A BRIEF TRIP TO FRANCE

MAY 1940

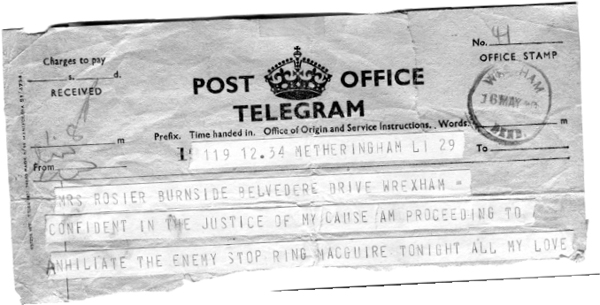

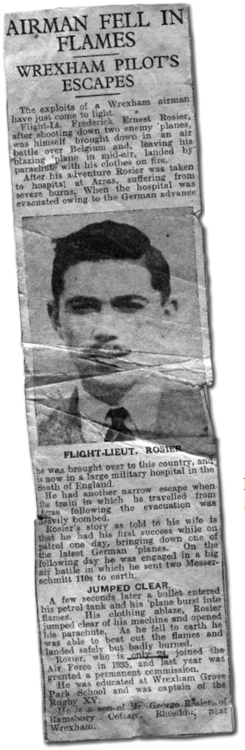

Thursday 16th May was the day when for me the war started. That morning while on early morning patrol from North Coates with part of my flight, I had been recalled to Digby, to be told that a composite flight of pilots and servicing crews was required to leave for France to reinforce 61 Wing, Air Component. Prior to leaving I sent a telegram to Het who had arrived back in Wrexham from the guesthouse in Ruskington where we had been staying for a few days.

Although impressed with my gallant words she told me later that she was worried that my determination would affect my judgement. And maybe it did as I returned from France a week later, a badly burned stretcher case.

At 2.00 p.m. that afternoon six of us from 229 Squadron left Digby and landed at Manston to refuel. In addition to me they were Pilot Officers Bussey, Gower (I think), Dillon and Simpson and Sergeants Johns and Merryweather.

At Manston B Flight from 56 Squadron at North Weald joined us. We knew 56 very well as in those days there was a lot of social interchange between squadrons. They were led by a friend of mine, Flight Lieutenant Ian Soden. I felt very proud when told that I was to command this composite squadron.

While waiting to be refuelled at Manston I wrote to Het:

My Darling Het, I have only a few moments to spare before we go off on our big adventure. I’m afraid I can’t tell you the name of the place but it is in the North East near Arras. It came rather as a shock this morning. Poor Mac is very crestfallen. Well my darling wife, keep your chin up – they might let me come home on leave soon. Mac is packing up my kit and it will be stored at the Padre’s house. My car will also be there. Tell Dad where I’m off to and tell him I had no time to write. All the love in the world my darling, darling wife. I love you so much.

Fred.

Early that evening we left for France and rendezvoused with a Blenheim which led us to Vitry-en-Artois, near Douai. The aerodrome was a large field with very long grass. There were no obstructions except a crashed Blenheim in the middle.

Landing at Vitry in L2142 at about 6.30 p.m. we were taxiing to dispersal positions when a car speeded up and a wing commander jumped out. Finding out that I was the leader he asked whether we had any fuel left. When I confirmed that we had, he, rather shakily I thought, burst out with, "For Christ’s sake keep your engines on and stand by to scramble. There are sixty-plus bandits approaching." I did what I was told.

However, it was not long before our engines started overheating. I told Soden’s flight to switch off. Still nothing happened, until one of my pilots, whom I had sent to find out the form, returned saying that the airfield was deserted. We immediately switched off and walked down to the local village where we found the wing headquarters’ mess in the only hotel. The wing commander who had given the order to stand by was there. Such was the state of confusion and panic that when I complained about our treatment he said he was frightfully sorry but the events over the last few days had been so tremendously hectic that he was tired out and he had forgotten all about us. I was pretty angry as you can imagine. It was obvious that the events of the previous few days had affected him so much that he was in no fit state to do his job. Two days later he was invalided home with a nervous breakdown.

On asking him where my pilots’ accommodation was he told me that we must find our own. Two pilots, who I then sent to find us billets in local houses, returned saying that no-one would have us. Clearly the locals were terrified that the Germans would arrive soon and punish them for looking after British airmen. I told them to try again, this time brandishing their revolvers. The ploy worked and we got to bed at about 11.00 p.m.

The next morning we were up before dawn and at 5.00 a.m., I made the first of five sorties that day leading a flight of six Hurricanes from 229/56 Squadron on a patrol towards Brussels. The sun was well up by then but it was still cold. No enemy aircraft were sighted, but east of Lille we ran into a barrage of AA fire. However, no-one suffered a direct hit and we all returned safely.

At 9.30 a.m. four Hurricanes of 229/56 scrambled in pursuit of raiders who had dropped bombs on Vitry. One of these was shot down by Ian Soden. At 10.30 the alarm sounded again and I scrambled with some of B Flight but returned half an hour later not having seen any raiders.

That afternoon a Dornier appeared over the airfield flying high and out of the sun. It dropped a large bomb on the airfield but did not cause any damage. As it made its second run it was intercepted and shot down by one of the three Hurricanes that had been at readiness and had scrambled.

There was no further activity of note that day but we did not leave the airfield for our billets in Vitry until half an hour after dark, by which time we were very tired and hungry.

The next morning, 18th May, we were again at the airfield by 4.30 a.m. My first action of the day was at 10.45 when I led a patrol of six Hurricanes, three from 229 Squadron and three from 56 Squadron, with orders to patrol between Brussels and Antwerp. Fifteen minutes into the flight we sighted some forty Me 109s at about 8,000 feet. I ordered all the Hurricanes to attack and singled out an enemy aircraft, fired and destroyed it. I then fired my remaining ammunition into another enemy aircraft but did not see it go down. Out of ammunition and with my instrument panel hit by some German bullets, I broke off the engagement and landed at an airfield near Lille where I refuelled.

What I saw there made me livid with rage. Sitting on the ground there were rows upon rows of brand new US fighters, but the French air force had decided not to fly them, nor to participate in the battle. The whole thing was a shambles.

The other two 229 Squadron Hurricanes were shot down in the battle. Pilot Officer Desmond Gower baled out and returned safely to Vitry on foot but Pilot Officer Michael Bussey was taken prisoner when his aircraft crash-landed. Having refuelled, I flew back to Vitry. Having returned to England Gower was to be shot down and killed on 21st May.

That afternoon, with only three aircraft serviceable, as we were in the midst of re-arming and refuelling prior to escorting some Blenheim bombers tasked with destroying the Albert bridges near Maastricht, fifty-plus Me 109s appeared out of the cloud over the airfield. We scrambled and they clearly had us at a great disadvantage and tried to pick us off as we were taking off. It was at this moment that Pilot Officer Dillon was shot down and killed. Somehow I managed to take off, get my wheels up and gain some height. I was at about 4,000 feet on the tail of an Me 109 when my Hurricane’s fuel tank was hit by cannon fire from another enemy aircraft that I had not seen behind me. I was soon in a terrifying situation. My plane was on fire with burning fuel coming into the cockpit and my flying suit was in flames. I tried to open the hood to bale out but in spite of pushing with all my strength it was jammed and I could move it only four 01־ five inches. I was trapped and I remember sinking back into my seat and thinking ‘well that’s that’. The pain was almost unbearable. The next thing I remember I was falling through the air. The aircraft must have exploded. Instinctively I pulled the ‘D’ ring and my parachute opened. A minute 01־ so later I landed near the aerodrome at Vitry with my clothes on fire. I tried to put the flames out with my hands and remember how surprised I was when my skin began to come away.

Ten years later a friend of mine Teddy Donaldson who was commanding 151 Squadron at Vitry told me that he had saved my life by stopping some Frenchmen taking pot shots at me whilst I was coming down by parachute.

I must have passed out for the next thing I remember was waking up on the ground and being put on a motor cycle by a French civilian and taken to the field dressing station in Vitry.2 That evening the British Army headquarters at Arras and the hospital were evacuated. Arras was left to the advancing Germans. Therefore, unbeknownst to me at the time, I was put in an ambulance and transported to Frévent where the army had established a hospital in a large chateau. Apparently the journey took seven hours as the roads were covered with army vehicles and the cars and carts of refugees who had already begun their trek westwards. 229 Squadron Operations Record Book states on 19th May Pilot Officer Simpson arrived back from France and Belgium. Simpson reported that I was shot down in flames and later was admitted to hospital seriously burned. He also stated that I was believed to have shot down two enemy aircraft.

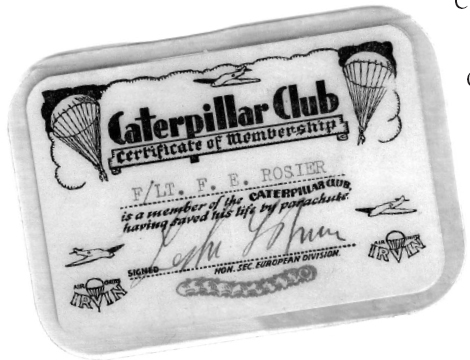

When I woke up at Frévent I found another pilot, a friend of mine from 56 Squadron, Barry Sutton, was in the next bed suffering from a bullet wound in the foot sustained during the same battle. He had travelled in the same ambulance as me. In his book The Way of a Pilot Barry describes how my neck, face, legs and lower arms were covered with a black coating of tannic acid. My hands were the worst burned part and I held them above my head to keep the blood out of them. The pain was intense and Barry thought I was going to die. Fortunately, he was wrong. The gods were on my side. I survived and I thus became a member of the Caterpillar Club, membership of which was exclusive to those whose lives had been saved by a parachute.

The next morning we were moved again. In addition to Barry, two wounded army officers joined us in the ambulance. One was a young second lieutenant, who turned out to be the son of General Sir Alan Brooke, chief of the imperial general staff for most of the war. After another long journey (the thirty miles on roads cluttered with refugees took four and a half painful hours) we reached Le Tréport, a large military hospital under canvas where we were cared for by Sister Gutteridge, of the Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps who hailed from Yorkshire. Kind and brave, I straightaway christened her ‘Sweetie-Pie’.

It was to Sweetie-Pie that I dictated a letter to Het on 19th May as follows:

My dear Het

You will no doubt be very surprised to hear that I am now in a military hospital in France. On Saturday afternoon I received a shot in my petrol tank and my machine caught fire. Luckily I got away by parachute. I am suffering very slightly from burns. There is a possibility that I shall be sent to England to recuperate. My hands are bandaged and I am unable to write myself.

Love and I hope to write myself in a day or two.

Fred.

After two days in Le Tréport, on Wednesday 22nd May, in the face of the German advance, we were again evacuated by ambulance and headed for Dieppe. On the way, I was told later, our convoy, despite the proliferation of red crosses, sustained heavy casualties from repeated attacks by Me 109s. I had no knowledge of the attacks as I was unconscious most of the time. We eventually arrived at Dieppe. There, as the hospital ship the Maid of Kent had been bombed while waiting in the harbour, we were put on an ambulance train heading for Brest where the harbour turned out to be mined anyway.

Again, despite its red crosses, the hospital train was dive-bombed and machine-gunned. After a journey that seemed interminably long, we eventually arrived at Cherbourg early on the Friday morning of the 24th of May. Throughout the journey I had been unable to see as my eyes had swollen shut. In addition to tending to my very painful and pretty severe burns, Sweetie-Pie held cigarettes to my lips and fed me with a rough French wine – Pinot. What an excellent compassionate nurse she was. When we eventually reached Cherbourg we were put on board a hospital ship where we waited for darkness to make the crossing to England. Regrettably, Second Lieutenant Brooke (or the colonel as we had christened him) had to be left behind when he was assessed as too ill to travel any further. I later learned that he had died in Cherbourg.

When we reached Southampton we were off-loaded and despatched to Queen Victoria’s Naval Hospital at Netley on Southampton Water.

Het received a telegram from Sweetie-Pie, who had left us at Southampton, and was soon on her way by train from Wrexham. She stopped the night at the Paddington Hotel and came on to Netley the next morning. Already worried about what state she would find me in, she was further disturbed by the fact that she was not allowed to go to my private ward until the matron was free to accompany her. Then came another blow for Het, and for me. Outside the door I heard the matron saying, "Don’t express surprise at his looks" – or words to that effect – "we are afraid that he has lost his sight". Het came in clearly delighted that I was safe, heard parts of my story, and drank the dregs of the wine while trying to control her emotions. Nothing was said about my sight.

Years later she told me how horrified she was at my appearance. It was early days for the treatment of burns. I was being treated with gentian violet and tannic, something which she said made me resemble a rhinoceros. My eyes apparently were just slits of yellow ‘matter’. Forty years later she could still remember the acrid smell which was about me for some time.

From the hotel in Southampton where she was staying Het rang up the CO of 229 Squadron, at Digby, to give him a message from me about the German tactics and how I thought we could counter them. I had learned in two days that much of our pre-war exercise training was useless in practice against this enemy. These tactics were based on the assumption that we would be fighting enemy bombers and not fighters. Our Hurricanes had no rear armour, our guns were harmonised at the 400 yard ‘Dowding Spread’ rather than the more effective 200 yards, and we still flew in tight Vic formations, which made us vulnerable to enemy fighters, rather than in pairs or fours . We also used the outdated attack system laid down by the Air Ministry Manual of Fighter Tactics (1938) which was useless for the type of air combat we experienced in France.

I had also learnt that in combat very few pilots, even those with the very best eyesight, had the ability to scan the sky and take in everything that was happening. These were lessons that I never forgot and continued to emphasise during the remainder of my service career.

Looking back it seemed that there was no way of stopping the Germans who had started their ‘blitzkrieg’ on 10th May. Their combination of tanks and infantry, plentiful and effective air support, allied to the brilliance of their commanders and the ‘press on’ spirit of the troops was overwhelming. In comparison the French army and most of its air force lacked the will, and the training, for the fight. I felt great pity for the refugees fleeing from the Germans. They included young and old and travelled in cars with mattresses on the roof. Some were carrying babies, some were carrying all their worldly possessions. Others, less fortunate, were pushing hand carts, wheelbarrows and a few had horses and carts. They cluttered the roads running west.

The British contingent, although small, was resolute and brave, and could not have been expected to stem or even slow down the German advance which was on a very wide front. We had no intelligence, no early warning, communications were nonexistent so we had no idea when we were going to be attacked. It was as though we were operating blind-folded.

‘OFF GAMES’ JUNE-SEPTEMBER 1940

After a week at Netley the patients were evacuated. Three of us went to the Cornelia Cottage Hospital in Poole, where we service casualties were treated as heroes. The other two were a Green Howard’s NCO who had been badly burned in Egypt before the war, and the marine officer son of Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, First Sea Lord at that time. One day Pound caused great panic by failing to return from an afternoon stroll. He was eventually found asleep on a nearby bench. His behaviour curtailed our freedom of action and alcoholic intake for a time.

Het visited me almost every weekend. She left school in Wrexham early on a Friday afternoon travelling by train as far as Woking where she stayed overnight. She avoided staying in London where we felt that bombing could start at any moment. She resumed her journey the next morning by train to Southampton and onwards to Poole where she arrived at the hospital at about 1.30 p.m. She left Poole by train for London at about 8.00 p.m. on the Sunday evening. She had supper at a cost of about 2 shillings (10 new pence) in the very popular Lyons Corner House in Piccadilly Circus, and then took the 12.10 a.m. train from Paddington arriving at Wrexham at 6.30 in the morning. There were no sleeping compartments on the train so, on my instigation, and against her better principles, she bribed the guard with half a crown to open a first class apartment for her. With little or no sleep she was off to school at 8.30 a.m.

She brought me news about my friends, about the squadron, about the outside world in general and about England during and after Dunkirk. She told me about stepping over completely exhausted Dunkirk survivors asleep on the platform at Paddington, about the newly formed WVS (Women’s Voluntary Service) manning the station platforms with food and other comforts for the returning troops. She also told me about the depressing sight she had seen at Southampton harbour of a crowded troop ship from which hundreds of Canadian soldiers were shouting to the folk on the dockside that they had been across to France that morning but had not been allowed to disembark. I guessed that this was most vital (and depressing) news. It was. Two days later Churchill announced that France had fallen.

She told me of the unpopularity of the RAF generated by those returning from Dunkirk. "Where was the bloody air force?" was their constant cry. At one station, when Het’s train drew up alongside a troop train, she startled the other occupants of her carriage by jumping up and giving the troops an answer. She told them that she couldn’t vouch for the RAF in general, but she did know where one particular pilot was. In fact she was on her way to visit him as he had been shot down and badly burned in France. She was too angry however to register their reaction.

She told me too of the 200 Dunkirk survivors with whom she had travelled on the night train to Wrexham. How, in the early morning light outside Wrexham station, they ‘fell in’ under the orders of a sergeant major. They were from about fifty different units, each with only two or three men left. She said it was a sad and depressing sight but she was heartened by the smart way they finally marched off to Wrexham barracks.

It was she who encouraged me to get better and who cheered me up.

Most nights the sister on duty, whom I liked, used to visit me for an hour before giving me my next dose of morphine. During this hour she would kindly help me to drink a glass of beer. I kept the crate under the bed. The first time I slept the whole night through was a definite sign of progress but I must admit that I was a little sorry that I had missed the beer and chat with the sister. All the time my sight was improving and I was being allowed to go out more and more and for longer periods.

We had a most lovely summer in 1940. We often sat in the hospital grounds looking down at the flying boats in Poole harbour. Sometimes we went by bus to Bournemouth. The town was crowded with a mixed bag of servicemen who had managed to make it back across the Channel. The colours of their many different uniforms were of great interest. There was a predominance of French sailors. Regrettably, some of these later chose to return to France.

When Het was with me we would have tea at The Royal Bath Hotel and sometimes a meal at Bobby’s, a large department store. There we would be entertained by a string quartet of rather drab middle-aged ladies. An incident in Bobby’s caused Het such great embarrassment that she threatened never to come out with me again unless I mended my ways. I had done the unforgivable. When a sympathetic old lady asked how I had got my burns, I had replied "smoking in bed". I can only justify such crass behaviour by the excuse that I did not like being an object of pity. I knew I was a most unappetising sight: my face was so horribly scarred that I sometimes saw people turning away in horror. Others seemed to be fascinated with my bandaged arms held almost straight out in front of me. Eating became a long and laborious process. I did not want pity – or curiosity. People actually were very kind. A doctor at the hospital invited us one weekend to stay at his home, a lovely Georgian house in Wimborne just across from the abbey. I remember the joy of his seven-year-old son when I was able to present him with a quite sizeable piece of shrapnel which, with his father’s help, had worked itself out of my leg.

When in due course I put in a claim for uniform, shoes, and a watch etc. which had been cut from me after I came down in flames, it was refused. It was pointed out that you could not have a uniform allowance twice. I was given mine when I joined up in 1935. I therefore had to buy myself a new watch upon arriving on sick leave in Wrexham. Later the cost of the service watch lost in the flames was deducted from my pay. Such was the state of the country that we ‘took it all in our stride’ with no grumbling.

One weekend after I had been in hospital for a month, Het showed me the telegram from Air Ministry stating I was missing and asking her to let them know if she should find me. I doubt she ever bothered to get in touch!

The war news was depressing. The French had surrendered, which had not surprised me; the BEF (British Expeditionary Force) under intense pressure had been forced back to Dunkirk and the beaches; and the RAF losses had been extremely heavy. Then came salvation, which was being hailed as a victory by Churchill. Ships of all sorts of shapes and sizes answered the call to brave the perils of the Channel and they, together with the navy, helped to evacuate thousands of British troops and a considerable number of French soldiers from Dunkirk. It was a brilliant operation, at first seemingly hopeless. RAF fighters, Spitfires and Hurricanes, also played their part, defending inland from Dunkirk, over the beaches and over the armada of ships. Without their support the outcome would have been very different.

In early August I was discharged from hospital and sent on a month’s sick leave to Wrexham. We chose to spend part of it staying at a pleasant country pub in Gwyddelwern, close to Corwen and the River Dee. I was just about able to hold a fishing rod and cast a line and despite my amateurism many a pleasant and productive day was spent on the banks of the river and many a pint drunk at the Red Lion. After a few days we moved on to Abersoch on the Lleyn peninsula where amongst other relaxations we were taken out mackerel fishing.

Throughout this time a great air battle was going on over southern England. I hankered for every scrap of news. Although delighted to hear that pilots were saved, I knew how vital the stock of aeroplanes was; I feared they must be rapidly running out. It was at this time, encouraged by Beaverbrook, that the British people gave up their pans and anything made of aluminium ostensibly for new fighter aircraft.

In early September, upon completion of my leave, I returned to 229 Squadron now at Wittering, which at the start of the war had become a fighter station. There were only about half a dozen of the original squadron pilots left. I had lost two of the six I had taken to France – one eighteen-year-old, Dillon, had been killed, the other Bussey, just the same age turned up months later as a prisoner of war. Whilst operating from Biggin Hill over France and the beaches, five had been killed and six shot down and wounded. One, who had been shot down three times, was returning from Dunkirk on a RN destroyer when it was sunk. He eventually reached Dover, where, to cap it all he was booed.

The station was commanded by Wing Commander Harry Broad-hurst, whom I had last seen at Vitry where I was shot down. It was he who had asked when we arrived if we had non-armour piercing tanks. When I said "No, it’s suicide," he replied, "You mean bloody murder".

The author holding daughter Lis at her christening at RAF Northolt, 5th March 1944.

Het, who became a great friend of his wife Kay, stayed sometimes at The George at Stamford and sometimes at their residence Pilsgate House, known to us all as The Pilsgate Arms. This, the Dower House of the Burleigh Estate, had been taken over from Lord Burleigh, who had been a well known Olympic hurdler. Later in 1944 Kay was godmother at our daughter Elisabeth’s christening at RAF Northolt.

During that month of September my job, such as it was, was helping out in the ops room. But I also took time off to do some flying at nearby Sutton Bridge, where my previous CO, Mac Macguire, was now chief instructor. Officially I was not fit for flying, but in early October this changed when doctors at Halton declared me able to undertake further flying duties. It was what I wanted.

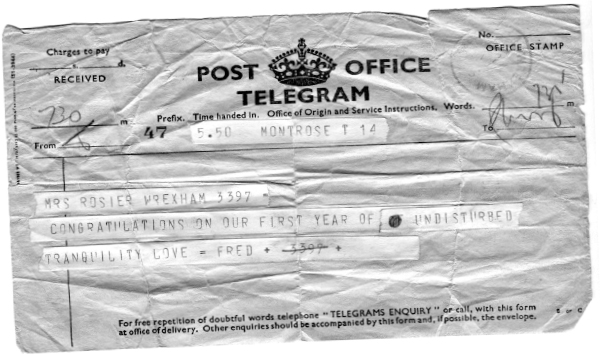

On some evenings when no enemy air activity was likely, Broady would take Pat Jameson, a New Zealander, and a very good fighter pilot, and me to our favourite pubs in the vicinity. One of these pubs was the Ramjam, north of Stamford and further up the Great North Road from Wittering, which had a very good-looking barmaid who was looked upon with favour by Pat, until his girlfriend, who had made her way from New Zealand, quickly put an end to ‘that nonsense’. Another favourite pub we called the Honky Tonk was on the crossroads where one turns left off the A1 for Peterborough, Stilton and Brampton. On our wedding anniversary 30th September, perhaps somewhat ironically, I sent Het a telegram:

On one of her frequent visits from Wrexham Het came along to a drinks party at the mess, attended by the AOC of 12 Group, Air Vice-Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, who almost a year earlier had told me that, "night-fighters were the thing". During the course of the evening the AOC asked to meet Het. Dismissing me, he apparently said to her, "What do you think of your husband flying again?" On being told, "I suppose it is up to him," he said, "I want him to go as the CO of a night-fighter squadron in a couple of weeks, but don’t you tell him, I will." Of course Het told me; I was filled with apprehension and delight.

A week later the AOC contacted me and told me what he had intended. He then went on to say that my old squadron (229), then at Northolt, had lost its CO and if I wished I could immediately go to Northolt and take it over. I jumped at the opportunity and left next day, arriving there on 16 th October.

229 SQUADRON NORTHOLT AND SPEKE OCTOBER 1940-MAY 1941

At that time Northolt, to the west of London and in AVM Keith Parks 11 Group was one of the most important fighter stations in the south east. In addition to my 229 Squadron, the Northolt wing included the Polish 303 Squadron whose CO and flight commanders were RAF and 615 Auxiliary Air Force Squadron. There was also a large transport squadron. The station commander Group Captain Vincent had been shot down and wounded a few days before my arrival and his place was filled by Wing Commander ‘Tiny’ Vasse.

My squadron of seventeen Hurricanes still had the same adjutant, Hogan, a First World War pilot who naturally was much older than me and who looked after me like a father. Sadly, there were only a very few pilots who had been with me earlier that year. These were my right hand man Flight Lieutenant Smith, Flying Officer Simpson who had been with me in France, and the loyal and stalwart sergeant pilots: Mitchell, Edghill and Johns, who were founder members of the squadron. During that period, in addition to Flying Officers Salmon, Bright and McHardy, Pilot Officers Dewar and Brown and Sergeants Hyde, Silvester and Arbuthnot, the remainder included two Rhodesians: Flight Lieutenant Finnis and Flying Officer Holderness, two young Poles: Flying Officers Stegman and Poplawski, two Belgians: Pilot Officers Ortmans and du Vivier and the New Zealander Pilot Officer Bary.

My first operational sortie back with 229 was on 19th October, exactly five months since my last sortie in France. Whilst at Northolt, we mostly operated in squadron and wing strength, the squadron commanders taking it in turns to lead the wing. Our most common task was to cover the south-eastern approaches to London by patrolling the Maidstone line at 25,000 feet at squadron or wing strength. Unfortunately, because of the height we were told to patrol at, we often found ourselves below the enemy fighters. Enemy fighter-bombers frequently jettisoned their bombs on sight of us and several of our losses occurred when chasing enemy aircraft back across the Channel.

On 26th October I wrote to Het by then back in Wrexham.

We did one patrol of one and half hours and saw several Huns, but could not make contact as they were going back across the Channel. My goodness it was cold up at 27,000 feet. The visibility was amazing, probably over 100 miles and a great part of the French coast was visible.

It was on that patrol Flying Officer Simpson was killed when he was shot down by a Bf 109 off the French coast.

It was the practice to detail two pilots per squadron to weave behind the formation, their job being to warn of attack from the rear. It was a foolish practice that detracted from operational efficiency because it reduced the speed and rate of climb of the main force. Furthermore, the two unfortunate pilots designated for this task were often the least experienced and the most likely to be shot down. Accordingly at Northolt we fitted rearward-view mirrors to the top of the windscreens of our Hurricanes.

The squadrons took it in turns to disperse for the night on an airfield a few miles away at Heston, which after the war became Heathrow. Whilst there the pilots retired to the Berkeley Arms on the Bath Road for drinks and dinner which we finished invariably with port, courtesy of the manager. Het and I stayed with some very kind people at The Hall in Hanwell, from where we could hear the sounds of the bombing of London. They were paid four shillings a night for billeting us. We have been back there since and in place of The Hall and its grounds is a large housing estate.

At the dispersal airfield early one misty morning that autumn we started our engines and began to take off as a squadron to return to Northolt. About halfway through our take-off run I was horrified to see another squadron coming straight at us. Avoiding action was impossible; but by a miracle there were no collisions. The other squadron, Polish 303, had used a different radio frequency from us and consequently we had no warning of their take-off.

I noted in my log book that on 14th November we had an active day when on three occasions the squadron met formations of Bf 109s scoring three ‘probables’. The AOC of 11 Group was keen to take action against the night-bombing raids on London and I spent many nights on patrol. And on 16th November noted that, having taken off at 3.15 a.m., ‘on landing my port oleo leg collapsed causing damage to the aircraft’. On one of these patrols Pilot Officer Ortmans’ aircraft P3039 was damaged beyond repair in combat.

On another occasion I took off in my Hurricane P3212 one moonlit night hoping that I would intercept and shoot down one of the many German aircraft dropping bombs in the vicinity; but had no luck. To return to Northolt I lost height between two clutches of barrage balloons, found Western Avenue and then requested that the runway lights be lit for my landing. The controller refused because the enemy bombers were still active. I had to come in and land without lights, damaging the undercarriage in the process. The next morning the controller responsible was dealt with severely and an order went out to the effect that the safety of our own aircraft was always to come first whatever the risks involved. Two days after my arrival on 18th October, 303 lost four pilots when a patrol returning to Northolt became lost in deteriorating weather.

One morning the dreaded phone rang but it was not the usual order to ‘scramble’, but Tiny Vasse asking me to go along to his office. He told me that during the night a Polish officer had smuggled a woman into his room in the officers’ mess. At about 3.00 a.m. the bell had rung so persistently in the batman’s room that he eventually got up. Knocking on the door of the Pole’s room, he was told to "come in". There he was presented with the sight of a naked Pole and a half-naked woman, with the Pole saying, "We would like breakfast for two". The batman, most affronted, reported the incident. In answer to Tiny Vasse’s question as to what course of action I would take, I suggested he send for the senior Polish officer on the station, tell him the story and ask him what he was going to do about it.

The senior Pole duly arrived and in answer to Tiny Vasse’s question, said without any hesitation, "It is easy, we will shoot him." Vasse, taken aback, leapt from his chair and in no uncertain terms told the Pole that he was in England now, not in Poland. The upshot was that the amorous Pole was confined to camp for a couple of weeks.

During my time at Northolt we had few victories for at the end of October the Luftwaffe gave up their daytime massed-bomber attacks, resorting to wide-ranging attacks by small numbers or even single Me 109s carrying bombs. Their time spent over this country was very brief; they were fast and they proved difficult to intercept. However, during this period 229 had come together as a squadron and morale was high.

On 15th December the squadron left Northolt and returned to Wittering. After a week at Wittering we were posted to Speke, near Liverpool, ostensibly for a rest. On 21st December I flew up to Speke on a recce and the next day the squadron, with its eighteen Hurricanes, arrived two days before Christmas. I was glad to be posted to Speke which was close to Het’s and my homes in Wrexham.

Initially there was little activity by day but the heavy bombing of Liverpool by night started in early January.

Having arrived at Speke we concentrated on operational training with our loyal and hard working ground crews: the fitters, the wireless men and the armourers. On one occasion I led a squadron formation over Wrexham with two aircraft weaving about behind the formation. Seeing this, a friend of Het’s said to her, "I know it is none of my business but tell Fred that two of his pilots were fooling about at the back!"

Het and I had a pretty thatched house, Bromley Hatch, in the village of Hale, close to Speke. Our neighbour, a Liverpool butcher, was generous and the local pub, The Childe of Hale, was pleasant. Our relationship with the station commander, Group Captain Seaton Broughall (and his girlfriend Poppy) was close and we were not troubled by the other squadron, 312 Czech Squadron, whose officers rarely used the mess. I was given a car, hired locally, but soon damaged it driving as we did with hooded lights. The second sustained similar damage, and when it came to the third, I was warned it would be the last one.

But life at Speke was not the rest we had been promised. Liverpool and its outlying districts came under some heavy night attacks by bombers, and the city suffered. Het spent those nights in a ‘command’ air raid shelter at Speke, a wise precaution because our house was not far from a Q site, those designed to attract the attention of the bomber crews away from the main target.

When warning of the night raids was received I, usually accompanied by my stalwart sergeant pilots, flew to RAF Squires Gate near Blackpool or RAF Valley in Anglesey. There we awaited the order to scramble and to be directed into the bomber stream. On a few occasions I sighted bombers but by the time I turned to attack I had lost them. We had no radar and relied completely on eyesight. It was most frustrating. To keep up the morale of the heavily bombed Liverpudlians we used to fly around the city just as dusk was falling. One afternoon when Het was at the hairdressers in Liverpool she reported that people had rushed to the windows to see me and my chaps circling the city. They were most heartened thinking they would have protection that night. Little did they know that when we landed they were on their own.

At Speke I lost three valued pilots. The first, Sergeant Arbuthnot, crashed in the Mersey whilst returning to the airfield in thick mist. The other two, Pilot Officers Dewar and du Vivier, were mysteriously lost over the Irish Sea on 30th March. We came to the conclusion that they had collided when being vectored towards a German reconnaissance Ju 88 or Do 17. They were a great loss.

Early in the war I had agreed with Mac Macguire, the CO of 229, that air crew should only be recommended for decorations such as the DFC and DFM if they had performed over and above the normal line of duty. We agreed that the normal line of duty included shooting down one, two or three aircraft depending on the circumstances. That was our job.

As a result by the beginning of 1941 no one in the squadron had been decorated – something that was matched by no other squadron. The point was driven home to me one evening in March 1941 when the three brave sergeant pilots came to my house by arrangement. They had complaints and over a glass of beer I told them to air them freely. The first was that many sergeant pilots junior to them and with less experience had been commissioned. The second one covered the absence of decorations in the squadron. I listened and I realised that I should change my policy. Het too had been pointing out how much such decorations meant to wives, mothers and the general public.

Though I regarded those sergeants as the lynch pin of the squadron, it had simply never occurred to me to recommend them for commissioning – or for a medal. They forgave me for my lack of thought. They and their wives subsequently became great friends of ours for the rest of their lives.

The next morning I recommended the three for immediate commissions. These were celebrated by a squadron pilot’s party at our house, where the new officers arrived in borrowed uniforms. When we arrived late – having been elsewhere and given the key to one of the flight commanders, the party was in full swing. The centrepiece was a goat, which should have been cropping our large lawn. They were given a great and well-deserved promotion party. Johns eventually became a group captain, Mitchell a wing commander and Edghill, who was the first in the squadron to get a DFC whilst serving in the Western Desert, retired on medical grounds, as a flight lieutenant.

This kind of life away from the main operational areas could not go on for ever. Therefore, sometime in March I was not surprised to be told the squadron was to move. However, I was surprised when I was told that we were destined for the Middle East, most likely for the Western Desert.

During the next few weeks preparations for the move went ahead. The ground crews were to embark on SS Strathmore in Liverpool and were destined for a long sea voyage taking the comparatively safe route round the Cape of Good Hope and up to East Africa and thence to Egypt. The pilots were to ‘endure’ life on an aircraft carrier from the Clyde to the Mediterranean where, at some point, we would fly our Hurricanes off the carrier to Malta and then on to Egypt. Four of my pilots were to take a different route by ship to Takoradi on the Gold Coast in West Africa and then would fly their Hurricanes across Africa to Egypt.

Soon the time came for the farewell parties and a tearful goodbye to Het – and then on 10th May we were off, I by train to the Clyde, and she by service car to Wrexham as ‘officer’s baggage’.

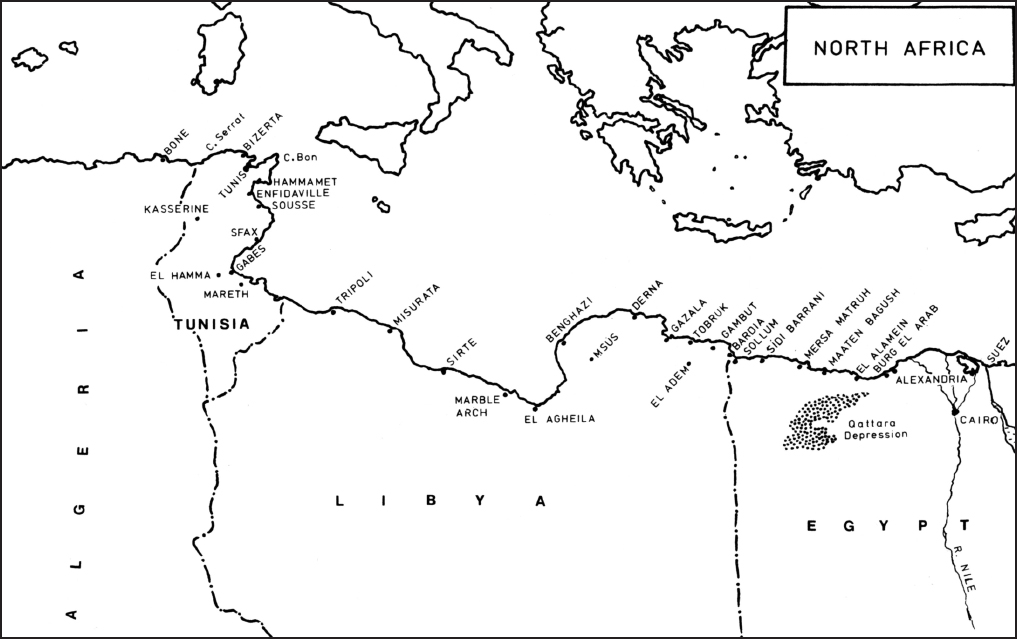

An overview of North Africa