IT’S YOUR TURN.

You’ve studied the successes and setbacks of Masco, IKEA, and Gucci. You know that every business, every organization, needs a strategy. You understand the importance of a meaningful purpose and a tightly aligned system of value creation. Now it’s time to look at your own company. What’s your strategy?

When I put this question to the entrepreneurs and presidents toward the end of our program, many of them nod confidently. By this point we have been talking about strategy for a long time and they have a good grasp of the principles. And they’ve repeatedly shown their ability to identify the strengths and weaknesses in the strategies of well-known and celebrated firms—at a safe distance.

But when I press them to describe their own strategies, many struggle. Beyond somewhat sweeping statements, they often have trouble articulating what their businesses actually do or what sets them apart. The ideas come out vague; the statements they write down tend to be generic and uninspired.

It’s a struggle because analyzing yourself is always harder than analyzing someone else. The cool objectivity and clarity you enjoy as a spectator often gives way to uncertainty and doubt when you start to confront the reality of your own situation.

While the intense class work exposes EOPers to the tools of strategy, for many there is a chasm between their understanding of how strategy works and truly being strategists—like the difference between war games and war, between reading about how to swim and actually swimming.

The reality is that it can be hard to put strategic thinking to work in one’s own business. Managers often start off on the wrong foot, failing to think carefully about purpose, or they don’t take the process far enough to see how all the activities in their businesses support (or don’t support) their intended direction. Studying other companies’ dilemmas and other managers’ triumphs is a good start, but it’s not enough. To develop into a successful strategist you must live the experience. You must wrestle with the specific purpose of your company, find the differences that matter, define your system of value creation, and pull it all together into a compelling strategy.

There’s only one way to begin effectively: write all these things down.

Writing imposes a discipline that no amount of talking can match: It gives structure to your thinking. It forces you to define in carefully considered words what your business exists to do and how each part of it contributes to the effort. Once that’s laid out, you can analyze why the whole thing works or doesn’t and what could make it stronger.

This is not a casual exercise: You will find yourself visiting and revisiting your work. A winning strategy doesn’t just rise up out of your keyboard in an afternoon or emerge from a weekend retreat with your team. Rather, for most leaders, it comes into focus over time, as you analyze and reflect on your business and work through each step of the process.1

In addition to building your strategic skills, the experience helps you to clarify your strategy for all of your stakeholders. Many companies never accomplish this, instead offering up grand statements or euphemisms that convey very little about the business itself or its particular reason for being. As we discussed this in class one day, one of the EOPers told the group that before coming to campus he had looked up the websites for all 170-plus companies that would be represented in the program. What he found often wasn’t impressive. Very few, he reported, gave him a credible sense of what the company was really about—what made it special, or why he should care about it.

Other hands went up; those people had done the same thing and come to the same conclusion. There were a lot of sober faces around the room as the message sank in.

The internal costs of unclear strategies are, arguably, even greater. As information technology consultant James Champy notes, “few companies are explicit about the future: in what markets they will operate, how large and quickly can they grow, how will they differentiate. . . .” This vagueness, he said, leaves employees feeling completely in the dark, unable to accurately anticipate the firm’s future needs or do their jobs well. Instead, they must resort to reading the tea leaves, trying to guess the strategy by analyzing management’s actions.2

A clearly defined strategy steers the company, providing a compass for where you want to go. It makes you a better communicator, giving you the words to articulate what you are doing and why. Your customers and investors will understand you better. Your employees won’t have to guess what you’re up to and they will know how their work fits into the whole and what will be expected of them.

In the EOP program, this strategy development process has led to dramatic insights: Some executives come to the painful conclusion that they need to jettison a product line or sell a whole business; others uncover missed opportunities or stake out new positions. Three cases in brief:

Dr. Richard Ajayi, the head of The Bridge Clinic, Nigeria’s first focused in-vitro fertilization clinic, took enormous pride in its high quality standards and differentiated service. But, looking closely at his experience, he realized that customers who could afford the company’s prices often went overseas for care, while those in the low to middle end of the market didn’t understand the value of the science involved and couldn’t pay the premium price. In response, Ajayi reduced all costs unrelated to patient outcomes, explicitly benchmarked the clinic’s outcomes on the highest international standards, and recast it as high quality but affordable health care with the motto: “We are within your reach, make the decision and grasp.” The repositioning enabled the clinic to meet the needs of thousands of patients and generated unprecedented growth.

Geoff Piceu’s grandfather founded United Paint and Chemical in 1953, and the company grew into a solid player in the automotive coatings industry. But in the early 2000s, competition in the industry was cutthroat. The younger Piceu, who had taken over by then, described the competitive landscape as “a disaster you wouldn’t want to hear about,” and Michigan-based United was struggling to make a profit. Piceu concluded that his best chance for survival was to become the low-cost producer. Having learned that innovation had a short shelf-life in automotive coatings —it gets commoditized quickly—he abandoned the expensive basic research that was traditional in the industry, choosing instead to adopt a “second-to-market” approach by acquiring innovation and being a fast follower. He also reshaped operations into a paragon of lean manufacturing. The new strategy roughly doubled United’s productivity relative to competitors and led to double-digit sales growth.

Eugene Marchese, the founder of an Australian architecture firm, was considering expansion to other residential segments and geographies in his home country. At the time, however, it was not yet clear what the firm’s unique advantage would be in those new markets. Instead, he decided to expand to 2nd Tier cities overseas where he could leverage the firm’s award-winning designs for urban-condominiums and share personnel and other resources across time zones. Today, Marchese Partners has offices in cities ranging from Sydney to San Francisco to Guangzhou, and provides its innovative design services and commercial sensitivity to leading developers anywhere in the world.

In all these cases, the work began by revisiting the organization’s purpose, a good place to start the examination of your own business.

STATE YOUR PURPOSE

As we discussed in chapter 4, your company’s purpose describes the unique value your firm brings to the world. It’s the throbbing heartbeat of your strategy—the grand pronouncement of who you are and why you matter. It should be specific and easy to grasp because the rest of your strategy flows from and supports this beginning.

Too often I see companies describe their purpose as something like, The best company in XYZ industry, specializing in satisfied customers, or Our nonprofit is committed to improving the quality of life in our community. Or this:

We will provide branded products and services of superior quality and value that improve the lives of the world’s consumers, now and for generations to come. As a result, consumers will reward us with leadership sales, profit and value creation, allowing our people, our shareholders, and the communities in which we live and work to prosper.3

How could you even guess that the last one is from Procter & Gamble, the giant consumer products company?

Contrast that with some other companies:

__________: To bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world.4

__________ is built upon finding ways to do online search better and faster in an increasing number of new places and in ever more efficient ways.5

And this:

The ______Group is the only manufacturer of automobiles and motorcycles worldwide that concentrates entirely on premium standards and outstanding quality for all its brands and across all relevant segments.6

Do you recognize Nike, Google, and BMW? They each have a grasp on why they exist and who they are.

What is your company’s purpose? Is it something everyone in your company knows?

Sometimes a slogan can begin to capture the purpose—or at least start the discussion—if it gets to the firm’s unique added value. EOPer H. Kerr Taylor, founder of a Houston real estate firm called AmREIT, told me where he got the initial idea for his company. As a young man visiting Florence, Italy, during a post-graduation tour of Europe, he was impressed by the big, beautiful, multipurpose buildings on a plaza that housed shops and offices on the ground floor, and apartments above. He asked an older gentleman sitting next to him at a café who the owners were. “These buildings are owned by some of the wealthiest families of Italy,” the man told him, explaining that they were rarely, if ever, sold. “That is how you pass wealth down from generation to generation.”

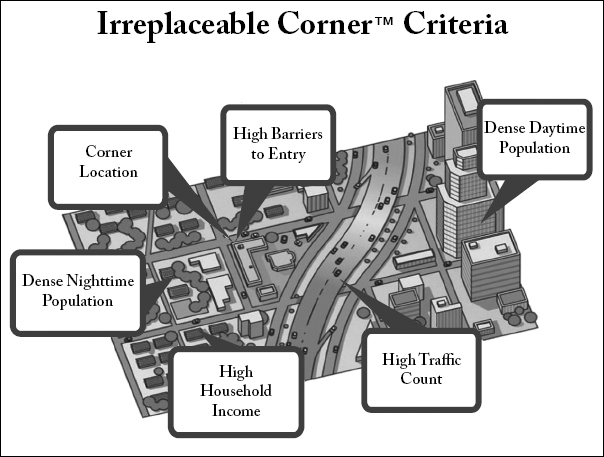

After earning an MBA and a law degree and returning home to Houston, Taylor set out to try to build a portfolio like the ones that supported those wealthy Italian families. Because his nascent company was short on capital, he initially focused on buying and leasing back great corner properties with one tenant, such as bank branches or restaurants. Eventually he moved up to entire shopping centers, all situated on prime corners. Along the way his company latched on to a slogan that described its work: the “Irreplaceable Corner” Company. It was a powerful moniker: “When people saw that on our sign, it stuck with them,” he said.

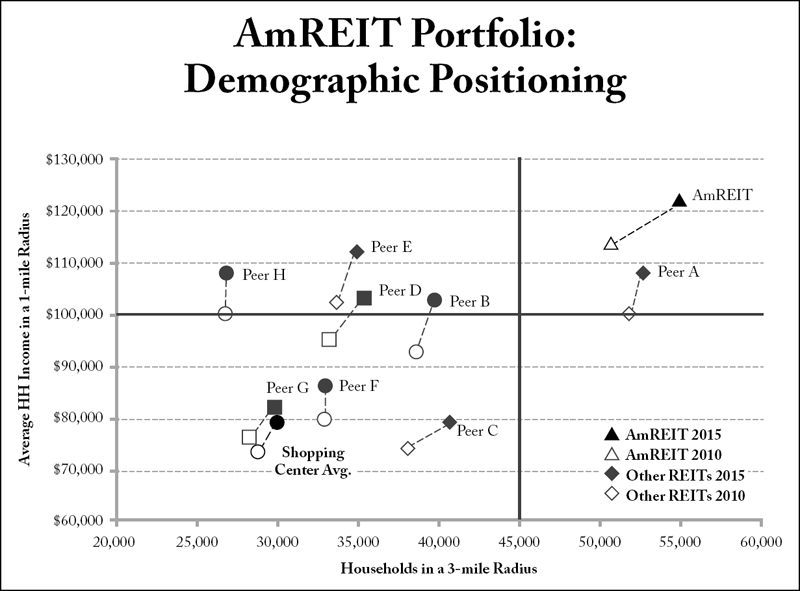

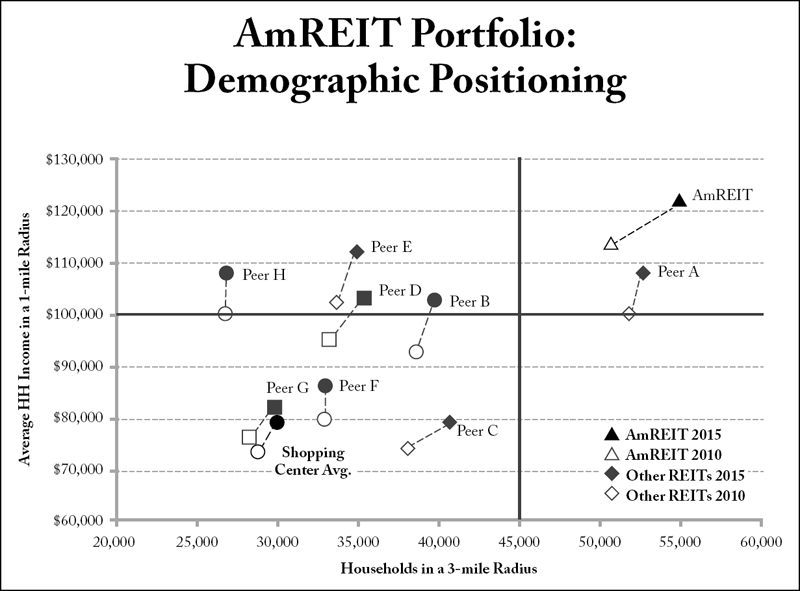

At the time Taylor joined EOP, his business had hit a plateau after more than two decades of growth. As he began to formulate a strategy statement, he and his executive team experimented with different ways to tell their story. This seemingly simple exercise led to major revelations about the nature of the business, and its difference that matters. When they put together a chart that mapped their properties and those of their top peers (over 800 properties in all), it was clear that AmREIT, though relatively small compared with industry giants, was a leader in focusing on real estate near high numbers of affluent households, a position that was particularly attractive to big-money investors. Using 2015 demographic projections, the gap between them and their peers grew even larger. Only one other major real estate company even came close.

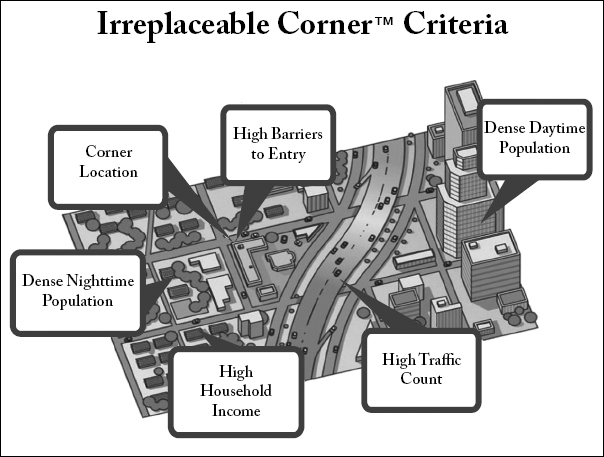

As Kerr and his team studied the chart and chewed on the language in their strategy, they began to ask what “The Irreplaceable Corner” really meant. Their efforts to nail down the firm’s purpose, and to ease its implementation, drove them much deeper into defining the kind of properties the company would buy, where they would be located, and how they would be chosen. This yielded highly specific criteria: the corners would be near large numbers of households, especially affluent ones; near high-traffic roads, and in areas with dense daytime and nighttime populations.

Crystallizing the company’s purpose led to a better understanding of what made its approach different and effective. It created a positive feedback loop. Not only did the new depth of detail help the company improve its operations, Taylor says, it also helped fit the firm’s strategy to its purpose, tell AmREIT’s story to employees and potential tenants, and win the attention of institutional investors who tend to overlook a company of AmREIT’s size.

To Taylor’s surprise, a good part of the initial process was about words. “I didn’t understand how important language was, trying to get the words correctly so you could communicate to others and, in the process, really communicate to yourself in a clear way,” he says.

AmREIT’s work fits the definition of corporate purpose that John Browne, former CEO of British Petroleum, spelled out in an interview with the Harvard Business Review: “Our purpose is who we are and what makes us distinctive. It’s what we as a company exist to achieve. . . .” As you work to identify and define the purpose for your own company, don’t stop with your first idea, but like Taylor, refine and clarify. The more precisely you can express it, the better the anchor it will become for developing your strategy—and, quite possibly, the more new insights you will gain into your business.

DEVELOP YOUR SYSTEM OF VALUE CREATION

By now you know that a company’s purpose is just a beginning. As discussed in chapter 5, it gives you the right to play, and puts you in the game. But it doesn’t mean you have the right to win. Just as De Sole made sure that each component of the Gucci enterprise—design, sourcing, stores, products, pricing, and so on—aligned with the company’s purpose, so must all of your activities and resources work in concert to support your own purpose.

You need to pinpoint who the customer is early in the process. But which customer? It’s not always the end user. Laura Young joined Leegin, the predecessor company of Brighton Collectibles, in 1991, when it was primarily a seller of men’s belts, and the owner, Jerry Kohl, wanted to expand into ladies’ leather goods. Since then, the company has added handbags, wallets, jewelry, and shoes, creating a significant niche as a boutique specializing in women’s moderately priced accessories. But even now, with over $350 million in annual sales, Brighton remains an unconventional company. Still owned fully by Kohl, there is no board of directors, no organization chart, and few formal titles. Kohl and Young work together as partners managing the company.

When Young began to define the strategy for Brighton, she struggled with where the company’s focus should be. The question of who the customer was loomed large: Was it the end consumer, the women who snapped up the matching pieces and shared their finds with their friends, in what Young calls “Girlfriend Marketing”? Was it the owners of the several thousand largely family-owned specialty boutiques that carried Brighton’s accessories or the sales associates in those boutiques and in Brighton’s company-owned stores? Or, was it the roughly one hundred dedicated sales representatives who called on all those stores?

Each group mattered, and each played a role in Brighton’s unique approach to the market. Ultimately, Young decided that the people who sell its products—the company’s sales representatives and the stores’ owners and sales associates—were its customers because they were the ones whose dedication could most influence the consumer’s purchase decision. Keeping them happy, and their work profitable, was key to Brighton’s own health.

So how does Young align Brighton’s operations—its system of value creation—behind these salespeople?

To keep merchandise fresh and interesting for them, the company makes “a little bit of a lot of things,” rather than huge quantities of a few items. That means the retailers can vary the choices and give the women who buy its products a lot of different options to choose from. Brighton also keeps the sales associates engaged with a steady flow of creative motivational events, seminars, and other opportunities to learn about the brand. For nearly two decades, Young and Kohl have taken hundreds of store operators and employees on trips to Los Angeles, Hong Kong, China, Taiwan, and Italy where they tour factories, eat meals together, and have continuous time for collaboration.

“We do things differently from other companies in our industry,” says Young. “We make sure we reach the sales associates who are the ones interacting everyday with customers. There is a real passion to what we do. A real spirit for the brand.” Fostering that spirit is crucial, she continues. “Without passion the sales associates can’t do what they need to do in their stores. They have to have a point of difference. The customer has to have a good experience because she has so many other options.” These days those options include the Internet. And—all retailers take note—Brighton’s motivated sales associates provide something you can’t get online. “The customer needs to feel good every time she goes into the store,” says Young. “She needs to have a great shopping experience, and a real personal and warm connection with the sales associate who is helping her.”

Importantly, Brighton also protects the boutiques by refusing to sell to big department stores such as Macy’s, Dillard’s, and Neiman Marcus. They have come courting, but Young has turned them all away, sometimes sending flowers or cookies with her sincere apologies that she won’t do business with them.

In return, Brighton makes an unusual demand of its retailers: It requires them to sell at a minimum resale price in order to protect the integrity of the brand so that customers know they are being treated fairly no matter where they shop for Brighton. The pricing policy also allows for sufficient margins for retailers so that they can provide the generous customer service, in-store ambience, and shopping amenities that are synonymous with the Brighton brand.7 It is so committed to this approach that when tiny Kay’s Kloset in suburban Dallas insisted on discounting the line and took Brighton to court, the company fought back. After the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled in Kay’s favor, citing decades of precedents, the company appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which sided with Brighton’s point of view.

In so doing, Brighton changed the landscape of American retailing: The decision overturned a ninety-six-year-old piece of the Sherman Antitrust Act and told courts that manufacturers and distributors sometimes could, in fact, insist on minimum prices, so long as the effects of such policies, as in Brighton’s case, are pro-competitive.8 Although the company has grown considerably since then and now includes more than 160 company-owned Brighton Collectibles stores, maintaining minimum retail prices on its goods remains a cornerstone of its strategy.

To begin to capture these decisions and the role they play in Brighton’s system of value creation, or what Young likes to call “the secret sauce,” we could make a list of the company’s various operations and how they work in concert to support the company’s purpose. For instance, the trips with boutique owners and the full-price policy are key parts of the company’s marketing efforts. The product range, sales and distribution channels are part of the system too, as are the company’s information technology systems, operations, human resources, and finance functions. They all support the same goals with activities that are consistent and specific to Brighton’s approach.

THE STRATEGY WHEEL

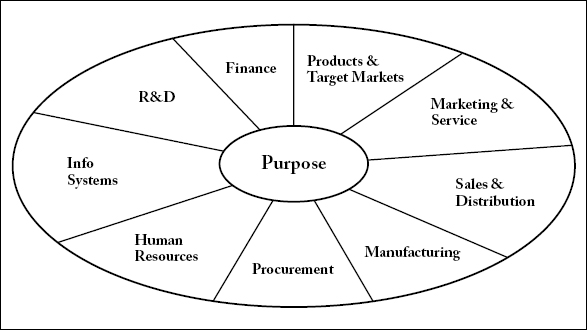

To visualize and record how a system of value creation backs up a firm’s purpose, I use a time-honored approach that has come to be known as a “strategy wheel.”

As we saw in the Gucci case in chapter 5, the strategy wheel provides a picture of how you will win. The purpose in the center says why you exist—what you do differently or better than others—and the unique configuration of activities and resources around the rim shows what will enable you to deliver on that promise. Brighton’s strategy does this well.

Each system of value creation, and thus each strategy wheel, will be different, because every organization has its own purpose and unique set of activities that drive that purpose. Even the headings around the rim will differ across firms—for example, while R&D will be important in one firm, in another it wouldn’t even appear on the wheel.

The point of this work isn’t about “checking boxes” or “getting all the way around the wheel.” It’s about spending time thinking about your business and challenging yourself to see what’s really there—and even more, envisioning what could be there. Just penciling in what you do in finance, human resources, R&D, or any other function in a mechanical way isn’t likely to be helpful; identifying a bunch of plain-vanilla activities around a plain-vanilla purpose won’t leave you any better off than you are today.

Rather, when it works best, the process is a lot like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. Each piece must work with the others, coming together to create a picture of what your business can be. The real work and the real payoff come when you’re assertive, when you push the envelope and ask: What would winning really take? How could this element do more for us? What could we do differently if we narrowed our focus to one type of target customer? Gradually, as you define and refine, you should begin to identify not just what you do better and worse than the other guy, but what aspects of your company—from your customer base to what you do for them—make you different, and truly give you an edge, or could do so.

As Philippine entrepreneur Amable “Miguel” Aguiluz IX developed his strategy wheel, he began to see his business in a holistic way. In 2002, Aguiluz started Ink for Less to provide a cheaper alternative to OEM printer cartridges—sorely needed in a country with per-capita income of roughly $2,600 at the time. Today the company sells a vast variety of ink and toner cartridges, toners, do-it-yourself refill kits, continuous feed systems, and related products and services. The dominant supplier in the Philippines, Ink for Less has more than 600 outlets and an expanding franchise operation.

At the center of Aguiluz’s strategy wheel is this well-crafted and clear purpose: “Readily available and reliable 100% quality ink refills and service at competitive prices.” Building the system around it led him to reconsider how every element of the business could contribute to the whole. Pricing, of course, is crucial. His customers currently might pay $6 to $8 to refill a $25 or $30 cartridge or about $16 to refill a $75 toner cartridge. So Aguiluz pays special attention to elements, such as logistics, that affect his costs. His people scour the region for quality inks at good prices. “When I started, I was buying bottles of ink,” he says. “Now I am buying fifteen tons of ink per month. That shows you the power of volume I can command with my suppliers.” Sales costs are important, too; Aguiluz works hard to keep them in the single digits. This discipline around costs has given him the flexibility to drive his prices lower to respond aggressively to competitive threats. When a franchisee of an Australian chain came into his market, for example, he was able to respond by dramatically lowering his prices at nearby stores.

Refilling ink cartridges isn’t an especially high-tech operation. Nevertheless, Aguiluz realized that research and development had to be a cornerstone of his strategy. Without it he wouldn’t be able to stand up to the printer manufacturers, or contend with mom-and-pop competitors, who might charge less than he does. For example, printer manufacturers try to foil ink refillers by continually redesigning cartridges and changing where they hide the entry holes. In response, Aguiluz’s R&D crew buys every single printer and every single cartridge as it comes to market so they can reverse-engineer them and figure out how they work. When printer makers added a chip that shuts down the printer if the cartridge isn’t new, his R&D people worked with their suppliers around Asia to learn how to add a counter-chip so that the refilled cartridge would work. These efforts not only keep Ink for Less in business, they enable it to provide better service than less sophisticated players. Bulletins and videos are sent regularly to the stores, alerting outlet managers and technicians to new cartridges and new processes, so that nothing customers bring in will stump them.

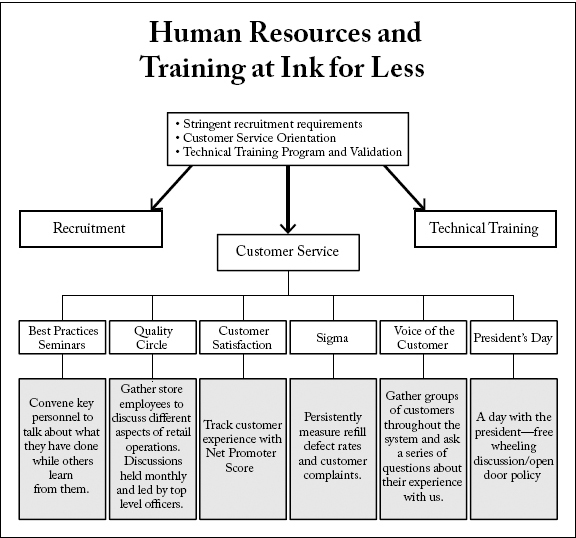

Over time, Aguiluz and his staff have built out cascading sets of activities for every spoke on the wheel (see, for example, Human Resources and Training). They revisit them frequently to make changes that help Ink for Less maintain or increase its lead in the market. Aguiluz often returns to the strategy wheel on his own—sometimes spending a full day working through the implications of a particular action, such as a pricing change, going from spoke to spoke to see what adjustments need to be made to keep the wheel in alignment.

His rigor pays off. In 2008, the Philippines Junior Chamber International named Aguiluz its “Creative Young Entrepreneur” of the year. Over the last nine years, Ink for Less’s sales have grown at an average annual rate of 15 percent, and profits have grown even faster. But Ink for Less is not only capturing value for itself; it is making its customers better off than they would have been if the firm weren’t there.

REALITY CHECK

You will likely have to make a number of assumptions in building your wheel. Check them carefully! People in all professions go astray because they’re operating on untested assumptions. In strategy, these are often a recipe for disaster. Be ruthless in challenging what you think you know.

It’s particularly easy to make this mistake when it comes to the linkage between your stated purpose and your system of value creation—is it really designed to do what you say, and is it working? Too often, I’ve seen executives claim their companies are high-end, differentiated companies seeking to make a difference by offering customers not lower prices, but better-than-average goods. They have everything lined up—except customers who share that view and are willing to pay a premium for their products or services. Remember how Maurizio Gucci staked the company’s future on top-of-the-line products that customers stayed away from in droves? The linkage simply wasn’t there.

To assess whether what you are doing is working, you need to look for the data and the facts, and not just rely on intuition. What evidence do you have that you are the low-cost provider or the premium producer you say you are? Where, exactly, in the process do you add value? Can you support that view with facts—internal process measures of key performance drivers, and outcome measures like sales results, profit margins, market share, or return on investment?

Consider how Walter de Mattos does this. A longtime Brazilian journalist, he founded Lance! Sports Group in 1997 to capture his fellow sports fans’ obsession with their favorite soccer teams. Since then it has grown from a daily sports newspaper in two cities to five more editions plus magazine, television, mobile, and Web versions that give Lance! a national platform and make it the largest sports news organization and leading authority in Brazil.

Embedded in de Mattos’s strategy wheel is a self-reinforcing system of elements: Multitask journalists provide unique content to a variety of platforms, driving readership. Large readership, in turn, brings in regional and national advertisers. Both the depth and breadth of soccer coverage and the size of the circulation serve as barriers to entry, making it harder for competitors to make inroads. To focus resources on his strengths and manage costs, he outsources distribution of the print newspaper and works with an external design firm.

De Mattos assesses whether the individual parts of the system are working, and in sync, by looking at specific, tangible results: estimated readers per week (2.3 million in 2011); unique website visitors (750,000 a day, some of whom check the site more than once); and cost per story (lower than a pure television producer or newspaper publisher because content is shared across the Web, print, and video outlets). Over the last five years, these collectively gave Lance! one of the highest rates of growth and return on investment among Brazilian media companies.

What do your metrics tell you about your strategy? Are they consistent with your rhetoric? Do they show that you are winning with your plan?

PULLING IT ALL TOGETHER

After you’ve identified your purpose, aligned your activities and resources, and tested the results—all internal working steps—you are ready to summarize your strategy in a statement you can use to communicate that commitment both inside and outside your firm. You don’t need to use formal language or any particular format; the most important goal is conveying your unique aspects and advantages with specific and engaging words.

Here are three examples of memorable strategy statements from well-known organizations. Can you tell who they are?

A hotelier:

________ is dedicated to perfecting the travel experience through continuous innovation and the highest standards of hospitality. From elegant surroundings of the finest quality, to caring, highly personalized 24-hour service, ________ embodies a true home away from home for those who know and appreciate the best. The deeply instilled ________ culture is personified in its employees—people who share a single focus and are inspired to offer great service.

Founded in 1960, ________ has followed a targeted course of expansion, opening hotels in major city centres and desirable resort destinations around the world. Currently with 75 hotels in 31 countries, and more than 31 properties under development, ________ will continue to lead the hospitality industry with innovative enhancements, making business travel easier and leisure travel more rewarding.9

A magazine:

Edited in London since 1843, ________ is a weekly international news and business publication, offering clear reporting, commentary and analysis on world current affairs, business, finance, science and technology, culture, society, media and the arts. As noted on its contents page, ________’s goal is to “take part in a severe contest between intelligence, which presses forward, and an unworthy, timid ignorance obstructing our progress.” Printed in five countries, worldwide circulation is now over one million, and ________ is read by more of the world’s political and business leaders than any other magazine.10

An accompanying document describes its editorial policy, including its fierce commitment to independence and its practice of being written anonymously, with no bylines, to make it a paper “whose collective voice and personality matter more than the identities of individual journalists.”

A nonprofit:

________ is an international medical humanitarian organization created by doctors and journalists. . . . Today, ________ provides independent, impartial assistance in more than 60 countries to people whose survival is threatened by violence, neglect, or catastrophe, primarily due to armed conflict, epidemics, malnutrition, exclusion from health care, or natural disasters. . . . ______ also reserves the right to speak out to bring attention to neglected crises, challenge inadequacies or abuse of the aid system, and to advocate for improved medical treatments and protocols.11

You probably recognize the Four Seasons Resorts, the Economist, and Doctors Without Borders from language that is closely linked with them, like “highest standards of hospitality,” “contest between intelligence and ignorance,” and “independent, impartial assistance.” Beyond that, though, are prescriptive elements that define their advantages, describe what they stand for, and tell you something important about how that work will be done.

There are plenty of hotels around, for instance, but Four Seasons defines its service culture as a unique attribute that gives it a strategic difference. There are plenty of magazines as well, but many are languishing while the Economist, with its fierce independence, incisive commentary, and timely reporting, gains ground. The Doctors Without Borders statement makes clear that the Nobel Peace Prize–winning organization doesn’t just provide impartial medical assistance; it also advocates for change.

To break the process down further, a good strategy statement articulates a company’s purpose, its means of competition, and its unique advantages by answering the most basic questions about what a company does and how it does it:

• Who we serve

• With what sort of products or services

• What we do that’s different or better

• What enables us to do that

And it has these qualities:

• It is reasonably short and parsimonious.

• It is specific.

• It states what the company does and why it matters in a way that anyone can summarize without having to quote it literally.

• It avoids jargon, such as “best of breed,” “best in class,” or vague words such as superior, expert, and empowered.

• It is affirming, but not grandiose or self-important.

• People easily recognize that it’s you.

The statement should be brief because brevity forces you to get to the very heart of what you want to say without larding up your description with empty words or superlatives. Make every word real. Make every word count. Long sentences and vague language can obscure your effort to describe what’s really important. At best, they’re unhelpful; at worst, they’re potentially misleading and distracting.

If you feel your company’s strategy is too complex to summarize in one or two paragraphs, that’s likely a sign that the strategy itself is unclear, or convoluted in some way.

There is no question that keeping the statement short and to the point is hard work. When an editor once asked Mark Twain for a two-page short story in two days, Twain replied with only mild exaggeration: “No can do 2 pages two days. Can do 30 pages 2 days. Need 30 days to do 2 pages.” Even if you aren’t very wordy, you’ll find that a good brief statement takes revision and polish.

The goal, moreover, is not to write a statement that sounds good: It’s to write a statement that is good, that really captures your company’s distinctiveness. Once you’ve written and rewritten it, shop it around. Don’t show it just to those who work for you or know the business well; give it to acquaintances who don’t really know what you do. Ask people to rephrase it in their own words. And don’t be surprised if what’s mirrored back to you isn’t what you intended. That’s helpful feedback. Your strategy statement should be able to travel on its own—without interpretation and without you there to coach the reader (or the employee, customer, banker, or casual visitor to your website) on what it “really means.”

Here’s the strategy statement constructed by de Mattos for Lance!

To be the prime source of 24-hour-a-day vibrant sports news targeting an audience of passionate, young, male Brazilian sports fans by:

• Employing 300 sports multi-task journalists to provide exclusive content;

• Using the most current technology to deliver content across the widest number of media platforms (print, web, mobile, WebTV and web radio);

• And using compelling design to enhance all Lance! products;

• All under a powerful core brand, Lance!

• As a means to become one of the most profitable Brazilian media groups as measured by ROI.

And this, in a very different voice, is how Aguiluz constructed the strategy statement for Ink for Less:

Ink for Less aspires to be the largest and most profitable professional ink refilling business by providing

• The best and latest ink refill quality and service

• At reasonable prices

• To our quality conscious but price sensitive individual computer users and small and medium scale business and government institutions

• Through conveniently-located ink refilling stations throughout the major cities and key towns in the Philippines and the rest of Asia.

If you’re frustrated with your strategy or with your statement, keep at it. Writing a bad strategy statement is often the necessary prelude to writing a good one. Often what’s required is not just wordsmithing—it’s “strategy-smithing”—because what you want is a strong, meaningful strategy, not just pretty words. As with many kinds of writing, the words themselves usually aren’t the problem; the challenge is the thinking that goes behind them.

Hallmarks of Great Strategies

Anchored by a clear and compelling purpose

It is said that “if you don’t know where you’re going, there isn’t a road that can get you there.” Organizations should exist for a reason. What’s yours?

Add real value

Organizations that have a difference that matters add value. If any of them were to go away, they would be missed. Would yours?

Clear choices

Excellence comes from well-defined effort. Attempting to do too many things makes it difficult to do any of them well. What has your business decided to do? To not do?

Tailored system of value creation

The first step in great execution is translating an idea into a system of action, where efforts are aligned and mutually reinforcing. Does this describe your business? In most companies, the true answer is no.

Meaningful metrics

Global outcome measures like ROI indicate whether a strategy is working, but key performance drivers, tailored to your own strategy, are a better indication. They break big aspirations into specific, measurable goals, and guide behavior toward what matters.

Passion

It’s a soft concept, but it’s at the heart of every great strategy. Even in the most mundane industries, companies that stand out care deeply about what they do.

THE ROAD AHEAD

This exercise should have clarified your thinking and given you an objective, hard look at your business.

If you’ve been honest with yourself, your thoughtful analysis will likely have brought to the surface problems that should be fixed or areas that require new attention—the bread-and-butter work of a leader-strategist. Some of the problems may be serious: You may need to reconfigure parts of your organization, or find new ways to distinguish yourself. In the worst case, you may have come to the painful realization that you should exit part or all of your business. This can be especially hard when it’s close to your heart for one reason or another.

Kerr Taylor had to confront such an issue when he reevaluated his real estate business in the Great Downturn of 2008. Years before, when the company was too big to rely on friends and family but still too small to tap institutional investors, he set up a broker-dealer to help fund real estate purchases. He got the appropriate securities licenses and sold interests to investors, funding the first $25 million of the company’s growth. “I couldn’t find another way to do it,” he says.

Like many companies, AmREIT had to cut back when the economy turned sour. By then Taylor had successfully raised money from the public and through big financial companies, and the broker-dealer no longer offered the company a strategic advantage. Further, the funds needed to operate it could be put to better use. Even so, he was still emotionally attached, “because it was what had brought us along.”

The downturn and the experience of clarifying his company’s strategy finally pushed him to shut the business down. “It was one of the hardest things I ever did,” he says. “That came out of this journey . . . and it’s still scary. But it made us grow up.”

The process can also strengthen new strategic thrusts, as Miguel Aguiluz discovered. After a number of big businesses asked him for an ink refilling program, he came up with a plan for Ink for Less Professional. Initially he was tempted to simply tack it on to Ink for Less as a “by-the-way” business. But on reflection, he concluded that if he didn’t create a whole new system around it, any competitor who came in after him and focused exclusively on business customers would quickly undercut him.

Telling Your Story: Mistakes Strategists Make

Carefully honed strategies and the statements that capture them set direction, establish priorities, and guide activity with a firm. They also help you communicate your story externally. Weak strategies and weak statements do the opposite. Avoid these pitfalls.

1. Generic statements

Simply saying you are in book publishing, steel fabrication, or sports marketing tells little. Within that domain, what makes you distinctive? Ask yourself this: If they read your strategy statement, would your customers recognize you? Would your employees? Pixar didn’t say it made movies—it said it developed “computer-animated feature films with memorable characters and heartwarming stories that appeal to audiences of all ages.”

2. No trade-offs

You can’t be everything to everybody, although a lot of weak strategies and strategy statements implicitly claim to be. It doesn’t work.

3. Empty clichés

Grand statements unsupported by credible detail are vacuous. Terms such as “Excellent,” “Leading,” and “Outstanding” don’t say anything specific. Strategy statements gain credibility when specific statements capture what a firm does particularly well.

4. Forgetting the means

Many weak statements eagerly tell you the what but forget the how—the critical activities and resources that enable the firm to realize its competitive advantage. It is through the how that a reader gains confidence about what you’re doing. Which do you find most convincing: “We’re the low-cost producer,” or “We’re the low-cost producer operating the world’s largest titanium dioxide plant utilizing DuPont’s proprietary technology”?

5. Leaving out the customer

Who you serve is a crucial part of your story. It not only defines your playing field; it also says who will ultimately decide whether what you do really matters.

6. Deadly dull

There is no other way to say it: A lot of strategy statements in their initial drafts drone on, without conviction, without inspiration. Ask yourself: Would you want to work for this company? Would you want to buy from it?

This insight came to him as he worked his way through an initial strategy wheel for Ink for Less Pro: The activities in the spokes and some of the spokes themselves were markedly different from his consumer business. Employees would have to look more professional, wearing neckties, for instance. He would need to offer new payment terms, to sync with company procurement systems. To provide great service (and create a difference), he determined, each customer should have a “standby refilling technician,” to be available when needed. As a result, the products and services would be priced differently. And he wanted to create another market advantage by giving companies printers for free in exchange for a two-year ink contract, not only covering his equipment costs but also keeping competitors at bay. The Pro business is now launched and growing.

This way of thinking has become second nature for Aguiluz. “It’s not just for books,” he says. “Every time I think of a new business, I really do the strategy wheel,” to understand “how I can develop my advantage.” As his businesses change or face new competition or other challenges, he goes back to the wheel and examines the whole system, recognizing that a significant change in any part of it is likely to have implications for the rest.

Indeed, when the process works best, a well-defined strategy is like the North Star, guiding you in the right direction no matter which way the competitive winds are blowing. At Lance!, Walter de Mattos has found that strong market share and sizable margins haven’t protected the company from competition on all sides. The World Cup is heading to Brazil in 2014, and the country will host the 2016 Olympics, both of which should be a dream opportunity for Lance!—except that the events have spawned new coverage from a number of new players, all competing for the same advertising dollars.

Habits are changing, too. His business was built on quality work produced by a team of specialized journalists. As he watches readers peruse the Internet, de Mattos said, “people are going to seven or eight media outlets in the space of ten minutes,” reading so many different short stories that they can’t remember what they read or where they read them. “When you see things like that, you have to question your beliefs” about what kinds of information people want, he said. “I have been questioning my beliefs very much lately.”

There is “a lot of temptation to change your strategy when something like that happens,” he said, but he doesn’t think a fundamental change is called for. Instead he is fine-tuning what he calls “gaps” around the wheel in finance, human resources, and technology to strengthen Lance!’s capabilities. The firm remains committed to being the prime source of sports news for Brazil twenty-four hours a day, over all kinds of media platforms.

Your strategy, too, if it is well conceived and on point, will guide you through tumultuous markets, competitive challenges, and your push into new arenas. It will tell you what resources you need to build up and what baggage you should let go. More fundamentally, as you put purpose in the center of your strategic thinking, you will see a shift in the way you look at every opportunity. You will find yourself instinctively asking whether that new business, customer, or product adds value, whether it really fits with what you are doing, and whether it benefits from or enhances the business as a whole. Only then will you truly own your strategy.

Even so, you will continually have to adapt. Shifts in the economy, in your industry, or in your own shop may force you to reconsider your approach and maybe even reinvent it. As we will see in the next chapter, that’s why the job of the strategist is never really finished.