GROWING UP AND LEARNING TO FLY

MY EARLY LIFE

I was born in Wrexham, North Wales in my grandmas house, 48 Bradley Road, on 13th October, 1915. I was the first son of Ernest George Rosier and his second wife Frances Elisabeth, née Morris. My fathers first wife Ruth, by whom he had two sons, had died in 1912 and he married Frances in December 1913. The elder of my two halfbrothers, Hugh, was pleasant and good-natured, he worked on a farm; the younger, Phillip, seemed to me to be a strange lad. I remember that each one came to visit us two or three times a year. Hugh died when I was aged sixteen; but by then Phillip had already disappeared out of our lives.

I was six months old when my father s job as an engineer on the Great Western Railway took us to Corwen, a small town twelve miles west of Wrexham on the River Dee. My father, who had briefly been a teacher, had many interests: gardening, playing the flute and keeping up to date with the development of wireless and the improvements in sound reproduction. He made the original ‘cats whiskers’ wireless with headphones, later graduating to the new sets using valves and loudspeakers.

But his main interest was in wood carving and cabinet-making which he taught at night school in Corwen. In the parish church there is a carved oak font cover made from an old oak pew presented by him as a memorial to those of the parish who died in the First World War. Other examples of his work, which include a carved oak sideboard, are in our cottage in Wales.

As for my mother, she was kind and good-natured, always putting our interests first. The relationship between her and my father was close and mostly harmonious; but I can recall occasions when she lost her temper with him. She was careful about spending money; he was a spendthrift, running up debts, mostly on buying technical magazines, carving tools and radio parts, which we could ill afford. Then came the fireworks!

During the eleven years we spent in Corwen we lived in a terrace house just above the town itself. At the back was Pen-y-Pigyn Mountain, with moorlands stretching out far beyond. There in summer we picked wineberries for jam making. From the front of the house we had an expansive view of the mountains beyond the valley of the River Dee, in which I learned to swim and fish.

At the age of five I went to the National School (C of E) and although I remember very little of my time there, the teaching must have been good. Age nine I passed the scholarship to the County School at Bala. The ruling by the Merioneth Education Committee that entrants to its county schools should be ten on 1st September worked against me and consequently, I had to wait for a further year until September 1926 when I was nearly eleven to start there.

I travelled daily by a Great Western Railway train on the twelve-mile journey to Bala. My friends and I would often spend our lunchtime at the side of Bala Lake, back then it was just a huge, empty expanse of water. Now it has been developed by the Welsh Tourist Board as a water sports centre.

Like my father, I enjoyed music. For a few months I took piano lessons but these were stopped because I did not practice enough. Next I tried the violin, which I found much more to my liking. I had a good teacher and practiced regularly, alongside joining the church choir.

During our time in Corwen my twin sisters, Marian and Rose, and my brother Bill were born.

In 1927, after only two terms at Bala, I had to leave and move to Wrexham County School, Grove Park, because my father’s job had taken us to Gwersyllt, a small village three miles from Wrexham. We lived in two houses in Gwersyllt, both railway tied, then in 1933 we moved into a newly built semi-detached house in Rhosddu, Wrexham which my father called Ramsbury Cottage after the village in Wiltshire where he was born.1

I was very happy in my new school, which had a fine reputation for academic and sporting achievements. Unfortunately, I did little work. The sciences, mathematics and geography were the only subjects in which I was interested. Not surprisingly in 1930, I failed to matriculate in the Central Welsh Board (CWB) School Certificate examination. As I could not pass English which was necessary for matriculation, I had to take it a second time in 1931 and then for a third time in 1932 before passing. In those days, without passing you could not advance to the sixth form. Having finally got there, and only concentrating on the subjects that interested me, two years later in 1934 I gained the Higher School Certificate of the CWB in mathematics, physics and chemistry.

Sports were my top priority during my time at school. I was in the rugger team for four years and was captain in my last year. I was in the tennis team for four years and captain for two. I was also captain of the swimming team and, for the record, a school prefect for three years and house captain for my final two years.

In 1934 I was selected as hooker for the North Wales schoolboys’ team against South Wales. The match, played at Ruabon School, was, not surprisingly, an overwhelming victory for the South Wales boys. At least two of their side became household names – Davies and Tanner were first choice as three-quarters for Wales for many years. Wilf Wooler from the North, after winning his Blue at Cambridge, was for many years captain of the Welsh team.

Whenever possible I played for Wrexham Rugby Club – a pleasant but inebriated bunch. Indeed, the first time I ever drank too much was after an away match for Wrexham 1st XV against Birkenhead Park.

Twice a week I cycled the three miles to St. Mark’s church in Wrexham for choir practice, and twice every Sunday for Matins and Evensong. For a year or two I was the treble soloist, and still remember the words of my favourite solo ‘Oh, for the Wings of a Dove ...’ My violin playing had progressed so well that I played in the school’s small orchestra and later in the Denbighshire Youth Orchestra.

The author playing Malvolio in a performance of Twelfth Night whilst at Wrexham County School, Grove Park, 1933.

I also enjoyed acting, taking a leading part in a number of school plays. On one occasion, when playing Malvolio in Twelfth Night with my usual fervour, I flung my chain of office across the stage with such vigour that it landed with a crash on the stage lights, fusing the lot. The resulting total darkness raised laughter and raucous cheers from the audience, composed mainly of fellow school mates. They approved, but the reaction of the master in charge was quite different. I was invited to join an amateur dramatic club. I well remember touring the local parish halls and miners’ institutes playing ‘The Tolpuddle Martyrs’ – this was thought to be very worthwhile by most of my fellow actors who were to a man socialists and trade union activists.

In my last years at school I became interested in a very active and attractive girl called Hettie Blackwell. She captained Grove Park Girls’ school hockey and tennis teams and later played hockey for Denbighshire. She came first in many field sports, winning the Senior Athletics Cup. At first I think I was impressed by the sight of her well shaped legs but clearly there was more to it than that. She must also have been good academically for she romped through to her Higher School Certificate in 1933. That September whilst I, poor chap, was still at school, she went to St Mary’s College, Bangor where she studied to become a school teacher. During that time I wrote to her every Friday.

In the winter of 1934, my mother was not well and in February, the terrible pain in the base of her spine she had been suffering with was diagnosed as cancer. She was admitted to the War Memorial Hospital in Wrexham, where she died a few months later. She was buried in Gwersyllt Parish churchyard where my father, who died in 1942 whilst I was in the Western Desert, was also laid to rest. This was one of the saddest moments of my life and it was only after my mother’s death that I realised what a dominant influence she had been.

16th February 1934

My Dearest Hettie,

I’m not going to write much tonight because I’m utterly fagged out – after being up till two o’clock every morning. Mother’s very ill – had to take her to hospital last Sunday. She’s practically paralysed from the waist downwards.

I’m taking the part of a German colonel in the house play for Eisteddfod. Thanks very much for that valentine card, and I’m awfully sorry I forgot your birthday.

Having gained my Higher School Certificate in l934 I had to think of the future. As we had little money, in order to go to university it was necessary that I gained a scholarship. My failure to be awarded one by both Manchester and Bangor caused me to look around for something else to do. As unemployment was extremely high in Wrexham and there were no jobs to be had other than in the mines, I decided to stay at school and play rugger while applying for jobs. That November I wrote to Het about a weekend trip to London I made with my father when I visited the Science Museum and saw a football match between Sheffield and the ‘Spurs’ ending the day at Her Majesty’s Theatre seeing a performance of C.B. Cochran’s review Streamline. It is worth noting that a cheap day return from Wrexham to London cost ten shillings (50p) at that time.

15th March 1935

I applied for the police force last Monday. I have also applied for a post as police inspector in the Colonies. It would be absolutely great if I could obtain one because commencing salary is about £350 per year.

I also applied for the new police college which the Metropolitan Commissioner of Police Lord Trenchard (the founder of the RAF), was establishing at Hendon in 1935. I seem to remember that a successful graduate would do six months ‘on the beat’ before becoming a subinspector.

When I went up to London for the interview at Scotland Yard I was told that I was too young, but could be interviewed again the following year. With the object of looking older I decided to grow a moustache. It was pretty awful – gingerish – but I persevered with it for some time.

I should mention here that in the RAF during the war I met many graduates of Hendon Police College. They could always be spotted by their smartness and bearing. Amongst those who reached air rank were Air Chief Marshal Sir William Coles, Air Commodore Paddy Kearon and Air Commodore Bill Stewart, who were all friends of mine. Like them, I feel sure that I would have left the Metropolitan Police in 1939 to join the RAF.

On arriving back in Wrexham, I realised that I was going to have to earn some money and with skills learned both from my father and from books, I decided to be an electrician. Undercutting the opposition, I charged only £1 for installing a lighting point, on which I made about 2/6d profit (12^p from 100p). It was almost always a dirty and time-consuming job. I also repaired shoes and mended bicycles. One day after I had mended a puncture for Het, her mother told her that she should not allow me to help her again. She warned her that: "she must not be beholden to strange boys!"

My early interest in aeroplanes had been whetted by seeing Britain win the 1928 Schneider Trophy race at Calshot, when I was on holiday with my relations in Wiltshire. I was astonished and amazed to witness seaplanes going so fast. I had also attended two of the annual RAF displays at Hendon where I had marvelled at the skill of the pilots. During those years I had taken every opportunity to cycle the fourteen miles from my home to RAF Sealand, a flying training school. There I had a close view over the hedge of aircraft being made ready to fly by their instructors and pupils and of take-off and landing practice. Thus in the spring of 1935 I was overjoyed to read that suitable applicants would be considered for short service commissions in the RAF. ‘short service’ meant four years followed by a gratuity of £300. I filled in and forwarded the necessary forms. Het’s father signed a form as guarantee of my good character. As a result I was summoned for interview at the Air Ministry in London. At Adastral House, Kingsway, then the home of the Air Ministry, I went before a panel of five or six officers before being subjected to a rigorous medical examination.

To my delight, quite soon after I received a letter informing me that I had been granted a short service commission but that, ‘it was doubtful whether I would be called upon for duty before August’. In a letter to Het I wrote: ‘I have been walking on air all day long, isn’t it a good job that I failed to get into the Metropolitan Police.’

A short time later I received my marching orders requiring me to report to the Bristol Flying School at Filton, before noon on 26th August next. While at Bristol I would undergo my ab initio training, a course of elementary flying where I would have civilian status. If my flying proved satisfactory I would, after six weeks, be posted to the RAF depot at Uxbridge where I would be commissioned as an acting pilot officer on probation. I wrote to Het:

I have to fill in numerous forms. The first of these my father saw had on it ‘name of relative we are to correspond with in case of casualty’. They have given me detailed instructions as to what I have to wear while at Bristol: lounge suits, sports jacket and slacks, dinner jacket suit, full evening dress (tails) etc. They have also told me what I have to wear when I go to Uxbridge and have my uniform. I am not to wear service slacks there – but have to wear breeches.

That August I camped at Rhyl for ten days returning to Wrexham for a few days before leaving by train for Bristol on Sunday 25th August, arriving at Filton at six in the evening.

LEARNING TO FLY AUGUST 1935-MAY 1936

Filton, just outside Bristol, as well as being the location of the Bristol Flying School, was the home of The Bristol Aeroplane Company, makers of aero engines and of the Bulldog and Gauntlet fighters. The City of Bristol RAF Auxiliary Squadron, flying Sidestrands, was also based on the airfield.

Civil flying schools had been set up for the basic training of pilots due to the inability of the RAF to cope with the number of pilots needed to satisfy the recent decision to expand – proof the government at last was seeing sense. Director of Flying Cyril Unwins, was also the chief test pilot of Bristols, and was famous for his high altitude flying; he was the first man to fly over Everest. The flying and ground instructors were mostly ex-RAF. My instructor, a most likeable chap, was Flying Officer Ellison, then a twenty-six-year-old reserve officer.

We aspiring pilots were fifteen strong; five were ex-RAF boy apprentices from Halton and Cranwell who were due to become sergeant pilots. These had already served in squadrons for about six years as fitters, armourers, wireless operators etc. The rest of us, who were due to become officers, were a varied lot; some straight from school, others older, who had been dissatisfied with their jobs in civilian life and two ex-Mercantile Marine officers who were unable to get jobs in the merchant navy which was then in decline because of the state of the economy.

We prospective officers lodged in a house called Brooklands, situated next to the aerodrome, while the ‘would be’ sergeant pilots had to find other digs because NCOs were not allowed to associate with officers. I wrote in a letter to Het, ‘the fellows here are all jolly good sports’. Other than me, all of those destined to be officers had been at public schools, but there was no noticeable class divide. Two of them had their own cars while another two had had their licences suspended, for ‘driving in a manner dangerous to the public’. In general we operated as a group and together visited the better pubs in Bristol.

I wrote to Het on my first evening:

I have become a club member of the flying school which cost me two and sixpence and consequently I have a wonderful lunch of five courses with coffee in the lounge afterwards for one and sixpence and afternoon tea costing six pence.

I remember being somewhat apprehensive before my first flight in a Tiger Moth on Tuesday 27th August 1935. Although this was my first ever flight – and, despite my instructor subjecting me to stalls, rolls and loops, I revelled in it and showed no signs of air sickness. I wrote to Het that evening, ‘I had a wonderful time of it today’.

7th September 1935 was a great day in my life. After twelve hours and fifteen minutes dual flying, I went solo for twenty minutes flying at 300 feet. In my log book I wrote: ‘Taking off and landing – what a fortunate Tiger’.

We flew everyday and also attended endless lectures on the principles of flight. For me flying was the main excitement and challenge. In retrospect however, I was rather foolish to ‘chance my arm’ by flying under the Clifton Suspension Bridge!

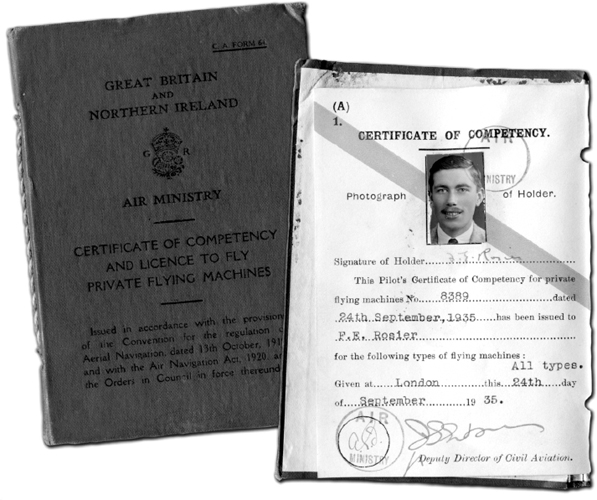

On 24th September I received my Certificate of Competency and ‘A’ licence (No. 8389) after thirty hours flying, twenty dual and ten solo. I also noted in a letter to Het, ‘I am slightly out of funds as I bought a sports jacket yesterday for thirty-five shillings’ (or £1.75).

On 11th October I completed my first solo, cross country flight from Filton to Andover and return in ninety minutes. Three days later I had a flying test with T W Campbell, the chief flying instructor. This I passed, thereby completing my ab initio training course. I left Filton on 17th October after seven weeks, and fifty-two hours flying.

After a few days’ leave those of us who had passed the course moved on to Uxbridge, the RAF depot, where on 21st October we were gazetted as acting pilot officers on probation. There we were joined by other groups who had completed their initial training at other civil flying schools. Many hours over the next two weeks were spent drilling on the parade ground where we were turned from a rabble into a reasonable bunch of men. It was here that we had our first introduction to service life. We were made to study, and to laboriously amend the King’s Regulations. We were briefed on service etiquette and were given practical guidance on how to behave in the mess.

On Thursday we have a guest night to which the RAF band attends. Drinks are first served in the anteroom. Then we go in to dinner during the course of which we are not allowed to mention ladies’ names, politics or religion.

On the first day (Monday) we had orders to proceed into London after lunch and go to the tailors to be measured up for our uniforms. I went to Moss Bros in Covent Garden with six others. We went into London again on Wednesday for the first fitting and again on Friday for the second. The uniform altogether will cost £65.

My complete kit, which arrived before I left Uxbridge, comprised flying boots, shoes, socks, shirts (including stiff shirts), service uniform, breeches and puttees, greatcoat, mess kit including two waistcoats – one for formal wear – mess wellington boots and a tin trunk. My uniform allowance covered the lot.

On passing out from Uxbridge on 3rd November I became 37425 Pilot Officer F. E. Rosier. From Uxbridge the whole course of about thirty short service commission officers was posted to No.1 Course at the newly-established 11 Flying Training School at Wittering, three miles south of Stamford in Lincolnshire. I was posted to B Flight where my instructor was Sergeant Johnson. The Central Flying School (CFS) had vacated Wittering and returned to Upavon where it had been founded in 1915.

Our curriculum was divided between classroom, workshops, the barrack square and flying. The aircraft we used was the trainer version of the Hawker Hart light bomber, a bi-plane with an open cockpit, powered by a Rolls-Royce engine. The pupil sat in the front cockpit, with the instructor behind him. In comparison with the Tiger Moth it was powerful and fast, cruising at about 150 mph. 13th November was another red letter day: I went solo on the Hart.

At Wittering, as well as work, there was plenty of time to play sport and I played rugger for the 1st XV regularly. One of the members of the course, Tom Dalton-Morgan, a very good scrum half, used to drive me to Leicester to spend an occasional evening with Het who was by then teaching at a school near Coalville. Tom, a close friend of mine, had a distinguished war record. He commanded 43 Squadron in the Battle of Britain and later as a group captain on the operations staff of 2nd Tactical Air Force was an exceptionally gifted staff officer. Unfortunately he was a ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ figure who in 1952 ultimately had to leave the service.

On 20th January l936 I lost three months’ seniority (and some leave) for disobeying orders forbidding us to do aerobatics. On a passenger test with my fitter, LAC Williams, I rightly thought that no one could see what I was doing above the clouds. I was not to know that my fitter would be so violently sick that when we landed he would have to be lifted from the aircraft. Whilst he was led away I was ordered to clean up the back cockpit. However, this incident was luckily soon forgotten and on 25th January I was authorised to wear my ‘flying badge’ or ‘wings’.

My great ambition was to become a fighter pilot and it was therefore a very proud moment when I was transferred from the Hart trainer to C Flight to fly the Hawker Fury.

My first flight in a Fury – K1937 – was on 20th February, and a month later I recorded in my log book on 24th March that I ‘led a formation on a battle climb – time to 16,000 feet – eight and a half minutes’.

The last month of our flying training was spent at an armament training camp at Catfoss, north of Hull, where we fired at ground targets and at ‘sleeves’ towed behind our aircraft. On our return to Wittering on 20th April I was graded ‘above average’ as a pilot, and what was even better news was told that my next posting was to be to 43 (F) Squadron at Tangmere. I could not have wished for better for 43 – ‘The Fighting Cocks’ – was one of the most famous fighter squadrons in the RAF.

At the same time, a great friend of mine, Johnny Walker, was posted to 1 (F) Squadron, also famous, and also at Tangmere. So after twenty-nine hours and thirty minutes solo on Furies, on 6 th May I set off for Sussex. Little did I know when saying goodbye to Wittering and the medieval town of Stamford that I would return there in August l940 during the Battle of Britain.