CHAPTER 7

Know Your Strengths and Their Shadows

We talk about quality in products and services. What about quality in our relationships, quality in our communications, and quality in our promises to each other?

—MAX DE PREE

A 2011 study looked at whether extroverts or introverts were more effective as leaders.1 To align our definitions: extroverts gain energy by sharing ideas in a group and lose energy working alone. Conversely, introverts value the opportunity to evaluate a situation and consider alternatives thoroughly; they lose energy when participating in meetings where rapid-fire choices must be made. The study found that leaders of both types were equally effective—as long as they surrounded themselves with people of the opposite style. The least effective leaders were found to be those who surrounded themselves with people like themselves. As a high potential, be aware of your strengths and your people’s strengths. Understand that each of your strengths has a shadow side, and consciously construct a team that has complementary strengths.

For example, the new, strongly extroverted group vice president of a large firm called a two-day off-site with his mostly introverted executive team. The group spent the first day imagining possibilities and considering new ideas; the facilitator purposefully kept the discussions broad. After dinner, the group president pulled him aside and said, “The meeting isn’t going well—we haven’t made any decisions yet. This off-site must produce clear goals.” The facilitator responded, “Trust the process. You’ll see decisions tomorrow.” The group president reluctantly gave him until noon the next day for key decisions to be made.

That evening, the IT executives held impromptu conversations to exchange views on the concepts that had been presented during the day. They pondered the alternatives and discussed them again at breakfast the next morning. When they reconvened, the discussions were lively and focused. Decision after decision was made with near-unanimous agreement. The group president was amazed. He always considered his ability to make rapid decisions to be a strength, but he learned a valuable lesson that day about giving people—especially introverts—time to consider alternatives. When he acknowledged this “aha” moment to the executives at the end of the off-site, their relationship was off to a great start, and everyone was aligned behind the group’s clear goals.

Each Strength Has a Companion Shadow

Few things reveal leadership strengths and shadows more vividly than high-pressure situations—an impending deadline, extra scrutiny from the boss, a conflict among top executives, a high-stakes decision. During the stress of these situations, consider that

- Any strength taken to excess can become a shadow that derails the relationships required to achieve success.

- Embracing and integrating the strengths of each person will maximize the team’s power and minimize its collective shadows.

- Over time, you will develop new strengths and workarounds for your shadows.

Knowing and acknowledging your leadership strengths and their companion shadows establishes a robust foundation for relationships. For example, one top CIO in the U.S. government describes his leadership strengths and shadows to his people as follows:

- My Style: I’m blunt and transparent. I like debates and direct feedback. I ask a lot of questions—don’t take them personally. I delegate and I encourage calculated risk-taking. I like structured processes and procedures. I insist on a family-friendly team—your family comes first.

- What I Expect from You: Fierce loyalty. Represent the organization well at all times. Do a quality job on time. Don’t give up. Be creative—a person who says it can’t be done is often interrupting a person who is doing it. Mistakes are okay as long as they are made with the best intentions and we learn from them. Be accountable. Follow official policies. Focus on the customer. Be nice.

- Joint Responsibility: Communicate well and often. Teamwork means we watch each other’s backs. If you need help, ask for it. We will succeed if we work as a team, or fail working as individuals. Always close the loop.

- When to Contact Me: With ideas, recommendations, feedback, or complaints. When things are going very well and not so well. Don’t let me get blindsided. If you need help, I’m accessible 24/7.

- My Vision: Success is when: (1) every employee is excited about what he does; (2) every government employee wants to work for us; and (3) every federal agency wants to use us as their trusted IT partner.

He has this conversation with each new hire to define their relationship, communicate expectations, and establish how best to interact. This welcome-aboard message begins the leadership conversations in his organization.

Getting Started on the Right Foot

The early conversations between executives and their direct reports establish the blend of management and leadership mindsets that persists throughout the relationship. For example, consider the following conversation between an executive leader and high-potential manager who has just been hired into the organization:

“I look forward to us getting to know each other, and see you as a valuable addition to the team. We have a lot to accomplish and can only meet our stretch goals by working closely together. For the moment, let’s not talk about the goals. Instead, let me tell you a bit about our culture and about what makes me tick as the boss, and ask you to share the same about yourself. To start, tell me, why did you choose to join our team?”

This conversation—and therefore, the relationship—opened in a leadership mindset, while the management-mindset conversation about goals, roles, and resources was put on hold temporarily. Beginning the conversation by connecting with one another increases the likelihood that a relationship will be created that can endure future challenges. A typical response by the new manager might sound something like this:

“Thanks for asking. I sensed this was a great place to work—that people matter here. In my last position, everyone had a different idea about how the job should be done, and competition was intense. The boss blamed us when things didn’t go well and took credit when they did. We rarely knew what he was thinking, and his conversations with us were merely appeals for us to work harder and do more. I came here because this organization uses a more people-oriented approach.”

By creating a safe place for the new manager to reveal what was important to him, the boss gained critical insights on how to motivate him. The conversation also validated the boss’s policy to focus on relationships and attitudes in his hiring decisions. The boss continued the conversation:

“I’ve arranged for you to meet key members of the team over the next few days. Get to know them as trusted and respected colleagues as you dive into the new position. Then we’ll have the conversation about goals and mutual expectations. Our team enjoys work, and we build relationships to ensure that everyone succeeds. That’s why our customers love us, and that’s how we outperform our competitors and the other divisions.”

The messages exchanged during this conversation clearly establish that the boss, the new manager, and others—the people, not just the results they produce—are critical to the team’s performance. The new manager both relaxed and became more excited, and the boss felt good about the hiring decision. As a high potential, you probably have already participated on both sides of similar conversations. Conversations to build relationships are largely about making conscious connections that lead to alignment in decisions and actions.

Developing Unconscious Competence in Relationships

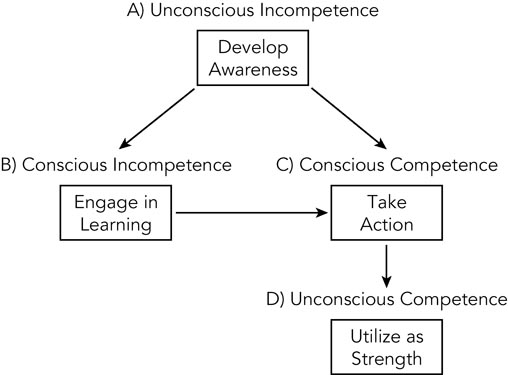

The conscious competency model illustrated in Figure 7.1 describes the process for developing a new strength.2 To understand the model, begin with (A) unconscious incompetence, which is the state of not knowing that you need to know something. A skill that is not a current strength but that you recognize as important and that you acknowledge as necessary to learn is called a (B) conscious incompetency. When you become aware of the new skill and work to become proficient, you have a (C) conscious competency. When the skill becomes second nature—a (D) unconscious competency—it is a strength that you rely on naturally.

As a practical example of the model, consider breathing: for most of us, this is a fully developed unconscious competency. Yet the ability to consciously control breathing is advantageous in stressful situations. For example, scuba divers are acutely aware of how their breathing varies when they are calm, exerting effort, or in panic mode, because that skill can save their lives. They are unconsciously competent in breathing under all, not just normal, circumstances. New divers must learn to control their breathing under all circumstances because breathing underwater is different than doing so on land. It takes practice to breathe smoothly and manage an air supply. Novice divers gulp a tank of air in fifteen minutes, whereas the same tank may last an experienced diver an hour. The conscious competency model is relevant to leadership because building relationships is as essential to leaders as breathing properly is to scuba divers.

Observe what others do who are proficient relationship builders. Become aware of what you do not know and learn what you need to know. For instance, you may have noticed that some successful leaders are outgoing and some are curious. Now isolate the traits of being outgoing and curious—become conscious of their importance. The next step is to determine if you are competent in these two traits. If not, identify what keeps you from being outgoing or curious (or both) so that you can learn what you need in order to become competent at them. Becoming consciously competent, you will meet people and use curiosity as a basis for building interesting relationships. As you develop these traits, you will find yourself being outgoing and curious in your relationships without consciously trying. Then you have achieved an unconscious competency that you will use naturally and continually.

Recognizing the Shadows

The process of becoming unconsciously competent in a new skill is as important as the competency itself. Most of us have worked with someone whose strength was an ability to quickly assess a situation, decide what to do, and direct others to take action. Look at that style in terms of the conscious competency model. For those executives, springing into action is an unconscious skill they habitually employ when facing tight deadlines or perceived threats. In routine situations, that approach can be a shadow in terms of inhibiting their teams’ professional growth and long-term performance.

A team’s performance generally can be enhanced by identifying the strengths required to perform a task (becoming aware), considering whether you possess them (a conscious competency) or need them from someone else (a conscious incompetency). When you blend the strengths of each team member to complete the task, the team usually will be more creative, find a more effective strategy, and align better for execution. Just as important, the team feels vested in the strategy and forms more productive relationships—the shadows have been erased by the collective strengths of the team.

Furthermore, think about the mindset of an executive who immediately springs into action. He is relying solely on his skills to devise the strategy, set the schedule, and push people into action. Thinking much like an independent contributor, he feels confident in setting the agenda by himself and using people like marionettes. That executive is unconsciously incompetent (a shadow area) relative to

- Developing others by allowing them to set the agenda

- Freeing himself to work on more complex parts of the task

- Recognizing that teamwork is essential for superior long-term results

Engaging the strengths of others—particularly in your shadow areas—will instill the team with confidence in your leadership skills and your ability to build relationships.

There is another lesson in observing executives who spring into action—they must learn to engage in leadership conversations. These executives tap their personal strengths but ignore the strengths of others. What might happen instead if they posed leadership questions to the group, such as “Take a few minutes to identify your strengths relative to this task and describe them to us” or “What obstacles do you think we’ll encounter, and how should we conquer them?” Questions like these take less time than you might think, and save time during subsequent steps because they engage all of the group’s strengths and build relationships that are useful today and strong in the future. In the long run, conversations that connect and align make a larger contribution to a group’s performance than any “perfect” plan a leader might dictate all by himself.

As a leader, use both mindsets to define success criteria and determine which (and whose) strengths to call on. Determine what the team has the ability to do before deciding what it will do: “What skills or competencies is the team missing?” Independent contributors usually define their own success criteria—after all, they are experts in a narrow range of tasks. Managers focus on completing the task as quickly as possible in order to move to the next one. Leaders concentrate on delivering value to stakeholders and building relationships in the process, even though that approach may initially take more time. In addition, bring all three conversational perspectives to the meeting-room table: hear everyone’s ideas, understand what they are saying, and explore new possibilities as appropriate to the task at hand.

Focus on Strengths

Some executives attempt to convert weaknesses into strengths rather than leveraging existing strengths. The feedback they provide and formal performance reviews they hold often examine weaknesses in excruciating detail. There are few surprises because the reviewer and recipient both recognize them. The review process often ends with a plan that attempts to transform weaknesses into strengths, the underlying assumption being that everyone should be capable in every area. That is an unrealistic expectation that devalues unique skills. There are some things that a person may never be good at doing. A more effective approach in today’s collaborative, crowdsourced world is to match people in teams that collectively have all of the strengths needed to produce an extraordinary result.

Building on your strengths is a natural and essential part of climbing the leadership ladder. Get feedback, be coached and mentored, and obtain training in areas that are vital for your success. Observe your boss’s strengths and shadows—which could you use now, and which might you use when her job becomes yours? Successful leaders expand their effectiveness by leveraging strengths and working around weaknesses. There may come a time when your strengths are insufficient for your position. If you develop new strengths and relationships, you can thrive. If you do not, your status as a high potential will be at risk.

Notes

1. Grant, A. M., Gino, F., and Hofmann, D. A. “Reversing the Extraverted Leadership Advantage: The Role of Employee Proactivity.” Academy of Management Journal, 2011, 54(3), 528–550.

2. The exact origin of this model is unknown. Partial attributions have been found: Joan Flemming (1953); R. A. Hogan (1964); and an interview with Lewis W. Robinson, Personnel Journal, July 1974, 53(7), citing the four categories. Gordon Training International originated its version of this model in the early 1970s.