A NEW CHAPTER IN THE US

USA ARMED FORCES STAFF COLLEGE

JANUARY 1948-July 1948

I can remember little of those few days in Wrexham, but still dominant in my mind are my efforts to sell my car, a large pre-war Vauxhall, and to get rid of everything that seemed unnecessary and cumbersome as I needed some available cash in order to take advantage of what the United States had to offer. I had virtually nothing in my bank account. The miserly war bonus of £190 had disappeared at Horsham where, as station commander in 1947, the entertainment allowance I received was still the pre-war rate of half a crown per day (2/6d – now 12½ pence) and I had had to entertain a lot of visitors. January 1948 proved to be one of the earliest examples of my long line of financial mistakes. I sold my Purdy 12-bore shotgun for £12 and the Vauxhall at a give-away price to a vet who convinced me that it was suitable only for the transportation of sick animals.

I left Het and Elisabeth in Wrexham for a few days whilst I reported to the Air Ministry for briefings from the various departments. I then met them at Paddington on Friday 9th January. Taxis were still not plentiful but I had managed through the RAF Club to get one to take us to Victoria. In the late afternoon we boarded the boat-train to Southampton. At Victoria the hustle and bustle made for an exciting start to our trip.

Ours was one of the earliest post-war Atlantic crossings by The Queen Elizabeth and there was a feeling in the air that once again luxury ocean travel was heralding the revival of British prestige. The ship had been refurbished to the highest standard. It had been reported to be sumptuously elegant and glamorous – with ballrooms and night clubs. Geraldo, the famous band leader, was in overall charge of four or five bands – known as Geraldo’s Army. To travel first class on The Queen Elizabeth was a status symbol highly regarded by Hollywood stars and the rich and famous from both sides of the Atlantic. We in cabin class, who had embarked on the Friday evening, watched with interest as the first class passengers arrived on Saturday morning in a special boat-train made up entirely of first class coaches.

However we did not feel like second-class citizens. Our four-bunk cabin was quite small but well-equipped. We could not believe that when it was a troop ship the same cabin had fifteen bunks. Our steward, who had joined the ship in 1938, had served on her throughout the war. He had been with the first contingent of troops that had been brought from Sydney to the Middle East and Britain. After 1942 she made a number of quick dashes across the Atlantic filled to the gunnels with up to 5,000 American troops. Her final contribution to victory was to transport the quite considerable number of GI brides and children acquired by Americans whilst serving in the UK, to their new homes in the US. (There had been rumours that the two Queens were having their engines removed as these would be supplanted by the 1,000 ‘oars’ on board!)

Our dinner on the first evening exceeded all possible expectations but the most memorable thing was the whiteness of the bread, the like of which we had not seen for many years. Het’s immediate reaction was that she must send a sample of this whiter than white bread to her mother. It would be like the snowdrops, a harbinger of spring, as it promised a future when bread could once again be made from unadulterated flour. In the event, this was not to be until 1954. Interestingly, although bread had not been rationed during the war, it had become so in the early post-war years.

We left Southampton on the Saturday afternoon, steaming slowly along the south coast. At dusk we went on deck to catch our last glimpse of England. Finally, with the lights of the Eddystone Lighthouse disappearing in our wake, we made our way to the dining room where we again marvelled at the sumptuousness of the décor and the quality and variety of food. Het was not to know that this was to be her last meal there. Next morning she was so stricken with sea-sickness that she did not leave the cabin, and rarely her bunk, for the rest of the voyage.

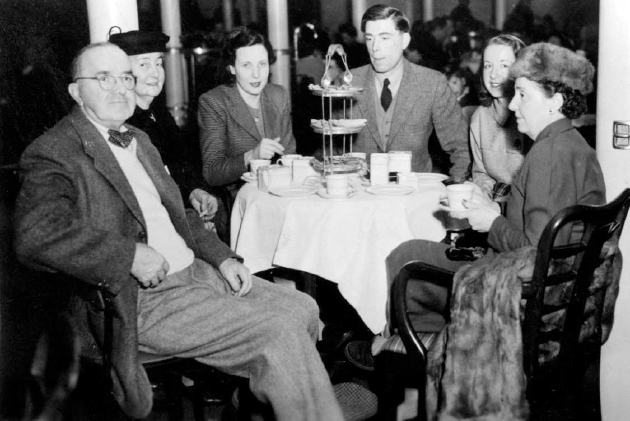

The author and his wife Het taking (her first, and only!) tea on board Queen Elizabeth en route to the USA, January 1948.

Although only just four, Elisabeth made her own way to the nursery every day where she became friends with the six-year-old son of the popular British actor, David Niven. He had remarried just before the ship sailed and was on the Queen Elizabeth honeymooning with his new wife, a Swedish model. We had known his late wife, Primrose, quite well when she was a WAAF officer. She had died in 1946 after falling down the cellar steps at their home in Hollywood.

After enduring a very rough voyage, we at last arrived in New York on the Thursday afternoon. As the ship was not fitted with stabilisers, she was forced to slow down so much that we eventually docked twenty-eight hours late. Noon on that Thursday saw us on deck as the skyline of New York came into view. Seeing the Statue of Liberty I remember wondering about the welcome I would receive from the United States Air Force and how different life would be from that in a still bleak Britain.

We were met by an agent, an American employed by the British Government. His job was to expedite the passage through customs of those diplomats and servicemen taking up posts in the United States. Although he undoubtedly made use of his know-how, it seemed that we waited an inordinately long time in the bitter cold of the open customs sheds. When all business was completed we made our way through swirls of snow to a car in which he chauffeured us through Manhattan’s rush hour traffic en-route to the Governor Clinton Hotel. There I gave him what I considered to be a huge tip. During my briefing in London I had been told how much to tip and had queried the amount, but was advised that this was what must be paid. I did as ordered. I began to understand how things worked in the US.

That evening we ventured out to do some sightseeing but the weather was so bitter that we managed no more than the Empire State Building. There, in the express lift, we were whisked at speed to the thirty-second floor, where we felt compelled to ‘acclimatise’ by having a hamburger and Coca Cola. It was my first and last.

Next morning we realised how many differences, albeit minor, that we were about to encounter. Upon arriving in the dining room for breakfast, we were directed to the coffee shop where our breakfast order consisted of fried eggs, ‘sunny side up’ accompanied by wafer-thin, crispy bacon and buckwheat pancakes with, to our amazement, maple syrup. The next day, sitting on high stools at the counter of the same coffee shop, we learned that if we wanted what we had always known as sausages, we must ask for ‘links’. We also learned that to get what we called bacon we should ask for Canadian bacon. There was a whole new vocabulary to be learned.

For our trip to Washington the next morning we had only to cross the road to the Penn Station terminus of the Pennsylvania railroad. Here again it was an adventure in itself finding our way around this vast, bustling and noisy station as there was intense activity everywhere. Huge engines were belching out steam ready for the off. Red-hatted porters (Red Caps) seemed to be milling around everywhere. Elisabeth, presuming that their skin colour was caused by the smoky atmosphere, asked her mother whether her face was also black. That, at the age of four in 1948, she had never seen a black person, illustrates graphically how great has been the change in the last fifty years from what we used to call ‘Merrie England’ to today’s multi-cultural Britain.

On boarding the train we settled into a superbly furnished Pullman coach, red-curtained and tastefully upholstered with tables and red table lamps. We felt that this was a little ahead of the Great Western Railway on which we had journeyed to Paddington a few days previously.

Our four nights in Washington were spent at the Graylyn Hotel, just off Connecticut Circle. That first night, undeterred by the snow, we walked down an almost deserted Pennsylvania Avenue as far as the floodlit White House. This was an impressive sight, tempered somewhat b y, what seemed to us, a profligate use of electricity. The brightly lit shop windows had been a pleasant surprise. Understandably we were chiefly fascinated by the fully stocked liquor shops and the huge car lots filled to capacity. At home drinks and cars were at the top of our list of shortages.

We then spent Sunday with Zulu Morris, who had been SASO of 84 Group during the campaign in northern Europe, and who was now a student at the US National Defense College. I was to succeed him eighteen years later as commander-in-chief of Fighter Command. On the Monday morning I reported to British Joint Services Mission (BJSM) for further briefings and on the Wednesday evening we set out on the last leg of our journey by taking the overnight ferry to Norfolk, Virginia. When we arrived to embark at Washington’s Fisherman’s Wharf we were somewhat surprised to find that we were to board a rather ancient-looking paddle steamer. It was no doubt adequately equipped for the job but the crunching noises made when we failed to avoid the floating ice blocks did cause us some alarm. However, after clearing the Potomac for the open sea, all was well.

We arrived at the Norfolk naval base at 7.00 a.m. There, awaiting our arrival, was the car we had bought from a British colonel on the previous course who was now safely back in Camberley. What a sad sight; we soon discovered that it was well known in those parts as the Purple Peril. We were very quickly to discover that its mechanical deficiencies did indeed make it perilous.

We set out in the Purple Peril along the coast road to Virginia Beach, about twenty miles away. There we took over a house from my RAF predecessor on No.2 Course. This grey clapboard house was within a few yards of the ocean, overlooking a deserted beach washed by a dull, angry sea. The house itself, usually a summer-only letting, was sparsely furnished and lacking those comforts we had been expecting. This did nothing to lift our spirits. However, our landlords the Halls, who lived close by, were very welcoming. Throughout the whole of our time there they were most helpful and hospitable. They were Southerners through and through with their oft-declared dislike of Yankees and ‘white trash’. During our first week there we had the first fall of snow for forty years; which caused great excitement. The naval base was closed for the first time ever. Much impromptu partying ensued.

With the coming of an early spring only a few weeks later, we knew we were going to love living there. We very much enjoyed the rest of the five months that we lived in that house. Our newly-found American friends loved it too. Living in rather cramped apartments on the naval base, they frequently made a point of getting out to the beach at weekends where they treated our house as their headquarters. With duty-free gin at eight shillings a bottle and a four-bushel sack of oysters costing five shillings, we could afford to entertain lavishly. However, they never could understand how or why we drank hot tea even when the temperature was in the 80s.

Virginia Beach was a fashionable resort dominated by the Cavalier Hotel built at the turn of the century by a railway millionaire. This, and the town itself, were ‘restricted’. It was some time before I learned that this meant that no Jews were allowed there. Garden City on Long Island, where we lived later, was similarly restricted. This was in 1948 in the ‘Land of the Free’.

Elisabeth went to Mrs Everett’s, a private school. There she quickly learned much that no doubt helped later when she became an American citizen. Returning home on her second day, she asked her mother if she knew that George Washington was our first president. She was far from popular when Pearl Harbor was mentioned and she told her teacher that her daddy said: “Pearl Harbor was where the Americans were caught with their pants down!”

My day started early as, in order to get to the Armed Forces Staff College by 8.00 a.m., I had to leave at 6.15 as Virginia Beach was in a different time zone. Our work, consisting of lectures, exercises and visits, was taken fairly light-heartedly by the four British officers there. In addition to the 100 US students, there were also three Canadians. We seven made up some sort of opposition, united in argument. The Americans treated the course far more seriously than we did. They had more to lose! They diligently read all the set books. We did not. At the end of June however we all graduated and received our ‘sheepskins’.

For us the social activities were the highlight of the course. We never missed the weekly Friday night dances. There we heard for the first time many of the ‘state songs’, such as The Eyes of Texas are Upon You, Way Back in Indiana and The Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. The last dance was always Bongo, Bongo, Bongo, I Don’t Want to Leave the Congo. We certainly had fun.

In celebration of the silver wedding of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, the British and Canadian contingent, with the help of our duty-free allowances, gave a party for about 100 people. This was regarded as the social highlight of the course. Invitations were eagerly sought after. Most of the American women bought new dresses for what they insisted on calling ‘The Silvo Wedding’.

We made several lifelong friends at the staff college with whom we got together whenever we went to the States and whenever they were assigned to Europe. Amongst these was Davy Jones who arrived in Norfolk in 1951 to command the newly-opened USAF bomber base at Sculthorpe on the very same day that I arrived to be group captain flying at the Central Fighter Establishment at West Raynham five miles away. In 1968 when I was C-in-C Fighter Command, Het and I and a team from the headquarters visited him in Florida where he was the general in charge of the rocket base there. Throughout his career he was known as ‘Tokyo Jones’ as he had been on the Dolittle Raid in 1942, made famous by the order: “Fly there, find your own way home.”

Another was Frank Murdoch who had married Denny in 1944 in Hampshire, where he was stationed prior to D-Day. She was the widow of a pilot killed in action in August 1940, a few weeks before their daughter was born. Her brother, Peter Powell, whom I knew well, had also flown in the Battle of Britain. She was a great-niece of Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scout Movement. Denny made herself known to us at the ‘welcome reception’ where we had the new experience of being greeted and passed down the line of thirteen generals and their wives.

We stayed with the Murdochs in Paris in l956 and Verona in 1965 and also, following his retirement as a brigadier general, on their farm near Roanoke, Virginia where he was rearing and training horses, helped by two horse-mad daughters. All of his family of one son and four daughters had inherited his skill and interest in horses. He had been in the US riding team in the 1948 Olympics and a member of the 7th Cavalry before the war and before mechanisation. In 1950 we had accompanied the Murdochs to West Point for Frank’s fifteenth class reunion. There I was made an honorary member of the 7th Cavalry. I was to work with a number of them later in NATO and in particular in CENTO where in Ankara in 1970 there were three generals who were all former 7th Cavalry officers.

When the course ended in early July we went our separate ways. I was posted to Continental Air Command (ConAC). ConAC, under General George Stratemeyer, and based at Mitchel Air Force Base ‘Mitchell Field’ on Long Island just outside New York, was tasked with establishing an Air Defense Command. At the time General Gordon Seville, who was shortly to be followed by General Bob Webster, was in charge of Eastern Air Defense Force. As a result of their efforts, Air Defense Command was finally established in 1951. Then, under General Ennis Whitehead (‘Ennis the Menace’), it moved to Colorado Springs where, playing a vital part in the US security, it has remained to this day.

I had been given the choice of going to Mitchel or to the Tactical Air Force Headquarters at Langley Field. Having worked in the tactical world since 1941, I thought it time for a change. The Berlin Air Lift, which was taking place at this time, made me aware that in the further necessary developments of air defence, there would be much interesting work.

We left Virginia Beach, taking the ferry across to Cape Henry, and drove to New York overnight. Hampton Roads, which abounded with ferries in those days, is now criss-crossed with long, high bridges. However we were not in the Purple Peril which had lasted less than a month. There was general agreement that I had been conned; yet another financial mistake! With our meagre dollar allowance the necessary purchase of another car had been difficult. Finally, we had acquired a brand-new Austin A40. Unfortunately this was another financial disaster. I had paid for it at four dollars to the pound two days before Sir Stafford Cripps devalued the pound to two dollars-eighty cents, despite his constant assurances that he would never do so. This confirmed my opinion about politicians.

MITCHELL FIELD, LONG ISLAND

JULY 1948-JUNE 1950

On reporting for duty at ConAC HQ I found I was assigned to research evaluation which suited me well. However, although everyone in the office was welcoming and friendly, I quickly became aware that I was simply marking time. No work of any importance was passed to me. Papers marked ‘secret’ by-passed me completely. After six weeks of having virtually nothing to do, I asked to see the general. I explained to him that as I could see no point in wasting my time there, I was about to write to Tedder, then CAS, to ask for my recall. This would obviously reflect badly on the much-heralded exchange programme just introduced between the two air forces. The general apparently got on to the Pentagon straight away and I was told the very next afternoon that I was ‘fully cleared’. From then on I was to take part in every aspect of the development of Air Defense Command.

We were an enthusiastic bunch. We travelled widely mostly flying ourselves. As a result, during my time at Mitchell Field I qualified to fly the F80, the F84 and F86, the B25 and B26 and the C47. We made frequent visits to Boston where, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), a department had been set up solely for the development of air defence. We regularly visited aircraft factories, most of which were situated on the West Coast; I must have made half a dozen trips to Lockheeds in California and we visited USAF bases all over the US. Little did I think on my visits to Coco Beach in Florida that it would develop into Cape Canaveral and the Kennedy Space Center. Nor did I imagine that, when we attended the official opening of the small Idlewild Airport nearby on Long Island, it would eventually become New York’s Kennedy Airport.

There were lighter sides to our ‘business trips’. We would fly up to Maine with the sole object of bringing back lobsters for pre-arranged office lobster suppers. On one trip my co-pilot, Colonel Cary, and I found time to fly the length of the Grand Canyon. With some luck we managed to be in Indianapolis for their annual motor racing bonanza, the Indianapolis 500. The fact that the USAF worked on a system known as ‘cutting your own orders’ was a great help. I can remember that only once was a trip cancelled because there was nothing left in the budget that month.

During my tour I spent a few days flying F84s as a member of a fighter squadron at Otis Field, Cape Cod and at Selfridge Field near Detroit. I even gave a lecture on air defence at the Air University at Maxwell Field, Montgomery, Alabama.

At that time great changes were taking place as the USAF had become a separate service and was no longer the US Army Air Force. Although very keen on this development, the officers were reluctant to give up their old, fine quality, gabardine uniforms. They disliked the blue lightweight material of what they deemed a badly designed new uniform. They loved their ‘olives’ and their ‘pinks’ which they mixed and matched at will. It was inevitable that the wearing of the new uniform would become compulsory. When we left in June 1950 all were wearing blue.

The order for racial integration was put into effect at that time. This resulted in three very smartly dressed wives of three black officers turning up at the officers’ club for the first time in February 1949 for a Valentine’s Day lunch, which it so happened was being hosted by the wives of ‘our’ office. Consternation reigned. After a ‘pow-wow’ Het was allowed to talk to them, but on no account was she to introduce them to anyone else. That, unbelievably, was the state of things in the US in 1949.

On my many visits to the US Air Force since then I have observed the great progress that has been made in this area. I have always thought what brave pioneers those three wives were. Het never fails to remind me that at that time in the UK women were not allowed into the RAF Club through the main door in Piccadilly. They had to enter through a door in a side street which was especially reserved for women and for officers’ baggage!

I was determined that we should see as much as possible of the US. Whenever I went on attachments to fighter squadrons Het and Elisabeth came too. We had ten days at Otis Field on Cape Cod when I was attached to a F84 squadron. There, we were able to explore and take part in the activities of this fashionable holiday playground. We visited the summer theatres which flourished there and saw a New York production of ‘The Second Mrs Tanqueray’. Playing the lead was a very well known actress, Tallulah Bankhead.

Het and Lis also came on my attachment to an F84 squadron at Sel-fridge Field, near Detroit, from where we went on to Toronto and came home via Niagara Falls. We had previously been on two other Canadian trips to Montreal and Ottawa. Compared with the USA, Canada seemed terribly old-fashioned. Forgetting about Britain, we found it hard to believe that there were places where shops still closed at noon on Saturday! However, in Canada we felt at home again. Everywhere there were posters stating ‘Buy British’ and ‘British is Best’.

In the summer of l949 I returned to England for a few days to attend the annual ‘fighter tactical convention’ at the Central Fighter Establishment at West Raynham. There I met many old friends.

That autumn we drove to Boston along the Maple Leaf Trail. In winter we skied in the Adirondacks in upstate New York and we made frequent trips to nearby Coney Island in the summer. We also got to know New York City very well. We went to Carnegie Hall a number of times and at the Metropolitan Opera House saw Margot Fontaine appearing with the Royal Ballet on its first overseas tour.

We were lucky to attend a New York ‘society wedding’. A poverty-stricken friend of mine, Wing Commander Hedley Cliff, was marrying Tucky Astor. In 1949 she held the record for having received a one million dollar alimony settlement. The champagne flowed very freely at the reception during which Het was admonished by Tucky’s cousin Gloria, then in her eighties, because the new British Ambassador, Sir Oliver Franks, had been in the US for a month but had not yet called on her. Het made the excuse that he was only forty-two, thus inferring that he had a lot to learn and no doubt wisdom would come with age. This excuse was dismissed by Gloria Astor. And Het felt that the only way to hold her own was to refuse Gloria’s invitation to have tea with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor on the following Sunday afternoon, as ‘she had a previous luncheon engagement’. I knew nothing of this until the next morning when she shot up in bed and told me that we had refused to have tea with the Windsors. She warned me that I was not to tell anyone, especially our lunch guests the Ashkins! Of course I did. Nearly fifty years later, whilst staying with them in Santa Barbara, California, they still remembered this incident and told us that they had wondered if we were quite sane. No doubt this is the reason that we got on so well. Jane Ashkins became David’s godmother.

In April 1950 I took three weeks leave with the sole purpose of seeing more of the States. I was conscious of the fact that Het had not seen as much of the country as I had. Unfortunately, we had neither the time nor money to go further west than New Orleans. We started by driving through the Carolinas to the Deep South where, in the acres and acres of cotton fields, the cotton was still being picked by hand.

In New Orleans we did all that tourists were expected to do. We had dinner at Antoines, where we ate Oysters Rockefeller. We then made our way from one end to the other of Basin Street listening to a variety of bands playing jazz and the blues.

From New Orleans we made our way along the Gulf coast of Florida where we stayed for a few days at Sarasota. It was then a village comprised almost entirely of the winter quarters of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus. At the Ringling Hotel, where we were staying, we met a number of the performers. When Het arrived from putting Elisabeth to bed she was surprised to find me chatting at the bar with Bette Davis. She managed to whisper to me, but the name meant nothing.

We were welcomed heartily by a brother and sister acrobatic team from the circus. Despite the broadest of Yorkshire accents, having been born near Sheffield, they were known as the ‘Great Alanzas’. They kept their promise to invite us to Madison Square Garden when the circus opened in New York. We were most impressed by their very daring performance and appreciated their kindness in inviting us backstage

After Sarasota we decided to return to Long Island by driving up the Atlantic coast. This entailed crossing the Everglades to Miami. In those days this was regarded as quite an adventurous trip as it was not until some time later that the Everglades were opened up as a tourist attraction. As Miami did not appeal to us, we stayed at a small village a few miles to the north. Returning there forty years on we marvelled how it had grown into Fort Lauderdale, the starting point or port of call for most Caribbean cruises.

The next morning we drove further north to Daytona Beach where we spent a week. We were attracted by the long stretch of silver sands where the British driver, Sir Henry Segrave, had broken the world land-speed record in 1927. Thirty years later, whenever we stayed with Elisabeth and her husband who was working at the Space Center in Florida, we always paid Daytona a nostalgic visit. Driving on the beach is still permitted to the general public.

Within ten days of returning to Mitchell Field I was told that my tour had been curtailed. I had been posted to the directing staff of the Joint Services Staff College at Latimer in Buckinghamshire. My superiors thought that I should get to know the ropes by reporting there for the last few weeks of the current course, which ended in late July. After that I could have my disembarkation leave until the next course began in early September.

On 31st May I was told that we would be leaving on Saturday 10th June on the Cunard liner, the Caronia. Panic ensued. There was much to be done as we had not yet purchased many of the goods that we wanted which were not obtainable back in Britain. Our American friends panicked too. Every single night we attended farewell parties. At one, neither Het nor I could recollect ever having previously met the hosts. Obviously any excuse for a party!

After ten hectic days of shopping, which also involved some ‘weight guessing’, came the fateful day. The weight guessing was necessary because of the constant reminder from BJSM (British Joint Services Mission), Washington that if we had goods in excess of a wing commander’s weight allowance we would have to pay for them. I recognise now how foolish we must have seemed to the salesman who was selling us a washing machine. We insisted on lifting the various machines and bought the one we judged to be the lightest, not the one that we thought was probably the best.

At about 10.00 a.m. on the day we were due to leave, a motorcade of five cars turned up to take us to Pier 9D on Manhattan Island. On boarding the Caronia about twenty people, including my commanding general, General Webster, and his wife, squeezed into our cabin for a cheerful farewell party. Het missed more of the party than she had bargained for. She had deemed it her motherly duty to take Elisabeth to the Empire State Building for a final viewing of New York. Our cabin jollifications had gone on for some time before I realised that my wife and daughter were missing. I left immediately in search of them. It transpired that the flight sergeant with whom I had entrusted their boarding passes had failed to recognise Het in the smart new hat that she had not been able to resist buying on her way to the ship. As a result she had been waiting on the dock for an hour and was so angry that she threatened not to return to the UK with me. I thought it most unfair as she was the one who had bought the hat!

At 2.30 p.m. we weighed anchor. The owners of the tugs operating in New York harbour were the Gillans, friends who lived near us at Rockville Center, Long Island. They had warned us that the tug masters had been told that when casting the Caronia free they were to give three farewell toots rather than the usual two. Apparently three toots were given only when VIPs were on board. Meanwhile our friends had rushed to the Staten Island ferry. As we sailed past the Statue of Liberty we glimpsed them waving until we disappeared from sight.

After our hectic final few days we were ready to relax on what was virtually to be a seven-day summer cruise. I was delighted to find an old friend, Tubby Butler, on board who was returning from a two-year posting at the Pentagon. He was later to command the Parachute Brigade at Suez and later still became a four-star general. He was excellent company although his behaviour was somewhat unorthodox! His notoriety stemmed from the fact that before the war, whilst serving as an ADC, he had eloped with his general’s wife. He had been forced to leave the army but at the start of the war had rejoined as a private soldier. All was forgiven by the authorities but not, I believe, by the general himself. He was re-commissioned and, when the general agreed to a divorce in 1941, married the general’s former wife. She and her eighteen-year-old daughter were with him. With his usual charm and Irish blarney he soon made his mark with the head barman. As a result he volunteered to introduce us to the customs officer when he came aboard from his launch before we docked at Southampton on the Saturday morning.

We were duly introduced and after a drink or two he got down to business. We answered all questions in line with his promptings. He returned with us to our cabins, put some chalk squiggles on our luggage and finally gave us instructions concerning the number of the customs desk that we were to use. There we were charged £3 for all the goods we had accumulated during our two-year stay in the United States which included a smart fur jacket, a washing machine, a waffle iron, some long-playing records that were not available in the UK, and about a dozen pairs of nylon stockings which were available but not easily obtainable.

It had been our intention to drive away in my Austin A40 which had accompanied us on the Caronia. However, we took a rather jaundiced view of our motherland when we were told by customs that, as it was nearing noon, it was too late to contact my bank to find out whether my cheque to the car licensing authorities could be met. Despite my protestations, we were told to return on Monday at 11.00 a.m. We therefore spent the weekend at our friends the McEvoys at Kenley, where Mac was the AOC of a flying training group. On the Monday morning, having collected our car, we left for North Wales where Het and Lis stayed for the next two months. Since leaving in January 1948 we had lived in five houses and Elisabeth had attended three schools.