Postcard photo of Camden, circa 1929 (RCA building is in bottom-center foreground with tower). Courtesy of Frederick O. Barnum III , author of His Master’s Voice in America.

Part II

Revival

CAMDEN ’S TALKING MACHINES

The sound of traditional folk and folk revival music came to life in Camden during the early years of the twentieth century. This was the place where Cecil Sharp, Paul Robeson, Carl Sandburg, the Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers and Woody Guthrie all had important recording sessions at the Victor studios. Taken as a whole, the Camden sessions form a foundation for American folk revival music and created waves of music traditions. In the ensuing years, other internationally renowned artists passed through New Jersey to perform and record, touching lives along the way. Their efforts reverberated inside and outside the Garden State, as they crafted lyrical songs and addressed social and political issues that guided the folk revival movement.

As detailed in two online essays—“Victor Talking Machine Company, Eldridge Johnson and the Development of the Acoustic Recording Process” and the David Sarnoff Library’s “The Victor Talking Machine Company”—Eldridge Reeves Johnson, on October 3, 1901, merged his Consolidated Talking Machine Company with the Berliner Gramophone Company to create the Victor Talking Machine Company. Six years later, Victor’s main studio opened in Camden, at the southwest corner of Front and Cooper Streets. In February 1916, Victor christened a new executive building at Front and Cooper Streets. Two years later, the company purchased the Camden Trinity Church at 114 North Fifth Street and converted it to a studio. Recording sessions began at the church studio on February 27, 1918. Fred Barnum, who wrote a history of the Victor Company, His Master’s Voice in America, said Trinity Church quickly became the preferred studio because of its superior acoustics.

Postcard photo of Camden, circa 1929 (RCA building is in bottom-center foreground with tower). Courtesy of Frederick O. Barnum III , author of His Master’s Voice in America.

Eldridge Johnson sold his company to RCA in 1927. Barnum said the Camden facility had phased out studio recordings by the mid-1940s. Johnson was born on February 6, 1867, and died on November 14, 1945. An online research paper by Paul D. Fischer, “The Sooy Dynasty of Camden, New Jersey: Victor’s First Family of Recording,” describes the work of three brothers, Harry, Raymond and Charles Sooy, employees of the Victor Talking Machine Company, “as the unsung pioneers of popular music production.”

Author and historian Leonard DeGraaf, an archivist at Thomas Edison National Historical Park in West Orange, said the famed New Jersey inventor, working at his Menlo Park lab in Middlesex County, received a patent for the ingenious tinfoil phonograph on February 19, 1878. Edison did envision the device as a source of entertainment, although DeGraaf pointed out that this early version of the phonograph “would require numerous technological improvements before it could provide a decent musical experience.”

GATHERING SONGS , SOWING SEEDS

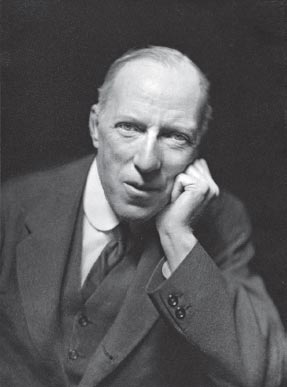

British folklorist Cecil J. Sharp (1859–1924), a scholarly collector of ballads and folk dances, arrived in New York City on January 1, 1915. An entry in his diary on that date, transcribed by the London-based Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (part of the English Folk Dance and Song Society), states that Sharp “greeted the New Year in bed, being unable to sleep for the pandemonium in the streets. All New York seemed to be blowing tin horns, letting off explosives, rattling, etc.”

The first folk music revival emerged as a result of Sharp’s efforts in documenting folk songs in the United States and England. Maud Karpeles was his loyal assistant. Sharp is a key figure in the English folk revival, along with other British folklorists who preceded him, such as Lucy Broadwood, Frank Kidson and Sabine Baring Gould, all of whom were collecting and publishing folk songs during the late 1800s, as pointed out by a representative from the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Sharp’s accomplishments included establishing the English Folk Dance Society in 1911; compiling the book English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, published in 1917, as a joint effort with American folklorist Olive Dame Campbell; and producing recordings at the Victor studios in Camden.

Sharp’s work gathering folk songs in the United States took place during three visits, from 1915 to 1918. “In all, he collected 1,625 items. Sharp’s aim was to collect songs of English origin [in America] and he did this very successfully,” the Williams representative stated. He added that, generally speaking, Sharp was less interested in collecting songs and tunes of American origin, although he may have picked up some by accident.

Cecil Sharp. Courtesy of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, English Folk Dance and Song Society, Cecil Sharp House, London.

On April 15, 1915, an apprehensive Sharp wrote that he had taken the train from Philadelphia to Camden to supervise the Victor recordings. “Great fiasco—scores badly written.” Despite Sharp’s concerns, the session produced ten recordings by the Victor band, a “light orchestra” composed of “19 men personally supervised by Cecil J. Sharp,” according to information provided by the Discography of American Historical Recordings, a database of master recordings made by American record companies during the 78 rpm era and part of the American Discography Project—an initiative of the University of California–Santa Barbara and the Packard Humanities Institute. The list of songs from the session included titles such as “The Butterfly,” “Row Well, Ye Mariners” and “Goddesses.”

Sharp traveled to Lincoln, Massachusetts, in June 1915 to meet with his main benefactor, Helen O. Storrow. In his June 19 diary entry, Sharp wrote that, while at the Storrow home, he met with folklorist Mrs. John (Olive Dame) Campbell of Asheville, North Carolina, “who showed me her collection of ballads, which I found most interesting.” Three books—Folk Dancing by Erica Nielsen; Hoedowns, Reels and Frolics: Roots and Branches of Southern Appalachian Dance by Phil Jamison; and Cecil Sharp: His Life and Work by Karpeles—describe the meeting at the Storrow home. Campbell invited Sharp and Karpeles to visit Asheville. They arrived by train in July 1916, and this collaboration with Campbell became an extended project for which Sharp and Karpeles spent weeks doing field research in remote southern Appalachian communities, all of which led to Sharp’s 1917 book.

According to an online essay by Digital Heritage, Campbell believed that the inhabitants of the Southern Appalachians were still singing the traditional songs and ballads handed down by their English and Scottish ancestors—tunes they brought with them to America. Sharp’s research demonstrated how people tenaciously cling to their beloved folk songs, even when it means crossing an ocean to find a new home. The nostalgic tunes, embedded in the hearts of these immigrants, helped to ease their transition and fashion a new culture in a foreign land.

Sharp’s efforts would have a lasting effect on American music. He influenced a generation of social historians, encouraging them to become more active in researching their respective folk cultures. The Digital Heritage essay stated that, in the wake of Sharp’s work, “modern country music was borne of traditional ballad recordings produced in the heart of southern Appalachia. Music festivals, concert performances, and competitions began appearing nationally and throughout the region.”

Prior to his initial journey to Asheville, Sharp made arrangements for another recording session at the Victor studios in Camden. His March 7, 1916 diary entry states that he caught the 8:00 a.m. train in Philadelphia and arrived at the Victor studios at 10:30 a.m. “Thank heavens I had another conductor, one Mr. Rogers, who really was a musician and knew his work. Consequently I was able to finish off all the records.”

The Williams representative indicated Sharp oversaw three recording sessions at the Victor studios in 1915 and 1916, which included the arrangements of folk dance tunes that he had collected. “We know from the letters and diaries that Cecil Sharp had plenty of meetings with people at Victor and that he had worked on choosing and arranging material for the sessions.” The Camden sessions took place on April 15, 1915; November, 26, 1915; and March, 7 1916.

Sharp left many legacies, one of which was his belief that folk music should be part of public education curriculum. For Sharp, this was a priority, and he championed the cause. He was sowing seeds that would take root in the later years of the twentieth century, providing a foundation for the folk revival music phenomenon (and market) in America. Young students exposed to the joys of folk music would become receptive consumers and participants in the genre in their adult years.

A RAGBAG OF STRIPS , STRIPES AND STREAKS

President Lyndon Baines Johnson, in September 1967, during a memorial service for American poet Carl A. Sandburg (1878–1967) held at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., said Sandburg “was more than the voice of America; more than the poet of its strength and genius. He was America.”

Sandburg rose to national prominence in 1919, when his collection of poems, Cornhuskers, won the Pulitzer Prize. In addition to being a poet, Sandburg was a dedicated collector of American folk songs, which led to recording sessions at Victor studios in Camden. The Discography of American Historical Recordings documented two recording dates for Sandburg: a trial session of two songs on December 9, 1925, and a follow-up session on March 4, 1926. He sang and played guitar. The list of Sandburg’s tunes included a “Classical Guitar Song,” “The Boll Weevil Song,” “Negro Spiritual,” “Two Old Timers,” “Two Cowboy Songs” and “Two Hobo Songs.” Victor issued two selections, “Boll Weevil” and “Negro Spiritual,” on a single 78 disk.

Ronald D. Cohen, in his book Rainbow Quest: The Folk Music Revival and American Society, 1940–1970, described Sandburg as an “influential outsider.” Sandburg, Cohen said, “made an early contribution to folk music through his publications, records and public performances. His leftist politics and search for heroic, common themes in U.S. history led, perhaps naturally, to a love of folk music. He collected folk songs most of his life and…frequently performed during public lectures the spirituals and hobo, cowboy and jail songs he had zealously collected.” Sandburg’s major contribution to folk music, according to Cohen, was his 1927 book, The American Songbag. In the book’s introduction, Sandburg described his compendium, a collection of 280 songs:

The American Songbag is a ragbag of strips, stripes, and streaks of color from nearly all ends of the earth. The melodies and verses presented here are from diverse regions, from varied human characters and communities, and each is sung differently in different places. [The songbag] comes from the hearts and voices of thousands of men and women. They made new songs, they changed old songs, they carried songs from place to place, they resurrected and kept alive dying and forgotten songs.

A PEERLESS A&R MAN

Victor artist and repertoire (A&R) man Ralph Peer (1892–1960) traveled to Bristol, Tennessee, during the summer of 1927, in search of new folk and country music talent—a now-legendary excursion in the annals of American music. Peer set up a temporary recording studio on State Street in downtown Bristol, the boulevard that was directly on the Tennessee/Virginia state line. An online essay by Ted Olsen, written for the Library of Congress, and the book Encyclopedia of American Gospel Music, edited by W.K. McNeil, recount how these audition sessions, which ran from July 25 to August 5, led to Peer’s discovery of the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers and how he brought them to record in Camden.

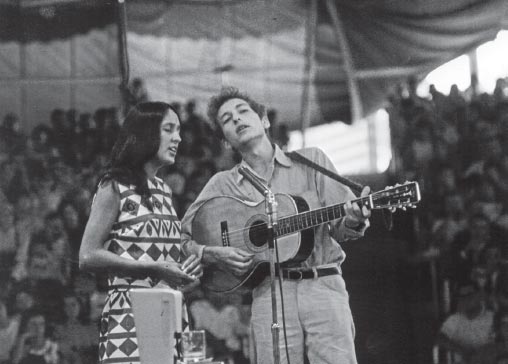

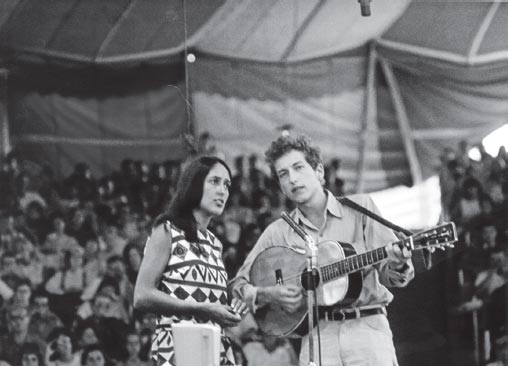

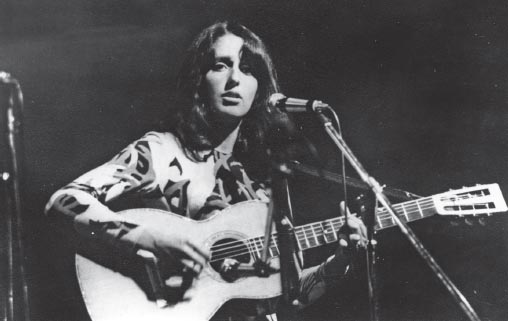

The Carter Family—Alvin Pleasant (AP) Delaney, his wife, the former Sara Dougherty and Maybelle (Addington) Carter, the wife of AP’s brother Ezra—through their Victor recordings, emerged as pioneers of American roots music. They became a standard for aspiring artists such as Woody Guthrie, Doc Watson, Johnny Cash, Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. Decades after their first recordings, they were inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame, the Grammy Hall of Fame and the International Bluegrass Hall of Fame.

Sara, Maybelle and AP recorded six tunes for Peer on August 1 and 2, 1927, during the Bristol audition. The songs, according to a listing by the Discography of American Historical Recordings, were “Little Log Cabin by the Sea,” “Bury Me Under the Weeping Willow,” “Poor Orphan Child” and “The Storms Are on the Ocean” on August 1 and “Single Girl, Married Girl” and “The Wandering Boy” on August 2. McNeil wrote that, on November 4, 1927, Victor released the first Carter Family record, Poor Orphan Child, which became a hit. “Peer wasted no time in getting the Carters back into the studio,” and paid the expenses for them to come to Camden, according to McNeil. Sessions in Camden on May 9 and 10, 1928, yielded twelve tunes, including “John Hardy Was a Desperate Little Man,” “Anchored in Love” and “Wildwood Flower.” The songs and their arrangements, instrumentation and vocal harmonies would become benchmarks for the twentieth-century folk revival sound.

The family returned to Camden on February 14 and 15, 1929, to record twelve more songs, including “Diamonds in the Rough,” “My Clinch Mountain Home,” “I’m Thinking Tonight of My Blue Eyes” and “Sweet Fern.” Information on the American Experience website stated that Peer “had hit pay dirt” with the Carter Family. By 1930, they had several national hits and had sold more than 700,000 records. “By 1930 the Carters had broadened their repertoire to include modern-sounding songs…as well as African-American church music.”

Peer, a champion of American roots music, knew the lay of the land in the Garden State, having resided in East Orange during most of his years as an A&R man, from 1919 through the 1930s. He joined Victor in 1926 and originally was employed at the Otto Heineman Phonograph Supply Company, which became General Phonograph, with a record label named Okeh, according to the book Ralph Peer and the Making of Popular Roots Music by Barry Mazor. Mazor wrote that General Phonograph had a manufacturing operation in Newark. “Peer’s leisure time, limited as it was, tended to involve the close-knit family of General Phonograph and Okeh employees around East Orange.”

“In the course of his career, Peer singled out a historic list of musical jewels and placed them in settings that got our attention,” Mazor continued. “Ralph Peer developed and executed a business strategy that bordered on an aesthetic. At its core was a simple idea: untapped roots music—music that evidences rich history, that has moved a specific people of some distinctive place and culture and reflects their lives and rhythms—could appeal to much broader audiences by far, if handled properly as a commercial musical proposition.”

THE FATHER OF COUNTRY MUSIC

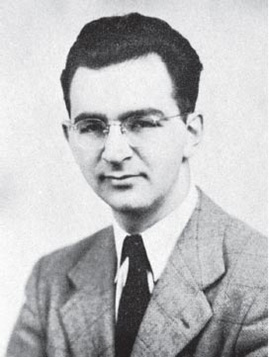

On November 30, 1927, Jimmie Rodgers arrived at the Victor studios in Camden, having accepted an invitation from Peer. Like the Carter Family, Rodgers had met Peer in August of that year in Bristol for an initial demo session. Rodgers recorded four tunes in the Camden studios, including “T for Texas,” also known as “Blue Yodel Number 1,” which went on to become a national hit and featured his signature country yodel.

Immortalized as “the Father of Country Music,” Rodgers admittedly was not a folk revival singer, but his music would have a direct influence on important revival musicians like Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan. In his book Meeting Jimmie Rodgers: How America’s Original Roots Music Hero Changed the Pop Sounds of a Century, Mazor pondered the question of whether Rodgers should be considered a “hero” in the folk revival music genre. Mazor wrote that, with “little equivocation,” Rodgers didn’t want to be a folk singer. During Rodger’s brief career as a professional musician, he demonstrated a

pattern of choices…that steered him clear of the folk minstrel job description…and kept his music outside of the urban folk song bag. Yet it is not surprising, in view of the eventual emergence of folk revival heroes who owed him something, that Jimmie himself is sometimes claimed as a hero of American folk music. In the places where the makers and consumers of unmediated down-home music lived and struggled to get by, Jimmie Rodgers’ music was out there, being played and adapted.

Rodgers was a dedicated Martin Guitar user. Dick Boak, the Martin Guitar historian, said Rodgers is part of the unseen thread that traces the development of folk revival music, as mentioned in Part I. According to Boak, the twelve-bar blues that Rodgers helped pioneer serves as a foundation for folk revival music as well as rock-and-roll. “Jimmie’s early records set the groundwork for everything that followed,” Boak said. “All genres of music interconnect and influence each other.”

The distinctive vocal style of Rodgers, molded by regional influences, much of it rooted in a blues tradition, is what set him apart from other performers in his day, according to Mazor. Rodgers’s singing and phrasing “was loose and comfortable, closely akin to the way he spoke. At times it was nearly conversational. His style contrasted sharply with the old-school, declamatory style of vocalizing that was still holding on in pop operetta and early Broadway shows.” Mazor wrote that record buyers and radio and sound-film audiences were seeking “something from the American vernacular that sounded more intimate, not designed to be boomed across a concert hall. Rodgers’ performing style was about emotional immediacy. He sang the lyrics of a song…communicating the drama of the story as it unfolded.”

Jimmie Rodgers. Courtesy of C.F. Martin Archives, Nazareth, Pennsylvania.

Following that initial November 30, 1927 recording session with Victor, Rodgers had five more studio dates in Camden, the last being on August 15, 1932, according to information posted by the New World Encyclopedia website. Rodgers was born on September 8, 1897, in Meridian, Mississippi, and died in New York City on May 26, 1933.

THE DUSTIEST BALLADEER

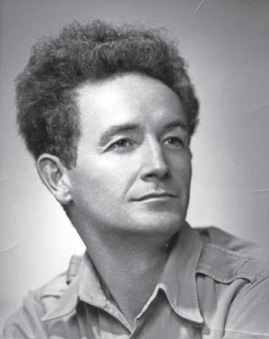

Woody Guthrie landed in New York City during a winter storm on February 16, 1940. The book Woody Guthrie: American Radical by Will Kaufman chronicled Guthrie’s arrival and early activities in the Big Apple. While living in California, Guthrie met Hollywood actor and left-wing activist Will Geer. (Geer is best known for playing Grampa Walton in the 1970s TV series The Waltons.) Geer invited Guthrie to join him in New York. Guthrie, who had been living in Pampa, Texas, sold his car, paid for a bus ticket to Pittsburgh and then hitchhiked the rest of the way. Geer, at the time, had the lead role of Jeeter Lester in the Broadway production Tobacco Road, which was playing at the Forrest Theater.

Woody Guthrie on the New York City subway, circa 1943; photo by Eric Schaal. Courtesy of Woody Guthrie Publications Inc. Used by permission.

Ed Cray, in his book Ramblin’ Man: The Life and Times of Woody Guthrie, described Geer as a prominent organizer of left-wing causes, traveling the country to support striking workers. Geer booked Guthrie to perform at Manhattan’s Mecca Temple on February 25, 1940, a rally to benefit Spanish Civil War refugees. This rally was a prelude to Guthrie’s involvement in a major concert one week later. Cray wrote that Geer had made arrangements with the producers of Tobacco Road to use the Forrest Theater (today known as the Eugene O’Neill Theater, located on West Forty-Ninth Street) for a concert to benefit the John Steinbeck Committee for Agricultural Workers.

The concert, dubbed “A Grapes of Wrath” evening (the name borrowed from Steinbeck’s classic 1939 American novel), was held on March 3, 1940, presented by Geer and the Theatre Arts Committee of New York. In retrospect, the concert was a pivotal moment that helped to launch the American folk revival music movement of the twentieth century. “There had been other ‘folk’ music recitals, but this would be remembered as the first really important one, the first before a large, mainstream audience,” Joe Klein wrote in his book Woody Guthrie: A Life.

The New York–based Daily Worker newspaper, in its March 1, 1940 edition, provided preview coverage of the show, a “ballad-sing benefit,” with the headline “Broadway Progressives Aid American Relief.” The newspaper reported that proceeds for the benefit would go “entirely for the aid of the now-famed ‘Okies’. They are the ‘refugees’ from the ravages of our native landlords and bankers, who are waging as merciless a war against these people as any battle taking place in Europe.” The article went on to say that the concert, in the “true American tradition,” would present

some of the finest and most authentic folk and working class artists to be found in this country. Along with Geer on the Grapes of Wrath program, there will appear a veritable bumper crop of talent, including “Woody,” a real Dust Bowl refugee and discovery of Geer’s who was brought to New York recently, especially to appear on the program. Woody is a folk singer who chants not only the genuine songs of this region, but composes unique and moving ballads of social and topical nature.

Below the Daily Worker article was a two-column photo of a guitar-strumming Guthrie with this caption: “Woody—that’s the name. Straight out of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, this troubadour will sing ballads of the people at the Forrest Theater affair.”

The concert also brought together Guthrie, Alan Lomax and Pete Seeger. Cohen, in his book Rainbow Quest, said Pete Seeger, born in New York City on May 3, 1919, “dropped out of Harvard at nineteen and hit the road. The [Grapes of Wrath] concert marked Seeger’s inaugural public performance, a nervous rendition of one song.” Cray and other sources identified the tune as “The Ballad of John Hardy.” Seeger had left Harvard University in the spring of 1938 and a year later was hired by Lomax as an intern at the Library of Congress’s Archive of American Folk Song. It was Lomax who urged Seeger to perform at the Forrest Theater show.

A copy of the Grapes of Wrath program, provided by the Woody Guthrie Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, identified the lineup of performers. In addition to Guthrie and Seeger, the list included Geer, Aunt Molly Jackson, Lomax, the legendary blues singer Leadbelly, Burl Ives, the Pennsylvania Miners and the Golden Gate Quartet. Guthrie, as listed in the concert program, performed “Do Re Mi,” an untitled blues tune and an antiwar song titled “Why Are You Standing in the Rain?”

Cray wrote that Alan Lomax was intrigued by Guthrie—both his music and persona. Alan, the son of pioneering folklorist John Avery Lomax, “was an enthusiastic promoter of American folk music. By March 1940, and the time of the Forrest Theater concert, Alan was a driving force in the burgeoning revival of American folk song in big cities.” He served as the “assistant in charge” of the Library of Congress’s Archive of American Folk Song. According to Cray, Lomax collaborated with Geer and selected the performers for the Grapes of Wrath event, except for

Will Geer’s friend from California, this bushy-haired Okie with the exaggerated drawl [meaning Guthrie]. Lomax was overwhelmed. Guthrie was not only singing folk songs, he was writing his own; songs that reflected Lomax’s own belief in a new America, a nation in which the working people expressed themselves through folk culture. In Guthrie, Lomax heard a real ballad maker, a man who wrote in the people’s idiom. Guthrie was a natural genius.

DUST BOWL BALLADS

In his book, Ronald Cohen observed that by 1940, folk and folk revival musical idioms had gained the attention of record labels. There was an expanding, diverse audience for the music, as demonstrated by the popularity of the Forrest Theater event. “Major record companies recognized the growing urban interest in native folk styles.…The long-smoldering question of authenticity and style versus substance would continually engage folklorists, music critics and fans throughout the century.”

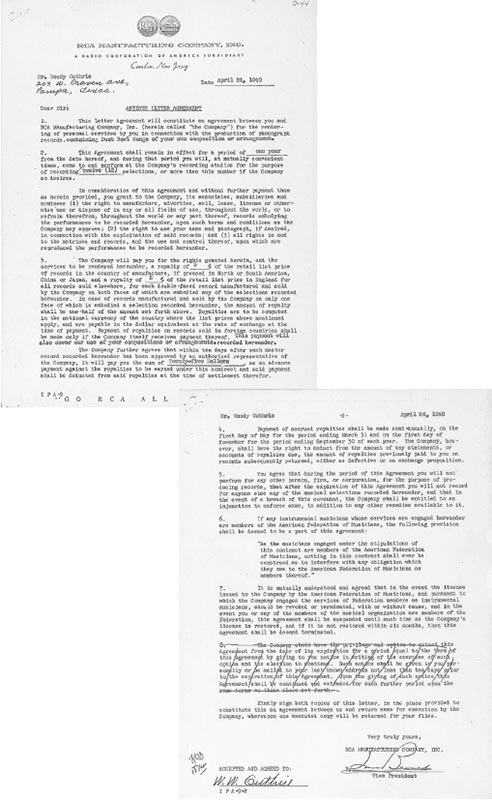

The fast-paced sequence of events involving Guthrie in the span of three months—arriving in New York, performing at the Grapes of Wrath concert, connecting with Lomax and Seeger—propelled Guthrie’s career as a recording artist. Cray’s book and the blog Woody Guthrie Dust Bowl Ballads tell the story of how RCA Victor producer Robert P. Wetherald approached Lomax about doing a “folk” record. Lomax quickly nominated Guthrie for the opportunity, describing Woody “as our best contemporary ballad composer.” During this early period of his career, Guthrie often was referred to as a “balladeer.” Guthrie signed an “Artists Letter Agreement” with RCA Manufacturing Company Inc., dated April 24, 1940, a copy of which is on file in the archives at the Library of Congress. Two days later, Woody Guthrie arrived at the RCA studios in Camden to record his Dust Bowl Ballads album. Most likely, he traveled by train, toting his guitar case and a notebook full of tunes. This would be Guthrie’s first commercial studio recording session.

This is Woody Guthrie’s two-page contract, dated April 24, 1940, for his first studio album, Dust Bowl Ballads, recorded at the RCA studios in Camden. Courtesy of the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Used by permission.

Guthrie’s Dust Bowl Ballads album and the Grapes of Wrath concert are cornerstones in the American folk revival tradition. The recording sessions in Camden took place on April 26 (the primary session) and May 3. The list of tunes included “Talkin’ Dust Bowl Blues,” “Tom Joad,” “The Great Dust Storm” and “I Ain’t Got No Home in This World Anymore.” The songs on the album were Guthrie’s eyewitness accounts of Midwest dust storms during the depths of the Great Depression.

Released in July 1940, Dust Bowl Ballads inspired generations of musicians. However, authors Cray and Klein wrote that the album initially received little critical attention. According to Klein, “the most perceptive review came from Howard Taubman in The New York Times: These albums are not a summer sedative. They make you think; they may even make you uncomfortable.”

During the 1940s, Guthrie was in demand to sing at labor rallies and union halls. Will Kaufman, in his book Woody Guthrie: American Radical, wrote that on February 9, 1947, Guthrie was invited to sing for the United Electrical Workers at the Phelps-Dodge Plant in Elizabeth. The workers had just concluded a bitter eight-month strike. Guthrie did perform, but this date tragically coincided with the death of his four-year-old daughter, Cathy Ann, who perished in an accidental fire at the Guthrie home in Coney Island, New York.

THE LIVE WIRE IN NEWARK

The October 21, 1949 edition of the Jewish News reported that Guthrie would present a song and lecture program on the development of American folk music at the Jewish Community Center in Newark, part of the center’s “Meetings on Mondays” series. Years later, this concert would come to be known as the “Live Wire” performance. The event took place on October 24, 1949. The Newark Evening News, in its October 24, 1949 edition, previewed the event, saying Guthrie “would perform tonight at 8:15 p.m. in Fuld Hall” at the Newark center. The article described him as the “author of hundreds of folk songs” and mentioned his service during World War II as a merchant marine (and in the army). “Guthrie’s wife, Marjorie Mazia, a dancer, will give a commentary on her husband’s songs between his offerings.” The Live Wire CD booklet indicates that “no more than fifty people” attended the Monday night program.

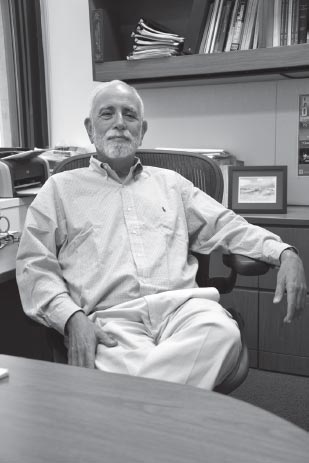

Rutgers student Paul Braverman, circa 1949. Courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, New Brunswick.

Marjorie was a dancer with the Martha Graham Dance Company and taught classes at the Newark center. One member of the audience on that Monday night was a Rutgers University student named Paul Braverman, who had brought with him a wire-recording device. According to the accompanying booklet for the 2007 Live Wire CD, Braverman, more than fifty years after attending the performance, discovered the wire recordings in a closet at his home in Florida. He donated them to the Woody Guthrie Archives in 2001. The CD was released in 2007, and it won the 2008 Grammy Award for Best Historical Album. The Newark performance represents the only known full-concert recording of Guthrie. Song titles on the CD performed that night in Newark include “Black Diamond,” “The Great Dust Storm,” “Talking Dust Bowl Blues” and “Tom Joad.” Braverman died in 2003, according to a December 19, 2007 Associated Press story.

Kurt Sonnenfeld, a Queens, New York resident who worked at the Newark center and was a friend of Marjorie, recalled seeing Woody at the center on several occasions. Sonnenfeld, who, along with his family, came to the United States in 1940 to escape the growing Nazi threat spreading throughout Europe, was a resident of Manhattan in the late 1940s. He would take the bus to Newark three days a week, working as a supervisor for youth groups at the Jewish center. “My friends and I, we liked folk songs and we went to concerts and political rallies in New York City,” Sonnenfeld said in a February 2015 phone interview. “We were sympathetic to progressive causes. Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and Paul Robeson—they were our heroes, musically and politically.” Sonnenfeld confessed that he wasn’t able to attend the Live Wire concert.

Throughout the 1950s, Guthrie’s health deteriorated due to the effects of Huntington’s disease. In the mid-1950s, he spent two years at Brooklyn State Hospital. Cray wrote that Guthrie was released from the hospital and made his way to New Jersey, where he was arrested in the Morristown area on May 28, 1956, “wandering aimlessly on a highway in a dazed condition.” Guthrie was committed to the New Jersey Hospital at Greystone Park, a sanatorium in Morris Plains, on May 29, 1956, according to his summary medical report reproduced in the book Woody Guthrie’s Wardy Forty by Phillip Buehler. During his days at Greystone, Guthrie was befriended by two devoted fans, Bob and Sidsel Gleason, and he spent weekends at their East Orange apartment.

Guthrie died at Creedmoor State Hospital in Queens, New York, on October 3, 1967 at the age of fifty-five. Author and historian Nat Hentoff, in a magazine article written three years before Guthrie’s death, quoted John Steinbeck on the significance of the Dust Bowl balladeer’s legacy. “There is nothing sweet about the songs [Guthrie] sings, but there is something more important for those who will listen. There is the will of the people to endure and fight against oppression. I think we call this the American spirit.”

Woody Guthrie publicity photo. The picture is dated July 1948 and was taken at the studio of Oscar Stechbardt, which was located at 614 Central Avenue in East Orange. Courtesy of the People’s World, Chicago, via the Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at New York University.

I SHOULDN ’T HAVE BEEN SURPRISED

Josh White, the silky-voiced guitarist, arrived in the Big Apple in 1931. White’s discography as a folk revival and blues singer began in 1929, and he recorded throughout the 1930s. In late 1939, White was cast in a supporting role in the Broadway production John Henry, with Paul Robeson in the lead role. The production opened on January 10, 1940, at the Forty-Fourth Street Theater but lasted only seven performances, according to The Complete Book of 1940s Broadway Musicals by Dan Dietz.

Music historians point to “John Henry” as the most popular song in American folk music. John Henry is depicted as a powerful, brave, defiant figure. Several have attempted to identify the man behind the legend. One author believes he came from New Jersey. Scott Reynolds Nelson, in his 2006 book Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, the Untold Story of an American Legend, did research at the Library of Virginia, examining records from the old Virginia Penitentiary, and discovered John William Henry, a “colored man” who was received at the prison (at age nineteen) on November 16, 1866. According to those files, he was born in Elizabeth and was serving a ten-year sentence for “housebreak and larceny.” Nelson wrote that the prison register shows New Jersey’s John Henry was contracted to join Virginia’s Chesapeake & Ohio (C&O) Railroad in 1868. Records also indicate that convicts and steam drills worked side by side, as described in the folk song.

While the Broadway production of John Henry had a short run, this experience connected Josh White with other musicians in New York. Author Elijah Wald, in his book Josh White: Society Blues, wrote that “the New York Left was certainly heady company for black blues singers. In the 1930s, Josh’s fans had been rural, southern blacks; in the 1940s they were white, urban and often quite wealthy café-goers.” Wald wrote that this new audience “lionized and applauded” White’s stance on racial and social justice issues.

In 1940, White came to New Jersey, a visit that would inspire a song. He went to see his brother Bill, who was in Fort Dix taking part in basic training for the army. Wald, during an August 2015 phone interview, said he learned about the story from notes given to him by White’s manager. Wald said White also recounted the tale during an October 29, 1944 radio interview on the broadcast New World A’Coming: Music at War. White drove out to Fort Dix and was shocked to witness the segregated conditions that existed between white and black recruits. “Well, I shouldn’t have been surprised,” Wald quoted White, “but I wasn’t thinking. I felt that once we were preparing to fight an enemy, we’d forget about all these things.” White returned to New York, still disturbed by this experience. “I went home and couldn’t sleep, so I wrote a song. It wasn’t a good song, a good tune or a good lyric, but I said what I had to say, what I wanted to say about Uncle Sam.”

Collaborating with Harlem Renaissance poet and composer William Waring Cuney, White wrote the tune “Uncle Sam Says,” which appeared on his 1941 recording Southern Exposure: An Album of Jim Crow Blues. The song also was released as a single. Wald, in an article he penned for Living Blues magazine (“Josh White and the Protest Blues”), said the album garnered reviews in mainstream media, including a story in the New York Times. “This coverage all concentrated on the political content of his music…the burden of these songs is the bitter lot of the Negro seeking his meed of equality,” Wald wrote, paraphrasing the Times review. Despite White’s initial misgivings, Wald pointed out that “Uncle Sam Says” was “the most significant song on the album…a cutting 12-bar critique.” The song’s lyrics lament that, even when the United States was pulling together to fight the war in Europe, African Americans, serving honorably and courageously in the armed forces, still were forced to endure the segregated restrictions and bigotry imposed on them by the Jim Crow era.

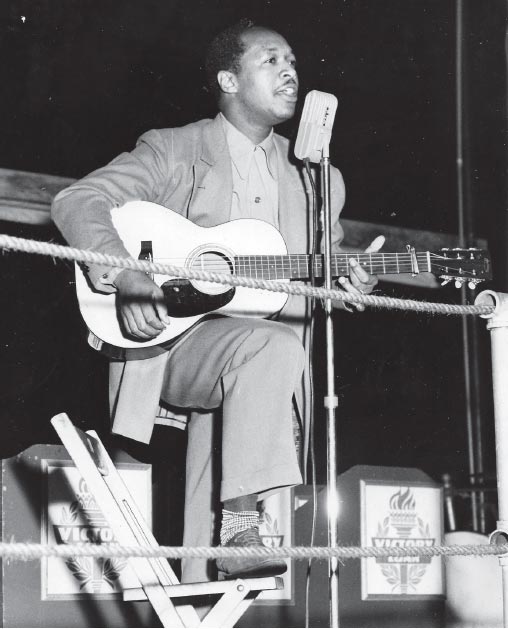

This photo of Josh White Sr. was taken at a war bond rally in New York, circa 1942. Courtesy of Douglas A. Yeager Productions, New York. Used by permission.

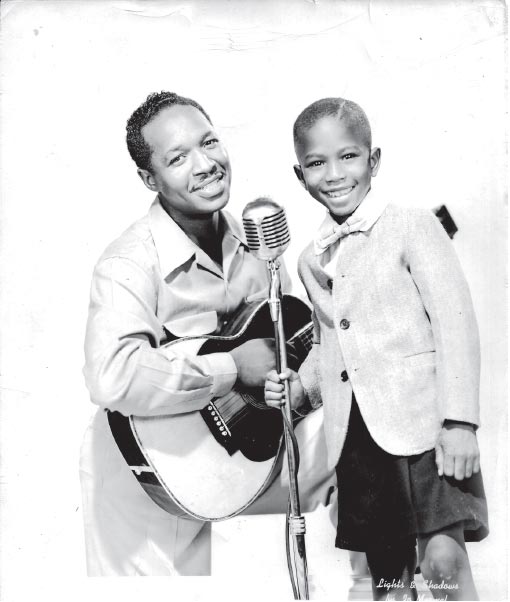

Beginning in 1944, Josh White Jr. and his dad began performing as a duo on New York radio broadcasts. In June 1998, the U.S. Postal Service issued a postage stamp in honor of Josh White Sr. Courtesy of Douglas A. Yeager Productions, New York. Used by permission.

Wald also discussed an obscure New Jersey episode for White—a recording session for a little-known studio, CES Recordings, located in Livingston, which purportedly took place on the evening of March 26, 1954. Though the story is somewhat murky, Wald said he culled together several sources, which indicated the session—eight songs—did take place and that the tunes were released by London Records in Europe and Period Records in the United States. The 1958 Period album Josh White Comes A-Visiting had White’s tunes on the album’s A side, paired with eight songs by Big Bill Broonzy on the B side.

The Period album notes described a session that started out with a degree of tension.

The night of the [recording] date Josh was leaving for Hollywood.…The first ten minutes were stretched as tight as a guitar string. Suddenly, Josh grinned. “This is going to be a good session,” he said quietly with a deep chuckle. It was! Josh took over the session with the result that had the feeling he and his friends had just dropped in on us from the road to spend a few hours of folksy music. We like this record. We like it because we think it is an honest picture of Josh White at his finest and “folksiest.”

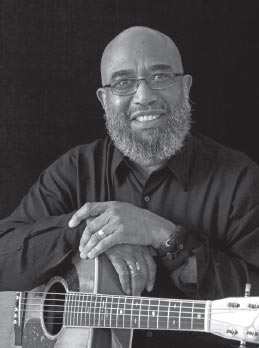

Josh White Jr. was the featured guest at the Hurdy Gurdy Folk Music Club in Fair Lawn at a concert held in December 2014 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his dad’s birth. Courtesy of Douglas A. Yeager Productions, New York. Used by permission.

White, who was born on February 11, 1914, in Greenville, South Carolina, and died on September 5, 1969, in Manhasset, New York, recorded albums throughout the mid-1960s, although earlier in his career he was a “blacklisted” artist due to his views on politics and civil rights. Ron Olesko’s “Folk Music Notebook,” an online article posted on December 1, 2014, by Sing Out!, reported that the Hurdy Gurdy Folk Music Club in Fair Lawn would honor White, marking the 100th anniversary of his birth, with a concert at the Fair Lawn Community Center on December 6, 2014. Josh White Jr., White’s son, a professional folk revival and blues musician, was the guest of honor for the performance.

PATERSON ’S BLACKLISTED SON

Writing in the July 14, 1942 edition of the New Republic, Paterson native Millard Lampell offered thoughts about the power and influence of music. “What makes good songs?” Lampell asked in his article.

The answer is in folk music. The Spanish loyalists sing folk songs. The Red Army is singing folk songs and so are the Chinese. Folk songs [are] in the people’s language and in the people’s tradition. Songs made up yesterday and this morning. It’s about time for somebody to slap down the idea that folk music means archaic ballads and hill tunes. Folk music is a living art of working people, writing about their own lives. It means assembly lines, wives and kids, love, and the sound of machines. It means saying it straight, with no tricky rhymes, strained puns and tortured metaphors. It means writing simply, with the color and imagery of an ordinary working man’s speech.

Lampell’s essay decried what he considered to be restrictions imposed by the American music industry on thoughtful songs. “The whole vast network of music distribution is a slick machine,” he wrote. “Standards are set by the music publishers and the songwriters accept them meekly…and wonder what the hell rhymes with ‘champagne.’ Record companies turn out whatever songs the ‘name’ performers want to record, and ‘name’ performers use the songs music pluggers hand them.” Despite the hurdles, Lampell wrote that there was reason to be hopeful, saying he was reassured by the graceful simplicity and good taste of everyday people. “Occasionally the good songs get through. And sometimes, when enough people sing them loud enough, they echo up into the chromium and leather offices of the radio chains and record companies.”

Millard Lampell was born in Paterson on January 23, 1919. His parents, Bertha and Charles Lampell, had come to America from Austria and operated a millinery shop in the Silk City. Lampell grew up in the aftermath of Paterson’s 1913 silk millworkers’ strike, a significant chapter in America’s labor history. He attended School 20 and graduated from Eastside High School. He arrived at the University of West Virginia in the fall of 1936, going there on a football scholarship. A biography on Lampell, posted on the website Allmusic.com, stated that during his years as a student at West Virginia, Lampell “became fascinated by the rural folk music that he heard, and his social conscience evolved as well in the mid-1930s, especially after he visited the home of a college roommate and discovered the conditions under which coal miners worked and lived. He also saw first-hand the battles waged between the United Mine Workers and the mine owners.”

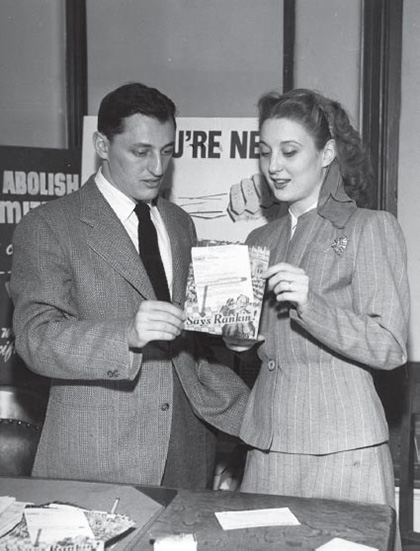

Millard Lampell pictured with Hollywood actress Betty Garrett (1919–2011) at a 1946 Citizens to Abolish the Wood-Rankin Committee rally held in Manhattan. The Wood-Rankin Committee was associated with the U.S. House Committee on Un-American Activities. Courtesy of the People’s World, Chicago, via the Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at New York University.

Beginning in 1940, Lampell wrote articles for the New Republic and became acquainted with another New Republic author named Lee Hays. Doris Willens, in her book Lonesome Traveler: The Life of Lee Hays, said that the two young writers connected through a series of letters of mutual admiration. It was through this correspondence that they decided to meet in New York. Willens wrote that they hit it off well and decided to become roommates, getting an apartment in the Chelsea section of Manhattan. Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger also were in town during this period, and through a mutual friend, Lampell and Hays met Seeger and Guthrie, which led to the formation of the Almanac Singers.

Tender Comrades: The Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist by Patrick McGillian and Paul Buhle includes a chapter on Lampell, in which he described himself as “a storyteller from an early age.” During his university years, he said he became interested in “one particular subject—fascist movements in America.” After graduating from the University of West Virginia, Lampell said he hitchhiked to New York with the aim of becoming a writer. Lampell, in an op-ed piece (“I Think I Ought to Mention I Was Blacklisted”) that appeared in the August 21, 1966 Sunday New York Times, shared his experiences:

In 1940 I had come up from West Virginia and, with Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie and Lee Hays, formed a folk singing group called the Almanacs.…There wasn’t exactly a clamor for folk singers and we were grateful for any paid bookings we could get. Mostly we found ourselves performing at union meetings and left-wing benefits for Spanish refugees, striking Kentucky coal miners and starving Alabama sharecroppers. We were all children of the Depression, who had seen bone-aching poverty.…We had learned our songs from gaunt, unemployed Carolina cotton weavers and evicted Dust Bowl drifters.…We were for the working stiff, the underdog and the outcast and those were the passions we poured into our songs. We were all raw off the road and, to New York’s left-wing intellectuals, we must have seemed the authentic voice of the working class. Singing at their benefits kept us in soup and guitar-string money.

THE ALMANAC TRAIL

The Almanacs performed at Madison Square Garden on May 21, 1941, for twenty thousand members of the Transport Workers Union who were striking to protect their collective bargaining rights, according to a 2010 online article by Peter Dreier. Their appearance at the labor rally was a prelude to the Almanacs’ fabled cross-country, union-hall tour. The tour began in July 1941 at a union hall in Pittsburgh and continued on to California. Seeger told his friend New Jersey banjo player Rik Palieri that Lampell was “the mover” who put together the tour concept and worked out the logistics and performance dates. Lampell even came up with the transportation: a 1932 midnight-blue Buick sedan he obtained from an alleged Paterson gangster. Seeger did most of the driving, and the four Almanacs wrote songs as they traveled between stops, Palieri said, relaying tales of the journey as divulged by Seeger. “These were four guys who were ‘On the Road’ before Jack Kerouac.”

During the hurly burly of American political events in 1941 and the threat of world war on the horizon, the Almanacs received less-than-favorable notoriety for their antiwar album Songs for John Doe, released in May 1941. The recording was retracted when, on June 22, 1941, Germany attacked Communist Russia, breaking a nonaggression pact the two nations had formed in August 1939. Prior to December 7, 1941, there were many political factions—staunch isolationists, conservative Republicans and others—opposed to America’s involvement in the escalating war in Europe. Cray wrote that the Almanacs, in the first months of 1941, “were avowedly activist, anti-war, pro-union and well left of center in their politics. Even if they were not members of the Communist Party, they took their cues from the Daily Worker, Seeger acknowledged. Their songs were topical, polemical and blunt; propaganda set to music.”

As the four Almanacs were preparing for their westward tour, the June 1941 edition of the Atlantic Monthly published an article titled “The Poison in Our System.” It was written by Carl Joachim Friedrich, who was a scholar, lecturer and professor of government at Harvard University. Most of the twelve-page essay dealt with Friedrich’s observations on the turmoil in Europe and efforts to undermine American democracy through propaganda. He made mention of the John Doe album just once, midway through the article:

An outfit which calls itself the Almanac Music Company has recently brought out a series of phonograph records called “Songs for John Doe.” These recordings are distributed under the innocuous appeal: “Sing Out for Peace.” Yet they are strictly subversive and illegal.…They ridicule the American defense effort, democracy and the Army.

Friedrich wrote that “whether Communist or Nazi financed,” the general spirit of the album was indicated by the lyrics of antiwar protest songs such as “C for Conscription” and “Plow Under.” He warned that “unless civic groups and individuals make a determined effort to counteract such appeals, democratic morale will decline.”

Time magazine, in its June 16, 1941 issue, also made a brief mention of the John Doe album in a music review. “Honest U.S. isolationists last week got some help from recorded music that they would rather not have received.…Professionally performed with new words to old folk tunes, John Doe’s singing scrupulously echoed the mendacious Moscow tune: Franklin Roosevelt is leading an unwilling people into a J.P. Morgan war.” The Almanacs returned to the studio and, in February 1942, released the album Dear Mr. President, with songs that supported the U.S. war effort.

Today, the John Doe episode still rankles a vocal segment in American politics. The lingering rub is the notion that, at the time, in order to advance their agendas, leaders in the left-wing progressive movement conveniently turned a blind eye to the brutal dictatorship of Joseph Stalin (1879–1953), secretary general of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Star-Ledger columnist Paul Mulshine expressed his opinion in a January 28, 2014 article:

As I’ve noted, most American conservatives were also anti-interventionist before Pearl Harbor. Like all good lefties, the Almanac Singers were trying to further the interests of Joe Stalin. And Stalin was at that moment in a nonaggression pact with Adolf Hitler. The [John Doe] album was full of songs that lampooned Franklin D. Roosevelt as a warmonger for wanting to help England. Oops! A few days after the album came out, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. The album was quickly recalled and all but a few copies were destroyed. [The Almanacs] immediately cut another album, this time calling on the United States to jump into the war alongside Uncle Joe. The switcheroo worked. The incident was largely lost to history and I have seen little note of it anywhere.

Lampell was drafted in 1943, served in the army air force and eventually dropped out of the music scene. In his profile in the book Tender Comrades , Lampell candidly admitted that he briefly was a member of the U.S. Communist Party in the early 1940s, “toward the end of the Almanac days. The functionaries were obviously delighted to have us out there singing peace songs, then anti-Fascist songs. We believed in what the party was for generally, especially on the home front, but when it came to international events, we didn’t know much about them. I left the party automatically when I was drafted and I never rejoined.”

Millard Lampell with Eleanor Roosevelt (1884–1962), circa 1960. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, Wisconsin.

After being discharged from the army, Lampell remained active in political causes and was drawing attention from right-wing, anti-Communist organizations, such as the Church League of America. These groups monitored his writings and affiliations. Many people in the arts came under similar scrutiny. All of this led to the tribunals in the late 1940s and early 1950s, established by the House Un-American Activities Committee, as well as the McCarthy era of Cold War suspicion and blacklists in the United States.

In the August 21, 1966 op-ed piece for the Sunday New York Times, Lampell revealed how, in 1950, he kept a journal, in which he recorded “the ironic, sometimes bizarre, sometimes ludicrous experience of the twilight world of the blacklist.”

By 1950 I had been a professional writer for eight years, including the time spent as a sergeant in the Air Force that produced my first book, The Long Way Home. I had published poems, songs and short stories, written a novel and adapted it as a motion picture, authored a respectable number of films, radio plays and television dramas, collected various awards and seen my Lincoln cantata, “The Lonesome Train,” premiere on a major network, issued as a record album and produced in nine foreign countries. Then, quietly, mysteriously and almost overnight, the job offers stopped coming.…I began to have increasing difficulty in getting telephone calls through to producers I had known for years. It was about three months before my agent called me in, locked her door and announced in a tragic whisper, “You’re on the list.” What made it all so cryptic was the lack of accusations or charges. Fearing legal suits, the film companies and networks flatly denied that any blacklist existed. Through the next several years, bit by bit, the shadowy workings of the blacklist came into sharp focus.

Lampell survived the blacklist era and in the early 1960s resumed his work as a successful writer, penning the scripts for popular TV programs such as East Side, West Side; The Adams Chronicles; Rich Man, Poor Man; and The Orphan Train. A highpoint in his career came when his screenplay Eagle in a Cage, broadcast on NBC’s Hallmark Hall of Fame, won the 1966 Emmy Award for dramatic writing. The Paterson Evening News, in its May 23, 1966 edition, paid tribute to this son of Paterson: “Lampell created somewhat of a sensation at the generally placid proceedings of the Emmy presentations…by ending his ‘thank you’ for the award with a dramatic declaration: I was blacklisted for ten years. As Lampell walked off the stage…he drew the longest ovation of the night.” Millard Lampell died on October 3, 1997, in Ashburn, Virginia.

THE SEMI –POPULAR FRONT

The international social/political movement known as the Popular Front was a major factor in the cultural divide in the United States during the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. Michael Denning, in his book The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century, explained that the Popular Front, “born out of the social upheavals [of the mid-1930s] and coinciding with the Communist Party’s period of greatest influence in U.S. society, became a radical historical bloc uniting industrial unionists, Communists, independent socialists, community activists, and émigré anti-fascists.” In 1935, the seventh congress of the Comintern (Communist International) endorsed a “popular front” against the rising fascist powers in Europe.

Denning pointed out:

The latter-day success of the folk music revival—the music of Woody Guthrie, Huddie Ledbetter [Lead Belly] and Pete Seeger—has often led historians and cultural critics to assume that folk music was the soundtrack of the Popular Front. This is not true. The music of the young factory and office workers, who made up the social movement, was overwhelmingly jazz. The emergence of jazz as a mass commercial success…not only coincides with the beginning of the Popular Front, but it was in large part a sign of the cultural enfranchisement of the second-generation children of migrants from the Black Belt South and from Jewish, Italian and Slavic Europe.

Daniel Sidorick, a lecturer in the Labor Studies Department of Rutgers University, said that folk revival music had connections to the labor movement segment of the Popular Front primarily because performers aligned themselves with striking workers on the picket line. Sidorick also stressed that the Popular Front movement in the United States was diverse and not monolithic; its members came from a wide spectrum of political viewpoints. “They worked together, nonetheless, on many political and cultural activities, though occasionally with some friction when particular agendas went in different directions and conflicted,” he said. American musicians, actors, artists and writers floated in and out of the political circles associated with the Popular Front.

Sidorick said the Popular Front movement began to unravel during the anti-radical hysteria associated with McCarthyism in the early 1950s, which included the blacklisting of writers and performers, as well as the firing of Rutgers professors “for not adhering to the dominant political orthodoxy of the time.” In December 1994, Rutgers compiled an internal report (Academic Freedom Cases, 1942–1958) on the dismissal of the professors.

THE VOICE

Paul Robeson, the legendary singer, scholar, actor and international political and social activist and a member of Rutgers’ graduating class of 1919, returned to his alma mater for a concert at the Rutgers gymnasium on January 8, 1947. “Paul Robeson Music Warmly Received Here” was the headline on page one of the January 10, 1947 student newspaper, the Daily Targum. The newspaper reported that a capacity crowd was mesmerized by his powerful baritone/bass voice during the two-and-a-half-hour performance. This was a world-class artist at the height of his powers, and he generously acknowledged the appreciative audience with fifteen encores, including his signature tunes “Water Boy” and “Ol’ Man River.” Pianist Lawrence Brown accompanied Robeson and also harmonized with him on several spirituals.

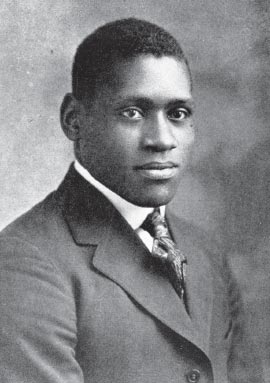

Paul Robeson, a 1919 Rutgers graduate. Courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, New Brunswick.

“Mr. Robeson sang a varied program of songs in a half-dozen different languages, each of which received a purity of enunciation,” the article stated. “Songs ranging from a seventeenth century English air, through German, Italian, French, Hebrew and Russian selections, were offered with telling effectiveness. The fascinating stage personality of Mr. Robeson was indeed refreshing. The wonderful spontaneity and color of his voice was heard throughout the evening.”

In an interview that also ran on the front page of the January 10, 1947 Targum, Robeson told reporter Norman Ledgin that Rutgers students “have a lot of hard work ahead of them. When I was in my last year here, [World War I] had just ended and we had many of the same problems that you’re faced with today. New developments like atomic energy came out of this war and it’s mainly the engineering and science students who will have to cope with them in the near future. A lot of sound judgment is going to have to enter diplomatic circles, too.” Later that same year, on September 18, 1947, Robeson gave a benefit concert at Plainfield High School, as reported by the Daily Home News.

The diverse set list for his 1947 Rutgers concert demonstrated Robeson’s respect for the value of folk music. Two years after the Rutgers concert, he proclaimed his high regard for ethnic folk music in an interview published by Sovietskaia Muzyka (Soviet Music) that was reprinted in the 1978 book Paul Robeson Speaks; Writings Speeches Interviews 1918–1974:

There is an old Spanish proverb that goes: sing me your folk songs and I’ll tell you about the character, customs and history of your people. How true! Folk songs are, in fact, a poetic expression of a people’s innermost nature, of the distinctive and multifaceted conditions of its life and culture, of the sublime wisdom that reflects that people’s great historical journey and experience.

I don’t think I have to go into a detailed appraisal here of the great artistic merit of Negro folk music or of its unquestionable significance for all of mankind. This is universally acknowledged. Even in capitalist America, where there exists racial discrimination of revolting proportions, where many “cultured” whites refuse to recognize the Negro as a human being—even there our folk songs constitute, as strange as it may seem, an object of national pride for many Americans. These songs are striking in the noble beauty of their melodies, in the expressiveness and resourcefulness of their intonations, in the startling variety of their rhythms, in the sonority of their harmonies, and in the unusual distinctiveness and poetic nature of their forms.

Martin Bauml Duberman, in his book Paul Robeson: A Biography, wrote that Robeson, born in Princeton on April 9, 1898, began his singing career by utilizing connections with members of the Harlem Renaissance movement. Robeson landed a recital date on April 19, 1925, a program of spirituals, accompanied by Lawrence Brown, at the Provincetown Playhouse in New York’s Greenwich Village. “In stressing art as a solvent for racism, Robeson was articulating a characteristic position of the Harlem Renaissance intellectuals: racial advance would come primarily through individual achievement,” Duberman wrote. As a result of his performance at the Provincetown Playhouse, Robeson signed a contract to record with Victor. His Victor sessions in Camden began on July 16, 1925, and continued throughout that month, with additional sessions in January 1926, according to the Discography of American Historical Recordings. At the Victor studios, Robeson and pianist Brown recorded spirituals, such as “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord,” “Water Boy,” “Steal Away,” “Joshua Fit de Battle ob Jerico,” “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “Motherless Child.” These recordings, in turn, led to concert bookings in Europe and the United States. The duo also recorded music at Victor’s New York studios at later dates.

Duberman quoted Robeson, who said that folk songs were “the music of basic realities, the spontaneous expression by the people for the people of elemental emotions.” Duberman explained that Robeson felt folk songs of the Russian, Hebrew, Slavonic, Highland and Hebridean people “held the deepest affinity with the underlying spirit of Afro-American songs.”

On June 3, 1941, Robeson opened the season for the Essex County Symphony Society as a soloist, performing with conductor Dr. Frank Black and the Eva Jessye Choir. The evening concert, billed as an “All-American program,” was held outdoors at City Schools Stadium, located at the intersection of Roseville and Bloomfield Avenues in Newark. The June 4, 1941 edition of the Newark Evening News covered the event, reporting that an audience of over twenty thousand people enjoyed the show. “Much of the success of the occasion was due to Paul Robeson, the featured soloist. His deep, rich tones rolled over the field and into the stands with a telling effect rarely achieved by any other stadium soloists” (this was the sixth season of the Essex County Symphony Society’s outdoor concert series).

The article said the “high spot” of the evening was “Ballad for Americans,” a signature Robeson tune written in 1939 by John La Touche and Earl Robinson. “The expansive scope of the work seemed to fit the outdoor conditions unusually well,” the story stated. “Its potent mingling of drama and comedy was voiced by Robeson with a clear diction that made it understandable to all.” Though not a folk song, the composition does address grass-roots, “everyman” values of America’s cultural diversity. The lyrics are an affirmation that people of all ethnicities, religions and racial backgrounds are members of the American family; that the country’s future remains bright, and the nation’s best songs have yet to be sung.

Robeson sang folk songs and spirituals during years of international concert tours, and he performed twelve concerts and recitals at Carnegie Hall, New York—the first on November 5, 1929, and the last on May 23, 1958, according to information posted on the Carnegie Hall website. In addition, Carnegie Hall staged a memorial tribute to Robeson on October 18, 1976, which included a performance by Pete Seeger. Outside of Robeson’s music career, publications and pundits frequently critiqued him for his fight against racism, his support for world peace and human rights and his alleged membership in the Communist Party. Paul Robeson died in Philadelphia on January 23, 1976. His obituary appeared on page one of the January 24, 1976 edition of the New York Times. “One of the most influential performers and political figures to emerge from black America, Mr. Robeson was under a cloud in his native land during the Cold War as a political dissenter and an outspoken admirer of the Soviet Union,” the Times obituary reported.

IMPROPER QUESTIONS FOR ANY AMERICAN TO BE ASKED

The New York Times reported on April 5, 1961, that forty-two-year-old Pete Seeger was sentenced by a New York federal court to one year in prison for refusing to provide information to the House Un-American Activities Committee. The charge, filed in July 1956, was “contempt of Congress.” Seeger, accompanied by his counsel Paul L. Ross, had appeared before the committee on August 18, 1955, and declined to answer questions concerning his alleged involvement in the Communist Party. However, Seeger prevailed in the case, with his sentence overturned by the U.S. Court of Appeals on May 18, 1962.

During his 1955 testimony, Seeger sparred with House committee chairman Francis E. Walter and staff member Frank S. Tavenner Jr. (an online version of the testimony transcript is posted by Harvard College Library, “Investigation of Communist Activities, New York Area, Part VII”). The heated exchange focused on an appearance by Seeger during a 1948 May Day rally in Newark. The dialogue between Seeger and Tavenner began with Seeger answering questions about his service in the armed forces during World War II. Seeger was drafted into the army in July 1942 and was discharged in December 1945. Tavenner then introduced “Seeger Exhibit No. 1” to the committee. This exhibit was a photo copy of the April 30, 1948 issue of the Daily Worker, which printed an advertisement of a “May Day Rally: For Peace, Security and Democracy. Are you in a fighting mood? Then attend the May Day rally.” The advertisement stated that the event, which was held on April 30 at the Graham Auditorium in the Prince Hall Masonic Temple on Belmont Avenue in Newark, would include “entertainment by Pete Seeger.” Tavenner pointed out that the ad said the rally was being held under the auspices of the Essex County Communist Party.

Seeger was asked directly to confirm whether he had lent his talent to “the Essex County Communist Party on the occasion indicated by this article from The Daily Worker.” Seeger declined to respond. When pressed by Chairman Walter, Seeger again refused to answer the question directly or provide details. Walter again asked him: “What is your answer?” After consulting with Ross, Seeger addressed the House committee members:

I feel that in my whole life I have never done anything of any conspiratorial nature and I resent very much and very deeply the implication of being called before this committee that in some way because my opinions may be different from yours…I am any less of an American than anybody else. I love my country very deeply, sir. I have sung for Americans of every political persuasion, and I am proud that I never refuse to sing to an audience, no matter what religion or color of their skin, or situation of life. I am not going to answer any questions as to my associations, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election, or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this.

Many sources indicate that, from 1942 to 1949, Seeger was a member of the Communist Party. In the book Pete Seeger: In His Own Words, edited by Rob Rosenthal and Sam Rosenthal, a collection of writings by and about Seeger, he said he dropped out of Harvard University in 1938. “Got too interested in politics. Let my marks slip. Lost my scholarship. In the winter of 1939 I was a member of a young artists group in New York City. It was a branch of the Young Communists League.” This also was the period when he worked with Alan Lomax at the Archive of the American Folk Song at the Library of Congress, a connection that led to his meeting Woody Guthrie at the Grapes of Wrath concert.

Amid the blacklisting controversies of the 1950s, Seeger emerged as a champion of folk revival music. He continued to record studio albums and receive concert bookings. On June 16, 1963, he appeared at the Music Circus in Lambertville. Twelve-year-old Peter Stone Brown and his dad, Joe, who was a devoted Seeger fan, were in the audience that day. Brown, in a blog post from April 25, 2012, wrote that this was the third time he had attended a Seeger show. Even at this early age, Brown knew there was “something different” about the Lambertville concert. “Seeger was singing new material from young musicians like Bob Dylan and Tom Paxton,” Brown said during a September 2015 phone interview. “You knew there was something going on in the lyrics of these songs. The words were very political.”

Brown recalled that two tunes sung by Seeger at the Lambertville concert—Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and “Who Killed Davey Moore”—were especially thought provoking. In an April 27, 2012 blog post, Brown wrote that, at the end of Seeger’s rendition of “Hard Rain,” “my dad turned to me and asked: ‘Do you know what that [song] was about?’ ‘The bomb,’ I replied [meaning the atom bomb], but it was a question. I didn’t know it at the time, but those two songs were the beginning of something that was going to change my life.” Brown, who resided in Millburn during the 1960s and 1970s, went on to become a writer and touring performer of Americana roots music.

Created by actor and impresario St. John Terrell (1917–1998), Lambertville’s Music Circus was an outdoor theater-in-the-round under a circus-like tent with over two thousand seats. It was located on old U.S. Route 202 and provided an assortment of entertainment from 1949 to 1970, according to the website “St. John Terrell’s Music Circus.”

HOOTENANNY

As detected by Brown’s perceptive young ears during Seeger’s Music Circus performance, a new wave of folk revival music was on the horizon. In the early 1960s, this music demonstrated its commercial viability, especially among college students. The American Broadcasting Company (ABC) picked up on this trend and unveiled an innovative TV program called Hootenanny, which presented selections of live music concerts at college campuses from the most popular folk revival bands and performers of this period. The show first aired on April 6, 1963. The New York Times, in its April 8, 1963 edition, reviewed Hootenanny, praising it as “a thoroughly pleasant and enterprising departure from the staid programming norm. Mark it down as the hit of the spring.” The Times article also mentioned “one disquieting note”: the conspicuous absence of Pete Seeger, who, during his career, had served as an inspiration and role model for many of the artists on the show. “Apparently, Pete Seeger’s private political concerns continue to keep him off all network shows of folk singers,” the article stated. “Since he is at complete liberty to appear on stages and can be heard at home on recordings, why should TV prolong its blacklist?” Even though he won his legal battle with the House Un-American Activities Committee, Seeger still was considered a pariah by network television.

This “prolonged blacklisting” drama played out on the campus of Rutgers University, which was selected to be the site for the Hootenanny concert taping on Monday, April 15, 1963. The show was staged at the Ledge, the student center on the New Brunswick campus. The program’s air date was April 27, 1963—the fourth installment of the first season, which included music by the Chad Mitchell Trio, the Smothers Brothers, Judy Henske and the Simon Sisters (Carly and Lucy), according to archival material posted on the blog for the Hootenanny TV show.

The Daily Targum, in its April 15, 1963 edition, ran a story at the top of page one: “Picket to Protest Seeger Blacklisting.” The article’s lead paragraph stated that “an ad hoc committee of students will picket the ABC Hootenanny tonight because Pete Seeger was not invited to participate in the television series.” The Associated Press, in an April 15, 1963 wire story report, indicated that four hundred “singing, sign-carrying students” protested the concert outside of the Ledge while inside there was an audience of six hundred students. The lead story on the front page of the April 16, 1963 edition of the Targum reported the protest was peaceful as Rutgers students camped outside of the Ledge for nearly two hours.

But that night there was a counter demonstration. Students carried American flags and led a cheer of “G-O-L-D-W-A-T-E-R,” a reference to Barry Goldwater, the U.S. senator from Arizona and conservative Republican candidate in the 1964 presidential election. The two demonstrations that night outside the Ledge were an early sign of the polarized, right-wing/left-wing, conservative/liberal ideologies that would take shape in American politics during the 1960s. A member of the student council who led the Goldwater rally submitted a letter to the editor, which the Targum ran in its April 18 edition:

My leading the Goldwater cheer was in protest against the picket. The purpose of the anti-picket demonstration was to affirm the right of the American Broadcasting Company and Hootenanny to exercise their constitutional prerogatives of freedom of choice and freedom of association in their employee policies. Contrary to the anti-ABC pickets, the right of free speech is not abridged when ABC does not hire Pete Seeger.…The First Amendment prohibits the Congress from passing a law abridging freedom of speech, but it does not prohibit me to refuse to allow Seeger to sing in my home; likewise, [ABC] may decline to employ Seeger.

The jousting continued between Seeger and the TV networks. The Times, in a September 9, 1963 story, reported that Seeger had refused to sign a “loyalty oath” in order be considered for an appearance on Hootenanny. ABC also required him to furnish “a sworn affidavit as to his past and present affiliations.” When Seeger refused, ABC said “the singer would not be considered for an appearance.” Some musicians supported Seeger and boycotted the show. ABC canceled Hootenanny after two seasons.

ULTRA -HIGH FREQUENCY

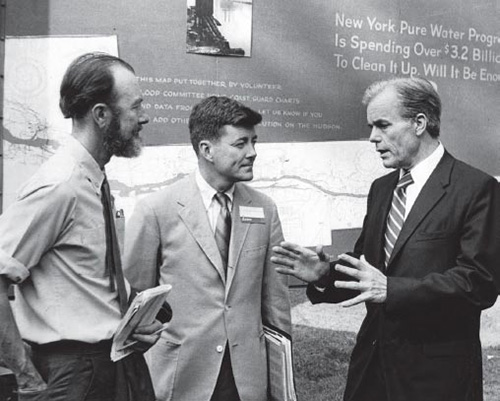

Seeger no doubt had an appreciation for television’s reach as a powerful medium to connect with an audience. Spurned by the three major TV networks, Seeger opened a new door: ultra-high frequency (UHF). A technology that dates back to the early 1950s, UHF went beyond the regular television dial (two to thirteen) to provide specialty, regional programming. It was a pioneering field of broadcasting that confronted a host of financial and technical difficulties, such as a constant search for adequate private funding and poor broadcast signal quality. Most TV sets needed to be fitted with special equipment, a tuner and an antenna, in order to receive the signal. One UHF venture in the New Jersey/New York TV market was station WNJU. The website www.wnjutv47.com , established for the station’s alumni, posted that in April 1964 “the darkened studios of the old Channel 13, located in the upper floors of the Mosque Theater in Newark, New Jersey, came alive as the brand new WNJU-TV.” (The theater today is known as Newark’s Symphony Hall.)

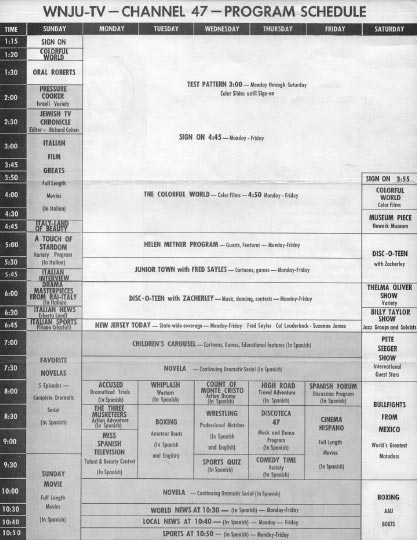

Joe LoRe, a 1963 graduate of Bayonne High School who maintains the WNJU alumni website and works to preserve the memories of the old UHF station, said that, as a young man, he jumped at the opportunity to become involved in the effort. “It was an innovative atmosphere at the station, to say the least,” LoRe said. “It was all new. We had big challenges. It was an uphill battle.” He said the station was also known as Telemundo 47, a nod to the region’s large Latin American population. Programs included professional wrestling, amateur boxing bouts, bullfights from Mexico, a jazz show with pianist Billy Taylor, Spanish-language movies and a live dance show known as Disc-O-Teen, hosted by the inimitable TV and radio personality John Zacherle.

An original WNJU-TV Channel 47 program schedule. The Pete Seeger Show is listed at the far right, in the Saturday, 7:00 p.m. time slot. Courtesy of Joe LoRe.

Interviewed on the Public Broadcasting TV series American Masters, Seeger confirmed that the inspiration for doing a TV show in Newark came about because he was banned from network television. LoRe said that, most likely, Ed Cooperstein, WNJU’s general manager, reached out to Sholom Rubinstein, Seeger’s manager, with the idea of doing a show that would feature live folk and folk revival music with special guests. The project moved forward, produced and funded by Seeger, Rubinstein and Seeger’s wife, Toshi Seeger, and on Saturday, November 13, 1965, at 7:00 p.m., Rainbow Quest, also known as the Pete Seeger Show, made its broadcast debut. An article in the November 15, 1965 edition of the New York Times, “TV: Pete Seeger Makes Belated Debut,” took note of the event:

A night of television extremes took place Saturday evening over television station WNJU-TV in Newark. There was taped bullfighting from Mexico as the newest attraction for the family viewing group. More importantly, there was the long overdue TV debut of Pete Seeger, the folk singer, in a program that should stand as one of the gems of the local video scene. Channel 47’s coup in obtaining the services of Mr. Seeger is reason enough to make sure that one’s set can pick up UHF. The man who has played such a vital role in stimulating appreciation of folk music has a full 60 minutes to call his own. Characteristically, his premiere was blissfully free of the slightest trace of show business orientation. The hour with Mr. Seeger and his friends—the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem and Tom Paxton—was spent singing and playing around a plain wooden table. Theirs was the art of folk music as it has never really been seen on the big, rich television channels—performed for the sheer joy of doing it and rich in warm genuineness and sincerity. After all the aberrations of folk music on the networks, Channel 47 alone has the honest article.

Taped in black and white, the first program began with Seeger standing, playing solo banjo and singing the song “Oh, Had I a Golden Thread.” He then addressed the viewers directly. “You know, I’m like a blind man, looking out through this little magic screen, and I don’t know if you can see me. I know I can’t see you. But all the same, tonight and in weeks to come I’d like to invite you to come with me on a Rainbow Quest, to try and seek out all the different colors and kinds of human beings we have in our land.”

The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem were Seeger’s first guests, and they sang “The Little Beggar Man.” They performed other tunes and enjoyed an engaging, informal banter with Seeger. Next, Seeger introduced “this young fellow over here,” Greenwich Village bard Tom Paxton. Paxton told Seeger he had just written a brand-new song, “about an event that happened just the other night.” Paxton was referring to the great metropolitan area blackout that occurred on Tuesday, November 9, 1965. A smiling Paxton, playing his guitar, began singing his topical, humorous composition, imagining what sort of mischief people were doing to entertain themselves during the infamous power outage.

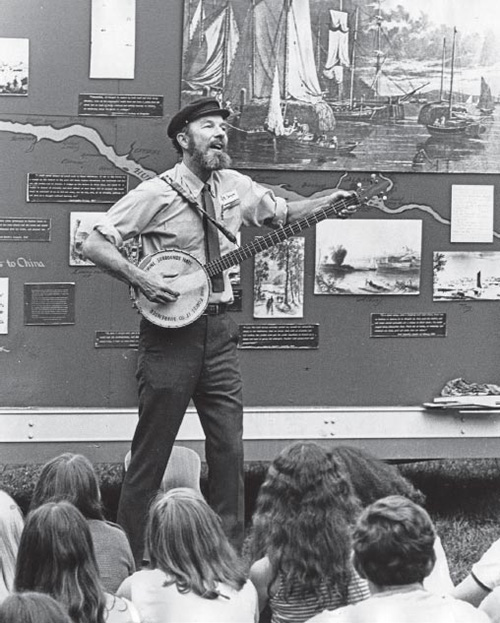

Working as a camera man, LoRe had a front-row seat for the Seeger show and took part in the production work. “Pete Seeger was a sweetheart,” LoRe recalled. “He was laid back, polite and very easy to work with. He didn’t have a big ego like lots of other TV stars.” LoRe said he worked on five or six of the Rainbow Quest programs, saying the show had no rehearsals and was “taped live.” The show was shot with three RCA black-and-white TK-60 cameras and recorded on Quadra-Flex, two-inch video tape. He noted that, because the producers funded the production work and owned the tapes, many of the Rainbow Quest episodes survive and can be seen online or purchased as CDs from retail outlets. Looking back, LoRe marveled at the guests Seeger was able to attract to the program—obscure and well-established artists—people like Judy Collins, Johnny Cash, Reverend Gary Davis, Doc Watson, Donovan, Mississippi John Hurt and Roscoe Holcomb. They all performed with Seeger in the Newark studio, and their music reached New Jersey viewers. Thirty-nine shows were recorded and broadcast between 1965 and 1966. In subsequent years, the shows were repeated on Public Television stations.

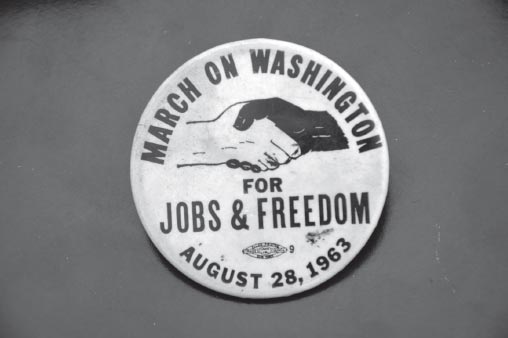

Seeger offered his own critique of the Rainbow Quest show in an April 1968 letter to Bert Snow, the director of public relations at the public television station KCET in Los Angeles. The letter, marked “found in Seeger files,” is part of the collection of material in the book Pete Seeger: In His Own Words. Written in a question-and-answer format, the letter was Seeger’s brief feedback to specific inquiries posed by Snow. Seeger wrote that the Rainbow Quest series “reflects one man’s curiosity about different kinds of people and their music, either old or new. That’s why only a few of the performers are well known. The Rainbow Quest gives me a chance to swap songs with many different kinds of performers. And remember, the same songs can mean different things to different people. This is fun to explore.”