EL ALAMEIN AND WESTWARDS

211 GROUP AND THE WITHDRAWAL TO EGYPT – 1942

On 2nd April 211 Group was formed with three new mobile fighter wings. They each controlled three or four fighter squadrons equipped with the same type of aircraft, Kittyhawks and Hurricanes; all based where possible, on the same airfield. I became second in command of the group with Group Captain Guy Carter taking over as OC from Bing Cross, who was posted back to Egypt. Guy had fought in the First World War but had no operational flying experience in the Second. He was a delightful man and a great character, and left me with my team of wing commander controllers to cover the detailed planning and execution of operations. He then devoted most of his time to maintaining close contact with the wings and squadrons. I shared his caravan and sometimes during ‘quiet’ evenings we had a glass of Zibib together. We became firm friends. In an article of 17th February 1943 headed’ Salute to the Tacticians of the Desert Air Force’, Richard Capell, special correspondent of the Daily Telegraph, wrote of Guy: ‘His command was then that of the principal fighter group (No.211) with Wing Commander Rosier as his second in command. It was an admirable combination...’

The next few months were difficult as we tried to maintain air superiority by offensive action while defending our LGs at Gambut and Tobruk with a depleted force, as many of the squadrons had been withdrawn for rest and re-equipment and some had been posted to the Far East. The remaining squadrons fought with great courage but the Hurricanes were no match for the 109s. We needed better, and more fighters – Spitfires and Kittyhawks.

The HQ of Group 211 was situated with the fighter wings at Gambut while I and a team of controllers and operations personnel stayed on at El Adem.

2nd April

It poured with rain yesterday afternoon giving fresh life to the carpet of flowers round my tent. I’m told it is the last drop of rain we shall see for about nine months. Libya – Oh my Libya!

From my operations room at El Adem I had direct communication with a radar unit at Gazala which had been withdrawn from Benghazi just before Rommel’s attack on the port. This radar proved to be most useful as it could detect and track aircraft which had taken off from an important German air base at Martuba. For example, using this information we were able to intercept some of the Luftwaffe raids on their way to Bir Hacheim where Free French troops were based. We were also able to see the build up of Stukas and escorting fighters setting off for attacks against Tobruk. This allowed us enough time to try to intercept them en-route.

Another valuable source of information was a tactical intercept Y Service unit, situated close to my HQ. It had German and Italian speakers who listened in to enemy transmissions, ground-to-air and vice versa, and informed us of what the enemy air forces were up to. They became so expert that they were able to recognise the identities of some of the enemy formation leaders.

On one particular day, when rain had made the Gambut landing grounds unusable and our aircraft were grounded, the Y Service informed me that there was a build up of enemy fighters and Stukas from Martuba and that there was a strong possibility of a raid on Tobruk. Knowing that the Germans also had their equivalent which monitored our transmissions, I decided on the spur of the moment to try to hoodwink them and to see what happened.

As the Italian Stukas, escorted by German 109s, set off to attack Tobruk and were tracked by our radar at Gazala, I scrambled two squadrons of imaginary fighters telling them by radio to keep low so that they would not be seen by the enemy radar. I then heard from our Y Service that the enemy had picked up my transmission and was relaying it to the force, telling them that they could expect to be intercepted by British fighters. My next order to the ‘fighters’ was to maintain radio silence, to climb to a certain height and to fly on fixed compass headings, continually updated by me, which should lead to an interception. My last transmission was to inform our mythical fighters that they should soon see the enemy raid approaching from a certain direction. As the incoming raid got closer I thought that my ruse had been unsuccessful, and then the telephone rang. It was our Y Service with the news that on receipt of my last transmission, the Stukas had jettisoned their bombs south of Tobruk and were heading for home. I was told by the Y Service that the German leader of the fighter escort had told the Italian bomber leader in no uncertain terms what he thought of him! The ruse had worked; the enemy had been completely hoodwinked and there was much joy in our camp.

Unfortunately as the enemy reached and then broke through the Gazala defences west of Tobruk in late May, the radar had to be withdrawn and we could no longer track enemy raids and therefore our ability to make planned interceptions came to an end. Fortunately the Y Service continued to tell me when enemy raids were building up over Martuba, the size of these raids and their composition; e.g. Stukas and the 109s. This enabled me to position our fighters where they had a reasonable chance of engaging the enemy on their way to Tobruk.

16th April

Things are very static out here at the moment, but it won’t be long before one side or the other takes the offensive.

3rd-5th May

Dearest, my promised leave was only forty-eight hours. I went to Cairo first which was awful, to see about pay, and spent the rest in Alex, which I thoroughly enjoyed. I even played a game of squash. I went to a cocktail party and had three or four baths a day and was made much of by ‘Alex’ society.

Did I ever tell you darling that I am second in command of the group. I have the three wing commander controllers, all of them proper whereas I am only acting. Normally I don’t do any controlling but if a large enemy force is about either the group captain or myself is brought in.

I had a case the other day where there was a formation of over thirty Huns going down to attack one of our army positions. At that time we had seven fighters in the air and there was no time for our striking force at readiness on the ground to intercept them. I had to decide whether to leave the Huns alone or attack them with the aircraft available. It was a dreadful decision to make. I decided to attack. The initial result seemed awful and caused some remorse – only two of our seven came back, but it got better. Our casualties eventually were one killed, one missing, two wounded and the enemy had four shot down and some damaged. I think it was worth it.

Just had lunch darling with the GOC in C, AOC and our guest was the King of Greece.

7th May

Last night I went along with the group captain to 73. We drank rather a lot of beer but I went on duty at about midnight. I feel fine this morning however.

8th May

I forgot to tell you in my previous letter that I met Dickie Bain [the CO of 43 Squadron when the author was at Tangmere] in Alex. I had two or three drinks with him for old times sake. He had been burnt in very nearly the same places as I have. An aircraft crashed on the same ship that got me away from England and set fire to some others. Quite a number of people were killed so Dickie was probably very lucky. I think my short leave in Alex did me the world of good darling. Although I had very little leisure time, being too occupied playing squash, going to cocktail parties, speaking French and even playing three games of billiards, and feeling awfully tired it was a terrific change.

11th May

The Hun has been fairly quiet all day but he might come over with his Stukas later as there is shipping in Tobruk. At least I anticipate an attack.

We had an extremely good result two days ago when one of our squadrons knocked down two 110s and thirteen Ju 52s. The Ju 52s were full of troops and they were shot down about forty miles out to sea.

The good weather hasn’t lasted. I never want to see sand again. There is enough of it in my hair even now to provide amusement for a child making sandcastles.

The offensive will soon start again darling. It will be so much better than this static warfare. Whether the Huns will start it however is in the lap of the gods.

17th May

Billy Drake (do you remember him at Tangmere?) has just arrived up here as a supernumerary squadron leader. Met him at a conference we had this morning. He still looks as young as ever.

We’re being fairly active this morning bombing the Hun with our fighter bombers. We get up too early for them.

Rommel’s next offensive started at Gazala on 26th May. The battle started well for the allied troops but, after nearly four weeks of fighting, the Axis forces broke through and Tobruk fell. With the 8th Army by then under General Auchinleck’s leadership, defeated and virtually out of tanks, we withdrew over 300 miles in an orderly manner to behind the El Alamein line where we held firm, reaching there in early July.

30th May

The battle has started again and I am no longer bored with the state of static allied troops warfare. I think we are doing well. For the first time since 1939 the army seems to have come into its own. The other day I went to Alex for a conference with the navy. I stayed down there for a day and brought back with me 200 eggs, five crates of beer, some gin and enough dinner – Coq au Vin – for four which, in its earthenware dish, was still warm when I arrived up in the desert the same evening.

2nd June

The battle has started again and we have won the first round.

As far as the air force is concerned the squadrons have been hard at it, strafing and bombing enemy transport. Our losses have been fairly high, quite naturally. I should have liked to have seen our force used differently. First of all I should have gained local air superiority by using our air force for its own purpose and not as army coop squadrons. When this had been achieved, then we could have switched over to ground strafing and bombing with much fewer losses. Still – can’t be helped. The desert is not what it was.

Had the worst storm I have ever known this evening darling. The wind came up to 70-80 mph, an awfully hot wind, 120° from the south. Visibility was without exaggeration about a yard. It then started to rain and the mud came down.

4th June

The battle is still on. The Huns lost the first round, but they are coming back for more. It is so important that we win this battle, much more important than is generally realised.

It’s about 11.00 p.m. and I’m sitting in the ops room waiting for the Huns to come over. I did some night-flying two nights ago by the way.

On 17th June operations reached a crescendo as, following the fall of Bir Hacheim on the 11th, the Gazala position had become exposed, resulting in the withdrawal of the 8th Army. By 14th June the retreat was in full swing and two days later I was forced to move back from Gambut, first to Sidi Azeiz and then on the 18th to Sidi Barrani.

A few days before Tobruk fell on 22nd June I had sent a small team including a controller, Squadron Leader Young, there. The job of this outpost codenamed ‘Blackbird’ was to provide forward control of fighters, and I anticipated that they would return if or when Tobruk was evacuated. It was not to be, for one afternoon I had a call from the controller saying that German troops were approaching him and his team. He just had time to say goodbye before the line went dead. The thought that I had sent them there only to become prisoners of war was disturbing, but there was no time to dwell on this because an approaching enemy column was not far away and I had to organise a hurried withdrawal from El Adem to the main HQ of the group.

During Rommel’s advance his columns came under frequent air attack, whilst our withdrawing army units, often moving bumper to bumper along the coastal road, saw little of the enemy air force. There is no doubt that action by the fighter-bombers of the Desert Air Force, the light bombers, the Malta-based squadrons and the Royal Navy had weakened Rommel’s forces to such an extent that he was unable to penetrate the Alamein defences and advance further.

During the retreat, which lasted for seventeen days, I was kept busy all day and most of the night planning the next day’s operations and keeping a close watch on the number of our casualties, on the numbers of reinforcements we were getting and on the availability of aircraft and pilots.

It was exhausting moving backwards. The wings and squadrons were moving by night and attacking Rommel’s forces by day. Every time a squadron pulled back to a new LG the fuel bowsers and ammunition lorries were waiting. There was no panic. Unserviceable aircraft which could be moved were towed behind three-ton trucks: the ground crews kept up an amazing serviceability rate of eighty per cent most days. The ground and aircrews deserved the highest praise.

During the withdrawal we were operating at extreme range, which meant that we were unable to escort the light bombers. The army were fixing bomb lines too far ahead of our army formations, and this severely limited close support; and the problems of getting fuel up to the forward airfields were immense. In addition, the prolonged and intensive operations had so weakened our fighter force that the twelve remaining squadrons could barely muster 100 aircraft. Despite this, we had overrun the enemy air force – no mean feat.

The withdrawal ended in early July with the 8th Army in a defensive position of strength between the Mediterranean and the Qattara depression, 211 Group continued to operate in support of the army until we reached a clutch of landing grounds at Amariya, twenty miles or so from Alexandria.

8th July

Sweetheart darling mine. How you must have worried about this campaign. I hate this retreating. After the first week I could visualise what was going to happen. Our retreat has been terrific and we have left our bases on occasions when Hun tanks have been within fifteen miles of us (and nothing to protect us). Darling mine things have been so disrupted and we have all been so tired that letter writing has been out of the question.

We are not so very far away from Alex, and I’m going in tomorrow. But of the future – we either defeat him and go forward, stay as we are now, or withdraw into Egypt.

I don’t think that there is any doubt that the RAF has saved the day. The chaps have worked harder than in the Battle of Britain under conditions ten times as bad. Eleven different sets of landing grounds in seventeen days, darling, and we operated continuously.

On one occasion during the withdrawal AOC Coningham accused me and Guy Carter of lying about not having received his orders to intercept a raid with Kittyhawks rather than Spitfires. He was livid and so were we. He refused to see me. Some two years later in May 1944 when he had become C-in-C of the Second Tactical Air Force he invited me to lunch at his farmhouse near Uxbridge. During lunch he apologised. It transpired that many months after the incident he had found that his wing commander ops, concerned about security, had not passed on his orders in full deciding that it would be more appropriate for 211 Group to decide for itself which particular aircraft to use. I thought at the time that it was a great pity that Guy was not around to receive this apology: he had been killed in Italy when he was hit on the head by an axe which had been dislodged during a bumpy landing.

By the time we arrived at Amariya in early July I was dog-tired for I had been on the go, with no more than four hours rest a night, for over six weeks. Now was the time for relaxation. Our fighter squadrons were able to concentrate on training for there was little requirement for active operations, and their personnel as well as ours in the group HQ were able to take some leave. Other than the odd weekend in Alexandria and Cairo, I had taken none since leaving the UK more than a year previously. There I enjoyed the pleasures of the fleshpots but always the first priority was a haircut, shampoo and bath at the Cecil Hotel in Alexandria or the Continental in Cairo. On my return to the desert from these weekend breaks my overloaded Hurricane was filled with fresh fruit, canned beer and large dishes of Coq au Vin and the like supplied by the best restaurants in those cities.

20th July

I went down to Cairo last Friday afternoon, to have a medical board on the Saturday morning. Do you know darling the board was for a permanent commission. [Technically I still had a short service commission as I had not completed the engineering course at Henlow in 1939.] I was rather angry about it as I have already done two for the same thing. However, I was AB which pleased me.

The group captain has been rather ill for the past fortnight with sandfly fever and consequently I have been extremely busy.

On 31st July, somewhat reluctantly, knowing I would miss Winston Churchill’s morale-raising visit to North Africa, I set off for Palestine on my long leave in a halftrack, with a V-eight engine, which had been given to me by grateful sappers in Tobruk.

10th August

I’ve just arrived back from ten days leave and I’m feeling as fit as a fiddle. I set off from here on the 31st at dawn and drove down to Cairo where I had breakfast and a shampoo in the Mena House Hotel near the pyramids. I had lunch at the French Club at Ismailia and then started an awful drive over the Sinai desert to Beersheba, then on to Gaza, arriving at Tel Aviv about 8.30 p.m. That same evening I walked into a hotel and ran into MacDougall who was in 43 until 1937. He promptly invited me to stay in his house (he is station commander at Ramleh). I went to Beirut and Jerusalem, played squash every day, drove back and finished the last two days of my leave in Alexandria.

I did the journey in a most wonderful car darling, which was made by engineers in Tobruk. It’s got an open body and a new 30 HP engine, and it does 85 mph.

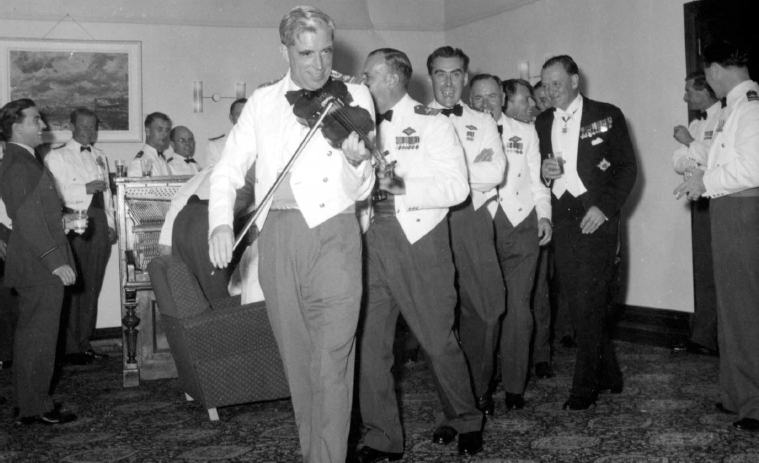

Whilst we were at Amariya I made a few overnight visits to Alexandria, usually starting at the Cecil Hotel, then going to the Union Bar or Pastroudis to eat, before visiting one or more of the night clubs. I remember clearly one of these visits made with a friend of mine, Wing Commander Johnny Loudon. Having removed our badges of rank, I managed to borrow a violin from the band and to the delight, or otherwise, of the guests, I serenaded them whilst my friend followed me around with his hat. I think we handed over the money we collected to the band.

20th August

One of the Spitfire squadrons did well yesterday destroying four 109s and probably getting eight more with no loss to themselves. We will shake the Hun one of these days.

As you may have gathered from the newspapers Winston Churchill had lunch in our mess but unfortunately I was away. I should have liked to have spoken to him. He made a speech, full of confidence.

Things are still very quiet out here sweetheart – the lull before the storm. By the time you receive this I imagine that the issue will have been decided. A quiet air of confidence reigns. If we can defeat his main forces, especially his armoured forces, in this area, then we shall have a clear path to Tripoli. I think I know most of the way blindfolded.

I wonder if you ever gathered my whereabouts during the advance and retreat – Maddalena, El Adem, Gazala, Mechili, Msus, Antelat and then a place just south-east of Agedabia.

During the last part of this advance I pushed Dakin and part of my wing to Benghazi. I spent Christmas Eve at Mechili. On the way back we did the reverse but in addition went to Martuba and Tmimi. You remember I told you about my tent being surrounded by a carpet of flowers. That was at El Adem where we stayed for about three months. Then off to Gambut for a month or so. The sandstorms there were terrible. And then the retreat.

In that late summer of l942 both sides were intent on building up their forces. We began to receive more Kittyhawks to replace the inferior Tomahawks and, thankfully, Spitfires. We were also reinforced by the Kittyhawk-equipped American 57th Pursuit Group. The 8th Army too was strengthened, not least by Lieutenant General Bernard Montgomery who arrived in August to replace General Ritchie following the sacking by Churchill of Claude Auchinleck as C-in-C Middle East. Montgomery’s arrival prompted enormous change in the army. As the new commander ‘Monty’ was able, in a very short time, to instil fresh heart into his men and a confidence which had been lacking.

Montgomery also made it clear that he and the RAF would work closely together. He believed in joint planning of operations. In doing this he was putting into action what had long been advocated by our brilliant AOC, Mary Coningham.

No longer was the ground situation allowed to become so confused that air support was limited. We knew where the enemy were and were able to attack them in relays of light bombers and fighter-bombers. In addition we had been reinforced, so that by the time the El Alamein battle began, the Desert Air Force had some dozen wings containing forty-eight fighter and fighter-bomber squadrons – almost 600 aircraft in all.

Towards the end of August the group was called upon to return to intensive operations, for it was expected that Rommel would soon attempt to break through our defences at Alam Halfa: he tried and was driven back. The battle of Alam Halfa officially lasted from 31st August to 3rd September but our air forces were committed from the 21st August. The victory showed what could be done when land and air forces co-operated closely in the planning and execution of operations – a sensible development which was to be followed in the forthcoming Battle of Alamein and indeed, in the rest of the war. Rommel was defeated and our success marked a turning point not only in the desert war but in the fortunes of the allies.

Alam Halfa was a battle in which our air forces: bombers and fighters, played a major part by taking the offensive. The 8th Army’s role was strictly defensive. During the battle I was again hard at work organising fighter escorts for our bombers, and providing air support for the army (mainly by ground attacks on the enemy forces, and by attacking the enemy air force, both in the air and on their airfields). By day and night the Axis forces attacking the Alam Halfa ridge were bombarded continuously from the air, with our squadrons flying two or three sorties per day against them.

As we were about to start the offensive aimed at, once and for all, driving the Axis forces out of Cyrenaica, I should mention the state of our armed forces compared with those of the Axis. In numbers both our army and RAF had superiority over the enemy, e.g. in tanks and aircraft, but in other respects we were inferior. For example, German leadership (Rommel) was incomparably better than ours; German troops were better led and better trained and the German tanks and their six-pound anti-tank guns were far in advance of ours. If I remember correctly, our anti-tank guns were two-pounders.

As if this was not enough, army communications were poor; orders from the 8th Army headquarters would sometimes be taken merely as subjects for discussion; and some senior commanders in the army still believed that they should have their own RAF squadrons to ‘play with’. This would have been a recipe for disaster.

20th September

I have been quite busy darling. Guy has just got over his monthly attack of sandfly fever, and has gone into Alex to have lunch on the beach. He is going off on sick leave tomorrow for a week.

I went down to Cairo on Wednesday evening to lecture to about 400 army officers. The last battle (Alam Halfa) resulted in quite a victory for us, army and RAF, and the Hun had to withdraw. Funnily enough there was no feeling of blind optimism.

22nd September

On my own again this week. Garvin, the other wing commander, is in hospital with malaria and Guy Carter has gone on leave for seven days. Things are very quiet on the ground and in the air. This will not last very much longer. There will be the most terrific battle. I am always confident.

Then darling, when we defeat him here, the end of the war will be in sight. I am certain of that. Three years is a long time.

I’m going to try to persuade people that for England to launch an offensive on the continent without my knowledge of mobile warfare would be a catastrophe. I want to live with you again.

Received a letter from you yesterday in which you enclosed the small snapshot. It was a wizard photograph of you.

I shall go into Alex fairly soon to do some Christmas shopping. The price of things has gone up considerably since the Americans arrived out here. An American colonel friend of mine gets, with pay and allowances, 900 dollars a month. It seems so foolish that there should be any disparity.

I’ve put all the news in another letter which Paddy Dunn, an old friend of mine, who is wandering around at the moment with Lord Trenchard, will be taking to England. In it I mention how I met Cedric Masterman in Cairo. He has a Beaufighter squadron in Malta and had come over here for a week’s leave. I have also heard that Broady is on his way out here.

Do you remember me telling you that 73 Squadron presented me with a silver tankard. I lost it together with a lot of my kit last November. Three days ago a South African major arrived here with the tankard which he gave to me. He said he had found it in the front of a truck last January when the armoured cars he was commanding shot up an enemy column south of Benghazi. It is now in Cairo being repaired.

This tankard had been given to me by Pete Wykeham in August l941, as related earlier. It had been found with my possessions by the Italians in November and ‘liberated’ from them by the major in January l942.

EL ALAMEIN AND ADVANCE

Following the defeat of the Afrika Korps at Alam Halfa, Montgomery and Tedder began to plan the break out from the El Alamein line. I spent September and October at group HQ planning the air support for the Battle of Alamein which started at 10 p.m. on the night of 23rd October with a thunderous barrage of 456 guns from the British artillery which could be heard back at our base at Amariya. From 19th October our air force had been busy preparing the way. Our bomber force, which had been augmented by ten US Air Force squadrons, attacked the enemy’s landing grounds by night and day, whilst our fighter force, now reinforced by three US Air Force Kittyhawk and three RAF Spitfire squadrons, provided escorts and attacked enemy LGs, lorried infantry and transports. Our main objective had been air superiority and it had been achieved. We had also played havoc with Rommel’s supply lines.

During the battle which lasted until 3rd November when Rommel started his withdrawal, I was on the go most of the time. As the enemy retreated it seemed to me that our advance was much slower than it should have been. For this, we in the RAF, and many others, criticised Montgomery as it appeared to us that he was unwilling to take risks.

31st October

The battle has started. This time we should really clobber the Hun. We have almost complete air mastery and the army have done well so far and I expect our long trek to Tripoli to start fairly soon.

I’m well equipped for the journey. I have a new Hurricane and a magnificent Chevrolet saloon car.

The group captain has promised me that when we get to Tripoli and the campaign is over we shall go back to England together.

From 4th November the withdrawal of the Axis forces began to turn into a headlong retreat, harried all the way by the RAF. The tempo of our fighter operations depended on the supply of fuel and on the range to the enemy airfields. When it was quiet I used to take the opportunity of spending more time with the wings and squadrons, sometimes attending their parties and flying back to my ‘home’ in the dark. At one such party at Martuba I am told I gave a ‘spirited rendering’ of Do You Know the Muffin Man on my violin.

Tobruk was taken on 12th November and by this time the RAF had complete air superiority, making the Axis convoys easy targets for our ground-attack aircraft.

24th November

At last I get an opportunity to write. Until now it has been impossible as the rate of advance has been so terrific. We have now stopped for a breather before carrying on with the second phase. It will start with the Battle of El Agheila, and I anticipate several days of tough fighting.

Broadhurst is out here. He’s got a very important job as number two to the AOC. He sends you his regards.

Looking back on the past eighteen months I can say I’ve enjoyed it. It’s meant hard work under rather hard conditions, with very infrequent visits to Cairo or Alex when one spends a lot of money and wakes up with an awful head next morning.

All the love in the world my dearest. Look after yourself I love you so much.

The advance westwards continued relentlessly and on 24th January 1943 the 8th Army entered Tripoli. Guy Carter was determined that he and I would be first to land at Castel Benito airfield. When we were reasonably confident that it would be safe to do so, we set off in our Hurricanes only to find to our intense annoyance that a party of war correspondents had beaten us to it!

Tripoli, with its splendid curved promenade, had suffered little damage from our night bombing, the port area having been the main target. An officers’ club was soon set up in a large house in the town centre, and very good it was too. After the monotony of desert rations it seemed like heaven.

Soon after Rommel had been driven out of Libya, General Montgomery paid this tribute to the RAF:

‘On your behalf I have sent a special message to the allied air forces that have co-operated with us. I don’t suppose that any army has ever been supported by such a magnificent striking force. I have always maintained that the 8th Army and the RAF in the Western Desert together constitute one fighting machine and therein lies our strength. ‘

A few months earlier I had been told by the C-in-C of the Middle East Air Force, Sir Arthur Tedder, that on reaching Tripoli I would be posted back to the UK, and it was not long before my posting came through. On 4th February, in the absence of Guy, who was stricken low by a bug, I handed over the group to Group Captain ‘Batchy’ Atcherley, one of the well-known Atcherley twins.

During this period I paid a farewell visit to 3 RAAF Squadron. This was one of the two squadrons escorting me when I failed to get to Tobruk in November 1941. When I landed they were having lunch. Bobby Gibbes, their renowned CO, jumping up on his chair, announced: "The wingco is leaving, give him a cheer." This they did, following up with a special, rather bawdy, rendering of Waltzing Matilda.3 Whilst waiting in Tripoli for a lift back to Cairo, AVM Keith Park, who had been my pre-war station commander at Tangmere and who, with Lord Dowding, had masterminded the RAF operations during the Battle of Britain, came over from Malta (where he had taken over from Hugh Pughe Lloyd) to visit Mary Coningham. He invited me to spend a few days in Malta, before returning to the UK. I felt rather sad saying my goodbyes to the many friends I had made in the desert but I was ready to go.

A Mosquito, piloted by Pete Wykeham, arrived to take me to Malta. I was most impressed with the place, with the people of the island for their resolution in the face of almost continuous bombing and with the efficiency of our forces, both in the air defence of the island and the offensive action taken to stop men and supplies reaching the Axis forces in North Africa. As usual, the hospitality was excellent. After three days the visit came to an end and I was flown back to the Continental Hotel in Cairo.

About 8.00 a.m. on my third morning in Cairo I was surprised to get a phone call from Guy Carter, "Rosie, how are you feeling?" His answer to my reply of "terrible" was to come along with a bottle of Zibib, a potent Egyptian drink similar to Pernod and Arak. It was said that drinking it cleaned your teeth. After a few of these we had breakfast at Groppes, a favourite spot, and then went on to the Gezira Sporting Club for drinks and lunch and a visit to the races. After a few hours rest we were ready for a round of the nightclubs. This programme was repeated daily and nightly for a further four days.

On the seventh and what proved to be my last night in Cairo, I was found in some nightclub and told that there was space for me in a Liberator leaving for the UK in a couple of hours. Swiftly collecting my belongings I rushed to the airfield and with a couple of minutes to spare got on board. I fell asleep immediately on the cold cabin floor. Waking up in the morning, stiff, cold and with a hangover I made my way to the cockpit. There the captain told me that we would soon see Gibraltar.

On leaving the aircraft I was recognised by an old acquaintance of mine, a major in the Devons, who remarked that I could not have arrived on a better day as the Gibraltar Millionaires were again giving a party. Coming on top of the alcoholic few days with Guy in Cairo, this was the last thing I wanted. I craved sleep and more sleep. Nevertheless, I was easily persuaded. I spent the day drinking and eating and drinking again – my stamina must have resulted from nearly two years of deprivation in the desert. Wherever it came from, I certainly needed it as the flight back to the UK was delayed for twenty-four hours and the next day I found myself again at a lunch party, which went on until late afternoon. That night we flew back to the UK, landing in Cornwall early next morning.

Thus came to an end a fascinating part of my life. At the age of twenty-six I had been given a position of high responsibility in the Desert Air Force which had not only been successful but which had provided the blueprint for future army/air force co-operation. Working hand in glove with the 8th Army in Cyrenaica, in spite of the inferiority of our fighters, and in spite of the high casualty rates suffered, mainly as a result of our emphasis on offensive action, the pilots of the Desert Air Force operated with unfailing determination and spirit. And gradually gained ascendancy over the Luftwaffe. They were some of the bravest, cheerful and likeable chaps I have ever known and with whom I have been privileged to serve.

The Desert Air Force was also very well led; the combination of Tedder and Mary Coningham could not have been better. We all looked up to them and especially to Mary who was an excellent tactician and leader. He was also very charming. His staff at Air HQ included George Beamish who, as SASO, was succeeded by Harry Broadhurst. And Tommy Elmhirst, the AOA was a brilliant administrator who stayed with Mary Coningham until the end of the war. I knew him well and much later I gave the address at his memorial service at St. Clement Danes. We middle ranking officers who were younger than our opposite numbers in the army, were encouraged to use initiative, and a general spirit of togetherness prevailed.

But all was not perfect. We were not as well trained in tactical operations as we should have been; our air firing was moderate at best, and our armament of .30 and .50 guns was effective only against aircraft and soft-skinned vehicles. What was even worse was that the performance of our Hurricanes and Tomahawks was second rate compared to that of the Me 109.

Basically, air support should entail the air defence of our own troops from air attacks and assistance to those troops by attacking enemy ground forces. Early on we had concluded that offensive action would be the only sensible method of defence. Trying to get some measure of air superiority became our aim.

In a short article in the 1992 Air Mail, I wrote:

‘Life in the Western Desert fifty years ago was tough and precarious. We had to put up with the extremes of heat and cold, the flies, the sandstorms, the shortage of water, the muddy tea, the almost daily diet of bully beef and lard biscuits, the awful-tasting cigarettes, the fear and the never-ending losses of friends and comrades. Yet, with the passage of time most of us tend to dwell on the brighter side, the camaraderie and the cheerfulness which existed among all ranks, the uplift which came with the arrival of the beer ration, the fun of the squadron parties, the joy of the occasional dip in the sea, the tonic effects of a weekend in Alexandria or Cairo, the sing-songs at Air HQ with Air Vice-Marshal Mary Coningham and Air Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder joining in, the elation of winning, and that great feeling of being alive. ‘

On leaving the desert I was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) the citation for which read:

‘This officer is a brilliant controller and has been second in command of number 211 Group since March 1942. His outstanding personality and great knowledge of operations in the Western Desert were largely responsible for the successful fighting retreat and subsequent advance of the group over an approximate distance of 2,500 miles. Wing Commander Rosier, by his cheerfulness, understanding and popularity with all branches of the service has been a source of inspiration to all with whom he came into contact.’

The author wearing a Grove Park school blazer, 1934.

The author (back row, far right) taken at Bristol Flying School in 1935.

The author’s Hawker Fury, named ‘Queen of North & South’ which he flew between 1936 and 1939.

The author as flight commander of B Flight with an aircraft fitter, taken in 1937.

The author on the right, outside B Flight office of 43 Squadron, Tangmere 1936.

Portrait of the author, taken in 1938, wearing a 43 Squadron tie.

43 Squadron reunion dinner at the Savoy Hotel in April 1937.

Aerobatics in a Fury, 1937.

43 Squadron final squadron formation in Furies, January 1939.

The author and his wife Het on their wedding day, 30th September 1939. There was no time for a wedding dress!

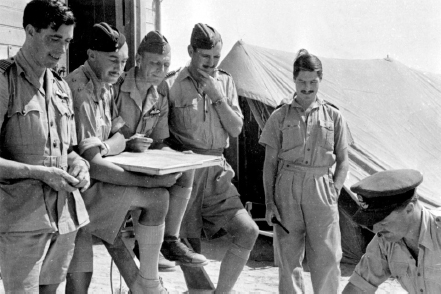

A wing briefing in the Western Desert, 1942.

The author with Wing Commander Pete Wykeham, Western Desert 1942.

Posing in the officers’ mess of 262 Wing, 1942.

211 Fighter Group HQ, Western Desert 1942. (Left to right) Group Captain Guy Carter, AVM Mary Coningham, the author, others unknown.

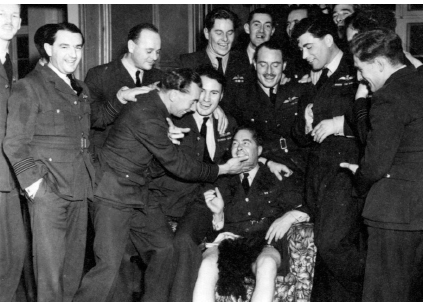

Relaxing in the officers’ mess of 262 Wing, 1942.

Air Vice-Marshal Sir Keith Park, Air Vice-Marshal Mary Coningham, and the author, Tripoli, February 1943.

The author joking with Guy Carter and Mary Coningham, Western Desert 1942.

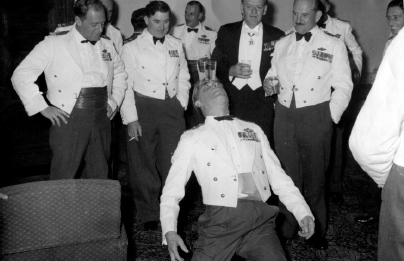

Senior RAF team, Tripoli, February 1943. The author is back row, second from left

The author as group captain at RAF Aston Down, 1943.

Olek Gabszewicz, Polish 131 Wing Leader, and his wife on being awarded Virtuti Militari, Northolt, 1943.

The author inspecting Polish troops, Aston Down 1943.

The author now station commander of RAF Northolt, 1943, wearing Polish flying wings.

Portrait photo of the author taken in 1944, clearly showing his burn scars.

84 Group operations room, 1944.

Visit of HM King George VI to 84 Group HQ, Belgium (the author on the left), October 1944.

General Montgomery visiting 1st Canadian Army (the author far right), autumn 1944.

Portrait of the author by William Dring, 1944.

Devastation caused by bombing raids on a German city, 1945.

Time for celebration! 84 Group, May 1945.

Denys Gillam’s wedding at the Savoy, June 1945. (Left to right) Zulu and Audrey Morris, Al Deere, the author and wife Het, and Joan Deere.

Crowds at the Victory Air Display, taken in The Hague, September 1945.

Victory flypast, The Hague, September 1945.

84 Group summer party, Celle, 1945.

Het presenting Sports Day prizes at Horsham St. Faith, 1947.

The author now station commander at RAF Horsham St. Faith, 1947.

Class photo at the Armed Forces Staff College, Norfolk, Virginia, USA 1948.

The author and his wife, looking glamorous at Mitchell Field, New York, 1949.

The author, now group captain flying, CFE, getting ready for take-off at RAF West Raynham, 1952.

HRH Duke of Edinburgh with the pilots of West Raynham, 1953. The author is second to his left.

The author flying a Desford Trainer in prone position, West Raynham, 1953.

Nicholas’ christening, West Raynham, 1953. Back row centre is ‘Birdy’ Bird-Wilson and second from right is ‘Ricky’ Wright

The author in flying kit at West Raynham, 1953.

The author greeted by son David on his return from a trip to Australia and New Zealand, West Raynham, 1953.

The author getting into his suit before flying a Meteor, West Raynham, 1954.

The author with Ricky Wright, Eglin AFB, Florida, November 1954.

The author playing cricket for Imperial Defence College, Burton Court, 1957.

The author on promotion to air commodore in 1958.

Chiefs of staff, Middle East Command, 1962. Clockwise from back left: Major General Robertson, the author, Rear Admiral Fitzroy Talbot, Air Marshal Sir Charles ‘Sam’ Elworthy (C-in-C), unknown.

The author on becoming ADC to HM The Queen, 1958.

Family photo of the Rosiers taken in 1958. Nicholas and David are at the back, and Lis is seated with her parents.

Group shot at the Chiefs of Staff conference (the author, now director RAF plans is back row, second right), Air Ministry, 1958.

With Air Vice-Marshal Ralph Bentley, AOC Rhodesian Air Force, 1962.

The author performing his ‘party trick’, Aden, 1963.

The author with HM The Queen inspecting Royal Observer Corps, RAF Bentley Priory, 1967.

The author playing the ‘fiddle’ at a party in Aden, 1963.

The author about to fly a Lightning, Fighter Command, 1967.

The author with Sir Robert Watson-Watt, the inventor of radar, at Bawdsey Radar Station, Suffolk, 4th August 1967.

Flypast over the Fighter Command disbandment parade.

Battle of Britain veterans at the disbandment parade of Fighter Command, April 1968. (L to R) Johnnie Johnson, Peter Townsend, Bob Stanford-Tuck, the author, Al Deere, Douglas Bader, Peter Brothers.

The author inspecting Winchester College CCF, son David Rosier, head of the RAF section, is beside him on the left, June 1968.

The author flying a Harrier with Wing Commander Le Brocq, RAF Wildenrath, 9th March 1972.

Group shot taken at the CAS conference, 1973; the author is on the front row 6th from left.

The author unveiling the Polish air force memorial at St. Clement Danes, 1968.

The author, now wing commander, with Group Captain ‘Bing’ Cross, Western Desert 1942.

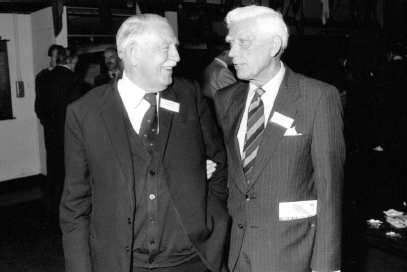

The author again with Air Chief Marshal Sir Kenneth ‘Bing’ Cross, 1992. They haven’t changed a bit!

Flypast over St. Clement Danes by 43 Squadron Tornadoes after the author’s memorial service on 14th December 1998.

The author installed as Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath, Westminster Abbey, 1993.