In the summer of 2014, New Yorkers started to notice a new presence on the Midtown skyline: 432 Park Avenue, an unrelenting concrete grid of ten-by-ten-foot openings stacked like cubbyhole units. Unpromising buildings under construction were nothing new, but this one just kept getting taller and taller, adding a new floor every week. By fall, it spindled far above the tallest part of the city, dwarfing even its Fifty-seventh Street neighbor, One57. Only a few months earlier, that brand-new thousand-footer had seemed monstrously tall, but compared with 432 Park it shriveled into insignificance. Suddenly you could see the 1,400-foot rod of 432 Park from almost anywhere, dominating the city’s silhouette as forcefully as a campanile looms over an Italian hill town.

A bell tower performs many tasks: It projects the spiritual and worldly power of the Church, calls the faithful to Mass, announces feasts, mourns deaths, keeps time, and acts as a unifying symbol of community. The Park Avenue apartment tower, on the other hand, represents only its investment value. It’s hardly even a place to live, only an extremely expensive safe-deposit box where the global ultra-rich can quietly park their cash. The design, by Rafael Viñoly, looks like the product of rationalism gone insane, a linked chain of tic-tac-toe games reaching into the sky. Some architects love it for that reason. Making a large and complex structure look this simple is a staggering task. The result eventually placated me, too. I have grudgingly started to appreciate its rigor and lack of showiness and the fact that it’s the rare new tower that isn’t curtained in glass. As the building grew, it grew on me. Perhaps today’s children will one day consider it a landmark, not to be tampered with. Every iteration of the New York skyline is an abomination to one generation and an inspiration to the next.

432 Park Avenue redefines the Midtown skyline.

Not since the days of Art Deco has New York experienced a growth spurt like the one that’s stretching it now. Burly office towers have begun to crowd Manhattan’s once low and open West Side. The newest downtown skyscrapers push over the tops of slightly older skyscrapers. Thousand-footers may soon pop up in Brooklyn and Jersey City, New Jersey. In Midtown, Viñoly’s colossus will soon get more company, too.

Why do these new buildings have to be so tall? For starters, because a skyscraper is a money machine. It’s what happens when a team of developers, cost analysts, insurers, engineers, architects, brokers, investors, and lenders makes a collective determination that physics and market forces, fused into one enormous hunk of a building, will probably yield a profit. But that’s only part of the story. When buildings consist of nothing more than the output of bookkeepers’ jottings, then every effort to maximize profits yields the same result: a maxed-out skyline of utter monotony.

Fortunately, in high-stakes construction, pragmatism has its limits. Profit-and-loss calculations can never quite account for a set of deeply irrational instincts, which is why some of New York’s tallest towers soar well above the point of diminishing returns. The Rutgers economist Jason Barr has quantified the “status effect”: how much higher some skyscrapers rise than the profit motive would justify. The Empire State Building, Barr estimates, is fifty-four stories taller than pure number-crunching suggests it should be. The race to erect the world’s tallest skyscraper endowed the Chrysler Building with thirty-seven extra stories and its rival, 40 Wall Street, with twenty-nine. Barr doesn’t follow his reasoning to the logical conclusion: If the single-minded pursuit of profit ruled alone, we would have a stumpier city.

Thank goodness, then, that greed is not the only source of the skyscraper’s addictiveness; so is the primal urge to climb and stare at a more distant horizon. That drive intensifies at certain times, and those variations get mapped onto the skyline. After periods of stasis, the spiritual lust for height returns, producing an ever more spectacular urban silhouette, a dynamic work of collective genius. There’s something sublimely crazy about this cycle. Builders keep building because they believe, sometimes foolishly, that even if a project makes no economic sense at the moment, it will pay off someday. To erect a tall building is to proclaim one’s faith in the future, and the skyline embodies that confidence multiplied many times over. It’s a seismograph of optimism.

The results are not always inspiring. All through the twentieth century, Manhattan grew by dint of ugly architecture, punctuated by the occasional marvel. Every celebrated skyscraper rose amid bundles of mid-rise mediocrity. Each masterpiece-producing boom also threw off acres of stupefying repetition. It’s an old story. Once again, a new generation of towers is crowding out the sky and shadowing our open space. Their domineering mass can kill street life and choke off the smaller-scale city at their feet. They dump more hordes on crowded subway platforms. Today’s juggernauts block our view of yesterday’s juggernauts: We are losing sight of our icons.

Some of these are practical objections, some selfish. But if many New Yorkers see each new tall building as another oppressor, it may be that their reaction is partly visceral, an instinctive revulsion couched in complaints about traffic, construction noise, and neighborhood character. The writer W. G. Sebald attributed a deep-seated fear of enormousness to the title character of his 2001 novel Austerlitz, and described it as practically a law of nature:

No one in his right mind could truthfully say that he liked a vast edifice….At the most we gaze at it in wonder, a kind of wonder which in itself is a form of dawning horror, for somehow we know by instinct that outsize buildings cast the shadow of their own destruction before them, and are designed from the first with an eye to their later existence as ruins.

These days, you can see that bleak process play out again in Downtown Brooklyn, where canyons of cheap window walls and protuberant air conditioners rise along Flatbush Avenue. It’s hard to fathom how sentient beings could have devoted so much time, money, and enthusiasm to producing such drear. Well, not that hard: Everyone follows the path of least resistance and then moves on to the next job. The result is an orgy of indifference. When a newcomer does sport a dash of design, it only accentuates the sadness. Consider Brooklyn’s temporarily tallest building, 100 Willoughby Street, a.k.a. the all-rental AVA DoBro, which SLCE “designed” for AvalonBay. The architects couldn’t do much about the monolithic mass, but they did speckle the façade in an assortment of blue panes, so that it looks as though the builders had raided an odd-lot store. (Blue-glass patchwork has become a mystifying mini-trend.)

And yet, once again, massed ghastliness could also give birth to a masterpiece: the future tallest tower in Brooklyn. The Williamsburgh Savings Bank held that title for eighty-five years, before being deposed by a series of unworthy successors. Happily, the next claimant, a thousand-foot tower at 9 DeKalb Avenue, designed by SHoP Architects, could be one of the most sensitively detailed and spectacularly expressive additions to the New York (not just Brooklyn) skyline since the Seagram Building. Most towers grab height; this one earns it.

Like most great urban architecture, the design emerges from a thicket of local constraints. The scarcity of lots, and the difficulty of assembling them, forced SHoP to squeeze its seventy-three-story spire on a triangle it shares with an unofficial landmark, Junior’s Cheesecake, and the officially designated Dime Savings Bank. The bank, originally designed by Mowbray & Uffinger in 1906, expanded in 1932 into a geometric layer cake: a round cupola on a hexagonal base, enclosed by another hexagonal banking hall, inscribed in a triangular site. SHoP’s designers extended the same grid onto the adjacent lot and massaged it into a composition of nested and overlapping hexagons. The faceted forms get smaller on their way to the top, like a bundle of pencils of varying lengths. From below, the arrangement of staggered setbacks and vertical piers evokes an abstracted sandstone butte, gorgeously scored by erosion.

Despite the Western allusion, this is unmistakably a New York building—or will be, if it gets built the way it was designed. Tubes of varied sizes and profiles run up the exterior like crazy organ pipes, growing thicker and darker as they shoot into the sky. The tower doesn’t pretend to dematerialize in a cloud of light, mist, and glass, as so many clunky supertalls wish they could. Instead, virtually every vantage point reveals multiple façades, all of them textured and sinewed. An assortment of dramatic flourishes—the chiaroscuro of blackened metal and brazen glints, the Batman-ready ledges, the syncopated rhythms of windows, the spiky crown—add up to a new kind of Gotham Gothic.

These charms may not be enough to placate Brooklynites who fear that giants are trampling their borough. When 9 DeKalb Avenue opens, its thin-air penthouses will look out over a four-to-eight-story borough stretching from Newtown Creek to Coney Island. What is to prevent one super-scaled building from leading to the next, until they invade the leafy brownstone shires? Plenty, for now: zoning regulations, the distribution of subway lines, the existence of historic districts, and the power of money to fight money. These barriers can crumble, though, and so the best way to preserve low-rise Brooklyn is for Downtown to succeed by growing up rather than out. A great skyline remains concentrated and confined, its towers made meaningful by borders, its scale a contrast to be savored, not feared. Height is not in itself a problem. Managed well, it opens the way for a constantly growing but geographically confined metropolis to expand. New York reconstitutes itself all the time, nourished by a regular supply of invention, and the day we consider the skyline complete and untouchable is the day the city begins to die.

Taller buildings won’t ruin New York, but too many terrible ones can. We need the exceptions, the Empire State and Chrysler Buildings, designs that captured the imagination before they could turn a profit. When you’re putting up a multibillion-dollar tower that’s a quarter mile high, it had damn well better be a work of art. That’s a challenge: Overweening realities of technology, zoning, and real estate arithmetic don’t leave much leeway for frills like beauty. The difficulty of making an elegant, symbolic presence out of an immense vertical structure has been vexing architects since the beginning of the skyscraper age.

“Problem,” declared the great architect Louis Sullivan in 1896: “How shall we impart to this sterile pile, this crude, harsh, brutal agglomeration, this stark, staring exclamation of eternal strife, the graciousness of those higher forms of sensibility and culture that rest on the lower and fiercer passions?” Sullivan knew from experience that in large, expensive buildings, aesthetics struggle to assert themselves.

The earliest skyscraper designers groped toward a way to translate traditional opulence into a vertical style. They enlarged European precedents, piling up palazzos and cathedrals into layered buildings encrusted with giant cornices, columns, and pediments. Sullivan’s generation divided the tower into three parts of varying symbolic significance: a column’s base, shaft, and capital; a tree’s roots, trunk, and branches; a drama’s exposition, denouement, and conclusion. Sullivan saw the three parts as the natural, and therefore excellent, consequence of the job a building does: high-ceilinged shops on the bottom, in the middle a warren of offices repeating as many times as necessary, topped by a windowless attic housing mechanical systems. “Form ever follows function,” he declared, a formulation slightly less terse and much less stylistically prescriptive than the modernist battle cry it engendered: Form Follows Function!

In recent years, that imperative has yielded two comically distinct types of glass super-skyscrapers: the fat office building, with a girth ample enough to accommodate a trading floor; and the skinny residential shaft, just thick enough for a full-floor duplex. Think of them as architecture’s Laurel and Hardy.

Today’s urban workplaces have little to do with the elongated masonry pyramids of the twenties or the spare blocks of the sixties. In the new business behemoths—the Bank of America Building at One Bryant Park, for instance—a few indentations or judicious asymmetries set off tautly seamless skins. Vertical folds in a curtain wall resemble slits in a satin gown worn by an elephant. These are not so much whims of style as they are forms shaped by technology and the demands of the most valued tenants. The corporate culture shaped by financial firms dictates the need for enormous, column-free floors and high ceilings. Large, populous floor plates mean more high-speed elevators, which get packed into a thicker concrete core. Glass walls keep the inner cubicles from feeling sepulchral. Office towers’ most dramatic advances take place in their innards: You can practically date a skyscraper’s vintage by the air quality in its offices, the speed of its elevators, and the softness of its lighting. These features also affect the building’s mass. Contemporary air-conditioning ducts take up space between floors, meaning that eighty stories need a lot more height than they once did. Unsentimental efficiency is raising a crop of ungainly monoliths.

Sullivan assumed that only the office building warranted great height, but the most radically double-edged innovation of recent years is actually the ultra-tall residential tower. If you’ve ever gazed southward across Sheep Meadow in Central Park, you know that the plutocratization of the skyline has gotten under way. Along Fifty-seventh Street, lanky residential towers are lining up for Central Park views like an NBA team craning to peer at a new iPhone. From each $100 million penthouse, the park looks virtual and screen-like, a glossy rectangle of green, populated by tiny avatars. Between 432 Park Avenue (at Fifty-sixth street) and One57 (at the corner of Fifty-seventh Street and Seventh Avenue), the gracious old building that for ninety years was known as Steinway Hall, where Carnegie Hall performers came to choose their pianos, is getting a new identity and a new neighbor: 111 West Fifty-seventh Street. There’s hope for that one: the old foyer and showroom will become the building’s lobby, which SHoP has adorned with a bronzed feather of a tower, tricked out with glazed terra-cotta tiles. But the supremacy of 432 Park will last only until the completion of the Nordstrom Tower, near Broadway, a 1,550-foot scene-stealer by the supersizing virtuosos Adrian Smith and Gordon Gill. (They also designed the world’s currently tallest tower, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai.) When it’s done, the Nordstrom Tower will clear the top floor of One World Trade by a healthy margin.

I evaluate tall buildings not stylistically, or by how well they serve those who pay the bills, but by how sensitively they integrate the different spheres of interior, street, and skyline. A few residents occupy a tower that tens of thousands walk by every day and millions see from all around. Those separate scales impose different aesthetic demands, all equally important. It used to be a given that a great building met its private and public responsibilities with equal panache. But because today’s economics permit a tiny number of largely absent people to have a disproportionate impact on the skyline, these buildings invert the rationale that propelled skyscraper construction for more than a century. Instead of packing the largest number of people onto the smallest patch of earth, they fill up the skyline with sparsely populated habitats for oligarchs who, if they live there at all, roam across their parquet tundra, hollering for their mates.

Yet it’s not enough just to gape at these towers’ bravado or grumble at the arrogance of the hyper-rich gobbling up the sky. Like it or not, the elongated condo is an ever-more-assertive category of New York architecture, and it, too, can function as a form of public art. The combination of slenderness and height means that skyscrapers can sprout from modest lots, minimizing their impact on the street and narrowing the shadows they cast. The fact that they contain the caviar of real estate means that they can afford the luxury of being good. Since we have to live with the follies of the outlandishly wealthy, we should at least insist that they pamper themselves in a way that also enriches the city.

New York’s founding credo is that you get what you pay for, and what you pay for is yours. But in such a dense city, the rest of us also get what you pay for, and we help pay for what you get. A mere $90 million or so buys a nice duplex perch, but the people down below must bear the aesthetic cost—and in some cases the financial cost as well: One57 benefited from an outrageous $66 million tax abatement. In theory, developers pay for their portions of sky and light with architecture worth looking at. In practice, they judge design by their clients’ taste for glitz—which explains One57’s façade, done in fifty shades of azure by Christian de Portzamparc. It’s a luxury object for people who see the city as their private snow globe.

Such buildings fail when they treat New York as an amenity for prospective buyers and the architecture as nothing more than a marketing tool. On the Fifty-seventh Street side, the building pours out of the sky in parallel ribbons that undulate as they fall, then go rippling out above the sidewalk in a wavy canopy. That’s the conceit, anyway. But a building doesn’t liquefy just because computer renderings promise that it will. In the physical world—the one where Hurricane Sandy crippled a crane that dangled perilously on the roof for months—One57 looks like a stolid arrangement of beveled blocks upholstered in silk and satin stripes. Up top, the rounded crown suggests a menacing helmet. It’s as if Darth Vader had dressed up for a charity ball.

Today’s priciest dwellings abound in light and sky, and little else. Through transparent casings, they offer the illusion of levitating just beneath (or sometimes in) the clouds, turning billionaires into creatures of the air. The layouts of these crystalline crows’ nests afford nowhere to retreat from contact with the sky. They offer the fake thrill of exposure but no shelter from the glare. No wonder the owners don’t spend much time there, when they have their choice of cozier homes. And yet builders of super-fancy apartments have nothing else to offer clients that would justify the expense. It’s hard to imagine how high the ceilings would have to be, how glossy the kitchen, or how noiseless the air-conditioning to make an apartment here feel like a good deal. At these financial altitudes, the views are a hedge against the future. If you look out the window and feel like a full participant in city life, then you probably live low enough to have your sunlight blocked by the next round of construction. Billionaires want assurance that that isn’t going to happen.

When I stared out the window of a still-unoccupied eighty-seventh-floor apartment in One57 (asking price $67 million), the city appeared vivid but unreal. My eye drifted to the vague horizon: the shadowy silhouette of the Poconos, the gantries in the Port of Elizabeth, the misty hills of Staten Island, and the low haze of Garden City and the Rockaways. The residents of billionaire aeries are happy to see those places from afar but have little interest in what goes on there. Meanwhile, their actual neighbors’ lives play out at ant level. The hyper-wealthy pay immense premiums to live so high that they can hardly see anything at all.

Why, then, would anyone choose to live atop an observation platform where violent winds make opening a window unwise? For a taste of store-bought divinity. A view is power, a form of majestic surveillance—and you can enjoy it, too.

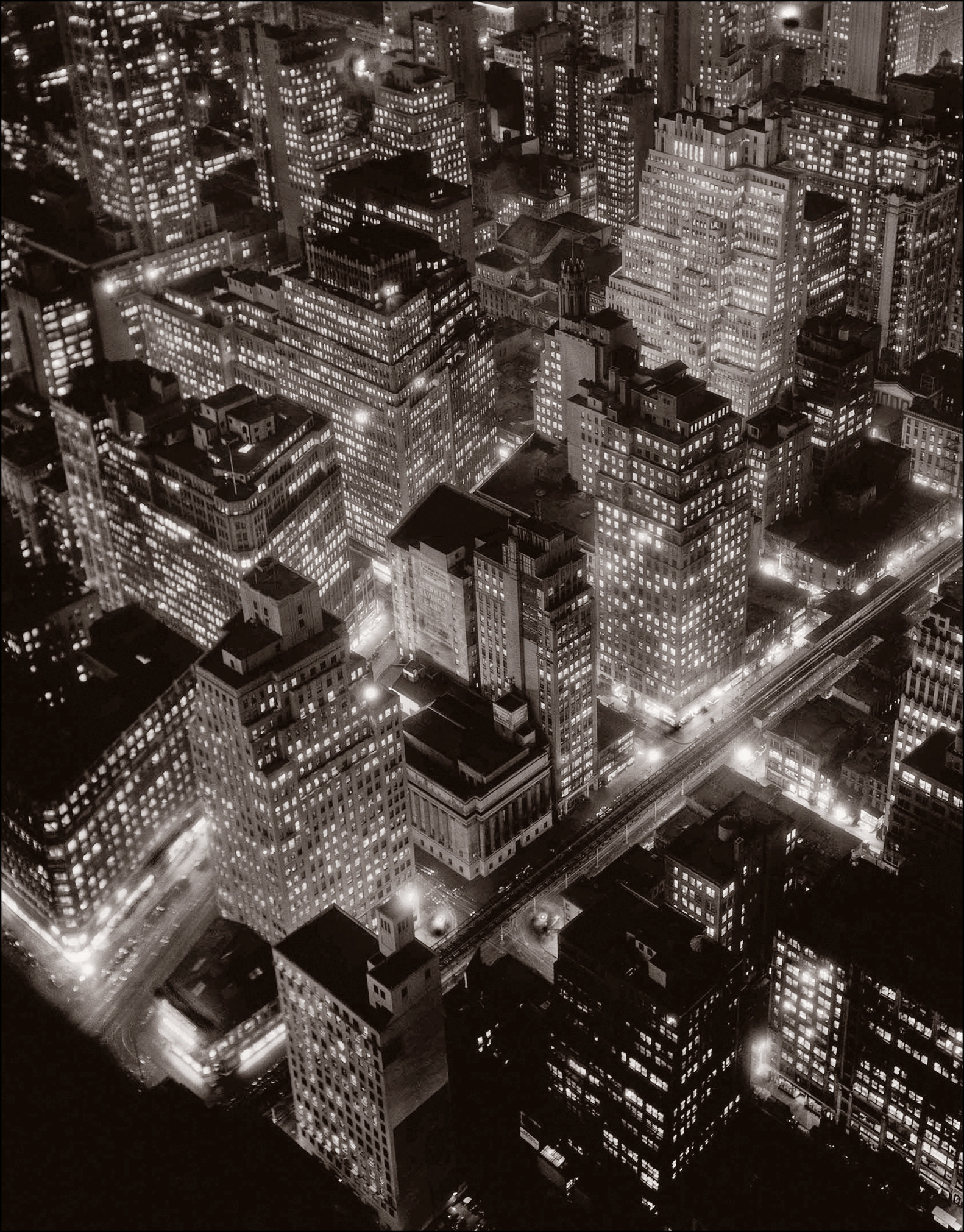

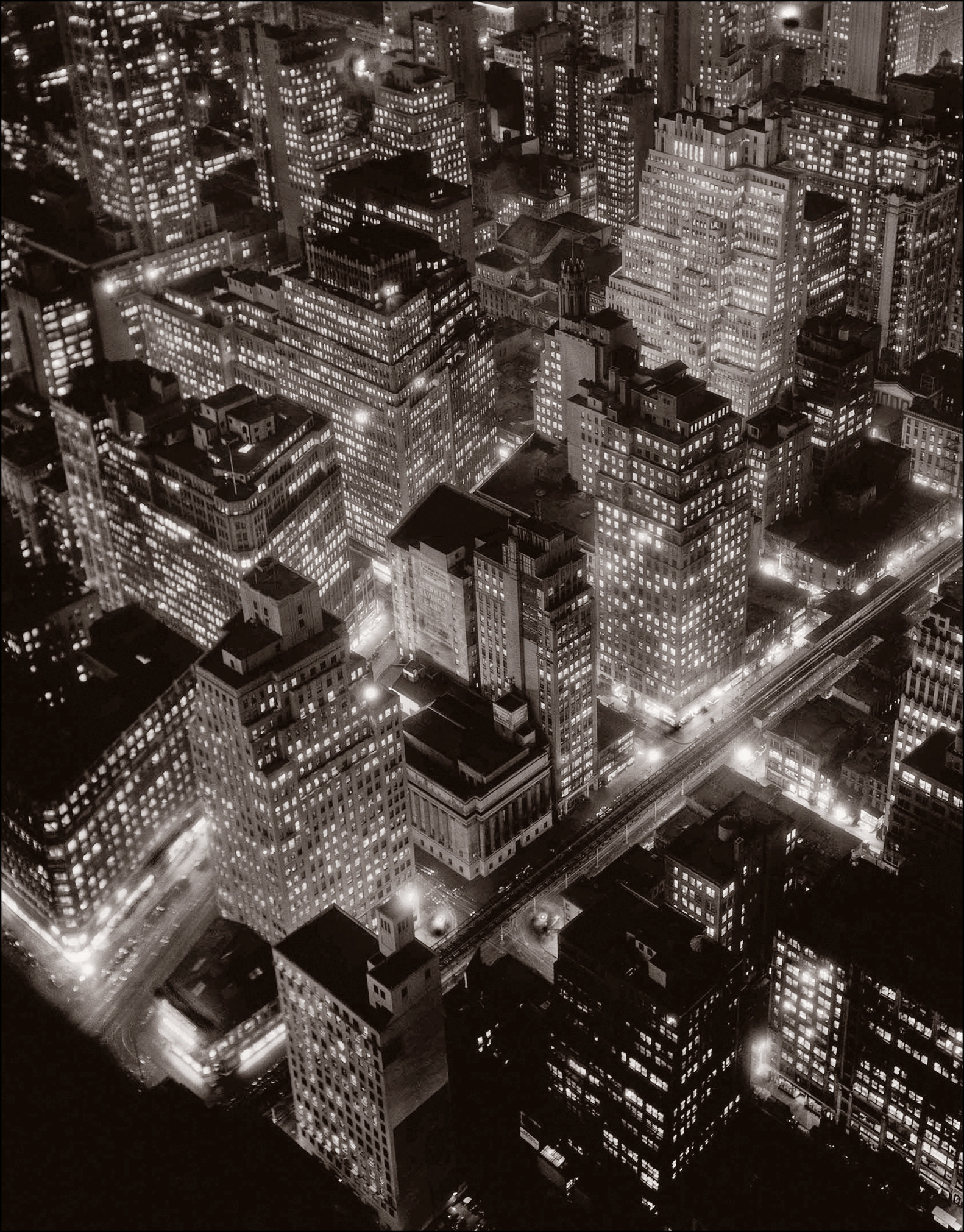

On the dark afternoon of December 20, 1932, the photographer Berenice Abbott took the elevator to one of the highest man-made points in the world in order to chronicle a completely new sight. The Empire State Building was just eighteen months old, and from the eighty-sixth floor Abbott beheld the city of towers from above. She left her shutter open for fifteen minutes during that fleeting stretch between sunset and 5:00 P.M., when she knew that office workers would start to click off their lights. Her wait in the cold, windless air yielded the famous Nightview—the ultimate modern vision, blending stillness and movement, regimentation and sublimity. In the photo, hundreds of foreshortened towers shoot up toward the camera, each one a grid of luminous little squares, each square a person about to go home.

Berenice Abbott, Nightview

I thought of that picture when I stood on the hundredth-floor observation deck of One World Trade Center, where the Empire State Building looks at once immeasurably distant and close enough for me to reach out and snap off its spire. The view is practically astronautical. From here, the city below recedes into abstraction, a gridded 3-D map. The effect is not grandeur but its opposite: The inhabited world has been miniaturized for your viewing pleasure.

To look out over a great, complicated metropolis from this height is to try to give landscape a meaning, to press it into the service of an argument. On the evening after Hurricane Sandy hit, the photographer Iwan Baan went up in a helicopter and took a photo of a stunningly darkened Manhattan, with just one corner incongruously alight. It’s a parable of resilience, the twenty-first-century answer to Abbott’s celebration of modern existence. The bright city may have lost its gleam for a moment, but it will never flare out completely.

If exclusive towers like One57 sell the view as a unique possession, an observation deck rents it by the hour. Legends, a company that manages skyboxes and stadiums and now runs the World Trade Center deck, has turned it into a high-tech spectacular. Before you get a glimpse of an actual place, you follow a winding path through cheesy synthetic bedrock, complete with trickling water, then ride an elevator where a time-lapse panorama zips through four hundred years of New York history—wooden farmhouses giving way to brick, cast iron, terra-cotta, and glass. When you emerge on the hundredth floor, you watch a two-minute multi-screen montage of cabbies, crowds, and subways. Then the curtains lift and—voilà—behind all that razzle-dazzle, spread out before you in its weighty three-dimensionality is…well, on a foggy day, nothing much, actually. But if you have the good luck to visit on a soft, perfect afternoon when a light haze purples the Catskills and flatters the sharp contours of Midtown, then New York looks like a gorgeous stage set. All the theatricals serve to palliate the $34 admission and encourage people to feel they are doing something more exciting than just gazing out the window. They also help distract from the fact that this is what people saw through shattered windows on September 11, 2001, the scene that hundreds jumped into rather than face the flames.

Like a panning shot in a movie, such a godly view creates the illusion of omniscience. In The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, Victor Hugo brings the reader up to the cathedral’s roof to summon a view of Paris in 1482: “The spectator who arrived, panting, at this pinnacle, saw a dazzling abundance of roofs, chimneys, streets, bridges, squares, and clock towers. Everything drew to the eye at once.” Hugo leads the reader over a thirty-page excursion, landmark by landmark, neighborhood by neighborhood, building up a virtuosically detailed portrait of a city that is at once sweeping and minute. His description reads like the verbal version of a CGI-enhanced film scene, in which objects moving deep in the background maintain their HD clarity.

Real life presents a trade-off between distance and detail. You can spot an upper-story window a few blocks away and gauge its height and distance accurately. Pick a point on the horizon, though, and you have no way of knowing whether it’s one, five, or twenty miles away. Your sense of depth disappears. There’s nothing quite like comparing a cartographic city view with an actual map to make it clear that both of them lie a little. From where I watch, the Empire State Building stands hip-to-hip with 432 Park, though they are in fact more than twenty blocks apart. But the view also tells me what a map neglects to mention: that you could swing by zip line between the Woolworth Tower, near City Hall, and Frank Gehry’s 8 Spruce Street without hitting anything; that the spaces between buildings are cushioned in foliage; that the natural beauty of New York’s waterways endures.

The urge to see everything at once has often intruded into art. Sometime around 1600, El Greco followed a mule track into the hills around the Spanish city of Toledo, watching the way its buildings spilled down the ravines. No one perspective corresponded to his ideal of his adopted city, its ecstatic steepness and religious intensity. And so, for his famous View of Toledo, he whipped up a divine lightning storm, switched the location of the Alcázar and the cathedral to heighten the drama of the composition, and invented a compound across the river as a monastic retreat for the city’s patron saint. The World Trade Center pursues a slightly different kind of viewpoint multiplication, using technology instead of fiction. Visitors can stand on a circular “window” in the floor and look past their feet to the traffic on West Street a thousand feet below—except that they’re really standing on a solid concrete floor and what they’re seeing is a live camera feed projected onto a screen. Another $15 will get you the use of an iPad mapped with forty landmarks: touch one, and the camera swoops low over the city, zooming in on, say, Zabar’s or Yankee Stadium, with a ten-second description by the novelist Jay McInerney. Like Hugo and El Greco, Legends’ view-management system rejiggers distance for the sake of drama and clarity.

The potion of technology, ambition, viewlust, and economics that brought us to this point keeps getting more and more potent. So the question presents itself: How high will it lift the skyline? By global standards, and by the standards of all that’s possible, New York’s hugest buildings aren’t really that big. From the Empire State Building in 1931, at 1,250 feet tall, until Taipei 101 in 2004, the roof of the world rose just four hundred feet. Then, in 2010, it jumped another thousand feet, to the half-mile-high Burj Khalifa, a godlike spike in the desert. Its usurper is already under construction: The Kingdom Tower in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, will hit the one-kilometer mark (or 3,280 feet) when it’s completed, theoretically in 2018. The pace of supertall construction has accelerated recently, and if there is some theoretical or practical ceiling beyond which nobody will ever build, engineers haven’t found it yet. “I don’t see a limit other than people’s chutzpah—arrogance, actually,” says Ken Lewis, a principal at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill who managed the design of One World Trade. Arrogance is useful: A sizable segment of the architectural, engineering, and construction professions depend on it for inspiration and employment.

The mile-high skyscraper makes a little more sense to build than it did sixty years ago, when Frank Lloyd Wright imagined such a thing as a habitable sundial in the middle of Chicago called the Illinois. That idea couldn’t be realized at the time, and it remains hypothetical. A mile-high skyscraper would still be financially ruinous, slow to construct, and inefficient to operate, but that doesn’t mean it will never be built.

“Going big has been a trend ever since the pyramids. It has little to do with practicalities,” says Jay Siegel, an executive and engineer with Allianz, the company that might one day insure this Hubris Tower. The technology of supertall buildings is a bit like genetic testing or nuclear energy: a volatile form of power. Technological capacities have outpaced our judgment. We know we can do it, but we don’t know when not to do it. And so some preposterously wealthy mogul, most likely in South Asia or a Gulf emirate, will eventually move into a penthouse so far above the earth’s crust that the air is thin, gales hammer at the glass, and the elevator ride to the top is inadvisable if you have a sinus infection. A mile’s not science fiction. It’s not even an outer limit.

From a mile up, the world looks the way it does from an airplane, at the point during takeoff and landing when you can pick out an individual car beetling along a highway. In the not-unimaginably-distant future, this will be the view from someone’s breakfast nook. I asked William Baker, the SOM structure guru who figured out how to make the Burj Khalifa stand up, how he would respond if a developer with limitless resources came to him and said: “Okay, time to quit screwing around with ten stories here and a hundred feet there. Let’s build the mile-high tower.”

“Yup,” he answered. “Okay.” (Baker is originally from Missouri, and he is frugal with words.)

“How about a mile and a quarter?” I pressed.

“Yeah, we’d figure it out.”

“And at what point do you stop being able to figure it out?”

“I’m not sure. A mile would be twice the Burj. For now, let’s double what we have. Then we can figure out how to double it again.”

It’s easy to wave away architects’ impractical fancies: Wright’s mile-high Illinois, which in his drawings looks like the Burj Khalifa’s grandfather; also X-Seed 4000, a two-and-a-half-mile-high takeoff of the Eiffel Tower, and TRY 2004, a vertical city in the shape of a pyramid, both of which were designed to rear above Tokyo. But there is something irresistible about that phlegmatic bravado, the Midwestern matter-of-factness with which an experienced structural engineer like Baker suggests a whole new era of loftiness. For Baker, the mega-tall tower is really a new species, not just an inflated version of the skyscrapers of yore. He cites the biologist D’Arcy Thompson, who, in his 1915 classic, On Growth and Form, described with mathematical elegance the relationships between shape and size in nature. Different orders of magnitude require different skeletal structures. You can’t just inflate the Empire State Building and get its mile-high successor, any more than you can multiply a mouse to produce an elephant. Double the height and width of a blocky tower and you wind up with a dark-bellied leviathan, in which many occupants labor so far from windows that they might as well be stocking shelves in an Amazon warehouse. Instead, engineers have had to invent new structures, the kind that narrow from a sprawling mall below to a cozy penthouse palace.

That tapering comes at a cost. Each additional floor on top requires expensive extra concrete and steel down below, but it also gives back little. “When you look at the square footage gained by going up higher, at some point you could just build another building next door. There is a height where it no longer becomes economically feasible,” says Siegel, the Allianz executive. For a century, the rise of skyscrapers was propelled by an inexorable formula: the higher the cost of land, the higher the number of stories needed to pay for it. At a certain point—where, exactly, is a moving target—this logic falls apart. Instead, another craving takes over: the need for immensity.

Building at high elevations may seem like a rational enterprise, but it’s more like an extreme sport, filled with potential dangers. Piping junctions can snap, high-pressure hoses burst, cranes collapse, fires rage beyond reach. Wet concrete can start to harden on its way up to its destination. Even a minute shift in the earth below the foundations can knock a building askew.

In the first phase of skyscraper development, the greatest limiter of height was gravity. But as towers poked farther and farther into the sky, engineers had to deal with the more erratic forces of earthquakes and weather. A light breeze on the fourth floor can magnify into a gale on the 104th, and even infinitesimal vibrations can make people feel ill. Wind slams into a tower from one side, then splits into two arms. When the two streams whip around the building toward each other, they create vortices that spin off in a regular rhythm (a phenomenon called “vortex shedding”). Under the right conditions, the building will start snapping back and forth or humming like a guy wire, the vibrations increasing to intolerable levels. One common way to counteract that phenomenon is with a tuned mass damper, an immense ball suspended in the upper stories. A popular YouTube video shows how, during the massive Sichuan earthquake of 2008, an eight-hundred-ton ball of steel at the top of Taipei 101 swayed in its harness like an infant in a baby bouncer. When the top pitched left, the ball swung right, keeping the tower from moving much at all. (432 Park Avenue incorporates a similar system.)

Wind can also sculpt a high-tech tower the way it does a Bryce Canyon hoodoo. After placing a scale model in a sophisticated wind tunnel, architects try to disperse the onslaught by varying the obstacles at different heights, carving out channels right through the tower, adding fins, and softening curves. If supertall towers have gotten less symmetrical and more textured, that’s not all for show: It’s also a way of “confusing the wind,” a poetic phrase for creating calculated chaos.

The multiplicity of forces waging war on high-altitude architecture means that supertall buildings are necessarily designed from the guts outward. For decades, the tallest buildings have been collections of separate structures, fused in ever-more-complex ways. Chicago’s Willis (née Sears) Tower consists of nine square tubes bundled together like fasces. More recent colossi make use of the core-and-outrigger system, in which an immense steel truss links a powerful concrete trunk to thick columns at the edges. For the Burj Khalifa, Baker worked with the ex-SOM architect Adrian Smith (one of the designers of the Nordstrom Tower) to develop a buttressed core, in which three companion buildings, each with its own corridor, share a central spine, rather like three lanky drunks leaning on a lamppost. A mile-high skyscraper would most likely be a cheerleading squad of three or four towers standing hip to hip, with a companion on their shoulders. Which system gets used for which tower depends not just on its height but on how much land is available at the base, how close the nearest seismic fault line is, and the proportion of spaces for work and play.

Persuading a megastructure to remain vertical is only step one; the next job is getting thousands—even tens of thousands—of people in and out of it every day without each of them having to budget elevator time. Traditional steel cables are strong but so thick and heavy that a coil longer than about 1,500 feet becomes unmanageable. That simple physical fact dictates that to get up to, say, the 120th floor requires switching elevators—which means designing a sky lobby, fattening the core with additional shafts, and increasing the length of time it takes to get in and out of the building. Or that used to be true. A few years ago, the Finnish elevator company Kone inaugurated a lightweight carbon-fiber cable called UltraRope, which, at least in theory, could double the length of a single elevator ride to a full kilometer. If it lives up to its billing, that could make high-rises thinner, lighter, and far more energy-efficient—so that if you lived in a penthouse two miles high, you’d have to change elevators only twice. At this point, the limiting factor is not the technology of vertical transportation but the human body. A fast elevator can glide smoothly and silently into the skies, but if you’re riding it with a head cold, it will be murder on the sinuses. Nothing a Finnish engineer can do about that, except possibly pressurize the cab, though for now that remains a futuristic form of comfort.

Seen from New York, the notion of a mile-high tower can seem like a distant, screwball real estate venture, like an indoor ski slope in the desert or a fake Manhattan in China. “If we can build plenty of fifty- and sixty-story buildings, do we need any 120-story buildings?” asks the architect Jamie von Klemperer, who has an interest in the answer, since his firm, Kohn Pedersen Fox, is designing the sixty-five-story, 1,500-foot One Vanderbilt, going up next to Grand Central Terminal.

But just because there are no current plans to push a building’s height from profitable to narcissistic doesn’t mean it won’t happen. Manhattan is where global egos—and foreign money—come to roost, and there’s no telling what monuments they will choose to erect. Even a single Manhattan block could accommodate a 2,500-foot tower. A super-block (like, say, where the much-loathed Madison Square Garden now sits) could support something much bigger than that.

Even if the next generation of super-skyscrapers is built in other parts of the planet, it will still affect New York just by virtue of its existence. The world’s tallest towers are outliers by definition, but extreme height has a normalizing effect on slightly less extreme height. A few thousand-foot towers have already made their eight-hundred-foot sidekicks commonplace. Two or three contestants for the mile-high mark will sow an underbrush of half-milers. New York may never again boast the world’s highest anything, but the mere existence of thin-air buildings halfway around the world will surely pull the local skyline upward, too.