24

BQ

Boston Remains the Ultimate Goal for Many Runners

One huge standard of achievement is running fast enough to qualify for the Boston Marathon, the granddaddy of American marathons. For three-quarters of a century, the Boston Marathon accepted almost anyone who showed up at Hopkinton Gym on race day with a $1 entry fee in hand. You did not yet need to offer proof that you had run a previous marathon in a qualifying time, what today is known as a BQ (Boston qualifier). Following Amateur Athletic Union rules then in place, you would submit to a physical exam to ensure that you would not die of a heart attack and embarrass the organizers, but qualify for the race? No need. In the early years, us marathoners were few and far between. Until 1970, the largest field at the Boston Athletic Association Marathon (its official name) had been 285 runners in 1928.

Then in the 1960s, a seismic shift occurred. Running suddenly became popular as health-conscious baby boomers edged into middle age. For at least some, the Boston Marathon became a goal akin to the ascent of Mount Everest. In 1960, according to Tom Derderian’s history, Boston Marathon, only 156 started the race. A decade later in 1970, that number skyrocketed to 1,011, with 678 finishing under 4 hours.

I accept some of the blame (or credit) for the increase. In 1963, I wrote an article for Sports Illustrated titled “On the Run from Dogs and People,” focused on the Boston Marathon. Entries jumped from 285 that year to a record 369 the following year, and it seemed like several dozen individuals introduced themselves to me in the Hopkinton Gym saying they had started running (with Boston their goal) after reading my article. In truth, the bestselling book Aerobics by Kenneth L. Cooper, MD, and the gold medal won by American Frank Shorter at the 1972 Olympic Games did more to ignite the running boom, but long-distance running with Boston as its kingpin suddenly had become a mainstream activity.

The Boston Marathon at that time was organized part time by two individuals. Will Cloney was a sportswriter. Jock Semple was a trainer for the Boston Bruins and the Boston Celtics. They greeted the burgeoning number of marathoners with panic, fearing that the narrow roads between suburban Hopkinton and downtown Boston could not support more than 1,000 runners. So they imposed a qualifying time of 4 hours to limit the field to less than 1,000 runners.

Boston’s qualifying requirement merely spurred runners to train harder. Boston became the standard for marathon excellence. By qualifying for the Boston Marathon, runners achieved status among their peers. It earned you bragging rights to be able to say nonchalantly that you had “qualified for Boston.” Boston’s numbers continued to increase because once a runner qualified, it seemed almost obligatory to go to Boston to run. So the organizers lowered the standard from 4:00 to 3:30 to 3:00, until by the mid-1980s, if you were a male under 40, you had to run 2:50 to qualify.

That 2:50 standard was too tough. Four hours is a reasonable time for a runner of average ability who is willing to train hard, but to run the course more than an hour faster requires a certain natural ability. To get into the Boston Marathon, you needed to combine talent and training. Eventually, Boston relaxed its standards to 3:10 for the fastest age group (18 to 34), with a sliding scale of slower times in other categories, depending on age and sex. After the 2011 race filled in only 8 hours 3 minutes, the BAA toughened its standards and changed its registration procedures.

Currently, Boston limits its field to approximately 30,000 entrants, with 80 percent of them “qualified” runners and the rest runners who secure their starting-line positions by raising money for various charities. In 2019, charity runners raised $38.7 million. For the 2020 Boston Marathon, the qualifying standards for different age groups began at 3:00 for men ages 18 to 34 and 3:30 for women ages 18 to 34. The BQ standards often change from year to year. Current standards can be found on the BAA website: www.baa.org. How do you secure a BQ? What training program guarantees you a spot on the starting line? Let me be honest with you. Training programs, mine and those offered by other coaches, do not carry a guarantee. Each runner succeeds or fails by how well he or she trains and, yes, a certain level of talent is required. Nevertheless, you can improve your BQ chances if you do the following:

1. Think far, far ahead. Most of my marathon training programs last 18 weeks, but that may not be enough time. Unless you have enormous talent (and some folk do), you may need a year or two or more to gradually become a better (and smarter) runner, allowing you to secure a BQ. In my book Hal Higdon’s How to Train, I featured a program designed by Olympian Benji Durden that lasted 84 weeks and featured two half marathons and two marathons. In terms of time, Benji got it right. Exercise patience, and it may take a failure or two before you experience success.

2. Pick your qualifying marathon carefully. Most marathons provide life-changing experiences, but not all are equal when it comes to providing a qualifying opportunity. Hills or heat or both may rise to confound you, so look for races where the course is flat (or even downhill) and the weather is lovely more often than not. (See the accompanying sidebar for the marathons that produce the most Boston qualifiers.)

3. Get serious, and I mean really serious. You love running 5Ks and 10Ks, and there’s that fun half marathon that you do every year. Okay, racing is fun, but too much racing can drain psychic as much as physical energy. If you want that BQ, Boston must become a singular goal, not one of many goals.

4. Pickup basketball games are not cross-training. Neither is soccer. Neither is volleyball. And although cycling and swimming do qualify as cross-training, too much of those activities will not make you a better runner. If you get injured participating in other sports (cross-training or not), kiss that BQ attempt goodbye.

5. Some nonrunning activities are permitted. If achieving that BQ totally dominates your life, maybe you need to relax. Planning a family vacation? Reread tip #1: Think far, far ahead. If you have planned well, you can modify your training schedule to allow necessary downtime. All my marathon training programs have step-back weeks. And if you’re on a cruise, the biggest ships feature running tracks on the top deck.

6. Watch what you eat. Run past that cruise ship buffet. A lot of runners assume that as long as they run a lot of miles, they can eat whatever they want. Prime rib? Sounds great. Burgers right off the grill? What could be better? But maybe it is time to rethink your nutritional habits. Definitely avoid any weight-loss diets that might push you into a caloric deficit. Going on a crash diet to shed a few pounds should never be part of any BQ strategy.

7. The last few days are critical. Think of your comfort. Travel is not cheap—neither are airfares nor hotel rooms—but you invested a great deal of time and effort in your training. Raid the penny jar so you can afford to arrive in town a day early. A massage that final week might provide just the edge of prerace relaxation you need.

8. Don’t overlook your hometown. Considering all of the above, your hometown marathon may not be as “fast” as the ten listed here, but sleeping in your own bed may be worth an extra minute or two off your time. Being in a race where family and friends not only can cheer you but also can hand you something to drink or eat has got to be worth a few more seconds off the clock, and those few seconds may get you your Boston qualifier.

IT’S TIME TO RUN BOSTON

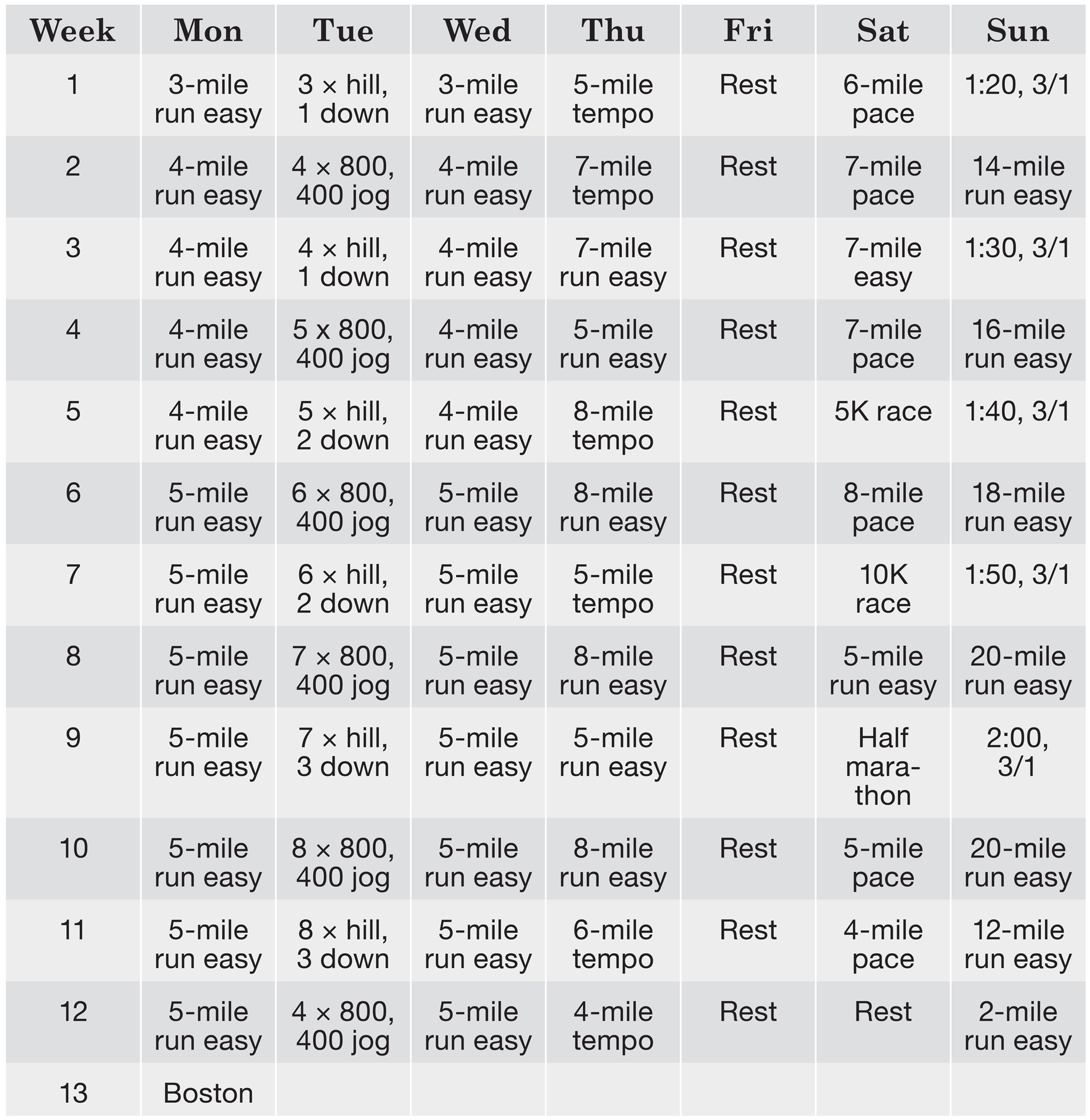

Now that you’ve qualified, how do you train for what is almost guaranteed to be a momentous experience? Welcome to Boston Bound. This 13-week program is aimed at those already qualified for Boston, not for those hoping to achieve a BQ. It starts in January, soon after the holidays, 13 weeks out. Long runs alternate between minutes and miles. Be aware that a 3/1 long run is easy the first three-quarters of the distance, then harder the final one-quarter. Hill training is necessary if you want to hit Heartbreak Hill in cruise control. Also, some of your hill training should include downhill repeats. This is not an easy program, but getting a BQ is not easy. If you are well-trained enough to include a BQ on your curriculum vitae it should not scare you.

A couple of warnings: It is not so much that the Boston Marathon has a difficult course (Heartbreak Hill is not that high), but it is a different course. Very few runners score PRs in their first Boston attempts. It took me five attempts to learn how to run Boston, but now I get to pass on what I learned to you. Get it right, training for Boston and racing at Boston, and you can join the best long-distance runners in the world.

Boston Bound