WE’VE LEARNED SOME painful lessons about the challenges that confront strategists in the face of unattractive industry forces. With this chapter, I begin mapping the path out of the wilderness: specifically, explaining how some astute strategists have managed to distinguish their businesses even in the face of such headwinds.

The journey starts with an individual: Ingvar Kamprad, the founder of IKEA who by all accounts built one of the world’s greatest fortunes. Like Richard Manoogian of Masco, Kamprad was in the furniture business, but his story couldn’t be more different. In 2010, his privately held company, which he started in 1943 at the age of seventeen, had sales of 23.1 billion euro, net profits of 2.5 billion euro, and gross margins of 46 percent.

And the numbers don’t even begin to capture IKEA’s powerful hold on consumers. As BusinessWeek put it, “Perhaps more than any other company in the world, IKEA has become a curator of people’s lifestyles, if not their lives. IKEA World [is] a state of mind that revolves around contemporary design, low prices, wacky promotions, and an enthusiasm that few institutions in or out of business can muster.”1

How did Kamprad succeed where Manoogian failed? He built his company by creating what I like to call a difference that matters. (The full meaning of this phrase will become clear as the story unfolds.) He did so, not by ignoring industry forces, as Manoogian did, but by creating a company that could thrive and add value in the midst of them.

If you’re one of the millions who have shopped at IKEA, you’ll likely have indelible memories of vast, bright, modern stores designed so that entering customers follow a winding path through a huge building filled with furnishings and a great miscellany of housewares. When you chose a piece of furniture—a simple Micke desk for 69 euro, or a ten-person Norden dining table for 269 euro—you noted the information on an order slip, continued on the path to a warehouse-like room, wrestled a flat box containing the item onto your shopping trolley, carted it home on the rooftop of your car, and assembled it yourself. If you brought the kids, you may have parked them in the on-site child care center; you may also have stopped at the restaurant to sample tasty and inexpensive food ranging from salmon to Swedish meatballs and lingonberry tarts. It’s almost a theme park: probably not a customer experience you’d relish if you’ve made your fortune, but when you were starting out, there was nothing that could match it.

RURAL ROOTS

One could say that Ingvar Kamprad was a natural-born entrepreneur. “Trading was in my blood” he told his biographer, Bertil Torekull.2 Kamprad was about five when his aunt helped him buy a hundred boxes of matches from a store in Stockholm that he then sold individually at a profit in his rural hometown of Agunnaryd, deep in the farmland of Smaland. Soon he was selling all sorts of merchandise: Christmas cards, wall hangings, lingonberries (he picked them himself), fish (which he caught), and more. At eleven, he made enough money to buy a bicycle and typewriter. “From that time on,” he recounted, “selling things became something of an obsession.”3

Before going to the School of Commerce in Gothenburg, Kamprad signed the paperwork to start his own trading firm, IKEA Agunnaryd [I for Ingvar, K for Kamprad, E for the family farm Elmtaryd, and A for Agunnaryd]. The mail-order business grew to include everything from fountain pens and picture frames to watches and jewelry. With a keen eye for value, Kamprad ferreted out the lowest-cost sources. Frugality was the norm in Smaland. Its farmers, eking their living from a harsh and spare environment, had to make every penny count.

Noticing that his toughest competitor in the catalog business sold furniture, Kamprad decided to add some to his offerings, supplied by small local furniture makers. Furniture quickly became the biggest part of his business; in the postwar boom, Swedes were buying a lot of it. In 1951, at age twenty-five, he dropped all his other products to focus exclusively on furniture.

Almost immediately he found himself in a crisis. Growing competition from other mail-order firms led to a price war. Across the industry, quality dropped as merchants and manufacturers cut costs. Complaints started to mount. “The mail order trade was risking an increasingly bad reputation,” Kamprad said.4 He didn’t want to join the race to the bottom, but how could he persuade customers that his goods were sound when they had only catalog descriptions to rely on? His answer: create a showroom where customers could see the merchandise firsthand. In 1953 he opened one in an old two-story building. The furniture was on the ground floor; upstairs were free coffee and buns. Over a thousand people came to the village for the opening, and a gratifying number wrote out orders. By 1955, IKEA was sending out a half a million catalogs and had sales of 6 million krona.

Kamprad understood his customers on a personal level. As he would later say, in explaining IKEA’s philosophy, “Since IKEA turns to the many people who as a rule have small resources, the company must be not just cheap, nor just cheaper—but very much cheaper . . . the goods must be such that ordinary people can easily and quickly identify the lowness of the price.”5

By following this philosophy, Kamprad became a force to contend with in the Swedish furniture industry—and, not liking his low prices, the industry struck back. Sweden’s National Association of Furniture Dealers began pressuring suppliers to boycott him and, with the support of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce, banned him from trade fairs. Many of the suppliers stopped selling to him, and those that continued to do business with IKEA resorted to cloak-and-dagger maneuvers: sending goods to fictitious addresses, delivering in unmarked vans, and changing the design of products sold to IKEA so they wouldn’t be recognized. Soon Kamprad was suffering the humiliation of not being able to deliver on orders.

He counterattacked on several fronts—for example, he began paying suppliers within ten days, as opposed to the standard industry practice of three or four months, and he started a flock of little companies to act as intermediaries. These moves helped, but IKEA was growing rapidly and supplies were short. Without a reliable source of supply, Kamprad feared his business would be doomed.

Having heard that Poland’s communist government was hungry for economic development, Kamprad began scouring the Polish countryside. He found many eager and willing small manufacturers laboring in the shadow of the bureaucracy. Their plants were antiquated and the quality of their products was dreadful, so Kamprad located better-quality (though used) machinery in Sweden. He and his staff moved the machinery to Poland and installed it, working hand in hand with the manufacturers to raise productivity and quality. The furniture they turned out ended up costing about half as much as Swedish-made equivalents and Kamprad was able to nail down his costs on a huge new scale.

Thus the boycott turned out to be what I call an “inciting incident,” to borrow a phrase from screenwriter Robert McKee—an event that propelled a critical strategic shift.6 “New problems created a dizzying chance,” Kamprad said. “When we were not allowed to buy the same furniture others were, we were forced to design our own, and that came to provide us with a style of our own, a design of our own. And from the necessity to secure our own deliveries, a chance arose that in its turn opened up a whole new world to us.”7

To Kamprad, it wasn’t enough to simply source in developing countries. He also brought extraordinary determination and imagination to his drive for lower costs. For example, he wasn’t afraid to draw on unconventional sources. He turned the job of making a particular table over to a ski manufacturer, who could deliver it at an especially low price. He bought headboards from a door factory, and wire-framed sofas and tables from a maker of shopping carts. IKEA was also a pioneer in building “board-on-frame furniture,” comprised of finished wood on a particleboard core, which is both cheaper and lighter than solid wood.

Then, of course, there is the iconic IKEA packaging—the famous flat pack with its do-it-yourself assembly. While the company didn’t invent this approach, it was the first to grasp and systematically exploit its full potential. The flat pack provides huge cost savings by making shipping, distribution, and storage much more efficient and thus much cheaper. It saves manufacturing steps; it saves shipping costs from factory to store; it saves stocking and handling costs in the store; and it eliminates delivery costs for most customers.

IKEA opened its first store in 1958 in Almhult. Five years later it opened one in Norway, and two years after that, a second Swedish store in Stockholm. It became a nascent global player with openings in Switzerland in 1973 and Germany in 1974. It entered the United States in 1985, China in 1998, Russia in 2000, and Japan in 2006. In 2010, IKEA had 280 stores in twenty-six countries, and served 626 million visitors.8

BEYOND LOW PRICES

So how do you account for IKEA’s success in this terrible industry?

Most likely your immediate thought is “low prices, low prices, low prices.” Indeed, IKEA’s prices are so low they’re not just a difference in degree from competitors’ but a difference in kind.

Over the past decade, the company has lowered its prices by 2 to 3 percent a year on average. Every aspect of IKEA’s operation is subject to ongoing scrutiny to see where further costs can be taken out. Even flat packs have been repeatedly redesigned to gain small efficiencies in the use of space. Kamprad regarded the customary perks of business leadership as waste, too. Stories are legend of his flying coach class or taking a bus instead of a taxi or limousine. It’s an attitude that’s been adopted wholeheartedly by others in the company who speak of spending money unnecessarily as a “disease, a virus that eats away at otherwise healthy companies.”9

But IKEA is not a dollar store: Low prices don’t begin to tell the whole story. Scandinavian design was becoming popular around the world in the 1950s and it suited IKEA’s strategy perfectly. The simplicity of the clean lines made the furnishings particularly appealing; it also made them cheaper to produce than more ornate designs. Kamprad pushed this envelope farther, hiring first-class talent who could design for both style and for frugal manufacturing techniques. Perhaps IKEA’s greatest design achievement has been to make its furniture look and feel more expensive than it is. A turning point came in 1964 when a respected Swedish furniture magazine compared IKEA furniture with more highly regarded brands. IKEA’s, it found, was often as good or better. That shocked the industry and helped to persuade consumers that they had nothing to lose—either financially or in terms of status—by shopping at IKEA.

Unlike so many discount retail stores, IKEA’s are anything but dark and dingy. The company’s vibrant colors (mostly blue and yellow, the colors of the Swedish flag) are everywhere, and except for the weekend crowds, the stores are pleasant places to visit. You can make a day of it: Come with the family, try out the sofas, use the computerized tools to design your own kitchen, and have a full-fledged Swedish meal at the restaurant. If, at the end of the day, you’ve bought too much to load onto your car, you can rent an IKEA van to drive it all home, or even pay to have things delivered, assembled, and set up.

So, what is it that is special about IKEA? I ask you. Low price? Design? Flat pack? Swedish meatballs? What? The answer, of course, is “all of the above.” The centerpiece is low cost—without that, nothing else works—but everything else not only supports low cost but adds its own distinctive attraction.

At this point, you, like many managers, may feel like, “Okay, we’re done—we’ve cracked the case. We know the answer, time to move on.” Maybe so. But what is the real lesson here? What do you take with you to apply to your company? That low cost with some added distinctive features is a winning combination?

Often it is.

But what if I tell you there is a deeper insight here, an insight that applies to all businesses whether you’ve decided to compete on low price or with differentiated, specialty products. It’s something else that was behind everything IKEA did.

A CONCEPT COMPANY

If Ingvard Kamprad were here and we asked him to describe the essence of what IKEA was doing, what would he say?

His own words are instructive: “We are a concept company.” He goes on to describe the idea that guides the firm. IKEA offers “a wide range of well-designed, functional home furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible will be able to afford them.” This serves the company’s aim to create “a better everyday life for the many.”10

These words weren’t said by Kamprad on rare occasions. He said them often, over and over. He wrote them out, and more like them, in statements and booklets he printed and distributed to employees. All new employees are indoctrinated with these ideas, and they’re prominent in the company’s annual report today.

Although IKEA calls this statement its “concept,” the word I prefer is purpose. Purpose is the way IKEA or any other company describes itself in the most fundamental terms possible—why it exists, the unique value it brings to the world, what sets it apart, and why and to whom it matters. Notice how IKEA’s purpose as expressed above answers all these questions.

I suspect, though, that some of you, like some EOPers, are leery of lofty prose. Perhaps you consider Kamprad’s words mostly PR fluff—fancy words to dress up a hard-nosed, cost-cutting approach. But these words don’t just “dress up” low prices. On the contrary, they are what drive IKEA’s low prices and all the other features that make it stand out.

To underline the point, consider something else Kamprad wrote in “A Furniture Dealer’s Testament,” a document he prepared to keep the growing company focused on what it was all about:

We have decided once and for all to side with the many. . . . The many usually have limited financial resources. It is the many whom we aim to serve. The first rule is to maintain an extremely low level of prices. But they must be low prices with a meaning. We must not compromise either functionality or technical quality.11

So it wasn’t low prices alone that drove IKEA. Low prices weren’t the goal but rather a means to an end: “low prices with a meaning”—a better everyday life for the many.

What was Masco’s purpose in furniture? It didn’t really have one, did it—other than a vague belief that it would have some sort of scale advantage and would bring professional management skills and capabilities to an industry that sorely lacked them. In contrast, IKEA’s clear and compelling purpose addressed a long-lived market need, created a distinctive niche, and mattered a lot to its customers.

As you mull the idea of corporate purpose, you may make the connection to the more familiar “competitive advantage.” In fact, the terms purpose and competitive advantage could be used in conjunction with each other, but competitive advantage places the focus on a firm’s competition. That’s important, but it’s not enough. Leaders too often think the heart of strategy is beating the competition. Not so. Strategy is about serving an unmet need, doing something unique or uniquely well for some set of stakeholders. Beating the competition is critical, to be sure, but it’s the result of finding and filling that need, not the goal.

Consider the power of purpose and the differences it spawns across firms. In the last chapter we looked at the average profitability of different industries as a whole. We treated each industry as if it were a single entity, and showed the average profitability of firms in each industry, the industry effect. Here we consider the variation in profitability within an industry, across players. This is the firm effect—the difference between an individual firm’s profitability and the average profitability in its industry. Positive or negative, large or small, it’s the sum of the impact of all a firm’s actions.

Firm effects are directly tied to the work of a strategist, and over the long run are one of the best indicators of success or failure on the job. Within an industry, they can vary widely, even though most of the players work in a similar context and face largely the same competitive forces (See Exhibit 4-1, below). In tobacco, for example, Imperial Tobacco and Altria have returns that are even higher than the industry average, giving them positive firm effects. Reynolds American and others, in contrast, have negative firm effects. In airlines, Ryanair and Southwest buck the negative industry return while many of their competitors fare far, far worse.

The chart on Furniture Retailing shows the net profit margin for a number of furniture retailers around the globe. Average profits in the industry are low (4.9 percent), but some firms do better than the average, and IKEA (whole returns are estimates) is at or near the top of the pack.12

The key question: What explains the firm effect that creates such differences among players in an industry? What can lead a company like IKEA to excel even in a business as tough as this?

The answer, I believe, begins with purpose. Purpose is where performance differences start. Nothing else is more important to the survival and success of a firm than why it exists, and what otherwise unmet needs it intends to fill. It is the first and most important question a strategist must answer. Every concept of strategy that has entered the conversation of business managers—sustainable competitive advantage, positioning, differentiation, added value, even the firm effect—flows from purpose.

EFFECTIVE PURPOSES

All this sounds attractive to the leaders I’ve worked with. It seems to lift their work above the dog-eat-dog world of cutthroat competition and harsh reality. Most of them want to feel that what they do matters in some context larger than themselves and larger even than their companies. They want to play their roles on as large a stage as possible. And so they embrace the idea of purpose because it feels inspiring. And, as we’ll see, that’s part of it. But to be a serious guide for a company, a purpose needs to do much more.

A good purpose is ennobling. It makes a firm’s endeavors noble or more dignified. In addition to its other merits, a good purpose can satisfy this need. It is inspiring to all involved, to the employees pursuing it, to customers, and to others in your value chain. The people at IKEA don’t believe they’re flogging cheap furniture. They believe they’re creating “a better everyday life” for the many people who can’t afford top-end furnishings.

In a Gallup poll nearly all respondents said it is “very important” or “fairly important” to them to “believe life is meaningful or has a purpose,” but less than half of the workers in any industry felt strongly connected to their organization’s purpose. Equally interesting, a number of people in less than life-and-death careers (for example, septic tank pumping, retail trades, chemical manufacturing) felt a strong connection to the goals of their organizations, while others in some traditional “helping” fields (for example, hospital workers) felt far less connection. An analysis of the work concluded:

There is no such thing as an inherently meaningless job. There are conditions that make the seemingly most important roles trivial and conditions that make ostensibly awful work rewarding. . . . The least engaged group sees their work as simply a job: a necessary inconvenience and a way of earning money with which they can accomplish personal goals and enjoy themselves outside of work.13

Don’t overlook the role of purpose in fostering the care and commitment that lead people to produce good results. Consider a business forms company that sells its services to small businesses. You can’t get much more mundane than invoices and sales slips, but the people there said: “What we do isn’t glamorous, but it’s essential. When you can’t pay people or give the customer a receipt, the business stops running.”

A good purpose puts a stake in the ground. It says “We do X, not Y.” “We will be this, not that.” It’s a commitment.

Choosing to be one thing means not being something else. Michael Porter recognized that such choices involve trade-offs—letting some things go in order to be better at something else.14 Companies that don’t choose, for whatever reason, run the risk of ending up in no-man’s-land, being nothing of distinction to anyone. If your purpose does not preclude you from undertaking certain kinds of work, then it’s not a good purpose. Purpose, like strategy, is about choice, and a real choice contains, if only implicitly, both positive (“We do this”) and negative (“By implication, then, we don’t do something else”) elements.

One executive I worked with in the EOP program, Pedro Guimaraes, a CEO of a small but growing movie production company, discovered this only after he clarified his purpose. His firm was primarily backed by an angel investor, a woman who had become very wealthy from her own business ventures and now, through this company, was pursuing a longtime personal love of movies and culture in general. As part of our work in the program, Pedro wrote out his purpose for the company, describing how it would make money through the production of advertising and movies that were commercial successes.

When he showed the purpose to his investor, he discovered what had only been simmering under the surface of their relationship. He wanted to produce top-grossing box-office hits and make profits. She had little interest in those and instead, primarily wanted to produce art films, the kind once made by Ingmar Bergman in Sweden or Federico Fellini in Italy. At that moment he finally understood why the investor had balked at a number of projects he had proposed. From the outset they had been on different pages, but had never dug deeply enough into their respective purposes to see the incompatibility. They parted company amicably, and each went on to ventures that were more consistent with their different aims.

A good purpose sets you apart; it makes you distinct. If you can only describe your business generically—“We’re a PR firm” or “We’re an IT consulting company”—then you don’t have a real purpose. Somehow the reason you exist, the specific customers you’ve chosen to serve, the market needs you fill, must set you apart from others who generically do what you do. Generically, IKEA is a furniture retailer, but that description doesn’t begin to say why it matters or what distinguishes it from others in the industry. Here is how IKEA describes its difference:

From the beginning, IKEA has taken a different path. . . . It’s not difficult to manufacture expensive fine furniture. Just spend the money and let the customers pay. To manufacture beautiful, durable furniture at low prices is not so easy. It requires a different approach. Finding simple solutions, scrimping and saving in every direction. Except on ideas.15

Where do differences come from? They arise from innovation, new ideas, and deep insights about how things are and how they could be better in some consequential way. These can be anything from a new production technology that enhances efficiency, to new, different, and more appealing products, to a change in the way products or services are sold or delivered. Sometimes what matters is not just one innovation, but a cluster of innovations that flow from a new concept, a new way of doing business. This was the case for IKEA. Its greatest innovations were not in original furniture designs, or even in the technical invention of the flat pack, but in a new idea of how to go to market and how to provide a set of customers with products and a shopping experience that met their needs resoundingly well.

IKEA’s experience illustrates a key advantage of a good purpose. A clear sense of what a company is striving to do can serve as a focal point or a core organizing principle around which a whole set of innovations and distinctive features can coalesce.

Above all, a good purpose sets the stage for value creation and capture.

Good economics are not the only reason your business exists, but without them, it’s unlikely that any of your other goals will be realized.

Whatever your purpose, it must mean something to others in ways that produce good economic outcomes for you. What made IKEA’s purpose so powerful was not just that it was distinctive or well-defined, or that it made people feel part of something bigger and more important. It also drove IKEA’s superior performance in its industry.

ADDING VALUE FOR EVERYONE

The acid test, then, of a purpose is this: Will it give you a difference that matters in your industry?

Not all differences are equal. You need a difference with real consequences. I often see companies claim differences that in fact are simply points of distinction without much consequence in their industries—“one-stop shopping,” “oldest continually operated,” “largest independent supplier.” Even a legitimate difference such as “best-in-class quality” is often rendered meaningless by companies that trumpet the words but don’t make the investments or tough trade-offs such a goal requires.

IKEA’s purpose set it up to deal with the industry forces that scuttled Masco and many others in the furniture business. The company took two of the industry’s biggest problems—price competition and customers’ low willingness to pay—and made them a virtue through specific techniques such as lean manufacturing, the flat pack, and store design. It dealt with the industry’s costly practice of manufacturing a huge variety of furnishings by selling a limited selection of furniture pieces within one style.

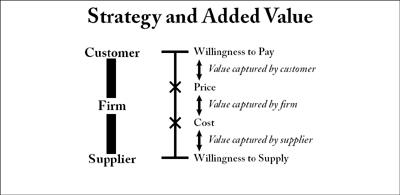

Many people think about strategy as a zero-sum game between a firm and its competitors, suppliers, and customers: How do we win? How do we get what’s best for us? In doing so, they largely focus on the sphere that’s closest to home: increasing their own profits—through higher prices or lower costs. On the Added Value chart, it’s the region called “Value captured by firm.”16

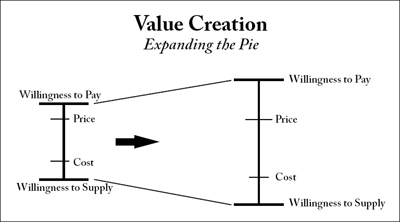

A trio of economists17 —Adam Brandenburger, Barry Nalebuff, and Harborne Stuart—who study game theory suggest a wider angle. They remind us that managers need to think not only about what’s best for their own firms, but also about how what they do affects others. This involves the two outer lines: Customers’ Willingness to Pay (essentially customers’ satisfaction with a good or service) and Suppliers’ Willingness to Supply (essentially their opportunity cost—the lowest price at which they would be willing to sell to a particular firm). It’s when a company drives a wider wedge between these lines—expanding the total value created—that its existence matters in an industry. When it does so, it is much more likely to be able to claim some of the value for itself—i.e., increase its own profitability—without making its partners in trade less well off.

Wal-Mart is a classic example. It offers its customers good quality products at considerably lower prices, increasing the value customers capture from the relationship. At the same time, Wal-Mart lowers its own costs by lowering the costs of its suppliers. It does this by buying in scale, sharing information, and taking costs out of their systems.

There are interesting parallels between Sam Walton and Ingvar Kamprad—for example, they both nurtured their vision of low-cost retailing in backwaters, where they learned how to court customers without much money. The most important parallel, though, from the standpoint of strategy, is that they both understood the benefits of adding value through one’s existence, not just fighting over who gets the biggest share of the pie.

As it was growing into the company it has become, IKEA helped its suppliers save money. It designed furniture to be less expensive to manufacture. Its flat-pack approach eliminated significant shipping and assembly costs. It ordered in volume and provided data that made its suppliers more efficient. For suppliers, all of these drove down the costs of doing business with IKEA, and, in turn, reduced the price at which they were willing to sell to the firm.

There’s still more to IKEA’s difference that matters. Through design and the distinctiveness of its approach, it created name recognition in a business not known for strong brands. It broke an ancient tradition of furniture as a long-term investment, and promoted the view of furniture as fashion. And it countered customers’ general reluctance to shop for furniture by providing free child care and low-priced restaurants with good food, both of which increased the length of time people spent in the store.18 So IKEA created value all around: Vendors could produce and sell for less, customers were pleased with the experience yet able to pay less, and IKEA was able to capture some of that value itself.

Successful premium-priced players, like BMW or Disney, create value differently. Their goal is to provide uncommonly good products or services that command high prices and generate particularly high levels of customer satisfaction. To do so, they typically incur higher-than-average costs that are more than compensated for by increases in customers’ willingness to pay.

For any firm, however, the logic is the same: You create value by driving the widest wedge you can between the satisfaction of your customers and the all-in costs of your suppliers.19 That means not only moving your own costs or prices relative to others in the industry, but moving one or both of those outer lines as well.

Viable purposes, worthy of guiding everything else that happens in a company, must matter not only to you but also to those with whom you do business. Creating value for others is the surest way to capture some yourself.

DOES YOUR BUSINESS MATTER?

It’s not as easy as you might think to know whether your business has a viable purpose, or whether it truly adds value in your industry. Financial success at any given moment is an indication, but may prove fleeting. However, there is one simple question20 that—if you can answer it honestly—will give you a good idea. In essence, it’s the one I asked you at the start of this book:

If your company disappeared today, would the world be different tomorrow? Despite our long discussions about purpose, and their general buy-in to the idea, this question always catches EOP executives by surprise. Frankly, it’s not a question most have been asked or asked themselves. It’s a real soul-searcher. But it’s one I hope you recognize that you need to answer.

Here’s what it means to be different in a way that matters in your industry. It means that, if you disappear, there will be a hole in the world, a tear in the universe of those you serve, your customers. It means customers or suppliers won’t be able to go out and immediately find someone else to take your place.

If you don’t have that difference, nobody will mourn you when you’re gone.

And if they won’t miss you then, how much do they need you now?

One more question: Whose job is it to find an answer, to make sure there’s an answer?

It’s your job, the job of the strategist, the leader who’s responsible for the success and survival of the firm.

It may not be the job of the strategist to invent a firm’s purpose on the lonely mountaintop and then come down and deliver it. Many people may be involved in its creation. But whether there is a purpose and whether that purpose is viable is a leader’s first responsibility.

This is the strategist’s job.

Are you a strategist?