“My whole life has been spent waiting for an epiphany, a manifestation of God’s presence, the kind of transcendent, magical experience that lets you see your place in the big picture. And that is what I had with my first compost heap. I love compost, and I believe that composting can save not the entire world, but a good portion of it.”

— Bette Midler in an interview with the LA Times

Composting is simple, but there are a few questions to ask yourself before you start.

• What kind of system is right for me?

• Where will I put it?

• What items can I compost?

• What items should I avoid?

• Where can I get compost ingredients?

This chapter will answer all these questions and more. The first thing you will need to explore are the different kinds of composting systems available so you can decide which type is best for your situation. Below is an overview of the types of compost systems available. Each type of system will be described in detail in later chapters, but this overview will give you the information you need to figure out what will work for you.

Types of Compost Systems

Compost heaps or piles

One type of system you can use is a simple compost pile or heap. This is probably most commonly known kind of compost system, and it is the easiest composting method if you have the space for it. A compost heap is a pile of compost material exposed to the elements, not contained in a bin. It is easy to add to it as you accumulate ingredients, so you do not have to collect a large amount of material before starting to build your pile. You can easily mix the ingredients because the pile is not contained. Use a pitchfork to toss items and combine them. This type of compost system can also take the form of a windrow, a long pile of material that is turned by hand (for small windrows) or by machine (for large farm-scale windrows).

Any open bin or pile may get some weed seeds blown into it and will also be more susceptible to rain, which will leach nutrients out of it. This leaching of nutrients is one main drawback of an open-heap system. Ideally, you want the heap to retain as many nutrients as possible until you are ready to use the compost in your garden. The contents may also blow and scatter around the yard if the pile is not covered. Covering an uncontained heap with a blanket or piece of carpeting is a good way to prevent the compost materials from blowing away and to keep the pile warm, aiding decomposition. If you cover the heap, make sure to use a breathable cover, not something like a plastic tarp that will trap moisture and cause mildew.

This method is best suited to rural areas because it does not have the neat and orderly look sometimes required in urban settings, and it can take up quite a bit of space. It may also be considered “unsightly” by neighbors, so you may have to situate it in an out-of-the-way spot or behind a fence.

Compost bins

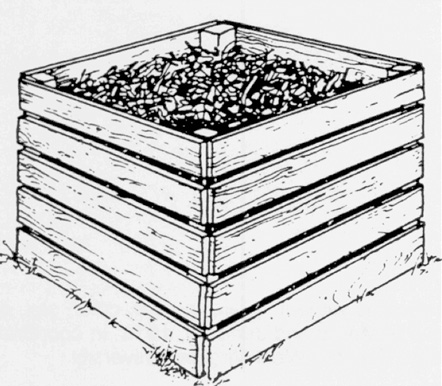

You can use a single bin or a series of three bins made of wood, concrete blocks, or hay or straw bales. These bins contain the compost ingredients, making for a tidier appearance more suitable in semi-rural or suburban neighborhoods. The materials used to build the bins can help keep the compost warm and can sometimes provide additional nutrients, as in the case of hay or straw bales, or wooden bins lined with cardboard. Bins must be stirred or turned with a pitchfork or shovel. Normally this type of system is large enough even for a very active gardener, but the bins can fill up, and you may have to store ingredients separately until the time is right to add them. Typically, the first bin in the common three-bin system is used to store materials as they are acquired. The second bin is used to combine the materials and begin the composting process and the third bin is used to finish off the composting process. Materials are forked from one bin to the next as time goes on, so you get a continuous supply of compost.

Example of a simple rustic compost bin.

Example of a simple compost bin. Courtesy of USDA.

Holes or trenches

You can use a hole or trench in the ground for composting. This method can work anywhere as long as you have dirt to dig in. The compost ingredients can be buried if you do not need the finished compost, or left in an open trench if you want to create compost to spread on a garden. Some forms of trench composting use plywood sides to contain the pile of compost above ground level, where it is then chopped and mixed using a rototiller. (A rototiller is a landscaping implement with engine-powered rotating blades used to lift and turn over soil.) This method is described in Chapter 3 under Wood Trench Composting. Composting in a hole can attract animals, so you will have to take some precautions to discourage them, such as covering the compost with dirt or covering the hole with a heavy lid. This composting method may be unsightly to neighbors and is not for everyone.

Cone digester systems

You can use a digester system where the compost itself ends up underground in a perforated bin while a plastic cone extends above ground level, allowing you to easily add material until it is full. You must move this kind of system periodically as the underground bin fills with solid waste. Liquid waste will soak into the surrounding soil and insects and small burrowing animals may make off with some, but probably not all, of the solid waste. This kind of system will only enrich the small area where the compost is buried. If the underground container is not rat-proof, you may end up with a rat problem because they can chew into the container to eat the scraps. This kind of system is not designed to make compost to spread on a garden. Like the hole system, the compost is left underground.

Rotating or tumbling barrels

You can either purchase or make a rotating or tumbling barrel to make compost. (Instructions for making a barrel composter are included in Chapter 3.) These systems are fully enclosed, so you do not need to worry about attracting animals. They also provide some protection from the elements and are easy to fill. Barrels are designed to allow air into the compost, and the tumbling action helps mix the ingredients. These systems come with a variety of different mechanisms for turning them. Some use a rotating handle with gears to assist in turning, and some are turned by pushing on them with your foot or by pushing and pulling them end-over-end by hand. Some models (especially the upright tumbling barrels that must be turned end-over-end) can be difficult to turn, and even more difficult to empty on your own, so you should take that into consideration if you will be the only one doing the work.

Stationary bins

You can use a stationary compost container. These are plastic bins, often provided by cities or towns, and come in a wide variety of shapes, colors, and designs. You must stir the ingredients manually to introduce air into the compost. These systems are very neat and are acceptable in most settings where you have some amount of yard space. Some types of stationary bins have no bottoms, which prevent liquids from building up and drowning the bacteria, but this also means that the ground around the bin may become saturated. Consider this when placing your bin. Outdoor vermicomposting bins, which use worms to digest the compost ingredients, are also of this type and can be used in some climates where the weather is temperate and not prone to extreme cold or heat because these conditions will kill the worms. (Vermicomposting is discussed in detail in Chapter 7.)

Example of a stationary bin.

Indoor systems

There are many types of systems meant for indoor use, including vermicomposting systems that use microbe-infused additives and systems that electrically heat and automatically tumble the compost ingredients. These can be used in homes, condominiums, and apartments and generally take up little space. The downside is that they may lead to odors or fly infestations if not properly maintained. They are very handy for people who have physical difficulties and cannot work with an outdoor compost system, and they drastically reduce the volume of kitchen waste sent to landfills.

How Big is a Compost Pile?

When most people think of an outdoor compost bin, they may envision anything from a giant pile of leaves, scraps, and random garden clippings to a small, tidy container with kitchen scraps and shredded paper. Compost that is contained in a bin or tumbler is only as large as the container the compost is housed in.

The size of a compost heap varies depending on the amount of space you have, the amount of ingredients you can assemble, and the amount of time and effort you want to invest in maintaining it. The typical size of an outdoor compost heap is approximately 4 feet by 4 feet and 5 to 6 feet high. This is large enough to get very warm, consume a large quantity of waste, and is manageable for most people to turn. When this book mentions “large compost piles,” you should envision this the size compost system. Smaller piles will also work, but they will not get as hot and cannot consume as much waste. Smaller piles are much easier to turn and may be preferred by some gardeners. Again, it is up to you to determine how much you can handle and how much compost you reasonably need to produce for your purposes.

Choosing a System

Now that you know the general kinds of compost systems available, you will have to make some decisions before you get started with composting. You can compost no matter where you live, but the kind of system you use and where you put it will depend on the kind of home and neighborhood you live in, available space, and how much you are willing to work or spend on your compost system.

The type of system you choose should fit your lifestyle and not be a burden. Composting is fun, and when you see garbage almost magically transformed into soil, you will wonder why you did not start sooner.

The following are some questions you should ask yourself to discover what kind of composting system will work for you:

• How much space do you have available?

• How much time do you have to tend to your compost?

• How much money do you want to spend to get started?

• Do you want to make a large amount of compost (enough for a garden), or only a little (enough for container plants)?

• How much yard and kitchen waste do you normally produce that can be used for compost?

• Do you want to do standard composting or vermicomposting?

• Do you want to do more than one kind of composting, for example, outdoor composting in the summer and indoor composting in the winter months?

Answering these questions will tell you what sort of system might be best for you. Chapters 3, 4, and 8 contain detailed information on creating and using various compost systems, and the table below may help you choose the kind of system that is right for you.

|

Compost bin (indoor) |

Vermicompost (indoor) |

Compost bin (outdoor) |

Compost heap or pile (outdoor) |

|

|

Rural |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Suburban |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

City |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Condo |

X |

X |

||

|

Apartment |

X |

X |

If you are in doubt about which kind of system you prefer, you may want to start with a smaller or easier system. While large three-bin outdoor systems are commonly seen in composting books and websites, they do take a lot of space and energy to maintain. A small in-kitchen composter or a stationary outdoor bin may be the best way for you to get started. Only you know your limitations and how much effort you will put into composting, so do not let yourself be overwhelmed by all the different choices.

Can I compost?

Almost anyone can compost. In addition to the kind of area you live in, the second biggest determining factor in what kind of system to choose is the amount of effort you are able to invest. Composting will occur even if you invest very little effort. You can pile up the compost materials, do nothing, and in a year or two, you will have compost. But if you want to make an effort and create compost in a few months, decide how much time you have for composting, how often you can tend to it, and how physically fit you are. If you spend time in your garden every day, you will have more than enough time for composting. If you work all day and only get into the garden on weekends, you can still compost using any method you like, provided you have the space. If you are physically disabled or live in a small apartment or condominium, your options are more limited, but you can compost using an indoor system.

The kind of system you use will depend mainly on cost, location, and effort, so take all those things into consideration when deciding which one is right for you.

What kind of system can I afford?

Compost systems come in a wide variety of types and price ranges from free ones your city or town may provide, to extensive homemade compost bins that can take up a lot of space and require a small initial monetary investment, to large commercially available systems with all the bells and whistles that cost several hundred dollars. You can compost with nothing more than a trash bag, or you can build several types of compost heaps, bins, trenches, and piles to compost different materials for different uses. Any method that keeps waste out of the landfill and provides you with quality compost is beneficial. The different methods of composting are listed briefly above and are discussed in more detail in Chapters 3, 4, and 8.

Where will the compost system go?

If you have a large rural property, options for where to locate the compost system are limited only by how far you want to walk to fill it, tend it, and empty it. You can locate your compost bin or pile anywhere on your property. For outdoor systems, you may want your compost either near your kitchen so you can easily fill the compost bin or container with kitchen scraps, or near your garden so you will not have to carry the finished compost too far. The ideal location is a level, dry, shaded area that is easy to water (within reach of a garden hose is good) and easy to transport compost to your garden. Place your compost pile on well-drained soil so it does not flood, which will stop the composting process. Never place a compost pile on a solid surface like concrete, pavement, or plastic; that will inhibit contact with natural microbes in the soil and may prevent proper drainage.

If you live in a city or urban area, you may have to balance your need for easy access with your neighbor’s desire not to look at a compost pile. You may be able to erect a fence around your pile to screen it from the neighbor’s view if necessary. You will also have to beware of runoff if you use an outdoor system. The liquid that drains from an active compost pile may contain ammonia or a surplus of nitrogen, depending on what is in your compost and how healthy the pile is. If this liquid runs into your neighbor’s yard, it may kill the grass or other plants. Your neighbors also may not want a mucky spot on their property courtesy of your compost’s runoff. To avoid this, you can grade the ground so that any runoff that occurs flows into your own yard. Grading is the process of leveling the ground so that it slopes smoothly in one direction or the other. You can do this with a shovel and rake or with a tractor with a blade, depending on how much soil you need to move.

You can also start the compost pile in a hole or depression in the soil, but then you also run the risk of the pile flooding. Flooding will not only wash away valuable nutrients, but also can drown the aerobic bacteria and cause the pile to become anaerobic, leaving you with a puddle of smelly muck. If you do decide to compost in a hole, realize that the compost will best be buried there, and you will not be able to dig it up easily to use in other areas. The best location for an outdoor compost pile is on well-drained, level ground, far enough from property lines that your neighbors will not have a problem with it.

Aerobic means air breathing. You want to encourage these bacteria and microorganisms to live in your compost because when they breathe, they release nothing more than carbon dioxide. Anaerobic means non-air breathing. These microorganisms release nasty-smelling gases, including ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, which makes anaerobic compost stink. Aerobic composting is generally preferred, although there are some situations where you might want to let things decompose in an air-tight environment, such as when killing weeds or making trash-bag compost, as described in Chapter 3.

If you live in a condominium with a tiny yard or in an apartment with no yard, balcony, or deck, you can still compost. There are small, enclosed systems available that take up little space. There are even indoor systems designed for use year-round that do not require any outdoor space. You can use the resulting compost in container gardens, donate it to community gardens, or sell it to other gardeners.

Are there local ordinances to account for?

There may be local restrictions on the presence and placement of compost bins or piles. These rules generally are put in place as the result of composting gone bad, such as when an inexperienced composter lets his or her pile go anaerobic, causing an awful smell. Well-meaning but misinformed people who assume that all compost stinks or is attractive to pests may also encourage anti-composting rules in their towns. While it is true that compost may attract vermin if it is in an open bin or not kept in proper balance, a properly maintained compost system, especially one that is enclosed in some kind of bin or container, will be no more attractive to pests than the average neighborhood garbage can, and probably less so, since it will not contain meat, fat, bones, or other items that scavengers will go after. While small creatures such as mice may still make their way into some types of bins, they will not stay if you keep it hot and turn it regularly. If pests do become a problem, check out the Troubleshooting guide in Chapter 9.

Some neighbors may complain because they do not want to look at your compost heap, and there may be local ordinances against having one in certain areas of your property, so it is a good idea to check with local authorities to see if there are any rules or guidelines about composting in your area. If you have municipal trash services, that will be the best place to inquire. If not, a call to your town or city hall should point you in the right direction.

Some cities pick up compost material from residents’ homes in much the same way that they pick up trash and recyclable materials. Some provide a central drop-off point where residents can bring their compost. Most cities that encourage recycling and composting will provide supplies, or at least information, to help you get started. They also generally make the community-created compost available for purchase to residents. This does several things. First, it keeps organic material out of the landfill. Second, it encourages people to think about what they are throwing away. Third, it provides inexpensive organic compost for the city and its residents, beautifying gardens and parks, and leading to a healthier environment overall. Depending on where you live, you may contact your local trash collection company, county extension agency, or town or city hall for information.

Some municipalities offer composting programs to residents, and in some cities composting is strongly encouraged. Cities such as San Francisco have started to collect compostable materials from residents and businesses to compost on a large scale. The city is able to compost items that a home composter cannot, such as greasy cardboard, meat, and bones. The finished compost is then sold to businesses, such as farms and vineyards. These programs vary across the country and around the world, so you will want to check the rules in your area. Some may charge a fee for the service while others, like San Francisco, levy fines if waste is not properly sorted.

Small kitchen recycling container.

If your city or town does not already collect kitchen and yard scraps for composting, you may think about championing the effort or starting your own composting group. Even if you just start small with friends and neighbors, you can help the environment and end up with nearly free compost. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.

Once you have chosen a compost system, the next question to consider is what items you can include in your compost system.

What Can I Compost?

You can turn almost everything that grows in your garden and many of the food scraps from your kitchen into compost. There are two major classes of composting materials: Green waste — items such as kitchen scraps, fresh grass clippings, cuttings from plants, green manure (plants like clover that are rich in nitrogen fixers), new-fallen leaves, and animal manure; and brown waste, which includes paper and cardboard, branches, twigs, tree bark, wood chips or sawdust, and dried grass or leaves. Later in this chapter, you will find an extensive list of ingredients that can be used in composting.

As with your own diet, the greater the variety of materials you put into your pile or bin, the greater the variety of nutrients you will have in the finished compost and the healthier it will be. Like any healthy diet, it is all about balance and variety. For example, a compost pile that has nothing but wood chips, which are very high in carbon, will take many years to break down. There has to be enough nitrogen-rich green waste to provide food for the microorganisms that eat the compost. Microorganisms are microscopic creatures, such as bacteria and fungi that break the scraps down into their component parts. The balance between the amount of green materials and the amount of brown materials is important. Chapter 2 discusses the chemistry of composting in greater detail, but for now, know that you need to include both green and brown waste to make your compost work at peak efficiency.

Yard and garden waste

If you have any kind of yard or garden, you have waste materials you can use in compost. You can compost leaves, spent plants or blossoms, and clippings from trees, shrubs, and hedges. You can also compost spoiled fruit and vegetables, along with the vines and plants they grow on. If you keep farm animals, their manure will make a great addition to your compost, as will old hay or straw, especially any that has been used for bedding. You can even compost the debris from your gutters during spring and fall yard clean up.

Green materials

You can collect green materials, also called wet materials, from your garden throughout the spring, summer, and fall. These items are high in nitrogen and decompose very quickly. When you mow the lawn, you can rake the clippings into your compost pile. Be cautious about adding too many fresh clippings to a small compost bin because they will quickly burn off available brown materials and turn the contents of the bin to muck. If you have only a small compost bin, it will be best to leave the clippings on the lawn to act as natural mulch. When you deadhead your flowers, toss the spent blossoms in the compost. Deadheading is the process of plucking dead blossoms from flowering plants to prolong the flowering period in perennials by preventing them from going to seed.

If worms, bugs, or other pests spoil the fruits and vegetables in your garden, toss the ruined items into the compost. If you are lucky enough to live on or near a horse, chicken, or cattle farm, you can ask the farmers for the animals’ manure. Many individuals are very happy to let you have all the manure you can shovel, but some larger farms charge for the privilege. They know the value of manure to a gardener. Other green materials you might use include wool, feathers from poultry, and hair from pets. These items are all high in nitrogen and will compost well.

Some weeds contain valuable minerals because their taproots can pull nutrients from deep under the soil where garden plants cannot reach. A taproot is a large root that grows straight down with smaller roots branching off it. Think of a carrot and you have the general idea of what a taproot is. These weeds are called dynamic accumulators because they gather up helpful nutrients from several inches under the soil. These nutrients are valuable in compost, and it is possible to safely compost non-pernicious weeds, as discussed later in this chapter. Pernicious weeds are fast growing and destructive to other plants. Weeds like thistle, bindweed, morning glory, and Bermuda grass are common examples of weeds that are generally considered pernicious.

Brown materials

You can collect brown materials, also called dry materials, throughout the growing season and even during winter. These items are high in carbon and decompose much more slowly than green materials. Every time you prune a bush or shrub, collect fallen branches or bark after a windstorm, or rake up dried leaves, you can contribute to the compost. A large concentration of brown or carbon-rich materials will take a very long time to break down, so these materials must be cut or chopped into small pieces. Dry hay or other dried grasses, as long as they are finely chopped, can also be put into the compost. Many people use a machete to chop long grasses and other fibrous plant material. A large kitchen knife or a small hatchet will also work. Chopping these elements will allow them to mix more thoroughly with the other ingredients and break down faster.

Non-living items such as wood ash, sand, lime, stone dust, finished compost, or garden soil may also be added to the compost although only very small amounts are needed.

• Wood ash (such as ashes left over from a campfire or fireplace) provides potash (also called potassium carbonate) and can be layered into compost every 18 inches or so. Use only a small sprinkling and mix it in well. Do not mix it directly with manure because the potash will leach nitrogen from the manure. Plants use potash to make chlorophyll, which allows them to transform sunlight into energy.

• Worms use grit in their gullet to grind up the plant material they eat, so a small amount of sand in compost will not hurt and might be beneficial. Grit is small, sharp granules of rock, and a gullet is part of the worm’s digestive system where food is pre-processed before continuing down into their intestines. Coarse or “sharp” sand helps increase aeration in compost by providing larger pores in the finished compost for air and water to flow through. This can be useful when adding compost to clay soils. Sand does not provide any nutrients.

Worms use grit in their gullet to grind up the plant material they eat.

• Some people add lime to their compost to counteract acidity if they have a lot of acidic materials such as pine needles and coffee grounds in their compost. It can also be added to worm bins or compost heaps if they get wet and smelly or too acidic. If using limestone in a worm bin, make sure to add only a very small amount and to stir it in well over several days, because it can react with the compost and release carbon dioxide, which will suffocate the worms. Lime will also leach nitrogen from a compost pile and can cause the release of ammonia and nitrogen gas if it is sprinkled directly onto fresh manure, so it should be used sparingly, if at all. See the following for more information before deciding whether or not to add limestone to your compost.

SHOULD YOU ADD LIME TO YOUR COMPOST?

Lime used in agriculture is a fine, white powder made from ground up limestone. It is made up mostly of calcium carbonate and is used to decrease acidity in soil. There are other kinds of lime, such as pickling lime and slaked lime, but these have a different chemical makeup and should not be used in composting.

Because lime can cause problems in a compost heap (it can leach nitrogen and release carbon dioxide), it is best to wait until a few weeks after you have enriched your soil with finished compost and then test the soil’s pH level. If the soil is still too acidic, add lime directly to the soil to bring it closer to neutral. Lime can be purchased at any garden supply store and most hardware stores with a gardening section, and the package will contain information about how much to use. Your pH testing kit should also tell you if you need to add any lime and, if so, how much to apply.

Using lime is discussed more thoroughly in Chapter 6.

• Finished compost or garden soil will introduce beneficial bacteria and both are good for getting a new compost pile or bin started.

• Stone dust, which you can obtain from a quarry or landscape supply store, will add minerals, including calcium and magnesium, that might not otherwise be present that can correct over-acidity in worm bins and kitchen waste systems. A light sprinkling is usually enough to add these valuable minerals to the pile.

WHY ADD STONE DUST TO COMPOST?

At first glance, it may seem odd to add stone dust to compost. After all, the ground contains plenty of stones already. But plants cannot get any nutrients from the rocks their roots encounter. The minerals contained in the rocks are locked together tightly. In order for plants to absorb them, the minerals must be in minute granules that the roots can take up.

Volcanic eruptions regularly bring minerals up from deep in the earth’s crust. As volcanic ash breaks down, it releases minerals into the soil that might not be there otherwise. These minerals are an important component in the fertility of soil all over the world. By using stone dust in your compost or limestone on your soil, you are replicating the role of volcanoes by distributing rock dust in tiny granules that plants can use.

Kitchen and household waste

A surprising amount of food waste thrown in the trash every day can be composted. Take breakfast leftovers, for example: coffee grounds and tea leaves, the rind and peels from fruit, and egg shells can all be added to the compost pile. Coffee and tea are high in nitrogen, and eggshells are mostly calcium, a mineral plants use to build cell walls. The fruit peels provide a high concentration of carbon, which is essential to plants and a valuable component of compost.

If you plan to compost, one thing you will get used to doing is saving nearly all of your organic kitchen waste. You can use nearly any sort of container for kitchen waste. Garden supply companies (both online and brick-and-mortar stores) sell a wide variety of fancy containers that can match your home décor, but if you are composting to save money and do good for the environment, it does not make sense to buy an item that has to be specially manufactured for a single purpose and then shipped hundreds, or thousands, of miles to get to you. Instead, reuse items such as coffee cans with lids, plastic ice cream or yogurt containers, or a baked bean crock. If you are not familiar with a bean crock, they are large jars made of crockery with tight-fitting lids. This will keep fruit flies out of your scraps and will keep any smells in the crock. If your family eats a lot of fresh fruit and vegetables and produces a lot of waste on a regular basis, you may even want something larger, such as a plastic cat litter bucket or a plastic trash can with a lid.

You can mix household browns, such as torn or shredded paper or the dead leaves from houseplants, with food scraps to help absorb some of the liquid and keep the bin from getting too anaerobic and smelly. You should empty the bin every couple of days, or as it fills, to avoid attracting fruit flies or ants. Always wash the bin with dish detergent and hot water after emptying it. If the container has become infested with mold, as it can during hot weather, you may want to wash it with detergent, and then wash it again with a bit of household bleach in water. Rinse and dry it thoroughly before using it again. You may also want to use biodegradable bags to line the container if you are squeamish about handling the waste.

Food items to compost

You can compost almost any plant-based food item, including fruit and vegetable waste (peels, stems, pulp, and rotted bits); tea leaves and coffee grounds; flour or rice that has gone rancid; and nuts, seeds, and grains. Although these items may no longer be fit for human consumption, the microbes in a compost pile will still break them down into their component parts with no trouble. Any food made mostly from plant matter and raw ingredients that may have spoiled or gone past their prime can be used in composting. Spring cleaning provides an opportunity to clean out the kitchen cupboards and the freezer. Freezer-burned fruit or vegetables can be composted, as can expired yeast, condiments, moldy bread, and stale herbs and spices. While these rancid or freezer-burned foods will not be appetizing to humans, microorganisms will not care that they smell a little bit “off” and will happily consume them.

Large fruit or vegetable seeds, such as peach or avocado pits, will decay, but it may take as long as several months or even years to break down large seeds so you may want to avoid adding them to your compost. Some vegetable seeds may also sprout in the compost pile. If this happens, you can either let them grow or dig them back into the compost to rot. There is a difference of opinion about whether you should eat crops grown in unfinished compost. Some say that to do so can cause stomach upset, while others grow vegetables in their compost on purpose to take advantage of the nutrients. If you want to beautify your compost pile, you can always allow flowers to grow on it so you get the beauty without the potential of risk to your health.

Eggshells, seashells, and the shells from crustaceans like shrimp and crabs are excellent sources of hard minerals, although they take longer to break down. You should rinse and crush items such as eggshells, seashells, and nutshells so they will break down faster. To crush seashells or crab and lobster shells, rinse and dry them, then put them in a heavy-duty paper bag. Smash the shells with a hammer then pour the contents of the bag into the compost. If you will not be reusing the bag again soon, you can rip it into pieces and compost it. If you are composting salted peanut shells, be sure to thoroughly rinse the salt off them as salt can be bad for a compost pile. Chop up large items, such as whole banana peels, citrus skins, and spoiled fruit and vegetables. Whole citrus peels will decompose more slowly than other fruit peels because they contain antimicrobial oils that can kill off microorganisms in the compost. Cutting them into smaller pieces will help them to break down faster. Too many citrus fruits (such as ones you might get from the local juice shop) might make your compost very acidic. As long as you balance the other ingredients, this should not be a problem, but you will want to test your soil several weeks after using acidic compost on it, just to be sure the pH is in a good range. If you are vermicomposting, go easy on citrus, because it can be harmful to worms. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

Non-food items to compost

Many items that are routinely thrown out or recycled can be composted at home. This includes newspaper, paper bags, paper towels used to wipe up food spills, shredded office paper, non-metallic wrapping paper, cardboard, natural fiber cloth, yarn, or string. Although it is generally better for the environment to recycle these items, you can compost them if you live in an area where you do not have recycling facilities or do not have many deciduous (leaf-bearing) trees, and do not have enough brown materials, such as dead leaves or fallen branches. Shredded paper or cardboard makes good bedding for vermicompost bins, and it absorbs excess fluid in enclosed compost bins and tumblers. You should not try to compost cardboard that is coated in plastic because it will not break down properly, and you may be introducing unwanted chemicals into the compost.

You can dump spent potting soil into the compost after transplanting houseplants to provide some grit for worms and other creatures in the pile and to re-enrich the spent soil. You can also empty the contents of vacuum cleaner bags or canisters into it, as long as you do not have synthetic carpeting. Because synthetic fibers will not break down in compost, it is better not to use vacuum dust if you are not sure what kind of carpeting you have. You can also compost floor sweepings and nail clippings.

Most colored ink is made of vegetable-based dyes now, which makes the inked papers safe to compost. This includes colored newsprint, wrapping paper, and anything with colored ink from a computer printer. Paper takes a very long time to break down, so shred, and dampen the paper before adding it to your compost. Used coffee filters compost well because they are already damp and covered in nitrogen-rich coffee grounds. Glossy paper, like the kind found in magazines and catalogs, will compost eventually, but it can take a long time due to the shiny coating. Because all paper is made of cellulose, it will use up a large amount of nitrogen to break down. The cellulose found in paper and plants provides energy and a source of carbon for the microorganisms in the compost, but it is a good idea to layer paper with fresh grass clippings, coffee grounds, or some other high-nitrogen item to ensure proper and complete composting.

Seaweed is another item you might have on hand if you live anywhere near the ocean. Seaweed contains iodine and boron, which are essential nutrients. Boron helps plants to build cell and seed walls. According to organic lawn care company Ecochem (www.ecochem.com), boron is essential for preventing a wide variety of plant disorders, including stunted appearance (rosetting), hollow stems and fruit (hollow heart), and brittle, discolored leaves. Iodine is essential in the human diet, so ensuring that your vegetables have a source of iodine helps make certain that you consume enough iodine to avoid common diseases, such as a goiter, an enlargement of the thyroid gland.

If you collect seaweed from the ocean, do so immediately after a storm or high tide. Do not pick live seaweed as in many areas harvesting seaweed is against the law. Do not pick seaweed that has been sitting on the beach for a long time because it may have a high salt content and will ruin the soil. If the seaweed is dry and crunchy, chances are it has been there too long. If you pick up seaweed from the beach, choose seaweed that is not rooted in the sand and is still wet and pliable. You can also compost sea grass, but in some areas, it is against the law to collect it. You should call the Department of Natural Resources in your area to make sure it is legal to harvest sea grass if you decide to compost it.

Shells such as egg, crab, shrimp, lobster, clam, mussel, and oyster shells can all be composted. They contain calcium carbonate, which neutralizes acidic soil. Calcium carbonate also prevents a disease called blossom end rot that is caused by calcium deficiency in the soil. This disease causes black spots to appear on the blossom end of fruits such as tomatoes. If you are adding shells from a crustacean to the pile, rinse them well, smash them into small pieces with a hammer, and bury them in the middle of the pile where they will be safe from scavengers. If that is not possible, put them into a digester, tumbler, or other enclosed system to prevent pests from digging them out of the compost. (Digesters are underground compost systems described in detail in Chapter 3.)

Natural fibers such as cotton, silk, bamboo, hemp, and wool can be shredded or cut up and added to compost. This is a great way to use up leftover bits of cotton quilting fabric or natural fiber yarns. Because these are all made from natural substances, they will break down easily in the compost. Avoid any cloth that contains any artificial fibers such as polyester, Spandex, or rayon.

If you are doing home renovation and have unpainted scraps of gypsum board or plasterboard, you can smash them up into small pieces and compost them. This product is made from ground gypsum, which is a common mineral, and coated with paper. Modern gypsum board uses recycled paper and low volatile organic compound (VOC) adhesives, so it should not harm your compost if it is used in small amounts. The paper will compost readily, and the gypsum will add minerals to your compost.

Other sources of compost material

If you want to create a large compost heap (the different sizes of compost heaps are discussed in Chapter 2), but do not have enough material on hand, you may be able to collect it from local businesses that have an excess of leftover organic materials. Here are some suggestions for businesses to approach about collecting compostable materials and the materials you will be able to compost from these businesses.

• Brewery — hops waste (green/nitrogen materials)

• Cider mill — apple waste (green/nitrogen materials)

• Coffee shop — coffee grounds (green/nitrogen materials)

• Farm — manure (green/nitrogen materials) and old hay or straw bales (brown/carbon materials)

• Juice bar — fruit and vegetable pulp and peels (green/nitrogen materials)

• Landscaper — dead leaves, hedge trimmings (brown/carbon materials), and grass clippings (green/nitrogen materials)

• Poultry farm — manure (green/nitrogen materials)

• Quarry — stone dust (marble or granite) (non-organic materials)

• Winery — grape and other fruit waste (green/nitrogen materials)

• Wood shop — untreated sawdust or chips (brown/carbon materials)

Materials to Avoid Composting

Some items just will not compost, and other items contain seeds or chemicals that can invade the garden or damage the soil. You should never introduce anything into your compost that you do not want to spread on your garden. While almost all organic materials can be composted, you should avoid some.

Organic materials

One organic material you should avoid is diseased plants. Diseased plants might break down in the compost, but the composting process may not destroy the pathogen that killed the plant, and it can spread to your other plants. The nutrients you might get out of the diseased plants are not worth the risk of infecting next year’s crops, so it is best to dispose of sick plants by whatever method is customary in your area — either by burning them or by disposing of them as directed by your municipal waste authority.

IDENTIFYING DISEASED PLANTS

If a garden plant dies unexpectedly, check to make sure there are no obvious signs of disease before tossing it into the compost pile. Signs of rot, mold, or mildew can indicate any number of plant diseases, and it is probably best not to compost that plant. If a plant dies due to insect infestation, thirst, or some other non-contagious cause, it is perfectly fine to put the plant in the compost. Make sure you rinse away any potentially harmful insects before you add the plant to the compost pile to prevent the possibility of them surviving the composting process and re-infesting your garden.

Plants may have a mineral deficiency rather than a disease. The points below will help you tell if a plant is lacking in nutrients.

• If lower leaves are pale green or yellow or if growth is stunted, the plant may lack magnesium.

• If leaves are red or purple and should not be, the plant may be lacking phosphorus. Plants with this deficiency may also have pale upper leaves and refuse to flower or set fruit.

• If a plant does not seem vigorous and produces small fruit with thin skins, it may be lacking in potassium.

• If lettuce leaves look burnt on the ends, or tomatoes and peppers develop blossom-end rot, the plant lacks calcium.

• If leaves are speckled or curly, if the stem is weak, or the roots are not developing properly, the plant lacks nitrogen or potassium.

• If new leaves are yellowish instead of green, the plant lacks sulphur.

Despite their mineral deficiencies, these plants can be added to the compost if they are disease-free. They will be broken down like any other plant, and the nutrients that they do possess will be passed along to other plants through the process of composting.

Pernicious weeds, especially non-native ones, are extremely hardy, and some of their seeds might survive even in a very hot compost pile. A pernicious weed is any weed that is invasive and destructive to other plants or to the habitat it grows in. Often they are non-native species, so the kind of weeds considered pernicious in one area may be tolerated in other states or countries. Some types of pernicious weeds that should not be composted include morning glory, bindweed, sheep sorrel, ivy, several kinds of grasses, and other plants that can regrow from their roots or stems in your compost pile.

To avoid spreading invasive, non-native species, you should burn these plants, if allowed in your area. Other methods of disposal include drowning them for six weeks by weighing them down in a bucket of water, or asphyxiating them by sealing them in a black plastic bag for one year before disposing of them. Otherwise, ask the local waste management authority how to dispose of them. Putting them into a landfill will just allow them to continue spreading, so this may not be the best option.

PUTTING PERNICIOUS WEEDS TO GOOD USE

One good use of pernicious weeds is to make weed tea. Many weeds concentrate minerals and soil nutrients in their taproots, and it is a shame to let those nutrients go to waste. You can make weed tea in much the same way you make compost tea.

1. Secure the weeds in a cloth bag and tie the top tightly so bits of roots or leaves cannot escape.

2. Submerge the bag in a bucket of water and let it soak for at least four to six weeks.

3. After four to six weeks, check the bucket and make sure there is brown sludge in it and that the weeds are dead. This sludge will smell very bad, so you may want to do this in an out-of-the-way place. You can compost the drowned weeds.

4. Dilute the sludge to make a weed tea, one part sludge to ten parts water, and use it to water plants.

Fresh manure, especially chicken manure, is extremely high in nitrogen and can burn plants, causing the leaves and stem to turn brown and wither if it is applied directly to the garden. It is often mixed with urine, which contains urea and exacerbates the problem. Fresh manure contains digestive bacteria that are not helpful to plants and can upset the balance of the compost pile by killing some bacteria. It is best to use aged manure that has been left in the elements for at least six weeks. Horses digest only about one quarter of the grass and grains they eat, which produces weedy manure that may be undesirable for composting. However, cows have four stomachs so their manure is more digested and has fewer weed seeds in it, making it a better choice for composting. If you cannot obtain manure directly from a farm, you can use bagged manure sold in garden supply stores, but this may be an expensive option. Bagged manure can be used to start a brand new compost pile if you do not already have mature compost to use.

The table shows approximate carbon to nitrogen ratios in the manure of several common animals. Those with higher amounts of carbon will not need as much brown material added along with them. Whatever you have available to you will be helpful to your compost. Just remember to add an appropriate amount of carbon-rich material to offset the high nitrogen content of some manures, especially chicken manure.

|

CARBON TO NITROGEN RATIO IN COMMON ANIMAL MANURES |

|

|

Alpaca, llama, horse, donkey |

15:1 to 25:1 |

|

Chicken, turkey, rabbit |

4:1 (without bedding) 10:1 (with bedding) |

|

Cow, goat, pig, sheep |

10:1 to 15:1 |

You should never use human or pet waste in a conventional compost pile because of the risk of disease, especially worm-borne illnesses. Humans are susceptible to many of the same parasites as dogs and cats, such as hookworms, roundworms, tapeworms, and heartworms. For this reason, handling pet waste is not a good idea. Pregnant women, in particular, as well as people with suppressed immune systems, should not handle cat waste because of the risk of toxoplasmosis, which can cause deafness, blindness, or learning disorders in infants who are infected before birth. Although some high-heat compost systems can destroy pathogens and some advanced gardeners use “humanure,” it is best not to take the risk of handling human or pet waste. Horse and cattle manure is different than human or household pet waste because these animals are normally strictly vegetarians and are less likely to pass along diseases. If you do compost dog feces using a commercially produced, pet waste septic system, the resulting compost should never be used on vegetables, herbs, or fruit trees, although it can be used on non-fruit-bearing trees, shrubs, and flowers. A septic system of this kind should be kept away from streams due to the high phosphorous and nitrogen content.

Another organic material you should avoid is coal ash, such as that left over in a charcoal grill. Although charcoal is made from wood, coal ash will introduce sulfur into the compost, and thus into your garden, and will poison the soil. It is best not to use it. You should not put cooked food into compost heaps because it will attract flies and other pests. It can be disposed of in worm bins and digesters. Indoor composting systems can usually handle cooked food, but be sure to follow the guidelines that come with the product. (Worm bins, which are used in vermicomposting, will be discussed in Chapter 7.)

Items made of real rubber, which is organic, will eventually break down, but it may take several years so rubber should also be avoided. Meat, grease, dairy products, and other animal products, including used cat litter, should not be used in most types of household compost systems. There are three reasons to exclude animal products from your compost.

1. It will smell. Decomposing meat will stink unless enclosed in a high-heat compost system designed to break it down.

2. It may attract vermin. Rats, raccoons, possums, dogs, and other creatures may come to your compost pile looking for food. These scavengers generally will not be attracted to decomposing plant material, but decomposing meat is what they live on, and if it is in your compost pile, they will be too.

3. It will slow production of your compost. Fats found in animal products can coat the vegetable matter and prevent oxygen from reaching the composting material. This will drastically slow the process because the microbes in your compost system need to breathe. If fats and grease smother them, they will die and anaerobic microbes will take over, which will cause an unpleasant odor. The only exception to this is the EM™ Bokashi fermenting compost system (described in detail in Chapter 8), which is designed for anaerobic composting, digester systems, electric composting systems, or worm bins.

Keeping diseased and other compost-unfriendly items out of the compost bin will lead to a healthier garden and a more pleasant composting experience.

Non-organic materials

A compost heap is not a garbage dump. Even though this book started off saying, “garbage becomes a rose,” that did not refer to literal garbage. Very few non-organic materials are safe or necessary in a compost heap. You should not try to compost non-organic items, such as glass, metal, cans, bottles, and plastic-coated containers. These should be recycled instead. Plastic-coated containers will not break down properly, and they may introduce undesirable chemicals into your compost, which will then be passed on to your fruit and vegetables. Often, while sifting compost you will find small plastic labels like those found on produce. They will look as shiny and new as they did the day you put them in there because the microbes cannot break down the plastic. Pick them (and any other non-organic items) out of the compost as you sift it.

Items that contain any kind of human waste are not safe for most home composting systems because these systems usually do not get hot enough to kill off the pathogens (viruses and bacteria). These can cause illness when the finished compost is handled. Do not put disposable diapers into compost. Even the ones that are sold as compostable contain human waste, and you should avoid using them in household composting. However, they are safe for use in large municipal composting systems because those systems can compost thousands of pounds of waste at a time, producing extremely hot compost that can kill off nearly all pathogens. Used facial tissues can be composted in hot heaps or totally enclosed systems, but should not be put into the stationary Dalek-type composters because the human pathogens they contain will not break down at cooler temperatures. (Dalek-style composters are stationary plastic compost bins for outdoor use and will be described in detail in Chapter 3.)

Activators

Activators are substances that can help the composting process begin, but they are not necessary in most cases. There are many products on the market that claim to help start the composting cycle by introducing beneficial bacteria, enzymes, and hormones. However, because the food and yard waste that is deposited into the compost is already covered in bacteria and because bacteria create their own enzymes to take advantage of their environment, you will not need store-bought activators, or inoculants.

Many activators are designed to introduce more nitrogen into the compost, but adding more fresh green materials will increase the nitrogen enough to start the reaction. The Texas AgriLife Extension Service, which provides information and how-to education on all aspects of agriculture, conducted experiments where compost piles were prepared using a variety of starters, including horse manure, compost, soil, and commercially available activators. Another set of compost piles was prepared using no activators at all. The organization found that there was no major difference between the two groups of compost piles. It concluded that composting would work just as quickly without activators as it will with them; therefore, there is no real benefit to adding bacterial or nitrogen activators to a compost pile. The best way to keep your compost perking away is to keep the correct balance of green and brown items and to aerate it as necessary to allow the microorganisms to do their job.

Some composters like to use activators to get compost going quickly or if they are lacking certain compost ingredients. They are also useful if you do not have finished compost to put into a new pile, although in that case you can just buy a bag of compost and use that to get things started. Composters who live in very cold climates sometimes use activators to make up for the lack of warm temperatures that make bacteria thrive. Most activators contain nitrogen, bacteria, fungi, or some combination. There are both natural and artificial activators, and both types can be found at most gardening supply stores that have a compost section, or online at places such as Amazon (www.Amazon.com) or Gardener’s Supply Company (www.gardeners.com). A quick Internet search will turn up hundreds of places to buy activators, but buying locally may be the best bet if you are not sure exactly what you need, so you can ask a salesperson any questions you may have.

Natural activators

If you are creating compost for organic, chemical-free gardening, you will most likely want to stick to the natural activators, which include compost, soil, manure, and meals of alfalfa, blood, bone, fish, hoof, and horn. Meals are created by drying and grinding up organic materials. They can be animal or vegetable in origin. Keep in mind that activators, even the natural ones, and the fruits and vegetables you put in your compost may contain traces of antibiotics, growth hormones, pesticides, and other chemicals.

Alfalfa meal

Alfalfa meal is dried and ground up alfalfa, which is a type of grass high in nitrogen. To use this in your compost, spread a layer every 6 inches in the compost and water well. Alfalfa meal is very useful for heating up a compost pile when you do not have enough green materials to feed it. It contains a small amount of three important nutrients: nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium. You can purchase a 50-pound bag for about $40.

WHAT IS NPK?

NPK is shorthand for nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium found in various kinds of fertilizers and soil enhancement products. The initials come from the chemical symbols for each of the nutrients. Nitrogen is N, phosphorous is P, and potassium is K. Each of these nutrients is vital to the health of plants, and you need to be sure that each plant is getting the right amount of each nutrient for that particular plant type.

Fertilizers are labeled with a series of three numbers that indicate the relative amount of nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium in the given fertilizer. For example, a 5-10-5 fertilizer contains five parts nitrogen, ten parts phosphorous, and five parts potassium.

Blood meal

Blood meal is dried animal blood. It is high in nitrogen and slowly releases it, along with trace minerals, into the compost. (Trace minerals are nutrients, such as copper, zinc, and iodine, which are required in the diet in very small or “trace” amounts.) Blood meal is expensive, more than $1 per pound, and is better used directly on the soil around garden plants than directly in the compost. It nourishes the plants and frightens plant-eating animals away. Blood meal is an ingredient in many animal-repelling products. To use blood meal in compost, spread a layer every 6 inches in the compost and water well. To use it on garden plants, mix it with water in the proportions directed on the package.

Bone meal

Bone meal is made of dried, crushed bones. To make your own bone meal, cook bones left over from roasted meats as if you are making stock. Allow the bones to dry out in a low-temperature oven, or put them in the oven after you have used the oven for baking to take advantage of the residual heat. As the bones dry out, crush them in a large mortar and pestle. (A mortar is a sturdy container, usually made of stone or wood, in which hard items are ground or pounded into a powder using a pestle, a club-shaped stick, usually also made of stone or wood.) Sprinkle the meal onto the compost heap or in the worm bin. Spread a layer every 6 inches in the compost and water well. Bone meal contains a variety of minerals, including calcium, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, and zinc; it makes an excellent bulb fertilizer and can be purchased for just over $1 per pound.

IS IT SAFE TO USE CATTLE-BASED MEALS?

After the mad-cow disease (Bovine spongiform encephalopathy) scare in the 1990s, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) made changes in how commercially raised cattle are fed in the United States. According to the FDA, these changes, made in 1997, forbid the use of mammal protein, such as beef or mutton in the feed given to ruminants. Therefore, it is considered safe to use products such as blood meal, bone meal, and hoof and horn meal manufactured since that time.

Even though cattle-based meals have been declared safe, blood, hoof, bone, and horn meal are all by-products of cattle processing, and some people choose not to use them. For the same reason, some people choose not to use feather meal, which is a by-product of chicken processing. There are a variety of non-animal-based meals to choose from that will do the job just as well.

Compost

Using compost from a previous batch is a good way to introduce beneficial bacteria and enzymes to a new compost pile. Spread a 2-inch layer of finished compost every 12 inches when layering materials.

Cottonseed meal

Cottonseed meal is made of dried and ground-up cotton seeds. Cotton is a heavily sprayed crop and the cottonseed meal may contain pesticides, so it is best to avoid it if you are trying to make organic compost or if you intend to use the compost on food plants. To use cottonseed meal, spread a layer every 6 inches in the compost and water well. Cottonseed meal is high in nitrogen and also contains phosphorus, potash, and other minor elements. Cottonseed meal can acidify the soil. According to organic garden supply company Extremely Green (www.extremelygreen.com), it takes 9 pounds of limestone to neutralize the acidity of 100 pounds of cottonseed meal, so consider this when using it. Cottonseed meal costs about $1 per pound.

Feather meal

Feather meal is made from cooked, dried, pulverized chicken feathers. It has an NPK content of 13-0-0, so has the same nitrogen content as blood meal. It degrades over the course of two or three months, more slowly than blood meal. It is good for mixing with mature compost as a fertilizer. Feather meal will not heat up a compost pile. It costs just over $1 per pound.

Fish meal

Fish meal is dried and ground-up fish or fish parts. The oil and water is pressed out of the fish, and the remaining product is dried. Spread a layer every 6 inches in the compost and water well. Fish meal is high in nitrogen, amino acids, and vitamins. It has an NPK content of 10-6-2 and releases these nutrients quickly at temperatures above 60 degrees. The strong odor may attract animals, so keep that in mind when using fish meal on your compost. It costs just under $1 per pound.

Hoof meal and horn meal

Hoof meal is made from the ground-up hooves of ruminant animals, while horn meal is made from their horns. The raw material is obtained from slaughterhouses and cattle processors. Both are high in nitrogen and have some phosphorus. The nutrients leach more slowly from hoof and horn meal than they do from blood meal, giving plants a more constant source of nutrition. Spread a layer every 6 inches in the compost and water well.

Manure

You can use dry, aged manure from poultry, including chickens, geese, ducks, turkeys, and pigeons. You can also use horse, cow, sheep, goat, llama, or pig manure, and manure from small animals like rabbits. Aged manure is best for composting, as fresh manure is often wet and introduces too much moisture to the compost. Manure contains nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and minor nutrients such as calcium, magnesium, and sulfur.

Soil

Garden soil from a healthy patch of ground is rich in microorganisms and macro organisms. Avoid using soil from areas that have been sprayed with herbicides or pesticides because they linger in the soil. Use about 2 inches of soil for every 6 inches of other materials.

Urine

Urine contains urea, which is high in nitrogen. If you are using manure in your compost, chances are it already contains urine. Some composters dilute their own urine (four parts urine to one part water) and pour it on the compost pile instead of plain water. Urine is also a bacterial activator and is useful if you do not have mature compost to add to the bin.

Bacterial activators are useful in very hot, dry, or cold environments where bacteria grow slowly. They cannot hurt the compost, but studies show that they will not help it much either. Whether you use them or not is up to you. Some composters report better outcomes when using activators, although studies by the Texas Agrilife Extension Service (see below) have shown that they make no difference to the outcome.

All these activators are high in either nitrogen or bacteria. Vegetarians and vegans may want to avoid using blood, bone, fish, hoof or horn meal, and possibly manure, but alfalfa and cottonseed meal, compost, and soil are all non-animal sources of natural activators.

DOG FOOD IN MY COMPOST?

Dog food, as well as rabbit, chicken, or goat feed, can act as natural nutritional activators in compost by providing a large hit of nitrogen. For example, 15 pounds of rabbit or goat feed will heat a cubic yard of compost to about 140 degrees. Check the label to make sure it is a 100 percent vegetable formula.

Animal feeds typically heat the pile quickly and are consumed quickly, so it is helpful to add another, longer-lasting source of nitrogen to the pile when you add the feed. You can use manure or fresh grass clippings in conjunction with the feed to maintain heat in the pile beyond the initial burst of energy.

To heat up the average-sized home compost heap, which is about 12 cubic feet, or slightly less than a cubic yard, add about 20 percent grass clippings or manure (1 part grass or manure to 4 parts compost) and one of the following:

• 8 pounds of cottonseed meal

• 20 pounds of dog food, or rabbit or poultry feed

• 10 pounds of soybean meal or canola meal

• 8 pounds of organic fertilizer

A pile heated this way should be turned every two days and watered as needed until it cools.

Artificial activators

The most common artificial compost activators are chemical fertilizers. These products give compost a big surge of heat by adding nitrogen, and if there is not enough carbon-rich material to counteract it, your compost can burn too hot and turn anaerobic once all the carbon has been used up. Make sure to keep the balance of green and brown in mind when using artificial activators.

Chemical fertilizer

You can use a 10-5-10 fertilizer, which provides 10 percent nitrogen, 5 percent phosphorus, and 10 percent potassium, to spike a compost pile. Every fertilizer should list what ratio of nutrients it provides on the package. This will help you choose the right fertilizer for your needs. If you choose to use fertilizer, you should use 1 cup of fertilizer for every 10 square feet of level compost pile surface and repeat this every 6 inches. However, chemical fertilizers do not have protein mixed with their nitrogen the way natural activators do and are not as helpful to compost.

Ammonium sulfate is a type of manufactured fertilizer that combines nitrogen and sulfur. It can be diluted with water and is sprayed on croplands. While adding this product to your compost bin or pile will introduce a large amount of nitrogen, it will defeat one of the main purposes of making compost in the first place: to have a free form of fertilizer that is completely organic or at least mostly free of chemicals. If you are going to buy ammonium sulfate to feed your soil, you will be better off spraying it directly onto your garden rather than putting it in your compost. Be aware that the state of California requires a warning on this product because it is known to cause cancer, birth defects, or other reproductive harm. While it is used on many commercial crops, you should carefully consider adding this chemical to your vegetables or herbs. This product has also been shown to acidify the soil and harm some species of earthworms.

Ammonium nitrate is another common fertilizer that is sometimes recommended for composting. It will not heat a compost heap very much, and it may kill the microorganisms in the compost. Be aware that in the United States there are both federal and state laws concerning how much ammonium nitrate a person can buy at one time because people have used this product to make bombs. Other countries may have similar laws.

Preparing Waste for Composting

Collecting your kitchen and yard waste is only part of the process. Whole fruits and vegetables, entire branches, and bundles of paper will not compost very well if left in that state. The smaller the materials are, the easier it will be for the organisms in the compost to consume them. On the other hand, you do not want to reduce materials to a powder because they can compact and reduce airflow, therefore slowing decomposition. Heavy vines, like those from pumpkins or tomatoes, should be chopped up, and items like branches and corncobs can be crushed with a hammer. You should pierce the skins of whole fruits and vegetables or chop up large pieces of fruit so that bacteria can get inside more quickly.

You should process branches and sticks with a wood chipper; shred leaves; chop food waste into small pieces; and crush items like egg or seashells. To speed the process of composting, you should tear up paper and cardboard and soak it in water for a few minutes before adding it to the compost bin or pile. To compost cardboard boxes, remove all tape, stickers, and staples and soak the cardboard in water for at least ten minutes. The water will leach out water-soluble glue and other chemicals. Pour this water in a place where edible plants cannot absorb it. The small amount of glue residue left on the cardboard will not harm the compost because the fungi and microorganisms will decompose it.

Composting weeds

As mentioned earlier, some weeds contain a wealth of nutrients that they pull up via their deep root system. These weeds can be used in composting, but to prevent propagating the weeds, you should take some precautions. Some weeds can go to seed even after they are pulled from the ground, so to prevent this, let them dry in the sun for three to four days. After they have dried, put them into a hot compost pile (at least 135 degrees) and let them cook at that temperature for several days to kill off the seeds and roots. Chapter 5 describes how to take your compost pile’s temperature.

The following table compares the various types of compost systems, and lists some of the pros and cons of each type.

|

Type |

Pros |

Cons |

|

Pile or heap (slow/warm or cool) |

Easy to use. Little effort to maintain. Can add ingredients as they are accumulated. |

Takes a year or more to make compost. May smell. May leach nutrients. |

|

Pile or heap (fast/hot) |

Makes compost quickly. Kills weeds and some pathogens. Nutrients leached more slowly. |

Requires a large amount of material in the beginning. Takes a lot of effort to turn and maintain the pile. |

|

Stationary box |

Looks tidy (good for urban areas). Produces compost relatively quickly if well maintained. |

Box must be built or purchased. May be hard to turn contents. |

|

Tumbler |

Easy to use and aerate. No leaching of nutrients. |

May be expensive to buy. Works best if you fill it all at once. |

|

Pit or trench |

Relatively simple to do. No building or purchase necessary as long as you have a shovel. |

Only nourishes a small patch of land. Does not store much waste. |

|

Sheet |

Good for large areas. Consumes a lot of material. No purchase or building necessary. |

Requires effort to plant the crop then to till or turn material into the soil. Takes up to a season to decompose. |

|

Trash bag |

Inexpensive and easy to do. Can be done year-round and indoors. |

Anaerobic process will smell bad. May attract pests. |

|

Vermicomposting |

Easy to do. Uses food waste continuously. No smell. |

Requires some investment to build or buy a worm bin. Need to ensure worms are properly fed and kept at the right temperature. |

In the next chapter, you will explore the science behind composting. What actually happens in the compost pile to turn scraps into compost? How do bacteria and insects contribute to the process? How can you speed up composting or slow it down?

Case Study

Kimberly Wolterman, co-owner and vice president

Organic Resource Management, Inc.

13060 County Park Road, Florissant, MO 63034

“I am co-owner of a commercial composting business and also compost at home. Because we own a commercial composting facility, we can easily dispose of the leaves generated by our numerous trees and obtain finished compost whenever we need it.

We also keep a compost bin in the backyard. It is a simple, chicken-wire bin, but it gives us a place to recycle trimmings off plants and other yard waste. It is a slower process of decomposition, but it ultimately gets the job done, proving that you do not have to pay a lot of money for a composting system.

We have had a vermicompost bin in our house for the past ten years. We initially started a bin because we go to schools and give presentations on composting, and the worms provide a great visual of the composting process. Plus, the kids love the worms. When I take our worm bin into classrooms, I always allow time for the children to feel the compost and look closely at the worms. My favorite moment is when they realize what they have their hands in, and go, ’Ewwwww, worm poop!’

Both of our own children used the worm bin in science fair projects, and this year my great niece used it as well. From a recycling standpoint, it is amazing how much food waste the worms can consume. This prevents it from being placed in the landfill or sent down the garbage disposal. We use the worm castings to enrich the soil of our potted plants and collect the excess liquid from the worm bin to use as compost tea for the plants.

Composting is pretty much a no-brainer. It is the right thing to do for the environment; it does not require that much work; and you get a beautiful product that enhances your garden for free. It means a lot to me to know that I am keeping a valuable resource out of the landfill while at the same time being able to produce a product that enhances my plants and my gardens. We use compost in all of our planting beds and in all our pots containing vegetables, herbs, and annuals. Every time we cut in a new bed, we enrich the soil with compost prior to planting.

Composting happens every day in nature. Anyone can set up a compost bin, because it is a very basic process. You can simply toss grass clippings, leaves, and other yard debris in a heap and let nature do the rest, or you can set up a more sophisticated system to speed the process along. Either way, you can help the environment and your gardens at the same time. For me, the most difficult part for composting is turning the compost pile, which can be a challenge when using the single bin, chicken-wire system.

Why should we care about composting? In the United States, 12 percent of the landfill space is taken up by yard waste and 11 percent by food waste. By doing our part in recycling our own yard trimmings and food waste, we can save landfill space and help reduce methane production in landfills. All that, and you end up with a beautiful product that will improve your soil structure by adding organic matter. What’s not to love?”

Why should we care about composting? In the United States, 12 percent of the landfill space is taken up by yard waste and 11 percent by food waste.