Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that; I’m right and I will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first – rock ’n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.

John Lennon

In the past twenty years, we have realized that the heart of your culture is your religion: Christianity. That is why the West has been so powerful. The Christian moral foundation of social and cultural life was what made possible the emergence of capitalism and then the successful transition to democratic politics. We don’t have any doubt about this.

Anonymous Fellow of the Chinese Academy of the Social Sciences

In the course of roughly 500 years, as we have seen, Western civilization rose to a position of extraordinary dominance in the world. Western institutional structures like the corporation, the market and the nation-state became the global standards for competitive economics and politics – templates for the Rest to copy. Western science shifted the paradigms; others either followed or were left behind. Western systems of law and the political models derived from them, including democracy, displaced or defeated the non-Western alternatives. Western medicine marginalized the witch doctors and other faith-healers. Above all, the Western model of industrial production and mass consumption left all alternative models of economic organization floundering in its wake. Even in the late 1990s the West was still clearly the dominant civilization of the world. The five leading Western powers – the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, France and Canada – accounted for 44 per cent of total global manufacturing between them. The scientific world was dominated by Western universities, employees of which won the lion’s share of Nobel prizes and other distinctions. A democratic wave was sweeping the world, most spectacularly in the wake of the 1989 revolutions. Western consumer brands like Levi’s and Coca-Cola flourished almost everywhere; the golden arches of McDonald’s were likewise to be seen in all the major cities in the world. Not only had the Soviet Union collapsed; Japan, which some had predicted would overtake the United States, had stumbled and slid into a lost decade of near-zero growth and deflation. Analysts of international relations struggled to find words sufficiently grand to describe the ascendancy of the United States, the leading power of the Western world: was it an empire? A hegemon? A hyperpuissance?

At the time of writing, in the wake of two burst financial bubbles, two unexpectedly difficult wars, one great recession – and above all in the wake of China’s remarkable ascent to displace Japan as the world’s second-largest economy – the question is whether or not the half-millennium of Western predominance is now finally drawing to a close.

Are we living through the descent of the West? It would not be the first time. Here is how Edward Gibbon described the Goths’ sack of Rome in August 410 AD:

in the hour of savage license, when every passion was inflamed, and every restraint was removed … a cruel slaughter was made of the Romans; and … the streets of the city were filled with dead bodies, which remained without burial during the general consternation … Whenever the Barbarians were provoked by opposition, they extended the promiscuous massacre to the feeble, the innocent, and the helpless … The matrons and virgins of Rome were exposed to injuries more dreadful, in the apprehension of chastity, than death itself … The brutal soldiers satisfied their sensual appetites, without consulting either the inclination or the duties of their female captives … In the pillage of Rome, a just preference was given to gold and jewels … but, after these portable riches had been removed by the more diligent robbers, the palaces of Rome were rudely stripped of their splendid and costly furniture …

The acquisition of riches served only to stimulate the avarice of the rapacious Barbarians, who proceeded, by threats, by blows, and by tortures, to force from their prisoners the confession of hidden treasure … It was not easy to compute the multitudes, who, from an honourable station and a prosperous fortune, were suddenly reduced to the miserable condition of captives and exiles … The calamities of Rome … dispersed the inhabitants to the most lonely, the most secure, the most distant places of refuge.1

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, tells the story of the last time the West collapsed. Today, many people in the West fear we may be living through a kind of sequel. When you reflect on what caused the fall of ancient Rome, such fears appear not altogether fanciful. Economic crisis; epidemics that ravaged the population; immigrants overrunning the imperial borders; the rise of a rival empire – Persia’s – in the East; terror in the form of Alaric’s Goths and Attila’s Huns. Is it possible that, after so many centuries of supremacy, we now face a similar conjuncture? Economically, the West is stagnating in the wake of the worst financial crisis since the Depression, while many of the Rest are growing at unprecedented rates. We live in fear of pandemics and man-made changes to the global climate. There is alarming evidence that some immigrant communities within our societies have become seedbeds for Islamist ideology and terrorist networks. A nuclear terrorist attack would be far more devastating to London or New York than the Goths were to Rome. Meanwhile, a rival empire is on the rise in the East: China, which could conceivably become the biggest economy in the world within the next two decades.

Gibbon’s most provocative argument in the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was that Christianity was one of the fatal solvents of the first version of Western civilization. Monotheism, with its emphasis on the hereafter, was fundamentally at odds with the variegated paganism of the empire in its heyday. Yet it was a very specific form of Christianity – the variant that arose in Western Europe in the sixteenth century – that gave the modern version of Western civilization the sixth of its key advantages over the rest of the world: Protestantism – or, rather, the peculiar ethic of hard work and thrift with which it came to be associated. It is time to understand the role God played in the rise of the West, and to explain why, in the late twentieth century, so many Westerners turned their backs on Him.

If you were a wealthy industrialist living in Europe in the late nineteenth century, there was a disproportionate chance that you were a Protestant. Since the Reformation, which had led many northern European states to break away from the Roman Catholic Church, there had been a shift of economic power away from Catholic countries like Austria, France, Italy, Portugal and Spain and towards Protestant countries such as England, Holland, Prussia, Saxony and Scotland. It seemed as if the forms of faith and ways of worship were in some way correlated with people’s economic fortunes. The question was: what was different about Protestantism? What was it about the teaching of Luther and his successors that encouraged people not just to work hard but also to accumulate capital? The man who came up with the most influential answer to these questions was a depressive German professor named Max Weber – the father of modern sociology and the author who coined the phrase ‘the Protestant ethic’.

Weber was a precocious youth. Growing up in Erfurt, one of the strongholds of the German Reformation, the thirteen-year-old Weber gave his parents as a Christmas present an essay entitled ‘About the Course of German History, with Special Reference to the Positions of the Emperor and the Pope’. At the age of fourteen, he was writing letters studded with references to classical authors from Cicero to Virgil and already had an extensive knowledge of the philosophy of, among others, Kant and Spinoza. His early academic career was one triumph after another: at the age of twenty-two he was already a qualified barrister. Within three years he had a doctorate for a thesis on ‘The History of Medieval Business Organizations’ and at twenty-seven his Habilitation on ‘Roman Agrarian History and its Significance for Private Law’ secured him a lectureship at the University of Berlin. He was appointed professor of economics at Freiburg at the age of thirty, winning fame and notoriety for his inaugural lecture, which called for a more ambitious German imperialism.

This arc of academic ascent was painfully interrupted in 1897, when Weber suffered a paralysing nervous breakdown, precipitated by the death of his father following a bitter row between them. In 1899 he felt obliged to resign his academic post. He spent three years recuperating, in the course of which he became increasingly preoccupied with religion and its relationship to economic life. His parents had both been Protestants; indeed, his maternal grandfather was a devout Calvinist, while his other grandfather was a successful linen merchant. His mother was a true Calvinist in her asceticism; his father, by contrast, was a bon vivant, living life to the full thanks to an inherited fortune. The link between religious and economic life was the puzzle at the heart of Weber’s own existence. Which of his parents had the right attitude to worldly wealth?

Until the Reformation, Christian religious devotion had been seen as something distinct from the material affairs of the world. Lending money at interest was a sin. Rich men were less likely than the poor to enter the Kingdom of Heaven. Rewards for a pious life lay in the afterlife. All that had changed after the 1520s, at least in the countries that embraced the Reformation. Reflecting on his own experience, Weber began to wonder what it was about the Reformation that had made the north of Europe more friendly towards capitalism than the south. It took a transatlantic trip to provide the answer.

In 1904 Weber travelled to St Louis, Missouri, to attend the Congress of Arts and Sciences at the World Fair.2 The park where the World Fair was held covered more than 200 acres and yet still seemed to overflow with everything that American capitalism had to offer. Weber was dazzled by the shining lights of the Palace of Electricity. The Alternating Current King, Thomas Edison himself, was on hand, the personification of American entrepreneurship. St Louis was brimming with marvels of modern technology, from telephones to motion pictures. What could possibly explain the dynamism of this society, which made even industrial Germany seem staid and slow moving? Almost manically restless, Weber rushed around the United States in search of an answer. A caricature of the absent-minded German professor, he made a lasting impression on his American cousins Lola and Maggie Fallenstein, who were especially struck by his rather bizarre outfit, a checked brown suit with plus-fours and brown knee-socks. But that was nothing compared with the impression America made on Weber. Travelling by train from St Louis to Oklahoma, passing through small Missouri towns like Bourbon and Cuba, Weber finally got it:

This kind of place is really an incredible thing: tent camps of the workers, especially section hands for the numerous railroads under construction; ‘streets’ in a natural state, usually doused with petroleum twice each summer to prevent dust, and smelling accordingly; wooden churches of at least 4–5 denominations … Add to this the usual tangle of telegraph and telephone wires, and electrical trainlines under construction, for the ‘town’ extends into the unbounded distance.3

The little town of St James, about 100 miles west of St Louis, is typical of the thousands of new settlements that sprang up along the railroads as they spread westwards across America. When Weber passed through it a hundred years ago, he was amazed at the town’s huge number of churches and chapels of every stripe. With the industrial extravaganza of the World Fair still fresh in his memory, he began to discern a kind of holy alliance between America’s material success and its vibrant religious life.

When Weber returned to his study in Heidelberg he wrote the second part of his seminal two-part essay, ‘The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism’. It contains one of the most influential of all arguments about Western civilization: that its economic dynamism was an unintended consequence of the Protestant Reformation. Whereas other religions associated holiness with the renunciation of worldly things – monks in cloisters, hermits in caves – the Protestant sects saw industry and thrift as expressions of a new kind of hard-working godliness. The capitalist ‘calling’ was, in other words, religious in origin: ‘To attain … self-confidence [in one’s membership of the Elect] intense worldly activity is recommended … [Thus] Christian asceticism … strode into the market-place of life.’4 ‘Tireless labour’, as Weber called it, was the surest sign that you belonged to the Elect, that select band of people predestined by God for salvation. Protestantism, he argued, ‘has the effect of liberating the acquisition of wealth from the inhibitions of traditionalist ethics; it breaks the fetters on the striving for gain not only by legalizing it, but … by seeing it as directly willed by God’. The Protestant ethic, moreover, provided the capitalist with ‘sober, conscientious, and unusually capable workers, who were devoted to work as the divinely willed purpose of life’.5 For most of history, men had worked to live. But the Protestants lived to work. It was this work ethic, Weber argued, that gave birth to modern capitalism, which he defined as ‘sober, bourgeois capitalism with its rational organization of free labour’.6

Weber’s thesis is not without its problems. He saw ‘rational conduct on the basis of the idea of the calling’ as ‘one of the fundamental elements of the spirit of modern capitalism’.7 But elsewhere he acknowledged the irrational character of ‘Christian asceticism’: ‘The ideal type of the capitalistic entrepreneur … gets nothing out of his wealth for himself, except the irrational sense of having done his job well’; he ‘exists for the sake of his business, instead of the reverse’, which ‘from the view-point of personal happiness’ was once again ‘irrational’.8 Even more problematic was Weber’s scathing sideswipe at the Jews, who posed the most obvious exception to his argument.* ‘The Jews’, according to Weber, ‘stood on the side of the politically and speculatively oriented adventurous capitalism; their ethos was … that of pariah-capitalism. Only Puritanism carried the ethos of the rational organization of capital and labour.’9 Weber was also mysteriously blind to the success of Catholic entrepreneurs in France, Belgium and elsewhere. Indeed, his handling of evidence is one of the more glaring defects of his essay. The words of Martin Luther and the Westminster Confession sit uneasily alongside quotations from Benjamin Franklin and some distinctly unsatisfactory data from the German state of Baden about Protestant and Catholic educational attainment and income. Later scholars, notably the Fabian economic historian R. H. Tawney, have tended to cast doubt on Weber’s underlying argument that the direction of causation ran from religious doctrine to economic behaviour.10 On the contrary, much of the first steps towards a spirit of capitalism occurred before the Reformation, in the towns of Lombardy and Flanders; while many leading reformers expressed distinctly anti-capitalist views. At least one major empirical study of 276 German cities between 1300 and 1900 found ‘no effects of Protestantism on economic growth’, at least as measured by the growth of city size.11 Some cross-country studies have arrived at similar conclusions.12

Nevertheless, there are reasons to think that Weber was on to something, even if he was right for the wrong reasons. There was indeed, as he assumed, a clear tendency after the Reformation for Protestant countries in Europe to grow faster than Catholic ones, so that by 1700 the former had clearly overtaken the latter in terms of per-capita income, and by 1940 people in Catholic countries were on average 40 per cent worse off than people in Protestant countries.13 Protestant former colonies have also fared better economically than Catholic ones since the 1950s, even if religion is not a sufficient explanation for that difference.14 Because of the central importance in Luther’s thought of individual reading of the Bible, Protestantism encouraged literacy, not to mention printing, and these two things unquestionably encouraged economic development (the accumulation of ‘human capital’) as well as scientific study.15 This proposition holds good not just for countries such as Scotland, where spending on education, school enrolment and literacy rates were exceptionally high, but for the Protestant world as a whole. Wherever Protestant missionaries went, they promoted literacy, with measurable long-term benefits to the societies they sought to educate; the same cannot be said of Catholic missionaries throughout the period from the Counter-Reformation to the reforms of the Second Vatican Council (1962–5).16 It was the Protestant missionaries who were responsible for the fact that school enrolments in British colonies were, on average, four to five times higher than in other countries’ colonies. In 1941 over 55 per cent of people in what is now Kerala were literate, a higher proportion than in any other region of India, four times higher than the Indian average and comparable with the rates in poorer European countries like Portugal. This was because Protestant missionaries were more active in Kerala, drawn by its ancient Christian community, than anywhere else in India. Where Protestant missionaries were not present (for example, in Muslim regions or protectorates like Bhutan, Nepal and Sikkim), people in British colonies were not measurably better educated.17 The level of Protestant missionary activity has also proved to be a very good predictor of post-independence economic performance and political stability. Recent surveys of attitudes show that Protestants have unusually high levels of mutual trust, an important precondition for the development of efficient credit networks.18 More generally, religious belief (as opposed to formal observance) of any sort appears to be associated with economic growth, particularly where concepts of heaven and hell provide incentives for good behaviour in this world. This tends to mean not only hard work and mutual trust but also thrift, honesty, trust and openness to strangers, all economically beneficial traits.19

Religions matter. In earlier chapters, we saw how the ‘stability ethic’ of Confucianism played a part in imperial China’s failure to develop the kind of competitive institutional framework that promoted innovation in Western Europe – even if China was far from the static, unchanging society described by Weber in his sequel to ‘The Protestant Ethic’, Confucianism and Taoism (1916). We saw how the power of the imams and mullahs snuffed out any chance of a scientific revolution in the Islamic world. And we saw how the Roman Catholic Church acted as one of the brakes on economic development in South America. But perhaps the biggest contribution of religion to the history of Western civilization was this. Protestantism made the West not only work, but also save and read. The Industrial Revolution was indeed a product of technological innovation and consumption. But it also required an increase in the intensity and duration of work, combined with the accumulation of capital through saving and investment. Above all, it depended on the accumulation of human capital. The literacy that Protestantism promoted was vital to all of this. On reflection, we would do better to talk about the Protestant word ethic.

The question is: has the West today – or at least a significant part of it – lost both its religion and the ethic that went with it?

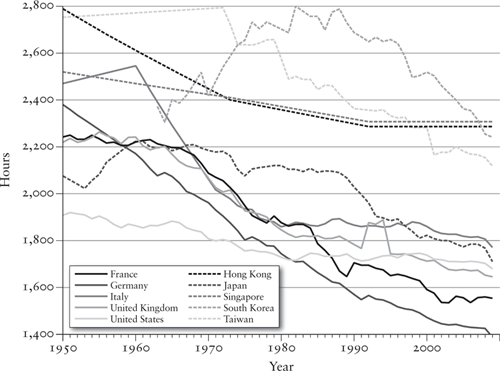

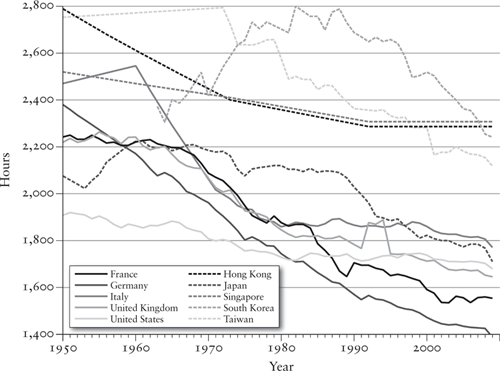

Europeans today are the idlers of the world. On average, they work less than Americans and a lot less than Asians. Thanks to protracted education and early retirement, a smaller share of Europeans are actually available for work. For example, 54 per cent of Belgians and Greeks aged over fifteen participate in the labour force, compared with 65 per cent of Americans and 74 per cent of Chinese.20 Of that labour force, a larger proportion was unemployed in Europe than elsewhere in the developed world on average in the years 1980 to 2010. Europeans are also more likely to go on strike.* Above all, thanks to shorter workdays and longer holidays, Europeans work shorter hours.21 Between 2000 and 2009 the average American in employment worked just under 1,711 hours a year (a figure pushed down by the impact of the financial crisis, which put many workers on short time). The average German worked just 1,437 hours – fully 16 per cent less. This is the result of a prolonged period of divergence. In 1979 the differentials between European and American working hours were minor; indeed, in those days the average Spanish worker put in more hours per year than the average American. But, from then on, European working hours declined by as much as a fifth. Asian working hours also declined, but the average Japanese worker still works as many hours a year as the average American, while the average South Korean works 39 per cent more. People in Hong Kong and Singapore also work roughly a third more hours a year than Americans.22

Work Ethics: Hours Worked per Year in the West and the East, 1950–2009

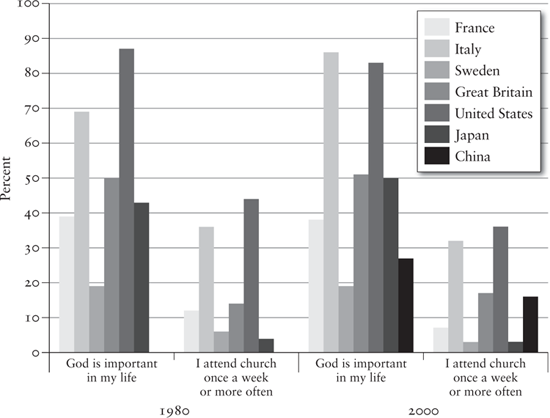

The striking thing is that the transatlantic divergence in working patterns has coincided almost exactly with a comparable divergence in religiosity. Europeans not only work less; they also pray less – and believe less. There was a time when Europe could justly refer to itself as ‘Christendom’. Europeans built the continent’s loveliest edifices to accommodate their acts of worship. They quarrelled bitterly over the distinction between transubstantiation and consubstantiation. As pilgrims, missionaries and conquistadors, they sailed to the four corners of the earth, intent on converting the heathen to the true faith. Now it is Europeans who are the heathens. According to the most recent (2005–8) World Values Survey, 4 per cent of Norwegians and Swedes and 8 per cent of French and Germans attend a church service at least once a week, compared with 36 per cent of Americans, 44 per cent of Indians, 48 per cent of Brazilians and 78 per cent of sub-Saharan Africans. The figures are significantly higher for a number of predominantly Catholic countries like Italy (32 per cent) and Spain (16 per cent). The only countries where religious observance is lower than in Protestant Europe are Russia and Japan. God is ‘very important’ for just one in ten German and Dutch people; the French proportion is only slightly higher. By comparison, 58 per cent of Americans say He is very important in their lives. The importance of God is higher still in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, and highest of all in the Muslim countries of the Middle East. Only in China is God important to fewer people (less than 5 per cent) than in Europe. Just under a third of Americans regard politicians who do not believe in God as unfit for public office, compared with 4 per cent of Norwegians and Swedes, 9 per cent of Finns, 11 per cent of Germans and Spaniards and 12 per cent of Italians. Only half of Indians and Brazilians would tolerate an atheist politician.23 Only in Japan does religious faith matter less in politics than in Western Europe.

Religious Belief and Observance, Early 1980s and Mid-2000s

The case of Britain is especially interesting in view of the determination with which Britons sought to spread their own religious faith in the nineteenth century. Today, according to the World Values Survey, 17 per cent of Britons claim they attend a religious service at least once a week – higher than in continental Europe, but still less than half the American figure. Fewer than a quarter of Britons say God is very important in their lives, again less than half the American figure. True, the UK figures are up slightly since 1981 (when only 14 per cent said they attended church once a week, and under a fifth said God was important to them). But the surveys do not distinguish between religions, so they almost certainly understate the decline of British Christianity. A 2004 study suggested that, in an average week, more Muslims attend a mosque than Anglicans go to church. And nearly all of the recent increase in church attendance is explained by the growth of non-white congregations, especially in Evangelical and Pentecostal churches. When Christian Research conducted a census of 18,720 churches on Sunday 8 May 2005, the real rate of attendance was just 6.3 per cent of the population, down 15 per cent since 1998. On closer inspection, Britain seems to exemplify the collapse both of observance and of faith in Western Europe.

The de-Christianization of Britain is a relatively recent phenomenon. In his Short History of England (1917), G. K. Chesterton took it as almost self-evident that Christianity was synonymous with civilization:

If anyone wishes to know what we mean when we say that Christendom was and is one culture, or one civilization, there is a rough but plain way of putting it. It is by asking what is the most common … of all the uses of the word ‘Christian’ … It has long had one meaning in casual speech among common people, and it means a culture or a civilization. Ben Gunn on Treasure Island did not actually say to Jim Hawkins, ‘I feel myself out of touch with a certain type of civilization’; but he did say, ‘I haven’t tasted Christian food.’24

British Protestants were in truth never especially observant (compared, for example, with Irish Catholics) but until the late 1950s Church membership, if not attendance, was relatively high and steady. Even in 1960 just under a fifth of the population of the United Kingdom were Church members. But by 2000 the fraction was down to a tenth.25 Prior to 1960, most marriages in England and Wales were solemnized in a church; then the slide began, down to around 40 per cent in the late 1990s. For most of the first half of the twentieth century, Anglican Easter Day communicants accounted for around 5 or 6 per cent of the population of England; it was only after 1960 that the proportion slumped to 2 per cent. Figures for the Church of Scotland show a similar trend: steady until 1960, then falling by roughly half. Especially striking is the decline in confirmations. There were 227,135 confirmations in England in 1910; in 2007 there were just 27,900 – and that was 16 per cent fewer than just five years previously. Between 1960 and 1979 the confirmation rate among twelve- to twenty-year-olds fell by more than half, and it continued to plummet thereafter. Fewer than a fifth of those baptized are now confirmed.26 For the Church of Scotland the decline has been even more precipitous.27 No one in London or Edinburgh today would use the word ‘Christian’ in Ben Gunn’s sense.

These trends seem certain to continue. Practising Christians are ageing: 38 per cent of Methodists and members of the United Reformed Church were sixty-five or over in 1999, for example, compared with 16 per cent of the population as a whole.28 Younger Britons are markedly less likely to believe in God or heaven.29 By some measures, Britain is already one of the most godless societies in the world, with 56 per cent of people never attending church at all – the highest rate in Western Europe.30 The 2000 ‘Soul of Britain’ survey conducted for Michael Buerk’s television series revealed an astounding degree of religious atrophy. Only 9 per cent of those surveyed thought the Christian faith was the best path to God; 32 per cent considered all religions equally valid. Although only 8 per cent identified themselves as atheists, 12 per cent confessed they did not know what to believe. More than two-thirds of respondents said they recognized no clearly defined moral guidelines, and fully 85 per cent of those aged under twenty-four. (Bizarrely, 45 per cent of those surveyed said that this decline in religion had made the country a worse place.)

Some of the finest British writers of the twentieth century anticipated Britain’s crisis of faith. The Oxford don C. S. Lewis (best known today for his allegorical children’s stories) wrote The Screwtape Letters (1942) in the hope that mocking the Devil might keep him at bay. Evelyn Waugh knew, as he wrote his wartime Sword of Honour trilogy (1952–61), that he was writing the epitaph of an ancient form of English Roman Catholicism. Both sensed that the Second World War posed a grave threat to Christian faith. Yet it was not until the 1960s that their premonitions of secularization came true. Why, then, did the British lose their historic faith? Like so many difficult questions, this seems at first sight to have an easy answer. But before we can simply blame it, as the poet Philip Larkin did, on ‘The Sixties’ – the Beatles, the contraceptive pill and the mini-skirt – we need to remind ourselves that the United States enjoyed all these earthly delights too, without ceasing to be a Christian country. Ask many Europeans today, and they will say that religious faith is just an anachronism, a vestige of medieval superstition. They will roll their eyes at the religious zeal of the American Bible Belt – not realizing that it is their own lack of faith that is the real anomaly.

Who killed Christianity in Europe, if not John Lennon?31 Was it, as Weber himself predicted, that the spirit of capitalism was bound to destroy its Protestant ethic parent, as materialism corrupted the original asceticism of the godly (the ‘secularization hypothesis’)?32 This was quite close to the view of the novelist and (in old age) holy man Leo Tolstoy, who saw a fundamental contradiction between Christ’s teachings and ‘those habitual conditions of life which we call civilization, culture, art, and science’.33 If so, what part of economic development was specifically hostile to religious belief? Was it the changing role of women and the decline of the nuclear family – which also seems to explain the collapse in family size and the demographic decline of the West? Was it scientific knowledge – what Weber called ‘the demystification of the world’, in particular Darwin’s theory of evolution, which overthrew the biblical story of divine creation? Was it improving life expectancy, which made the hereafter a much less alarmingly proximate destination? Was it the welfare state, a secular shepherd keeping watch over us from the cradle to the grave? Or could it be that European Christianity was killed by the chronic self-obsession of modern culture? Was the murderer of Europe’s Protestant work ethic none other than Sigmund Freud?

In The Future of an Illusion (1928) Sigmund Freud, the Moravian-born founding father of psychoanalysis, set out to refute Weber. For Freud, a lapsed Jew, religion could not be the driving force behind the achievements of Western civilization because it was essentially an ‘illusion’, a ‘universal neurosis’ devised to prevent people from giving way to their basic instincts – in particular, their sexual desires and violent, destructive impulses. Without religion, there would be mayhem:

If one imagined its prohibitions removed, then one could choose any woman who took one’s fancy as one’s sexual object, one could kill without hesitation one’s rival or whoever interfered with one in any other way, and one could seize what one wanted of another man’s goods without asking his leave.34

Religion not only prohibited rampant sexual promiscuity and violence. It also reconciled men to ‘the cruelty of fate, particularly as shown in death’ and the ‘sufferings and privations’ of daily life.35 When the monotheistic religions fused the gods into a single person, ‘man’s relations to him could recover the intimacy and intensity of the child’s relation to the father. If one had done so much for the father, then surely one would be rewarded – at least the only beloved child, the chosen people, would be.’36

Freud had little hope that mankind could wholly emancipate itself from religion, least of all in Europe. As he put it:

If you want to expel religion from our European civilization, you can only do it by means of another system of doctrines; and such a system would from the outset take over all the psychological characteristics of religion – the same sanctity, rigidity and intolerance, the same prohibition of thought – for its own defence.37

That certainly seemed plausible in the 1930s, when both Stalin and Hitler propagated their own monstrous cults. Yet in both cases the totalitarian political religions failed to rein in the primal instincts described in Freud’s theory of religion. By 1945 Europe lay exhausted from an orgy of violence – including shocking sexual violence in the form of mass rape – unlike anything seen since the time of Timur. The initial response in many countries, particularly those (like the Soviet Union) most traumatized by mass murder, was to revert to real religion, and to use its time-honoured comforts to mourn the dead.

By the 1960s, however, a generation too young to remember the years of total war and genocide sought a new post-Christian outlet for their repressed desires. Freud’s own theories, with their negative view of repression and their explicit sympathy with the erotic impulse, surely played a part in tempting Europeans to exit the churches and enter the sex shops. In Civilization and its Discontents (1929–30, but first published in the United States only in 1961), Freud had argued that there was a fundamental ‘antithesis’ between civilization as it then existed and man’s most primal urges:

The existence of this inclination to aggression, which we can detect in ourselves and justly assume to be present in others, is the factor which disturbs our relations with our neighbour and which forces civilization into such a high expenditure [of energy]. In consequence of this primary mutual hostility of human beings, civilized society is perpetually threatened with disintegration. The interest of work in common would not hold it together; instinctual passions are stronger than reasonable interests. Civilization has to use its utmost efforts in order to set limits to man’s aggressive instincts and to hold the manifestations of them in check by psychical reaction-formations. Hence … the restriction upon sexual life, and hence too the … commandment to love one’s neighbour as oneself – a commandment which is really justified by the fact that nothing else runs so strongly counter to the original nature of man … Civilization is a process in the service of Eros, whose purpose is to combine single human individuals, and after that families, then races, peoples and nations, into one great unity, the unity of mankind. Why this has to happen, we do not know; the work of Eros is precisely this … Men are to be libidinally bound to one another … But man’s natural aggressive instinct, the hostility of each against all and of all against each, opposes this programme of civilization. This aggressive instinct is the derivative and the main representative of the death instinct which we have found alongside of Eros and which shares world-dominion with it. And now, I think, the meaning of the evolution of civilization is no longer obscure to us. It must present the struggle between Eros and Death, between the instinct of life and the instinct of destruction, as it works itself out in the human species. This struggle is what all life essentially consists of.38

Reading this, one sees what the Viennese satirist Karl Kraus meant when he said that psychoanalysis was ‘the disease of which it pretends to be the cure’.39 But this was the message interpreted by the hippies as a new commandment: let it all hang out. And so they did. The Hombres’ ‘Let It All Hang Out’ (1967) was one of the lesser anthems of the 1960s, but its opening lines – ‘A preachment, dear friends, you are about to receive / On John Barleycorn, nicotine, and the temptations of Eve’ – summed up nicely what was now on offer.* For the West’s most compelling critics today (not least radical Islamists), the Sixties opened the door to a post-Freudian anti-civilization, characterized by a hedonistic celebration of the pleasures of the self, a rejection of theology in favour of pornography and a renunciation of the Prince of Peace for grotesquely violent films and video games that are best characterized as ‘warnography’.

The trouble with all the theories about the death of Protestantism in Europe is that, whatever they may explain about Europe’s de-Christianization, they explain nothing whatsoever about America’s continued Christian faith. Americans have experienced more or less the same social and cultural changes as Europeans. They have become richer. Their knowledge of science has increased. And they are even more exposed to psychoanalysis and pornography than Europeans. But Protestantism in America has suffered nothing like the decline it has experienced in Europe. On the contrary, God is in some ways as big in America today as He was forty years ago.40 The best evidence is provided by the tens of millions of worshippers who flock to American churches every Sunday.

Paradoxically, the advent of the new 1960s trinity of sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll coincided, in the United States, with a boom in Evangelical Protestantism. The Reverend Billy Graham vied with the Beatles to see who could pack more young people into a stadium. This was not so much a reaction, more a kind of imitation. Speaking at the Miami Rock Festival in 1969, Graham urged the audience to ‘tune into God … Turn on to His power.’41 In 1972 the college Christian group Campus Crusade organized an Evangelical conference in Dallas called Explo ’72 that ended with a concert intended to be the Christian Woodstock (the 1969 rock festival that came to encapsulate the hippy counter-culture).* When Cynthia ‘Plaster Caster’, a Catholic teenager from Chicago, made plaster casts of the erect penises of Jimi Hendrix, Robert Plant and Keith Richards (though most definitely not of Cliff Richard’s), she was merely fulfilling Freud’s vision of the triumph of Eros over Thanatos. God was love, as the bumper stickers said, after all. At one and the same time, America was both born again and porn again.

How can we explain the fact that Western civilization seems to have divided in two: to the east a godless Europe, to the west a God-fearing America? How do we explain the persistence of Christianity in America at a time of its steep decline in Europe? The best answer can be found in Springfield, Missouri, the town they call the ‘Queen of the Ozarks’ and the birthplace of the inter-war highway between Chicago and California, immortalized in Bobby Troup’s 1946 song, ‘(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66’. If Max Weber was impressed by the diversity of Protestant sects when he passed through here a century ago, he would be astonished today. Springfield has roughly one church for every thousand citizens. There are 122 Baptist churches, thirty-six Methodist chapels, twenty-five Churches of Christ and fifteen Churches of God – in all, some 400 Christian places of worship. Now it’s not your kicks you get on Route 66; it’s your crucifix.

The significant thing is that all these churches are involved in a fierce competition for souls. As Weber saw it, individual American Baptists, Methodists and others competed within their local religious communities to show one another who among them was truly godly. But in Springfield today the competition is between churches, and it is just as fierce as the competition between car-dealerships or fast-food joints. Churches here have to be commercially minded in order to attract and retain worshippers and, on that basis, the clear winner is the James River Assembly. To European eyes, it may look more look like a shopping mall or business park, but it is in fact the biggest church in Springfield – indeed, one of the biggest in the entire United States. Its pastor, John Lindell, is a gifted and charismatic preacher who combines old-time scriptural teaching with the kind of stagecraft more often associated with rock ’n’ roll. Indeed, at times he seems like the natural heir of the Jesus Revolution identified by Time magazine in 1971, a rock-inspired Christian youth movement in the spirit of the British rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar (1970). Yet there is also a lean and hungry quality to Lindell; as he makes his pitch for God (‘God, You are so awesome’) he seems less like Ian Gillan (the shaggy Deep Purple singer who sang the part of Jesus on the original Superstar album) and more like Steve Jobs, unveiling the latest handheld device from Apple: iGod, maybe. For Lindell, the Protestant ethic is alive and well and living in Springfield. He has no doubt that their faith makes the members of his congregation harder working than they would otherwise be. He himself is quite a worker: three hyperkinetic services in one Sunday is no light preaching load. And the Holy Ghost seems to fuse with the spirit of capitalism as the collection buckets go around – though thankfully not in the brazen manner favoured by Mac Hammond of the Living Word Christian Centre in Minneapolis, who promises ‘Bible principles that will enhance your spiritual growth and help you to win at work, win in relationships, and win in the financial arena’.42

A visit to James River makes obvious the main difference between European and American Protestantism. Whereas the Reformation was nationalized in Europe, with the creation of established Churches like the Church of England or Scotland’s Kirk, in the United States there was always a strict separation between religion and the state, allowing an open competition between multiple Protestant sects. And this may be the best explanation for the strange death of religion in Europe and its enduring vigour in the United States. In religion as in business, state monopolies are inefficient – even if in some cases the existence of a state religion increases religious participation (where there is a generous subsidy from government and minimal control of clerical appointments).43 More commonly, competition between sects in a free religious market encourages innovations designed to make the experience of worship and Church membership more fulfilling. It is this that has kept religion alive in America.44 (The insight is not entirely novel. Adam Smith made a similar argument in The Wealth of Nations, contrasting countries with established Churches with those allowing competition.)45

Yet there is something about today’s American Evangelicals that would have struck Weber, if not Smith, as suspect. For there is a sense in which many of the most successful sects today flourish precisely because they have developed a kind of consumer Christianity that verges on Wal-Mart worship.46 It is not only easy to drive to and entertaining to watch – not unlike a trip to the multiplex cinema, with soft drinks or Starbucks served on the premises. It also makes remarkably few demands on believers. On the contrary, they get to make demands on God,47 so that prayer at James River often consists of an extended series of requests for the deity to solve personal problems. God the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost has been displaced by God the Analyst, the Agony Uncle and the Personal Trainer. With more than two-fifths of white Americans changing religion at some point in their lives, faith has become paradoxically fickle.48

The only problem with turning religion into just another leisure pursuit is that it means Americans have drifted a very long way from Max Weber’s version of the Protestant ethic, in which deferred gratification was the corollary of capital accumulation. In his words:

Protestant asceticism works with all its force against the uninhibited enjoyment of possessions; it discourages consumption … And if that restraint on consumption is combined with the freedom to strive for profit, the result produced will inevitably be the creation of capital through the ascetic compulsion to save.49

By contrast, we have just lived through an experiment: capitalism without saving. In the United States the household savings rate fell below zero at the height of the housing bubble, as families not only consumed their entire disposable income but also drew down the equity in their homes. The decline of thrift turned out to be a recipe for financial crisis. When house prices began to decline in 2006, a chain reaction began: those who had borrowed more than the value of their homes stopped paying their mortgage interest; those who had invested in securities backed by mortgages suffered large losses; banks that had borrowed large sums to invest in such securities suffered first illiquidity and then insolvency; to avert massive bank failures governments stepped in with bailouts; and a crisis of private debt mutated into a crisis of public debt. Today the total private and public debt burden in the United States is more than three and a half times the size of gross domestic product.50

This was not a uniquely American phenomenon. Variations on the same theme were played in other English-speaking countries: Ireland, the United Kingdom and, to a lesser extent, Australia and Canada – this was the fractal geometry of the age of leverage, with the same-shaped problem recurring in a wide range of sizes. There were bigger real-estate bubbles in most European countries – in the sense that house prices rose further relative to income than in the United States – and much more severe crises of public debt in Portugal, Ireland and Greece, which made the mistake of running very large deficits while in a monetary union with Germany. But the financial crisis of 2007–9, though global in its effects, was not global in its origins. It was a crisis made in the Western world as a result of over-consumption and excess financial leverage. Elsewhere – and especially in Asia – the picture was quite different.

It is generally recognized that savings rates are much higher in the East than in the West. Private debt burdens are much lower; houses are often bought outright or with relatively small mortgages. Other forms of consumer credit play a much smaller role. It is also well known, as we have seen, that Asians work many more hours per year than their Western counterparts – average annual hours worked range from 2,120 in Taiwan to 2,243 in South Korea. What is less appreciated is that the rise of thrift and industry in Asia has gone hand in hand with one of the most surprising side-effects of Westernization: the growth of Christianity, above all in China.

The rise of the spirit of capitalism in China is a story everyone knows. But what about the rise of the Protestant ethic? According to separate surveys by China Partner and East China Normal University in Shanghai, there are now around 40 million Protestant Christians in China, compared with barely half a million in 1949. Some estimates put the maximum even higher, at 75 or 110 million.51 Include 20 million Catholics, and there could be as many as 130 million Christians in China. Today, indeed, there may already be more practising Christians in China than in Europe.52 Churches are being built at a faster rate in China than anywhere else in the world. And more Bibles are being printed here than in any other country. The Nanjing Amity Printing Company is the biggest Bible manufacturer in the world. Its vast printworks has produced more than 70 million Bibles since the company was founded in 1986, including 50 million copies in Mandarin and other Chinese languages.53 It is possible that, within three decades, Christians will constitute between 20 and 30 per cent of China’s population.54 This should strike us as all the more remarkable when we reflect on how much resistance there has been to the spread of Christianity throughout Chinese history.

The failure of Protestantism to take root in China earlier is something of a puzzle. There were Nestorian Christian missionaries in Tang China as early as the seventh century. The first Roman Catholic church was built in 1299 by Giovanni da Montecorvino, appointed archbishop of Khanbalik in 1307. By the end of the fourteenth century, however, these Christian outposts had largely disappeared as a result of Ming hostility. A second wave of missionaries came in the early seventeenth century, when the Jesuit Matteo Ricci was granted permission to settle in Beijing. There may have been as many as 300,000 Christians in China by the 1700s. Yet 1724 brought another crackdown with the Yongzheng Emperor’s Edict of Expulsion and Confiscation.55

The third Christian wave were the Protestant missions of the nineteenth century. Organizations like the British Missionary Societies sent literally hundreds of evangelists to bring the Good News to the most populous country on earth. The first to arrive was a twenty-five-year-old Englishman named Robert Morrison of the London Missionary Society, who reached Canton (Guangzhou) in 1807. His first step, even before arriving, was to start learning Mandarin and to transcribe the Bible into Chinese characters. Once in Canton, he set to work on a Latin–Chinese dictionary. By 1814, now in the employment of the East India Company, Morrison had completed translations of the Acts of the Apostles (1810), the Gospel of St Luke (1811), the New Testament (1812) and the Book of Genesis (1814), as well as A Summary of the Doctrine of Divine Redemption (1811) and An Annotated Catechism in the Teaching of Christ (1812). This was enough to persuade the East India Company to permit the import of a printing press and a mechanic to operate it.56 When the Company later dismissed him, for fear of incurring the wrath of the Chinese authorities, Morrison pressed on undaunted, moving to Malacca to set up an Anglo-Chinese College for the ‘cultivation of European and Chinese literature and science, but chiefly for the diffusion of Christianity through the Eastern Archipelago’, finishing his translation of the Bible, a joint effort with William Milne (published in 1823), and producing an English grammar for Chinese students as well as a complete English–Chinese dictionary. By the time Morrison followed his first wife and son to the grave in Canton in 1834 he had added a Vocabulary of the Canton Dialect (1828). Here truly was the Protestant word ethic made flesh.

Yet the efforts of the first British missionaries had unintended consequences. The imperial government had sought to prohibit – on pain of death – Christian proselytizing on the ground that it encouraged popular attitudes ‘very near to bring [sic] a rebellion’:

The said religion neither holds spirits in veneration, nor ancestors in reverence, clearly this is to walk contrary to sound doctrine; and the common people, who follow and familiarize themselves with such delusions, in what respect do they differ from a rebel mob?57

This was prescient. One man in particular responded to Christian proselytizing in the most extreme way imaginable. Hong Xiuquan had hoped to take the traditional path to a career in the imperial civil service, sitting one of the succession of gruelling examinations that determined a man’s fitness for the mandarinate. But he flunked it, and, as so often with exam candidates, failure was followed in short order by complete collapse. In 1833 Hong met William Milne, the co-author with Robert Morrison of the first Chinese Bible, whose influence on him coincided with his emergence from post-exam depression. Doubtless to Milne’s alarm, Hong now announced that he was the younger brother of Jesus Christ. God, he declared, had sent him to rid China of Confucianism – that inward-looking philosophy which saw competition, trade and industriousness as pernicious foreign imports. Hong created a quasi-Christian Society of God Worshippers, which attracted the support of tens of millions of Chinese, mostly from the poorer classes, and proclaimed himself leader of the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace. In Chinese he was known as Taiping Tianguo, hence the name of the uprising he led – the Taiping Rebellion. From Guangxi, the rebels swept to Nanjing, which the self-styled Heavenly King made his capital. By 1853 his followers – who were distinguished by their red jackets, long hair and insistence on strict segregation of the sexes – controlled the entire Yangzi valley. In the throne room there was a banner bearing the words: ‘The order came from God to kill the enemy and to unite all the mountains and rivers into one kingdom.’

For a time it seemed that the Taiping would indeed overthrow the Qing Empire altogether. But the rebels could not take Beijing or Shanghai. Slowly the tide turned against them. In 1864 the Qing army besieged Nanjing. By the time the city fell, Hong was already dead from food poisoning. Just to make sure, the Qing exhumed his cremated remains and fired them out of a cannon. Even after that, it was not until 1871 that the last Taiping army was defeated. The cost in human life was staggering: more than twice that of the First World War to all combatant states. Between 1850 and 1864 an estimated 20 million people in central and southern China lost their lives as the rebellion raged, unleashing famine and pestilence in its wake. By the end of the nineteenth century, many Chinese had concluded that Western missionaries were just another disruptive alien influence on their country, like opium-trading Western merchants. When British missionaries returned to China after the Taiping Rebellion they thus encountered an intensified hostility to foreigners.58

It did not deter them. James Hudson Taylor was twenty-two when he made his first trip to China on behalf of the Chinese Evangelization Society. Unable, as he put it, ‘to bear the sight of a congregation of a thousand or more Christian people rejoicing in their own security [in Brighton] while millions were perishing for lack of knowledge’ overseas, Taylor founded the China Inland Mission in 1865. His preferred strategy was for CIM missionaries to dress in Chinese clothing and to adopt the Qing-era queue (pigtail). Like David Livingstone in Africa, Taylor dispensed both Christian doctrine and modern medicine at his Hangzhou (Hangchow) headquarters.59 Another intrepid CIM fisher of men was George Stott, a one-legged Aberdonian who arrived in China at the age of thirty-one. One of his early moves was to open a bookshop with an adjoining chapel where he harangued a noisy throng, attracted more by curiosity than by a thirst for redemption. His wife opened a girls’ boarding school.60 They and others sought to win converts by using an ingenious new evangelical gadget: the Wordless Book, devised by Charles Haddon Spurgeon to incorporate the key colours of traditional Chinese colour cosmology. In one widely used version, devised by the American Dwight Lyman Moody in 1875, the black page represented sin, the red represented the blood of Jesus, the white represented holiness, and the gold or yellow represented heaven.61

An altogether different tack was taken by Timothy Richard, a Baptist missionary sponsored by the Baptist Missionary Society, who argued that ‘China needed the gospel of love and forgiveness, but she also needed the gospel of material progress and scientific knowledge.’62 Targeting the Chinese elites rather than the impoverished masses, Richard became secretary of the Society for the Diffusion of Christian and General Knowledge among the Chinese in 1891 and was an important influence on Kang Yu Wei’s Self-Strengthening Movement, as well as an adviser to the Emperor himself. It was Richard who secured the creation of the first Western-style university, at Shanxi (Shansi), opened in 1902.

By 1877 there were eighteen different Christian missions active in China as well as three Bible societies. The idiosyncratic Taylor was especially successful at recruiting new missionaries, including an unusually large number of single women, not only from Britain but also from the United States and Australia.63 In the best Protestant tradition, the rival missions competed furiously with one another, the CIM and BMS waging an especially fierce turf war in Shanxi. In 1900, however, xenophobia erupted once again in the Boxer Rebellion, as another bizarre cult, the Righteous and Harmonious Fist (yihe quan), sought to drive all ‘foreign devils’ from the land – this time with the explicit approval of the Empress Dowager. Before the intervention of a multinational force and the suppression of the Boxers, fifty-eight CIM missionaries perished, along with twenty-one of their children.

The missionaries had planted many seeds but, in the increasingly chaotic conditions that followed the eventual overthrow of the Qing dynasty, these sprouted only to wither. The founder of the first Chinese Republic, Sun Yat-sen, was a Christian from Guandong, but he died in 1924 with China on the brink of civil war. Then the nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek and his wife – both Christians* – lost out to the communists in China’s long civil war and ended up having to flee to Taiwan. Shortly after the 1949 Revolution, Zhou Enlai and Y. T. Wu drew up a ‘Christian Manifesto’ designed to undercut the position of missionaries on the grounds of both ideology and patriotism.64 Between 1950 and 1952 the CIM opted to evacuate its personnel from the People’s Republic.65 With the missionaries gone, most churches were closed down or turned into factories. They remained closed for the next thirty years. Christians like Wang Mingdao, Allen Yuan and Moses Xie, who refused to join the Party-controlled Protestant Three-Self Patriotic Movement, were jailed (in each case for twenty or more years).66 The calamitous years of the misnamed Great Leap Forward (1958–62) – in reality a man-made famine that claimed around 45 million lives67 – saw a fresh wave of church closures. There was full-blown iconoclasm during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), which also led to the destruction of many ancient Buddhist temples. Mao himself, ‘the Messiah of the Working People’, became the object of a personality cult even more demented than those of Hitler and Stalin.68 His leftist wife Jiang Qing declared that Christianity in China had been consigned to the museum.69

To Max Weber and many later twentieth-century Western experts, then, it is not surprising that the probability of a Protestantization of China and, therefore, of its industrialization seemed negligibly low – almost as low as a de-Christianization of Europe. The choice for China seemed to be a stark one between Confucian stasis and chaos. That makes the immense changes of our own time all the more breathtaking.

The city of Wenzhou, in Zhejiang province, south of Shanghai, is the quintessential manufacturing town. With a population of 8 million people and growing, it has the reputation of being the most entrepreneurial city in China – a place where the free market rules and the role of the state is minimal. The landscape of textile mills and heaps of coal would have been instantly recognizable to a Victorian; it is an Asian Manchester. The work ethic animates everyone from the wealthiest entrepreneur to the lowliest factory hand. Wenzhou people not only work longer hours than Americans; they also save a far larger proportion of their income. Between 2001 and 2007, at a time when American savings collapsed, the Chinese savings rate rose above 40 per cent of gross national income. On average, Chinese households save more than a fifth of the money they make; corporations save even more in the form of retained earnings.

The truly fascinating thing, however, is that people in Wenzhou have imported more than just the work ethic from the West. They have imported Protestantism too. For the seeds the British missionaries planted here 150 years ago have belatedly sprouted in the most extraordinary fashion. Whereas before the Cultural Revolution there were 480 churches in the city, today there are 1,339 – and those are only the ones approved by the government. The church George Stott built a hundred years ago is now packed every Sunday. Another, established by the Inland Mission in 1877 but closed during the Cultural Revolution and only reopened in 1982, now has a congregation of 1,200. There are new churches, too, often with bright red neon crosses on their roofs. Small wonder they call Wenzhou the Chinese Jerusalem. Already in 2002 around 14 per cent of Wenzhou’s population were Christians; the proportion today is surely higher. And this is the city that Mao proclaimed ‘religion free’ back in 1958. As recently as 1997, officials here launched a campaign to ‘remove the crosses’. Now they seem to have given up. In the countryside around Wenzhou, villages openly compete to see whose church has the highest spire.

Christianity in China today is far from being the opium of the masses.70 Among Wenzhou’s most devout believers are the so-called Boss Christians, entrepreneurs like Hanping Zhang, chairman of Aihao (the Chinese character for which can mean ‘love’, ‘goodness’ or ‘hobby’), one of the three biggest pen-manufacturers in the world. A devout Christian, Zhang is the living embodiment of the link between the spirit of capitalism and the Protestant ethic, precisely as Max Weber understood it. Once a farmer, he started a plastics business in 1979 and eight years later opened his first pen factory. Today he employs around 5,000 workers who produce up to 500 million pens a year. In his eyes, Christianity is thriving in China because it offers an ethical framework to people struggling to cope with a startlingly fast social transition from communism to capitalism. Trust is in short supply in today’s China, he told me. Government officials are often corrupt. Business counterparties cheat. Workers steal from their employers. Young women marry and then vanish with hard-earned dowries. Baby food is knowingly produced with toxic ingredients, school buildings constructed with defective materials. But Zhang feels he can trust his fellow Christians, because he knows they are both hard working and honest.71 Just as in Protestant Europe and America in the early days of the Industrial Revolution, religious communities double as both credit networks and supply chains of creditworthy, trustworthy fellow believers.

In the past, the Chinese authorities were deeply suspicious of Christianity, and not just because they recalled the chaos caused by the Taiping Rebellion. Seminary students played an important part in the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy movement; indeed, two of the most wanted student leaders back in the summer of 1989 subsequently became Christian clergymen. In the wake of that crisis there was yet another crackdown on unofficial churches.72 Ironically, the utopianism of Maoism created an appetite that today, with a Party leadership that is more technocratic than messianic, only Christianity seems able to satisfy.73 And, just as in the time of the Taiping Rebellion, some modern Chinese are inspired by Christianity to embrace decidedly weird cults. Members of the Eastern Lightning movement, which is active in Henan and Heilongjiang provinces, believe that Jesus has returned as a woman. They engage in bloody battles with their arch-rivals, the Three Grades of Servants.74 Another radical quasi-Christian movement is Peter Xu’s Born-Again Movement, also known as the Total Scope Church or the Shouters because of their noisy style of worship, in which weeping is mandatory. Such sects are seen by the authorities as xiejiao, or (implicitly evil) cults, like the banned Falun Gong breathing-practice movement.75 It is not hard to see why the Party prefers to reheat Confucianism, with its emphasis on respect for the older generation and the traditional equilibrium of a ‘harmonious society’.76 Nor is it surprising that persecution of Christians was stepped up during the 2008 Olympics, a time of maximum exposure of the nation’s capital to foreign influences.77

Even under Mao, however, an official Protestantism was tolerated in the form of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement based on the principles of self-governance, self-support and self-propagation – in other words no foreign influences.78 Today, St Paul’s in Nanjing is typical of official Three-Self churches; here, the Reverend Kan Renping’s congregation has grown from a few hundred when he took over in 1994 to some 5,000 regular worshippers. It is so popular that newcomers have to watch the proceedings on closed-circuit television in four nearby satellite chapels. Since the issue of Party Document Number 19 in 1982 there has also been intermittent official tolerance of the ‘house churches’ movement, congregations that meet more or less secretly in people’s homes and often embrace American forms of worship.79 In Beijing itself, worshippers flock to the Reverend Jin Mingri’s Zion Church, an unofficial church with 350 members, nearly all drawn from the entrepreneurial or professional class and nearly all under the age of forty. Christianity has become chic in China. The former Olympic soccer goalkeeper Gao Hong is a Christian. So are the television actress Lu Liping and the pop singer Zheng Jun.80 Chinese academics like Tang Yi openly speculate that ‘the Christian faith may eventually conquer China and Christianize Chinese culture’ – though he thinks it more likely either that ‘Christianity may eventually be absorbed by Chinese culture, following the example of Buddhism … and become a sinless religion of the Chinese genre’ or that ‘Christianity [will] retain its basic Western characteristics and settle down to be a sub-cultural minority religion.’81

After much hesitation, at least some of China’s communist leaders now appear to recognize Christianity as one of the West’s greatest sources of strength.82 According to one scholar from the Chinese Academy of the Social Sciences:

We were asked to look into what accounted for the … pre-eminence of the West all over the world … At first, we thought it was because you had more powerful guns than we had. Then we thought it was because you had the best political system. Next we focused on your economic system. But in the past twenty years, we have realized that the heart of your culture is your religion: Christianity. That is why the West has been so powerful. The Christian moral foundation of social and cultural life was what made possible the emergence of capitalism and then the successful transition to democratic politics. We don’t have any doubt about this.83

Another academic, Zhuo Xinping, has identified the ‘Christian understanding of transcendence’ as having played ‘a very decisive role in people’s acceptance of pluralism in society and politics in the contemporary West’:

Only by accepting this understanding of transcendence as our criterion can we understand the real meaning of such concepts as freedom, human rights, tolerance, equality, justice, democracy, the rule of law, universality, and environmental protection.84

Yuan Zhiming, a Christian film-maker, agrees: ‘The most important thing, the core of Western civilization … is Christianity.’85 According to Professor Zhao Xiao, himself a convert, Christianity offers China a new ‘common moral foundation’ capable of reducing corruption, narrowing the gap between rich and poor, promoting philanthropy and even preventing pollution.86 ‘Economic viability requires a serious moral ethos,’ in the words of another scholar, ‘more than just hedonistic consumerism and dishonest strategy.’87 It is even said that, shortly before Jiang Zemin stepped down as China’s president and Communist Party leader, he told a gathering of high-ranking Party officials that, if he could issue one decree that he knew would be obeyed in China, it would be to ‘make Christianity the official religion of China’.88 In 2007 his successor Hu Jintao held an unprecedented Politburo ‘study session’ on religion, at which he told China’s twenty-five most powerful leaders that ‘the knowledge and strength of religious people must be mustered to build a prosperous society’. The XIVth Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party was presented with a report specifying three requirements for sustainable economic growth: property rights as a foundation, the law as a safeguard and morality as a support.

If that sounds familiar, it should. As we have seen, those used to be among the key foundations of Western civilization. Yet in recent years we in the West have seemed to lose our faith in them. Not only are the churches of Europe empty. We also seem to doubt the value of much of what developed in Europe after the Reformation. Capitalist competition has been disgraced by the recent financial crisis and the rampant greed of the bankers. Science is studied by too few of our children at school and university. Private property rights are repeatedly violated by governments that seem to have an insatiable appetite for taxing our incomes and our wealth and wasting a large portion of the proceeds. Empire has become a dirty word, despite the benefits conferred on the rest of the world by the European imperialists. All we risk being left with are a vacuous consumer society and a culture of relativism – a culture that says any theory or opinion, no matter how outlandish, is just as good as whatever it was we used to believe in.

Contrary to popular belief, Chesterton did not say: ‘The trouble with atheism is that when men stop believing in God, they don’t believe in nothing. They believe in anything.’ But he has Father Brown say something very like it in ‘The Miracle of Moon Crescent’:

You all swore you were hard-shelled materialists; and as a matter of fact you were all balanced on the very edge of belief – of belief in almost anything. There are thousands balanced on it today; but it’s a sharp, uncomfortable edge to sit on. You won’t rest until you believe something.89

To understand the difference between belief and unbelief, consider the conversation between Muktar Said Ibrahim, one of the Islamists whose plot to detonate bombs in the London transport system was discovered in 2005, and a former neighbour of his in Stanmore, a suburb in the northern outskirts of London. Born in Eritrea, Ibrahim had moved to Britain at the age of fourteen and had just been granted UK citizenship, despite a conviction and prison sentence for his involvement in an armed robbery. ‘He asked me’, Sarah Scott recalled, ‘if I was Catholic because I have Irish family. I said I didn’t believe in anything and he said I should. He told me he was going to have all these virgins when he got to Heaven if he praises Allah. He said if you pray to Allah and if you have been loyal to Allah you would get 80 virgins, or something like that.’ It is the easiest thing in the world to ridicule the notion, apparently a commonplace among jihadis, that this is the reward for blowing up infidels. But is it significantly stranger to believe, like Sarah Scott, in nothing at all? Her recollected conversation with Ibrahim is fascinating precisely because it illuminates the gulf that now exists in Western Europe between a minority of fanatics and a majority of atheists. ‘He said’, Scott recalled after her former neighbour’s arrest, ‘people were afraid of religion and people should not be afraid.’90

What Chesterton feared was that, if Christianity declined in Britain, ‘superstition’ would ‘drown all your old rationalism and scepticism’. From aromatherapy to Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, the West today is indeed awash with post-modern cults, none of which offers anything remotely as economically invigorating or socially cohesive as the old Protestant ethic. Worse, this spiritual vacuum leaves West European societies vulnerable to the sinister ambitions of a minority of people who do have religious faith – as well as the political ambition to expand the power and influence of that faith in their adopted countries. That the struggle between radical Islam and Western civilization can be caricatured as ‘Jihad vs McWorld’ speaks volumes.91 In reality, the core values of Western civilization are directly threatened by the brand of Islam espoused by terrorists like Muktar Said Ibrahim, derived as it is from the teachings of the nineteenth-century Wahhabist Sayyid Jamal al-Din and the Muslim Brotherhood leaders Hassan al-Banna and Sayyid Qutb.92 The separation of church and state, the scientific method, the rule of law and the very idea of a free society – including relatively recent Western principles like the equality of the sexes and the legality of homosexual acts – all these things are openly repudiated by the Islamists.

Estimates of the Muslim population of West European countries vary widely. According to one estimate the total population has risen from around 10 million in 1990 to 17 million in 2010.93 As a share of national populations, Muslim communities range in size from as much as 9.8 per cent in France to as little as 0.2 per cent in Portugal.94 Such figures seem to belie the warnings of some scholars of a future ‘Eurabia’ – a continent Islamicized by the end of the twenty-first century. However, if the Muslim population of the UK were to continue growing at an annual rate of 6.7 per cent (as it did between 2004 and 2008), its share of the total UK population would rise from just under 4 per cent in 2008 to 8 per cent in 2020, to 15 per cent in 2030 and to 28 per cent in 2040, finally passing 50 per cent in 2050.95

Mass immigration is not necessarily the solvent of a civilization, if the migrants embrace, and are encouraged to embrace, the values of the civilization to which they are moving. But in cases where immigrant communities are not successfully assimilated and then become prey to radical ideologues, the consequences can be profoundly destabilizing.96 The crucial thing is not sheer numbers so much as the extent to which some Muslim communities have been penetrated by Islamist organizations like the Arab Muslim Brotherhood, the Pakistani Jama’at-i Islami, the Saudi-financed Muslim World League and the World Assembly of Muslim Youth. In Britain, to take perhaps the most troubling example, there is an active Muslim Brotherhood offshoot called the Muslim Association of Britain, two Jama’at-i Islami spin-offs, the Islamic Society of Britain and its youth wing, Young Muslims UK, as well as an organization called Hizb ut-Tahrir (‘Party of Liberation’). Hizb ut-Tahrir openly proclaims its intention to make ‘Britain … an Islamic state by the year 2020!’97 Also known to be active in recruiting terrorists are al-Qaeda and the equally dangerous Harakat ul-Mujahideen. Such infiltration is by no means unique to the UK.*

The case of Shehzad Tanweer illustrates how insidious the process of radicalization is. Tanweer was one of the suicide bombers who wreaked havoc in London on 7 July 2005, detonating a bomb aboard a Circle Line Underground train between Aldgate and Liverpool Street that killed himself and six other passengers. Born in Yorkshire in 1983, Tanweer was not poor; his father, an immigrant from Pakistan, had built up a successful takeaway food business, selling fish and chips and driving a Mercedes. He was not uneducated, in so far as a degree in sports science from Leeds Metropolitan University counts as education. His case suggests that no amount of economic, educational and recreational opportunity can prevent the son of a Muslim immigrant from being converted into a fanatic and a terrorist if the wrong people get to him. In this regard, a crucial role is being played at universities and elsewhere by Islamic ‘centres’, some of which are little more than recruiting agencies for jihad. Often, such centres act as gateways to training camps in countries like Pakistan, where the new recruits from bilad al-kufr (the lands of unbelief) are sent for more practical forms of indoctrination. Between 1999 and 2009 a total of 119 individuals were found guilty of Islamism-related terrorist offences in the UK, more than two-thirds of them British nationals. Just under a third had attended an institute of higher education, and about the same proportion had attended a terrorist training camp.98 It has been as much through luck as through effective counter-terrorism that other attacks by British-based jihadis have been thwarted, notably the plot in August 2006 by a group of young British Muslims to detonate home-made bombs aboard multiple transatlantic planes, and the attempt by a Nigerian-born graduate of University College London to detonate plastic explosive concealed in his underwear as his flight from Amsterdam was nearing Detroit airport on Christmas Day 2009.

In his Decline and Fall, Gibbon covered more than 1,400 years of history, from 180 to 1590. This was history over the very long run, in which the causes of decline ranged from the personality disorders of individual emperors to the power of the Praetorian Guard and the rise of monotheism. After the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180, civil war became a recurring problem, as aspiring emperors competed for the spoils of supreme power. By the fourth century, barbarian invasions or migrations were well under way and only intensified as the Huns moved west. Meanwhile, the challenge posed by Sassanid Persia to the Eastern Roman Empire was steadily growing. The first time Western civilization crashed, as Gibbon tells the story, it was a very slow burn.

But what if political strife, barbarian migration and imperial rivalry were all just integral features of late antiquity – signs of normality, rather than harbingers of distant doom? Through this lens, Rome’s fall was in fact quite sudden and dramatic. The final breakdown in the Western Roman Empire began in 406, when Germanic invaders poured across the Rhine into Gaul and then Italy. Rome itself was sacked by the Goths in 410. Co-opted by an enfeebled emperor, the Goths then fought the Vandals for control of Spain, but this merely shifted the problem south. Between 429 and 439, Genseric led the Vandals to victory after victory in North Africa, culminating in the fall of Carthage. Rome lost its southern Mediterranean breadbasket and, along with it, a huge source of tax revenue. Roman soldiers were barely able to defeat Attila’s Huns as they swept west from the Balkans. By 452, the Western Roman Empire had lost all of Britain, most of Spain, the richest provinces of North Africa, and south-western and south-eastern Gaul. Not much was left besides Italy. Basiliscus, brother-in-law of Emperor Leo I, tried and failed to recapture Carthage in 468. Byzantium lived on, but the Western Roman Empire was dead. By 476, Rome was the fiefdom of Odoacer, King of the Scirii.99