Chapter 13

High Achievers and Fine Minds

The men, of course, have their Rhodes Scholarships, but there is nothing for the women.

—Dorothea Sharp, 1924 scholarship winner1

The Travelling Scholarship was one of the first initiatives undertaken by the new federation and local clubs soon followed suit with undergraduate awards. Over the years more awards were added, creating one of the most costly, and the most highly prized, of all CFUW programs. In the absence of women-only scholarships and in recognition of the barriers—both formal and informal—against women being able to access mainstream academic funding, the CFUW scholarships, later called fellowships, for advanced study gave women a foothold of sorts into the realm of higher education. In spite of this, women continued to face many obstacles and, in the federation’s view, too few of them gained the academic positions they sought. Despite their struggles, most of these women made stellar research and teaching contributions in numerous fields; some of them became loyal and hardworking members of CFUW clubs and a few volunteered at the federal level. While the careers of some of these women, scientists in particular, have received some scholarly attention, most of the recipients remain largely unknown.2 The following exploration of their lives—as much as the sources allow—provides a glimpse into the achievements of some exceptional young women. Proud of their accomplishments, the federation tried to keep track of their successes, at least until the early post-World War II era. One of the first tasks the new federation archivist completed in the early 1920s was to conduct a survey of the educational pioneers who had fought for the right to attend university, many of whom became CFUW members. After that, the federation began publishing regular updates on scholarship winners in the Chronicle in order to keep their members—the very people who supported the program through their membership dues—informed. While a collective biography of the scholarship winners, which remains a good idea, was contemplated several times, this has not yet come to fruition.

The Travelling Scholarship supported overseas study because Canadian universities, some still relatively new, lacked the same prestige that those in Britain and Europe enjoyed. As well, the federation, as a new member of the International Federation of University Women (IFUW), joined their compatriots in seeking international exchanges to further understanding among the nations of the world and to promote peace. Thus, early scholarship winners almost invariably travelled to Europe or to England to study, although during World War II many of them attended universities in the United States. The federation’s stringent selection criteria were based on a candidate’s ability, promise of research, and character. The Scholarship Committee sought candidates with at least an MA and often a partially completed PhD, and had several times rejected suggestions that financial need be considered. Thus, rather than disqualifying a candidate for winning another award, the federation was proud that many of its recipients had won prizes in other competitions. The committee felt that this reinforced their choices. The range of study areas among applicants was broad. While many scholars were working in the more traditional fields for women such as literature, languages, classics, and history, and even natural sciences such as biology and botany, where women had developed a solid track record as gifted amateurs, the organization showed a slight preference for women working in science and in non-

traditional subjects. By 1938, for example, of the eighteen women who had won CFUW Travelling Scholarships, ten were in the humanities and eight were in science, four of them studying biology. Later, the social sciences such as psychology, sociology, and political science would figure prominently.

Scholarship committees, tasked with the selection of scholarship winners, were continually delighted with the number of well-qualified applicants that came forward. Despite the economic downturn in the 1930s, for instance, University of Alberta classics professor Geneva Misener, reported that Canadian universities were producing “more and more women with the gift and love of learning.”3 The number of applicants rose from eleven in 1928 to twenty-two in 1931. Committee members frequently expressed regret at the number of applicants who had to be turned away and, when finances permitted, they added new scholarships. A Junior Scholarship to assist students who were exceptional but not as far advanced in their studies as the Travelling Scholarship applicants became a reality in 1940.

Interestingly, the initial Junior Scholarship that went to Dorothy Lefevre of Saskatchewan marked the first time that household science (nutrition) was recognized as worthy of support. The 1942 winner, Helen Stewart, assessed the scholarship’s value to her by saying, “the most difficult step financially in postgraduate work is the first year of graduate study. After that, assistantships and fellowships are more easily available.” Thus, she concluded “Your Junior Scholarship is of particular value, and I am very grateful to have been one of its recipients.”4

Applicants were invariably exemplary in their academic achievements. In 1921, the first Travelling Scholarship winner, Isobel Jones, was a 1917 University of Toronto graduate with first-class honours in Greek, Latin, English, and history, who then obtained an MA in English. While teaching at the University of Saskatchewan, however, she discovered that history was her true passion. Typical of most candidates that the committee chose, she had good social and leadership skills and had shown great initiative in learning to type to put herself through school. She used her scholarship to go to France to study the early French period of Canadian history. In her case, as in others in this period, the issue of marriage arose when she married Spanish historian Raymonde Foulché-Delrose before her scholarship was completed and changed her thesis topic from French to Spanish history. In 1928, the committee had decided upon Ellen Hemmeon as the winner, but she soon announced her upcoming marriage. The committee was uncertain how to proceed and the executive eventually decided they could not rescind the award. With apparent relief, they noted that Hemmeon herself had concluded that she could not accept, and the scholarship went instead to E. Beatrice Abbott, a teacher at the Ottawa Ladies’ College. After its 1928–1929 report, the Scholarship Committee raised the question of “whether we should not require that candidates give us some assurance that they will continue their studies until they obtained the desired degree for which they sought the assistance of the scholarship.”5 This was incorporated into the terms of the scholarship program. The committee noted that the only alternative would be to “support the continuance of married women in their posts,” but that most educational institutions would not permit this.

The trend soon shifted to combining marriage and study. Phyllis Gregory, the 1927 winner, attained a bachelor’s degree in economics and political science from the University of British Columbia (UBC) and an MA from Bryn Mawr College before using her scholarship to study at the London School of Economics. While she was in England she married Leonard Turner but continued her studies and became one of CFUW’s many success stories. After she was widowed, she returned to Canada—now as Phyllis Gregory Turner—where she became chief research economist of the Canadian tariff board during the Depression, served on the Dominion Trade and Industry Commission, and was an economic advisor to the Wartime Prices and Trade Board. Credited as “an outstanding administrator and a major force in the direction of Canada’s wartime economy,”6 Gregory nonetheless received only two-thirds of a man’s salary. After moving to British Columbia, she became the first female chancellor of UBC. Her son, John Turner, became Canada’s seventeenth prime minister.

Active in the Ottawa Club, Turner showed great loyalty to the federation. Isobel Jones, even though she had left to marry, came back to volunteer with her club after her husband’s death. In 1936, she lived in Québec and conducted research into French Canada’s history.7 Doris Saunders, the 1925 winner, became CFUW president in the 1950s, and Dr. Margaret Cameron, the 1923 winner, was a lifelong CFUW member. Having studied at the Sorbonne, she lectured in the French department at Smith College and earned a docteur de l’université de Paris in nineteenth-century comparative literature. She then left briefly for the United States, but ultimately found a home at the University of Saskatchewan, where she taught for many years.

The Scholarship Committee expressed concern over losing scholars to the United States—where the large number of women’s colleges afforded more job opportunities for women—and tried to find places for returning scholars in Canadian universities. The 1922 scholarship winner, Dixie Pelluet, an amateur naturalist who had gotten her start collecting specimens in the Rocky Mountains with her father, went to University College, London and in 1927, earned a PhD at Bryn Mawr College.8 She then lectured at Rockford College, Illinois and headed the biology department at Teachers College, Kentucky. A leading scholar in fish embryology, Pelluet was also assertive with regard to her position as a female academic. Before accepting a position at Dalhousie University in 1931, which was offered to her for $2,200, she asked for and received $2,600. When she was set to marry fellow zoologist Ronald Hayes, Pelluet extracted a promise from Dalhousie president Carleton Stanley, that she could keep her job after the wedding.9 Stanley agreed but her salary was frozen. The couple earned honorary doctorates of law from Dalhousie, which created the Ron Hayes and Dixie Pelluet Bursary in biochemistry and molecular biology. Dixie Pelluet Hayes became a full professor only three months before her retirement in 1964, but her late career protests led to a ban on married women faculty members at Dalhousie.10 Not the legacy that she—or the federation—would have hoped for.

Another CFUW scholarship winner who was financially handicapped by her marriage was botanist Silver Dowding, the 1928 winner of the Travelling Scholarship, who was forced to stay on the margins of her field. She earned a Master of Science degree at the University of Alberta, spent a year at Birkbeck College, London, and completed her PhD in 1931 at the University of Manitoba. She worked briefly as a research assistant at the Dominion Experimental Farm in Edmonton and taught at the University of Alberta without salary because she was married to mathematics professor Ernest Sydney Keeping. She made significant contributions to scholarship as associate editor of the Canadian Journal of Microbiology and created a diagnostic service in association with the Alberta provincial laboratory of public health and faculty of medicine. The University of Alberta claims that the lab was the first in the British Commonwealth to collect medically important fungi.11

Dorothea Sharp took a long time to gain an academic post. With the help of her 1924 scholarship she earned her doctorate from Oxford’s Somerville College in 1928.12 A year later she expressed regret that there were so few scholarships open to women in Canada and cautioned that one year was not enough time to complete a research project. She added that the amount was insufficient to cover the high fees in the expensive English tutoring system. Aware of such concerns, the committee nonetheless kept the scholarship as a one-year program in the hopes of spreading their limited financial resources among many women. In 1929, they also voted to create a loan program to help candidates fund a second year. In addition, the federation helped Sharp find alternate funding to complete her research. The Chronicle later noted that Sharp’s thesis, Franciscan Philosophy at Oxford in the Thirteenth Century had been published and, in 1949, announced that she was teaching Greek and medieval political ideas at the London School of Economics. During the war, she was principal in the ministry of health in England, responsible for maternity and child welfare. When she was asked about her publications she answered candidly, “During the war years I worked a 7-day week of usually 14 hours a day and since the war every spare moment from work has had to be devoted to house and food hunting.”13

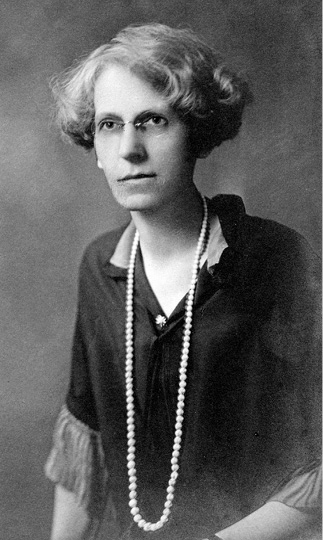

Alice E. Wilson, who received the 1926 Travelling Scholarship, is not only noteworthy for her contribution to science, but also for her creation of a new CFUW award in 1964. As mentioned in a previous chapter, her experience also pushed the organization to advocate for women in the civil service. As a child, Wilson had enjoyed exploring rock formations on canoe trips with her father and brothers but she followed gender conventions in studying languages and history at Victoria College and expected to have a teaching career. She did not like languages, however, and after an illness, took a job at the University of Toronto Museum.14 In 1909, she joined the staff of the Geological Survey of Canada in Ottawa as a clerk, cataloguing limestone specimens containing million-year-old fossils. She finished her degree and in 1911 was appointed to a permanent position on the survey’s technical staff. By the end of World War I, she was an assistant paleontologist. Excluded from all-male survey parties, she was determined to undertake field research and recruited a recent graduate, Madeline Fritz, to accompany her. Travelling on foot and by canoe, they explored comparable varieties of limestone in the Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipeg areas. Fritz later had a distinguished career as a paleontologist at the Royal Ontario Museum and the University of Toronto.

Alice E. Wilson, 1926 Travelling Scholarship winner.

Wishing to pursue further research, Wilson asked for educational leave from the Geological Survey, but, despite her supervisor’s praise and the fact that she was handling responsibilities well above her job classification, she was repeatedly refused. Even after winning the CFUW Travelling Scholarship in 1926, her employer placed numerous obstacles in her path. But she persevered and, with the intervention of CFUW, was granted leave from her position to study and earn a doctorate in geology and paleontology from the University of Chicago in 1929. Over the course of her career, Wilson wrote more than twenty-five scientific publications, produced geological maps of the St. Lawrence Lowlands between Montréal and Kingston, and named more than sixty new fossil taxa (biological classifications). She also wrote a children’s book called The Earth Beneath Our Feet to bring geology to a wider readership.

E. Marie Hearne Creech, 1935 Travelling Scholarship winner.

Alice Wilson, who could often be seen exploring the Ottawa area on foot, by bike, and, later, by car, became the first female fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1938. She was forced to retire from the Geological Survey in 1948, when she turned sixty-five but continued to work at her office until just months before her death. An inspired teacher, she lectured at Carleton College (Carleton University after 1952), which awarded her an honorary doctorate in 1960. In 1952, the Ottawa Club, of which she was a long-standing member, began awarding an annual scholarship to a Carleton student in her name.15 She looked upon the CFUW scholarship as a trust to be returned with interest and bequeathed $1,500 from her modest estate to the federation to create “grants-in-aid” to a maximum of $500 for CFUW members who wished to upgrade their education. Following her death on April 15, 1964, the federation thus created the Alice E. Wilson fellowship. In 2019, this fellowship offered four awards of $5,000 each and an additional two awards of the same value to mark the organization’s 100 anniversary.

By 1930, when the Chronicle first reported on winners’ careers, the obstacles women faced had worsened due to the Depression. While four women among the 1920s winners had already attained professorships and another did so after waiting until 1948, only one among the 1930s recipients found the same success and many of them took teaching jobs at girls’ academies. Lillian Hunter undertook research into plant pathology under the University of Toronto’s Dr. H. S. Jackson, but it was only when she was granted research leave at Harvard Laboratories through Radcliffe College that she was able to work on her topic of plant rusts other than on evenings and weekends. After earning the CFUW scholarship in 1932, she had to delay taking it up because the University of Toronto’s botany department, where she worked as an assistant, refused to give her a year’s leave. The records show later that she was teaching at Moulton Ladies College in Toronto, then a girls’ academy and now a centre for music.

In 1935, Marie Hearne Creech became the first woman with a completed PhD to receive the Travelling Scholarship. With a 1930 MA from Queen’s and a 1933 PhD from McGill, she used her scholarship to study genetics at Strangeways Laboratory in Cambridge, England. While she was there, she married her fellow scientist and collaborator, Hugh J. Creech. As many women were now doing, she refused to choose between her career and her marriage. She was later reported to be researching carcinogenic substances in tissue culture as a research assistant at the Banting Institute in Toronto.16

Like Wilson in 1926, the 1937 winner, Gwendolyn Toby, first studied modern languages at the University of Alberta but later branched into biochemistry. Working with Drs. James Collip of insulin fame and David Thompson at McGill, she became a demonstrator and published her work on adrenal insufficiency. As with many women who had been first channelled into the humanities, her references made a virtue of necessity by speaking of the happy combination “of a fine critical and scientific mind and a broadly human personality.”17 Jobs opened up during the war, and Toby worked with Dr. Collip on sensitive war-related research for the National Research Council (NRC) subcommittee on shock and blood substitutes; their work contributed to the World War II technologies that improved the survival rate of wounded soldiers.18

Constance MacFarlane, 1933 Travelling Scholarship winner.

Constance MacFarlane used her 1933 scholarship to study marine algae at the Liverpool Biological Station, University of Liverpool. A Dalhousie graduate from Prince Edward Island, she had also studied at the University of Toronto and, following her scholarship year, she taught at Branksome Hall in Toronto and Mount Allison School for Girls in Sackville, New Brunswick. MacFarlane contributed substantial research and publications to her field and, from 1949 to 1970, she was director of the seaweeds division of the Nova Scotia Research Foundation. She also taught one course at Acadia.19 Phyllis Brewster, the 1939 winner from Vancouver, had a BSc in pharmacy from the University of Alberta and a MSc from the University of Minnesota. Working in industry, she became the chief chemist of the penicillin pilot plant for Hyland Laboratories until she was forced to take leave because of her husband’s transfer to San Francisco.20

Mary White, a Queen’s University classics scholar, used her 1930 award to study at St Hugh’s College, Oxford. She began her career, like many academic women, teaching at girls’ schools including Moulton Ladies’ College in Toronto. But she persevered, taking advantage of wartime and postwar openings, and was appointed chair of the department of classics at the University of Toronto in 1953.21 In 1931, Dorothy Blakey of UBC and the University of Toronto used her funding to study Wordsworth and the romantic period of English literature at the University of London and was appointed assistant professor of English at UBC. She published The Minerva Press, 1790–1820, a book on the late eighteenth-century and early-nineteenth-century publishing house noted for its sentimental and Gothic fiction, in 1939.

Mary E. White, 1930 Travelling Scholarship winner.

Marion Mitchell Spector, a UBC graduate, was working as a teacher and spending her vacations at the Dominion Archives when she discovered previously untouched records of the Colonial Department in London and used her 1934 scholarship to produce a thesis on the American Revolution. She married Russian historian Ivar Spector from the University of Washington in 1937, and the Chronicle reported that she planned to continue her research, and, “we may rest assured that she is not lost to the army of intellectual workers….”22 By 1940, she was taking an active role in the Seattle American Association of University Women (AAUW) and had her thesis published in the series Columbia Studies in History, Economics and Public Law. During the war, having just published her second book on the American Revolutionary War for which she won an award from the American Historical Association, Spector became a historian at the Seattle army service forces depot.

During the war years, the number of applications increased and the applicants were younger, perhaps reflecting greater opportunities for graduate study. The winners seemed to be predominantly in non-traditional fields and may have been chosen for their potential to contribute to the war effort. The number of BSc degrees earned every year by women in Canada jumped from fifty-one in 1941 to ninety in 1945. Similarly, the percentage of women graduating as physicians jumped from 4.4 per cent to 7.9 per cent.23 As women often applied for more than one scholarship, a kind of “musical chairs” sometimes ensued. In 1948, for example, the Travelling Scholarship was awarded to Enid G. Goldstine of Winnipeg, who had originally been awarded the Junior Scholarship to study French at the University of Paris, but, when the first and second choices turned down the Travelling Scholarship in favour of the Royal Society fellowship of a higher value, the award went to Goldstine.

The federation funded a number of women in the 1940s who contributed to the war effort. Jeanne Starrett Le Caine, the 1940 winner, studied mathematics and economics at Queen’s and Radcliffe before taking a leave of absence from Smith College to work for the Military Research Council in Ottawa. Barbara Underhill from UBC, who had degrees in chemistry and physics from the University of Toronto, studied astrophysics and was appointed to the National Research Council in Montréal. Anne H. Sedgewick, who won the Marty Memorial Scholarship at Queen’s University in 1940 and the CFUW Travelling Scholarship in 1941, took time off from her studies to work with the research section of the Commodity Prices Stabilization Corporation, the subsidy-paying agent of the WPTB. There she served as assistant to the economist Irene Spry. Cathleen Synge, who later married Herbert Moravetz, won the Junior Scholarship in 1945 to study mathematical theory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Barbara Mary St. George Craig, a French student from Queen’s who had won a scholarship from the French government and studied at Bryn Mawr, worked in the Censorship Department in Ottawa during the war, and then taught at Mount Royal College in Calgary before winning the Travelling Scholarship in 1946–1947.24

A few outstanding winners such as 1949 Travelling Scholarship recipient, Carol Evelyn Hopkins, did find university appointments. Hopkins who had won, as an undergraduate, seven scholarships, medals in Latin and Greek, and an arts research resident fellowship became an assistant professor of classics at the University of New Brunswick. But there were many more who made significant contributions to their fields without achieving an academic appointment. Research positions in government or university labs were a common career path, as was collaboration with their husbands, especially in the sciences. The work of 1940 winner and McGill graduate Christiane Dosne on the physiology of the adrenal cortex with Canadian scientist Hans Selye led to a number of discoveries relating to shock. After moving to Buenos Aires in Argentina, she quickly learned Spanish, studied at the Institute of Physiology, won a Rockefeller research fellowship, and published numerous articles. She married Rodolfo Pasqualini, with whom she collaborated, and had a prolific career with the National Scientific and Technical Research Council of Argentina. It does not appear that she ever held an academic post, although she taught and mentored students. In her autobiography, she stressed that her five children were of equal importance to her research in making hers a long and happy life.25 There were some winners who took circuitous career routes, delaying their work for the important roles of wife and mother, but it appears that the majority returned to some sort of research or teaching work.26

In 1952, the word scholarship was changed to fellowship to conform with IFUW usage on the understanding that the term denoted advanced research. Fellowship age limits were generally quite liberal. In the 1950s travelling and other “senior” fellowship applicants had to be under thirty-five years of age, while junior fellowship applicants had to be under twenty-five.27 No doubt the age allowance for the former was in recognition of the interrupted careers that many women experienced.

CFUW created a Professional Fellowship in the 1940s for women who, after working in a particular field, wanted to resume their education and earn a master’s degree or equivalent. Many of these were in more traditional fields, such as English major Moira S. Thompson from Fredericton, New Brunswick, who went to the University of Toronto Library School.28 Tensions occasionally arose within CFUW over which scholarship was more important, with some competition between support for advanced research in the hope of gaining academic appointments versus support for professional training. In 1958, the Scholarship Committee reported a strong preference for the Junior Fellowship over the Professional Fellowship, complaining that “Jr. scholarship applicants with excellent academic standing are continually being turned down,” while Professional Fellowship applicants were “not outstanding and generally gained well-paid positions.”29 The committee did concede that the Professional Fellowship should be retained, but they reserved the right to not award it if no suitable candidate arose.30 As is reflected in a note in the 1958 minutes, this was “a highly controversial matter with no hope of unanimity.”31

Beginning in the 1950s and picking up steam by the 1960s, the expansion in women’s university attendance was opening up more academic appointments for women. The Chronicle reported in 1955 that twelve former scholarship winners were teaching in universities, including Margaret Crichton, who was teaching German at the University of Wisconsin; Enid Goldstine and Margaret Cameron, who were teaching French at the University of Manitoba and the University of Saskatchewan, respectively; Dorothea Sharp, as mentioned earlier, teaching Greek and medieval political ideas at the London School of Economics; Jeanne Le Caine, teaching mathematics at Oklahoma A&M College; Gladys Downes and Barbara Craig teaching French at Victoria College and University of Kansas respectively; Naomi Jackson, teaching fine arts at McMaster University; Doris Saunders and Joyce Hemlow, teaching English at the University of Manitoba and McGill respectively; Dixie Pelluet, teaching biology at Dalhousie; and Mary White, teaching classics at the University of Toronto.32

In the 1960s, well-qualified women from the humanities and sciences continued to apply although both applicants and winners were predominantly in the humanities.33 In 1966, for example, the winners were studying psychology, town planning, English, and history. The family status of winners was changing, too. No longer were women required to be single in order to be admitted to graduate programs, and it was not at all unusual to see married women among the recipients. In 1961, Dr. Camilla Odhnoff, who was married and the mother of three children, won the Vibert Douglas Fellowship, which had been established in 1956 to honour the first Canadian to serve as IFUW president. Still, the event of a woman declining a fellowship when she married was not unheard of, as one 1963 fellowship winner did.34

Administered by IFUW and paid for with CFUW funds, the Vibert Douglas Fellowship was awarded to applicants at the PhD level who were studying in a country other than the one in which they were educated or habitually resided. This reflected the wishes of the founders to encourage international experience for women scholars and contribute to worldwide understanding. In 2016, the CFUW/Vibert Douglas Fellowship was awarded to Laura Jan Obermuller from Guyana, who was studying at the University of St. Andrews in the UK, looking into ways that forest preservation could mitigate climate change.

In 1966, CFUW archivist Edna Ash contemplated a centennial publication in honour of these scholarship holders. She sent out a questionnaire to 105 of them, covering the years 1921 to 1963. Although a publication did not materialize, Marion Mann reported on the survey in the 1969 Chronicle.35 The overwhelming majority of these scholarship winners held three degrees each, and half of them had PhDs. Among the seven earliest winners, four had been granted honorary LLDs. They represented nearly every discipline and all Canadian universities established before 1960. Almost all had published works. The most frequently named profession was professor, and the majority of these were working in Canada.

Such numbers reflected a considerable achievement toward one of the major goals of the organization, as well as an improvement over the early years. A booming economy in the postwar years had clearly helped women make inroads into the academic professions, even if many were still at the lower echelons. Among those who were not professors, many worked in teaching, library work, and research. Not one of them held an elective office, however. The Chronicle report highlighted pioneers such as Alice Wilson and noted that many, including Doris Saunders and Dr. Marion Mitchell Spector—the latter a second vice president of AAUW, were leaders in the organization.36 It was also reported that many of the winners were married—half of the Travelling Fellowship recipients, four-fifths of the Junior Fellowship holders, and two-thirds of the Professional Fellowship winners. Of these, half of the winners of the Travelling McWilliams Fellowship, created in 1968 by a merger of the Margaret McWilliams and Travelling Fellowships,37 had children, while two-thirds of Junior and Professional Fellowship winners did. Marital bliss was no longer impossible for the female professor, if not without its challenges. CFUW proudly reported that regardless of family size, the vast majority of winners had pursued their professional careers largely without interruption.

Like CFUW, IFUW tried to keep track of its winners. In 1956, A. Vibert Douglas, former IFUW president and convenor of the committee set up to award international fellowships, conducted a survey of award winners. Ninety-eight fellowships and twenty-six grants had been given from 1928 to 1956 to applicants from at least twenty-

eight nations and proposed by twenty-four national associations. Of these, sixty-two studied in the arts, music, literature, archaeology, and social sciences, and the exact same number, sixty-two, went to scholars in mathematics, physical sciences, and biological and medical sciences. Out of the forty-five questionnaires returned, the organization found that all but one was active in education or research, and thirty-eight listed publications. Many listed their occupation as professor or lecturer.38

The CFUW scholarship program expanded in the postwar years, no doubt due to the increasing demand of more and more women attending university. The 1969 Scholarship Committee chair reported that the “war babies” had grown up and were “knocking on every possible door for financial assistance to continue their studies.”39 This made the committee a target for a multitude of inquiries throughout the year, which significantly increased its workload. As the number and value of the scholarships grew—by 1959 there were five fellowships that together were worth $9,000 a year—it was necessary to hire staff to help manage the program and to formalize its management. In 1967 the Charitable Trust was established as a registered Canadian charity to receive donations, manage funds, and issue charitable tax receipts. The Trust also administered the Library Award, which had begun in 1946 as the Reading Stimulation Grant administered by the Library and Creative Arts Committee. The Creative Arts Award began as a small grant in support of young music composers, making it possible for the winner’s composition to be performed professionally and a copy of it deposited with Canadian Music Centre in Toronto. Both of these latter awards were moved to the Trust’s management.40

In a late 1970s internal review of its fellowship program, CFUW noted that at least one provincial human rights commission had rejected the notion that women-only scholarships were discriminatory and the organization asserted that its awards were still relevant. Long overdue increases kept the amounts in line with comparable awards from other agencies such as the Canada Council, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, and the Medical Research Council of Canada—now the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.41

The administrative costs of running the program increased as well.42 For the 1982–1983 year, Margery Trenholme of the Fellowships Committee reported receiving seven hundred inquiries and needing help processing twenty-one French-language applications, as well as experts to assess the four McWilliams Fellowship applications. The committee benefitted enormously from the establishment of a national office in the 1990s, as well as the hiring of Betty Dunlop, whose efficient administration of the program has led to improvements over the years.43 Recently, most of the work has moved online, substantially reducing the amount of paperwork and staff time. In 2019, CFUW started accepting applications and administering the selection process electronically, which also proved to be more appealing to applicants.

Over the years, new awards have been added, and new names have been given to older awards. The Margaret McWilliams Pre-Doctoral Fellowship is now open to any woman who has a master’s or equivalent degree from an accredited university and is well advanced in her doctoral program. The small Alice E. Wilson grants given to women to upgrade their education, originally restricted to club members, had to be opened to all applicants to meet charitable status requirements. The Alumnae Association of the Collège Marguerite Bourgeoys donated $8,000 to the Trust to create the Georgette LeMoyne Fellowship. LeMoyne was one of the first women to receive a university degree in French Canada. In the new millennium, the Massey Award was created by late CFUW member Elizabeth Massey to be presented to a postgraduate student in art, music, or sculpture.44 In 2005, the Canadian Home Economics Association transferred its two postgraduate awards, the Ruth Binnie Award and the Home Economics Association Award, presented to master’s and PhD students in home economics and human ecology, to CFUW. Binnie had been a founding member of the Nova Scotia Home Economics Association. CFUW national office also created the Polytechnique Commemorative Award as a memorial to the victims of the Montréal Massacre of December 6, 1989, with special consideration given to those studying issues relevant to women. In 2015, the Linda Souter Humanities Award was presented to a master’s or doctoral student studying in the humanities. CFUW’s Aboriginal Women’s Award (AWA) was a reiteration of an earlier award honouring Marion Grant and was launched in March 2015, with a transfer from the Wolfville Club to CFUW Charitable Trust.

CFUW has kept its awards relevant to its wider goals. The AWA award, for example, reflects the organization’s commitment to service and advocacy, especially to its national initiative on Indigenous Peoples. For Alana Robert, the 2019 recipient who attended Osgoode Hall Law School, the award allows her to continue doing work “focused on combatting gender-based violence and enhancing opportunities for Indigenous peoples. …the AWA allows me to use my legal education to advance the individual and collective potential of Indigenous women.”45 Her studies in the test case litigation clinic focused on creating new legal precedents that will bring about social change. Co-president of the Osgoode Indigenous Students’ Association, Alana Robert participated in the Kawaskimhon National Aboriginal Law Moot and testified before the House of Commons standing committee on the status of women.

Clubs have played an important role in supporting CFUW scholarly awards, not only by contributing to the federation awards through their dues, but also in creating and managing their own scholarships and bursaries. The Ottawa Club launched its first scholarship in 1935,46 and the Queen’s University Alumnae Association in Kingston established the Marty Memorial Scholarship in 1936, named for Dr. Aletta Marty, who earned her MA in 1894 and was Canada’s first female school inspector, and her sister, Sophie, who was the head of modern languages at Stratford Collegiate.47 Over the years, the scholarships have grown and have been primarily awarded to local women in post-secondary institutions or those planning to attend, as most clubs felt that this helped foster “a potential leader.”48 Such local awards complement the federation’s postgraduate focus. Like CFUW, some clubs—such as Saskatoon, for example—have also created trust funds to provide for long-term investment that allows them to offer tax receipts for donations, and to keep the financial administration of the award separate from the club’s regular activities.49 A few club awards are administered through the Charitable Trust, including the Margaret Dale Philip Award sponsored by the Kitchener-Waterloo Club. In 1990–1991, the University Women’s Club of North York donated money for the Beverley Jackson Fellowship, which is open to women over the age of thirty-five.50 The Wolfville Club established the Dr. Marion Elder Grant Award in 1992 out of a bequest from Grant’s estate, intended for graduate work in Canada or abroad, with preference going to Acadia graduates.51

CFUW has been especially sensitive to the needs of mature women returning to school in the postwar era. Locally, these took many forms.52 The Regina Club established the Harried Housewife Scholarship for at-home mothers wanting to upgrade their education. Although some members objected to the name, it caught on. Many clubs used scholarships to honour prominent women. In 1964, for example, Regina created a scholarship in the name of Helena B. Walker, one of the club’s first presidents and the city’s first female alderman, who had died that year.53 The club created another one to commemorate Maureen Rever, a student of Luther College who won Olympic medals in track in 1956 and later earned a PhD and taught biology at the University of Saskatchewan.54

A 1991 study conducted by the Weston Club found that clubs of a median size of sixty members had donated an impressive $230,000 in scholarships and bursaries, with the amounts awarded ranging from $25 to $8,000. A typical award was granted to a female high school student with a high average who was headed for fulltime post-secondary study, with a wide variety of priorities such as mature women, the disabled, Indigenous students, women studying engineering, or Canadian studies. Many clubs took into account leadership qualities, community involvement, sportsmanship, and extracurricular activities. A small but growing trend was to support community college and part-time students and a few awards were even given to men. Some clubs had emergency funds for special cases and often worked with a university registrar in these situations. Typically, the selection of candidates was made by the high school staff, who then notified the club and arranged to have a representative at the commencement to present the award. Some of the awards for larger amounts had a selection committee to which the students were required to submit application forms; following this process, the club then invited the students to attend a dinner, club meeting, or commencement.55

At the beginning of the 1990s, the federation expressed their hope that, in the future, they could offer more and larger fellowships and they were disappointed when the recession prevented that from happening.56 Success did come later, however. As part of its 100th anniversary celebrations, the federation set a goal of the raising of an additional $100,000 for the Charitable Trust. By May 2019, the combined total of donations to the Trust and additional local awards was $214,169, making it possible to grant additional awards.57

Today, CFUW clubs together with the Charitable Trust award about $1,000,000 annually in fellowships, scholarships, and bursaries, supporting women financially and emotionally while they pursue postgraduate education. Governed as a separate entity from CFUW with its own board of directors, including the sitting CFUW president, there have been only minor changes to the composition, structure, and terms of the directors of the Trust since 1976, when it was allowed to build a reserve fund for future awards and award increases. The Trust is funded through a portion of members’ dues, through club and individual donations, and memorial gifts from clubs, as well as fundraising events such as the Charitable Trust Breakfast at the AGM, at which a fellowship winner is invited to speak.58

Today, the volume of awards presented and the greatly increased number of winners who have gone on to successful careers makes it difficult to pay the same close attention to each woman as was possible from the 1920s to the 1950s. The world has changed immeasurably since then. While the early pioneers who inspired the formation of the CFUW were a special, rare, and very small minority, that is no longer the case today. Indeed women outnumber men at most campuses, constituting 68 per cent of undergraduates in 2009, with nearly as many in the master’s category and only slightly less than 50 per cent of PhD students.59 While this does represent progress, women are still congregated in certain areas of study and the small minority who become professors remain at the lower levels of the academic pay scale, often in non-tenured or sessional appointments. CFUW’s fellowships promote women’s equality and improved economic wellbeing. As long as women continue to earn significantly less than men do, they are disproportionately affected by rising educational costs and rising student debt.

CFUW’s fellowships go a long way toward ensuring that the Dixie Pelluets and Alice Wilsons of today will be able to achieve the true equality they, and indeed all women, strove for.

Footnotes for this chapter can be found online at: http://www.secondstorypress.ca/resources