18

The Distance Runner’s Diet

Fuel Your Body with the Proper Foods

Can better nutrition create better athletes? When I asked that question some years ago of Ann C. Grandjean, EdD, director of the International Center for Sports Nutrition in Omaha, Nebraska, she offered a one-word answer: “Genetics!” What Dr. Grandjean meant was that great athletes are born with the ability to succeed, a gift of good genes that allows them—when properly trained and fed—to run and jump and throw faster and higher and farther than their less genetically gifted opponents. In suggesting better nutrition for long-distance runners, she knew that sports nutritionists cannot promise you success—but at least you will not fail because of poor nutrition and not be left wondering how much better you could be.

How important is good nutrition? Frederick C. Hagerman, PhD, of Ohio University in Athens, led off a conference in Columbus, Ohio, on nutrition for the marathon and other endurance sports prior to the men’s Olympic marathon trials by saying that the second most important question asked by athletes is “What should I eat to make me stronger, better, and faster for my sport?” (The most important question, he said, is “How do I train?”) Dr. Hagerman claimed that too many athletes had no idea how to eat properly to maximize their performance. These athletes also failed to realize that performance actually starts with the stomach, not with training.

There are three important areas of the distance runner’s diet. One is overall nutrition, the ability to maintain high energy levels during training. The second is prerace nutrition, what you eat in the last few days before running to ensure a good performance. Third is what you consume before and during the race itself to make sure that you maximize performance—and get to the finish line on your own two feet. This chapter covers the first two, training nutrition and prerace nutrition. Your body’s needs during the race are covered in Chapter 21, “Drinking on the Run.”

THE RIGHT FUEL

Let’s talk about why diet (i.e., finding the right fuel) is so important to your performance, not to mention your health. When you run long distances, your energy requirements increase. In an article on endurance exercise in the journal The Physician and Sportsmedicine, authors Walter R. Frontera, MD, and Richard P. Adams, PhD, said, “During sustained exercise such as marathon running, total body energy requirements increase 10 to 20 times above resting values.” Runners need to eat more of the proper foods to fuel their muscles. They also need to drink more, particularly in warm weather.

At a sports nutrition conference in Columbus, Linda Houtkooper, PhD, a registered dietitian at the University of Arizona at Tucson, made it clear that endurance athletes in particular should get most of their calories from carbohydrates, preferably wholesome fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

Carbs have been recognized as the preferred fuel for the endurance athlete because they are easy to digest and easy to convert into energy. Carbohydrates convert quickly into glucose (a form of sugar that circulates in the blood) and glycogen (the form of glucose stored in muscle tissue and the liver). Proteins can convert into glucose/glycogen, but at a greater energy cost. Fats can get easily stored as body fat. The body can normally store about 2,000 calories’ worth of carbohydrate (glycogen) in the muscle, enough for maybe 20 miles of running.

No argument there. The only problem is that with 35,000 items in the supermarket, marathon runners sometimes need help determining which foods are highest in quality carbohydrates (as opposed to refined sugar). Unless you plan to eat spaghetti three meals a day (and even pasta contains 13 percent protein and 4 percent fat), you may need to start reading labels.

Dr. Houtkooper explained that the body requires at least forty nutrients that are classified into six nutritional components: proteins, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water. “These nutrients cannot be made in the body and so must be supplied from solid or liquid foods,” she says. Plus, food contains a myriad of phytochemicals and other bioactive compounds that promote good health. She listed six categories that form the fundamentals of a nutritionally adequate food selection plan (in descending order of importance): fruits, vegetables, grains, lean meats/legumes/nuts, low-fat milk products, and fats/sweets.

The recommendations for a healthy diet suggest that carbohydrates (55 percent) should be the foundation of each meal, with some protein (15 percent) as the accompaniment and a little bit of healthy fat (30 percent) to add flavor and satiety. That is the gold standard and one that I offer to runners asking me questions online about nutrition. But all carbohydrates are not created alike. There are simple and complex carbs, sugars, and starches; refined and unprocessed carbs; “good carbs” and “bad carbs.” The topic is very complex.

Refined carbs include sugar, honey, jam, sweets, and soft drinks. Nutritionists recommend that refined, simple sugars make up only 10 percent of your diet because they are nutrient poor, offering minimal vitamins and minerals. You want to concentrate your diet on wholesome “quality carbohydrates” from fruits, vegetables, whole-grain bread and pasta, and beans/legumes.

Endurance athletes in particular benefit from a carbohydrate-rich plant-based diet because of the muscle glycogen they burn each day that needs to be replenished. You need to aim for more total carbohydrates than people who fail to exercise. You can eat (in fact, may need to eat) more total calories without experiencing weight gain. The average male runner training for a marathon and running 25 to 30 miles a week probably needs a daily caloric intake near 3,000 to maintain muscle glycogen stores. As your mileage climbs beyond that, you need to eat more and more food, not less. In all honesty, this is why a lot of runners run and why they train for marathons. Their common motto is “I love to eat.” But a word of caution: Some runners are “sedentary athletes.” They may run hard for an hour, then sit the rest of the day. They may fail to burn as many calories as they think they do; then they overeat and end up gaining weight.

THE DISASTER DIET

The ageless Atkins diet and various other low-carb fad diets (like paleo or ketogenic) offer little more than a trap for distance runners. This is true of almost any weight-loss diet that limits carbohydrate intake. Go on one of these fad diets and you may experience a sudden reduction in weight, as measured by your bathroom scale. This weight loss, often dramatic, provides an instant boost to the dieter’s ego and may cause the individual to stay on the diet and continue to lose weight. That is good. But the instant loss is artificial, since the shift in the protein/carbohydrate ratio causes the body to lose fluids.

For each 1 ounce of carbs the body stores as glycogen, the body also stores about 3 ounces of water. When you deplete those carbs, you lose water weight. That is not the greatest prerace strategy, since dehydration can be a danger for those training for a marathon, and particularly during the marathon itself. Add to that the discomfort caused by constipation, a side effect of a low-carb diet, which typically contains an inadequate supply of fiber-rich fruits, veggies, and whole grains.

There are no magic diets when it comes to weight loss.

Someone who is clinically obese can easily lose 5 to 10 pounds within a few weeks simply through this process of dehydration. But that person will continue to lose weight and maintain that weight loss only if he or she restricts calorie intake. There are no magic diets when it comes to weight loss. It is calories in versus calories burned, and the weight-loss regimens that work best are those that create a small but sustainable calorie deficit. For example, one runner eliminated two cans of cola a day (300 calories) and lost 30 pounds in a year because of that simple, sustainable dietary change. Just cutting 100 calories a day theoretically leads to 10 pounds of fat loss a year in a runner who has excess fat to lose.

Some high-mileage athletes actually may need to supplement their diets with high-carbohydrate 100 percent fruit juices to ensure sufficient energy for their daily runs. But you also need more protein, says Liz Applegate, PhD, a professor at the University of California at Davis, and the author of Eat Smart, Play Hard. Dr. Applegate suggests that runners training for a marathon need a minimum of 70 grams of protein a day—more if you’re a high-mileage trainer. Most important, she advises, you need that protein distributed evenly throughout the day, including soon after you exercise, particularly after workouts longer than 10 miles.

“Eating a bagel or candy bar to quickly restore the calories you burned is not enough,” argues Dr. Applegate. “Better would be a chug of chocolate milk or a tuna sandwich and piece of fruit. For the recovery meal, you need to eat three to four times more calories of carbohydrates than of protein (a ratio of about 3 or 4 grams carbohydrate to 1 gram protein). The longer the run, and the sooner you plan to train again, the more important this becomes.” Following the 4-to-1 rule is particularly important after long runs. If you plan to use an energy bar before or after a long run, you need to read the label, says Dr. Applegate, since some bars contain mostly carbohydrates, while others may include large amounts of protein. You want a bar that offers both carbs and protein. The same goes for protein shakes. You want a fruit smoothie with some added protein; not just a low-carb, high-protein shake, Also note that recovery can start with your prerun meal. Hence, you want to eat carbs and protein both before and after you exercise.

CARBS RULE

Nevertheless, carbohydrates still rule. Serious runners may need about 3 to 4 grams of carbs per pound of ideal body weight. If you are a lean, mean 150 pounds, this comes to about 450 to 600 grams per day. Eating such a high-carbohydrate diet allows you to continuously restock your muscles with glycogen, the fuel that is as important in training as it is in racing. Because of the number of miles you run, you can also afford a somewhat higher ratio of simple versus complex carbohydrates in your diet—preferably in the form of 100 percent fruit juice and fresh fruit, though gummy bears and marshmallows will also fuel your muscles (minus the investment in good health).

Here is where I part company with the popular low-carb diets (Atkins, South Beach, the Zone, and so forth) that suggest food ratios near 40 percent carbohydrates, 30 percent protein, and 30 percent fat. Or the high-fat keto diet with less than 50 grams (200 calories) of carbs a day. People do lose weight following low-carb diets, although researchers suggest it is mainly because in following this regimen, they also cut calorie intake. On the other hand, plant-based diets, according to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, are a healthy option for athletes interested in eliminating meat from their daily meals. When it comes to losing weight, all nutritionists agree that the best approach is to combine diet and exercise, and eat just a little less to create a small but effective and sustainable calorie deficit. And even this may not be enough if dieting causes a metabolism slowdown.

FOODS RICH IN CARBOHYDRATES

The traditional prerace meal for marathoners is pasta. With a wife of Italian American origin, I reap the culinary benefits of a tradition that literally demands frequent doses of pasta. But spaghetti (or macaroni or other forms of pasta) every day can become boring, particularly when you’re trying to eat a carbohydrate-based diet every day to support your hard training. Fortunately, there are many foods you can eat to guarantee that your diet is high in carbohydrates, both during training and before races.

Nancy Clark’s Sports Nutrition Guidebook lists the following carbohydrate-rich foods.

FRUITS

Apples

Bananas

Dates

Dried apricots

Oranges

Raisins

VEGETABLES

Broccoli

Carrots

Green beans

Peas

Tomato sauce

Winter squash

GRAINS, LEGUMES, AND POTATOES

Baked (sweet) potato

Beans (pinto, kidney, garbanzo, etc.)

Corn

Hummus

Lentils

Pasta, all shapes

Quinoa

Rice

BREADS, ROLLS, AND CRACKERS

Bagels

Bran and corn muffins

English muffins

Graham crackers

Matzo

Pancakes

Pita, wraps

Pretzels

Waffles

Whole-grain breads and rolls

Popcorn

BREAKFAST CEREALS

Cream of wheat

Granola

Grape-Nuts

Muesli

Oatmeal

Raisin bran

BEVERAGES

Apple cider

Cran-raspberry juice

Flavored milk

Fruit smoothie

Orange juice

SWEETS, SNACKS, AND DESSERTS

Cranberry sauce

Fig bars

Fruit yogurt

Honey

Maple syrup

Strawberry jam

Clark warns that some foods that runners assume are high in carbohydrates may have a high percentage of calories hidden in fat. These foods include croissants, Ritz crackers, thin-crust pizza, and granola. When in doubt, Clark advises, read the labels.

Running can be an effective fat-burning exercise (though burning fat differs from losing body fat, which requires a calorie deficit). You will burn approximately 100 calories a mile if you weigh around 150 pounds. If you weigh more, you burn more, which I suppose may be one of the few benefits of carrying a few extra pounds when you run. Nevertheless, run 36 miles (3,600 calories burned) and you can theoretically lose a pound of fat—assuming you do not replace those calories with hefty postrun meals. Follow my marathon training program and you will run approximately 500 miles over a period of 18 weeks. Theoretically, at least, you can lose 15 pounds by training for a marathon. This assumes that you do not increase your calorie consumption to meet your body’s increased energy needs.

As your mileage climbs, you need to eat more and more food.

Some people seeking to finish their first marathon, however, are more than 15 pounds overweight—or they think they are—so they attempt to drop some additional pounds by dieting. To a certain extent, this is not a bad idea, assuming you choose your eating plan prudently. Those who follow a fad diet that lowers carbohydrate intake make a major mistake, because most of those programs fail to provide enough energy for endurance activities. Follow a low-carb diet, for example, and if you’re eating 3,000 calories a day, you’ll ingest much less than the 400 grams of carbohydrate recommended according to Dr. Applegate. “One problem,” she says, “is that individuals following a low-carb diet Monday to Thursday start running out of energy by the weekend, when they’re about to do their long run. They need to take a day off on Friday, not to rest from their running, but to rest from their diet. These low-carb runners either crash during the workout or binge on carbs to survive, which makes them feel guilty.”

The aspects of most low-carb diets that Dr. Applegate likes is their emphasis on low-carb fruits and veggies, such as berries and leafy green vegetables, and protein. She feels that runners who graze on too many refined carbs (pretzels, bagels, jelly beans) and entirely avoid meats and other protein sources are not doing themselves any favors.

You do not need to patronize Italian restaurants to ensure an adequate supply of complex carbohydrates. I sometimes choose a Chinese restaurant because rice is also high in carbs. And Nancy Clark points out that you can get plenty of carbs in most American restaurants. If you eat soup (such as minestrone, bean, rice, or noodle), potatoes, breads, and vegetables along with your main dish and maybe enjoy a piece of apple cobbler off the dessert tray, you can end up eating more carbohydrates than fats or protein.

Or take your cue from the Kenyans, whose typical diet is ugali, a type of cornmeal porridge, also known as obusuma, nshima, mielepap, phutu, or sadza depending on where you land on the African continent. My Italian relatives call the meal polenta, but regardless of regional name, ugali is very high in carbohydrates, which allows Kenyan runners to maintain a 70 percent high-carb diet, a number that most Westerners would find difficult to match.

PREMARATHON NUTRITION

Pasta has become the ritual prerace feast for marathoners. No major marathon is without its night-before spaghetti dinner, which has assumed almost ceremonial aspects.

The spaghetti dinner, of course, has more than a ceremonial purpose. We eat high-carbohydrate pasta to make sure our bodies have adequate glycogen, the fuel supply stored in the muscles that allows the most efficient form of energy metabolism. Although you could adapt to burning fat, fat metabolism requires more oxygen, and that limits performance when you are trying to surge up a hill or sprint to the finish line. The more glycogen you can store, the faster you can run for longer periods of time, because when muscle glycogen is depleted, muscles contract poorly. But a well-fueled athlete also needs a full supply of glycogen for the liver, a “processing station” that sends fuel through the bloodstream to the muscles and brain. So in addition to having your fuel tank to your hybrid car full, you need a fully charged battery. If you experience low blood sugar, your brain will lack fuel. You’ll have trouble concentrating and focusing on the task at hand and instead wish you had never started this adventure. Bad mood, bad performance.

Various diets have been devised in an attempt to ensure maximum glycogen storage. Entire books have been written on the subject of sports nutrition, but premarathon eating is not that difficult. Simply concentrate on eating your standard carb-based training diet, and taper your training the final days before the marathon. For most endurance athletes who do follow a plant-based diet rich in grains, fruits, and vegetables, carbo-loading requires minimal changes to your regular daily eating routine; the bigger changes are in your training routine. This is good because you do not want to subject your system to any radical shifts just when you are about to run 26 miles. By running less, you allow your muscles the time they need to replenish depleted glycogen stores.

If you are racing out of town, you may want to take along some snacks to eat between the pasta dinner and the race the next morning. Graham crackers, energy bars, and vanilla wafers can be particularly useful, especially if you are competing in a foreign country where you’re not accustomed to the food.

MEASURE YOUR FOODS

I do not spend a lot of time agonizing over what I eat, but on one occasion when a dietitian evaluated my diet, I averaged 12 percent protein, 19 percent fat, and 68 percent carbohydrates over a typical 3-day period. Fifty-two percent of my total calories came from complex carbohydrates, and 16 percent were from simple carbohydrates. (Dr. Applegate might argue that I was somewhat deficient in protein and a bit high on sweets, but I later corrected that in my diet.) A good target for most runners is about 55 percent to 65 percent carbs, 10 percent to 15 percent protein, and 20 percent to 30 percent fat. If you want to analyze your diet, use apps such as MyFitnessPal, LoseIt! or SparkPeople.com. When evaluating your daily food intake, be sure to serve yourself your normal portion and then measure the food accurately. That way you’ll get a true picture of what you are really eating.

The nutritional analysis of my diet also showed I was getting more than the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of vitamins and minerals, so I do not normally take supplements, not even a daily multivitamin, anymore. Also, my last cholesterol test indicated 154 total cholesterol, including 54 HDL (the good cholesterol), a very favorable ratio. If I have succeeded with my dietary goals, I believe there are two reasons: a healthy breakfast and Joanne Milkereit’s refrigerator.

1. A HEALTHY BREAKFAST

You can think of a good breakfast as a fast start out of the blocks. Most mornings, I drink an 8-ounce glass of orange juice mixed with cranberry juice and eat a high-fiber, whole-grain breakfast cereal with fat-free milk, piled high with raisins, bananas, and whatever other fruits are in season: strawberries, raspberries, blueberries. In Florida, I found a specialty grocery store (Fresh Market) that offers dried cranberries, a treat to which I have become addicted. A couple of times when we were out of milk, I substituted orange juice on my cereal. Yes, it sounds disgusting, but don’t knock it until you’ve tried it.

I used to add two slices of toast spread with margarine or butter, and sometimes a soft-boiled egg, although as my mileage totals declined, I began to cut back on my calorie consumption to maintain a steady weight. Now, since protein needs increase with aging, Nancy Clark suggests I add eggs (or Greek yogurt or cottage cheese), given the lack of protein in my breakfast.

Sometimes on Sundays, between my long run and church, my wife and I will treat ourselves to a special breakfast with coffee cake (or pancakes, waffles, or French toast), bacon, and scrambled eggs with mozzarella cheese. Research suggests that if you are going to do any “fun” eating of high-fat foods, it is best to do it on days when you burn a lot of calories and can quickly metabolize those foods. This fits Clark’s mantra that a diet can be 90 percent “quality foods” and 10 percent “stuff,” if desired. (Nancy has been known to offer chocolate cake dispensations for important family events, such as birthdays.)

2. JOANNE MILKEREIT’S REFRIGERATOR

Let me tell you about Joanne Milkereit’s refrigerator. Joanne Milkereit, RD, was the nutritionist at the Hyde Park Co-Op, an upscale grocery store near the University of Chicago, when we collaborated to write Runner’s Cookbook back in 1979.

While we were working on the cookbook, Milkereit told me that all runners should tape the following words on their refrigerators: Eat a wide variety of lightly processed foods. Go back and reread that. Think about it. By wide variety, she means you sample all the food groups. Milkereit says: “When you eat ‘lightly processed,’ not only do you get all the vitamins and minerals but you get the fiber in plant foods.” It is amazing that after all the nutritional research done in the past century, those words of advice remain valid.

What does Milkereit mean by lightly processed? Beware of foods that come wrapped in plastic or that you can buy at a fast-food restaurant—although restaurants have begun to offer such fare as low-fat burgers, carrot sticks, and nutritious salads. “Frankly,” says Milkereit, “I feel we sometimes dump on fast-food restaurants too much. There are good choices in fast-food restaurants and bad choices in other restaurants.”

Fad diets offer little more than a trap for distance runners.

Another food rule comes from Pete Pfitzinger, a 1984 and 1988 Olympic marathoner. He once told me, “I don’t put anything in my mouth that’s been invented in the last 25 years.” That may be a bit extreme, Pete, but if you pay attention to these two messages—you eat primarily “real” foods; preferably, locally grown—you probably cannot go too wrong with your diet.

Judy Tillapaugh, RD, of Fort Wayne, Indiana, believes that although runners understand the value of carbo-loading before a marathon, they do not give equal attention to day-to-day meal plans. “Endurance athletes need to continually replace energy stores with a diet high in nutrient-dense carbohydrates, low in fat, and with enough protein to maintain muscle,” says Tillapaugh. “Some weight-conscious runners don’t eat enough.” Clark agrees: “You can compete at your best only if you can train at your best. You can train at your best only if you fuel wisely and well on a day-to-day basis.”

And you need to spread your calories throughout the day by snacking, choosing healthy fare such as fruit, graham crackers, yogurt, or whole-grain bagels. If you need 3,500 calories daily, you can’t pack them into one or two meals. Athletes often neglect breakfast, then wonder why they are tired while running in the evening.

Fancy supplements, legal or illegal, cannot substitute for good nutrition. Excessive intake of vitamins is a waste of money and, in the case of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K), raises a possible threat of long-term health problems. Dr. Applegate suggests taking a multivitamin that contains iron and zinc every other day as a minimum dosage. “Younger women need more iron than postmenopausal women,” she says, “as do men who don’t eat meat.”

Eating a small 3-ounce portion of lean red meat two to four times a week can do a lot to make vitamin and mineral supplementation unnecessary; so can eating oily fish twice a week. I do both.

Eat a wide variety of lightly processed foods.

Can certain supplements improve performance? Apparently they can, judging from all the effort that goes into detecting their use by athletes competing at the Olympic level and in most professional sports. Drug use seems endemic in many sports, but in reality, probably only a relatively small percentage of athletes still try to steal an edge by using steroids or other performance-boosting drugs. Testing at major events and also outside competition is designed not only to catch cheaters for the benefit of drug-free athletes but also to prevent them from making mistakes that may shorten their life-spans.

I worry also about drug use by more ordinary athletes, those in the middle of the pack, who might be tempted to cut corners to set a PR or achieve a BQ. Nobody is testing this group, so who knows what negative behavior patterns exist?

LAST-MINUTE LOADING

Carbo-loading should not start or stop with the pasta dinner; scientists tell us it should continue throughout daily training routine and to the starting line to ensure maximum prerace nutrition. What you eat the day before the race fuels your muscles. What you eat the day of the race feeds the brain and tops off the muscles, too. W. Michael Sherman, PhD, an exercise scientist and sports nutrition expert from Ohio State University, tested trained cyclists pedaling indoors, feeding them 5 grams of carbohydrates per kilogram of body weight (2.25 g carb/pound) 3 hours before exercising. Both power and endurance increased when the athletes ate before exercising. (For a 165-pound cyclist, that would be about 1,500 calories from carbohydrate, the amount in twelve bagels or seven baked potatoes.) Dr. Sherman explains: “The cyclists were able to maintain a higher output for a longer period of time before fatiguing.”

Other studies have shown improved performance 4 hours after eating. “We can safely say that if you have a carbohydrate feeding 3 to 4 hours before a marathon, you can enhance performance,” says Dr. Sherman.

Admittedly, marathoners do not tolerate solids in their stomachs as well as cyclists do. Dr. Sherman suggests that runners either delay eating their prerace pasta until late evening or rise early for a carbohydrate-rich breakfast, such as oatmeal with raisins, or toast with honey, plus a glass of orange juice—foods that are tried-and-true, that you have eaten before your long training runs. If the fear of undesired pit stops requires you to abstain from fuel shortly before the event, sports nutritionist Nancy Clark suggests eating your breakfast the night before the marathon, right before you go to bed. This food will help maintain a normal blood sugar level, as well as your ability to think clearly and enjoy the race.

Liquid meals featuring high-carbohydrate drinks may work best for races near dawn. Dr. Sherman warns, however, that runners should try this first in practice or before minor races. You may find that if you consume too much immediately before the race, you waste time standing in portable-toilet lines both before and during the marathon.

Actually, practice may help you adjust to a different type of prerace nutrition that you may not have thought possible, including solid food an hour before the race. “You can train your body to do almost anything,” says Tillapaugh, who says her favorite snack before races is a bagel or low-fat crackers.

“The main thing is not to do anything out of the ordinary,” says Ed Eyestone, a 1988 and 1992 Olympic marathoner. “Yet you have to be flexible enough to go with the flow and eat what’s available. If you’re programmed to eat pancakes precisely 7 hours before a marathon, you may be disappointed.”

Experience has taught me that eating as close as 3 hours before a race gives my stomach sufficient time to digest the food and allows me to clear my intestines without the fear of having to duck into the bushes at the 5-mile mark. Closer to race time than that, however, and I’m asking for trouble. Timing can be a problem when running a race like the Honolulu Marathon, with its predawn start. But I have gotten up as early as 2:30 a.m. to eat breakfast before that race, and I notice I am not always alone in the hotel coffee shop.

I will order orange juice, toast or maybe a Danish, and/or some applesauce, along with a single cup of coffee to help clear my bowels. We now know that caffeine, once thought to have a diuretic effect, does not contribute to dehydration. But it does contribute to enhanced stamina and endurance.

If you are running an international race—and I have run marathons in Berlin, Athens, Rome, Melbourne, and other major cities—you may not be able to get a typical American breakfast, but the continental breakfast of coffee and rolls (with or without jelly) works quite well.

If the coffee shop does not open early enough, those snacks in the suitcase may come in handy. I am even less fussy. Practically every hotel has a soft drink machine on each floor, and frequently a can of pop is my last meal before a morning marathon.

I stop drinking 2 hours before the race, as it takes approximately that long for liquids to migrate from your mouth to your bladder. Another cup or two just before the start will help you tank up for the race, and this liquid will most likely be used before it reaches your bladder. If you drink too much in that 2-hour period, however, you may find yourself worrying about how you will relieve yourself several miles into the race.

Following his bronze medal performance at the 1991 World Championships, Steve Spence told Runner’s World that he drank so much that he had to urinate three times during the race without breaking stride. Personally, I prefer to avoid that. Experience teaches you how.

NO TREATS?

Does following a good sports diet mean no treats? My measured intake of 16 percent of calories from simple carbohydrates might be considered high for “healthy” people but not necessarily for a competitive runner. “Athletes are told to avoid junk foods,” says Dr. Grandjean, “but the reality is that if you are eating 4,000 calories a day, once you have taken in those first 2,000 calories—assuming you’ve done a reasonably intelligent job of selecting foods—you’ve probably obtained all the nutrients you need. You don’t need to worry about vitamins and minerals because you’ve already supplied your needs. You can afford foods high in sugar, so-called empty calories, because you just need energy. Your problem sometimes is finding enough time to eat.” And yet, fueling your body with primarily premium nutrition is an investment in optimal health, Clark reminds us.

“You can compete at your best only if you can train at your best.”

Sports nutrition thus comes down to time management.

The importance of general daily nutrition—as opposed to prerace nutrition—is that you need adequate energy for training and adequate nutrients to stay healthy plus heal the micro-injuries that occur during hard training sessions. And unlike the general population, you may need to eat more to help maintain your weight. If you are a 150-pound person running 30 miles a week to prepare for a marathon, you need approximately 3,000 calories a week more than if not running—assuming you maintain the same level of activity throughout the rest of your day. All too often, runners compensate for their “morning workout” by conserving energy the rest of the day. That is why some runners are unable to eat as much as they would like to be able to consume (without gaining weight, that is).

Most of those calories burned during exercise should be replaced with grains, fruits, and vegetables. Since those types of carbohydrates are bulkier than sugar, fats, or protein, the sheer volume of food that high-mileage runners must eat can become a problem.

Dr. Grandjean says that among the athletes she advises, distance runners are most knowledgeable about nutrition because their energy needs are so high. And those most talented, the ones already on top, often have the best nutrition. Fred Brouns of the Nutrition Research Center at the University of Limburg in the Netherlands studied cyclists competing in the Tour de France, both in the laboratory and during the race. He discovered that cyclists who finished near the front were those who were most successful at managing their diet. “Endurance athletes must pay close attention to food intake if they expect to keep energy levels high,” says Brouns.

“If you have a carbohydrate feeding 3 to 4 hours before a marathon, you can enhance performance.”

In the Tour de France, cyclists frequently burn 5,000 calories a day! There is no way these competitors can ride 5 or 6 hours a day and have time to eat that much, so they take many of their calories in liquid form while riding. Although most runners do not have anywhere near the energy requirements of a Tour cyclist, some high-mileage runners like to use high-carbohydrate drinks as a dietary supplement.

Nancy Ditz, the top U.S. finisher at the 1987 World Championships and 1988 Olympic marathons, took an intelligent approach to diet. Between those two marathons, Ditz decided she wanted to leave nothing to chance when it came to race preparation. Following the suggestion of her coach, Rod Dixon (the 1983 New York City Marathon champion and Olympic runner from New Zealand), she sought nutritional advice from Jerry Attaway, an assistant coach with the San Francisco 49ers. Attaway managed the team’s strength training, rehabilitation, and diet programs. He determined that based on Ditz’s energy expenditure while training 100 miles a week, she needed a higher percentage of carbohydrates than she was getting.

“Even though I was eating a pretty good diet, my carbohydrate intake still wasn’t enough,” Ditz recalls. She started using Exceed, a high-carbohydrate drink. (Such drinks are most effective when consumed immediately after exercise, when they can be most quickly absorbed.) Her calcium intake needed to be higher, so she also started drinking buttermilk with meals. Today’s runners simply enjoy a tall glass of low-fat chocolate milk to help them get the carbs, protein, and calcium they desire.

Ditz feared Attaway might ask her to cut out one of her favorite treats—cinnamon rolls at breakfast—but instead he eliminated mayonnaise on her sandwich at lunch. “That was a minor behavioral change for a major change in my ratio of fat to carbohydrate,” she says. (In 2 tablespoons of mayonnaise, you get 200 calories that are 100 percent fat!)

Attaway identified foods that did the most damage to Ditz’s diet, then asked, “Which do you really like?” He let her keep those, then eliminated the rest.

Ideally, long-distance runners interested in maximizing their performance in the marathon should find a knowledgeable sports dietitian to teach them how to eat. If I had to offer a single piece of dietary advice to every person who reads this book—regardless of whether you have Olympic aspirations—it would be to consult a dietitian. That RD behind the name of a sports consultant can be the major portal to better performance and good health. The referral network of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (eatright.org) can help you find a sports nutritionist. For a board-certified specialist in sports dietetics (CSSD), use the referral network at scandpg.org. Have that dietitian analyze your diet and recommend when, why, and what to eat for optimal performance.

DIET CHOICES

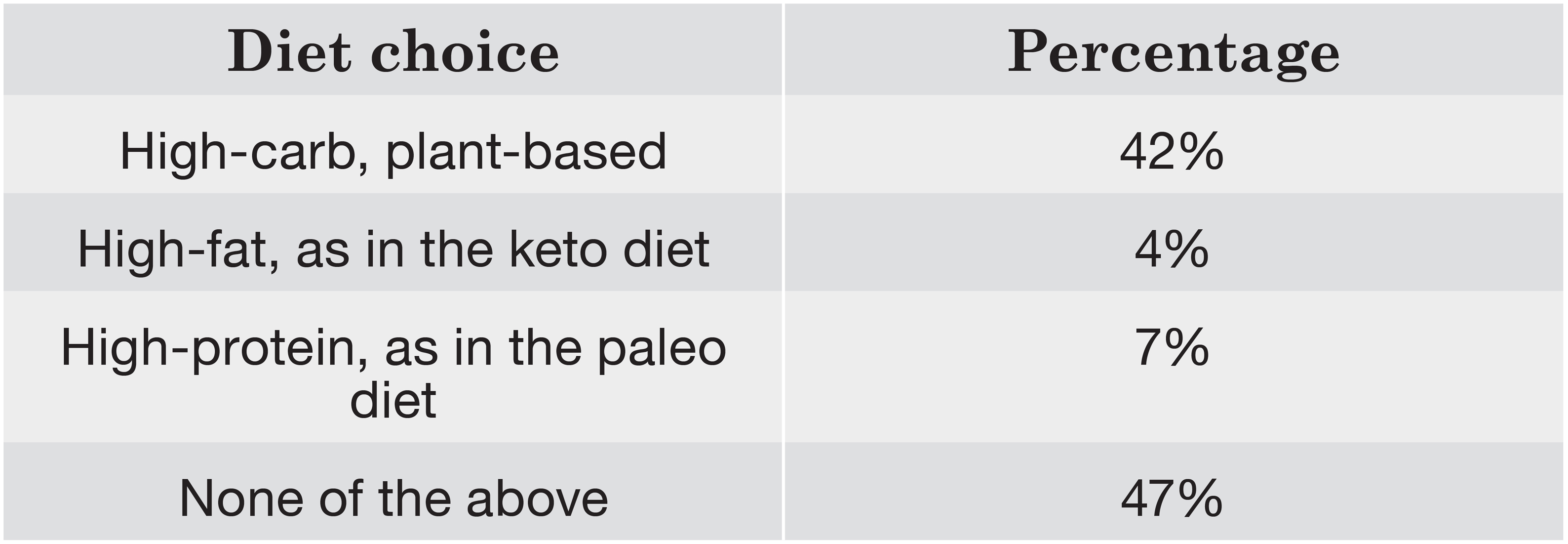

Do runners believe me when I tell them to follow a diet that is high in carbohydrates? More to the point, do they believe Nancy Clark, RD, author of the bestselling Nancy Clark’s Sports Nutrition Guide? I asked Nancy to join me in conducting a survey on Twitter. We asked her Twitter followers what diet they use to fuel their workouts: Plants? Meats? Fats? Here is what we learned.

Encouraging was the fact that neither the keto diet nor the paleo diet gained much traction among Clark’s followers. Carbs ruled the day—except nearly half of those who took the survey admitted they followed no particular diet! Obviously, we have some educating to do.

The advice offered in this chapter should help you get to the starting line ready to perform. In a later chapter I will offer more nutritional information on what to drink and eat between that starting line and the finish line at mile 26.2.