THE WORLD’S FINEST FLYING CLUB

43 SQUADRON AT TANGMERE MAY 1936-AUGUST 1939

Tangmere is situated three miles from Chichester, close to the south coast, and importantly south of the Downs. As a resuit it has one of the best weather factors in the country. Having been the home of both 1 Squadron and 43 Squadron since 1926 there was great rivalry between the squadrons both at work and at play.

I spent the next three years at what was affectionately known as ‘Tanglebury’ with what was without doubt one of the finest squadrons in the RAE At that time 43 Squadron held both the trophy for gunnery and the Sassoon trophy for the annual pinpointing competition. The first two of these years were carefree when I felt that I belonged to one of the most exclusive flying clubs in the world. The third was the year we exchanged our Furies for Hurricanes and prepared for a war that seemed inevitable.

43 Squadron had two flights, each with six Furies, powered by a 580 hp Rolls-Royce Kestrel V-12 supercharged, water-cooled engine. I was posted to B Flight, commanded by Flight Lieutenant J W C ‘Hank’ More who was an exceptional pilot, and also a world-class squash player. A Flight was commanded by Flight Lieutenant R I G MacDougall who was also the acting squadron commander. My first flight in a Fury from Tangmere was on 13th May 1936.

For the first few weeks Johnny Walker and I, whilst treated reasonably in the mess, were seldom invited out to parties, pubs and visits to local towns by the other officers in the squadrons. Had it not been for Johnny’s car (I could not afford one), we would have been limited to playing squash together, staying in the mess, or walking the three miles to the Dolphin, situated just opposite Chichester Cathedral. Incidentally, I once damaged Johnny’s car when I went into a ditch, having gone too fast around a bend. I did pay for the repairs however. After a few weeks that ‘treatment’ in the mess came to an end when we were told that we could wear our squadron ties. We had been accepted. In those days it was normal for newly arrived officers to undergo a period of probation.

A little bit about the daily routine: the batman I shared with another officer would awaken me with a cup of tea at 7.00 a.m., the curtains would be drawn, the bath filled, my clothes for the day laid out, and my shoes polished. After breakfast I would go down to the flight office and we would then fly two or three times a day. The summer routine was to rise at 6.00 a.m. and to work until 1:00 p.m., leaving the afternoon free for sports and for sailing at West Wittering and Itchenor.

My log book for June 1936 lists some of the training carried out that month as: ‘Camera gun attacks on other aircraft, instrument flying, formation flying, cross country flights, pinpointing, slow flying and spinning, message bag dropping, battle climb to 25,000 feet with full war load and high altitude flying.’

Mess kit – blue waistcoats – was worn for dinners in the mess on Mondays, Tuesdays and three Thursdays in the month; the remaining Thursday being regarded as ‘formal’ at which full mess kit – white waistcoats – was worn. On Fridays we wore dinner jackets and on Wednesdays, Saturdays and Sundays, it was tweed jackets.

The food in the mess was excellent. My pay as a pilot officer was about £18 a month; out of this my mess dues covering subscriptions, food and drink came to £8 and my tailor’s bill to £2, leaving about £8 spending money. This sounds very little but £1 could buy over forty pints of beer or twenty-three packets of cigarettes. For £5 I could have a good night out in London and return with some change.

A couple of months after arriving at Tangmere, on 8th July I was detailed to give a flypast and solo aerobatic display at Andover for General Milch, the inspector general of the German air force, and some of his senior officers, who had been visiting the RAF Staff College. Towards the end of the display my engine cut out whilst I was doing an upward role. I attempted in vain to restart it by putting the Fury into a dive and soon realised that I was left with a long glide to the airfield. In trying to stretch the glide, in full view of the high-powered spectators, I stalled and spun in whilst attempting a forced landing. I thought I had broken my legs in the crash but in the event I sustained nothing more than bad concussion. I was flown in an obsolete Virginia to the Royal Navy Hospital at Haslar, near Lee-on-Solent. I forget how long I stayed but I know that I was back flying by 22nd July, thirteen days later. Incidentally, Het has always maintained that this incident was one of the reasons the Germans considered that the RAF would be a ‘push over’.

Whilst on sick leave I went by bus from Liverpool to Windermere to see Het who, with a few old college friends, had organised a hike in the Lake District. They were staying in hostels run by the Youth Hostels Association which had only been founded in 1929 but was already growing rapidly in numbers and popularity, probably because the cost was only one shilling (5p) for a night’s lodging. I spent the three nights sleeping under the stars under blankets smuggled out to me by the girls.

On occasions we practiced with the army and I note from my log book that, on 1st September I flew to Old Sarum with Flight Lieutenant More and Pilot Officer Bitmead where we made ‘low flying attacks on the Tank Corps’. In the remarks column I wrote ‘a brush with the military’.

We practiced formation flying endlessly and had a flight aerobatic team, where we flew in diamond formation, which consisted of Flight Lieutenant More, Pilot Officer Bitmead, Pilot Officer Hollings and myself. We also practiced squadron formations and on 29th October we carried out a flypast in squadron formation for the AOC’s annual inspection.

For our long weekends I was sometimes allowed to take my Fury away. Mostly I flew to Sealand, refuelling en-route at Bicester. My destination was Wrexham. I stayed at my home in Rhosddu but spent most of my time with Het.

On 30th October, on one such mission, I flew cross country to Sealand to see Het for the weekend. I was flying in a Hart and was accompanied by Pilot Officer Hollings in a Fury. We hit bad weather nearing Sealand, and Hollings, who was formating on me, lost contact with me in thick cloud. On landing I was told he had crashed near Hawarden in thick mist and had been killed. Three days later I attended his funeral at Stockport.

The Court of Enquiry, at which I was accompanied by Flight Lieutenant More, was held at RAF Northolt and little blame, if any, for the accident must have been apportioned to me for in December I was asked to take over command of B Flight from More. He had been posted to the Fleet Air Arm, and went on to distinguish himself as the squadron commander of 73 Squadron in France in early 1940. He was later posted to the Far East where he became a prisoner of war, and was lost when a Japanese ship full of prisoners, en-route to Japan, was sunk by an American submarine. Much later in 1962, when he was an admiral in Bahrain, I met that submarine commander – Rear Admiral Eugene Fluckey, known as ‘Lucky Fluckey’. He was a frequent visitor to Aden where I was stationed.

At the age of twenty-one and a flight commander with 43 Squadron, life for me could not have been better. I was a member of the finest flying club in the world. In my flight I had very good pilots and the ground crew had tremendous spirit. We worked hard and the social life was hectic. Sports, which took up much of our spare time, included rugger, squash, golf, tennis and cricket and in the summer we regularly went to the beach at West Wittering and sailed from Itchenor. Once in 1938 I played at Arundel Castle for the Duke of Norfolk’s XI against the ‘Sussex Gentlemen’.

In February 1937 Squadron Leader R E ‘Dickie’ Bain took over command of the squadron and I wrote in a letter to Het that I played golf at Goodwood on Sunday 21st February with Caesar Hull and Johnny Walker. That year I had hoped to win selection to carry out the single aerobatic display at the annual Hendon Air Display, but I was ‘off flying’ due to illness on the day in late April that the inter-squadron competition was held.

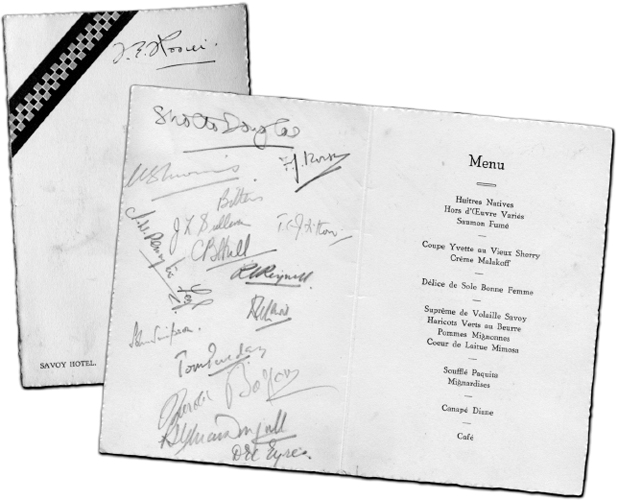

A highlight of the year was the squadron reunion dinner held at the Savoy on 16 th April, attended by former squadron members Sholto Douglas and Harold Balfour, later Lord Douglas of Kirtleside and Lord Balfour of Inchrye.

The Savoy menu, signed by the squadron members at the reunion dinner

I noted in a letter to Het that 9th June was ‘a full day’s holiday for the King’s birthday and we spent nearly all the day on the beach’. Further highlights were the squadron formation of fourteen machines at the Empire Air Display and the summer exercise in August when my flight intercepted and attacked a flight of five Hinds at 10,000 feet over Petworth. In October I flew to North Weald with Caesar Hull and Eyres to take the promotion examinations. Later that month on 27th October we went to Warmwell in Dorset for our annual armament training camp. The live firing took place at Chesil Beach and I averaged 149, the highest score in the squadron. During the camp however, I hit a drogue, damaging the centre section of my Fury and forcing me to land close by at Chickerell near Weymouth.

In 1937 my contemporaries from 43 Squadron in the mess, which we shared with 1 Squadron were Pilot Officer Caesar Hull, a Rhodesian by birth who had been brought up in South Africa and who was killed in September 1940 while commanding the squadron; Pilot Officer Ralph Bentley, who twenty-five years later was chief of the air staff of the Rhodesian Air Force when I was AOC in Aden; the Canadians, Pilot Officers Joe Sullivan who was killed in France in May 1940, and Pat Christie; Malcolm ‘Crackers’ Carswell, a New Zealander, and the British contingent, John Simpson, Eyres, Bitmead, Folkes and Cox who was killed in the Battle of Britain.

In addition to the officers there were several sergeant pilots in the squadron. Most notable of these were ‘Killy’ Kilmartin, Frank Carey, a very good rugby player who had an outstanding war record and was later to be commissioned, retiring in 1962 as a group captain, and Jim Hallowes.

In January l938 I was sent on an air-firing instructor’s course at Sutton Bridge with Johnny Walker of 1 Squadron. Later that month I spent a weekend with Caesar Hull and Johnny Walker at John Simpson’s house in Essex which he shared with Hector Bolitho. In the grounds they had made their own air strip. During the weekend we visited Cambridge and Saffron Waldron.

In January and February 1938 we did a lot of night-flying in Demons in order to be fully trained when we got our Hurricanes. On 28th March I noted that, with John Simpson and one other, I flew cross country from Tangmere to Grantham for morning tea and refuelling, and then on to Catterick for lunch. After lunch we returned via Hucknall making a detour to Coalville in Leicestershire where Het was still teaching.

Our weekends were always free unless we were duty officer. One Saturday in 1938 I drove up to Coalville on my newly-acquired motor cycle to see Het and to take her up for her first flight. I managed to get a Tiger Moth from Desford, the local flying club, took off and began to show her how good a pilot I was. It was not long before she started to feel sick and in the hope that it would make her feel better, I told her that I was uncertain of our position and that her job was to tell me the names of railway stations we were flying over. It worked. The motor cycle did not. On the way back to Tangmere it broke down. I never rode it again.

In May 1938 we took part in an Empire Day flying display and on 25 th June after much practice, we carried out a squadron formation air drill at an air display held at Gatwick organised by the Daily Express following the demise of the annual Hendon Air Display. The day was very windy and we had great difficulty maintaining the line abreast flypast. That summer I led six Furies in what was the official RAF Aerobatic Team and little did I know that this was to be the swansong of the aerobatic Fury.

For the first two weeks of August we went on our annual air firing/armament camp at Aldergrove in Northern Ireland where I wrote in my log book that I scored 420 and 390 which caused ‘repercussions that night – Squadron Leader Hall’s rye whisky’.

Although rumours of war abounded on our return we went on summer leave and four of us – Caesar Hull and ‘Crackers’ Carswell from my squadron and Mac Boal, from the newly arrived 217 General Reconnaissance Squadron (with Ansons) – chartered a 26 foot cutter. With plenty of food and drink aboard, we set off one evening from Itchenor for Dieppe. Less than an hour later the engine seized, forcing us to anchor for the night. Next morning, having agreed that we would continue using the sail alone, we made fast progress across the Channel. All went well until nightfall when we lost our dinghy as the tow-rope had parted. Nearing the French coast, we were led into the harbour of St. Valéry en Caux by a friendly local yachtsman.

We stayed in St. Valéry for two days and on the third day, having decided that we had drunk far more ‘vin blanc cassis’ than was good for the liver, we left. Once outside the harbour before setting course, we fired off a distress rocket to acknowledge the kindness of the locals.

Our destination was Ouistreham where we had promised to meet Sergeant Kilmartin, who was participating in a cross-channel race. Unfortunately, the weather deteriorated fast and west of Le Havre in the area of ‘Rochers du Calvados’ the wind was so strong that we had to reef the sails. However, the fates were looking kindly on us for we were sighted by a French trawler which, with great difficulty, managed to get a line to us. There followed several tense hours of wondering whether our boat would stand the strain of being towed in rough seas; but all went well and we were towed into Ouistreham harbour.

Deciding that we had enough francs for two or three days in Paris we set off there by train the next day. Paris was wonderful. We did the rounds of Montmartre and Montparnasse by night and by day. However, the news in the papers of possible war and the sight of sloppy French soldiers in the streets convinced us that we had better get back to the UK and Tangmere. Arriving back at Ouistreham our boat was a pitiful sight but, with continuous baling, we managed to cross the Channel, reach Itchenor and beach the boat. There was much argument as to how much we owed the owner. Eventually we paid nothing, as his insurance saw to it.

On our return to Tangmere on 29th August preparations had started in earnest to put the station and the squadrons on a war footing. All our machines were made serviceable so that they could leave the ground within three minutes of an alarm. A few weeks later on 26th September, I noted in my log book, ‘Recalled from Sealand owing to crisis. Crisis week – efficient flapping’. We bought dark green, dark earth and black paint in Chichester and to our dismay camouflaged our beautiful silver Furies. The sparkling white hangars of Tangmere were painted drab greens and browns and air raid shelters were built. The aerodrome itself was camouflaged to represent hedges, ploughed fields, roads, haystacks etc. In addition, as the Fury was immediately designated night operational, as well as day, torches were bought with which to see our instruments in the dark. They may have been of some help in half-light, but in the dark the flames from the short stub exhaust pipes restricted our night vision. In this regard it should be noted that the Fury had no navigation lights, no signalling lights and no illumination in the cockpit (i.e. the dials were not luminous).

Thank God the war did not start in 1938. On 30th September Chamberlain came back from Munich proclaiming ‘Peace in our Time’ which gave us another year to prepare for war. As a fighting service to be reckoned with the RAF was unprepared. Admittedly, squadrons were beginning to be equipped with the new eight-gun Hurricanes and a few Spitfires, but they were slow in coming. Had war started that autumn, we would not have stood a chance in our Furies, by then the slowest fighter in the RAF. Even against bombers they were not fast enough.

But at last, towards the end of 1938, the great day came when 43 Squadron was presented with Hurricanes. On 18th November I did my first solo in Hurricane L1690 ‘wheels down’, and on the morning of 29th November, having flown to the Hawker factory at Brooklands in a Demon with Squadron Leader Bain, I collected one of 43 Squadron’s first two Hurricanes L1725 and flew it back to Tangmere. I soon felt at home in it and was excited by its performance – with a top speed of 318 mph it was fifty per cent faster than a Fury – and by its armament of eight Browning.303 machine guns.

We then spent the next few days doing ‘high drag’ flights, i.e. with wheels down and cockpit hood open, until by mid-December the full establishment of sixteen Hurricanes had arrived.

On 7th December in order to show off our new aeroplanes several of us flew to Debden in Essex for a cocktail party, which was unfortunately marred by George Feeny force landing in a nearby field.

On 6th January 1939 we carried out our final squadron formation in our Furies and a few days later I flew to Castle Bromwich in a Hurricane where I had been given the job of assessing the resident airfield of 605 Auxiliary Squadron in its suitability for operating Hurricanes. On arrival there I was met by the squadron assistant adjutant who introduced himself as Pilot Officer Smallwood, to which I am told, I pompously replied that I was Flying Officer Rosier. Without exception the auxiliaries gave me a warm welcome. One in particular, Flying Officer Mitchell, of Mitchell & Butler the Midlands brewers, lent me his expensive car for a few days. ‘Splinters’ Smallwood and I became close friends until as Air Chief Marshal Sir Denis Smallwood he died in 1997.

My stay at Castle Bromwich was longer than I anticipated because I had to wait for suitable winds to trial take-offs and landings in the required directions. It was during this time that I attended a local funeral of a Tangmere NCO who had been killed in an aircraft crash. Splinters and I went together – he as the 605 Squadron rep and I representing 43 Squadron. After the funeral we were taken along to the parents’ house for an Irish ‘wake’, which was something new to us. In no time we were under the influence with never-ending Guinness, whisky, etc consumed in an atmosphere quite the opposite to that which we had expected.

In February l939 our Furies finally departed to the maintenance unit at Kemble. My last flight in a Fury was on 21st February when I noted in my log book, ‘last flight in Queen of North and South. Perfect’.

Three other events that spring were of particular importance to me. The first was that in January I heard that I had passed the examination for a specialist permanent commission. Out of the 250 who took the exam I came thirteenth. Having to choose between navigation, signals, armament and engineering, I decided on the latter. It would entail a two-year specialist course at the RAF School of Aeronautical Engineering at Henlow in Bedfordshire, followed by a further year at Cambridge University. Caesar Hull and Johnny Walker from Tangmere were unlucky.

The second was that in February 1939 the promotion of Peter Townsend to flight lieutenant resulted in him taking over command of B Flight, which I had commanded for over two years, and I became adjutant while remaining attached to B Flight. Although I must admit to having felt somewhat put out by this change, I accepted that Peter’s seniority gave him the right to be a flight commander. I liked Peter although he was difficult to get to know as he was very shy and rather aloof. In his book Duel of Eagles Peter writes of a ‘wake’ which took place in the mess on 22nd April 1939, the night that Flying Officer John Rotherham was killed in an accident while we were night-flying. There we got slowly drunk as I played ‘Orpheus in the Underworld’ on my violin.

The third, and most important of all, was that on 1st April Het and I were engaged to be married.

My last few months with the squadron that spring and summer were spent training hard for a war which we all felt was by now unavoidable. During this time, for training purposes, I occasionally flew the squadron’s dual-controlled Fairey Battle. We endlessly practiced aircraft interceptions, air-firing, instrument flying and battle climbs under operational conditions. On Empire Air Day, the 20th May, a huge crowd came to Tangmere to see the new Hurricanes carry out an aerobatic display.

In early August 1939 43 Squadron was involved in the United Kingdom air exercises held in conjunction with the French air force. They played the enemy, and during the action I carried out a battle climb to 32,000 feet with Pilot Officer Folkes and Sergeant Berry.

The squadron was ‘mobilised’ on 5th August, by which time I had handed over as adjutant to John Simpson and my last flight with 43 was on 17th August when I recorded in my log book, ‘war inevitable’.

I left the Fighting Cocks with great regret. My three years at Tangmere had been marvellous and I hated leaving my many friends there. I also hated the idea of not flying with those friends in the war which was clearly about to start.

I had commanded B Flight for two years as a pilot officer and a flying officer whilst the normal rank for the post was flight lieutenant. I believe I was the first to organise and lead a flight aerobatic team of four; three in V formation and one in the box behind. During my two years in command I had the good fortune to have had very good pilots, Pilot Officers Bentley, Eyres, Simpson, Sullivan, Cox, Folkes and Christie, and Sergeants Hallowes, Shawyer, Berry, Hall and Carey. Sadly, most of them did not survive the war. I also had dedicated maintenance crews from the most junior airmen to the flight sergeants.

However, all the pilots and I were highly critical of the restrictive operational training we had to follow. It was assumed by the ‘powers that be’ that training in fighter combat was unnecessary because the range of German fighters operating from their home bases would not allow them to escort bombers attacking the UK. The result was that provision was made only for close formation flying and set attacks against bombers. This meant that dog fighting practice – fighter v fighter – was out. But we sometimes used to manage it when the CO, Dicky Bain, an ‘ancient’ thirty-seven year old, was away. He was not there to see the resultant oil marks on the wings which were ‘incompatible with peacetime standards of cleanliness’.

HENLOW AND 229 SQUADRON SEPTEMBER 1939-MAY 1940

The course at Henlow started on 27th August. One of the first people I met was Flying Officer Cedric Masterman, who had just returned from the North West Frontier. He was to become David’s godfather, and a life-long friend. The engineering course was a great change from squadron life, but I soon settled down, made new friends, and set to work with a will.

For the first practical task we were given a piece of metal, measuring devices and some files, with which we had to make a spanner. I was so pleased with mine that I had it plated and took to carrying it as a lucky charm in the top left pocket of my uniform jacket. It must have worked for I survived the war. Sadly, it was stolen just as the war ended.

Within a week of the course starting came Neville Chamberlain’s broadcast on 3rd September with the grave but exciting news that we were at war with Germany. It did not take long before my new friend Cedric Masterman and I, determined to get back to active flying, came to the conclusion that slacking at work and bad behaviour were the means to accomplish this. From being near the top of the course we were soon bottom; we drank too much and even failed to stand to attention when the national anthem was played.

It was not long before the commandant, an air commodore, sent for us. He said it was clear enough what we were up to but it was now time for us to return to normality because there was absolutely no chance of getting off the course and returning to squadron flying. Leaving his office we said, "Bloody old fool" and continued with our bad behaviour.

Het and I had been engaged for some months (since April Fools’ Day!) and we thought, with the start of the war, that it was time to get married. I made the arrangements with the vicar of Henlow Parish church and on Saturday 30th September, by special licence (at a cost of £25), we were married at the church of St. Mary the Virgin. Cedric Masterman was my best man and Stewart, Het’s brother, gave her away. Members of the course provided the Guard of Honour. Sadly, for operational reasons, no-one from 43 Squadron was able to attend the wedding. However I still have the telegram sent by the adjutant, Flying Officer Simpson: ‘Good luck and congratulations to you both from all in 43.’

Following the ceremony we drove away in Cedric’s Wolseley sports car to the mess at Henlow and drank champagne. Later that evening we were guests at a dinner at the George and Dragon in Baldock. It was a merry party and it still amazes me how we found the way to our first home, a dreary flat in Garrison Court, Hitchin.

The next morning we awoke to the noise of pebbles, thrown by some of my friends, hitting the bedroom window. They took no notice of my shouting “push off” but with much laughter told me that I was posted. I thought they were pulling my leg but later, upon our arrival in the mess, I saw that it was true. The posting notice simply stated that with immediate effect I was to proceed to 52 Operational Training Unit (OTU) at Aston Down, in Gloucestershire in the rank of flight lieutenant.

So, on the Monday I returned my wife of less than two days to her mother. We parted, on platform one of Paddington Station – she for Wrexham and I for Swindon and then Stroud.

But my posting to Aston Down was short lived. Two days later on Wednesday 4th October, as I was buying a car, I was telephoned and told to report with all my luggage to Air Vice-Marshal Leigh-Mallory at his 12 Group HQ at Hucknall, at 9.30 a.m. the following morning. "Night-fighters will be important in this war," he said, "... and I am sending you as a flight lieutenant to be a flight commander on a Blenheim night-fighter squadron, No.229 being formed at Digby."

I left for Digby in Lincolnshire straight away and as soon as I arrived sent Het a telegram which she received just as she was about to leave for Aston Down. The message was: ‘Stop – Ring Metheringham 26’. She found out where Metheringham was by cycling to the post office and they were able to confirm it was in Lincolnshire.

On my arrival at Digby I found that with the exception of the squadron commander, Squadron Leader Harold ‘Mac’ Macguire – a grand chap, straight from flying boats in Singapore – I was the only other officer in the squadron.

229 Squadron was officially formed (on a one flight basis) on 6th October and on the 14th information was received that a second flight was to be formed.

Over the next week a second flight commander, New Zealander Flight Lieutenant Clouston, and the rest of the pilots and gunners who had come straight from flying training school, where their courses had been drastically curtailed, arrived. The majority were only eighteen or nineteen and they had initially been trained for bombers. One hundred per cent casualties were expected in the first three months.

I was OC of A flight and made my first flight in a Blenheim on Tuesday 17th October. My flight consisted of Pilot Officers Bussey, Simpson, Brown, Linney, Smith, Lomax and Dillon.

The next few weeks were spent training, with lectures and with the pilots getting as much practice as possible on the Link Trainer.

The only difference between the so-called ‘night-fighter’ Blenheim IF and the standard bomber model was that it had a pack of four forward-firing guns fitted to the bottom of the fuselage. The crew consisted of 1st and 2nd pilots and a mid-upper gunner. The Blenheim, which had two engines, had a bad reputation for single-engine failure just after take-off, often resulting in fatal crashes. They occurred because pilots were not taking proper corrective action. Our first task, therefore, was to demonstrate the proper action to be taken, followed by practical tests. As a result of this exercise we eliminated accidents from this cause.

My log book entries for the next month were brief:

2nd November

The King visited Digby and 229 Squadron, being without aircraft, paraded on the road behind the watch office where they were inspected by HM.

6th November

Four Blenheims were received. Spitfire of 611 Squadron ran into 8722 while it was taxiing towards hangar.

8th November

Three more Blenheims arrive.

10th November

Flying training commenced.

15th November

Three more Blenheims delivered.

24th November

Night-flying by Squadron Leader Macguire and myself.

28th November

Five more Blenheims arrived.

Although the winter of 1939/40 was very bad – cold and with lots of snow – we took every opportunity to train by day and night with the object of attaining operational status as soon as possible. It was during this period that one weekend I met Het at Nottingham station where she had come from Wrexham. On arrival at a hotel called the Flying Horse we signed the register and went to our room. Soon there was a knock at the door – the manager wanted to see us. He produced the register, pointing out that a Blackwell and a Rosier could not stay together in the same room. Het had absentmindedly signed her maiden name. She never made the same mistake again!

229 eventually became operational on 21st December and I recorded in my log book: ‘The war starts for fighting 229. Red Section A Flight carried out first operational duty’.

From then on we carried out patrols over the North Sea, mostly to protect convoys and fishing vessels. These were known as ‘kipper patrols’. On Christmas Eve I was returning from one such patrol when I lost an engine. With no hydraulic power from the failed port engine it meant that the undercarriage had to be pumped down by hand – an arduous and time-consuming job. Choosing to land at Bircham Newton in Norfolk, where the visibility was better than at Digby, my copilot Pilot Officer Brown pumped and pumped frantically and the undercarriage locked down before we touched down.

Het had arrived that day to spend the Christmas holidays at Digby. When she arrived at Lincoln station after a slow and tedious journey across England, she was surprised not to be met by me but by a young squadron pilot. She said he was a bit inarticulate as, at that time, I was ‘lost’. Finally, I was found at Bircham Newton. I was not able to return to Digby until the afternoon of Christmas Day. We usually stayed together at the Saracens Head, Lincoln, but Het spent that Christmas night with the station padre’s family at the vicarage at Scopwick.

Two days later on the night of 27th December, on another patrol I was told that a Dornier 17 was in the vicinity. My gunner spotted him flying east at about 25,000 feet. I gave chase, using full power to climb from 1,000 feet and managed to get to within half a mile of him before he saw me and pulled away. I remember the occasion well because I was not dressed for the extreme cold at night and it took a long time for me to thaw out. I had never experienced such freezing temperatures; it was a lesson to me.

In January we took it in turns with B Flight to deploy to North Coates near the Lincolnshire coast where we maintained a state of readiness. Our role was mostly to carry out convoy patrols. We were rarely called upon to ‘scramble’ and when we did the missions were uneventful.

I remember vividly one very dark night that January when it started to snow heavily. One of our aircraft, captained by Pilot Officer Bussey, was overdue and radio contact with him was lost. I feared the worst. But shortly afterwards we heard the sound of his Blenheim. It was still snowing and the visibility was poor but he found the airfield and made his approach. Then he spoiled a very good show by landing with his undercarriage up. His excuse to me a few minutes later was, "I’m sorry Sir, but you can’t expect me to remember everything."

Coincidentally, Het’s brother Stewart Blackwell who had enlisted as an NCO in the RAF at the outbreak of war was posted to North Coates in February 1940 where I saw him on several occasions.

On 24th February 229 had its first casualties when Pilot Officer Lomax crashed and all three crew members were killed while night-flying doing ‘search-light cooperation’.

At the beginning of March 1940 the powers that be ordained that we convert from night-fighters to day-fighters, and in our case we started flying Hurricanes. On 7th March I collected my Hurricane (L2141) from 213 Squadron at Wittering. Others were taken over from 56 Squadron at North Weald which had received the new tin-winged version. We said goodbye to our gunners, a stalwart lot, and started to convert our pilots to single-engine aircraft using the Miles Master Trainer. On 15 th March the AOC-in-C Air Marshal Dowding visited the station and questioned the squadron leader concerning the re-equipment of the squadron.

Within seven days we reckoned that the pilots were ready to fly the Hurricane but it then took three weeks of hard work to train them up to a reasonable standard before we were declared fit for ‘day’ operations on 26th March.

During March and April training was interspersed with periods of readiness at our forward base at North Coates where we were sometimes ordered to patrol over the North Sea. On 30th March I noted that we intercepted a raid in the early evening. Our early version Hurricanes were fabric covered, and had no armour plate fitted behind the cockpit and no self-sealing tanks intended to minimise the risk of petrol fires. Later Hurricanes had these modifications as standard.

In early April I wrote to Het and told her in great secrecy that 229 Squadron would be moving to a new RAF station at Kirton-in-Lindsey on 15th and 16th May. Little did I know that in fact my next move would be to France.