. Thus, the rear guard was obliged to fire several volleys to keep the militia at bay, which in turn obliged Percy to relieve his rear guard marines with the 47th and later the 4th. Even so, the march to Charlestown was mostly uneventful.120

As the British approached Charlestown Common at the end of the mainland, which in turn led to Charlestown Neck, they saw about a mile to the north on Winter Hill the newly arrived militia from Salem, nearly three hundred strong. Their commander, Col. Timothy Pickering, had been reluctant to march to the fight until his men at last implored him. Now he came too late to give battle.121

On approaching Charlestown Neck, the thin strip of land that connected Charlestown Peninsula to the mainland, the advantage shifted. Here the militia could not encircle the moving column, which was fortunate for the British, for they had expended nearly all their ammo. By now, the sun had set and twilight was quickly waning. Still, a handful of shots whizzed out of those few houses that lined the final stretch to the Neck, the snipers barely visible in the dim light, illuminated primarily by the orange flame that glowed through the white smoke of their muskets as they fired.

One last innocent was killed here, in this, the most minor of skirmishes that day. A boy, just fourteen, curious and looking out a window as the column passed, lingered too long. The light was nearly gone, and a soldier, fearing the shadowy figure was a sniper, fired his musket and killed the boy, a tragic ending to the daylong battle.122

Once the British crossed the Neck, at about seven o’clock that night, they were at last safe. The bloodshed of April 19, 1775, was now over. Percy was modest when he gave his official reports, but the next day, when he wrote home to his father, he would confess, “I had the happiness…of saving them from inevitable destruction”.123

On Charlestown Peninsula, the triumphant brigadier general formed his men on the northwest side of Bunker Hill to cover the Neck, should the militia dare to cross. He also ordered the artillery to take up position there, but as they were almost out of shot, they must have sent to Boston for more rounds.

The militia, meanwhile, had no intention of crossing into Charlestown. Instead, they decided to take the defensive, just as the British had done. Colonel Heath, with Dr. Warren by his side, took command of the loosely organized multitude. He posted a large detachment on Prospect Hill to guard against the British leaving Charlestown. The rest he sent to Cambridge, from whence he sent another large guard across the Great Bridge to Roxbury, to take post outside Boston Neck.124

In Charlestown proper, the town’s selectmen sent a messenger to Lord Percy at Bunker Hill, offering that if he would agree to not attack the town, they would ensure the safety of the troops and would do all in their power to help them cross the Charles back to Boston. (In other words, the selectmen would do all in their power to get the British out of their town as quickly as possible.) Percy gladly accepted the selectmen’s offer. Within moments, the wounded troops and the weary light infantry and grenadiers headed down to Charlestown center. Once there, they found the town itself somewhat abandoned, for many had fled when they had heard the rumors of war to the west.125

Earlier that evening, Gage, perhaps in response to Percy’s messenger Lieutenant Rooke, had met with Admiral Graves at Province House, eager to discuss the matter of securing the British return. The admiral swiftly sent a courier to HMS Preston, his flagship, which hoisted a solid red flag to the main topmast head, then fired a cannon to signal the attention of the other ships’ captains. When the captains saw this predetermined signal flag, they immediately ordered all their remaining shipboard marines into longboats, which rowed up the harbor and down the Charles, coming alongside HMS Somerset just off Charlestown. The marines all boarded Somerset, ready to give aid to Percy’s reinforcement when they at last returned. The admiral would later claim credit for being the column’s savior, stating, “it was the Somerset alone that preserved the detachment from Ruin. The vicinity of that formidable Ship to Charles Town so intimidated its Inhabitants that they (tho’ reluctantly) suffered the Kings Troops to come in and pass over to Boston, who would otherwise have been undoubtedly attacked”.126

Even as his marines were redeploying to the Somerset, Admiral Graves urged his counterpart Gage to consider the prudence of the “burning of Charles town and Roxbury, and the seizing of the Heights of Roxbury and Bunkers Hill,” but “to this Proposal the General objecting the weakness of his Army” declined. The admiral then suggested that Gage bring up the 64th from Castle William, leaving that fortress to be manned by his sailors. Though Gage did indeed bring up much of the 64th, he still refused to take the offensive, his heart not yet turned to war. Graves proved very vocal when giving his opinion “that we ought to act hostiley from this time forward by burning & laying waste the whole country,” but as time would tell, Graves always urged aggressiveness when he did not bear responsibility for the outcome. If the decision were his alone to make, it is doubtful he would have shown the hostility he preached.127