9

Let's Innovate

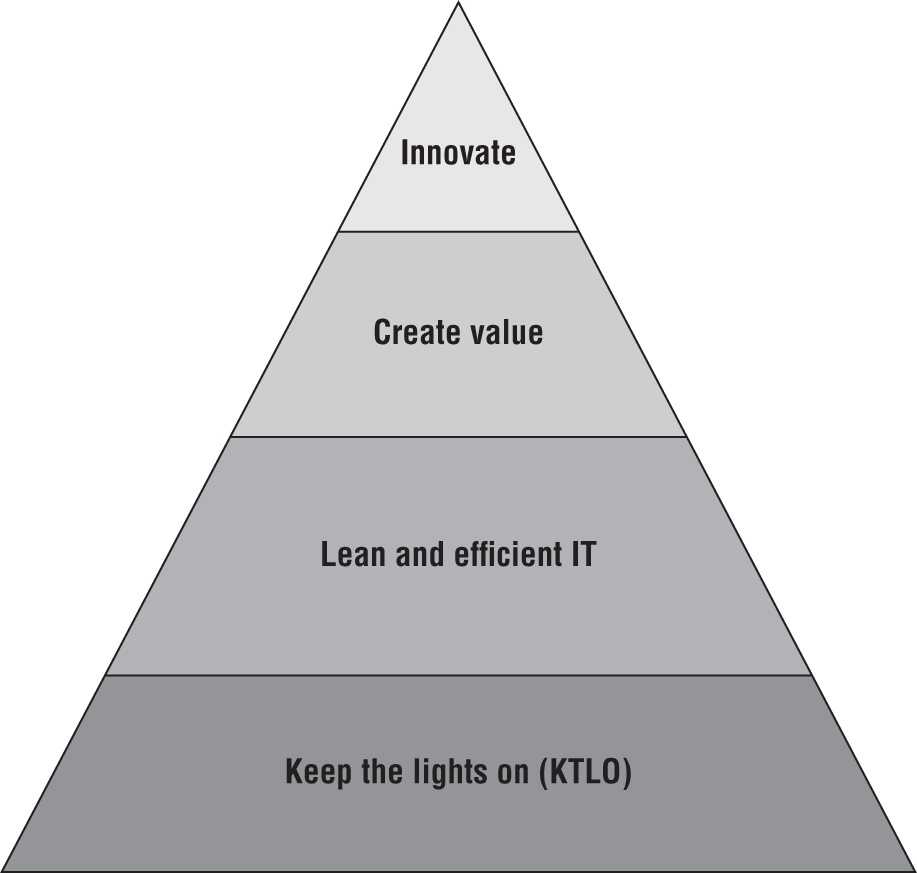

To successfully innovate, organizations first need to achieve the bottom three steps of the Laudato Hierarchy of IT Needs: keep the lights on (KTLO), operate a lean and efficient IT Department, and create value for your business.

To foster innovation, you need stable and affordable systems, a process to prioritize projects, and a method to deliver those projects successfully. When IT is a well-oiled machine, it is ripe for innovation, and giant leaps forward will occur. Welcome to the top of the pyramid. As shown in Figure 9.1, it’s time to innovate!

Figure 9.1 Laudato Hierarchy of IT Needs

© 2017 Andrew Laudato All Rights Reserved Hierarchy of IT Needs

In 2010, we implemented point-of-sale email receipts at Pier 1 Imports. I was quite excited, and at dinner that night, I bragged about it to my teenage daughter. She looked at me and said, “You didn't already have that?” Clearly, she was not impressed. Omni-channel capabilities like buy online, pickup in store (BOPUS), curbside pickup, ship-from-store, and universal returns don't impress anyone these days. In healthcare, online records, electronic scheduling, and telemedicine are the new norm. Yesterday's innovations are today's expectations.

To invest in innovation successfully, you must be willing to develop an innovator’s mindset, dedicate resources, and embrace risk. Only then can you move on to generate ideas, prototype, and turn your vision into reality.

Develop the Mindset

In most companies, especially large ones, a return on investment (ROI) calculation is performed before a project is undertaken. Risks are documented, and contingency plans are drawn up. A project is treated as an investment, and a solid return on the money is expected. Sure, there are consequences for failure: When a project fails, people lose their credibility, their funding, and sometimes even their jobs. However, if you want to be an innovator, you must take calculated risks. When you're able to consider a failed project a valuable learning experience, you have developed an innovator's mindset.

Dedicate Resources

Companies don't innovate; people do. For innovation to work, the company must create a nurturing environment. Sticking a group of people in a room and telling them to innovate is no better than putting a seed on a concrete floor and telling it to grow.

What if you took your best and brightest people away from their day jobs and had them focus 100% on innovation? To even approach this discussion, you must have an extremely reliable infrastructure, a well-managed IT budget, and a steady stream of value creation. In other words, before a CIO can ask the CEO to allocate people and money for a high-risk venture, things better be operating smoothly. On the other hand, if you can only spare the new person and a few interns, your innovation will fizzle. When you're overly reliant on a guy named Brent7 to keep your systems running, there's no chance he can be assigned to an innovation project.

Embrace Risk

Innovation doesn't exist without risk-taking. If you truly expect to innovate—and to thrive, you better innovate—you must embrace the idea that many of the initiatives you support, fund, and advocate for will be abject failures.

This goes back to the Laudato Hierarchy of IT Needs pyramid: when your foundation is solid, your IT costs are low, and your team is constantly delivering value, you have earned the right to take risks. When taking on a high-risk endeavor, be clear that there is a good chance it may not work. Be confident that the upside is worth the risk, and only gamble with the amount of money you can afford to lose.

When you examine today's most successful companies, you can easily correlate their results with their willingness to embrace risk.

Idea Generation

When you're in a good place to innovate, you need to generate ideas. Here are some thought starters on the best places to find ideas:

- Talk to your front-line employees. The employees who deal directly with the customers understand the customer best. Sharon Leite, CEO at Vitamin Shoppe, holds roundtable discussions with store, distribution center, and corporate employees. This keeps Sharon close to the team—and she receives direct insights into what customers are asking for. Innovation is a key pillar at Vitamin Shoppe; it's built into our DNA.

- Survey your customers and ask them about their problems and frustrations. Innovation is problem-solving for consumers.

- Look to other industries: Reed Hastings, the founder of Netflix, was inspired by the gym membership business model before he built the subscription-based DVD business.

- Talk with analysts and thought leaders. They have insight into the trends that are receiving traction with early adopters across various sectors and industries.

- Partner with start-ups. They have good ideas; you have the resources to execute and scale. It's a potential perfect synergy between large and small companies.

- Partner with universities. Students and professors have the knowledge, research skills, and capacity to be terrific innovation partners.

Rapid Prototyping

The mantra of the start-up founder is fail fast. This term may sound confusing, because nobody wants to fail, and certainly nobody wants to fail quickly. However, founders understand that to accomplish something truly innovative, they must take risks. They also know that not every idea will be successful, and the quicker they can learn which ideas won't work, the faster they can learn from the failure, iterate, and try the next idea. Failing fast minimizes the time, money, and resources spent on bad ideas.

To accomplish failing fast or, hopefully, succeeding fast, use a prototype. A prototype is a mockup or partially working sample of the final product. I once worked with a business analyst who mocked up an entire business intelligence dashboard in Microsoft PowerPoint slides. To test the concept, we pretend clicked on buttons and then flipped to the page in the slide deck that the actual application would go to when it was completed. This desktop simulation was a quick way to test and iterate the concept before it was built. As an added benefit, the prototype served as a business requirement document for the development team.

The next step in our rapid-prototyping process was to have the development team build a working prototype in HTML. This was still a mockup, but the next step had actual users try the application on a computer. The computer mockup generated more changes, and the process was repeated until an acceptable design was found. If the business intelligence dashboard was a failure, it would be identified during prototyping, preventing us from wasting money on development.

The final step in our rapid prototyping was to build a beta version of the final product: more real than paper and HTML, but still not a full-fledged application. The beta product was released to a limited group of users, monitored, and updated as necessary.

Rapid prototyping ensures the product meets the needs of the customer even if the customer isn't exactly sure what they want in the early stages of the project. In the next chapter, we'll examine how to use these principles to evaluate your IT Department.

Note

- 7. Brent is a character in The Phoenix Project: A Novel About IT, DevOps, and Helping Your Business Win by Gene Kim, Kevin Behr, and George Spafford (IT Revolution Press, 2013),

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/17255186-the-phoenix-project.