CHAPTER 5

Hunter Bunter’s Folly

VIII Corps’ pre-ordained failure at Serre and Beaumont Hamel

‘You see for young lads like me, those that were left, it was like a bad dream. We couldn’t take in what was happening around us. The shock of it hit us later.’1

— Private Noel Peters, 16th Middlesex

HAWTHORN MINE BLEW like a giant earthen carbuncle, heaving great slabs of clay and chalkstone skyward, along with one-score German soldiers. Debris flopped to the ground within about 20 seconds, leaving clouds of fine grey dust and smoke billowing over Hawthorn Ridge. All that remained of the redoubt that once stood there was a crater that measured 130 feet wide and 58 feet deep, including an 18-foot-high lip of chalkstone spoil that tapered off into the surrounding land. ‘The field was white, as if it had snowed,’ wrote Leutnant-der-Reserve Matthaus Gerster, of Reserve Infantry Regiment 119 (RIR119), adding the gigantic divot ‘gaped like an open wound in the side of the hill.’2 The blast of 40,600 pounds of ammonal collapsed nearby German dugouts, crushing occupants and entombing others. Some clawed their way out; others suffocated. Above ground several German soldiers were stunned by a cocktail of concussion and fear. The eruption, wrote Gerster, heralded the start of the anticipated British attack.

Lieutenant Geoffrey Malins, a British army cinematographer and shameless self-promoter, immortalised the moment with a hand-cranked movie camera. Moments before 7.20 a.m., he worried about how much film he had left. Then the ground convulsed. ‘It rocked and swayed. I gripped hold of my tripod to steady myself. Then, for all the world like a gigantic sponge, the earth rose in the air to the height of hundreds of feet. Higher and higher it rose, and with a horrible, grinding roar the earth fell back upon itself.’3 British soldiers nearby watched in awe. Many felt the shock waves ripple through their trenches.4 Several German soldiers felt the judder in their dugouts more than a mile away and wondered if it was an earthquake.5 Some in the Newfoundland Regiment mistakenly thought the village of Beaumont Hamel had been razed.6

Stand at the edge of the Hawthorn Ridge crater today and you can see for miles around. Its tactical value back in 1916 is obvious. German machine-gunners here could sweep no-man’s-land and the British assembly trenches from the Beaumont Hamel–Auchonvillers road valley around to the northern edge of today’s Newfoundland Memorial Park.

This danger was recognised by Lieutenant-General Sir Aylmer Hunter-Weston and his VIII Corps headquarters. Their concerns were centred on whether German infantry would occupy the crater first, something they had form in. But, in effect, the timing of the Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt blast at 7.20 a.m. served as a giant clapperboard that signalled the pending attack 10 minutes before it began. ‘Hunter Bunter’s folly’7 — as the blast timing became known — would have devastating consequences for VIII Corps’ infantry, which explained why pretty much everyone involved in the decision-making later scrambled for cover.

Fifty-two-year-old Hunter-Weston had served on the Indian North-West Frontier and in Egypt and South Africa before the First World War. He fought in France in 1914, and then at Gallipoli in 1915. He liked horses and hunting, wore a bushy moustache and occasionally used a walking stick. He liked posing for formal photographs, but often made candid snaps look awkward. He saw himself as a ‘plain, blunt soldier,’8 and never shied from imparting pearls of wisdom to subordinates: ‘I was given the power to strike the right note & to enthouse [sic] the men.’9 Some thought Hunter-Weston intelligent and rich in human sympathy.10 More said he was over-optimistic, often patronising or brutal in tone, unable to delegate and — the most extreme view — a charlatan.11 His penchant for inspecting latrines was no more coincidental than the ‘magnificent, gleaming’ boots and buttons at his headquarters.12 The moniker ‘Hunter Bunter’ had much to do with his pushy, self-important character. Hunter-Weston’s personality was authoritarian; he was obsessed with order, control and hygiene.13

Hunter-Weston carried a well-earned reputation for bloody daylight attacks that lacked imagination and artillery support. That dated back to Gallipoli, when the Scot was said to have been willing to ‘contend in open debate that, provided the objective was gained, casualties were of no importance.’14 This ‘logician of war’ saw few shades of grey when it came to justifying casualties in successful attacks, but, as we shall see, saw many more when it came to accounting for industrial-scale military failure and its cost.

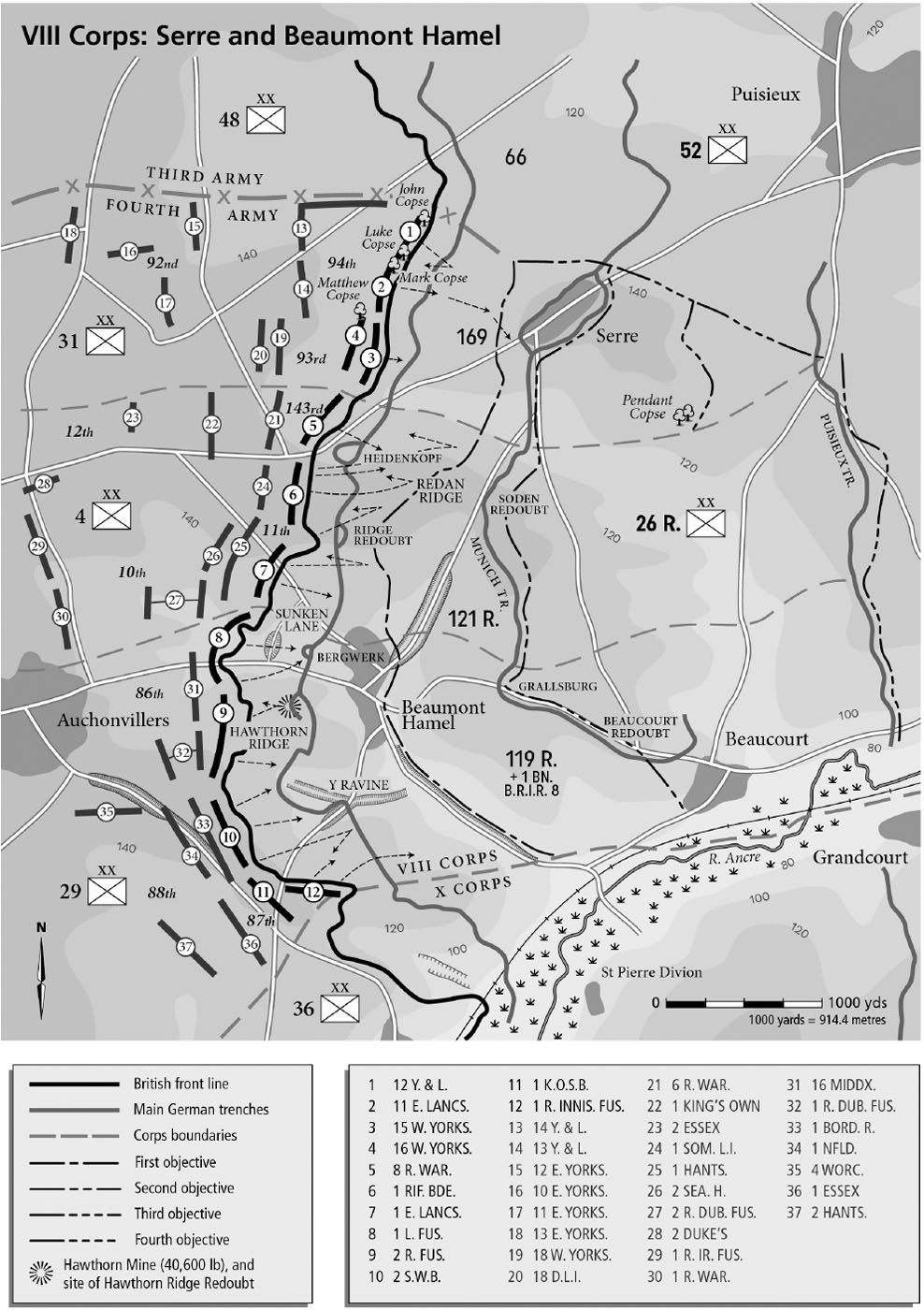

Eighth Corps opposed a trinity of formidable German defensive networks crisscrossing the high ground north of the River Ancre. From above, the German front line looked a bit like an oversized ‘L’. The down-stroke of the L blocked the uphill approaches to Serre village at its top end, and thereafter meandered southwards across a series of low-lying ridges and road valleys before arriving at Beaumont Hamel, which sat in the angle formed by the horizontal bar, then headed east to the river valley fens. No-man’s-land was 200–600 yards across, the distance generally narrower north of Beaumont Hamel than south. As we shall see, each of the attacking divisions — north to south, 31st, 4th and 29th — used a variety of tactics to help them cross the open ground between the opposing lines. Forty-eighth (South Midland) Division, less two battalions attached to the 4th, was in corps reserve.

The strength of the German defences lay in their co-ordinated redoubts and fortified villages. In the front-line system, Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt (Weissdornfeste), Ridge Redoubt and the Bergwerk covered the northern approaches to Beaumont Hamel, while Y-Ravine (Leiling Schlucht) blocked access from the south. Heidenkopf — known to the British as the Quadrilateral, and more an elbow of trenches that jutted out into no-man’s-land as a defensive feature than a redoubt — was nestled in a natural amphitheatre just south of Serre. Further back 1000–2000 yards, the intermediate position, known to the British as Munich Trench, was on higher ground again. It included Soden (Feste Soden), Grallsburg and Beaucourt (Feste-Alt-Württemberg) Redoubts, along with the fortified villages of Serre and Beaucourt. Back another 1000–2000 yards, but mostly the latter, was the second position, or Puisieux Trench, which included more redoubts and Grandcourt village on the southern bank of the Ancre. These layered defences were designed to stop any enemy attacks with a significant volume of co-ordinated machine-gun and rifle fire.

Most of this land was held by 26th Reserve Division. Its Württembergrecruited RIR119 and Reserve Infantry Regiment 121 (RIR121) occupied the trenches from the Ancre to just south of Serre. Thereafter, the trenches belonged to soldiers of 52nd Infantry Division, with the Baden-drawn Infantry Regiment 169 (IR169) defending Serre. These three German infantry regiments, all in XIV Reserve Corps, totalled about 9000 men. These faced an estimated 25,000 infantry, pioneer and engineer officers and men of Hunter-Weston’s corps who actually participated in the attack, from the total 96,794 soldiers of all ranks and units in VIII Corps.15

As mentioned earlier, German commanders regarded the subtle westfacing salient between Hamel, Beaumont Hamel and Serre as must-hold ground.16 Defences here were based on two spurs that curved behind and overlooked the front-line positions as they faded into the northern banks of the River Ancre. Fourteenth Reserve Corps and Second Army treated the Serre–Grandcourt (Serre Heights) and Redan Ridge–Beaucourt Spurs as essential because of the southeasterly views they afforded over Thiepval Plateau and Pozières,17 and also east over a string of villages towards Bapaume. Loss of this ground would render Beaumont Hamel, Beaucourt, Grandcourt, Miraumont and Thiepval untenable.18 Moreover, the 26th’s artillery lines just north of the Ancre would be lost, denuding Thiepval and Pozières of northern flank support. If this happened, the 26th’s positions around Pozières, Ovillers and La Boisselle would subsequently be jeopardised and potentially rolled up by the British.19 None of this had escaped the 26th’s commander, Generalleutnant Franz Freiherr von Soden, or his superiors at XIV Reserve Corps and Second Army, who knew the loss of the elevations behind Beaumont Hamel and Serre, and in particular Serre Heights, had significant tactical ramifications for the tenability of his divisional sector and thus spared no effort in making it impregnable.20

Hunter-Weston planned to break this German fortress with a frontal infantry assault supported by artillery. His three divisions would attack to a depth of 3000–3500 yards and link up side by side on Serre–Grandcourt Spur, its final objective, by midday. In so doing it would provide flank support for Fourth Army’s main thrust towards Pozières. This spur also had a wider value in that it provided a foundation from which the under-construction German third defensive line and a handful of villages could later be assaulted.21 The initial stages of Hunter-Weston’s advance were the toughest to complete as these involved a mostly uphill operation against the multiple fortified villages and redoubts. Furthest north, 31st Division would capture Serre before moving onto the high ground beyond, while immediately south 4th Division would attack astride Redan Ridge and seize Ridge Redoubt, Heidenkopf and Soden Redoubt before coming up alongside the 31st. Twenty-ninth Division was to take Bergwerk, Beaumont Hamel, Y-Ravine, Grallsburg, Beaucourt Redoubt and Beaucourt village before arriving at the southern end of the spur. Attainment of these ambitious objectives was reliant on VIII Corps’ artillery nullifying resistance during both the seven-day bombardment and the battle-day barrage.22

Eighth Corps’ gunners had three tasks. They had to kill or neutralise Württemberg and Baden infantry, destroy defensive obstacles and mechanisms such as barbed wire and machine-gun posts, and also suppress hostile artillery grouped further back. Prior to Zero hour, this was the purpose of the prolonged bombardment, and during the attack it was the job of the supporting barrage. In the period 24–30 June, VIII Corps’ artillery fired almost 363,000 heavy and field artillery shells at the German positions.23 On 1 July they would fire about 61,500 shells.24 Impressive as these figures appear, they do not take into account the number of duds, the dilution of shellfire over a wide area, the weighting to shrapnel over explosive shells, or the difficulties in locating and then destroying distant targets given the technology of 1916. There were other problems, too. In Hunter-Weston’s battle sector, Fourth Army had allocated the equivalent of about one field gun to every 20 yards of attack frontage, and about one heavy barrel for every 44 yards.25 This concentration was, even a year later, considered ridiculously low.26 At the time Hunter-Weston waxed lyrical about the cut wire, which in many places remained intact, and German trenches that were ‘blown to pieces.’27 He reckoned his corps had only to ‘walk into Serre.’28 As events would show, Hunter-Weston’s optimism was entirely misplaced because VIII Corps’ artillery had failed in all three of its essential tasks.

Brigadier-General John Charteris, General Sir Douglas Haig’s chief of intelligence, visited Hunter-Weston late on 28 June. As mentioned previously, he had Haig’s authority to stop VIII Corps’ attack if he thought it wise.29 He found Hunter-Weston and his divisional chiefs convinced they would achieve a great success and approved the attack. ‘The Corps Commander said he felt “like Napoleon before the battle of Austerlitz!”’30 It was a careless line that revealed much about Hunter-Weston’s delusions.

There were more troubling problems in that VIII Corps’ artillery programme for 1 July was unfit for purpose. The plan was for Hunter-Weston’s infantry to be presaged by a timetabled barrage. It was to start on the German front line and step back at six set intervals until the final objective was taken. But Hunter-Weston fiddled with the timetable to accommodate the mine-blast timing: infantry could not seize the crater if heavy artillery was shelling the area.31 Astoundingly, he ordered his corps’ heavy artillery to lift its shellfire off the entire German front line opposite his corps at 7.20 a.m. to targets further back, rather than just that opposite 29th Division.32 Field artillery would step its ‘thin’ fire further back at 7.30 a.m., but in the 29th’s sector it would be halved from 7.27 a.m.33 Gunnery officers tweaked their fire plans, but infantry planners were oblivious.34 It was a classic case of left hand not knowing what the right was doing. The result would be thousands of British infantrymen stranded in no-man’s-land for up to 10 minutes before their attack began and exposed to the enemy’s defensive artillery and machinegun fire. As far as blunders went, this one was pretty big and, as we shall see, guaranteed disaster for Hunter-Weston’s infantry.

Eighth Corps had at first wanted the mine blown at 6 p.m. on 30 June,35 and then changed the timing to 3.30 a.m. on 1 July, so that the crater could be seized before the main attack.36 General Headquarters (GHQ) wanted it shifted to 7.30 a.m.37 Hunter-Weston said the blast was advanced to 7.20 a.m. at the request of 29th Division to avoid having infantrymen hit by falling debris as they crossed no-man’s-land.38 The 29th’s commander, Major-General Beauvoir de Lisle, denied this.39 He blamed the mining officers. The mining officers blamed VIII Corps and one another. So it continued. Most pointed an accusatory finger at Hunter-Weston. It turned out nobody in VIII Corps had wanted the 7.20 a.m. time slot, but somehow that was what they got.40 It is damning to find Hunter-Weston begrudgingly admitting responsibility later.41

Hunter-Weston’s mine-timing decision was apparently queried several times by concerned senior artillery officers.42 But the general was ‘not to be moved from his scheme,’ wrote Major John Gibbon, Royal Artillery.43 ‘We knew [the attack] was foredoomed to failure.’44

‘EVERYONE KNEW . . . IT was important not to miss the moment that the [British shell] fire moved back [to more distant targets] and the infantry assault began,’ wrote Leutnant-der-Reserve Gerster, RIR119.45 That signalled the start of the so-called race for the parapet. The winner was whoever reached the German front line first; the greater the margin the better. As it turned out, both the shelling debacle and the mine explosion gave German defenders an unrecoverable head start as Hunter-Weston’s infantry were deploying hundreds of yards away in no-man’s-land. At the same time, as a German officer just south of Serre recalled, the British barrage ‘lifted onto our rear positions and we felt the earth shake violently — this was caused by a mine going off near Beaumont. In no time flat the slope opposite resembled an ant heap.’46 German infantrymen raced up from dugouts and into the shellfire-torn trenches, propping rifles and machine guns on broken parapets and shell-crater rims; they were ready and waiting, 5–10 minutes before the British attack even began.47 Hunter-Weston’s meddling had lost his infantry the parapet foot race by quite some distance.

One British soldier chanced a peek towards the enemy parapet as the barrage lifted. ‘Out on the top [of the trench] came scrambling a German machine-gun team. They fixed their gun in front of their parapet and opened out a slow and deadly fire on our front.’48 At that moment many soldiers realised they were doomed. Heavy casualties were inevitable. Here and there some machine guns were chattering away before the bombardment even lifted.

Disaster, if not massacre, followed. Within moments a lopsided battle was raging.49 German machine-gunners fired staccato bursts. Riflemen drew careful bead. Shellfire tore down whole groups of British soldiers.50 ‘Despite the protection of the wooden rifle stock [around the gun barrel], the skin on their left hands burned,’51 said Gerster, who fought on Hawthorn Ridge. There were ‘shouted commands, cries for help, messages, death screams, shouts of joy, wheezing, whining, pleading, gun shots, machine gun fire crackling, and shell explosions.’52 He continued: ‘Everywhere the [British] skirmishing line crumples. Khaki-brown spots cover the broken earth. Arms are thrown in the air, indicating death. We can see people rushing back wounded, or sheltering in shell craters. The severely wounded are rolling on the ground.’53 VIII Corps’ attack was irretrievably faltering before it had even really begun.

Red flares rising skyward from the German front line and urgent calls from artillery observers quickly brought down a hurricane of shrapnel and explosive shellfire. In some places it began around 7.20 a.m. In others, such as in 31st Division’s area, it started at about 7 a.m.54 Bigger German guns systematically pummelled the British trenches. Lightercalibre weapons threw down a curtain of shellfire on no-man’s-land to impede successive waves of attacking infantry. Nominally about 61 guns, or 40% of 26th Reserve Division’s 154 artillery pieces, were deployed between the River Ancre and Heidenkopf.55 These were complemented by an estimated 35 guns of 52nd Infantry Division behind and to the north of Serre.56 While many guns had been damaged or destroyed by the British bombardment, plenty had survived, were stocked with ammunition and now began shooting at pre-allocated target zones.57 ‘On the morning of 1 July virtually all batteries [surviving the bombardment] are fully ready to fire,’ said Major Max Klaus, Reserve Field Artillery Regiment 26 (RFAR26).58 This was the benefit of XIV Reserve Corps having insisted that its gunners preserve firepower through fire discipline.

‘This barrage which fell at Zero was one of the most consistently severe I have seen,’ said Brigadier-General Hubert Rees, commanding 94th Brigade, of the scene in no-man’s-land and within the British lines.59 ‘It gave me the impression of a thick belt of poplar trees from the cones of the explosions. As soon as I saw it I ordered every man within reach to halt and lie down but only managed to stop about 2 companies because all troops had to move at once in order to capture their objectives on time. It was impossible for any but a few men to get through it.’

The botched mine blast and initial barrage lift comprised the first element of a three-act tragedy. The second act, which had yet to begin, was all about 4th, 29th and 31st Divisions’ generally disastrous attacks in the two-and-a-half hours to about 10 a.m. The third was played out on Hawthorn Ridge and at Heidenkopf, where destinedto-fail British incursions took on the qualities of epics that belied their actual importance. In truth, few soldiers would have recognised these distinctions; for them it was mostly a day-long horror story bare of any redeeming qualities.

THE SECOND ACT began with 29th Division’s attacks across a 200–600 yards-wide no-man’s-land around Beaumont Hamel failing by about 8 a.m. Here — in keeping with the popular imagery of soldiers advancing in unwavering lines — all of the 29th’s attacking battalions were ordered to press forward in columns of sections, although some minor tactical variations were used in places.60 Overall, however, the tactics used by the 29th to get its infantry across no-man’s-land and into RIR119’s trenches did precisely nothing to lessen the slaughter that was about to follow.

Each of the 29th’s three brigades had a section from either 1/1st West Riding, 1/3rd Kent or 1/2nd Field Companies, Royal Engineers (RE) attached for consolidating gains.61 Two companies of 1/2nd Monmouths* were split up across the 29th’s leading attack battalions for carrying and consolidation work. Two Russian Saps in the 29th’s area — First Avenue and Mary, both well out into no-man’s-land — were used as Stokesmortar emplacements. These tunnels were quickly clogged with wounded and battle stragglers, and repeated efforts to link and extend them to the German line by the remaining half of 1/2nd Monmouths failed under a torrent of bullets.62

Twenty-ninth Division’s 86th and 87th Brigades, respectively commanded by Brigadier-Generals Weir Williams and Cuthbert Lucas, attacked side by side. The 86th was astride the shallow Beaumont Hamel–Auchonvillers road valley. To the north, 1st Lancashire Fusiliers† — two of its companies racing forward in extended order at 7.30 a.m. from a sunken lane in no-man’s-land and the rest overland in columns of sections from the British front line behind them — was dropped by machine-gun and rifle fire.63 Sap 7, an unopened Russian Sap linking the sunken lane and the British front line, was soon filled with wounded trying to get back. It was a similar story for the rump of 2nd Royal Fusiliers* immediately south, with less than 120 from one of its companies having raced forward minutes before Zero to find German infantry already at the smouldering Hawthorn Ridge crater.64 Support battalions 16th Middlesex† and 1st Royal Dublin Fusiliers‡ were similarly swept down as they crossed the front line just before 8 a.m. and attempted to pass through their own wire and move forward.65 Further south, again, the 87th’s 2nd South Wales Borderers§ began deploying at 7.20 a.m. in the area now known as Newfoundland Memorial Park and was taking casualties around its own front line and as men bunched to pass through gaps in their own wire.66 None made it across the bullet-swept no-man’s-land and into the German trenches.67 The same fate befell 1st Borders¶ as it followed immediately behind.68 Opposite Mary Redan salient, closer to the River Ancre, the decimation of 1st Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers** began as it left the British front line at 7.30 a.m. under heavy machine-gun fire.69 A few apparently won their way into the hostile trench, but these were driven out, captured or killed.70 First King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB)†† followed and made no headway.71 Virtually none of 29th’s initial attack battalions reached the German lines; their dead, dying and wounded lay thick around the British trenches and in no-man’s-land.72

One officer of 1st KOSB complained bitterly about the lack of secrecy in preparing his battalion’s attack. This applied equally across the combined fronts of 86th and 87th Brigades. ‘The advertisement of the attack on our front was absurd. Paths were cut and marked through our wire days before. Bridges over our trenches for the 2nd and 3rd waves to cross by were put up days in advance. Small wonder the M.G. [machine-gun] fire was directed with such fatal precision.’73 The result, as 1st Borders’ war diarist noted, was that multiple battalions advanced at a slow walk ‘until only little groups of half a dozen men were left here and there, and these . . . took cover in shell holes or where ever they could. The advance was brought entirely to a standstill.’74 These grim themes were repeated in the battle reports of multiple battalions,75 and it was evident, too, in the diaries and memoirs of those lucky enough to survive the machine-gun maelstrom.

Sergeant George Osborn, 2nd South Wales Borderers, expected to die:76 ‘My word, we found ourselves in a hot shop.’77 He ducked into a shell hole and knew it was ‘certain death to move.’78 A bullet carried away Private Derek McCullock’s right eye, and soon afterwards shrapnel caught the 16th Middlesex soldier in the torso and legs. ‘My collar bone, shoulder blade and two ribs were broken and I had a bullet in my left lung. I managed to crawl back to our lines.’79 Private Peter Smith, 1st Borders, miraculously reached the intact German wire where he, too, ducked into a shell crater. ‘The Jerries started throwing bombs, we had to retire.’80 He and four others later scampered back over a field of corpses: ‘It was pure bloody murder.’81 Sergeant Alexander Fraser, 1st Borders, said seven men of his 34-strong platoon were wounded as they clambered out of a support trench well behind the British front line: ‘All I could do was lay these [seven] chaps on the fire step [of the trench]. We weren’t allowed to do anything for them and make sure the next chaps went up. Seven hit out of one Platoon going out and I still had to go up [the trench ladder].’82

It was a story repeated all around the 29th’s lines and is reflected in the division’s casualty roll for 1 July. The 29th booked about 5240 casualties, among them 1628 dead, 3107 wounded, 220 missing, 32 prisoners and 253 unspecified. Across no-man’s-land, RIR119 suffered 292 casualties on 1 July, these comprising 101 dead and 191 wounded.83 In brief, for every one German casualty opposite the 29th, there were 17.9 British: a ratio that includes a premium for Hunter Bunter’s meddling.

Shortly after 7.30 a.m., Major Edward Packe, 15th Squadron, Royal Flying Corps, was 2000 feet above the Beaumont Hamel battlefield in an open-cockpit BE2c. The sight of numerous dead in no-man’s-land horrified him: ‘Only in two places did I see any of our troops reach the German trenches, and only a handful at each.’84 Soon enough, Packe himself copped a bullet in the buttocks from ground fire and returned to base.

Somewhere out among the dead was 24-year-old Private John McDonnell, 1st Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. The married man and father from County Tyrone is today buried at Ancre British Cemetery. His wife, Mary, later chose the epitaph upon his headstone:

At our fireside,

Sad and lonely,

The children I do tell,

How their noble father fell.

FOURTH DIVISION’S INITIAL attack was eastbound on a 1500-yard front between Redan Ridge and Heidenkopf. Here, immediately north of 29th Division, there was plenty of failure, but also some initial gains. ‘We sprang like cats on the [trench parapet] top, and then we had to walk,’ said Private Thomas Kirby, 1st East Lancashires.85 The assault was led by three battalions — south to north, 1st East Lancashires, 1st Rifle Brigade (both of 11th Brigade) and the 1/8th Royal Warwicks, this last attached from 48th (South Midland) Division’s 143rd Brigade — going over abreast and moving forward in linear successive waves.86 Three more — 1st Hampshires, 1st Somerset Light Infantry and 1/6th Royal Warwicks, also of the 143rd — followed in section columns to mitigate the effect of an expected defensive barrage.87

Sections from 7th, 1/1st Durham and 1/1st Renfrew Field Companies, RE, were to help with consolidation.88 Four Russian Saps in 4th Division’s patch had Lewis-gun teams at their respective heads in no-man’s-land. The men at the heads of these saps — north to south, Delaunay and Bess Street in 1/8th Royal Warwicks’ sector, and Cat Street and Beet Street in 1st Rifle Brigade’s zone — quickly fell prey to so-called ‘friendly’ shellfire or enemy infantry.

German machine guns in the front and support trenches spat lead directly at the attackers. ‘When the Germans saw us coming they did not half open out with [artillery] heavies and machine guns,’ said Kirby.89 Machine guns to the north around the ruins of Serre, where 31st Division’s attack was a failure in progress, and south at Ridge Redoubt, caught 4th Division in brutal enfilade.90

As it turned out, 4th Division’s two northern-most lead battalions made limited gains around Heidenkopf, whereas the third met with outright failure on the camber of the east–west running Redan Ridge. Eleventh Brigade’s 1st East Lancashires* moved into no-man’s-land on the ridge shortly before Zero and met with heavy machine-gun fire.91 About 40 men fought their way into the hostile line and were killed or captured.92 Following behind, 1st Hampshires† was confronted by a storm of metal and said it was ‘impossible even to reach the German front line.’93 The division’s two other lead battalions did better. Adjoining companies of 1st Rifle Brigade‡ and 1/8th Royal Warwicks,§ of 11th and 143rd Brigades respectively, found the enemy wire cut and separately fought their way into the enemy front line and the scarcely defended Heidenkopf. This group of trenches was a jot north of today’s Serre Road Cemetery No. 2 and projecting from the main German line. These battalions’ outermost companies — 1st Rifle Brigade’s right company on the ridge and the 1/8th’s left company nearer to Serre — were mostly stopped either by frontal and enfilade machine-gun fire, or both.94 Survivors from the following 1st Somerset Light Infantry¶ and 1/6th Royal Warwicks,** of 11th and 143rd Brigades respectively, pressed forward. They suffered from machine guns around Serre and in Ridge Redoubt, the 1/6th losing 80 men before reaching its own parapet.95 Some reached the German lines, but in insufficient numbers to do anything other than help consolidation.96 By 9 a.m., 11th Brigade had penetrated the German front line behind Heidenkopf on a frontage of about 600 yards and to a depth of 250–500 yards, but their early gains were already taking on the characteristics of a siege rather than an advance.97

Captain Douglas Adams, 1/8th Royal Warwicks, said the enemy enfilade was initially too high as his battalion crossed over. The triggermen soon shortened their range.98 ‘Casualties became so heavy that by the time that isolated parties had reached the German support trench (about 200 yards behind the front line) further advance was impossible.’99 It was a question of numbers. Even if 11th Brigade had forced a limited entry into the German line it was still a long way short of Hunter-Weston’s objectives and never of sufficient scale or momentum to be expanded upon.

Leutnant-der-Reserve Friedrich Stutz, RIR121, was in the Redan Ridge front line as the 1st Rifle Brigade attempted to advance:

‘The English had pushed underground tunnels [Russian Saps] forward, close to our front line. They broke the surface just before the attack and positioned Lewis guns at these. The name of the tunnel in front of us was “The Cat.” They tried to force us to keep our heads down [while the infantry crossed no-man’s-land]. A hand grenade salvo silenced the Lewis gun and we rushed forward. Reservist Fischer did great work with the bayonet. The Lewis gun is ours. Now our machine guns prove devastating to the enemy’s [infantry] columns and an artillery battery behind sends shells into them.’100

Private Ralph Miller, 1/8th Royal Warwicks, remembered ‘hundreds of fellows, shouting and swearing, going over with fixed bayonets.’101 Second-Lieutenant George Glover, 1st Rifle Brigade, said his battalion’s first wave bunched at the German wire and a ‘most fearsome hail of rifle and machine gun fire with continuous shelling opened on us. Most of us seemed to be knocked out.’102 Private Fred Lewis, 1/8th Royal Warwicks, prayed ‘to Almighty God that if I got wounded that it would be light.’103 He got his wish: a bullet pierced his left foot. His battalion commander was nearby: ‘We’d only gone over the top a few yards and he [the commander] was killed instantly — right at my side — a bullet through his head. Colonel [Edgar] Innes his name was.’ Others, wrote Lewis, were less fortunate and died slowly and in pain. ‘You’d look at them lying there all gashed, legs off, arms off, and stomach all ripped open. You’d think “Poor bugger!” and that was it. It was a matter of being used to it.’104 Second-Lieutenant William Page, 1st East Lancashires, saw some German soldiers atop their parapet waving their caps. ‘Come on English,’ they taunted, before being killed by a shell burst.105 Private John Kerr, 1st Somerset Light Infantry, reached the German trenches. A bullet grazed his head and he was taken prisoner. Among all of the carnage and death it bothered him more that his captors ‘stole our money and valuables.’106

Fourth Division, including the two Royal Warwicks battalions attached, would run up a total of 5752 casualties for 1 July, among them 1883 dead, 3563 wounded, 218 missing and 88 prisoners. Meanwhile, RIR121 recorded 179 dead, 291 wounded and 70 missing for the period 1–10 July, although mostly on the first day of that period.107 In short, for every one German casualty opposite the 4th, there were 10.7 British.

Nobody knows exactly what happened to Private Harry Woodward, 1/6th Royal Warwicks, except that he was probably killed by machinegun fire. The Birmingham teenager, whose 15th birthday was just a few weeks before he hopped the sandbags and went forward into battle, is named on the Thiepval Memorial. At the time of his death Woodward had been in France for more than a year, which meant he had been in the trenches since the age of 13. Another among 1/6th Royal Warwicks’ dead was 21-year-old Private Fred Andrews. He penned a letter to his mother in late June: ‘Do not worry I hope the war will soon be over now. Things are looking up here.’108 A few weeks later his mother wrote back: ‘Oh son I do hope you are all right. I have not had a line for nearly three weeks. . . . My own dear boy I am quite sure it is not your fault I do not know what is preventing you from writing if I could only get a line in your hand writing I should feel better.’109 Andrews is buried at Serre Road Cemetery No. 2.

Such was the noise and confusion of battle that nobody really noticed four underground German mines detonating at the head of Heidenkopf. The idea was to blow up British infantry as they entered the trenches. The mines were fired at about 7.45 a.m., some probably later in the morning. British and German sources are equally vague. One detonated as 1/8th Royal Warwicks entered the German line, two smaller mines were apparently fired as 1st King’s Own* crossed at about 9.30 a.m., while around the same time 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers had a couple of mines blown ‘under our first wave.’110 Four craters were seen after battle, but German observers shied from saying they had seen the blasts.111 Apparently the British attack ‘suddenly faltered’ near the mines, and many corpses were later found nearby.112 Quite how quadruple explosions — each with a charge of 1250–1600 kilograms (2750–3500 pounds), according to German records, and leaving a crater about 10 metres (11 yards) deep and roughly 25 metres (27 yards) across — could go unmentioned in the memoirs of so many men in the area remains unknown. The only certainty is that these four mine blasts were nowhere near as effective as had been expected.113

AT THE EXTREME north of VIII Corps, 31st Division’s attack eastwards up the exposed grassy incline leading towards Serre village and positions held by IR169 was a disaster from the outset. Thirty-first Division’s leading waves moved through their wire and into no-man’s-land at about 7.20 a.m. and lay down waiting for Zero.114 The first two waves were to advance in extended order, with subsequent ones in columns of sections.115 German shells were already bursting, soon joined by grazing machine-gun fire.116 A company of the 12th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI)† was attached to each of the 31st’s 93rd and 94th Brigades. Three sections of 210th Field Company, RE, were attached to 94th Brigade, which hoped to consolidate its gains by day, while the 93rd planned to deploy sections from 211th and 223rd Field Companies later that night.117 Five Russian Saps on the 31st’s front — north to south, John, Mark, Excema, Gray and Bleneau, the latter containing a Stokes mortar that quickly spent its ammunition when it began firing at 7.28 a.m. — were opened at 6.30 a.m. Once the attack began, the remaining two companies of 12th KOYLI were to dig these saps across to the German lines. All of the opened Russian Saps in the 31st’s sector would to some extent become havens for wounded men throughout the day.

By day’s end, the 31st had accrued about 3600 casualties, including 1349 dead, 2169 wounded, 74 missing and 8 prisoners. Opposite, IR169 sustained 141 dead, 219 wounded and 2 missing.118 That worked out at a rate of one German casualty for every 9.9 British.

In 93rd Brigade’s patch, just north of 4th Division, 15th West Yorkshires* was almost annihilated by ‘severe’ frontal and flanking machine-gun and rifle fire.119 Following, 16th West Yorkshires,† along with one company of 18th Durham Light Infantry,‡ suffered appalling casualties even before reaching their own front line. Numerous men were killed and wounded as they clambered from their assembly trenches, and still more fell as they pressed towards the British wire to begin their attack. Against the odds a small number, incredibly, made it across no-man’sland and into enemy lines, fewer still to Munich Trench immediately south of Serre and some of these, allegedly, to Pendant Copse, about a mile behind the German front line.120 Eighteenth West Yorkshires,§ coming on behind, made no headway, and incurred most of its casualties before even reaching its own wire.121 The remaining three companies of 18th Durham Light Infantry were held in reserve.

Ninety-fourth Brigade, to the north, advanced on a two-battalion frontage from trenches lacing Mark, Luke and John Copses just west of Serre. The attack of 11th East Lancashires¶ and 12th York & Lancasters** also faltered in withering machine-gun crossfire,122 as well as a heavy curtain of shellfire. That shellfire, the blasts of which Brigadier-General Rees earlier likened to poplar trees, began on the brigade’s rear-most assembly trenches and worked its way forward to the British front line.123 Twelfth York & Lancasters later reported: ‘As soon as our [preparatory] barrage lifted from their front line, the Germans, who had been sheltering in Dug-outs immediately came out and opened rapid fire with their machine guns.’124 Most of these two battalions were stopped in no-man’sland. However, up to 100 men of 11th East Lancashires surprisingly reached the ruins of Serre, only to be killed or captured there, with very few of the 12th York & Lancasters making it that far, too.125 In the wake of these battalions, the leading companies of 13th* and 14th York & Lancasters† were also fired on before reaching no-man’s-land, and were then mauled by a ‘perfect tornado’ of shell- and machine-gun fire when attempting the cross.126 Again, a very small number of men of the 14th reached the enemy line.127 It was with bloody and good reason that the 94th’s attacks were immediately suspended.128 On 94th Brigade’s extreme northern flank, the Russian Sap known as John jutted into no-man’s-land to provide northern flank protection. It was soon clogged with bloody, broken men and others sheltering from German defensive fire.

If a few isolated parties of the 31st had breached the German trenches, the overall theme was of multiple battalions effectively destroyed as effective fighting units around and behind their own front line, or as they attempted to cross the barren no-man’s-land. Supporting battalions of the 93rd and 94th all ‘suffered heavily from the German artillery barrage, which was at once put down when they made any movement and was obviously directed by observation.’129 Those small groups of survivors who miraculously made it further were all too often confronted by intact coils of German wire, sections of patchy entanglements that were essentially impassable, and gaps defended by German infantry. As 12th York & Lancasters’ war diarist bleakly noted:

In view of the fact that the enemy artillery became active as soon as it was daylight, it would appear likely that the enemy was warned of the attack by observing gaps cut in our own wire [for infantry to pass through] and tapes laid out in No Man’s Land [to aid deployment], thus obtaining at least three and a half hours warning of the attack. . . . Our intention to attack must have been quite obvious.130

He might have been writing for the whole of 31st Division, with 29th Division further south having failed for strikingly similar reasons.

Survivors of the 31st’s leading waves told of an operation that was shot into submission from the outset.131 Lance-Corporal James Glenn, 12th York & Lancasters, remembered the attackers ‘hadn’t gone but a few steps when they went down again.’132 He said the ‘funny thing about being in a barrage was being frightened and trying not to show it to your mates.’133 Corporal Douglas Cattell, 12th York & Lancasters, said he ‘never saw a German and I never fired at one. Yet all this firing was coming at us.’134 Private Alfred Howard, 15th West Yorkshires, had brazened his way to the intact German wire when a bullet smashed his rifle and he went to ground. ‘Away on the left a party of Germans climbed out of the trench, they kicked one or two bodies, any showing signs of life were shot or bayonetted.’135 After a few hours under the blazing sun surrounded by corpses, Howard bolted back whence he came. A bullet clipped his leg and he collapsed into a shell hole. ‘I got out of the hole and crawled to our line, all was quiet, except for the groans of dead and dying. You could not tell what had been trenches from shell holes, but all were full, bodies one on top of the other.’136 Most did not get close enough to the hostile parapet even to see a German soldier, let alone squeeze off a pot shot.

Those in follow-up battalions saw the grisly fate of those before them. It was with good reason that Private Tommy Oughton, 13th York & Lancasters, said he felt ‘very mixed as we waited to go over.’137 Then his battalion moved towards the British front line. ‘You could see bodies dropping here, there and wondering, is it you next?’ Nearby, Lance-Corporal Charles Moss, 18th Durham Light Infantry, saw a soldier resting a piece of raw meat on his left forearm: ‘It was the remains of his right forearm.’138 Private Frank Raine, 18th Durham Light Infantry, reached a ‘stage where you get beyond being frightened, but I felt guilty at dropping into a shell hole.’139 Lieutenant Robert Heptonstall, 13th York & Lancasters, made good distance before being wounded and going to ground. He saw a ‘dead man propped up against the German wire in a sitting position. He was sniped at during the day until his head was completely shot away.’140 Corporal Arthur Durrant, 18th Durham Light Infantry, was wounded a few paces into no-man’s-land. ‘I started dragging myself along again over bodies. Dead bodies and bits of bodies and I came to a shallow trench and I was on my back and I thought well if this is the end it is the end and that is that and I lay there looking at the sky.’141

ALL ALONG VIII Corps’ line German machine-gunners were deciding the outcome of the battle. Few British soldiers saw the muzzle flashes of those machine guns firing from the intermediate position, about 1500 yards away. But they could definitely see and hear the damage they were doing, and take an educated guess at where the welter of bullets was coming from. One soldier, at least a mile behind the front line, described the sound as a ‘tearing rattle’ within the battle symphony.142 Raine was in no-man’s-land: ‘Oh my God, the ground in front of me was just like heavy rain, that was the machine-gun bullets.’143 Private Wilfred Crook, 1st Somerset Light Infantry, was met with a ‘murderous burst’ just south of Heidenkopf: ‘I knew we were doomed. Bullets flew everywhere and dust spurted near our feet and all around as they hit the ground. Near misses in passing whispered of death, while others plucked at our sleeves or hissed and spat viciously to ricochet. The noise was deafening.’144 Private Bert Ellis, in the yet-to-attack Newfoundland Regiment, later described the fusillade tearing across the open sweeps of what is now Newfoundland Memorial Park:

No doubt you know what a noise the ‘air hammer’ makes at the dock when they are working; well, that’s something like a machine gun sounds when in action. They played havoc with our men and to make matters worse they had, practically on both sides, what is called enfilading fire, which is the worst kind of fire to be under. You could almost see the bullets coming, they came so thick and fast.145

All of these machine guns between Serre and the River Ancre had pre-registered and interlocking arcs of fire that covered no-man’s-land, as well as the British front line and the latticework of ditches behind.

‘We just had to load and reload. They went down in their hundreds,’ wrote Musketier Karl Blenk, IR169, who was among those pelting 31st Division’s infantry with bullets before Serre.146 ‘We just fired into them.’ He later surveyed the carnage: ‘There was a wailing and lamentation in No Man’s Land and much shouting for stretcher-bearers. . . . When the English tried again, they weren’t walking this time, they were running as fast as they could but when they reached the piles of bodies they got no farther.’147 Blenk was describing the killing zone, the area of no-man’sland in which the cones of fire from multiple machine guns overlapped and created a concentration of bullets essentially impassable for infantry, no matter what small-unit tactics they were using.

Wounded staggering back along the roads behind the battlefield told artillerymen of the horror. Lieutenant Frank Lushington, Royal Garrison Artillery, said he heard of ‘whole companies mown down as they stood, of dead men hung up on the uncut German wire like washing, of the wounded and dying lying out in No Man’s Land in heaps.’148

Early battle reports reaching Hunter-Weston’s headquarters at Marieux, 10 miles west of Serre, gave a false picture of events. He described these reports as ‘very rosy, to the effect that all the German front line had been taken.’149 In fact, not one report received by VIII Corps before 8.40 a.m. even suggested anything had gone wrong. But neither scandal nor cover-up was afoot. The problem lay with a confluence of factors: heavy casualties among regimental officers who normally sent the reports; delayed and intermittent communication between headquarters; and over-optimistic observers whose visibility was obscured by the smoke of battle. Hunter-Weston believed the 31st had obtained a footing in Serre, the 4th had nabbed two lines of German trenches, the 29th was through Beaumont Hamel, and X Corps to the south had snatched a vital German stronghold known as Schwaben Redoubt, near Thiepval.150 The only interpretation an optimistic Hunter-Weston could have formed on the basis of this information was that VIII Corps was progressing not quite to plan and very slowly, which was actually very different from the the disaster unfolding.

Back on the battlefield, the mechanical nature of the attack guaranteed the killing would continue. It was a point Captain Stair Gillon, 1st KOSB, later seized upon: ‘If the G.O.C. [General Officer Commanding, Major-General de Lisle of the 29th] could have flown or rather hovered over the scene for ten seconds the attack would have been countermanded. . . . But the terrible thing about war is that an attack once launched can rarely be broken off. Those in control don’t and can’t know what is going on in front.’151 So it was that several follow-up battalions in 4th, 29th and 31st Divisions were destined to repeat the tragedies of the leading battalions, despite desperate attempts to stop them.

Fourth Division headquarters told 10th and 12th Brigades to stop their infantry from crossing into no-man’s-land until a clearer picture of events was established.152 These brigades were timed to cross into no-man’s-land at about 9.30 a.m.; the message from divisional headquarters — sent in view of the manifestly heavy losses — went out at 8.35 a.m. Already there was some confusion at brigade headquarters over the flares seen rising skyward — one white flare meant the attack had been stopped, and three signalled objectives reached — and thus over how 11th and 143rd Brigades had actually performed. It was against this backcloth and with gradual realisation of the 11th’s heavy early losses that 4th Division headquarters issued its order, which began slowly filtering down the chain of command. Captain William Carden Roe, adjutant, 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers, received an urgent telephone call from Brigadier-General Charles Wilding’s 10th Brigade headquarters to stop his reserve battalion’s attack:

‘But,’ I stammered, ‘what about the white lights?’

‘Those ruddy white lights mean “Held up by machine gun

fire,” and the damned things are going up everywhere.’

The whole rotten truth suddenly dawned on me.153

Unfortunately, technology, the confusion of the day and some broken telephone links meant circulation of the divisional order did not get through in time, or at all, to the next lot of battalions pressing forward.

This tranche of 4th Division pushed forward on a combined frontage of about 1500 yards under heavy artillery and machine-gun fire from about 9.30 a.m. These battalions included 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers and 2nd Seaforth Highlanders, both of 10th Brigade, and used a blend of section columns and artillery formation.154 Also going forward were 1st King’s Own, 2nd Essex, 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers and 2nd Duke of Wellington’s, which were all in Brigadier-General James Crosbie’s 12th Brigade and all moving forward in artillery formation.155 Attempts to stop the attack of 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers* were partially successful, but some platoons went forward.156 Without exception, these became casualties.157 The kilted 2nd Seaforth Highlanders† received no word to stop its advance.158 Some of its much-depleted ranks crossed over and joined in the Heidenkopf fighting.159 Elements of the casualty-thinned 2nd Essex‡ and 1st King’s Own also defied the odds and made it into the German lines.160 Behind them, word to halt the advance reached 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers§ and 2nd Duke of Wellington’s¶ a fraction too late to stop two companies of the former and three of the latter from entering the no-man’s-land welter.161 Those who survived the passage and reached Heidenkopf participated in the fighting there.162 The remaining companies of these battalions went over shortly before 11 a.m.163 The besieged wedge around Heidenkopf now comprised the thinned-out ranks of all of 4th Division’s brigades, but there would be no more reinforcements of men and munitions for hours.

‘Our machineguns did excellent work,’ wrote Leutnant-der-Reserve Riegel, Machine-gun Sharp-shooter Troop 198.164 He was on Redan Ridge shooting head-on at 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers. ‘The entire line of skirmishers falls before us. Some try to come forward alone, but our infantry are on the parapet and mop up the individuals who come too close.’165 Lieutenant William Colyer, 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers, later grieved for friends killed: ‘I can scarcely grasp the fact that I shall never see some of them again. It is such a short while ago that I left them in the height of good spirits, and now in the freshness of youth they have suddenly gone off to another world.’166

Around this time Brigadier-General Charles Prowse, commanding 11th Brigade, stepped into no-man’s-land. He was on his way forward to get a handle on events at Heidenkopf, and probably also to arrange an attack to silence the Ridge Redoubt machine-gunners. He did not get far. A bullet slammed into his stomach. He died a few hours later in a medical station and is today buried at Louvencourt Military Cemetery. Across VIII Corps’ battle front, nine battalion commanders were killed or died of wounds, and nine more were wounded.167 Casualties among junior officers and NCOs were alarmingly heavy, which meant organised command and control within the British lines quickly began to fragment, and even more so in the Heidenkopf toehold.

On the south side of Beaumont Hamel, Major-General de Lisle now committed Newfoundland Regiment* and 1st Essex,† both in Brigadier-General Douglas Cayley’s 88th Brigade. It was 8.37 a.m., and de Lisle wrongly believed the advance by its infantry was only temporarily held up and that parties of its infantry were fighting in the German trenches.168 Major Richard Spencer-Smith, second in command of reserve battalion 2nd Hampshires, considered the attack a ‘grave error of judgement, being preordained to failure and having no chance of success.’169 German machine-gunners were in no way subdued.

First Essex was initially delayed; communication trenches were clogged with casualties. The Newfoundlanders advanced overland in columns of sections at 9.15 a.m. As Private Walter Day, Newfoundland Regiment, later said, ‘We knew we were in for it. Everybody knew we were in for it.’170 Within 30 minutes, the battalion lost 233 men dead, 386 wounded and 91 missing.171 Attacking from trenches well behind the front line, mostly north of today’s memorial park, many Newfoundlanders were felled long before entering its present-day grounds. Others made it into noman’s-land and proceeded down the long incline towards Y Ravine. One said the ‘air seemed full of hissing pieces of lead all bent on the same grim errand. Our comrades began to fall all round us, and now a man stood alone where before a section had stood.’172 First Essex came up 40 minutes later, deployed in columns of sections and attacked.173 It, too, failed in a storm of artillery and machine-gun fire. ‘The fire was hellish and many men were not able to get back from No Man’s Land until twenty-four hours after the attack died down,’ wrote Captain George Paxton, 1st Essex.174

Divisional headquarters learned of these disasters at about 10 a.m., and five minutes later de Lisle, who now had a better handle on the fate of his division, wisely decided no more of the 29th should be sent forward.175 It was too late; most of the killing had already been done.

Hunter-Weston’s rose-tinted knowledge of events abated alongside worsening situation reports, but his outlook remained upbeat. At about 10.25 a.m, he ordered the 29th’s 4th Worcesters* and 2nd Hampshires,† along with the rest of the 4th’s 10th Brigade — 1st Royal Warwicks and 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers — to renew the attack at 12.30 p.m. and take Beaumont Hamel and the German intermediate line, or Munich Trench, behind it. This was far too optimistic, but revealed Hunter-Weston knew his corps had no hope of reaching its final objective, Serre–Grandcourt Spur.176 He contemplated using 48th (South Midland) Division, and brought it up to Mailly Maillet. A 12.30 p.m. rush forward by 1st Lancashire Fusiliers was gunned down. The 88th’s part in the planned operation was delayed, postponed and finally cancelled at 1.45 p.m. In the 10th’s sector, between about 1 p.m. and 2 p.m., attempts by a strong patrol from 1st Royal Warwicks‡ and then a company of 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers§ to cross the British front-line trenches into no-man’s-land faltered under intense machine-gun fire.177 At about 2.55 p.m., Major-General Sir William Lambton, 4th Division’s commander, told VIII Corps his division had suffered too many casualties to attack again.178 Casualties, confusion and communication and organisational difficulties saw the 10th’s part in the planned attack postponed and then abandoned mid-afternoon.179 Hunter-Weston now reflected on events: ‘The result of the day’s fighting up to the present 3pm has been disappointing. We have gained very little ground & our hold on what we have got is precarious. It is very probable that the result of the VIIIth Corps attack will be that we shall find ourselves back on our original line.’180 Regardless of this midafternoon epiphany, Hunter Bunter was not quite done yet. His profligate thoughts returned to Serre and 31st Division.

Just after midday, Brigadier-General Rees’ 94th Brigade was ordered by Major-General Robert Wanless-O’Gowan, commanding the 31st, to attack and confirm the British footing at Serre, which was behind enemy lines.181 Rees suggested postponing until more detailed information on the situation could be gathered, implying he had nil appetite for any operation of the type suggested.182 Wanless-O’Gowan was back in touch at about 5.20 p.m. asking Rees and Brigadier-General John Ingles, of the 93rd, if they were arranging an operation to establish communications with ‘our troops in Serre.’183 Wanless-O’Gowan — almost certainly at Hunter-Weston’s behest — offered up some fresh troops. Rees and Ingles rightly opposed any such endeavour, as their brigades were not ‘in a fit state,’ which was a polite way of saying they had been shot to pieces.184 Rees doubted whether any British troops were in Serre, barring the dead and prisoners. This seemed to be supported by the latest Royal Flying Corps observation report.185 Wanless-O’Gowan listened to his men on the spot. He told Hunter-Weston their concerns and proposed using his 92nd Brigade to hold the front line in case of a German counterattack, and suggested a prepared operation on 2 July with fresh troops might be a better course of action.

Hunter-Weston seized upon Wanless-O’Gowan’s suggestions even though he knew all was not going remotely well. At 6 p.m. he ordered the 92nd forward for a two-battalion attack at 2 a.m. on 2 July to clear up ‘the situation’ in Serre.186 Almost four hours later, Hunter-Weston realised the folly of this operation — one wonders exactly how much politely worded lobbying from his subordinates was required — and cancelled it.187 Hunter-Weston had finally conceded defeat, seven hours after stating that it was the most likely outcome of the battle for VIII Corps.

From Soden’s mid-morning perspective the fighting between Serre and Beaumont Hamel had gone mostly to plan. Reports arriving at his Biefvillers headquarters led him to identify 36th (Ulster) Division’s unexpected and troubling break-in around Schwaben Redoubt (fully discussed in Chapter 6, which deals with X Corps’ operations) as a priority. Soden realised that the loss of this ground posed a significant threat to the tenability of his divisional sector if left unchecked. Comparatively speaking, the tactical situations around Ovillers, further south and also in his divisional sector, and in the Beaumont Hamel–Serre area, to the north, were under control. Other reports would have told him that RIR119’s and RIR121’s co-ordinated defences were broadly functional and had mostly blunted the enemy’s attacks within one-and-a-half hours.188 The Hawthorn Ridge break-in was obviously minor and already fading. The wedge of land yielded around Heidenkopf had been contained and was being gradually squeezed out by organised counterattacks that began late morning. By about 9 a.m., Soden knew his on-the-spot commanders were controlling the battle between the River Ancre and Serre, and that he could focus his attention on remedying the tenuous and troubling situation at Schwaben Redoubt.189

‘EVERY BATTLE HAS shown that trenches which are either lost or in dispute may be comparatively easily cleared or recaptured, when this is undertaken immediately,’ said Generalleutnant Hermann von Stein, XIV Reserve Corps’ commander.190 ‘I expect leaders to show the greatest determination and initiative in such cases.’ So it was that the third and final act of the day, the German reclamation of ground lost to Hunter–Weston’s Corps, was set in train.

It began at about 10. a.m. on Hawthorn Ridge, where a small group of 2nd Royal Fusiliers, joined by some men of 16th Middlesex, had held the crater rim nearest the British lines for almost three hours, while German infantry occupied the other side. British and German machine-gunners and riflemen traded shots from opposite sides. A few of the up to 120 men of the 2nd Royal Fusiliers who made it there had even entered the trenches of RIR119, engaging the enemy with bayonet, grenade, rifle and pistol. It was always a one-outcome battle. For those fusiliers who chanced a look back at their own lines, the sight was of 86th Brigade’s main attack being clinically gunned down, which meant they would be neither reinforced nor supplied with ammunition.191 Moreover, they were outnumbered and casualties were increasing. As small, well-armed RIR119 counterattack groups worked in from each flank, this casualty-depleted, beleaguered group of British soldiers was gradually pushed back; they retreated to the crater before survivors ran a gauntlet of machine-gun fire as they dashed away overland. Few made it back. By 10.30 a.m., the crater on Hawthorn Ridge was lost for good, meaning 29th Division had failed to make a single lasting gain.

Private Noel Peters, 16th Middlesex, watched a blood-covered soldier of 29th Division race back towards safety amid the no-man’s-land fusillade. Occasionally he stumbled, fell, picked himself up and continued on. ‘And then he took a run and a dive and landed on the parapet. We grabbed his arms and hauled him over. . . . He kept patting his legs to see where he was hit. “I don’t know, I think they got my legs.” But do you know what? He didn’t have a scratch on him.’192

One-and-a-quarter miles away at Heidenkopf, 4th Division’s breakin quickly took on the characteristics of a smaller-scale trench raid. During the day soldiers from some nine battalions found their way to the German trenches here and beyond, but probably no more than about 1000. Effectively, the break-in had taken three successive trenches of the enemy front-line system on a 600-yard frontage. Men from different units were mixed up, officer and NCO casualties were heavy, and nobody really knew the layout of the heavily shellfire-damaged German trenches. In places consolidation had got underway quickly, in others not. One critic later said those in Heidenkopf had not grasped the ‘difference between a battle and a raid.’193 He meant that order had not been imposed upon chaos and that the captured trenches were never really made fit for defence against the organised counterattacks that were certain to follow.

The initial German fightback was implemented by on-the-spot NCOs and subalterns of RIR121. Patrols probed for weak spots in the British perimeter, and bombing parties began concentric counterattacks, both along trenches and overland.194 Soon the regiment’s commander, Oberstleutnant Adolf Josenhans, ordered more counterattacks without delay.195 His junior commanders led small, well-armed groups of infantry — usually 10–20 men, sometimes more — who worked from one corpse-littered trench bay or shell hole to the next. Supplies of grenades and bullets were brought up behind them. Where required, company- and battalion-sized units were applied to the job. The Rifle Brigade’s historian said an ‘attempt was made to hold out in the German second line [of the front line system]; but the German supply of bombs was apparently inexhaustible, and after fifteen minutes, this was found to be impossible.’196 Josenhans committed his regiment’s 3rd Battalion piecemeal: ‘Step-by-step the tenacious enemy was pushed back. Again and again they barricaded themselves with sandbags with a machine gun or mortar, so it was hard to get at them with grenades.’197 By 11 a.m. the most advanced 4th Division parties had been driven from Munich Trench, and by 5 p.m. ‘all that could be retained was the trench [150–200 yards in length] across the base of the Quadrilateral [Heidenkopf]. Blocks were made.’198 By dusk, several hours later, the British had been forced back into the Heidenkopf trenches.199 The struggle continued into the night and, barring one company of 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers that went over that night and held out until about noon on 2 July, the bridgehead was eventually yielded around midnight as the last defenders stole away.

Sergeant Arthur Cook, 1st Somerset Light Infantry, recalled the chaos as officers and NCOs tried to organise the Heidenkopf defences.200 ‘Jerry was popping up all over the place, behind and on our flanks and throwing grenades at us from all angles.’ Somebody panicked and 400–500 men bolted, at first in dribs and drabs. Drummer Walter Ritchie, 2nd Seaforth Highlanders, stood in plain view atop the parapet and repeatedly bugled ‘Charge’, which stemmed the flood. Ritchie, a professional soldier, won the Victoria Cross for this, and for carrying messages over fire-swept ground. He lived. The situation remained touch and go. Cook’s group collected grenades from the dead but soon these were spent. ‘The Germans then gradually drove us back inch by inch, through their superior supply of bombs.’ The uninjured trampled over the dead and wounded. Bombs were scarce, as was water. ‘Jerry took advantage of the maze of communication trenches to follow up every yard we gave.’ Soon all that remained in Cook’s immediate area was a stretch of the old German front line, held by about 50 parched soldiers. ‘Shells were now falling thick and fast, the enemy had apparently retired and asked for artillery support to try to dislodge us.’ It worked. Shortly before midnight, Cook’s party withdrew, stumbling over corpses and into shell holes. ‘How I escaped I do not know.’

Leutnant-der-Reserve Emil Geiger, RIR121, was thinking much the same as he led a counterattack group into Heidenkopf that afternoon. ‘I seemed to be invincible on this day.’201 All around him men were killed — an NCO shot in the heart, two just-arrived reinforcements shot through the head, along with plenty of others killed or wounded in the fighting. ‘We ran into English machine-gun fire at a distance of a few metres. Two of my men were almost torn to pieces. I was, strange as it may sound, unscathed.’ Geiger continued: ‘We attacked the enemy concentrically using our grenades and they had to withdraw from traverse to traverse. We had very heavy losses.’202 Here and there the resistance firmed, and Geiger’s group had to consolidate their gains. ‘We were forced to put a barricade between us and the enemy, sandbags on top of our dead friends and enemies.’ That night the trenches were back in German hands. Geiger was ‘quite exhausted by the excitement of the day, apathetic and [cradling a] half dislocated arm through the many throwings of hand grenades.’ Earlier that afternoon, a parched Leutnant-der-Reserve Friedrich Conzelmann, RIR121, guzzled greedily at his water bottle: ‘The sun shone so beautifully over the slaughter of 1 July. The heat beating down on us was such that we nearly died of thirst.’203

German soldiers returning to Heidenkopf described it as a charnelhouse. One said British and German dead lay heaped up in piles of five or six, all horribly mutilated by hand-grenade blasts.204 Another said about 150 German soldiers lay dead in the trenches — witnesses said their bodies ranged from severely mangled to badly charred — and at least three times as many British.205 The scene of carnage around RIR121’s positions spilled into no-man’s-land where about 1800 British soldiers lay.206 ‘The lines of English dead,’ wrote one German eyewitness, ‘are like tide-marks, like flotsam washed up on the sand.’207

Eighth Corps’ bloody destruction north of the River Ancre was guaranteed before a single man stepped into no-man’s-land. The sevenday bombardment’s failure was compounded by the botched timings of the Hawthorn Mine blast and initial barrage lift. German defenders had up to 10 minutes’ warning to meet an attack from their battered but defensible network of trenches, redoubts and fortified villages, with help from multiple operational artillery batteries. Unsurprisingly, numerous British battalions were destroyed behind and around their own front line, as well as in no-man’s-land. This was exactly as Soden had planned. The mechanical nature of the attack — despite efforts to stop it in places — only added to the slaughter. Fourth Division’s Heidenkopf epic was destined to fail, as was the 29th Division’s toehold at the Hawthorn Ridge crater. The few men of 31st Division who made it to Serre proved to be red herrings who enticed profligate Hunter-Weston towards ill-considered salvage operations even after he had admitted any hope of success was lost. By contrast, in a division-wide context, Soden’s regiments, defensive line and counterattack scheme north of the Ancre had performed as he expected. From an early hour, as we shall see in the next chapter, he was able to rely on his men on the spot to organise the defence and counterattacks, and focus his attentions, reserves and artillery on erasing X Corps’ very troubling break-in at Schwaben Redoubt, near Thiepval. In short, Hunter-Weston’s pre-battle blunders had handed Soden the tactical advantage and victory over VIII Corps. The tactical ramifications of this quickly extended south of the meandering waterway and affected the outcome of the neighbouring X Corps’ operation.

A SWATHE OF lumpy ground and a ditch half filled with rotting leaves in what is today known as Sheffield Memorial Park, near Serre, are all that remain of the front-line trench from which 94th Brigade set out. Few got far beyond this defile, which edges a stand of trees that in 1916 was known severally as Mark, Luke and John Copses. Nowadays the park holds a handful of stone memorials and ageing plaques. In December 2014 it is muddy and cold, and several of the memorials are draped with British north-country football tat and made-in-China wreathes with fading poppies. It was somewhere near here that war poet Sergeant John ‘Will’ Streets, 12th York & Lancasters, was wounded then killed while trying to rescue a wounded soldier. Some of his verses were probably roughed out in these trenches, as he explained: ‘They were inspired while I was in the trenches, where I have been so busy that I have had little time to polish them. I have tried to picture some thoughts that pass through a man’s brain when he dies. I may not see the end of the poems, but hope to live to do so.’208 The 31-year-old is thought to be buried in Euston Road Military Cemetery, which back in the day probably was not all that different from another soldiers’ plot that Streets saw not long before his death:

When war shall cease this lonely, unknown spot,

Of many a pilgrimage will be the end,

And flowers will bloom in this now barren plot,

And fame upon it through the years descend,

But many a heart upon each simple cross,

Will hang the grief, the memory of its loss.

FROM HIS POSITION on the outskirts of Serre, Unteroffizier Otto Lais, IR169, saw successive lines of 31st Division’s infantry advancing into a swarm of bullets from multiple chattering machine guns. Belt after belt of gleaming Spandau ammunition clattered through Lais’s weapon; its water coolant boiled and piping-hot barrels were repeatedly changed. The gun’s steam overflow pipe broke loose: ‘With a great hiss, a jet of steam goes up, providing a superb target for the enemy. It is the greatest good fortune that they have the sun in their eyes. . . . We fire on endlessly.’209 Soon the water ran out. Lais’s mates urinated in the coolant container as an alternative. Ammunition stoppages were cleared. He saw British soldiers go to ground, hiding behind the dead and wounded. ‘Many hang, mortally wounded, whimpering in the remains of the barbed wire.’210 All told, his gun loosed off about 18,000 rounds, and another nearby about 20,000: ‘That is the hard, unrelenting tempo of the morning of 1st July 1916.’211 Lais continued: ‘Skin hangs in ribbons from the fingers of the burnt hands of the gunners and gun commanders! Constant pressure by their left thumbs on the triggers has turned them into swollen, shapeless lumps of flesh. Their hands rest, as though cramped, on the vibrating weapons.’212 Using those same hands, Lais, the killer, later became an artist known for his brush and charcoal celebrations of women and sexuality.

‘Impressions came back later, in flashes, very clear, like photos,’ said Private Alfred Damon, 16th Middlesex. ‘But then? No, nothing.’213 He remembered that soldiers of 29th Division advanced with tin triangles fixed to their haversacks, which meant British observers could see them more clearly from a distance. Now he could see those ‘tin triangles glittering in the sun’ on the backs of the numerous dead.214 Soon enough, Damon’s platoon hopped the bags, and after about 100 yards a bullet thudded into his shoulder.215 The former public schoolboy did not like swearing, said he had had a pious upbringing.216 With bullets and shrapnel flying those values did not seem to matter so much. ‘I let go with a stream of filthy language; words that would have made a Cockney Eastender blush. I suppose I must have heard all those words and retained them in my subconscious mind.’217 He crawled back to the British trenches and then to a dressing station where he met a blood-covered friend whose scalp had been creased by a bullet: ‘The only thing he told me about it was that the impact was so great that he thought he was dead. I remember being surprised that a person’s thoughts can travel at such speed between the impact of the bullet and unconsciousness.’218

Damon was quite likely one of the soldiers in Lieutenant Malins’ film of the attack across the Beaumont Hamel–Auchonvillers road. At the time a somewhat detached Malins was watching shells burst, listening to the swelling machine-gun fire and worrying whether his camera’s lens was clean:219 ‘I looked upon all that followed from the purely pictorial point of view, and even felt annoyed if a shell burst outside the range of my camera. Why couldn’t Bosche put the shell a little nearer? It would make a better picture. And so my thoughts ran on.’220 This was Malins at his most high-handed. Soon enough a chunk of German shrapnel cleaved his tripod leg, which Malins fixed. A few hundred yards away through the viewfinder he saw shellfire doing the same thing to men, except that they were not quite so easily repaired and returned to action.

‘This certainly provided me with what would be called a traumatic experience,’ wrote Private William Slater, 18th West Yorkshires, of advancing from a trench 500 yards behind the British front line opposite Serre.221 He saw men hit by machine-gun bullets fall in a ‘curious manner,’ and sheltered in a shell crater with others, most likely still behind British lines. As explosive shells blew and shrapnel whirred, he pondered his own mortality:

What would it be like to be obliterated like an insect under someone’s foot? Would there be a sudden blackness like the switching off of a light, and if so would it continue forever, and in that case how should I know that I was dead? Although I was not unduly afraid of being killed outright, I certainly shrank from the possibility of being grievously wounded and left there to die in agony.222

Leutnant-der-Reserve Adolf Beck’s memories were mostly of soldiers dying horrible deaths. The RIR121 officer saw British soldiers cut down by machine guns ‘as if by mowing machines,’ and by the explosion of ‘diabolical’ shells that penetrated the soft ground before detonating.223 One explosion sent bodies flying in all directions. One of the victims, a tall Scot, came down on an iron stake and ‘was spitted straight under his lower jaw. Thereafter I was faced with the gruesome sight of a death’s head staring at me.’224 Beck soon found that his observation post, near Heidenkopf, was behind enemy lines. A British soldier called out ‘Germans?’ into the darkness of its entrance — as if he was ever going to get an answer — and tossed two hand grenades down the stair well. ‘They exploded wrecking the timber and doing my hearing no good.’225 At dusk, Beck slipped past some British outposts until he linked up with other soldiers of RIR121. Soon enough Heidenkopf was retaken and Beck found himself among an exhausted group of German soldiers: ‘Sitting amongst comrades from the other companies, tired out and emotionally drained, were the remnants of my 3rd Company — thirty men and five Unteroffiziers. They slumped there, dog tired and spent. It had all been too much!’226

Private Francis ‘Mayo’ Lind of Little Bay, Newfoundland, was not so lucky. The nickname ‘Mayo’ came after he complained about a shortage of tobacco of that brand at the front,227 in one letter among a bunch of his published in a Newfoundland newspaper. The community rallied; the boys at the front were inundated with tobacco.228 In 1916 it was a patriotic act — not so now — and made Lind something of a Newfoundland celebrity. On 29 June he promised to send ‘a very interesting letter’ soon.229 But, just before 9 a.m. on 1 July, Lind’s promise was about all used up. He was killed in what is now Newfoundland Memorial Park, probably by machine-gun fire. Someone saw him ‘doubled up as though he had been hit in the stomach.’230 The affable 37-year-old with pale blue eyes and a boyish turn of phrase was gone. Newfoundland had lost its most famous war scribe. Years later, Lind’s body and that of another Newfoundlander were found and buried together at Y Ravine Cemetery in the memorial park. Lind’s cryptic epitaph on the shared headstone: ‘How closely bravery and modesty are entwined.’

THREE DAYS AFTER the battle, Hunter-Weston penned a farrago of fiction and fact for his soldiers.231 It was rich with the adjectives of heroism and the word ‘failure’ was conspicuous for its absence; it was not something he would publicly admit to. Instead he wrote of the ‘splendid courage, determination and discipline’ of his divisions and of the glorious dead who had ‘preceded us across the Great Divide.’ The next part of his message was mostly a lie: ‘By your splendid attack you held these enemy forces here in the North and so enabled our friends in the South, both British and French, to achieve the brilliant success they have.’ The British and French had certainly made gains well south of the Albert–Bapaume road, but Hunter-Weston was very obviously seeking to divert attention away from the tragedy that had befallen his corps. He knew full well that VIII Corps’ job was never to provide any kind of diversionary attack for the areas where gains had been made, but rather to provide flank support for Fourth Army’s main thrust around the Albert–Bapaume road.232 In brief, his message was a paean to the virtues of duty and gallantry, and was designed to dress his failure as something it never was, a success.

Hunter-Weston’s semi-literate letters to his wife reveal much of the man behind the façade. ‘Our attack, though carried out with wonderful gallantry, discipline & determination failed to get home, & though we inflicted heavy losses on the enemy, our losses also were severe, & we are still in our old positions.’233 Privately, he could admit his corps’ failure, but he was incapable of accepting responsibility for having set the tactical parameters of battle in favour of the enemy. He was disappointed that his corps’ ‘splendid preparations, excellent discipline & magnificent courage in attack, have not had the result we all hoped for.’234 In Hunter-Weston’s mind it was better to veil the big picture of catastrophe with the adjectiverich language of heroism, propped up with the crackpot eugenics of his message to the troops: ‘It was a magnificent display of disciplined courage worthy of the best traditions of the British race.’235 If casualties held no importance to Hunter-Weston in victory, he attached some higher moral value to them in defeat; in this logician’s mind, anything could figure as anything else.