SAND IN MY SHOES

A MEDITERRANEAN CRUISE

On boarding HMS Furious at Greenock on the Clyde, I immediately discovered that two old friends were on board, Derek Eyres, then of the Fleet Air Arm, formerly of my flight in 43 Squadron and Squadron Leader Macdonald (Cousin Mac) the CO of 213 Squadron which, along with 249 Squadron, was also on board. That evening we three were enjoying a drink with a friend of Eyres, the captain of a destroyer which had just returned from the successful Lofoten Islands raid, when we were ordered to return immediately to the Furious. A drink or two later came the news that the ship was getting underway. By the time we reached her, she was actually moving. We were then faced with a long and somewhat ignominious climb up rope ladders to the flight deck where we were piped aboard, much to the amusement of our pilots and many of the ship’s company.

During the voyage to Gibraltar we RAF officers were asked to limit our drinking as there was concern that the gin would run out. In a letter I wrote to Het while on board I said, ‘Eyres has a violin which I have played so much (Gin only being 2d per tot) that my fingers are blistered’.

Soon after our arrival at Gibraltar on 18th May the Furious, together with other carriers and warships, was diverted to join the hunt for the German battleship Bismarck. Before the Furious departed on this mission on 21st May, six pilots each from 229 and 213 Squadron were dispatched from the carrier for Malta and Egypt. There they were attached to 274 Squadron and assisted in covering the evacuation of Crete.

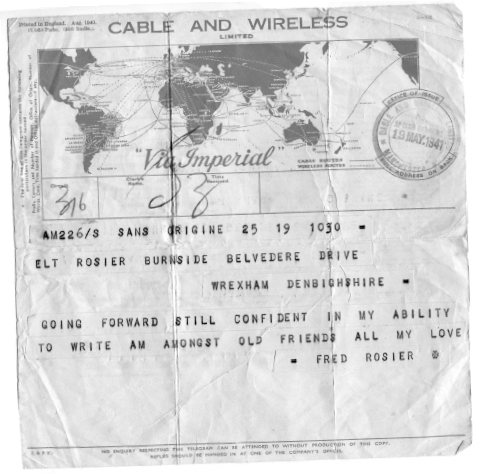

The remainder of us were left behind to enjoy over two weeks of enforced holiday staying in luxury ‘in a minor suite’ at the Rock Hotel. We were invited to parties every night. One that still remains in my memory was given by the ‘Gibraltar Millionaires’ for Her Majesty’s Forces. There was no blackout at night and food rationing was forgotten. We ate our fill of deliciously prepared food, much of which we had not seen for well over a year. In a letter to Het I told her, ‘I had the best sole I have ever tasted with half a lemon, and then a Spanish omelette’. From Gibraltar on 19th May I sent a telegram to Het:

29th May I again wrote to Het, ‘I bought half a dozen pairs of silk stockings yesterday, they cost thirty-six shillings altogether, so apart from the fact they are scarce in England they are much cheaper. I made a guess at the size of your feet and legs darling’. I also sent her a bottle of scent.

When the Bismarck had been sunk, a slightly depleted convoy – HMS Hood had not survived the battle – returned to Gibraltar. On her arrival on 5th June, we rejoined the Furious, and, as we left Gibraltar, the two squadron commanders were summoned to a briefing by an admiral who gave us our timings for take-off from the carrier to Malta. We were told that for safety reasons (the safety of the carrier, not ours!) we were to take off in the dark. As not one of us had ever taken off from a carrier, let alone in the dark, this was fraught with danger. We argued against the operational sense of this and during our remonstrations we pointed out that the main object of this exercise was to get us safely to Malta.

Finally, both of us said that we, as individuals, would obey the orders but would not order our squadron pilots to do so. Eventually, the admiral backed down. It was agreed that we should all take off at first light. In the early hours of the following morning, in the middle of the Mediterranean, I climbed into my Hurricane, which was positioned in front of the others and, as dawn broke, saw what a short take-off run I would have. I was sceptical about my ability to get airborne in that distance but the navy were correct in their calculations and I took off safely ahead of twelve aircraft from 229 Squadron. When we were all off the carrier we formed up behind a Fairey Fulmar which was to lead us on the 450-mile journey to Malta.

The last thing we wanted on this two and a half hour flight, which took us close to enemy air bases in North Africa, was to be intercepted. Any fighting en-route would have reduced our chances of getting to Malta because the long-range fuel tanks we needed for the flight had been installed at the expense of fifty per cent of our fire power. The emphasis, therefore, was on accurate navigation and complete radio silence with the Fulmar. It was a long, nerve-wracking flight and I think now that the radio silence was over-emphasised. However, we arrived safely – the first squadron to do so without a casualty.

After our arrival in Malta, I was invited to have dinner with the AOC, Air Vice-Marshal Sir Hugh Pughe Lloyd. During dinner he insisted that the squadron should remain in Malta under his command. I managed to persuade him otherwise by telling him that it would not be in his interests as my best pilots had not come with me but had gone via Takoradi, and he eventually agreed that we could leave. After a day’s rest in Malta we took off for an uneventful four-hour flight to Mersa Matruh on the Egyptian coast where we refuelled and flew on to Abu Sueir, some ten miles west of Ismailia. The squadron arrived without loss in Egypt on 8th June where I found the RAF was being criticised by the other services for lack of support in Greece and Crete. I am told that it was the same after Dunkirk, but at that time I was in hospital.

THE WESTERN DESERT 229 SQUADRON JUNE-OCTOBER 1941

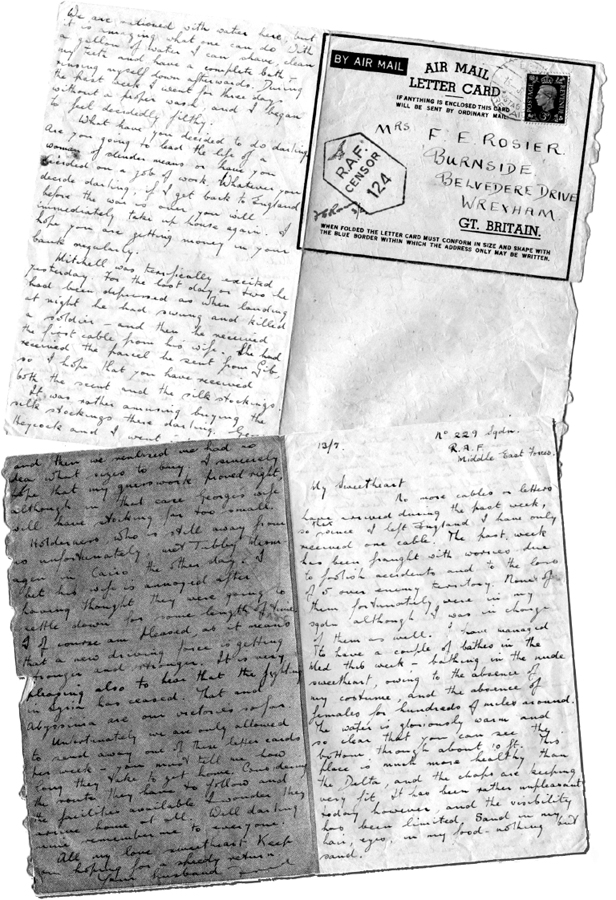

My first few weeks in Egypt were frustrating. As the squadron ground crews were still on their way via the Cape, my pilots were sent to reinforce other squadrons in Palestine and the Western Desert. A Flight was initially attached to 274 Squadron covering the withdrawal from Crete and then to 73 Squadron at Sidi Haneish where they operated as C Flight. B Flight were split between 6, 208 and 213 Squadrons. I was therefore left behind kicking my heels at Abu Sueir in the Canal Zone, the home of 102 Maintenance Unit. I wrote in a letter to Het on 17th June, ‘I am depressed darling as I am on my own doing nothing and the rest are more or less split up for the time being. Unfortunately one of the sergeants is missing.’

19th June

Darling, Smithie has just arrived here with good news. His fight’s score is four-nil, Edghill having accounted for two. I returned to Sidi Haneish and spent forty-eight hours in the desert with Smithie, Ruffhead & Co. It must be difficult for you to realise what the place is like – just miles and miles of nothing but sand – no vegetation – and to the north the terrific blue of the Mediterranean.

29th June

I am still looking forward to the time when I receive some letters or cables from you – it seems such a long time with no news. All the other chaps are in the same boat...Havejust heard that Sowrey has departed to a better land and am cast down about it. Having no control over the chaps’ movements and actions is not likely to improve my present temper, still, I have tried my damnedest and am still trying.

Increasingly bored and with the boldness and confidence of youth, I went to headquarters of Middle East Command in Cairo where I asked for an interview with Commander-in-Chief Air Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder. To my surprise, he agreed to see me and I immediately raised the subject of my lack of employment and my dispersed pilots. I told him that in my view it was a silly way to run an air force. For the past nine months I had been training up my squadron to fight as a cohesive unit and had developed a marvellous esprit de corps only to find that on our arrival in Egypt my pilots had been sent off to join other squadrons. He not only listened but agreed with my point and, within a few days, at the beginning of July, I left for Sidi Haneish, a landing ground near Mersa Matruh, 300 miles west of Cairo.

Sir Arthur Tedder, was a remarkable man; one of the best senior officers we had in the war. He could be cynical, but had a ready smile and a great gift for putting his juniors at ease. I got to know him well during his overnight visits to the Desert Air Force HQ where Air Vice-Marshal Coningham (nicknamed ‘Maori’ then changed to ‘Mary’), the AOC, would often invite some of us to meet him and have a drink.

At Sidi Haneish, in addition to getting 229 back, following the arrival of the pilots who had come via Takoradi, I was also given temporary command of 73 Squadron to which some of my pilots had been attached. 73 Squadron had not long come out of Tobruk and their CO Pete Wykeham had been sent to the Delta for a rest.

7th July

It is much cooler up here than it is down south but we are surrounded with miles and miles of desert on three sides and the blue of the Med on the north.

All I live for I’m afraid is to receive my first letter from you.

13 th July

The past week has been fraught with worries due to foolish accidents and to the loss of five over enemy territory. None of these fortunately were in my squadron although I was in charge of them as well.

After initial success against the Italians in Cyrenaica in late l940 and early 1941, the situation in the desert had undergone a dramatic change with the arrival of the Germans in the theatre. Rommel’s offensive in April 1941 had resulted in our withdrawal to the Egypt/Libya border and Tobruk became a besieged fortress. Operation Battleaxe which began on 14th June, the aim of which had been to push back Rommel’s forces and to relieve Tobruk, had failed and the situation was stalemate.

During the next few months whilst there was a lull in the ground fighting and preparations went ahead for the next offensive, our fighter squadrons which by then included 229, were continually engaged in air defence, including night patrols over Mersa Matruh, offensive sweeps and the much disliked job of escorting ‘A’ lighters to Tobruk where they docked after dark and left before dawn.

The task of defending these slow moving vessels, particularly in the late afternoon, when they were close to the main German landing grounds (LGs) at Gambut was not one we relished. The prospect of Stukas with fighter cover appearing without warning out of the red ball of the setting sun was distinctly unpleasant. On one such patrol I nearly ‘bought it’ as we used to say. I was firing at a low flying Stuka, perhaps at 100 feet, over the sea when my Hurricane suddenly went into a violent roll to the right. For a moment I thought we would crash into the sea. Fortunately I was able to regain control and by keeping the speed low and using harsh rudder and aileron control I was able to limp back to our advanced base at Sidi Barrani where I discovered that a large piece of metal skin had come adrift from the starboard wing and hit the tailplane.

Later that evening I had a call from Air Commodore Collishaw, the commander of 204 Group (shortly to become Air HQ Western Desert) and was able to tell him that the squadron had shot down six or seven enemy fighters, of which Edghill had shot down three. ‘Collie’, a Canadian ace in the First World War, had initially done well against the Italians but when the Germans arrived he was soon out of his depth. His efforts to thwart them were amateur in the extreme and he lacked the professionalism needed for the task.

Life in the desert was tough and demanding. Apart from the stress of continually being on operations, we had to put up with extremes of heat during the day and in the winter months, extreme cold at night. There were also the discomforts of sandstorms, when visibility fell to a few yards and sand got into the food and water. The flies, the shortage of water and the monotony of the daily diet of hard biscuits, bully beef, occasionally tinned fish, tinned bacon and marmalade, only enlivened sometimes by tins of Maconochies ‘M & V’, tinned meat and vegetables. But there were compensations: the vastness and the beauty of the desert, the night sky full of stars, the sunrises, and the silence. During the first few months, until it was lost, I had a violin and in the late evenings, when in the mood, I would scrape away under the night sky and the sound would come back to me, transformed. However, at Sidi Haneish where we bathed in the warm Mediterranean and had parties with the other squadrons, living conditions were more bearable.

16th July

In a way I am enjoying life up here darling, I am especially struck by the terrific camaraderie amongst the pilots, I suppose it is a natural consequence of being isolated from civilisation. The mess consists of a shack with a wooden partition across the centre. On one side we have a miniature bar, some camp chairs and a wireless set, and on the other, our so-called dining room. The food quite naturally lacks variety, but one develops such a terrific appetite that any food tastes good. We had a most successful fracas with the common horde yesterday evening and the resulting score was certainly seven to their two, probably nine to two. We have not seen Lauder since the game. Smithie, Edghill and Johns distinguished themselves, but your amazing husband met with a slight reverse right at the beginning, which necessitated his limping back to base.

On 27th July I wrote to Het: ‘We are having a very slack time of it today and I have sent some of the chaps to Alex so that they can have a night out. Most of the others are out bathing this afternoon.’ I mentioned in a letter on 2nd August that I had not yet received a letter from Het but finally received a second cable that day.

6th August

My time has been occupied during the last few days writing letters of condolence to relatives of chaps who are either missing or have been killed. It is a shocking job. At the moment I have about ten of these on the go.

There was always plenty of work to do. I often flew at night hoping to intercept the odd German bombing Mersa Matruh. On the night of 7th/8th August on one such patrol at 3.25 a.m., I shot down a Blenheim of 113 Squadron. It had just dropped its bombs on Mersa Matruh and was illuminated by search lights, when, as it did not show IFF (identification, friend or foe), I shot at it from fairly long range. Fortunately, the crew managed to bale out and were found in hiding the next day. I wrote to Het about this incident: ‘I also achieved a bitter success. I shot an aircraft down in flames but the aircraft should never have been there. Luckily the pilot was rescued. You can probably guess what happened.’

In the subsequent Court of Inquiry the senior air staff officer ‘SASO’, of the Desert Air Force Group, Group Captain Freddie Guest found the crew guilty of a ‘gross error of navigation’ but he also attached some blame to me for the shooting down. I was certain he had never been placed in a similar situation.

8th August

Nothing exciting happened yesterday darling, but this morning another game took place and we wounded a couple of players on the opposite side. I was a non player however as I had been night-flying until an early hour this morning.

On 27th August having received my first letter from Het since leaving England in May – a batch of four letters with photographs – I wrote:

Mitchell, Ruffhead and Russell are spending a few days in Alex and the rest are still up in the desert. I am trying to organise things at my base landing ground so that very soon we will all be together again. Horniman is missing after a brush with the Huns last week – so now I am rather depleted having very few of the originals left.

The 73/229 partnership, which had been a very happy one, came to an end on 27th August. 229 Squadron, again complete with the ground crews who had come via the Cape, again began to operate as an independent squadron. 73 went back to the Delta for a rest. At a party to celebrate this where we all got ‘rather merry’ their CO, Squadron Leader Peter Wykeham, recently returned from a well-earned rest, presented me with a silver tankard inscribed ‘from the CO and officers of 73(F) Squadron in memory of 73/229 June-August 1941’. I still have this tankard and it has quite a story to tell!

2nd September

I am writing at my base whilst the others are finishing their lunch. I then have to fly back to our operational aerodrome. I have been at sixes and sevens trying to get night-flying organised. We started it last night – pretty unsuccessfully as Penny damaged his A/C when landing.

There are two small oases near our base – plentifully provided with figs, dates, wild tomatoes and prickly pears. The pears grow on a kind of cactus tree and taste something like a pomegranate. The figs are ripe, but the dates are green.

On 13th September 229 Squadron pilots left for Cairo en-route to Takoradi to collect Hurricane MkIIs.

24th September

It has been completely impossible to write as since my last letter there have been great changes; first we moved to about three different landing grounds within just over a week. I then arranged for the pilots to go and collect their own aircraft [Hurricane IIs from Takoradi] which meant a trip of several thousand miles, and then I was posted to 204 Group to become fighter liaison officer. It means that I shall be promoted (to wing commander) and within a month or so will probably control at least four squadrons. Naturally I feel sad at leaving the squadron but I had a pre-sentiment that I was about to go up in the world.

So in late September I left 229 for Maaten Bagush, on posting to HQ 204 Group, shortly to become Air HQ Western Desert, where Air Vice-Marshal Coningham had just taken over as AOC. I was very sad to leave for, apart from spending a few months in hospital and in convalescence, I had been in the squadron continuously from October 1939 when it was formed at Digby, as a flight commander and then CO. Bill Smith, my senior flight commander since our days at Speke, took over from me as CO a day or two before the squadron’s second birthday celebrations, with Johns and Mitchell as the flight commanders.

STEALING A STUKA 262 WING AND OPERATION CRUSADER

One evening a few days after my arrival, Wing Commander Al Bowman, the chief training officer of the Western Desert Air Force, and I discussed the possibility of finding and flying back a Stuka dive-bomber. A number had reportedly forced-landed due to fuel shortage in the forward area close to ‘the wire’. The next day we put our proposal to the AOC Air Vice-Marshal Arthur Coningham. To our delight he agreed.

The next morning Bowman, who was a big, bluff and determined Australian, and I took off in a Wapiti with a captured Italian Stuka pilot, hoping that he would be of some help.

The Stuka. September 1941.

By midday we had reached Thalatta where we found a Ju 87 which had crashed on landing and flipped on its back. Continuing the search we flew to Al Hamra, twenty-five miles away where we made contact with a South African armoured car unit. As they had seen nothing we decided to fly further west towards enemy territory and landed at Fort Maddalena on the Libyan frontier where the 11th Hussars were based.

At this stage as dusk was approaching, because our aircraft was making us vulnerable to enemy air attack we we decided to send it back, with to his delight, the Italian prisoner on board.

That night we dined with the 11th Hussars. The officers were most friendly and having heard what we intended to do entered into the spirit of the adventure with enthusiasm. At dawn next morning loaded with rations and water for three days we set out to resume the search in a couple of their trucks with an escort of an officer and several troopers. After a few hours of nothing but sand we came across a British patrol who had seen a German dive-bomber intact. It was clear from the increase in enemy aircraft activity around us that they were also seeking their lost Ju 87.

We soon found the German aircraft standing on a patch of firm sand next to which reclined a very young British Army officer who was delighted to hand over his charge to us.

By now it was late afternoon and we were anxious to get the Stuka refuelled and to fly it back whilst it was still light. We had several cans of petrol with us and whilst our army friends were pouring this in under the direction of the wing commander, I was fiddling about in the cockpit. Suddenly there was a commotion and everyone started running away. I had mistakenly pressed a switch or moved a lever which had jettisoned the bombs. Reacting to their shouts, I was out of the cockpit in a flash, but it was not long before common sense prevailed: the bombs could not have become armed in the short distance they had fallen. So back to the Stuka we went to continue the preparations, which seemed to be going well when two CR42s came over at about 5,000 feet. Convinced that we must have been spotted we decided to try to start the engine and to get away as quickly as possible. After a few attempts with the starter handle the engine fired and within a few minutes we took off and set course towards the east. The wing commander was at the controls and I was in the rear cockpit.

After some twenty minutes cruising in a north-easterly direction the engine suddenly spluttered and stopped. We were forced to land but after a little tinkering the engine came to life and we set off again. However, again we were unlucky as the hydraulic gauge burst and we had to make a forced landing in the gathering gloom. In the process we suffered a burst tyre and damaged the undercarriage in a shallow wadi. As the light was failing we decided to set up camp for the night next to the Stuka. It was only then we realised what trouble we were in as, in the excitement of getting the aircraft to start, we had left behind our rations, water reserves and maps.

That night we slept in the folds of our parachutes. At dawn, with only our water bottles and with the prospect of at least a forty-mile walk back to Sidi Barrani, we spelled out a message with stones and then set off heading north. Around midday we saw dust clouds on the horizon. Confident that this was a friendly patrol, we streamed a parachute which fortunately was seen and our walk was soon over. We were rescued by a South African officer with a long-range desert patrol. I then returned to air headquarters to await my posting order whilst Wing Commander Bowman, with a repair team, returned to the Stuka and subsequently flew it back to our lines. Sadly, Al Bowman was killed a few weeks after he returned with the Stuka. Making an approach to a remote desert landing ground in a Blenheim with Group Captain Dearlove aboard, he was shot down by our own AA in a tragic case of poor aircraft recognition.

A few days later I flew another Stuka from the same formation which had also been flown back to our lines. I was not impressed with the Stuka. It was very slow.

In early October I was delighted to be told by Air Vice-Marshal Coningham that, in order to support the army’s anticipated advance to Tripoli – Operation Crusader – a second fighter wing was to be formed (262) and that I was to be promoted to wing commander and take it over. Operating in conjunction with the senior 258 Wing which was to be commanded by a group captain, we were to be responsible for the detailed operations and control of the desert fighter force. 262 Wing consisted of six squadrons, three each of Hurricanes and Tomahawks, and was organised so that it could control the whole fighter force of twelve squadrons and both wing headquarters. In many respects the wings, which were fully mobile and self-contained, corresponded to the group control centres later in the war. As mobility and good communications were vital for effective air support the wings would be responsible for sifting requests from the army, deciding on bomb lines and on ground-to-air signals.

6th October

Mersa Matruh

I am now a wing commander and am fulfilling the functions of this position. I am starting the whole wing from scratch – a big undertaking as you will probably gather from other sources in the immediate future. The fighting 229 is only going to be one of six with Frederick as the big white chief Truly sweetheart mine, the job is terrific.

At this time in the desert we had twelve squadrons of Hurricanes and Tomahawks plus a naval squadron of Hurricanes and Grumman Martlets from the disabled carriers HMS Illustrious and Formidable. As we had numerical superiority we decided to operate over the battle area in formations of two squadrons, a total of twenty-four aircraft, which made up for the inferiority in performance of the Hurricane and Tomahawk against the Me 109F.

In late October the CO of 258 Wing ‘Bull’ Hallahan who was almost twenty years my senior, was replaced by Group Captain ‘Bing’ Cross, an old friend from Digby days.

20th October

Things seem to be freshening up out here. Hardly a day goes past without an aerial combat over the forward areas. Sandstorms are the only things which interfere. Still I hope to have my HQ in Benghazi or even Tripoli by Christmas. Group Captain Bing Cross is now my sparring partner in charge of the other fighter wing. I think we will have a pretty fine combination as I get on extraordinarily well with him. There is only one thing I am afraid of The establishment for the CO of a wing is group captain. I hope one doesn’t come along and take over from me.

On 21st October I flew back to Alex for a day and while there bought Het half a dozen pairs of silk stockings.

1st November

I would like you to visualise darling what I am doing and where I am at the moment. It is 6.15 in the evening, quite dark and I am sitting in my office – a three-ton truck. It is illuminated by a small oil lamp. I have some chairs and a table. Within two or three days I shall make this truck my complete home, have my bed in here, and rig it up with electric light. At the moment I sleep in my tent about 20 yards away.

4th November

I went to bed fairly late last night, tired out having been working continuously since early morning. The trouble was caused by the unexpected activity of the Huns last night. They’re getting quite cheeky. That coincided with the fact that when our fighters were up, thick fog developed, causing us some anxious moments.

If I can manage it I intend getting down for a swim today. I get a very good view of the sea from my tent.

In my wing I now have two wing leaders, Johnnie Loudon being one of them. [Wing Commander Pete Jeffries was the other.]

On 14th November, in preparation for Operation Crusader, our squadrons moved to our forward battle airfields (LG110 and 111) about forty-five miles south of Sidi Barrani and then on the 18th moved forward again to Fort Maddalena (LG122) and I located my wing headquarters close to them. In the days before the start of the operation we tried to achieve a measure of air superiority by conducting fighter sweeps often of wing strength. As Bobby Gibbes of 3 RAAF Squadron wrote in his diary on 16th November:

Did a patrol this morning with 112 Squadron and 8 Squadrons. [Actually 3 RAAF.] Went in north of Bardia and came out at Madelina [sic]. Passed two Hurry squadrons patrolling over our forward troops. A dashed nice sight to see so many of our machines on the job.

We also escorted bombers and tactical reconnaissance ‘Tac-R’ aircraft with the aim of impeding the enemy build-up of supplies and of establishing enemy armour locations which we then strafed. In the event, we proved remarkably successful in preventing the Axis air forces from observing the movement and concentration of our ground forces immediately prior to Crusader.

The aim of Operation Crusader, which began on 18th November, was to push back the Axis forces and lift the siege of Tobruk. It began with XIII Corps, which included most of the armour, moving boldly round the enemy’s open flank, aiming for Tobruk. The operation got off to a good start and for the first few days there was a complete absence of enemy aircraft as their airfields at Gambut and Gazala were waterlogged by the rains that had hit the coastal strip. However, this soon changed as the ground dried and Me 109s began to operate from the airfields west of Tobruk. The enemy fighters sometimes surprised us by putting in an attack on our fighters and then using their superior performance to climb away before we could reply. There was a radar listening post in Tobruk which should have been passing us news about the approach of enemy aircraft from the west but in practice we got very little information of use from them.

Accordingly, on Saturday 22nd November, I decided to fly to the besieged fortress of Tobruk to organise the airfield facilities for fighter operations and to find out why the post there was failing to give us early warning of the approach of aircraft from the west.

That afternoon, with an escort of two Tomahawk squadrons, 112 (Shark) Squadron and 3 Squadron of the Royal Australian Air Force, I set off in my Hurricane II for Tobruk. We were well on the way when at 4.15 p.m., south-east of El Adem, we were intercepted by a group of perhaps twenty Me 109s. Bobby Gibbes again wrote in his diary that day: ‘They straight away climbed up into the sun and came down onto us and started to dogfight. Soon got sick of that and formed a big circle about 2,000 feet above us and came down in twos and threes from all directions. The wingco, Pete Jeffries came back, "Rosier and 112 bloke are safe".’

After about twenty minutes, on breaking away, I saw a Tomahawk of 112 Squadron diving down streaming white smoke. I followed it down. He lowered his undercarriage and forced-landed, only a few miles away from an enemy column which I had noticed. In order to prevent the pilot falling into the ‘bag’ I decided to try and rescue him. I landed my Hurricane alongside the Tomahawk and the pilot, Sergeant Burney, an Australian, ran across to me. I jumped out, discarded my parachute and he climbed into my cockpit: I sat on top of him, opened the throttle and started to take off. Then disaster struck. Just as I started my take-off run my right tyre burst. I accelerated but the wheel dug into the sand and we ground to a halt. There was nothing to do but abandon the plane.

At that time it was nearly dusk and, as there was an Italian armoured column about two miles away, we ran to the shelter of a nearby wadi. After some time as there was no sign of the enemy, we returned to the aircraft and I quickly removed all my possessions from the Hurricane, including my wife’s photograph and the silver tankard I had been given by Pete Wykeham, and hid them under some nearby brushwood. Taking some food and water we returned to our hiding place where we planned to spend the night. A little later, trucks arrived and Italian soldiers began to search for us. They found all my possessions but although they came within yards of where we were hiding behind some rocks, they did not see us.

The next morning, anxious to get as far away as possible from the scene of our landings, we set off in an easterly direction to walk the thirty miles or so back to our lines. That night, using the Pole star to navigate, we found ourselves in the middle of some German tanks and lorries. We started crawling on our hands and knees and I thought the game was up when lights came on and we were twice challenged by sentries. Eventually, when all became quiet we continued walking. As dawn was breaking we found ourselves still close to the enemy force who were searching for us on motor cycles. We therefore made for the shelter of some brushwood surrounding a dry well which was the only bit of cover for miles around.

At about 8.00 a.m. that morning (24th November) we found ourselves in the middle of an artillery battle with shells falling on and around the enemy force close to us, which immediately began to disperse and withdraw. We then heard unmistakable orders being barked out in English. I decided that the best thing to do was to make a dash for it, so we ran until we eventually reached the artillery unit. We were at first greeted with suspicion but were soon given some tea and food and sent on to an armoured brigade headquarters not far away.

They welcomed us and provided us with a truck and driver to take us to Fort Maddalena. En-route, as we approached a South African armoured car unit, shells started falling around us and a number of enemy tanks appeared about two miles away coming straight towards us. The enemy force which we had encountered had broken through and was heading east towards the Egyptian frontier. The South African major’s last words to us were, "I think we are the last line of defence before the ‘wire’". So we turned round headed east and went like the wind. Later on we were strafed by 110s but our fighters appeared and shot down four or five of them. Again we passed a most uncomfortable night not knowing the position of the Hun tanks but got back to Maddalena the next morning – the 25 th.

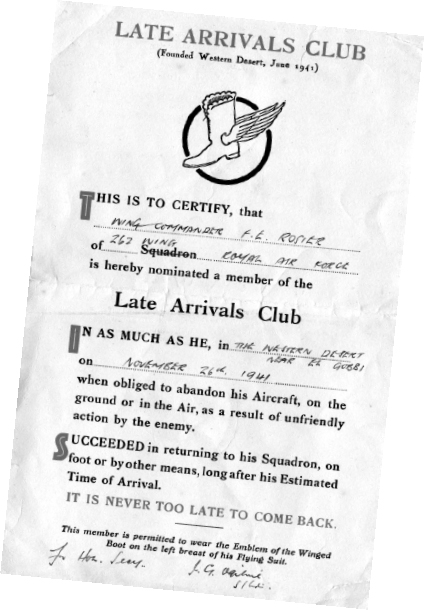

When we reached Maddalena we were given a heart-warming welcome by Bing and others. The last thing they had heard about my whereabouts was from one of the Tomahawk pilots who had seen ‘the wing commander going well on the tail of a 109’. I had been reported ‘missing’ and Wing Commander H.A. ‘Jimmy’ Fenton had taken over the wing in my absence. On my return Jimmy left to return to Sidi Haneish where he was in charge of our reserves. As a result of this escapade I became a member of the Late Arrivals Club.

In retrospect, I doubt whether I could have coped for nearly three days in the desert on my own. It was Sergeant Burney who gave me the will to continue for I felt responsible for him and I could not possibly have let him think that my confidence showed signs of wavering. Burney was a brave, resourceful and determined chap who never lagged behind or complained, in spite of his raw feet caused by ill-fitting flying boots. I was wearing my suede desert boots. He was an ideal companion, a typical down-to-earth Australian. Unfortunately, soon after being commissioned, on 30th May l942, less than six months later, he was shot down and killed.

It was not until thirty years later that I learned it was the Guards Armoured Brigade that had befriended us. Colonel John West, from my personal staff at AFCENT, remembered their astonishment at seeing two bedraggled men walking into their camp from the wrong direction. As a twenty-year-old lieutenant in the Royal Corps of Signals, John West had been attached to the recently formed Guards Armoured Brigade. Poor old John, I saddled him with the responsibility for what I deemed were the deficiencies of army communications at that time. However, I had the grace to tell him that I still remembered the marvellous reception we were given and thanked him for the army’s first class help and hospitality.

Back in harness there was no respite as, after some initial successes the 8th Army suffered heavy tank losses as the counter-attacking German armour penetrated our scattered defences. Our LGs at Maddalena were threatened and we had to take immediate action to safeguard our fighters from the approaching German armoured column by sending most of them back to the rear bases at Sidi Haneish. My wing HQ also ‘retired as a precautionary measure’. Most fortunately for us, the German tank force turned north when ten miles away from our airfields.

On 28th November I wrote: ‘Our air force is doing magnificently and we have at the moment unquestioned air superiority.’

The next day I flew to Tobruk. This time the trip was uneventful. On 1st December I wrote: ‘Had my first party last night. One of the squadrons here was celebrating its 100th victory and the award of the DSO to their CO.’ That day I again flew to Tobruk returning two days later.

3rd December

I got back this morning from the stronghold and thoroughly enjoyed myself there, other than for the discomforts caused by spasmodic shelling. The accommodation there was extremely good, everything below earth. The dugout I slept in had an Italian wardrobe and dressing table and even had a tiled floor.

I hope quite optimistically that we shall clear up the Huns during the next few days and then we shall have a clear run through to Tripoli.

It’s 8.45 in the evening and I’m comfortably sitting down in my office tender, with the wireless giving out sweet music, and my nightly glass of whisky and water in front of me. The only thing I am annoyed about is the absence of your photograph in front of me. How I hate the thought that a blasted Italian has probably put it in his bag as a keepsake.

We have moved about 150 miles west since mid-October when we were known as the Matruh Wing. The climate here is quite different – quite warm during the day but intensely cold at night.

In the confusion of battle it became clear that our army commanders and their staff were uncertain or probably entirely ignorant of the position of some of their units. Afraid that our air forces would be unable to differentiate friend from foe, the army established bomb lines far in advance of the calculated position of their troops. This greatly limited the assistance we could give them. Other than in special cases we were not allowed to attack any units within this bomb line. This often seemed ridiculous to us for more often than not we knew far more than the 8th Army about the position of their own units and of the enemy. What is more, we had passed this information on to them in the first place.

In early December, after a week of heavy fighting, the tide turned and by 7th December Rommel’s forces began to withdraw and Tobruk was relieved. In this, the second conquest of Cyrenaica the RAF was well to the fore. The positive effect of air action cannot be over-estimated. Offensive fighter action had limited enemy air attacks on our army. Attacks against enemy airfields at Gambut and El Adem and on supply columns and dumps had inflicted much damage and our light bombers had been most effective. In addition, from our armed reconnaissance sorties we were finding and attacking many more targets than we received from army calls for support.

On 8th December Bing Cross was injured when his Hurricane crashed on landing following a sweep with 274 Squadron over the Gambut airfields. While he recovered in hospital he was replaced by Jimmy Fenton and I became the senior wing commander or as I wrote to Het, ‘Since then I have been running the whole shooting match’.

11th December

The war here is going well and within two hours I hope to have my HQ functioning where the majority of the German air force functioned a fortnight, or even a week ago [Gambut]. Today is in point of fact most difficult. If you can visualise a bus owner at Newcastle trying to control a fleet of buses operating between London and Brighton, attempting to prevent them being shot at or bombed every hour and also trying to take a personal interest in all of them, then you have the position in which I am working today.

During our advance across Cyrenaica that December, in order to speed up communications, rather than encrypted signals the AOC often used voice radio to speak to me, using language that we were confident would not be understood by the enemy.

After Gambut, east of Tobruk, our next move on 15th December was to Mechili and it was whilst there that we had a visit from a female reporter from the American magazine Time & Life. We threw a party, which was also attended by Buck Buchanan, the CO of 14 Squadron, a Blenheim squadron. He was a fair-headed, good-looking chap who was exceptionally brave. A few weeks later I landed at Buck’s airfield very early one morning. On enquiring about his whereabouts I was told that he would be along shortly but, as time went on, I began to lose patience. At last he arrived, with apologies. I heard later that the reporter, Morley Lister, had been staying with him in his tent for the last day or two and that she had accompanied him on the odd operational flight.

It is hard to believe it but his squadron thought so much of him and were so loyal that they kept it all quiet. However, it was not long before Mary Coningham got to hear of it. Buck was promptly removed from his squadron and posted to a ground job in the Delta. Buck’s next posting was to Malta to command a Beaufighter squadron. One day he was shot down over the Mediterranean but he and his crew, who were uninjured, got safely into their dinghy. Eventually rescue came but by that time Buck seemed to have lost the will to live and had died. This seemed unbelievable in such a dynamic character. He was a great loss.

15th December

We are now based fairly deep in Hun territory, the battle not far away from us. Our fighters are still doing extraordinarily well – score day before yesterday was fifteen-three.

I’ve just been outside to see the gallant 229 pass over on their return from patrol, Johnny Loudon is the wing leader of that and one other squadron. I saw the 229 chaps yesterday. Up to date their losses have been few and they are in fine form. An Me 109 was shot down here the day before yesterday and I interrogated the pilot – he was twenty-seven years of age. I was not impressed and was thankful that I was British.

On 22nd December I moved the wing HQ and fighter squadrons to Msus about sixty miles south-east of Benghazi. During December continuous daily operations supporting the advancing army took its toll on the squadrons and many were temporarily withdrawn to regain their strength. Bing Cross returned to duty on the 29th and a few days after his return he and I took the opportunity to visit Benghazi where, at the invitation of the Middle East RAF Press Unit, we sat down to an excellent lunch with plenty of good Chianti and cigars. It was a welcome change from our normal fare.

We stayed there for about ten days before moving again in early January to Antelat, near Agedabia, about forty miles south west of Msus. Here three landing strips had been constructed and XIII Corps had established its headquarters. During these moves I, together with those of my wing HQ who had not been sent to Benghazi to control the fighters, joined Bing Cross’s 258 Wing. Operating from Antelat allowed our fighter force to range over the enemy’s troops south of Agedabia, where Rommel had decided to halt his retreat, and to strafe El Agheila airfield further west.

6th January 1942

I am sorry that this is the first letter I have written for three weeks, an awful long time I know but conditions have been such that letter writing has been impossible. I’ve had about ten weeks in the desert now without a break and I feel that I deserve forty-eight hours leave, so I shall fly the odd 600 miles to Alex. Then I shall return for the advance to Tripoli.

Little did I know!

The fighter sweeps from Antelat provoked little opposition from the Luftwaffe but the flak from the enemy ground troops was always heavy. Having returned from forty-eight hours leave in Cairo, other than it being very cold, I remember that on 17th January we had a visit from both Air Marshal Tedder and Air Vice-Marshal Coningham who spoke to our squadron commanders.

Bing and I were at Antelat when, on 20th January, it started to rain heavily. Our landing strips rapidly turned to mud and became unfit for taking-off and landing. The situation was serious in the extreme, for it meant that our fighter force of over 100 aircraft would certainly be destroyed on the ground by the Luftwaffe fighters if they became aware of our predicament. Our only defence was a Bofors gun unit. That afternoon Bing and I, having discussed the problem with the squadron COs, decided that every effort must be made to make at least one of the strips serviceable.

That night it rained again and although it had stopped by the morning, we began our attempt to get the aircraft away. At a meeting with the squadron COs, one said his strip, though pretty bad, was better than the others because it had been built on a slight ridge. After examining it, we decided to try to make it usable by filling the holes with stones and scrub bushes. Soon, 2,000 officers and men of the two wings were working on the strip and by early afternoon, when it seemed marginally satisfactory, we decided to try it out.

A Hurricane was manhandled through the mud and, much to our relief, took off safely. By nightfall three squadrons had got away, flying east to Msus. The remaining three followed the morning of the 22nd.

That morning Bing went to XIII Corps HQ where he was told that Rommel’s forces had advanced towards Agedabia during the night ‘but it was probably just a reconnaissance force and wouldn’t get far’. After briefing me on the situation, Bing instructed me to remain at Antelat with a skeleton wing HQ, to keep in touch with XIII Corps HQ and to do what I could to assist our fighters by giving them the latest information by R/T on the enemy movements. He then left for Msus.

Later that day I heard that Rommel’s forces had actually broken through our defences. It was the start of an advance that took him back to the Gazala line of defence and seven months later to El Alamein; so much for a ‘reconnaissance’ force.

For me and my wing HQ, it was only a matter of hours until it was too dangerous to stay at Antelat. So, along with XIII Corps HQ on the night of 22nd January we moved back to Msus, some forty miles away. On arrival we found that 258 Wing HQ, together with the fighter force, had that morning moved back to Mechili, a further eighty miles east.

I decided to stay at Msus whilst I could continue to act as a forward information post for our fighters, having done so previously in Antelat. But a few days later I was told by XIII Corps HQ that they were moving back due to the proximity of the enemy and that I was to do the same. I ignored this and stayed on, I think, for another couple of days. I felt safe because at first and last light I was informed by our reconnaissance aircraft of the forward position of the enemy troops who had not advanced from Antelat. Consequently I was able to assess the risk of staying. When I did move again on 26th January I joined up with Bing’s wing HQ at Mechili. As a result of the German counter-attack and our hasty withdrawal, I was unable to write to Het until this date:

26th January

It seems an eternity since I last wrote to you and the news I have accumulated during that time is tremendous, but most of it concerns movements which are secret. Anyway everything is most depressing at the present time. I myself do not like progressing with my back to the enemy.

The army seem to have excelled themselves in this theatre of operations by displaying bone-like ignorance at all times. I have a shave every morning which comforts me into thinking that we are carrying out an organised withdrawal rather than a disorderly retreat. But still our air force, working sometimes like today for example under almost impossible conditions, is roaming round the sky maintaining air superiority and destroying enemy troops and transportation on the ground.

I think that after the war, unless I have lost interest, I shall go into politics and press for an air force army and air force navy.

I spent forty-eight hours in Cairo a few weeks ago (12th/13th January) – a glorious time of complete abandon and bad headaches which has done me the world of good. On my way I landed near Alex and telephoned for transport. Wing Commander Grant-Ferries MP picked me up and took me to the home of a wealthy cotton grower where I arrived, unshaved and in my desert suiting, at a cocktail party. After summoning up my courage (after three drinks), I craved a bath and strangely enough they said yes to my odd request.

27th January

Two o’clock in the afternoon amidst a raging sandstorm feeling still depressed because we, under these weather conditions, are so utterly useless. Actually nine enemy fighters have just passed close to us but obviously failed to sight this place.

28th January

Had no further opportunity of writing yesterday as a general flap developed and I was up most of the night making decisions about movements. I expect we shall move from here during the course of the day.

Rommel, having caught the British XIII Corps off balance, now made a sudden turn northwards and on 28th January Benghazi fell.

Having six squadrons on one airfield at Mechili was too much of a risk so 258 Wing HQ and the fighter squadrons withdrew a further sixty miles east to Gazala where three landing grounds had been prepared next to the coast road. Since 2nd January we had moved our fighter force of over 100 aircraft four times, one move forward and three back. Apart from the six unrepairable fighters we had left at Antelat, we had lost nothing – not even a vehicle.

We were on the move for the following three days. On 1st February, because the enemy’s advance made our airstrips too far forward for safety, we moved back from Gazala and I set up my wing HQ at El Adem, fifteen miles south of Tobruk. Bing’s wing and nearly all the fighters then moved to the Gambut group of landing grounds further east.

1st February

And now darling I think you must have some idea of what our life consists of. We arrived at this place yesterday and we are operating today. Quite a number of my chaps including the adjutant have not yet turned up so I presume that they have been cut off and captured on the way from Benghazi. This is a major blow as he was a very good adjutant.

Luncheon interval – there are talks of an impending move.

1.30 p.m.Yes we have to move because of the presence of the enemy. It will mean another night move, blast it.

10.30 p.m. We have done the journey better than I anticipated darling and the chaps have already dug themselves in here and we start operating at dawn tomorrow.

We had to move again last night and we are now settled at an aerodrome we were at two months ago. [El Adem]

Once settled at El Adem and Gambut the primary task of our fighter force then became the air defence of Tobruk, our main supply port.

The enemy air force was constantly active during this time, carrying out frequent bombing raids against Tobruk and strafing attacks by fighters, which now included the superior Bf 109F. With good tactical information from the Y Service and a radar unit at Gazala we were able to intercept many raids but the strafing attacks were difficult to counter and they destroyed many of our fighters on the ground.

One day, much to my delight, part of a detachment I had sent to Benghazi for fighter control duties many weeks before and who I thought had been captured turned up. With the exception of a very brave RAF chaplain, who was wounded and captured, they had managed to evade the enemy patrols and under the most stressful conditions had walked over 200 miles from Benghazi to Gazala. It was a tremendous feat.

7th February

Since I last wrote we have had a particularly active time. Our ground strafing has been so very successful that the Huns have been trying to fix our fighter force by bombing and ground strafing our airfields by day and night.

8th February

Having a most exciting day darling. The 109s have reappeared and dog fighting seems to be the order of the day. We put on a big show today and the chaps are just arriving back in dribs and drabs which means they have had a fight.

We have not had a very good day unfortunately. Valour does not always make up for inferior equipment.

I’ve invited some Hussars over for dinner tonight. We can give them some gin but that’s about all.

9th February

At 5.00 a.m. a stick of bombs fell right through our mp and rather disturbed the peace of mind of 262 Wing. Still, we had a good dividend with the CO of the joint squadron I had last July shooting down an He 111. Then to cap everything we shot down a Ju 88 inflames – breakfast was a cheery meal. It is now midday and half an hour ago we shot down a 109 close to the aerodrome.

10th February

I am sending a truck all the way back to the Delta tomorrow, darling, so I shall send all these letters with it. (26th January to 10th February).

I have a new adjutant arriving today thank goodness. My camp commandant has absolutely no idea and as I have been so busy with operations I’ve had no time for administration.

By mid-February the front line had stabilised between Gazala and Bir Hacheim and it was at this time that Bing and I received a signal informing us that we had both been awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO). I remarked that had we been advancing rather than retreating we might well have got VCs.

The citation in the London Gazette on 13th February 1942 read:

‘The King has been graciously pleased to approve the following award in recognition of gallantry displayed in flying operations against the enemy:

Distinguished Service Order

Flight Lieutenant (Acting Wing Commander)

Frederick Ernest Rosier (37425)

This officer has commanded a fighter wing since the commencement of operations in Libya both in the air and on the ground. His courage and efficiency have been inspiring throughout. On one occasion, when one of our fighter wings was being attacked by a large number of aircraft, Wing Commander Rosier joined in the engagement. When breaking clear he observed one of our pilots who had been forced to land in enemy territory and, in an attempt to rescue him, Wing Commander Rosier landed his aircraft. He was unable to take off again owing to the close proximity of enemy forces. Nevertheless, both pilots eventually got away, and, after many narrow escapes, succeeding in regaining base after a period of three days. Wing Commander Rosier is an outstanding fighter pilot and leader.’

13th February

I met some old friends of mine last night at Tobruk and Freddie, having just been awarded the DSO, got horribly tight. I am amazed darling and so proud. The AOC had a telephone message from Middle East HQ yesterday morning saying that both Bing Cross and myself had got DSOs. I didn’t think so before but now I know that it means a hell of a lot to wear that little bit of ribbon.

Later that month Air Commodore Thomas Elmhirst arrived at Air HQ to take charge of administration. One of his first tasks, with the help of Bing and me, was to plan the reorganisation of our two fighter wings.

4th March

From now on darling address letters to 262 Wing or 239 (Offensive) Wing. I don’t know why they’ve changed our numbers unless it’s an attempt to fox the enemy.

Had lunch with the AOC two days ago. There was a real, live woman there. I was so shy that after one beer I told the story of the elephant and the mouse because she told a foolish (funny) American story. I believe she was the journalist wife of a well known US politician.

19th March

I’ll soon have a new job my dear, and will probably become a deputy group commander. I’ve heard rumours for some time that I might get further promotion but I stayed with the AOC last night and he mentioned nothing about it.

23rd-24th March

After the party I finished up by playing the violin for a couple of hours.I managed to get the violin from Benghazi. It’s quite good and belonged to an Italian officer...I’ve built a magnificent ops room here, along the lines of those at home. It’s all below ground.

What an awful day. The worst we’ve had since the terrific rains. We had a gale ‘kamseen’ all night and now it is blowing the most awful sandstorm and it is also bitterly cold.

26th-27th March

A Hurricane has just crashed on the aerodrome. Pilot is OK but he’s a fool. Of course I told him so.

I’m going to tell all my officers today about the future of the wing. I’m rather depressed about it...

Had the most awful party last night. It was a farewell party. I made a speech – a magnificent drunken speech.You see darling, the wing was my baby. I created it, I trained it and I hate to leave it. I’m told that we were all trying to stand on our heads at 2.00 a.m. What a fine relaxation!

31st March

Well darling mine the fighting 239 has gone, and I am left. No longer do you address your letters to 239 Wing but to 211 Group.

Since last November we have only lost three bombers from enemy fighter action, when we have provided fighter escort. It’s very, very pleasing.

My tent is still surrounded by a carpet of flowers. They smell beautifully in the evenings.