New York didn’t invent the apartment. Shopkeepers in ancient Rome lived above the store, Chinese clans crowded into multi-story circular tulou, and sixteenth-century Yemenites inhabited (and their descendants still inhabit) the mud-brick skyscrapers of Shibam. But New York reinvented the apartment many times over, transforming airborne slices of real estate into symbols of exquisite urbanity. Sure, we still have our brownstones and single-family homes. But in the popular imagination, today’s New Yorker occupies a glassed-in aerie, a shared walk-up, a rambling prewar with thick walls thickened further by layers of paint, or a pristine white loft.

The story of the New York apartment is a tale of need elevated into virtue. Over and over, the desire for better, cheaper housing has become the engine of urban destiny. When the city was running out of land, developers built up. When we couldn’t climb any more stairs, inventors refined the elevator. When we needed even more room, planners raised herds of towers. And when tall buildings obscured our views, engineers took us higher still.

This architectural evolution has roughly tracked the city’s financial fortunes and economic priorities. The early-twentieth-century Park Avenue duplex represented the triumph of the plutocrat; massive postwar projects like Stuyvesant Town embodied the national mid-century drive to consolidate the middle class; and the thin-air penthouses of Fifty-seventh Street capture the resurgence of buccaneering capitalism. You can almost chart income inequality over the years by measuring the height of New York’s ceilings.

The baronial library of William Randolph Hearst on Riverside Drive at West Eighty-sixth Street, 1929

The apartment was not always the basic unit of Manhattan life. To the refined nineteenth-century New Yorker, the idea of being confined to a single floor, with strangers stomping above and lurking below, was an intolerable horror, fit for greenhorns and laborers. Living adequately meant living in a house, even if it stood shoulder to shoulder with other identical houses, each one propping up its weak-walled neighbor. The most vivid way to conjure up what it meant to be comfortable in those pre-comfort days is to visit the Merchant’s House Museum on East Fourth Street, where Gertrude Seabury Tredwell was born in 1840 and died ninety-three years later.

After that, it was opened to the public. We tend to think of apartment buildings as vertical and houses as low to the ground, but the young Irish maids who tramped up and down the Seabury Tredwells’ mahogany staircases dozens of times a day would probably have disagreed. The Merchant’s House management has helpfully placed a bucket of coal in the basement kitchen so that visitors can feel its heft and imagine what it was like to schlep the thing up to the fourth-floor stove.

The front parlor at the Merchant’s House Museum

The house was not just a dwelling; it also functioned as hospital, maternity ward, funeral parlor, social club, workplace, dance hall, theater, auditorium, and school. It incubated elaborate social rituals that participants loathed but clung to fervently. The formal dinner party, for instance, depended on the existence of a formal dining room, a parlor to retire to afterward, servants with back-of-the-house access to the public rooms, and a kitchen just far enough away that it wouldn’t pollute the guests with its odors—all so that hosts and guests might join together in festive somnolence and mutter about nothing over processionals of mediocre food. “Is there anything in this world more wearisome, more dismal, more intolerable, more reckless, more sumptuous, more unbearable, anything more calculated to kill both soul and body, than a big dinner in New York?” demanded the Swedish writer Fredrika Bremer in the 1850s. Much further along on the tedium scale, however, was the ladies’ round of visits, another ritual that depended for its minutiae on the architecture of the private urban house. Women trotted around the city on the appointed afternoons, presenting visiting cards at one another’s residences and making deadly conversation that avoided impermissible topics—which is to say, almost all of them. Sometimes they didn’t come to talk at all but just left their cards, annotated with the nineteenth-century version of generic text messages, French phrases compressed into a terse code: p.c. meant “condolences,” p.p.c. was “good-bye” (pour prendre congé).

The Merchant’s House Museum evokes a stiff-collared time when the domestic architecture of the well-to-do functioned as both shelter and prison, especially for women. Even circa 1900, Edith Wharton’s socially sensitive anti-heroine Lily Bart in The House of Mirth has strong opinions about what sort of female belongs in a flat instead of a proper house: not the good kind. Invited into the apartment of her male friend Selden, she reacts to his exotic habitat with a mixture of distaste and almost erotic envy:

A breeze had sprung up, swaying inward the muslin curtains, and bringing a fresh scent of mignonette and petunias from the flower-box on the balcony.

Lily sank with a sigh into one of the shabby leather chairs.

“How delicious to have a place like this all to one’s self! What a miserable thing it is to be a woman.” She leaned back in a luxury of discontent.

Selden was rummaging in a cupboard for the cake.

“Even women,” he said, “have been known to enjoy the privileges of a flat.”

“Oh, governesses—or widows. But not girls—not poor, miserable, marriageable girls!”

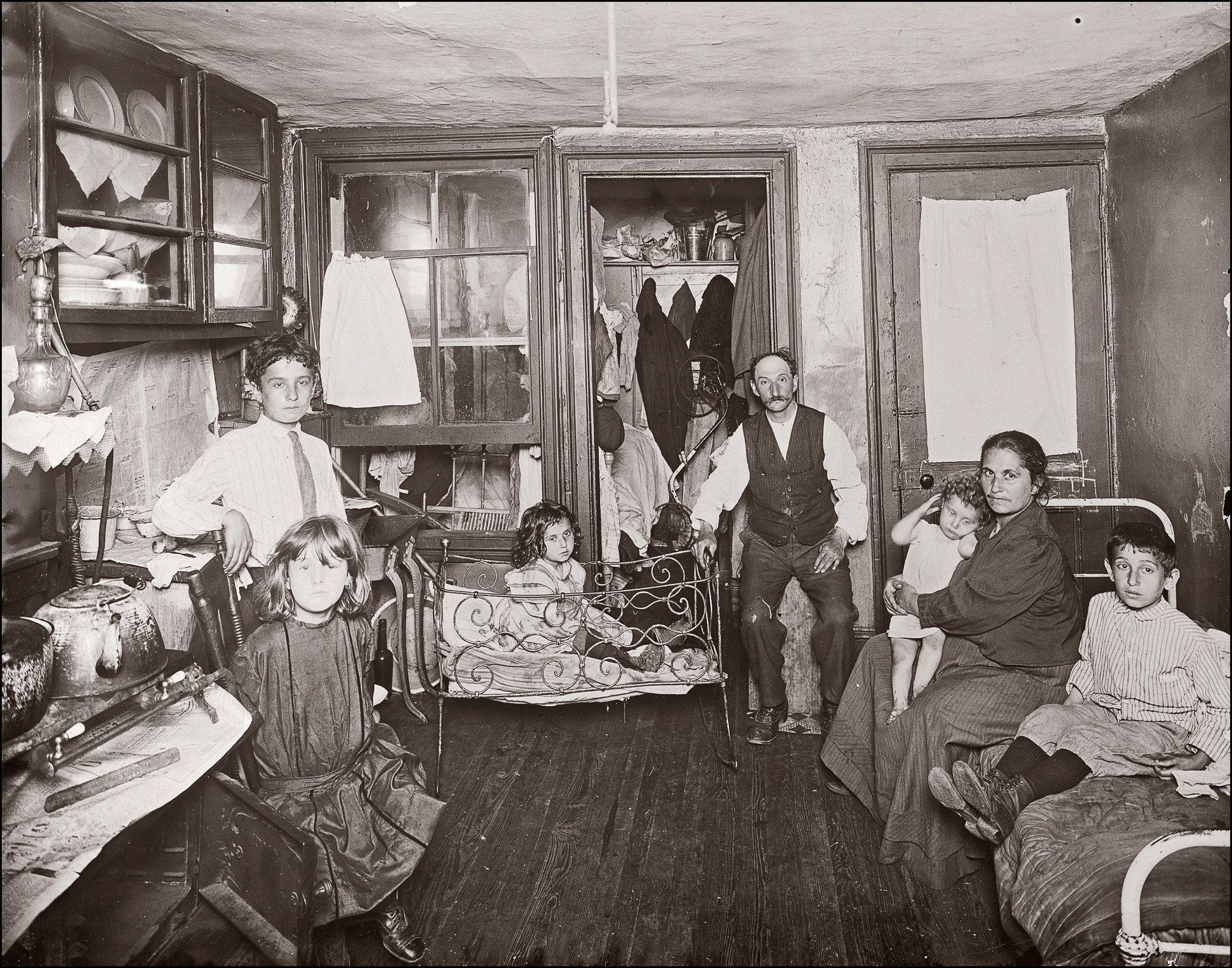

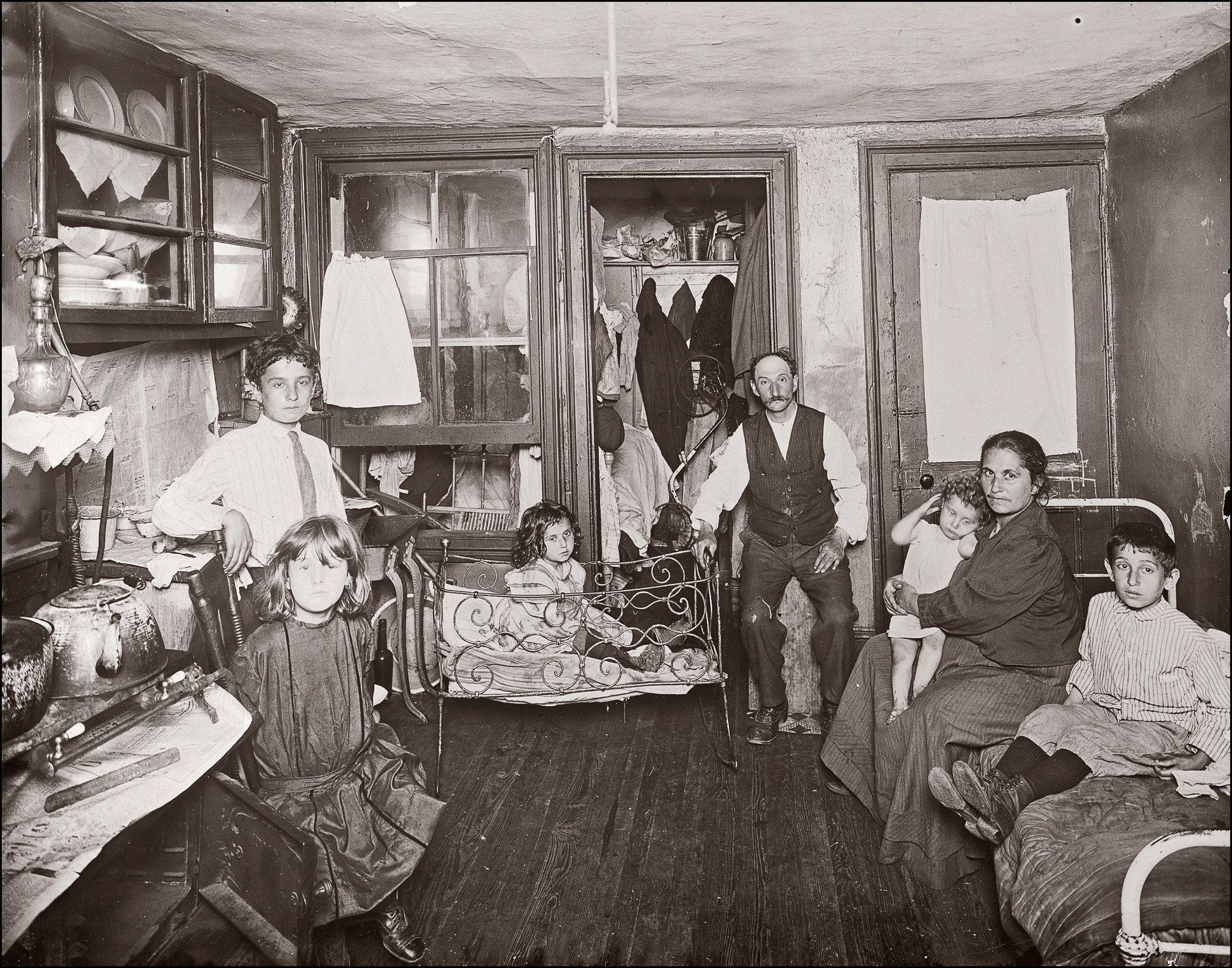

For the likes of Lily, the apartment had only recently distinguished itself from the tenement, that dank and rickety brick structure that existed to pack the poor together as cheaply and efficiently as possible. My ancestors lived in them, and yours may have, too: The urban tenement rivals the prairie log cabin and the Southern tarpaper shack as this country’s ur-dwelling, the humble place where our American story began. The Lower East Side Tenement Museum at 103 Orchard Street helps visitors envision what it was like to live in one: the half tub in the kitchen, the beds that slept children by the half dozen. Being a museum, though, it is also inauthentically clean and quiet and climate-controlled. What’s missing is the smell of cooking cabbage pluming up the stairs, the furious family fights ricocheting through the narrow air shaft, the crowded rooms choked with coal smoke in winter and thick with heat in summer, the windows open to the marketplace ruckus and the stench of horse manure, the relentless crush of human bodies.

The middle class feared that sort of proximity, and for them apartments, tenements, and boardinghouses were essentially interchangeable concepts. Especially after the activist photographer Jacob Riis brought extreme poverty to public attention in 1890 with the publication of How the Other Half Lives, a squalor safari was a popular adventure for journalists and reformers.

The bourgeoisie had plenty of opportunity to learn the colorful details of living in disease-ridden firetraps. Some were moved to help; most were simply glad of their own good fortune and terrified that it might slip away. Respectability was a crucial issue in a society as fluid as New York’s, where those who had achieved preeminence kept it only by erecting rigid social distinctions. In The House of Mirth, Wharton charts Lily’s decline by plotting her narrowing real estate choices: She moves from a relative’s house to a spare, lonely apartment, and then, after a brief stint as a social climber’s paid companion in a decadently luxurious hotel, she drifts even further downward to a shared one-room flat. She finally winds up in a boardinghouse, one step from the gutter.

Family room in a tenement

It took decades to cajole respectable New Yorkers out of their single-family homes, despite the arrival of a life-changing technology: the passenger elevator. Elisha Otis gave his famous demonstration of his patented safety catch at New York’s Crystal Palace in 1854, but the previous year Harper’s New Monthly Magazine was already making fun of it. The magazine foresaw that residential life would be changed, not necessarily for the better, by “the introduction of a steam elevator, by which an indolent, or fatigued, or aristocratic person may deposit himself in a species of dumb waiter at the hall-door, and by whistle, or the jingling of a bell, be borne up, like so much roast-goose with gravy, to the third, fourth, or fifth floor.” The article goes on to imagine the indignity of getting stuck in such an infernal gizmo.

“A 100 percent cooperative apartment,” 1924

In 1857, Calvert Vaux, who later became Frederick Law Olmsted’s partner in the design of Central Park, proposed a four-story, wide-windowed, thoughtfully designed set of “Parisian Buildings.” His drawing included an elegantly dressed couple entering the lobby, but that was wishful thinking. While the city’s population surged after the Civil War, and newcomers jammed into tenements, the affluent clung to increasingly exorbitant houses, even as they could hardly afford to build more of them. “Nothing denotes more greatly a nation’s advancement in civilization than the ornate and improved style of its architecture and the erection of private palatial residences,” the Times noted wistfully in 1869. With real estate values spinning out of control, the editorial concluded that the only realistic way to beautify the city was to erect more mansions for sharing: “the house built on the French apartment plan.” If such a dubiously Continental innovation could be made to seem palatable, even splendid, to the upper crust, the bourgeoisie would surely follow.

The first building to overcome these sensitivities was Richard Morris Hunt’s Stuyvesant Apartments at 142 East Eighteenth Street, a luxurious behemoth by 1870 standards. This structure defeated doubters with a two-pronged argument of aesthetics and pragmatism. The architecture oozed dignity: Five stories high and four lots wide, it had an imposing mass, an overweening mansard roof with yawning dormers, wrought-iron balconies, and ornamental columns. Even more persuasive, compared with the cost of building, furnishing, cleaning, and repairing a private home, all this respectability came as a bargain. Within a few years, the Times announced that a “domiciliary revolution” had taken place: A happy epidemic of flats had beaten back a plague of sinister boardinghouses. Young couples could now afford a bright new place in town; families no longer needed to fan out to the villages that lay miles from Union Square. The change represented the triumph of pragmatism over prejudice. “Anglo Saxons,” the Times reported in 1878, “are instinctively opposed to living under the same roof with other people, and it is doubtful if [that resistance] would have been overcome had not the earliest flats been of an elegant kind, in the best quarters of the town, and therefore, expensive and fashionable.” The rich made the apartment safe for the middle class.

Yet the first generation of buildings merely replaced old anxieties with new ones. Total aversion to apartment living gave way to practical puzzlements. Genteel New Yorkers saw the new architecture as an assault on moral rectitude. Visiting a lady in her Washington Square townhouse was a public, social act: You parked your carriage on the street and knocked on the big front door. But an apartment dweller could sneak downstairs to nuzzle a neighbor’s spouse without anyone having to know. Apartments also couldn’t always reproduce the strict segregation between sleeping quarters and public rooms, or between residents and servants. In the earliest, Paris-style layouts, a master bedroom connected to the parlor by a French door, but Americans were unsettled by the notion of allowing visitors a glimpse of a bed.

For people afraid that the new architecture would chip away at propriety, the list of worries was long and obsessive: that neighbors would have to make physical contact when passing each other in a shared hallway (a greater concern in an age of ample crinolines); that cooking smells could not be confined; that employers might inadvertently lay eyes on their servants—or, worse, on someone else’s; that children would not be properly policed. Not all these embarrassments have gone away (one of my neighbors opens her front door whenever she’s been frying fish, to clear the smell from her apartment), but developers faced them squarely. Builders adopted an assortment of strategies to dispel qualms about apartments’ suitability. In 1884, the Chelsea opened on West Twenty-third Street as one of the city’s first luxury co-ops, sparing residents the indignity of living in hired quarters. (Having evolved from an owner-occupied enclave of the well-to-do into the storied and famously shabby Hotel Chelsea, it has now gone condo.) That same year, the Dakota, on West Seventy-second Street, offered crowd-shy burghers access to Central Park just outside their gate and, inside, a quiet courtyard enclosed by a mock château replete with peaked gables, bays, and wrought-iron railings. These lavish touches effectively collectivized social status: Whereas the one-family mansion declared its owner’s separate prominence, the Dakota’s bulk and ornamental façade signaled that everyone who lived there was, by definition, Our Sort.

Wealthy, powerful people attract plenty of unwanted attention, and the Dakota’s extremes of neo-Gothic sumptuousness have made it the setting for a whole festival’s worth of real and fictional dramas over the years. John Lennon moved in in 1973 and in 1980 was murdered on the sidewalk out front. Mia Farrow drifted down its spooky hallways in the 1968 movie Rosemary’s Baby, which treated it like a haunted castle dropped into the middle of Manhattan. Leonard Bernstein, Judy Garland, Lauren Bacall, and Rudolf Nureyev all lived there, giving the building the air of a celebrity clubhouse.

In 2011, Alphonse “Buddy” Fletcher, a black Harvard graduate, hedge-fund manager, philanthropist, and two-time board president of the Dakota, tried to buy an apartment in the building for his mother to live in (he already owned multiple Dakota residences). The co-op board refused, and Fletcher sued, describing the building in court papers as a bastion of old-fashioned racism. The whole thing might have remained an internecine dispute, except that Fletcher’s lawsuit rebounded on him, focusing attention on his finances, which suddenly appeared to be tottering. Adding to the tabloid fodder was the fact that, after a long relationship with a gay man, Fletcher had switched allegiances and married Ellen Pao, another Ivy League overachiever—who filed (and lost) a discrimination suit against the Silicon Valley venture-capital firm where she worked. This litigious whirl of sexuality and race, respectability and disgrace, sudden sums and extravagant real estate made the story irresistible. Vanity Fair published a long feature article about the affair and headlined it SEX, LIES, AND LAWSUITS. The Dakota’s unified front of snobbery cracked, revealing a small town’s worth of squabbles, resentments, and payback, only with more zeroes.

What eventually assured the success of apartment living was the same fundamental element that has always shaped New York: money. The building’s most persuasive asset was that it allowed the affluent to live better than ever while still downsizing the household staff. There were savings in numbers: In a large building, the cost of steam heat, electricity, and elevators could be shared. Instead of each family employing a laundress, one or two building employees manned huge machines in the basement. Residents of the finer addresses took their meals in vast and elegant central dining rooms, like passengers on a perpetual cruise. Those who preferred to eat at home but lacked a cook could have boxed meals prepared by the building staff and sent up by dumbwaiter. (New Yorkers have always been addicted to takeout.)

By the turn of the century, the mansion had become an albatross, not just expensive but primitive compared with a giant technological wonderland like the Ansonia Hotel at Broadway and Seventy-fourth Street, which opened in 1904. This was the bourgeois pleasure dome of early-twentieth-century New York. The young single man who installed himself in one of the 1,400 rooms and 340 suites could choose whether to move in his own bed and chest or select from the hotel’s catalog of paintings, furniture, carpets, and hand towels. He could scrutinize the other transient and permanent guests by the dazzle of electric lights, dine in a restaurant that served five hundred, take a postprandial stroll past the live seals cavorting in the lobby fountain, and ride the quiet, exposed elevators just for the pleasure of seeing the seventeen stories scroll by. A few blocks over, the Hotel des Artistes on Central Park West at Sixty-seventh Street opened in 1917 as live-work space for gentleman artists, who required a northern exposure and high ceilings, even though some residents never touched a palette.

Aaron Naumburg, a rabbi’s son from Pittsburgh and a fur magnate, lived in the grandest of the double-height dwellings. There, Persian rugs hung from the carved wood balcony that looked out over a vast living room encased in seventeenth-century English panels. The place resembled a period room and eventually became one: After Naumburg and his wife died, the interiors were disassembled and brought to the Fogg Museum at Harvard.

The immigrant architect Emery Roth erected the apotheosis of early-twentieth-century domestic grandeur on Central Park West at Eighty-first Street: the Beresford, a fairy-tale confection of towers, wrought-iron grillwork, terra-cotta cherubs, pediments, and balustrades. Each apartment pinwheeled around an entrance foyer, so that the sleeping quarters, public rooms, and servants’ wing could be simultaneously separate and close at hand. Only New York could produce a monument to Jewish home life as imposing as the Beresford, and perhaps only in the late 1920s, in the exultant moment before the stock-market crash.

The Depression slammed the portcullis down on the era of residential magnificence. The Ansonia was chopped up into cubbies. The Beresford was sold off for a pittance. The Majestic, on Seventy-second Street, and the San Remo, planned in flush times, were completed in miserable ones and faced immediate financial trouble. Hundreds of other Upper West Side buildings, more modest but still genteel, adapted to less easeful times. Maids’ rooms were repurposed as bedrooms. Bell boxes for summoning servants were disconnected. Stained-glass windows broke and were replaced with ordinary panes.

Savage as it was, the Depression thinned but did not extinguish the ranks of the wealthy, and some sumptuousness did slip through the closing gates. In 1931, the River House materialized on East Fifty-second Street, and its twenty-seven-story tower, flanked by fifteen-story wings, rose over the East River like an ocean liner. Inserted into a neighborhood of slums and slaughterhouses, River House retreated behind its gated court, a citadel reaching far above the gloom. The luckiest residents never needed to dirty a shoe on the cobblestones: They could, if they wished, commute by boat to Lower Manhattan or their Westchester estates from the private marina (an amenity later obliterated by the FDR Drive). I spent two college summers staying in a large River House apartment by myself, mystified that the absent owners—or anyone, really—could feel at ease in so much space. I had no use, of course, for the immense formal dining room with the foot-activated buzzer beneath the vast mahogany table to signal that the cook should bring the next course. The narrow balcony that once protruded over the private marina now hung above the thunderous FDR Drive, giving dinner al fresco the feel of a picnic on a highway median. I avoided the long Shining-like hallways and instead snuck from my bedroom through a back landing to the kitchen like a furtive maid, letting the rest of the apartment stretch out in unmapped darkness. The place creeped me out, which is odd, really, because when the building opened it represented the quintessence of open, spacious living.

Samuel Gottscho took photos from the higher floors and captured the thrill of living at those rarefied altitudes, when street level contained so much squalor. The haloed skyline, the chrome-plated water spreading out beyond the great bay windows, the airy apartments washed in morning light—all made River House the Valhalla of New York.

In that first phase in the saga of the New York apartment, the middle class emulated the prosperous in order to separate themselves from the poor. In the next chapter, plain but modern housing for the poor became the standard for everyone else. Widespread hardship, followed by a world war and a housing shortage, plus a multi-decade campaign to flatten differences in income, meant that New Yorkers of all strata were moving into streamlined homes, with lower ceilings and restrained rents.

Affordability and dignity had always been a goal of apartment advocates. In 1867, 1879, and 1901, progressives had pushed through laws requiring small increases in the standards of ventilation, light, and sanitation in tenements. In the 1870s, the Brooklyn philanthropist Alfred Tredway White built handsome complexes of worker houses like the Tower Buildings in Cobble Hill, which featured a toilet in each apartment, outdoor staircases, meticulous brickwork, and wrought-iron railings. But it was the Depression that brought the issue of how to house the have-nots into the realm of public policy. “Down with rotten, antiquated ratholes! Down with hovels! Down with disease! Down with crime!” proclaimed Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, ushering in a new bureaucracy charged with providing decent shelter: the New York City Housing Authority, known forevermore as NYCHA (pronounced NYE-tcha). In 1935, NYCHA rehabilitated a neighborhood of crumbling Lower East Side tenements by tearing down every third house, to maximize light and air, and renovating or rebuilding the rest. In the end, the First Houses project required near-total reconstruction, but the result inaugurated the public-housing era and remains an emblem of the promise, as La Guardia put it, “to give the people of my city, in place of their tenements, decent, modern cheerful housing, with a window in every room and a bit of sunshine in every window.”

Providing apartments to those who needed them proved such a massive undertaking that all levels of government had to get involved. Rent control arrived in 1943, and a smorgasbord of federal, state, and city agencies floated bonds, granted tax breaks, wrote checks, evicted citizens, and redrew maps, all in an effort to eliminate putrid slums and erect stands of thick, solid towers instead. Private developers got in on the action, too. The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company opened Stuyvesant Town as a middle-class gated community around a series of verdant courts. One irony of that contradiction-laced period is that in order to save the decaying city, densely populated towers cut themselves off from the noise and mess of urban life. Residents didn’t necessarily demand distance from the street, but planners did. “The growing antimetropolitanism of most housing architects [was] matched by the new suburban bias of the bankers, lawyers, and bureaucrats who wrote the programs and administered the policies,” write Robert A. M. Stern, Gregory Gilmartin, and Thomas Mellins in New York 1930.

The story of mass housing is an intricate epic of idealism, destruction, and partial successes. Public projects obliterated neighborhoods, boosted the crime and segregation they hoped to alleviate, killed miles of street life, and vivisected vibrant communities—but they also redeemed a lot of grimly constricted lives. Look out over the Lower East Side from the Williamsburg Bridge, and instead of the chaotic ground cover of moldy tenements from a century ago, you see an orderly pattern of X-shaped high-rises, separated by greenery. From this altitude, you can almost recapture the mid-century optimism about public housing, the belief that erecting enough modern apartments could if not cure inequality at least mitigate its effects. In many cities, that experiment in social engineering has gone down in history as an abject, abusive failure. Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, Cabrini-Green in Chicago, Lafayette Courts in Baltimore—all over the country, mayors dynamited degraded brick towers in the belief that architecture had aggravated problems it was meant to address. New York has by far the nation’s largest public-housing program, with an unofficial population of six hundred thousand—almost exactly that of the city of Baltimore—and it has had a different experience. The towers have endured, frequently decrepit and ravaged by drugs and crime but filled with people who are fiercely protective of their status as NYCHA residents. These high-rises were usually located in the least desirable parts of the city; now some find themselves encircled by creeping luxury. Once, the nearest supermarket was a grim hike away. Now there’s an organic-food store across the street, but the beautiful produce is still out of reach. A moat of bitterness encircles some of these projects: Residents feel abandoned, isolated, and threatened, while neighbors feel that the towers mar otherwise-golden enclaves of privilege. But anyone who looks on these hulks and wishes them away might remember the words of an early resident, a garment worker who said: “Before, I lived in the jungle. Now I live in New York.”

“I live in New York.” The pride buzzing through that phrase brought people here in search of whatever damp, dim, cramped digs they could find. Even as the authorities were condemning acres of cold-water walk-ups in East Harlem and the Lower East Side, Abstract Expressionist painters were renting similar apartments in Greenwich Village. If for Wharton’s Lily Bart a poky flat represented the last rung before indigence and an early death, for the siblings in Ruth McKenney’s 1940 play My Sister Eileen (and its 1953 spinoff, Wonderful Town), a basement pad in the Village had a raffish, stage-worthy glamour. “It is a large room and far from cheerful, but there is an air of dank good nature about it that may grow on you,” read the stage directions for the opening scene. Like the garret in La Bohème, it’s the sort of place that makes penury cool.

So powerful was the ideal of the apartment for the masses that luxury buildings aspired to it, too. Postwar architects embraced the austerities of modernism, which they applied to bourgeois quarters as rigorously as they did to public housing. The most bracing high-end apartment building was Manhattan House, an immense 1951 complex; architect Gordon Bunshaft clad it in glazed brick that everyone called white but was actually pale gray and has always looked slightly unwashed. Stretching along East Sixty-sixth Street between Second and Third Avenues, Manhattan House adapted the grand apartment to the stripped-down modern era persuasively enough to attract Grace Kelly as a resident, and Bunshaft chose to live there, too. Its huge scale, stark design, and chain of slabs sitting back from the sidewalk evoked Stuyvesant Town more than the prewar palazzi like the Beresford. Half a century earlier, New Yorkers had hoped to live fabulously. Now it was stylish to live just well enough.

It soon became difficult to distinguish Manhattan House from the knockoffs that developers churned out for less discerning clientele. For a while in the fifties and sixties, it seemed as though every new residential building, whether it contained compact studios or assembly-line “luxury” pods, wore a uniform of glossy white brick. An aesthetic of conspicuous sameness, developed for the poor and taken up by the affluent, trickled back to the middle class.

The charms of standardization eventually wore thin, and the New York apartment soon experienced a transformation almost as fundamental as it had at the turn of the century. In the sixties and seventies, many of the industries that had fueled the city’s growth a century earlier failed, leaving acres of fallow real estate south of Houston Street. At first, nobody was permitted to live in those abandoned factories, but the rents were low and the spaces vast, and artists were no more deterred by legal niceties than they were by rodents and flaking paint. They arrived with their drafting tables and movie cameras and gloried in the absence of fussy neighbors. They would demarcate a bedroom by hanging an old sheet, or turn one end of the long space into an impromptu stage, with the audience sprawled on the paint-speckled floor.

The music critic John Rockwell later recalled the casually ecstatic atmosphere that surrounded the loft concerts of Philip Glass in the early seventies, before he began churning out operas and soundtracks for pretentious movies. “The music danced and pulsed with a special life,” Rockwell wrote of a 1973 performance of Music with Changing Parts, “its motoric rhythms, burbling, highly amplified figurations and mournful sustained notes booming out through the huge black windows and filling up the bleak industrial neighborhood. It was so loud that the dancers Douglas Dunn and Sara Rudner, who were strolling down Wooster Street, sat on a stoop and enjoyed the concert together from afar. A pack of teenagers kept up an ecstatic dance of their own. And across the street, silhouetted high up in a window, a lone saxophone player improvised in silent accompaniment like some faded postcard of fifties’ Greenwich Village Bohemia. It was a good night to be in New York City.”

At a time when urban populations everywhere were dispersing to the suburbs, this artists’ colonization had a profound and invigorating effect not just on SoHo but on the entire city. The traditional remedy for decay was demolition, but artists demanded the right to stay. Their presence attracted art galleries, and a treasury of cast-iron buildings acquired a new purpose. Artists didn’t think of themselves as creating real estate value, but they did. Few events illustrate the maxim “Be careful what you wish for” better than the Loft Law of 1982, which forced owners to make SoHo’s industrial buildings fully habitable without charging the tenants for improvements.

It was a triumph and a defeat. Legal clarity brought another wave of tenants, with more money and higher standards of comfort. As working artists drifted on to cheaper pastures in Long Island City, Williamsburg, and Bushwick—or out of the city altogether—SoHo’s post-pioneers renovated their lofts, hiring architects to reinterpret the neighborhood’s industrial rawness, or merge it with cool pop minimalism, or carve the ballroom-size spaces into simulacra of uptown apartments.

Once everyone wanted to be a tycoon; then everyone wanted to be middle class. Now everyone wanted to be an artist, or to live like one. SoHo filled up quickly, and the idea of the loft spread, reinterpreted as a marketable token of the unconventional life. The loft promised to lift the curse of the bourgeoisie through the powers of renovation. Realtors began pointing out partition walls that could easily be torn out. Lawyers, dentists, and academics eliminated hallways and dining rooms, folding them into unified, flowing spaces. Happily for those with mixed feelings about the counterculture, loft-like expansiveness overlapped with the open-plan aesthetic of new suburban houses. Whether in imitation of SoHo or Scarsdale, the apartment kitchen migrated from the servants’ area to the center of the household, shed its confining walls, and put on display its arsenal of appliances. Cooking became a social performance, one that in practice many apartment dwellers routinely skipped in favor of ordering in, going out, or defrosting a package—but at least the theater stood ready.

Starting in the eighties, when the country more or less abandoned the pursuit of greater equality, and fresh college graduates coaxed the financial system into dumping sudden millions in their laps, the apartment took yet another turn. Triumphant traders—“Masters of the Universe,” in Tom Wolfe’s phrase—didn’t spend much time at home, but in their few moments of leisure they wanted to gaze down on the city they had conquered.

For the next two decades, developers treated the apartment less as a private retreat than as a belvedere—a platform for a vista. For a time, the ultimate expressions of the panoramic apartment, which required vertiginous height, very fast elevators, and a perimeter of glass, were the penthouses atop Trump World Tower. This dark bronze totem that Costas Kondylis designed for Donald Trump at 845 United Nations Plaza (First Avenue between East Forty-Seventh and Forty-eighth Streets) was the planet’s tallest residential building (and the one most loathed by its neighbors) when it opened in 2001. It was not shy about its stature. The ceilings got higher near the top, so that the tower appeared to be craning its neck, and, with vintage Trumpian hyperbole, the seventy-two floors were deceptively numbered up to ninety. The payoff was an IMAX view of the skyline below and the weird sensation that the closest neighbors were gulls, planes, and clouds. Of course, that sort of solitude only lasts until the next neighbor climbs the mast. The push to refine the apartment began with assurances that a fifteenth-floor home could rival a house set on a fifteen-foot stoop; today, a one-hundred-fiftieth-floor penthouse is not unthinkable.

Bjarke Ingels’s VIA57

Vertical living has behaved as promised: It multiplied the value of limited land, streamlined the machinery of leisure, sheltered the masses, and concentrated entrepreneurial energy into a compact urban zone. But the price of height is lightweight construction: glass walls, thin floors, and plasterboard walls. The original barons of the Beresford would have found today’s condo towers pretty flimsy castles in the sky. New York has done such a thorough job of glamorizing the high-rise apartment that a Manhattan pied en l’air has become a billionaire’s accessory and an eternal object of desire. Developers have searched for ways to leverage that lust—to reconcile the assembly-line efficiencies of the construction business with the quest for ever-greater heights of pampering. Enter the preposterous amenity. Today, the most extreme buildings compete to provide a Gilded Age menu of extras. If you want your dog to get his treadmill workout while you practice climbing a rock wall, then snuggle up together by the rooftop fire pit, you can do all that without ever leaving home.

In theory, the ultra-high-rise should not be simply an instrument of extravagant living but a path back to the egalitarian policies of the mid-twentieth century. In his book Triumph of the City, the Harvard professor Edward Glaeser argues that New York’s vitality depends on people being able to live here and that the only way to make apartments affordable is to erect more of them. Mayor Bill de Blasio staked his mayoralty on just such a push, and the Department of Buildings authorized the construction of more than fifty thousand apartments in 2015—enough to house an entire new (small) city. But while builders keep cranking out the same few sizes and layouts, residents come in a dizzying and changing variety of configurations. Post-college roommates, groups of immigrants sleeping in shifts, multigenerational families, single-parent families, single business travelers who spend virtually no time at home, seniors who want to stay put but need less space than they once did, entrepreneurs who run businesses out of their homes—all their different needs challenge the construction industry’s craving for standardization. Architects have offered an elaborate menu of ideas to address a changing urban society, including gerbil-scaled apartments and dorm-style shares. Mostly what they boil down to is charging more money for less space.

In every growth spurt, rental towers pop up all over the city like architectural acne, a pox of large, unsightly blocks whose creators claim it’s the best they can do. But one architect who flicked away excuses to create something really fresh is the Danish superstar Bjarke Ingels, whom I met in 2011, when he was trying to explain what he had in mind for the desolate juncture of West Fifty-seventh Street and the West Side Highway.

His first New York building, he said, would fuse two apparently incompatible types: a European-style, low-rise apartment block encircling a courtyard, and a Manhattan tower-on-a-podium, yielding something that looked like neither and behaved like both. New York was ready to embrace such a griffin, he insisted: “This is the country that invented surf ’n’ turf! To put a lobster on a steak: Any French chef would tell you that’s a crime.”

Five years later, Ingels walked me around the finished work (now called VIA 57 West), a gracefully asymmetrical peak with a landscaped bower in its hollowed core. The façade does double duty as the roof, swooping up from the shoreline to the mountainous ridge of Midtown. It follows a hyperbolic paraboloid, the curving, mathematically precise surface that gives us the Pringle and the saddle roof. In the early sixties, swooshes and upturned canopies captured the era’s youthful eagerness, its faith in a limitless economy, in capitalism, technology, and the lure of space travel. Ingels taps into this Kennedy-era moment of futuristic self-confidence, not for its nostalgia value but to recover the geometry’s forgotten potential. The crosshatched lines formed by the thousands of steel sheets make visible the curving grid of a mathematical diagram. Each panel is unique, cut and bent by an infinitely patient computer and assembled by workers who had to figure out what they were doing along the way.

The result resembles an aircraft wing, a ski slope, or a wave. It’s tempting to see this as a celebrity architect’s theatrical flourish, but consider all that the shape achieves: It maximizes river views and covered balconies, protects even low apartments from the noise of the highway, pierces the skyline with a jaunty top, and leaves room for a courtyard that even in winter basks in sunlight most of the day. The building looks wild, but it’s born of logic; true originality flows from rigorous thinking. Ingels’s inventiveness suggests that maybe all the contradictory forces of New York’s real estate history can somehow be brought into equilibrium and the next generation of apartment buildings can combine affordability with vintage grandeur, great height, and the relentless pursuit of ease. That may seem like an implausible quartet of attributes, but it’s precisely what the first middle-class alternatives to the tenement and the boardinghouse offered 150 years ago.

My first New York apartment was a one-bedroom on West 120th Street near Morningside Drive that I shared with my girlfriend (now wife). A grim security gate over one window gave the bedroom a certain cellblock chic, and one wall of the living room doubled as kitchen. Daylight paid a brief morning visit, dispensing a small, glowing square on the floor that lasted about an hour. The rest of the place was so dim that our cat spent his days sunning himself under a desk lamp, resting up after his nocturnal cockroach hunt. I was a graduate student at Columbia, which had bought the dilapidated building and was patiently waiting out the motley collection of tenants whose leases were part of the deal. Next door lived an elderly, impeccably gracious Japanese woman whose sole self-indulgence was a pair of Ferragamo shoes. Down the hall was Al, a tall and skeletal crack addict who might have been around thirty, or possibly sixty-five, with a nonchalant attitude about garbage disposal; he frequently carpeted the stairwell with chicken bones. Al periodically dropped by to “make a local call” to his dealer. Eventually we started responding to his signature knock—three slow, deathly thumps—by holding our breath until we heard him shuffling away. From time to time, we heard gunfire crackling a few blocks away.

In search of less excitement and more square footage for the same rent, we moved to a comparatively palatial apartment in Sunnyside, Queens. There the kitchen could accommodate a breakfast table, and the cat could position himself on the second-floor windowsill and parley with the squirrels in the tree outside. Later, we lived in a Manhattan high-rise built in the eighties, recently enough that some in the neighborhood still think of it as a monstrous interloper.

Thinking back over that trajectory, I am struck that almost the entire history of the New York apartment remains on the menu today, albeit at preposterous prices. Each listing is a potential location for the drama of someone’s life. The crowds who troop around to open houses every Sunday are never just counting bathrooms and closets or calculating mortgage payments. They’re wondering whether a refurbished tenement speaks of hoary miseries or new excitement, whether the view out each window is one they want to see every day, or whether they can see in their prospective neighbors the people they want to become. To hunt for an apartment is to decide which New York you belong in.