Chapter 20

3 John 1–4

Literary Context

These verses form the conventional Greco-Roman letter opening in a manner that makes 3 John more similar to ancient secular letters than any other book of the NT. The address of a letter was always the first line of a letter, identifying both the writer and the recipient. The writer of 3 John identifies himself only as “the elder” and writes to a dear acquaintance whose name is Gaius. Knowing that this book originated as personal correspondence provides a key to interpreting its message because we can be assured that the issues it addresses and the names it mentions refer to authentic people and that the given situation was real.

Unlike poetry or apocalyptic literature, this note gives no indication that the author wishes his writing to be understood symbolically or allegorically. There is no reason to believe that the situation depicted here is anything but actually true at the time the note was written. Because we lack sufficient historical background to know with certainty who and where the elder was and more precisely who Gaius was, where he lived, or what were the specifics of the situation that gave rise to this letter, such historical background must be reconstructed largely by inference from the letter itself. Any such reconstruction must necessarily be held with the exegetical humility of acknowledged uncertainty. Nevertheless, while we don’t know everything we might wish we knew about the origin of 3 John, we do know enough to understand the significance of its message for Christians in other times and other places.

As rhetorical analysis indicates, these opening verses (vv. 1–4) comprise the exordium, which introduces the main topic of the discourse and prepares Gaius to be receptive for what follows in the letter. Specifically, the elder focuses on Gaius by praising his faithfulness to following the truth, as exemplified by his previous practice of Christian hospitality.

- I. The Letter’s Address and Greeting (vv. 1–4)

- A. The Address of the Letter (v. 1)

- B. A Wish for Well-Being (v. 2)

- C. Basis of the Elder’s Confidence (v. 3)

- D. Implicit Exhortation (v. 4)

- II. The Reason for Writing (vv. 5–8)

- III. The Problem with Diotrephes (vv. 9–11)

- IV. Introducing Demetrius (v. 12)

- V. Closing (vv. 13–15)

Main Idea

The opening verses of this letter introduce its major concern, “the truth” (ἡ ἀλήθεια), which is mentioned four times in the first four verses. The elder finds no greater joy than hearing from others that his spiritual children are living faithfully in the truth of the gospel, which takes the topic of truth out of the abstract and makes it intensely personal.

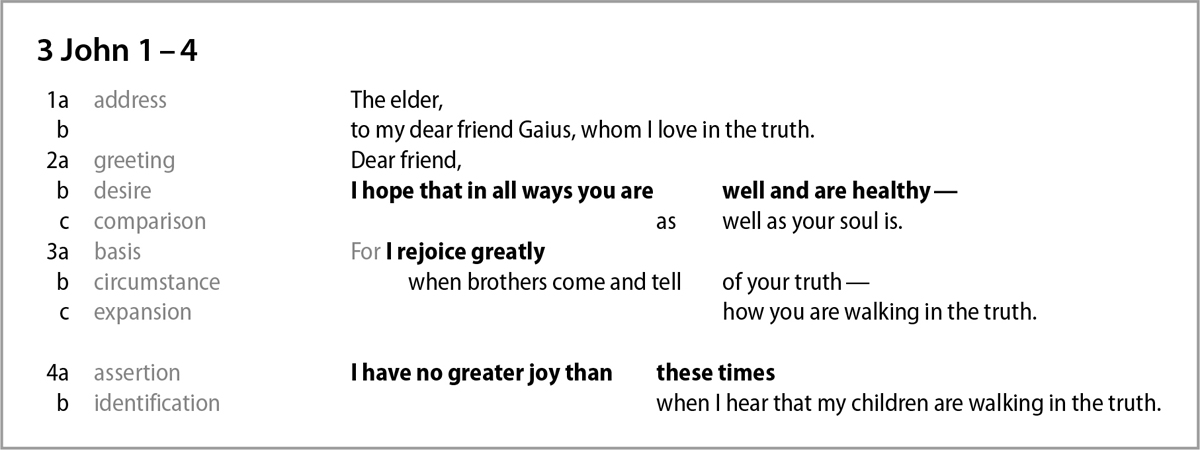

Translation

Structure

As noted under Literary Context, these opening verses exhibit the standard Hellenistic letter opening. The author identifies himself only as “the elder” (ὁ πρεσβύτερος) and the recipient as Gaius. The standard address is amplified with a term of affection for Gaius, which indicates the apparently warm personal acquaintance between him and the elder. The conventional wish for health that is typical in Hellenistic letters is personalized by the elder’s knowledge based on good reports he has heard that Gaius is spiritually healthy.1

Though couched in the form of a Hellenistic letter greeting, the elder reminds Gaius that his faithfulness to the truth is bringing great joy to the elder and serves as a gentle and implicit exhortation that Gaius will continue to bring the elder joy by remaining faithful to the truth.

Exegetical Outline

- I. The Letter’s Address and Greeting (vv. 1–4)

- A. The address of the letter (v. 1)

- B. A wish for well-being (v. 2)

- C. Basis of the elder’s confidence (v. 3)

- D. Implicit exhortation (v. 4)

Explanation of the Text

1 The elder, to my dear friend Gaius, whom I love in the truth (Ὁ πρεσβύτερος Γαΐῳ τῷ ἀγαπητῷ, ὃν ἐγὼ ἀγαπῶ ἐν ἀληθείᾳ). In this standard form of Hellenistic letters, the writer identifies himself with a word in the nominative case and the name of the person to whom he is writing in the dative case.

Although the Greek term “elder” (πρεσβύτερος) can be used in a general sense to refer to an older man in his senior years, in the NT the term most often refers to an office of oversight in the local church.2 Because the structure of first-century Greco-Roman society held a special place for the patriarch of a family (the pater familias), the leader of an assembly might typically have been an older man, collapsing the distinction between the two senses of the word “elder.”

In the case of the early church, local groups of believers typically met in a home whose owner may or may not have been the spiritual overseer of the church but who was obviously influential in the life of the congregation. The tone and content of 3 John show that the elder was a spiritual leader whose authority extended beyond one local house church, for he evidently felt free to exhort Gaius and seems confident that his words will be well received, even though Gaius is clearly not a member of the elder’s local home church. Furthermore, the fact that the author of this letter refers to himself only as “the elder” without specifying his name implies that Gaius knows his identity. It also suggests that the letter is to be read as more than a note between friends; it comes with some ecclesial authority, an authority that Gaius is expected to recognize.

Some interpreters argue against apostolic authorship by taking the author to be one of the presbyters whom Papias calls the bearers and transmitters of the apostolic tradition (see Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 3.39.3), though it is debatable whether or not his categorization would exclude an apostle.3 Moreover, the word “elder” (πρεσβύτερος) had been widely used over a long period of time to refer to the leader of an assembly, first by Jewish writers and later by Christian writers, and therefore it cannot be used as evidence that the letter dates to after the lifetime of the apostles when a certain form of ecclesial hierarchy emerged with a more clearly defined office of elder. The author’s self-designation as “the elder” is also found in 2 John 1, and both letters have similar closings (2 John 12; cf. 3 John 13). Taken together with the similar style, vocabulary, and themes of the letters, this letter strongly suggests that both came from the same person. (See the discussion of authorship in the Introduction to 1, 2, and 3 John.)

Unless Gaius can be identified with other men of the same name mentioned in the NT, nothing is known of him except what can be inferred from this letter. He is a Christian man considered by the elder to be true to the faith (vv. 3–4), who was personally known by the elder, who was apt to offer hospitality of a substantial nature (vv. 5–8), who was widely respected (v. 3), and who exercised a degree of influence in the church (vv. 2, 5, 6a). The personal nature of Gaius’s relationship to the elder is attested by the remark that the elder has much more on his mind as he writes and hopes to visit Gaius soon (vv. 13–14).

The warm tone of this note is set when the elder places “to my dear friend Gaius” (Γαΐῳ τῷ ἀγαπητῷ) in the address of the letter. Various forms of the verb for “love” (ἀγαπάω) or its cognates are used by the apostle Paul (Rom 12:19; 1 Cor 10:14; 15:58; 2 Cor 7:1; 12:19; Phil 2:12; 4:1), James (Jas 1:16, 19; 2:5), Peter (1 Pet 2:11; 4:8, 12; 2 Pet 3:1, 8, 14, 17), Jude (Jude 3, 17, 20), and the author of Hebrews (Heb 6:9) to describe their relationship to the Christian recipients of their letters. But forms of the verb “to love” are especially frequent in the letters of John (1 John 2:7; 3:2, 21; 4:1, 7, 11; 3 John 2, 5, 11).

Given the widespread use of this term by several Christian authors in reference to so many fellow Christians, it appears to be a conventional Christian term (though nonetheless sincere) and cannot be used here to speculate on the distinctive nature of the elder’s relationship with Gaius. Forms of ἀγαπάω are found centuries later in the opening address of letters between Christians, often alongside a form of “brother” (ἀδελφός), which indicates that the apostolic correspondence found in the NT shaped subsequent Christian letter writing.4

The verb for “love” (ἀγαπάω) is adverbially modified by the prepositional phrase to specify a love that is “in the truth” (ἐν ἀληθείᾳ). It is syntactically identical to the phrase in the relative clause in 2 John 1, addressed to “the chosen lady and her children, whom I love in the truth” (οὓς ἐγὼ ἀγαπῶ ἐν ἀληθείᾳ). Note the emphatic use of the personal pronoun “I” (ἐγώ) and the anarthrous noun for “truth” in the phrase in both letters.

If this were the only reference to “truth” in 3 John or in the Johannine corpus, Bultmann would probably be right that it should be read as synonymous with the adverb “truly” (ἀληθῶς), meaning “in reality, authentically.”5 In that case it would refer simply to the sincerity of the elder’s love. But in Johannine thought, love is closely associated with truth defined as the revelation of God, for God’s revelation in Christ reveals God’s love for those he came to save (see “In Depth: ‘Truth’ in John’s Letters” at 1 John 1:6). On that basis those whom Christ has saved are taught to love one another as God loves them (cf. 1 John 4:11). This expression of love for Gaius in the opening salutation of 3 John refers to their shared faith in Christ as the basis of their relationship, and the elder’s hope that it will continue undisrupted.

Gaius is addressed three more times with the vocative of “dear friend” (ἀγαπητέ; vv. 2, 5, 11), emphasizing the bond of Christian fellowship between him and the elder. In the context of conflict within the Johannine community, the emphatic pronoun “I” (ἐγώ) here in v. 1c (also in 2 John 1) signals the elder’s continuing regard for Gaius, perhaps in contrast to how other Christians of influence, such as Diotrephes, might view Gaius in light of his hospitality to those sent by the elder. This repetition of “dear friend” and the emphatic “I” reinforce the elder’s relationship with Gaius, since the elder is about to ask Gaius to do what would undoubtedly put him into tension, if not outright hostility, with Diotrephes and his followers.

2 Dear friend, I hope that in all ways you are well and healthy—as well as your soul is (Ἀγαπητέ, περὶ πάντων εὔχομαί σε εὐοδοῦσθαι καὶ ὑγιαίνειν, καθὼς εὐοδοῦταί σου ἡ ψυχή). The affection the elder has for Gaius is repeated as he addresses him with the vocative adjective translated “dear friend” (Ἀγαπητέ). The wish for health was a standard part of the Hellenistic letter, found frequently in the conventional form, “Above all I pray that you are healthy” (πρὸ πάντων εὔχομαί σε ὑγιαίνειν), but among NT letters it occurs only here, although with the preposition “about” (περί) instead of “before” (πρό; see below).9 The earliest extant appearance of the phrase is in a letter that dates from about AD 25, where it is placed at the end, and it continued to be used in letters throughout the second and third centuries.10

Because the verb “I pray” (εὔχομαι) is part of the conventional phrase, it should not be pressed for a more specific Christian or theological meaning. Its use is similar to the English “good-bye,” which virtually every English speaker uses without knowing that it is a contraction of the phrase “God be with you.” Just as it would be a misunderstanding to think that everyone who says “good-bye” is pronouncing a blessing, it is probably wrong to overload “I pray” with meaning here, even though the same term was used in the some contexts to refer to praying to a deity. Nevertheless, one cannot argue that because a Christian English speaker uses the parting phrase “good-bye” with no thought of its original meaning, he or she would be disinclined to so bless a friend. Similarly, the fact that “I pray” cannot be pressed does not mean that the elder did not or would not pray for Gaius. But that isn’t strongly in view here. Given the idiomatic nature of the expression, prayer should not be made the main exegetical point of the passage.11

Similarly, the fact that the health wish was part of an epistolary convention also means that “I pray you … are well” (εὔχομαί σε … ὑγιαίνειν) should not be taken to mean that Gaius was ill or weak, as some interpreters have previously done.12 Nor should it be spiritualized as a prayer specifically for spiritual health, as Carrie Judd Montgomery did at the turn of the twentieth century.13 Such examples show how biblical interpretation can go awry when texts are not understood within their original linguistic and cultural context.

Third John 2 differs from the conventional phrase in the choice of a different preposition (περί instead of πρό), expressing the sense “concerning all things,” or in more idiomatic English, “in every way.” The Greek text is stable here, and there are no textual variants to support a conjectural emendation to “above all” (πρό), which have been proposed from time to time.14 Even if there were textual variants, the reading “concerning/in” (περί) is the more difficult reading, which scribes would likely change to conform with the standard form; thus, “concerning/in” should be accepted as original. More conclusively, another first-century letter from Arsinoites, Egypt (BGU 3 885) contains almost the exact phrasing, “In all ways I pray you …” (περὶ πάντων εὔχομαί σε), including the preposition “concerning/in” (περί).15

Some English versions translate the other infinitive as “prosper” (εὐοδοῦσθαι; e.g., NKJV, NASB), leading some readers to think of material wealth. The “health and wealth gospel” assures 3 John a place in the modern history of interpretation. One morning Oral Roberts opened the Bible for a word from God and read the first verse his eyes fell upon, which happened to be 3 John 2. He took this verse to be a prompting of the Spirit to begin a ministry of “whole-person prosperity.”16 Over time this verse became what Roberts called the “master key” of his ministry, for he read it to say, despite the Greek, that God desires above all things that Christians have the fullness of prosperity here and now, an interpretation that corrected his previous view of the virtue of Christian poverty. Kenneth Hagin followed Oral Roberts in using 3 John 2 as a direct promise from God to all Christians.17

Against this interpretation, a study of the Greek verb “to prosper,” which occurs again immediately in v. 2 in reference to the soul (also in Rom 1:10 and 1 Cor 16:2), confirms what Albert Barnes wrote about this word in the mid-nineteenth century: it “seems to refer to the journey or passage of life” and could refer “to any plan or purpose entertained,” not just material wealth.18 Of course, to enjoy favorable financial circumstances is not excluded from the elder’s wish “concerning all things” (περὶ πάντων) for Gaius, and “prosper” is used in the context of finances in 1 Cor 16:2a.

The wish for health and good circumstances in everything is compared to the good state of Gaius’s spiritual health (“as well as your soul is”; καθὼς εὐοδοῦταί σου ἡ ψυχή), which the elder knows because others have testified that Gaius is faithful to the truth and continues to live by it (v. 3). The ancient interpreter Oecumenius comments that Gaius is doing well because he is living according to the truth of the gospel.19 However, spiritual health does not necessarily imply well-being in every circumstance of life. Especially in the first century, fidelity to Christian faith could in fact result in various forms of suffering, persecution, and even execution (cf. 1 Pet 2:21). The elder knows that Gaius is doing well spiritually because those to whom he previously extended hospitality have returned and given a good report about him. Because the elder is going to ask Gaius to continue to express his faithfulness to the truth by continuing to receive the elder’s envoys, the elder alludes here to Gaius’s past faithfulness in this regard. With this, the letter transitions to material that will form the background of the elder’s request in v. 6.

Unlike the apostle Paul’s letter openings, this one contains no prayer or wish for “grace,” “mercy,” or “peace,” though the elder does send a wish for peace in the closing (v. 15a).

3 For I rejoice greatly when brothers come and tell of your truth—how you are walking in the truth (ἐχάρην γὰρ λίαν ἐρχομένων ἀδελφῶν καὶ μαρτυρούντων σου τῇ ἀληθείᾳ, καθὼς σὺ ἐν ἀληθείᾳ περιπατεῖς). The elder knows that Gaius is spiritually well (v. 2) because some “brothers” have come to the elder and have testified that Gaius is “walking in the truth” (καθὼς σὺ ἐν ἀληθείᾳ περιπατεῖς). The English equivalent of “just as” (καθώς), learned in first-year Greek, will not serve well here. This adverb should be construed as either “the extent to which” or “because.”20 The frequently occurring noun “truth” (ἀλήθεια) is found in the Johannine writings in both anarthrous and articular constructions without distinction in meaning and in context should be translated with the English article to connote the truth of the gospel (cf. 3 John 3, 4).

Note the emphatic pronoun “you” (σύ): “You, Gaius, are walking in the truth,” which in the context of schism and conflict contrasts with others known to the elder who are not. The verb “to walk” (περιπατεῖν) is used metaphorically to refer to how one lives one’s life, occurring five times in 1 John (1:6, 7; 2:6 [2x], 11), three times in 2 John (vv. 4, 6 [2x]), and twice in 3 John (vv. 3, 4). Because it is clear to others that Gaius is living his life consistently with the truth revealed in the gospel of Jesus Christ, the elder hopes that all the circumstances of Gaius’s life are going well and that he is in good health (v. 2). The plural noun and participles in the genitive absolute (“brothers coming and testifying”; ἐρχομένων ἀδελφῶν καὶ μαρτυρούντων) suggest an unspecified number of brothers who had previously enjoyed Gaius’s hospitality, perhaps on a number of different occasions.

The word “brother” (ἀδελφός) is used throughout the NT to refer to fellow Christians, and in the plural is a generic masculine used even where women are included in the group (e.g., Rom 1:13; 1 Cor 1:11; Eph 6:23; 1 Thess 1:4; Heb 13:22; Jas 1:2). Though it is not clear whether women believers are among the “brothers” mentioned here, women in the first century did travel between churches, such as Priscilla with her husband, Aquila (Acts 18:18), and Phoebe, who carried Paul’s letter from Corinth to Rome (Rom 16:1). Here in 3 John the “brothers” are most likely traveling preachers and teachers associated with the elder and sent out from his church with his blessing. The fact that women traveled with Jesus and the Twelve (Luke 8:1–3) opens the possibility that women may have been among the earliest evangelists and teachers in the wider church, but little work has been done to confirm this. If the elder is the apostle John, his presumably advanced age might have made it difficult for him to travel.

The elder “rejoices greatly” (ἐχάρην … λίαν) when he hears reports that believers are living their lives in accord with the gospel of Jesus Christ as received and taught by the elder. The phrase “I rejoice greatly” is another conventional expression in some Hellenistic letters in response to a letter or to good news.21 However, here it is more than a platitude as v. 4 makes clear. In a time of conflict created by the teaching of the antichrists (1 John 2:18–25) and the rejection of Diotrephes (3 John 9–10), the loyalty of those who remained faithful to the apostolic teaching would be important to the elder.

The verb “to testify” (μαρτυρέω) is often found in letters of recommendation during the Roman period, though with a somewhat different use than here.22 Kim points out that letters of introduction may attempt to motivate the recipient to receive and do something on behalf of the introduced individual so that “he may bear witness to me,” acknowledging that the recipient of the letter has done what was requested. In other words, testimony that the recipient has complied with the request of the writer closes the loop of communication, so to speak. In 3 John the previously sent envoys have done just that; they have “spoken well” of Gaius’s welcome in the past, and “before the church” at that (v. 6).

4 I have no greater joy than these times when I hear that my children are walking in the truth (μειζοτέραν τούτων οὐκ ἔχω χαράν, ἵνα ἀκούω τὰ ἐμὰ τέκνα ἐν τῇ ἀληθείᾳ περιπατοῦντα). The specific instance of joy caused by Gaius’s faithfulness (v. 3) is generalized here in v. 4 to all who are faithful to the truth. The separation of the comparative adjective “greater” (μειζοτέραν) from the noun it modifies, “joy” (χαράν), marks semantic prominence of the phrase, which is further emphasized by its position in front of the negated verb. This emphatic construction indicates that while the phrase in v. 3, “for I rejoice greatly,” may be conventional to the letter form, it is certainly not mere platitude.

Note that the comparative genitive is plural (τούτων), even though most English translations render it as the singular “this” to achieve good English style. The plural demonstrative pronoun is probably a reference to the several times when the elder has heard a good report about his children (τὰ ἐμὰ τέκνα, plural) in the next clause. The elder apparently is thinking of the great joy he takes each time he hears of a faithful believer.

The hina clause is appositional, defining the cause of joy. As Wallace notes, this use of a hina clause is almost idiomatic in the Johannine corpus.23 Also characteristic of Johannine writing is the use of the possessive adjective “mine” (ἐμά) instead of the more common genitive personal pronoun “of me” ([ἐ]μου).

Despite any differences with 1 and 2 John, the criterion of the elder’s joy is the same—seeing Christians living out the truth of the gospel of Jesus Christ, as defined by the tradition in which the elder stands (cf. 1 John 1:1–4). There is nothing that pleases the elder more than to see Christians faithfully adhering to the apostolic teaching about Christ. The Venerable Bede’s comment on this verse continues to resonate with pastors and others in Christian leadership: “There is no greater joy than to know that those who have heard the gospel are now putting it into practice by the way in which they live.”24

The elder apparently views his spiritual oversight paternally, for he refers to his “children” (τέκνα), of which Gaius is apparently one prime example. The apostle Paul also referred to those he led to faith in Christ as his “children” (1 Cor 4:14; Gal 4:19; Phil 2:22), but in the Johannine letters the phrase seems to have a broader sense of those over whom the elder has spiritual oversight (1 John 2:1; 2 John 1, 4, 13). The two thoughts are not, of course, mutually exclusive.

The elder’s declaration of what gives him the greatest joy is at the same time an implicit exhortation that his dear friend Gaius will continue to give him joy by continuing to walk in the truth. This implicit exhortation prepares Gaius to respond positively to the elder’s request that follows in v. 6 and culminates in v. 11, where the only imperative verb in the body of the letter is found. (The other imperative form “greet” [ἀσπάζου] in v. 15 is formulaic for letter closings.)

Theology in Application

Truth and Love, Again

In 3 John 1–4, the noun “truth” (ἀλήθεια) is mentioned four times, making it the central theme of a passage that functions rhetorically to introduce a major theme of the letter and joining it to what is said about truth in the other Johannine writings. The closely associated theme “love” (ἀγαπάω and its cognates) is mentioned three times in these verses. These opening verses make clear that the basis for such a bond of love between believers is the shared value of living one’s life in accordance with the truth of the gospel of Jesus Christ, who is himself the Truth (John 14:6). Even though 3 John does not mention “Jesus” or “Christ,” the truth in view is clearly the Christian gospel, not only because the rest of the Johannine corpus is so explicitly centered on Jesus Christ, but also because the itinerant teaching in view in 3 John is being done for the sake of “the Name” (v. 7, see comments), an allusion to Jesus Christ and the only name in which salvation is found (Acts 4:12) and to which all will one day bow (Phil 2:9–10).

Centered in the gospel of Jesus Christ, John’s teachings define the nature of both truth and love and their relationship to one another, concepts that had to be redeemed in the first century and that are terribly abused and distorted in our times as well. As Wilson notes:

Love is a terribly debased term today, almost beyond rescue as a description of the good news of the kingdom come in Jesus Christ…. We must work to recover an understanding and practice of love…. Salvation is living in the way of love.25

The concept of truth also fares poorly in a postmodern age that revels in relativism and pluralism. By referring to the gospel of Jesus Christ as “the truth,” the elder is making a bold claim in his time (cf. John 18:38). The early church lived in a world that was possibly even more pluralistic than ours, with a plethora of religions and philosophies vying for the hearts and minds of people. The elder identifies the gospel of Jesus Christ as truth, not simply in the cognitive sense, but as the existential reality that demands to be lived out by those who call themselves followers of Christ. The elder considers his apostolic ministry to be successful only when those over whom he has spiritual influence are living their lives in a manner consistent with that truth in such a way as can be observed and affirmed by all who know them. The elder rejoices that Gaius is no closet Christian, whose religion is so private that it finds no public expression, but is known by others for his faithfulness to the truth because of his way of life.

This brief note to Gaius exposes the nature of the relationship between Christian truth and Christian love as it is brought to bear on the topic of Christian hospitality later in the letter. Although hospitality may initially seem a rather mundane issue in light of the awesome realities revealed by Jesus Christ, it is in the details of living that the elder looks for an understanding of the gospel that keeps truth and love in right relationship in times of conflict and schism.

If love and truth are visualized as two concepts weighed on a balance scale, with the goal of keeping them in balance, they will always be in conflict to some extent in our thinking. In our modern ethos, defending the truth and loving others are often put in opposition by a postmodern view that argues that any claim to truth is a power play that insults, and perhaps oppresses, those with a differing viewpoint. Christians who think that love trumps truth tend to argue for acceptance—or at least tolerance—of beliefs and practices that are clearly in conflict with scriptural truth, and they are buying into the ethos of relativism more than they perhaps realize.

By contrast, some Christians, convinced that they have God’s truth, tend to defend it, especially against other Christians, by using the most vitriolic and mean-spirited tactics. The distance from virtue to evil is sometimes not great. I’ve heard it said that it is a small step from being willing to die for the truth to be willing to kill for it—a thought that looms large in the wake of religiously motivated terrorists convinced they know God’s truth. Therefore the biblical relationship between truth and love must be understood and held together in our thinking. Holding that love and truth are in tension shows an inadequate and unbiblical view of both concepts.

Love Doesn’t Trump Truth

Contrary to the values of modern society, the NT teaches that it is not loving to encourage someone to live in ways counter to the truth that God has revealed, that is, to aid and abet someone in their sin, especially those who claim to be Christian (1 Cor 5:2). Whether the sin is wrong belief about Christ or disobedience to the way of life Christ commands, the elder does not want Christians to be a part of it. Christians today need to hear the elder clearly on this relationship between truth and love and to think carefully about what supports the truth. The matter comes down to discerning truth from falsehood.

The Johannine letters are exhortations to remain faithful to the truth revealed by God through Jesus, who then commissioned his apostles to proclaim it. Where is that truth to be found today? Although some denominations today wish to retain the office of “apostle,” there must be a clear distinction between divinely inspired writers of the NT and anyone who claims the title of apostle today. At the time 3 John was written, the NT did not yet exist; thus, it was important to know whom to listen to, and it no doubt was confusing. But today the apostolic teaching about Christ is found within the pages of the NT. Only those who teach and preach the divinely inspired message of the NT stand in the apostolic tradition today. That excludes those—especially who call themselves Christian—who reject the Bible as God’s Word and take it to be just an ancient book whose content is mostly irrelevant to modern issues.

The elder is still exercising his apostolic oversight through the words of this letter. Gaius becomes an “everyman” of the Christian faith with whom we can identify as we hear the elder’s words exhorting us also to live our lives in faithfulness to the gospel of Jesus Christ. The positive example of Gaius, who was widely known for living out the Christian faith by putting his resources into service for others, is a model worthy of imitation. As Christian apologist Josh McDowell once asked, “If we were on trial for being a Christian would there be enough evidence to convict us?”26