CHAPTER 7

Ovillers, La Boisselle or Bust

III Corps’ charge into the valleys of death

‘They flung everything at us but half-croons. . . . I saw one lad putting his hands in front of his face as if to shield himself from the hail.’1

— Private Jimmy McEvoy, 16th Royal Scots

‘NO INDICATION THAT Ovillers, Contalmaison or La Boisselle had been captured,’ wrote Major Lanoe Hawker, VC, of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), after a midday sortie over the battlefield. In the cloudless sky above the shell-pocked Albert–Bapaume road Hawker spied twin mine craters, one on either side of the carriageway, near the ruins of La Boisselle. The Y-Sap crater to the north was clear of British infantry, but, from his lattice-tailed DH2, Hawker observed minor gains around the chalkstone jaws of the massive Lochnagar cavity. ‘Many dead lying on the Eastern slopes [of Sausage Valley] outside this crater,’2 wrote the pilot who was commander of 24th Squadron.

Five hours earlier, Lieutenant Cecil Lewis, 3rd Squadron, RFC, had been 8000 feet above the old Roman road that runs between Albert and Bapaume. At 7.28 a.m. Y-Sap mine blew with a heave and flash, vaulting an earthen pillar some 4000 feet into the air. ‘A moment later came the second [Lochnagar] mine. Again the roar, the upflung machine, the strange gaunt silhouette invading the sky.’3 Through the mist and smoke Lewis watched the British barrage lift off the German trenches and lines of khaki-clad infantrymen of III Corps move forward. It had begun.

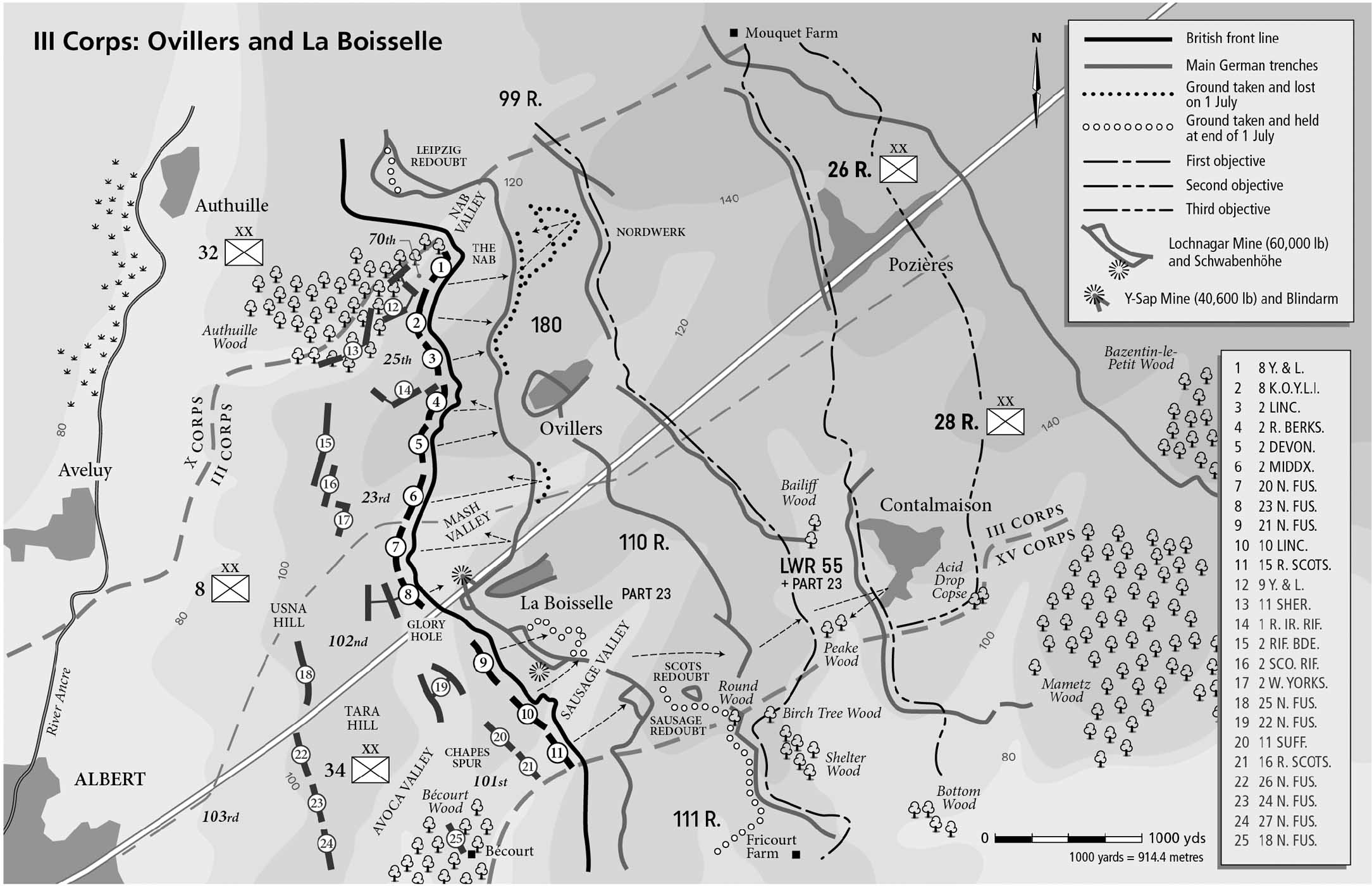

A pilot flying overhead might have likened this part of the battlefield to the splayed fingers of his left hand, the digits being spurs and the gaps between valleys. Today, looking towards Albert from outside Ovillers Military Cemetery, you are standing just below the crest of Ovillers Spur, the middle finger. Off to the immediate left — beyond the scoop of Mash Valley and the die-straight highway — is La Boisselle Spur, the ring finger. Beyond that swell are Sausage Valley and then Fricourt Spur, the little finger. Over to the right, hidden by the summit of Ovillers Spur, are Nab Valley and then Thiepval Spur, which is the index finger, with Leipzig Redoubt at its tip. Thiepval sits in the crook between that finger and your thumb.

Twenty-sixth Reserve and 28th Reserve Divisions’ trenches, redoubts and strongpoints crisscrossed the spurs overlooking III Corps’ approach routes from the lower ground towards Albert, and blocked off the grassy valleys in between. The 26th’s Infantry Regiment 180 (IR180) held the trenches from Ovillers north to Leipzig Redoubt, while the 28th’s Reserve Infantry Regiment 110 (RIR110) defended the ground between La Boisselle and Fricourt Spur. Machine-gunners in Ovillers and La Boisselle covered Mash Valley with formidable defensive firepower. South of La Boisselle, a swell of ground known as Schwabenhöhe dominated the approaches to that village and, along with Sausage Redoubt, those to Sausage Valley. A series of trenches 1000–1500 yards beyond were designed to scotch any break-ins, as was the intermediate line proper, about the same distance back again and running from Mouquet Farm to Pozières and thence to Contalmaison. In between, Nordwerk and Mouquet Farm Redoubts covered the area north of Ovillers, while Scots Redoubt supported Sausage Redoubt and La Boisselle. A second position, 1500–2000 yards further back again, prevented access to Pozières Plateau on the main ridge. These defences conformed to the ground and were formidable; forcing them would require careful application of thought, artillery and infantry.

The task fell to Lieutenant-General Sir William Pulteney, whose corps command owed more to seniority than either professional or intellectual ability.4 He had served in Egypt and Northern Ireland before the war, with stints in Uganda, Congo and South Africa suiting this marksman’s taste for big-game hunting. By 1916 ‘Putty,’ a peaceful country squire in appearance,5 had advanced well beyond his limited abilities thanks to the wartime demand for experienced senior officers. The 55-year-old Eton alumnus had attended neither Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, nor Staff College, which explained why he lacked the professional skillset of his peers and was probably the basis for his reputation as a bungler. One officer thought him the ‘most completely ignorant general I served during the war.’6 General Sir Douglas Haig had this to say about Pulteney in May 1916: ‘He seemed very fit and cheery. But after listening to his views on the proposed operations of his Corps, I felt he had quite reached the limits of his capacity as a commander. A plucky leader of a Brigade or even a Division, he has not however, studied his profession sufficiently to be really a good corps commander.’7

The story goes that talented staff officers were appointed to III Corps to offset Pulteney’s muddling, which was all about ill-thought-out operations and buck-passing when they turned sour.8 Eventually it would get him sacked, but not until 1918. Later he served as Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, and his 1941 obituary said he had never been ‘known to make a mistake in the ritual and ceremonies of Parliament.’9 Pulteney’s bent for ‘ritual and ceremonies’ was all about hiding behind a mask of competence.

Pulteney planned to break the Ovillers and La Boisselle stronghold with a frontal and uphill assault towards Pozières Ridge. Success here was central to Haig’s strategy, and would open the way to Bapaume then Arras for the cavalry, and then the infantry of General Sir Hubert Gough’s Reserve Army. Failure would bust Haig’s Somme plans. Pulteney committed two whole divisions to the attack: the 8th and the 34th, with 19th (Western) Division in corps reserve. Third Corps had a total nominal strength of 94,460, but the estimated number of infantrymen actually involved in the battle, along with elements of various other units, was about 16,700.10

Mash Valley, which holds the Albert–Bapaume road, was the demarcation line between the two attacking divisions, the 8th’s area being to the north and the 34th’s to the south. They were to advance to a total depth of 2500–3700 yards behind the German front line. The 34th, its infantrymen wearing yellow-coloured triangles on their backs so they could be seen by observers, would attack in four distinct columns. Its 101st and 102nd (Tyneside Scottish) Brigades formed the vanguard, followed by 103rd (Tyneside Irish) Brigade.11 To his credit, Putty opted to try to pinch off the salient at the head of La Boisselle Spur, with the two columns of the 102nd taking it and the village that sat atop it from either side. There were two big mines in the 34th’s sector to help its infantry: Y-Sap and Lochnagar mines respectively totalled 40,600 and 60,000 pounds.12 Y-Sap mine was to erase the Blindarm, a small grouping of German trenches overlooking Mash Valley, and Lochnagar was to obliterate the strongpoint Schwabenhöhe overlooking Sausage Valley and no-man’sland. By contrast, the 8th was spread out over a much wider frontage, with its three brigades — north to south, the 70th, 25th and 23rd — attacking abreast. While some of the 8th’s and 34th’s lead battalions would attack directly up Ovillers and Fricourt Spurs, most were condemned to advance along the death traps of Mash, Sausage and Nab Valleys.

Everything hinged on the ability of III Corps’ artillery to shell the German positions and resistance into submission. Pulteney had a comparatively rich concentration of artillery that included 98 heavy guns and howitzers, or about one to every 40 yards of attack frontage, and about 175 field guns, or roughly one to every 23 yards.13 A dozen attached French guns would fire gas shells. But there were significant problems with the artillery’s pre-battle work: too many dud shells, a lack of ammunition and shellfire diluted over a wide area undermined its efforts to break down German defences and resistance, both in the front line and further back.14 Moreover, Pulteney did not have anything like the number of guns required to produce a German collapse and open the way for Gough’s army. His own gunners warned that their attempts to cut the enemy’s more distant wire defences would likely be unsuccessful.15 Even so, Ovillers and La Boisselle were razed, trenches collapsed and wire was mostly pared away. As one German soldier said, ‘Whoever went above [ground] as a sentry could barely still recognise the position. Instead of well-developed trenches he saw one crater alongside another; the last wall remnants of La Boisselle became crushed into powder in these days of innumerable shells.’16 Yet, even as a pulverised warren, the Ovillers and La Boisselle moonscape was defensible by German soldiers who were holed up in dugouts and listening to muffled explosions 30–40 feet above. They just had to race up from their bunkers, take positions in the shellfire-torn wasteland and open fire.

None of this squared with Pulteney’s belief that the ruined villages and Schwabenhöhe would be untenable and the enemy wiped out.17 Not everyone agreed. Lieutenant-Colonel John Shakespear, 18th Northumberland Fusiliers,* was well aware that La Boisselle’s garrison was ‘very much on the alert.’18 Lieutenant-Colonel Godfrey Steward, 27th Northumberland Fusiliers, was astounded by the optimism at Pulteney’s headquarters: ‘Their Intelligence must have been atrocious.’19 Captain Reginald Leetham, 2nd Rifle Brigade,† said the bombardment of Ovillers was impressive, but pondered whether it was ‘doing us much good’ given that most German soldiers were safe underground.20 Major James Jack, 2nd Scottish Rifles, also doubted whether German infantry in Ovillers had been cowed.21 While Pulteney optimistically believed the bombardment was fit for purpose, several battalion and company commanders whose men would be involved in the attack held significant doubts.

As it turned out, German morale withstood the bombardment, which caused few casualties. The 2570-strong RIR110 had anticipated the attack after ‘long days and nights of unbearable tension.’22 One soldier claimed he felt ‘extreme joy that the deep dugouts constructed by us with hard work also protected us against the heavy calibre shells.’23 Another said British hopes that life in the German trenches would be extinguished were ‘very false.’24 One officer in the roughly 2800-strong IR180 alleged that the mood in its dugouts was ‘exceedingly’ encouraging:25 ‘The bombardment can’t last for too long; we expect the attack from one day to another.’ Another officer, Oberleutnant-der-Reserve Heinrich Vogler, IR180, recalled nearly 55 years later that while his ‘men’s mood was low,’ they were not lacking in ‘courage or determination.’26 So it was that the soldiers of IR180 and RIR110 waited deep underground, with rifles to hand and the flickering light of candles playing across their stubbly faces as they waited to exact bloody payback.

These soldiers knew full well that the British attack would begin early on 1 July. Late on 30 June, an underground Moritz listening device in the La Boisselle salient had intercepted a British message suggesting the attack was due the next day.27 This news was forwarded to Second Army and thereafter circulated among front-line regiments, which notified their companies two to three hours before Zero.28 As Schütze Christian Fischer, a machine-gunner in IR180 opposite the increasingly splintered ruins of Authuille Wood, remembered:

Early in the morning of 1 July word filtered through to us that the enemy would attack that morning. . . . Some of us said the English would attack at 7.30 a.m. At 5.30 a.m. the Vizefeldwebel stood at the dugout entrance and waited for the enemy’s attack, while we stood ready with our guns in the dugout. We all looked at the clock and waited anxiously for the enemy attack. We wanted to get back at the Englishmen.29

Those brave lookouts who ventured up into the trenches found them destroyed, wrote another soldier, but across no-man’s-land ‘everything was full of life and the British trenches were a mass of steel helmets.’30 Most everyone had an ear cocked for the audible moment when the British shellfire moved further back, confirming the infantry attack was beginning.31

From 6.25 a.m., III Corps’ artillery and mortars spiked to a crescendo, raining shells onto the German front line. The barrage should have been maintained consistently until Zero or, as Brigadier-General John Pollard, 25th Brigade, preferred, co-ordinated with the attacking infantry.32 That would at least have forced enemy soldiers to remain underground while Pulteney’s crossed no-man’s-land. It did not happen. After just 35 minutes the heavy guns stepped their fire back, leaving only the field artillery’s lighter shells to play over the German front trench until 7.30 a.m.33 This dilution of shellfire gave Württemberg and Baden soldiers further notice, and ample time to rush some men into ground-holding positions. Several German machine guns began firing at 7 a.m.34 Twenty-eight minutes later the mine blasts sent shock waves pulsing through the subterranean German city, and two minutes later the field guns lifted their fire further back.35 This confluence of factors pinpointed the attack almost to the minute. At 7.30 a.m., ‘The Swabians poured forth out of every mined dugout. The trench was barely still able to be recognised, but each man, each group, each platoon knows their place and their defensive field. Nestled behind the destroyed breastworks and in shell craters, they awaited the superior strength of the approaching enemy.’36

Worse still, 26th Reserve and 28th Reserve Divisions’ artillery in this area was far from destroyed. In nominal terms the 26th had at least 29 guns directly supporting the Ovillers sector and providing close defensive fire for IR180, plus a further 28 nearby that could shoot into this area if needed. Divisional commander Generalleutnant Franz Freiherr von Soden had insisted on preserving his limited artillery resources through fire restraint, which meant many of his batteries went undetected by RFC and artillery spotters, and survived counterbattery shoots. A large portion remained intact, concealed and good to open defensive fire when the British attack began. Generalleutnant Ferdinand von Hahn’s gunners in the 28th had not shown the same restraint. Many of its estimated 60 barrels behind La Boisselle and the summit of Fricourt Spur had been knocked out, leaving an estimated 42, of which many were apparently useless.37 But Hahn’s guns in this part of the line remained capable of supporting the front-line infantry, according to British battle accounts,38 although never to the same extent as Soden’s.39 While large portions of IR180’s and RIR110’s positions were flattened, the garrisons were intact and their supporting artillery was ready to lay down close defensive fire, stopping enemy infantry from crossing no-man’s-land and also sealing off any breaches of the German lines.

In the event that any enemy infantry did break into the German positions, someone had circulated a pamphlet through the dugouts and gun pits of RIR110 outlining several phonetic translations of useful English-language phrases. The obviously English-speaking writer had a sense of humour:

Hands up you fool! (Honds opp ju fuhl!). . .

Hands up, come on Tommy! (Honds opp, kom on Tomy!)40

‘JUST BEFORE ZERO hour, I was sat on a fire step, three of us pressed close together,’ recalled Lance-Corporal Archibald Turner, 10th Lincolns, of a conversation about the shellfire in 34th Division’s sector.41 ‘Chap on one side said: “If there’s a bugger for you, you’ll get it.” Just then a shrapnel shell burst just above us and he got a shrapnel ball through his helmet and was killed outright.’ The third man’s leg hung by a sinew. ‘He asked me to cut it off but I only had a knife and I didn’t want to give him gangrene and, anyway, it was time to go over.’ Private William Senescall, 11th Suffolks, recalled German shellfire — ‘Wouf, Wouf, all around’ — and the throaty crackle of machine guns. ‘I now for some reason began to feel panicky. I just felt like bolting or something.’42 Private Michael Manley, 26th Northumberland Fusiliers, wanted the ordeal over. ‘You know it’s going to be rough. I was scared when the shells came over it didn’t half put the wind up you.’43 Private William Corbett, 15th Royal Scots, recalled ‘the expression of expectancy on the faces of these men standing side by side with thoughts of home and their loved ones whom most of them would never see again.’44

Walk around the duckboard track circling Lochnagar crater today and the military value of the German redoubt that once stood here is plain to see. From this place — Schwabenhöhe — you have a more than 180-degree panorama over 34th Division’s assembly trenches from Sausage Valley around to Avoca Valley, which runs between the Albert–Bapaume road and Bécourt Wood. Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Somerset, 11th Suffolks, said that, unless destroyed or suppressed, this redoubt would inflict heavy casualties as infantry crossed the grassland expanses of no-man’s-land.45 That was why III Corps opted to blow it sky high — the trenches, machine-gun posts and dugouts occupied by a company of RIR110 vaporised in one fell swoop — and send the infantry in once the debris had settled. Nobody knows how many the blast killed, but the number was not great, probably a couple of dozen.46 ‘When the English infantry began their mass attack with the huge explosion at the 5th Company [sector] . . . we immediately made ourselves ready to be deployed,’ said Vizefeldwebel Theodor Laasch, RIR110,47 whose platoon was in reserve dugouts just behind La Boisselle and would participate in the fighting against both 8th and 34th Divisions.

Thirty-fourth Division’s lead battalions were mostly swept down by machine-gun fire. They each moved forward on a frontage of 250–400 yards. To the north, the 102nd attacked either side of La Boisselle Spur, some battalions up Mash Valley and others between the village and Lochnagar crater. Further to the south, 101st Brigade attacked along Sausage Valley and along the northern slopes of Fricourt Spur. Each of these brigades had two battalions of the 103rd attached. Within 10 minutes 80% of the men in the leading battalions — from left to right, 20th,* 23rd† and 21st Northumberland Fusiliers,‡ 10th Lincolns§ and 15th Royal Scots,¶ all of which advanced in linear waves48 — were casualties. This was the result of ready-and-waiting German machinegunners and riflemen generally winning the race for their parapets and spraying no-man’s-land with tens of thousands of bullets.49 There were no fewer than 30 machine guns with interlocking fields of fire spread across RIR110’s sector.50 Follow-up battalions moved forward — 22nd Northumberland Fusiliers,** 11th Suffolks†† and 16th Royal Scots‡‡ in the second wave in extended order,51 with the 103rd’s 25th,* 26th,† 24th‡ and 27th Northumberland Fusiliers§ in the third and deployed in waves of columns of platoons.52 The result was multiple battalions concertinaed in no-man’s-land, confusion, failing command structures and appalling casualties.

In the 101st’s right column, 15th Royal Scots moved within 200 yards of the German line before the barrage lifted and, with a skirling of bagpipes, was over and beyond the flattened enemy parapet on the southern slopes of Sausage Valley, and soon atop Fricourt Spur. It was followed forward by 16th Royal Scots. Private Frank Scott, 16th Royal Scots, found the German trenches to be ‘absolutely battered to bits, practically just chalk heaps and hardly anybody in it. Those left were so demoralised that they hadn’t a fight left in them but surrendered right away.’53 A Royal Scots officer watched the attackers from the assembly trenches: ‘They move about deliberately, taking steady aim at the foe crowning the slope [of Fricourt Spur], and pushing upward slowly but surely. . . . The little clusters of men gradually fall into the [trench] line towards the top of the slope.’54 Both battalions suffered under machine-gun fire in Sausage Redoubt and La Boisselle, briefly veered into the neighbouring XV Corps’ sector and were pushed from their most advanced gains, which were around Birch Tree Wood and a trench running northeast towards Peake Wood.55 Scots Redoubt was taken. Sausage Redoubt remained defiant; flame throwers incinerated a small party trying to storm its defences. A few groups of the following battalion, 27th Northumberland Fusiliers, made it across no-man’s-land behind the Royal Scots. The 101st’s right column had done well to force an entry to the German line, but come noon its most advanced line was a 250-yard-long stretch of Wood Alley trench between Scots Redoubt and Round Wood atop Fricourt Spur.

Incredibly, some small groups of soldiers progressed much further, towards Contalmaison, roughly 2000 yards behind the German front line. A mixed bag of 15th and 16th Royal Scots and 27th Northumberland Fusiliers, along with some 10th Lincolns and 11th Suffolks, whose ordeal will soon be discussed, had fought determinedly to hold the trench between Birch Tree Wood and Peake Wood, which was on the approach to Contalmaison. They were forced to retire after desperate close-quarter fighting.56 Corporal George Lowery, 27th Northumberland Fusiliers, came face to face with a German officer in the enemy trenches: ‘He fired at me with his revolver and missed me. Just as he was going to fire a second time I threw the bomb, which blew his head off.’57 Private Tom Hunter, 16th Royal Scots, saw a friend killed as he peeped round a trench corner. ‘I threw my bomb round the corner and the lads followed up with the bayonet. It [the ensuing fight] did not last long.’58

One small band of 16th Royal Scots actually entered Contalmaison,59 the furthest advance achieved on 1 July. A few of the 27th Northumberland Fusiliers also reached the shellfire-damaged village, while several of the 24th Northumberland Fusiliers almost made it that far, too.60 Roughly 14 wounded soldiers from several of these units were captured and held in Contalmaison until they and the village were liberated several days later.61 One of these soldiers later described his experience:

There were eight or nine other Englishmen, all wounded, lying there; and I was in front, right in the mouth of the [German] dugout, where I could see the trench, where a lot o’ Boches was sitting, smoking cigarettes, an’ talking in their own lingo. By an’ by a German officer comes along. I knew he was coming by the way these chaps jumped an’ dropped their smokin’ and talkin’. They came to attention pretty smart; I’ll say that for ’em.62

The 101st’s left column, meantime, suffered heavily as it advanced along Sausage Valley. Tenth Lincolns and the following 11th Suffolks were swept down by machine-gunners in Sausage Redoubt and around La Boisselle; they were destroyed as effective units within 30 minutes.63 ‘In spite of the fact that wave after wave were mown down by machinegun fire, all pushed on,’ wrote 11th Suffolks’ war diarist.64 ‘We often saw entire platoons bunch together so long until one after the other was shot down,’ wrote one German observer.65 Precious few from the leftflank platoons made it to the Lochnagar crater and adjacent ground.66 Some 24th Northumberland Fusiliers, coming forward behind the 11th Suffolks, now went forward under ‘intense machine gun fire’ and, while a number did get across no-man’s-land, the battalion’s attack was otherwise halted.67 A few hundred soldiers from all three battalions had snatched a limited footing in and around the crater, but further up Sausage Valley the formidable Sausage Redoubt, which had wreaked so much havoc, remained resistant and deadly.

Oberleutant-der-Reserve Kienitz, a machine-gun officer in RIR110 near Sausage Redoubt described the attack:

The serried ranks of the enemy were only a few metres away from the trenches when they were sprayed with a hurricane of defensive fire. Some individuals stood exposed on the parapet and hurled hand grenades at the enemy who had taken cover to the front. Then, initially in small groups, but later in huge masses, the enemy began to pull back towards Bécourt [opposite the entrance to Sausage Valley] until finally it seemed as though every man in the entire field was attempting to flee back to his jumping off point. The fire of our infantrymen and machine guns pursued them, hitting them hard. . . . Our weapons fired away ceaselessly for two hours, then the battle died away.68

Lieutenant-Colonel Somerset’s grim forecast had proved correct. ‘The bombardment had by no means extinguished the German machine guns which increased their fire as the waves advanced, and our Artillery barrage moved off the front line of the German system,’ he wrote.69 ‘They were almost wiped out & very few reached the German front line.’ An artillery smoke screen on La Boisselle was largely unsuccessful, due to the direction and weakness of the wind, and failed to obscure German machine-gunners’ views.70 ‘The Germans put down a terrific barrage on our front line directly the assault commenced & opposite La Boisselle it was doubled. Chapes Spur & the forward slopes of Tara & Usna [Hills] were swept by machine gun fire,’71 Somerset said. ‘The 11th Suffolks in the support line had further to go & walked straight into the German barrage.’72 This was the ghastly experience of all of the 34th’s follow-up battalions, not just 11th Suffolks.

Attempts to cross no-man’s-land by the three sections of 207th Field Company, Royal Engineers (RE), at about 10 a.m. faltered in the face of ‘impossible’ machine-gun fire.73 At 1 p.m., a single company of 18th Northumberland Fusiliers (with about 30 bombers from 10th Lincolns) attempting to reinforce the Royal Scots also failed to get across.

Survivors recalled chattering machine guns and likened the patter of bullets to heavy rain or hail. They told of friends falling face down, one after another, and wondered when they themselves would be hit. ‘It shook my faith in every certainty. Your officers, your pals, maybe even men you didn’t care for much, all falling in front of you,’ wrote Lance-Sergeant Jerry Mowatt, 16th Royal Scots.74 Private Lew Shaugnessy, 27th Northumberland Fusiliers, was at first curious when he saw scores of soldiers falling around him: ‘I wanted to find out what they were looking for, it didn’t occur to me that they were men in their death agonies kicking and screaming.’75 Others spoke of near misses, shot-through tunics and equipment, fractured bones, arterial spurts, gunshot wounds to limb or torso and of bullets slamming into corpses. Some veterans even remembered the smell of battle: Private Corbett, 15th Royal Scots, said the stench of cordite ‘resulted in an atmosphere that was choking to the throat.’76 Those who advanced furthest often felt isolated and put their progress down to luck. The wounded spoke of terrible injuries and prolonged, parched agony.

Machine-gun fire almost tore Captain Peter Ross, 16th Royal Scots, in two at the waist. The mathematics teacher was in unimaginable pain and begged somebody to end his misery. It came down to an order; two of his men reluctantly obliged.77

No-man’s-land was covered with hundreds of soldiers, the living motionless and pressed hard to the ground to avoid snipers’ bullets. Private Senescall saw a man shot in the head. ‘I distinctly heard, in spite of the other noises, him give a loud groan.’78 He saw ‘Gerry hats moving about’ in trenches further up Sausage Valley. A shell landed nearby:

With all the bits and pieces flying up was a body. The legs had been blown off right up to his crutch. I have never seen a body lifted so high. It sailed up and towards me. I can still see the deadpan look on his face under the tin hat, which was still on, held by the chin strap. He still kept coming and landed with a bonk a few yards to my left. Lucky me that he missed me.79

More shells burst near Senescall, followed by a spatter of bullets. A delirious soldier sobbed for his mother: ‘He sounded like one of the fifteen or sixteen year olds of which there was a sprinkling in the battalions.’80 Dusk fell, and, after a testing 13 hours in no-man’s-land, Senescall bolted roughshod over bodies until he made it back to the British lines. Private Edward Dyke, 26th Northumberland Fusiliers, chanced his arm, too: ‘The return to safety was as bad as the charge. We came down a slope, which we had now to ascend. Machine guns were rattling, and German snipers from the opposite hill were picking off the wounded.’81

The mixed bag of 10th Lincolns, 11th Suffolks and 24th Northumberland Fusiliers who had reached the crater held its still-warm rim closest to the German trenches. Soon enough, machine-gun fire played along the chalkstone lip; the wounded and dead rolled down into its still-steaming core. ‘It was as hot as an oven after just being blown up,’ said Lieutenant Ambrose Dickinson, 10th Lincolns.82 Nearby, Lieutenant John Turnbull, same battalion, was wounded in the spine as he crawled for the crater: ‘There were 50–100 unwounded men. We consolidated around the lip of the crater; our parapet was of uncertain thickness and very crumbly. There was a certain amount of cover for all but very shallow,’ he later wrote.83 Turnbull continued: ‘I found my flow of language very useful several times; especially when the fit men wanted to bolt for it and leave a good hundred wounded who couldn’t walk. I asked them what the — — they thought they were doing and they all meekly went back, much to my surprise.’84 Private Frank Stubley, 10th Lincolns, made it beyond the crater but said machine-gun fire ‘cut us a bit thick just as we got over his second line. That is where he stopped most of us. He gave me one through my nose and out by the cheek.’85 These soldiers would hold the ground around and just beyond the crater rim for the rest of the day, incurring a constant trickle of casualties in the process.

A Russian Sap known as Kerriemuir Street extended almost up to the German front line near Lochnagar crater and was used as a forward supply route for bombs, ammunition and water.86 Two other Russian Saps on III Corps’ front were Waltney in 2nd Lincolns’ sector and Rivington in 2nd Royal Berkshires’ area; the former was opened on 1 July but apparently went unused, while the latter remained unopened. Meantime, Kerriemuir Street was 12–14 feet below ground, its 410-foot-long corridor being almost 9 feet high and roughly 3 feet wide.87 It finished about 180 feet short of the German line, a jot northwest of the crater, and had its head opened late on 30 June.88 From about 10 a.m., it was clogged with wounded men heading back and supply parties moving forward. By about 7 p.m. it had been extended to the old German front line.89 It was via this route that 18th Northumberland Fusiliers and 209th Field Company, RE, lugged forward bombs, ammunition, water and so forth. ‘It was due to their exertions that the men in the front line were able to hold on,’ wrote 34th Division’s war diarist.90 As one soldier who plied this course later wrote: ‘A small [Russian] Sap head had been blown [open] not many yards from the German front line and through this came supplies and we also got a telephone cable from it and we signals [sic] fixed up a telephone to Advanced Brigade H.Q. & this was fixed up at the bottom of some stairs of a German front line dugout.’91

Through the afternoon German officers and NCOs set to reorganising RIR110’s garrison, particularly in the areas where 101st Brigade had broken into its lines. That meant organising counterattack groups, establishing which ground was still German-held and, most importantly, working out exactly where the enemy was. Unteroffizier Gustav Brachat, RIR110, tried to make contact with parties of German soldiers near Scots Redoubt. ‘I suddenly heard “Halt”. I stood in front of a barricade and firmly determined through listening and observing that it was occupied by Englishmen. I went back to relate the news to my platoon.’92

CLOSER TO THE Albert–Bapaume road the 102nd made limited, bloody headway. In the right column, 21st Northumberland Fusiliers began crossing the 200-yards-wide no-man’s-land about two minutes before Zero and quickly overran the pulverised trenches between La Boisselle and the Lochnagar crater. It linked up with the 101st to its right at Schwabenhöhe. The 21st was followed by 22nd and then 26th Northumberland Fusiliers, which both suffered severely on the exposed eastern slopes of Tara Hill at the hands of the La Boisselle machine-gunners and the German defensive barrage.93 The fusiliers’ few survivors made it some 500 yards beyond the German front line, running into increasingly stiff resistance from support companies of RIR110 and Infantry Regiment 23 (IR23). Leutnant Paul Fiedel, IR23, likened the experience for his men to rifle-range shooting: ‘They grinned at their Leutnants with pipes in their mouths and were happy. This was an opportunity to do something other than the endless entrenching. A machine-gun crew of the 2nd Company, RIR110, smoked at their guns.’94

Whistles blew and Private Thomas Easton’s platoon of 21st Northumberland Fusiliers began moving towards the Lochnagar crater area. He was in one of the battalion’s later waves and noticed German machine-gun fire passing overhead: ‘This was so until we passed our own front line and started to cross no-man’s-land, then trench machine guns began the slaughter. Men fell on every side, screaming with the severity of there [sic] wounds, those who were unwounded dare not attend to them.’95 Dead lay on the enemy’s wire, and ‘their bodies formed a bridge for others to pass over and into the German front line.’ Small groups of bombers worked their way up communication trenches between La Boisselle and the crater. Grenades were tossed into dugouts and nests of resistance were bombed into submission:

There was [sic] fewer still of us but we consolidated the lines we had taken by preparing firing positions on the rear of the trenches gained, and fighting went ok all morning and gradually died down, as men & munitions on both sides became exhausted. Some of our Battalion troop got consolidated on the edge of the Great Crater on our right, but little further progress was made.96

The severely wounded lay in a 30-foot-deep dugout in the old German front line, but ‘many of them just died, for nothing much could be done until darkness set in.’ Easton recalled sitting briefly with an older soldier named Jack in the captured trench. Jack was delirious; he reckoned he could hear a band playing. ‘This man finally flopped forward and he had no back. He had been hit by an explosive bullet which blew out the whole of his back between the shoulders and he was dead.’ Easton continued, ‘the day wore on, no rest, no let up, wounded men pleaded for water to make up the blood they had lost, but water was at a premium for the day had been hot.’ Company Quartermaster Sergeant Gawen Wild, 26th Northumberland Fusiliers, was wounded and hauled into a shell hole by a friend who was killed in the act. ‘You can imagine my feelings, lying there with one of my best chums who’d given his life to save mine,’ he wrote.97

Surprisingly, a few fusiliers made it to Bailiff Wood, near Contalmaison, about 2000 yards behind the German front line. As Leutnant-der-Landwehr Alfred Frick, Reserve Field Artillery Regiment 28 (RFAR28), told it: ‘Runners, telephonists and men from the Construction Company were formed into a defence platoon and set off under the command of Leutnant Strüvy [of Reserve Field Artillery Regiment 29 (RFAR29)]. This little united force succeeded in ejecting the bold intruders.’98 These endeavours towards Contalmaison, along with those mentioned earlier, were exceptions to the rule. The overall pattern was scores of Northumberland Fusiliers being shot down as they closed on the trenches held by IR23 a couple of hundred yards beyond the crater. Local counterattacks and limited bomb supplies saw the 102nd’s early gains halved within hours, and of the roughly 2100 officers and men of the 21st, 22nd and 26th Northumberland Fusiliers who set out, only several hundred remained in the German lines.

‘In the event of my death I leave all of my property and effects to My Wife Mrs Norah Nugent,’99 wrote Private George Nugent, 22nd Northumberland Fusiliers, before battle. He was killed within an ace of Lochnagar crater, likely by a bullet or shrapnel. The 28-year-old labourer’s bones were found there in 1998 and identified by an engraved cutthroat razor. A weathered oak cross with metal plaque now stands near the spot. Nugent — then a married father of a one-year-old girl — is now buried at Ovillers Military Cemetery. His epitaph’s opening line: ‘Lost. Found.’100 Captain William Herries, same battalion, made it further than Nugent but found his progress blocked by the support companies of IR23 and RIR110:

Most of the men were killed, and the only thing to do was to get a machine gun up, which we were fortunate enough to do. Then we gave them it hot. Further along [Captain John] Forster, [Lieutenant William] McIntosh and [Lieutenant Walter] Lamb got over with a party of men, but the whole lot were mown down with a machine gun. In the meantime our bombers were at work and reached their [German] third line, which they held for a short time, but out of which we were bombed step by step — all our bombs having been used. I won’t tell you of any of the scenes in the trenches, but I had to pull myself together with a mouthful of brandy once or twice. We were now busy digging the Bosches out of their dugouts. They all threw up their hands and yelled, ‘Mercy Kamerade!’ and seemed very surprised that they were not killed off.101

Forster and Lamb have no known grave and are today named on the Thiepval Memorial. McIntosh died of wounds on 6 July 1916 and is buried at St Sever Cemetery, Rouen.

Back in the British lines, battery commander Captain Ivan Pery-Knox-Gore, 152nd Brigade, Royal Field Artillery (RFA), saw a machine gun firing from La Boisselle’s southern outskirts, and resolved to break orders. ‘Took the law into my own hands, stopped firing per [barrage] time table and turned our gun onto the M.G. [machine gun]’102 His gun silenced that machine gun and several others nearby, and blew a sniper ‘to bits.’103 Pery-Knox-Gore then directed his guns to support the infantry’s limited gains just south of La Boisselle. ‘Turned our guns onto the points where M.G. & rifle fire were coming from & eventually silenced all & our men were left in peace & started consolidating. It was nervous work strafing the [German] bombers as at times they were only about 50 yards from ours.’104 Nervous work, too, for the infantry, as Lieutenant Turnbull recalled: ‘For some unknown reason, our artillery started shelling us with whizz-bangs.’105 He lit a red flare, signalling to an artillery-spotting aircraft, which flew off and alerted the batteries. The barrage was stopped. ‘Of course,’ wrote Turnbull, ‘the Boche redoubled his efforts, though we escaped without further casualties.’ Generally, though, the RFC’s contact patrols were a complete failure in III Corps’ sector, wrote Lewis of 3rd Squadron: ‘No flares or any ground signals seen. Nothing whatever to report to corps.’106

In Mash Valley the 102nd’s leading 20th and 23rd Northumberland Fusiliers were almost annihilated by machine-gun crossfire from Ovillers and La Boisselle.107 Here the width of no-man’s-land varied greatly, at the extremes 100–800 yards wide but mostly 500–750 yards. Fantastic as the Y-Sap mine blast appeared, it — along with two smaller ones at the Glory Hole — utterly failed to shatter resistance close to La Boisselle, or even provide piles of spoil high enough to reduce observation and enfilade from its ruins. Barely any of the 23rd reached the crater after starting off at 7.35 a.m. to avoid falling debris from the explosion. But some, along with disorganised groups of the neighbouring 20th, which began at 7.30 a.m. and had the widest stretch of open ground to cross, breached the German trenches north of La Boisselle. Fewer made it a hundred or so yards behind its piles: ‘It was seen later from the position of the dead that some [of the 20th and 23rd] had crossed the [German] front trench and moved on to the second before they were shot down, and that flanking parties had tried in vain to force an entrance to La Boisselle.’108

One officer amazingly walked unseen up the Albert–Bapaume road, into La Boisselle, collected some souvenirs from a German dugout and returned them to the headquarters of 102nd Brigade, which was commanded by Brigadier-General Trevor Ternan.109 Further back, Lieutenant James Hately recalled how the 25th Northumberland Fusiliers, coming on behind the 23rd, formed up in the western lee of Usna Hill, swapping ‘cheer’o’s and ‘good luck’s before moving up the slope:110 ‘I could see the men stumble and fall headlong or see others go up in the air, but still the remainder went steadily forward, till I lost them when they crested the hill.’111 Once over the crest, the exposed 25th, like the 103rd’s three other battalions, was briskly destroyed by the overworked Ovillers and La Boisselle machine-gunners: ‘Heavy fire from machine guns and rifles was opened on [the] battalion from the moment the assembly trenches were left also a considerable artillery barrage. . . . The forward movement was maintained until only a few scattered soldiers were left standing,’ wrote 25th Northumberland Fusiliers’ war diarist in his matter-of-fact after-battle report.112

A horrified Vizefeldwebel Laasch saw clusters of British soldiers behind his trench at the northeast end of La Boisselle, most likely some of the very few 20th or 23rd Northumberland Fusiliers who made it that far:

We fired, partly standing upright, into the Englishmen at close range. Did the excitement race through my veins or was our success still not damning enough for me? I staggered around between the groups and shouted: ‘Blast it, fire at them, fire at them!’ until an annoyed Landwehrmann yelled at me while loading: ‘By thunder Herr Feldwebel, I am firing!’ I fired there with him and it grew quieter. How we knocked them over like hares!113

Laasch ventured gingerly down a communication trench towards the front line. Suddenly he was confronted by three British soldiers: ‘I threw my hand grenade in front of their feet and jumped back as fast as lightning.’ Later he found the grenade had killed a British officer with red hair and freckles.

Thirty-fourth Division’s attack was effectively over by 10 a.m., although localised fighting would continue for the rest of the day. The division’s only meaningful gains were atop Fricourt Spur, around Scots Redoubt and Round Wood, where it was in contact with XV Corps, and a besieged footing around and slightly beyond Lochnagar crater. None of the 34th’s battalions came close to achieving even their first objectives, even though a few isolated groups advanced good distances beyond the German front line. ‘It was no fault of theirs that they did not reach their allotted objective,’ said Brigadier-General Robert Gore, commander of the 101st.114 The advances directly along Mash and Sausage Valleys were predictable failures. The wounded and unscathed alike sheltered in noman’s-land among the dead, under the blazing sun. Their chance to slip back unseen to the British front line — itself jammed with bloodied, broken men — would only come in the half light of dusk or under the cover of night. Until then they risked adding to what was an already swollen casualty roll: ‘Exposure of the head meant certain death. None of our men were visible but in all directions came pitiful groans and cries of pain,’ said one officer stranded in the Mash Valley no-man’s-land.115

Major-General Edward Ingouville-Williams, commander of the 34th, had gone forward to watch the attack begin. Most likely he saw the 103rd deploy and move over the Tara–Usna ridge where it was ‘met by machine gun and rifle fire.’116 ‘Inky Bill,’ as Ingouville-Williams was known, returned to his headquarters at 8.30 a.m. Thereafter the 34th’s battle log is studded with increasingly disturbing reports of heavy losses and an impassable no-man’s-land: carrying parties could not lug supplies forward to the most advanced infantry.117 ‘I reported, very bluntly I’m afraid, to General [Ingouville-]Williams that no objectives had been gained and the left wing (102nd Brigade) had suffered heavily,’ said Captain David James, 34th Trench Mortar Battery.118 Ingouville-Williams had no reserves, and telegraphed Pulteney late in the morning asking for 19th (Western) Division to help clear the area south of La Boisselle and allow the attack to proceed.119 Ninth Welsh was placed at his disposal, but it was insufficient for the job and not employed.120

The 34th’s bill: 6380 casualties, including 2480 dead, 3587 wounded and 313 prisoners or missing. Of the attacking battalions of 101st and 102nd Brigades, not one suffered fewer than 472 casualties. The undeniable conclusion is that the 34th had practically ceased to exist as an effective fighting formation by 8.30 a.m., probably much earlier. The Tynesiderecruited 102nd and 103rd were hit particularly hard. Their 20th, 23rd and 24th Northumberland Fusiliers losing 661, 640 and 630 officers and men respectively. Losses in the 103rd were particularly disturbing as its four battalions were shredded by bullet and shell on the exposed slopes of Tara and Usna Hills, well behind the British front-line trenches from which the attack began. Seven battalion commanders were casualties, five of them dead and two wounded.121 Brigadier-General Neville Cameron, commander of 103rd Brigade, was shot in the stomach at about 7.50 a.m. and hauled back to safety. ‘He smiled in that nice way of his, told me to carry on, he’d be alright,’ said Captain James. Cameron lived.

Casualty figures for the German units directly opposite the 34th cannot yet be determined with precision. For the period 23 June–3 July, RIR110 recorded 1089 casualties, including 193 dead, 397 wounded and 499 missing.122 Among these were a total of 195 fatalities for the periods 23–30 June and 2–3 July.123 The regiment’s casualty list for 1 July must therefore be no more than 894, and is almost certainly lower if non-fatal casualties on those other days are considered.124 This figure includes 235 soldiers who are confirmed 1 July deaths, the 659 others who were wounded, declared missing or taken prisoner.125 IR23 recorded just nine fatalities among its two companies attached to RIR110.126 Casualties in Landwehr Brigade Replacement Battalion 55, which was grouped around Contalmaison, were few, but precise figures are unavailable. Altogether the 28th suffered about 903 casualties against 34th Division’s 6380, this conservative ratio equating to at least one German casualty for every 7.1 British and emphasising the lopsided nature of the battle.

As far as 28th Reserve Division commander Hahn was concerned, the initial fighting around Mash and Sausage Valleys and La Boisselle went rather more than less to plan. First news of the British attack had reached his headquarters at about 8 a.m.127 Hahn’s artillery in this part of the battlefield had survived the bombardment in sufficient numbers to lay down defensive fire in support of the infantry positions to block enemy reinforcements coming forward.128 Overall, north of Fricourt Spur, the enemy had essentially been brought to a standstill from the outset, with heavy casualties inflicted. Any incursions were limited — such as astride the Lochnagar mine crater, or beyond Scots Redoubt and briefly towards Contalmaison. Company and battalion commanders were already organising the fightback with long-standing and well-rehearsed counterattack tactics. Wagon-loads of ammunition were already being brought forward to resupply the infantry.129 Available evidence suggests Hahn left his subordinate commanders to get on with the job, and that was because his focus and worries were already much further south, between Fricourt Spur and Mametz where the British XV and XIII Corps had made significant and critical inroads against his divisional sector.130

‘I COULD SEE nothing of what was going on in front. . . . Time and again we were covered with soil and debris thrown up by the [German] shells,’ wrote Major Jack, 2nd Scottish Rifles, of the assembly trenches before Ovillers where 8th Division was about to begin its attack:131

The strain on the waiting men was very great, so I took to joking about the dirt scattered over my well-cut uniform, while dusting it off with a handkerchief. We knew at 7.30 that the assault had started through hearing the murderous rattle of German machine guns, served without a break, notwithstanding our intense bombardment which had been expected to silence them.

Lieutenant Alfred Bundy, 2nd Middlesex, said the moments before Zero were an ‘interminable period of terrible apprehension.’132 Captain Alan Hanbury-Sparrow, 2nd Royal Berkshires, remembered the smoke of shellfire and that a ‘reddish dust was over everything. There was a mist, too, and hardly anything was visible.’133

North of the Albert–Bapaume road, 8th Division committed all three of its brigades to the attack across the camber of Ovillers Spur, with its left and right flanks dipping into Nab and Mash Valleys respectively. It would come up against machine-gun fire from Leipzig, Nordwerk and Mouquet Farm Redoubts to the north, Ovillers centrally and La Boisselle to the south. Leipzig Redoubt and La Boisselle were outside the 8th’s sector. For these reasons it seemed to the divisional commander, Major-General Havelock Hudson — who was ‘quick enough to see what was going to go wrong’ but lacked the personality to challenge his superiors134 — that the 8th had little chance of success unless neighbouring divisions advanced a little ahead of his own.135 Hudson’s request to postpone the 8th’s Zero hour was rejected by Fourth Army,136 which meant his division was condemned to Pulteney’s generally guileless attack scheme.

All three of the 8th’s brigades would cross a steadily rising no-man’sland that was 200–800 yards wide, but mostly 200–400 yards. In theory their objectives, including Ovillers, ran 2500–3500 yards behind the German line before finishing around Pozières on the main ridgeline. In reality, the survivors of the 8th’s heavily casualty-depleted battalions who made it across no-man’s-land were ejected within hours. Some lingered until mid-afternoon. By day’s end all that remained of the 8th’s limited gains were numerous bloody khaki bundles scattered between the scarlet poppies and grass of no-man’s-land, and in and around the German trenches.

Eighth Division’s leading battalions crept closer to the German trenches a few minutes before Zero, while the last of the intensive shellfire rained down. Their attack was to start at 7.30 a.m., each battalion on a frontage of 250–400 yards. Machine-gun fire from Ovillers, the German first and second trenches, and in enfilade from La Boisselle tore into the infantry on the bare no-man’s-land. Survivors pressed forward. Within 80 yards of the German parapet the machine-gun and rifle fire rose to a crescendo, while 26th Reserve Division’s intact field guns threw down a curtain of shellfire on no-man’s-land and also on the British front and support lines. Casualties were predictably heavy. Survivors charged forward and soon the ‘excellent’ waves were gone, jumbled together in chaos: ‘Companies became mixed together, making a mass of men, among which the German fire played havoc.’137 Only isolated parties reached the German lines, and never in sufficient strength to alter the one-way course of battle.

‘The attack on our part of the line was immediately recognised by the lifting back of the enemy’s artillery fire,’ said Oberstleutnant Alfred Vischer, commander of IR180.138 ‘Everyone rushed out of their deep dugouts and occupied the crater ground and trenches, if they were still recognisable and usable. Machine guns were in position and red flares demanded our artillery barrage. A raging infantry, machine gun and artillery fire brought the attack to a halt.’ IR180 had about 24 machine guns across its sector sited to co-operate with one another and provide direct fire and enfilade in support of the front-line infantry.139 Captain Hanbury-Sparrow watched the leading companies of 2nd Royal Berkshires fade into the mist, and ‘as they did so, so did the first shots ring out from the other side.’140 Later, as the mist cleared, he saw ‘heaps of dead, with Germans almost standing up in their trenches, well over the top — firing and sniping at those who had taken refuge in shell holes.’

The attacks of 23rd and 25th Brigades produced depressingly similar outcomes. On the Mash Valley slopes of Ovillers Spur, few of the 23rd’s 2nd Middlesex* and 2nd Devons,† which both advanced in linear-wave formations and began deploying at 7.23 a.m.,141 beat the crossfire odds after clearing the parapet and creeping through lanes cut in the wire: ‘The enemy opened with a terrific machine gun fire from the front and both flanks which mowed down our troops,’ wrote 2nd Devons’ war diarist in an entry that applied equally to 2nd Middlesex.142 Some miraculously made it to the German line just south of Ovillers, fewer of them a couple of hundred yards beyond, before being pushed back, killed or captured.143 A bit to the north, as Ovillers Spur fades into Nab Valley, the 25th’s 2nd Royal Berkshires,‡ advancing in a mix of linear waves and columns of sections from 7.30 a.m., and 2nd Lincolns,* which began deploying at 7.25 a.m. and likely used a similar attack structure,144 met a storm of machine-gun fire from the front and in enfilade.145 ‘The machine guns were in good condition and did deadly trade,’ wrote Oberleutnant-der-Reserve Vogler in a succinct after-battle summary.146

Directly in front of Ovillers, 2nd Devons’ left companies and those on 2nd Royal Berkshires’ right were gunned down. Stand on the old German front line here, atop the spur behind Ovillers Military Cemetery, and you can still find scores of 1916 Spandau bullet casings oxidised to green. ‘The enemy had exceptionally high losses,’ said Oberstleutnant Vischer.147

A jot further north some 2nd Lincolns worked their way into the wrecked German trenches at about 7.50 a.m. by short rushes from one shell crater to the next.148 In places they progressed a little further, but these men were soon forced back. Follow-up battalions — the 23rd’s 2nd West Yorkshires,† likely in linear waves, and the 25th’s 1st Royal Irish Rifles‡ in columns of platoons149 — suffered in the German defensive shellfire, and then in the machine-gun fire sweeping no-man’s-land. Just 10 men of 1st Royal Irish Rifles managed to cross.150 The 2nd West Yorkshires later estimated it suffered 250 casualties behind the British front line: just shy of half its casualties for the day.151 One of that battalion’s companies lost 146 of the 169 men who went into action behind 2nd Middlesex.152 Shortly after 9 a.m. both brigades’ toeholds in the German lines collapsed under concentric bomb and bayonet counterattacks. With heavy casualties, limited ammunition and essentially no prospects of being reinforced, it was only a matter of time before those few men in the German trenches were forced back into no-man’s-land to skulk in crowded shell holes.

‘I struggled on and seemed to be quite alone, when I was bowled over and smothered by debris from the mine,’ remembered Private Frank Lobel, 2nd Middlesex,153 more likely referring to a large shell burst as he was too far away to be hit by mine debris. ‘I tried to find some comrades, but could not do so. . . . To this day I can only think of it [1 July] in sorrow.’ Lieutenant Bundy wrote of the din, acrid fumes and smoke and dust that limited visibility: ‘Suddenly an appalling rifle and machine-gun fire opened against us and my men commenced to fall. I shouted “Down!” but most of those who were still not hit had already taken what cover they could.’154 After a series of dashes, Bundy was back within an ace of the British parapet. He watched helplessly as ‘sparks flew from the wire continuously as it was struck by bullets.’155 Eventually the fusillade abated and he scrambled into the trench. Major Henry Savile, 2nd Middlesex, said mutually supporting enfilade from Ovillers and La Boisselle caused most of the Mash Valley casualties: ‘Any sign of movement in No Man’s Land was immediately met with a burst of fire.’156 Those who made it across were reorganised in some 300 yards of the German front line, and this was ‘held for two hours until their numbers very greatly reduced they were driven out by German counter attacks from both flanks.’157 Meantime, Major Jack readied his company of 2nd Scottish Rifles* to reinforce Savile’s men in the German line: ‘I stepped back several paces to take a running jump on the parapet, sound my hunting horn and wave my waiting men on.’ Just then a message cancelling the attack arrived: ‘What a relief to be rid of such a grim responsibility.’158

Vizefeldwebel Laasch, who was commissioned after the Somme, was one of the La Boisselle machine-gunners firing at the 2nd Devons and 2nd Middlesex in Mash Valley, among them Lobel, Bundy and Savile: ‘Tightly packed lines poured out of the English trenches, strode across the wide foreground [of Mash Valley] and ended up in the heavy defensive fire of Regiment 180. I also fired one belt after another into the flank of the ever-advancing English battalions with our machine gun. Never in the war have I experienced a more devastating effect of our fire: the fallen were tightly packed in the entire hollow up to Ovillers!’159

Twenty-fifth Brigade’s break-in just north of Ovillers lasted only a couple of hours. Private Fred Perry, 2nd Lincolns, said ‘few of us got to the German front line and all our team got wounded. We made our way back as well as we could, when we arrived in our trenches we had to walk over dead soldiers.’160 About 70 of Perry’s battalion made it to the German trenches, where Reservist Gottlob Trost, IR180, saw a friend locked in a vicious punch-up with a soldier of 2nd Lincolns: ‘The 180th man finally incapacitated his opponent with a stiletto knife he carried with him in the shaft of his boot. The fight was over. The Englishman was seriously wounded.’161 Trost does not state whether the wounded soldier died or was taken into captivity. Among the other 2nd Lincolns in the German line was Lieutenant-Colonel Reginald Bastard: ‘We drove off a counter attack from the German 2nd line Trench, but were bombed out when we had exhausted our own bombs and all the German ones we could find, we only retired to the shell holes in no man’s land.’162 Further attempts would have been a ‘useless sacrifice of life,’ and in any case brigade headquarters had already ruled against it. Bastard later made it back to the British lines and reorganised the 100-man garrison for defence: ‘Captain [Robert] Leslie and myself were the only two not hit of the officers, I had 3 bullet holes through my clothes and Leslie 2.’163

In Nab Valley, 70th Brigade’s attack in successive linear waves was a bloody disaster that included yet another short-lived breach of the German line.164 Thirty-second Division’s quick gains at Leipzig Redoubt, about 1000 yards northwest, briefly occupied the attention of machinegunners in Nordwerk Redoubt. It was all that remnants of 8th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry’s (KOYLI)* and 8th York & Lancasters’† leading waves needed to cross the levelled German front line, having deployed at 7.27 a.m. and started their attack at 7.30 a.m.165 Some elements of these battalions reached the German front-line system’s second trench and beyond. Schütze Fischer had hauled his machine gun up to the parapet to meet 8th KOYLI’s attack head-on: ‘At a distance of only 40–50 metres [44–55 yards] I could see figures in English uniforms with sparkling bayonets.’166 His weapon dealt ‘death and destruction’ to the incoming waves of men, but small parties broke in to the left and right of his position and closed in with rifle fire and grenades: ‘After a short bayonet fight we retreated back into our dugout. . . . The English fired a few shots into the dugout but didn’t have the guts to come down. They called then something like “Gom on,” which probably meant “Come up!” We did not react to it.’167

It was somewhere near here that Gefreiter Karl Walz, IR180, was killed. The 25-year-old Swiss, who had volunteered to fight in the German army, wrote home not long before the battle that he had tired of trench life, but had some good news: ‘We have been fitted out with new uniforms, which was really necessary. Now we look very smart again.’168 He has no known grave.

Seventieth Brigade’s always limited progress into the German lines petered out due to heavy casualties and loss of momentum in the face of increasing resistance. Support battalions were mauled by the German shellfire and machine guns, few getting across no-man’s-land and through the partially cut wire. Eighth KOYLI estimated 60% of the men in its two follow-up waves became casualties before reaching the German wire.169 Much the same bloody fate was meted out to 9th York & Lancasters* and 11th Sherwood Foresters,† which followed at 8.40 a.m. and about 8.56 a.m respectively.170 Ninth York & Lancasters lost more than half its strength either in its assembly trenches or between there and the British front line. The battalion suffered further casualties when it actually began its attack. The killing-zone ordeal of 11th Sherwood Foresters was noted by brigade headquarters: ‘It was impossible to stand at all in No Man’s Land and the Battalion crawled forward on hands and knees to the help of the Battalions in front.’171 Few got there.

Corporal Don Murray, 8th KOYLI, recalled his passage across noman’s-land: ‘It seemed to me, eventually, I was the only man left. I couldn’t see anybody at all. All I could see were men lying dead, men screaming, men on the barbed wire with their bowels hanging down, shrieking, and I thought, “What can I do?” I was alone in a hell of fire and smoke and stink.’172 Sergeant William Cole, 11th Sherwood Foresters, made it about 50 yards into no-man’s-land: ‘I had a shock like a thousand volts of electricity going through my shoulder and out at the top of my right arm, and I knew I was finished for a bit, but not done.’173

By now the Nordwerk machine-gunners had returned their focus to Nab Valley. Their fire sweeping over the northern slope of Ovillers Spur and the valley bottom was so intense that all communication between the British assembly trenches and 70th Brigade’s soldiers in the German lines was lost. Oberstleutnant Vischer saw 150–200 British soldiers ‘mowed down’ on the Nab Valley–Thiepval road. In no time the 70th’s footing was besieged by machine-gun and rifle fire, while hastily organised German bombing parties forced its men back with co-ordinated counterattacks closing from multiple directions. It was here, in Nab Valley, that Vizefeldwebel Albert Hauff, IR180, led one such group of bombers forward, as one of his men later recalled:

Now it was time to drive the enemy out. We went in over piles of corpses and used hand grenades to clean up the position. Those Englishmen who weren’t dead or wounded crept back into the shell holes [of no-man’s-land]. Any sign of resistance from them was showered with grenades. . . . Immediately we began to dig out collapsed shelters and make the trench defensible again. Some reinforcements came forward.174

Hauff was decorated for his bravery, but was killed in September 1916. Meanwhile, by 3 p.m. the 70th’s survivors had pulled back into the Nab Valley no-man’s-land. ‘I brought my machine gun back into position and shot at the fleeing English,’ wrote Schütze Fischer.175

‘Well, Martin, we will have lunch in the German trenches,’ said Lieutenant Billy Goodwin, 8th York & Lancasters.176 The 23-year-old, Tralee-born Corpus Christi College graduate was liked by subordinates because he ‘always looked after them before he looked after himself,’ said Private Patrick Martin, same battalion. Before the war Goodwin had enjoyed golf, tennis, rugby and racing around leafy country lanes on his motorcycle. But in Nab Valley on the warm morning of 1 July those days came to an abrupt end, as Corporal George Booth, 8th York & Lancasters, explained: ‘He advanced towards the German lines — was shot and fell on the barbed wire (German). . . . He seemed quite fearless in the attack. I went over the top at the same time, was slightly wounded and lay in the open for about 12 hours. Lt. Goodwin was still on the wire when I got away.’177 Goodwin’s body was found and he is today buried at Blighty Valley Cemetery, Authuille Wood, where 227 of the 491 identified burials are for 1 July. Schütze Fischer remembered another horribly wounded British soldier snared in the entanglement: ‘He shot at me a few times but the bullets just missed my head.’178 Fischer does not state this soldier’s fate, but he was likely shot.

Attempts to renew 8th Division’s attack amounted to nothing. Shortly after 9 a.m., Brigadier-Generals Harry Tuson of the 23rd and John Pollard of the 25th asked divisional headquarters to bring the barrage back to the German reserve trench line and Ovillers as a defensive measure:179 ‘It could not well be turned on to the front system, which the Germans had manned again at most places, as our men were lying close up to it, even where they were not thought to be in it.’180 Divisional commander Hudson sanctioned a half-hour shoot, and told Tuson and Pollard to organise a fresh attack. They and the 70th’s Brigadier-General Herbert Gordon said they had too few men — his portion of the British front line was held by fewer than 100 men as well as the 15th Field Company, RE — given that the German trenches were now fully manned, also noting a fresh bombardment would likely hit British infantry sheltering nearby in no-man’s-land.181 This was relayed to III Corps’ Montigny headquarters at 12.15 p.m.182 Pulteney, aware the 23rd and 25th were ‘hung up’, but believing more favourably that the 70th was ‘holding’ the German front line,183 decided to rejuvenate the attack north of Ovillers at 5 p.m., prefaced with 30 minutes’ shellfire. The 70th would continue its advance in conjunction with 19th (Western) Division’s 56th Brigade closer to Ovillers.184 The decisive factor in Pulteney’s thinking was the 70th’s presence in the German lines that afternoon, which led him to believe that regrouping and applying fresh troops would produce results.

It is not clear whether Hudson challenged Pulteney’s decision on the basis of his brigadiers’ refusal, but it seems improbable. Hudson lacked the ‘personality to be insubordinate & refuse’ pressure from higher office.185 Events rendered the matter moot: the 70th’s eviction forced Pulteney to cancel the planned attack. The field companies of 1st and 2nd Home Counties (Territorial Force), RE, were sent up to help hold the British front line, and were later put to work bringing in wounded. ‘Wiser counsels,’ wrote the official historian somewhat cryptically of Pulteney’s fruitless attempts to renew the attack, had ‘prevailed.’186

Eighth Division ran up 5121 casualties, including 1927 dead, 3095 wounded, 86 missing and 13 prisoners.187 ‘The experience of this day had been bitter, and its losses terrible,’ wrote the division’s historians.188 Ten of its 12 infantry battalions lost more than 374 men each, with the six that led the attack off suffering an average of 505 men killed, wounded and missing.189 Schütze Fischer, the machine-gunner, later said British dead lay thick in no-man’s-land outside Authuille Wood: ‘Not only were they laying [sic] side by side but also one on top of the other.’190 Several battalions lost all their officers, while seven battalion commanders became casualties — two of them killed, two died of wounds and three more wounded.191 Second Middlesex was worst hit, with 623 (92.6%) of the 673 officers and men who went into battle becoming casualties. Only 50 turned up at roll call the next day. Its commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Edwin Sandys, was wounded and evacuated to England. Two months later the 40-year-old shot himself dead: ‘I have come to London today to take my life. I have never had a moment’s peace since July 1.’192

IR180’s casualties totalled 280, or about 10% of its nominal strength, including 83 dead, 184 wounded and 13 missing.193 For every one German casualty there were about 18 British, this ratio reflecting IR180’s total dominance across its battle sector: ‘The losses of the enemy were atrociously heavy. Fifteen hundred to 2000 corpses were mown down in entire rows lying there in the evening in front of the sector of the Württemberg regiment. On the other hand, the losses of the regiment were fortunately small,’ wrote one German historian.194

‘I drove like the wind,’ wrote Fahrer Otto Maute, IR180, of his evening journey towards the front line with an ammunition-laden wagon and under shellfire.195 He was on the Albert–Bapaume road and showered by shrapnel fragments the ‘size of your fist.’ Maute pondered the consequences of being wounded: ‘What would it be like to receive a direct hit from a ship’s thirty-centimetre gun?’ He dumped the ammunition in a forward collection zone and raced back to Warlencourt, where the walking wounded were already filtering back with predictably alarmist stories: ‘Our regiment had heavy losses in the attack, but [on Thiepval Spur, the neighbouring] Regt. 99 [RIR99] came off worse, they say fifty per cent.’ He wrote to his family of the devastation: burning and smashed villages, and aircraft shot out of the sky. ‘At home you simply have no idea of what war is like.’

From Soden’s viewpoint, the fighting between Leipzig Redoubt and Ovillers paled in comparison with the danger caused by 36th (Ulster) Division’s break-in above Thiepval. His attention rightly lay on that latter part of the battlefield, which was the most tactically important feature within the 26th’s entire defensive scheme. Soden’s thinking was based on battle reports that showed IR180 had quickly gained control of its sector, with any break-ins either already ejected or in the process of being evicted. The few short-lived enemy incursions into IR180’s territory were never going to unravel Soden’s southern-most regimental position, let alone test Pozières Ridge further back. Soden knew his Nab Valley–Ovillers defence-in-depth scheme had been battered by shellfire, but crucially that mutually supporting redoubts, strongpoints and trench systems remained functional and defensible. Most of IR180’s infantry and machine-gunners had survived the bombardment and responded quickly to the lifting of the British barrage. Moreover, 26th’s artillery provided effective defensive fire as required. ‘The enemy’s plan of attack was thwarted,’ wrote Soden in a crisp summary of the fighting around Ovillers, also noting the artillery’s ‘outstanding achievements’ in helping secure the victory.196

SUCH INSIGHTS WERE lost on Pulteney who, in the 1930s, coughed up a facile explanation. ‘The main thing overlooked was the fact of the trenches being obliterated giving no cover for the attackers when reached, no one realised the depth of the German “Dug Outs”, our own Dug outs were miserable attempts, the ground was absolutely strewn with our own 8-inch dud shells.’197 Fair enough, there were too many dud shells. But it was risible to state that ‘the main thing’ behind III Corps’ failure was obliterated German trenches, as well as the unrealised depth of the German dugouts. Pulteney’s corps had known of the deep dugouts since early June. And what had he expected from the seven-day bombardment — scores of dead German soldiers and pristine trenches awaiting new tenants? He was also well aware of the functional German defence-in-depth scheme, the failure of his counter-battery fire, faulty intelligence and the numerous unsuppressed machine guns. These factors were all addressed in the British Official History, which does not directly apportion blame. ‘I heartily congratulate you on the work, I can find nothing to criticise,’ a grateful Pulteney enthused to the official historian after critiquing a draft copy.198 It was not much of an admission, but it was the closest Pulteney came to conceding that he had turned up for battle unprepared and been wholly outclassed by Soden and Hahn before Ovillers and La Boisselle.

Proof lay in the butcher’s bill. Pulteney’s III Corps racked up 11,501 casualties.199 This included 4407 killed, 6682 wounded, 380 missing and 32 prisoners. By contrast, Soden’s and Hahn’s regiments opposing 8th and 34th Divisions suffered at least a combined 1183 casualties, including 327 dead and 856 others wounded and missing.200 That equated to about one German casualty for every 9.7 British, a grim ratio by anyone’s maths.

Pulteney tried to gloss over the tragedy at the time by feting the 34th’s survivors with tributes.201 As Lieutenant-Colonel Somerset bitterly told it, four days after battle Pulteney ‘inspected the remnant of the 101st Brigade & complimented them on their bravery & tenacity.’202 Lieutenant-Colonel Shakespear continued:

He [Pulteney] specially referred to valuable service that they had performed in guarding the left flank of the 21st Division, which, had our small isolated detachments not held firmly on to the positions they had seized, might have been seriously endangered, and in fact the whole attack would have been in jeopardy, and all our line down to the French might have been rolled up.203

Pulteney was dealing exaggeration and lies. The 21st’s flank was not exposed to anything like the kind of danger Pulteney suggested, and XV and XIII Corps’ gains were never going to be rolled by a German counterattack from III Corps’ sector. Hahn and Soden did not have the resources for such a stroke, and never considered it.204 But in Pulteney’s mind pretty much anything could be dressed as its own opposite; his after-battle pep talk was all about hawking black as its own inverse and the outright defeat his corps had just suffered as nothing less than an aspect of victory.

Survivors knew the truth. In 8th KOYLI, for instance, just 25 of its 685 officers and men who went into battle turned up at the quartermaster’s depot afterwards. As Corporal Murray recalled, ‘The quartermaster was an acting captain, and he said “Is the battalion on the march back?” A lance corporal was in charge, and he said, “They’re here.”’205 The rest were dead, wounded, missing or stragglers yet to turn up. Walk over the fields and among the headstones at Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries around Ovillers and La Boisselle and the dead are still there, still mute witnesses to Pulteney’s incompetence.